Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European great powers and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the Carnatic Wars (1744–1763), and the Anglo-Spanish War (1762–1763). The opposing alliances were led by Great Britain and France, respectively, each seeking to establish global pre-eminence at the expense of the other.[6] Along with Spain, France fought Britain both in Europe and overseas with land-based armies and naval forces, while Britain's ally Prussia sought territorial expansion in Europe and consolidation of its power. Long-standing colonial rivalries pitted Britain against France and Spain in North America and the West Indies. They fought on a grand scale with consequential results. Prussia sought greater influence in the German states, while Austria wanted to regain Silesia, captured by Prussia in the previous war, and to contain Prussian influence.

In a realignment of traditional alliances, known as the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756, Prussia became part of a coalition led by Britain, which also included long-time Prussian competitor Hanover, at the time in personal union with Britain. At the same time, Austria ended centuries of conflict between the Bourbon and Habsburg families by allying with France, along with Saxony, Sweden, and Russia. Spain aligned formally with France in 1761, joining France in the Third Family Compact between the two Bourbon monarchies. Smaller German states either joined the Seven Years' War or supplied mercenaries to the parties involved in the conflict.

Anglo-French conflicts broke out in their North American colonies in 1754, when British and French colonial militias and their respective Native American allies engaged in small skirmishes, and later full-scale colonial warfare. The colonial conflicts would become a theatre of the Seven Years' War when war was officially declared two years later, and it effectively ended France's presence as a global hegemony. It has been called "the most important event to occur in eighteenth-century North America"[7] prior to the American Revolution. Spain entered the war on the French side in 1762, unsuccessfully attempting to invade Britain's ally Portugal in what became known as the Fantastic War. The alliance with France was a disaster for Spain, with the loss to Britain of two major ports, Havana in Cuba and Manila in the Philippines, which were returned in the 1763 Treaty of Paris between France, Spain and Great Britain. In Europe, the large-scale conflict that drew in most of the European powers was centred on the desire of Austria (long the political centre of the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation) to recover Silesia from Prussia. The Treaty of Hubertusburg ended the war between Saxony, Austria and Prussia, in 1763. Britain began its rise as the world's predominant colonial and naval power. France's supremacy in Europe was halted until after the French Revolution and the emergence of Napoleon Bonaparte. Prussia confirmed its status as a great power, challenging Austria for dominance within the German states, thus altering the European balance of power.

Summary

What came to be known as the Seven Years' War had roots in colonial America in conflicts between Great Britain and France in 1754, when the British sought to expand into territory claimed by the French in North America. The war came to be known as the French and Indian War, with both the British and the French and their respective Native American allies fighting for control of territory. Hostilities were heightened when a joint British and native Mingo force (led by a 22-year-old Lieutenant Colonel George Washington and Chief Tanacharison) ambushed a small French force at the Battle of Jumonville Glen on 28 May 1754. The conflict exploded across the colonial boundaries and extended to Britain's seizure of hundreds of French merchant ships at sea, with Horace Walpole describing his contemporary Washington's role therein as "the volley fired by a young Virginian in the backwoods of America [that] set the world on fire."[8]

Prussia, a rising power, struggled with Austria for dominance within and outside the Holy Roman Empire in central Europe. The Diplomatic Revolution of 1756 led to a massive realignment of the European alliance system: Austria allied itself with Russia and France in an attempt to regain the province of Silesia, which had been lost to Prussia in the earlier War of the Austrian Succession, while Prussia allied itself with Great Britain, who welcomed Prussia as an up-and-coming European land power who could help counterbalance France in Germany. Realizing that war was imminent, Prussia pre-emptively struck Saxony and quickly overran it. The result caused uproar across Europe. Reluctantly, by following the Imperial diet of the Holy Roman Empire, which declared war on Prussia on 17 January 1757, most of the states of the empire joined Austria's cause. The Anglo-Prussian alliance was joined by a few smaller German states within the empire (most notably the Electorate of Hanover but also Brunswick and Hesse-Kassel). Sweden, seeking to regain Pomerania (most of which had been lost to Prussia in previous wars), joined the coalition, seeing its chance when all the major continental powers of Europe opposed Prussia. Spain, bound by the Pacte de Famille, intervened on behalf of France and together they launched an unsuccessful invasion of Portugal in 1762. The Russian Empire was originally aligned with Austria, fearing Prussia's ambition on the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, but switched sides upon the succession of Tsar Peter III in 1762.

Many middle and small powers in Europe, as in the previous wars, tried steering away from the escalating conflict, even though they had interests in the conflict or with the belligerents. Denmark–Norway, for instance, was close to being dragged into the war on France's side when Peter III became Russian emperor and switched sides; Dano-Norwegian and Russian armies were close to ending up in battle, but the Russian emperor was deposed before war formally broke out. The Dutch Republic, a long-time British ally, kept its neutrality intact, not seeing why it should fight a costly war for British interests, and even tried to prevent Britain's domination in India. The taxation needed for war caused the Russian people considerable hardship, being added to the taxation of salt and alcohol begun by Empress Elizabeth in 1759 to complete her addition to the Winter Palace. Like Sweden, Russia concluded a separate peace with Prussia.

The war ended with two separate treaties dealing with the two different theaters of war. The Treaty of Paris between France, Spain and Great Britain ended the war in North America and for overseas territories taken in the conflict. The 1763 Treaty of Hubertusburg ended the war among Saxony, Austria and Prussia.

The war was successful for Great Britain, which gained the bulk of New France in North America, Spanish Florida, some individual Caribbean islands in the West Indies, the colony of Senegal on the West African coast, and superiority over the French trading outposts on the Indian subcontinent. The Native American tribes were excluded from the settlement; a subsequent conflict, known as Pontiac's War, which was a small-scale war between the indigenous tribe known as the Odawa and the British, where the Odawa claimed seven of the ten forts created or taken by the British to show them that they need to distribute land equally amongst their allies, was also unsuccessful in returning them to their pre-war status. In Europe, the war began disastrously for Prussia, but with a combination of good luck and successful strategy, King Frederick the Great managed to retrieve the Prussian position and retain the status quo ante bellum. Prussia solidified its position as a newer European great power. Although Austria failed to retrieve the territory of Silesia from Prussia (its original goal), its military prowess was also noted by the other powers. The involvement of Portugal and Sweden did not return them to their former status as great powers. France was deprived of many of its colonies and had saddled itself with heavy war debts that its inefficient financial system could barely handle. Spain lost Florida but gained French Louisiana and regained control of its colonies, e.g., Cuba and the Philippines, which had been captured by the British during the war.

Some historians have stated that the Seven Years' War was the first global war, taking place almost 160 years before World War I, known as the Great War before the outbreak of World War II, and globally influenced many later major events. Winston Churchill described the conflict as the "first world war". The war restructured not only the European political order, but also affected events all around the world, paving the way for the beginning of later British world supremacy in the 19th century, the rise of Prussia in Germany (eventually replacing Austria as the leading German state), the beginning of tensions in British North America, as well as a clear sign of France's revolutionary turmoil. It was characterized in Europe by sieges and the arson of towns as well as open battles with heavy losses.

Major battles

| Battle | Anglo-Prussian coalition numbers | Franco-Austrian coalition numbers | Anglo-Prussian coalition casualties | Franco-Austrian coalition casualties | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lobositz | 28,500 | 34,000 | 3,300 | 2,984 | Austrian victory |

| Prague | 64,000 | 61,000 | 14,300 | 13,600 | Prussian victory |

| Kolín | 34,000 | 54,000 | 13,733 | 8,100 | Austrian victory |

| Hastenbeck | 36,000 | 63,000 | 1,200 | 1,200 | French victory |

| Gross-Jägersdorf | 25,000 | 55,000 | 4,520 | 5,250 | Russian victory |

| Rossbach | 21,000 | 40,900 | 541 | 8,000 | Prussian victory |

| Breslau | 28,000 | 60,000 | 10,150 | 5,857 | Austrian victory |

| Leuthen | 36,000 | 65,000 | 6,259 | 22,000 | Prussian victory |

| Krefeld | 32,000 | 50,000 | 1,800 | 8,200 | Prussian-allied victory |

| Zorndorf | 36,000 | 44,000 | 11,390 | 21,529 | Indecisive |

| Belle Île | 9,000 | 3,000 | 810 | 3,000 | British victory |

| Saint Cast | 1,400 | 10,000 | 1,400 | 495 | French victory |

| Hochkirch | 39,000 | 78,000 | 9,097 | 7,590 | Austrian victory |

| Kay | 28,000 | 40,500 | 8,000 | 4,700 | Russian victory |

| Minden | 43,000 | 60,000 | 2,762 | 7,086 | British-allied victory |

| Kunersdorf | 49,000 | 98,000 | 18,503 | 15,741 | Russo-Austrian victory |

| Maxen | 15,000 | 32,000 | 15,000 | 934 | Austrian victory |

| Landeshut | 13,000 | 35,000 | 10,052 | 3,000 | Austrian victory |

| Warburg | 30,000 | 35,000 | 1,200 | 3,000 | British-allied victory |

| Liegnitz | 14,000 | 24,000 | 3,100 | 8,300 | Prussian victory |

| Kloster Kampen | 26,000 | 45,000 | 3,228 | 2,036 | French victory |

| Torgau | 48,500 | 52,000 | 17,120 | 11,260 | Prussian victory |

| Villinghausen | 60,000 | 100,000 | 1,600 | 5,000 | British-allied victory |

| Schweidnitz | 25,000 | 10,000 | 3,033 | 10,000 | Prussian victory |

| Wilhelmsthal | 40,000 | 70,000 | 700 | 4,500 | British-allied victory |

| Freiberg | 22,000 | 40,000 | 2,500 | 8,000 | Prussian victory |

| Battle | British-native numbers | French, Spanish and native numbers | British-native casualties | French, Spanish and native casualties | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monongahela | 1,300 | 891 | 906 | 96 | French-allied victory |

| Lake George | 1700 | 1500 | 331 | 339 | British-allied victory |

| Fort William Henry | 2,372 | 8,344 | 2,372 | Unknown | French-allied victory |

| Fort Ticonderoga I | 18,000 | 3,600 | 3,600 | 377 | French-allied victory |

| Louisbourg | 9,500 | 5,600 | 524 | 5,600 | British victory |

| Guadeloupe | 5,000 | 2,000 | 804 | 2,000 | British victory |

| Martinique | 8,000 | 8,200 | 500 | N/A | French victory |

| Fort Niagara | 3,200 | 1,786 | 100 | 486 | British-allied victory |

| Quebec I | 9,400 | 15,000 | 900 | N/A | British victory |

| Montmorency | 5,000 | 12,000 | 440 | 60 | French victory |

| Plains of Abraham | 4,828 | 4,500 | 664 | 644 | British-allied victory |

| Saint-Foy | 3,866 | 6,900 | 1,088 | 833 | French victory |

| Quebec II | 6,000 | 7,000 | 30 | 700 | British victory |

| Havana | 31,000 | 11,670 (Spanish) | 5,366 | 11,670 | British victory |

| Battle | British-sepoy numbers | Mughal-French numbers | British-sepoy casualties | Mughal-French casualties | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcutta I | 514 | 50,000 (Mughals) | 218 | 7,000 | Mughal victory |

| Calcutta II | 1,870 | 40,000 (Mughals) | 194 | 1,300 | British victory |

| Plassey | 2,884 | 50,000 (Mughals) | 63 | 500 | British victory |

| Chandannagar | 2,300 | 900 (French-sepoy) | 200 | 200 | British victory |

| Madras | 4,050 | 7,300 (French-sepoy) | 1,341 | 1,200 | British victory |

| Masulipatam | 7,246 | 2,600 (French-sepoy) | 286 | 1,500 | British victory |

| Wandiwash | 5,330 | 4,550 (French-sepoy) | 387 | 1,000 | British victory |

Nomenclature

In the historiography of some countries, the war is named after combatants in its respective theatres. In the present-day United States, the conflict is known as the French and Indian War (1754–1763). In English-speaking Canada—the balance of Britain's former North American colonies—it is called the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). In French-speaking Canada, it is known as La guerre de la Conquête (the War of the Conquest). Swedish historiography uses the name Pommerska kriget (the Pomeranian War), as the Sweden–Prussia conflict between 1757 and 1762 was limited to Pomerania in northern central Germany.[11] The Third Silesian War involved Prussia and Austria (1756–1763). On the Indian subcontinent, the conflict is called the Third Carnatic War (1757–1763).

The war was described by Winston Churchill[12] as the first "world war",[13] although this label was also given to various earlier conflicts like the Eighty Years' War, the Thirty Years' War, the War of the Spanish Succession, and the War of the Austrian Succession, as well as later conflicts like the Napoleonic Wars. Contemporaries sometimes informally refer to the war as "World War Zero". The term "Second Hundred Years' War" has been used in order to describe the almost continuous level of worldwide conflict between France and Great Britain during the entire 18th century, reminiscent of the Hundred Years' War of the 14th and 15th centuries.[14]

Background

In North America

The boundary between British and French possessions in North America was largely undefined in the 1750s. France had long claimed the entire Mississippi River basin. This was disputed by Britain. In the early 1750s the French began constructing a chain of forts in the Ohio River Valley to assert their claim and shield the Native American population from increasing British influence.

The British settlers along the coast were upset that French troops would now be close to the western borders of their colonies. They felt the French would encourage their tribal allies among the North American natives to attack them. Also, the British settlers wanted access to the fertile land of the Ohio River Valley for the new settlers that were flooding into the British colonies seeking farm land.[15]

The most important French fort planned was intended to occupy a position at "the Forks" where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet to form the Ohio River (present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Peaceful British attempts to halt this fort construction were unsuccessful, and the French proceeded to build the fort they named Fort Duquesne. British colonial militia from Virginia accompanied by Chief Tanacharison and a small number of Mingo warriors were sent to drive them out. Led by George Washington, they ambushed a small French force at Jumonville Glen on 28 May 1754 killing ten, including commander Joseph Coulon de Jumonville.[16] The French retaliated by attacking Washington's army at Fort Necessity on 3 July 1754 and forced Washington to surrender.[17] These were the first engagements of what would become the worldwide Seven Years' War.

Britain and France failed to negotiate a solution after receiving news about this in Europe. The two countries eventually sent regular troops to North America to enforce their claims. The first British action was the assault on Acadia on 16 June 1755 in the Battle of Fort Beauséjour,[18] which was immediately followed by their Expulsion of the Acadians.[19] In July, British Major General Edward Braddock led about 2,000 army troops and provincial militia on an expedition to retake Fort Duquesne, but the expedition ended in disastrous defeat.[20] In further action, Admiral Edward Boscawen fired on the French ship Alcide on 8 June 1755, capturing it and two troop ships. In September 1755, British colonial and French troops met in the inconclusive Battle of Lake George.[21]

The British also harassed French shipping beginning in August 1755, seizing hundreds of ships and capturing thousands of merchant seamen while the two nations were nominally at peace. Incensed, France prepared to attack Hanover, whose prince-elector was also the King of Great Britain and Menorca. Britain concluded a treaty whereby Prussia agreed to protect Hanover. In response France concluded an alliance with its long-time enemy Austria, an event known as the Diplomatic Revolution.

In Europe

In the War of the Austrian Succession,[22] which lasted from 1740 to 1748, King Frederick II, known as Frederick the Great, seized the prosperous province of Silesia from Austria. Empress Maria Theresa of Austria had signed the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748 in order to gain time to rebuild her military forces and forge new alliances.

The War of the Austrian Succession had seen the belligerents aligned on a time-honoured basis. France's traditional enemies, Great Britain and Austria, had coalesced just as they had done against Louis XIV. Prussia, the leading anti-Austrian state in Germany, had been supported by France. Neither group, however, found much reason to be satisfied with its partnership: British subsidies to Austria produced nothing of much help to the British, while the British military effort had not saved Silesia for Austria. Prussia, having secured Silesia, came to terms with Austria in disregard of French interests. Even so, France concluded a defensive alliance with Prussia in 1747, and the maintenance of the Anglo-Austrian alignment after 1748 was deemed essential by the Duke of Newcastle, British secretary of state in the ministry of his brother Henry Pelham. The collapse of that system and the aligning of France with Austria and of Great Britain with Prussia constituted what is known as the "Diplomatic Revolution" or the "reversal of alliances".

In 1756 Austria was making military preparations for war with Prussia and pursuing an alliance with Russia for this purpose. On 2 June 1756, Austria and Russia concluded a defensive alliance that covered their own territory and Poland against attack by Prussia or the Ottoman Empire. They also agreed to a secret clause that promised the restoration of Silesia and the countship of Glatz (now Kłodzko, Poland) to Austria in the event of hostilities with Prussia. Their real desire, however, was to destroy Frederick's power altogether, reducing his sway to his electorate of Brandenburg and giving East Prussia to Poland, an exchange that would be accompanied by the cession of the Polish Duchy of Courland to Russia. Alexey Bestuzhev-Ryumin, grand chancellor of Russia under Empress Elizabeth, was hostile to both France and Prussia, but he could not persuade Austrian statesman Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz to commit to offensive designs against Prussia so long as Prussia was able to rely on French support.

The Hanoverian King George II of Great Britain was passionately devoted to his family's continental holdings, but his commitments in Germany were counterbalanced by the demands of the British colonies overseas. If war against France for colonial expansion was to be resumed, then Hanover had to be secured against Franco-Prussian attack. France was very much interested in colonial expansion and was willing to exploit the vulnerability of Hanover in war against Great Britain, but it had no desire to divert forces to Central Europe for Prussia's interest.

French policy was, moreover, complicated by the existence of the Secret du Roi—a system of private diplomacy conducted by King Louis XV. Unbeknownst to his foreign minister, Louis had established a network of agents throughout Europe with the goal of pursuing personal political objectives that were often at odds with France's publicly stated policies. Louis's goals for le Secret du roi included the Polish crown for his kinsman Louis François de Bourbon, Prince of Conti, and the maintenance of Poland, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire as French allies in opposition to Russian and Austrian interests.

Frederick saw Saxony and Polish west Prussia as potential fields for expansion, but could not expect French support if he started an aggressive war for them. If he joined the French against the British in the hope of annexing Hanover, he might fall victim to an Austro-Russian attack. The hereditary elector of Saxony, Augustus III, was also elective King of Poland as Augustus III, but the two territories were physically separated by Brandenburg and Silesia. Neither state could pose as a great power. Saxony was merely a buffer between Prussia and Austrian Bohemia, whereas Poland, despite its union with the ancient lands of Lithuania, was prey to pro-French and pro-Russian factions. A Prussian scheme for compensating Frederick Augustus with Bohemia in exchange for Saxony obviously presupposed further spoliation of Austria.

In the attempt to satisfy Austria at the time, Britain gave their electoral vote in Hanover for the candidacy of Maria Theresa's son, Joseph II, as the Holy Roman Emperor, much to the dismay of Frederick and Prussia. Not only that, Britain would soon join the Austro-Russian alliance, but complications arose. Britain's basic framework for the alliance itself was to protect Hanover's interests against France. At the same time, Kaunitz kept approaching the French in the hope of establishing just such an alliance with Austria. Not only that, France had no intention to ally with Russia, who, years earlier, had meddled in France's affairs during Austria's succession war. France also saw the dismemberment of Prussia as threatening to the stability of Central Europe.

Years later, Kaunitz kept trying to establish France's alliance with Austria. He tried as hard as he could to avoid Austrian entanglement in Hanover's political affairs, and was even willing to trade Austrian Netherlands for France's aid in recapturing Silesia. Frustrated by this decision and by the Dutch Republic's insistence on neutrality, Britain soon turned to Russia. On 30 September 1755, Britain pledged financial aid to Russia in order to station 50,000 troops on the Livonian-Lithuanian border, so they could defend Britain's interests in Hanover immediately. Besthuzev, assuming the preparation was directed against Prussia, was more than happy to obey the request of the British. Unbeknownst to the other powers, King George II also made overtures to the Prussian king, Frederick, who, fearing the Austro-Russian intentions, was also desirous of a rapprochement with Britain. On 16 January 1756, the Convention of Westminster was signed, whereby Britain and Prussia promised to aid one another; the parties hoped to achieve lasting peace and stability in Europe.

The carefully coded word in the agreement proved no less catalytic for the other European powers. The results were absolute chaos. Empress Elizabeth of Russia was outraged at the duplicity of Britain's position. Not only that, but France was enraged and terrified, by the sudden betrayal of its only ally, Prussia. Austria, particularly Kaunitz, used this situation to their utmost advantage. Now-isolated France was forced to accede to the Austro-Russian alliance or face ruin. Thereafter, on 1 May 1756, the First Treaty of Versailles was signed, in which both nations pledged 24,000 troops to defend each other in the case of an attack. This diplomatic revolution proved to be an important cause of the war; although both treaties were ostensibly defensive in nature, the actions of both coalitions made the war virtually inevitable.

Methods and technologies

European warfare in the early modern period was characterised by the widespread adoption of firearms in combination with more traditional bladed weapons. Eighteenth-century European armies were built around units of massed infantry armed with smoothbore flintlock muskets and bayonets. Cavalrymen were equipped with sabres and pistols or carbines; light cavalry were used principally for reconnaissance, screening and tactical communications, while heavy cavalry were used as tactical reserves and deployed for shock attacks. Smoothbore artillery provided fire support and played the leading role in siege warfare.[23] Strategic warfare in this period centred around control of key fortifications positioned so as to command the surrounding regions and roads, with lengthy sieges a common feature of armed conflict. Decisive field battles were relatively rare.[24]

The Seven Years' War, like most European wars of the eighteenth century, was fought as a so-called cabinet war in which disciplined regular armies were equipped and supplied by the state to conduct warfare on behalf of the sovereign's interests. Occupied enemy territories were regularly taxed and extorted for funds, but large-scale atrocities against civilian populations were rare compared with conflicts in the previous century.[25] Military logistics was the decisive factor in many wars, as armies had grown too large to support themselves on prolonged campaigns by foraging and plunder alone. Military supplies were stored in centralised magazines and distributed by baggage trains that were highly vulnerable to enemy raids.[26] Armies were generally unable to sustain combat operations during winter and normally established winter quarters in the cold season, resuming their campaigns with the return of spring.[23]

Strategies

For much of the eighteenth century, France approached its wars in the same way. It would let colonies defend themselves or would offer only minimal help (sending them limited numbers of troops or inexperienced soldiers), anticipating that fights for the colonies would most likely be lost anyway.[27] This strategy was to a degree forced upon France: geography, coupled with the superiority of the British navy, made it difficult for the French navy to provide significant supplies and support to overseas colonies.[28] Similarly, several long land borders made an effective domestic army imperative for any French ruler.[29] Given these military necessities, the French government, unsurprisingly, based its strategy overwhelmingly on the army in Europe: it would keep most of its army on the continent, hoping for victories closer to home.[29] The plan was to fight to the end of hostilities and then, in treaty negotiations, to trade territorial acquisitions in Europe to regain lost overseas possessions (as had happened in, e.g., the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle). This approach did not serve France well in the war, as the colonies were indeed lost, and although much of the European war went well, by its end France had few counterbalancing European successes.[30]

The British—by inclination as well as for practical reasons—had tended to avoid large-scale commitments of troops on the continent.[31] They sought to offset the disadvantage of this in Europe by allying themselves with one or more continental powers whose interests were antithetical to those of their enemies, particularly France.[32] By subsidising the armies of continental allies, Britain could turn London's enormous financial power to military advantage. In the Seven Years' War, the British chose as their principal partner the most brilliant general of the day, Frederick the Great of Prussia, then the rising power in central Europe, and paid Frederick substantial subsidies for his campaigns.[33] This was accomplished in the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756, in which Britain ended its long-standing alliance with Austria in favour of Prussia, leaving Austria to side with France. In marked contrast to France, Britain strove to prosecute the war actively overseas, taking full advantage of its naval power.[34][35] The British pursued a dual strategy—naval blockade and bombardment of enemy ports, and rapid movement of troops by sea.[36] They harassed enemy shipping and attacked enemy colonies, frequently using colonists from nearby British colonies in the effort.

The Russians and the Austrians were determined to reduce the power of Prussia, the new threat on their doorstep, and Austria was anxious to regain Silesia, lost to Prussia in the War of the Austrian Succession. Along with France, Russia and Austria agreed in 1756 to mutual defence and an attack by Austria and Russia on Prussia, subsidized by France.[37]

Europe

William Pitt the Elder, who entered the cabinet in 1756, had a grand vision for the war that made it entirely different from previous wars with France. As prime minister, Pitt committed Britain to a grand strategy of seizing the entire French Empire, especially its possessions in North America and India. Britain's main weapon was the Royal Navy, which could control the seas and bring as many invasion troops as were needed. He also planned to use colonial forces from the thirteen American colonies, working under the command of British regulars, to invade New France. In order to tie the French army down he subsidized his European allies. Pitt was head of the government from 1756 to 1761, and even after that the British continued his strategy. It proved completely successful.[38] Pitt had a clear appreciation of the enormous value of imperial possessions, and realized the vulnerability of the French Empire.[39]

1756

The British prime minister, the Duke of Newcastle, was optimistic that the new series of alliances could prevent war from breaking out in Europe.[40] However, a large French force was assembled at Toulon, and the French opened the campaign against the British with an attack on Minorca in the Mediterranean. A British attempt at relief was foiled at the Battle of Minorca, and the island was captured on 28 June (for which Admiral Byng was court-martialed and executed).[41] Britain formally declared war on France on 17 May,[42] nearly two years after fighting had broken out in the Ohio Country.

Frederick II of Prussia had received reports of the clashes in North America and had formed an alliance with Great Britain. On 29 August 1756, he led Prussian troops across the border of Saxony, one of the small German states in league with Austria. He intended this as a bold pre-emption of an anticipated Austro-French invasion of Silesia. He had three goals in his new war on Austria. First, he would seize Saxony and eliminate it as a threat to Prussia, then use the Saxon army and treasury to aid the Prussian war effort. His second goal was to advance into Bohemia, where he might set up winter quarters at Austria's expense. Thirdly, he wanted to invade Moravia from Silesia, seize the fortress at Olmütz, and advance on Vienna to force an end to the war.[43]

Accordingly, leaving Field Marshal Count Kurt von Schwerin in Silesia with 25,000 soldiers to guard against incursions from Moravia and Hungary, and leaving Field Marshal Hans von Lehwaldt in East Prussia to guard against Russian invasion from the east, Frederick set off with his army for Saxony. The Prussian army marched in three columns. On the right was a column of about 15,000 men under the command of Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick. On the left was a column of 18,000 men under the command of the Duke of Brunswick-Bevern. In the centre was Frederick II, himself with Field Marshal James Keith commanding a corps of 30,000 troops.[43] Ferdinand of Brunswick was to close in on the town of Chemnitz. The Duke of Brunswick-Bevern was to traverse Lusatia to close in on Bautzen. Meanwhile, Frederick and Keith would make for Dresden.

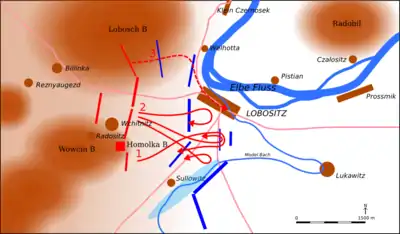

The Saxon and Austrian armies were unprepared, and their forces were scattered. Frederick occupied Dresden with little or no opposition from the Saxons.[44] At the Battle of Lobositz on 1 October 1756, Frederick stumbled into one of the embarrassments of his career. Severely underestimating a reformed Austrian army under General Maximilian Ulysses Browne, he found himself outmanoeuvred and outgunned, and at one point in the confusion even ordered his troops to fire on retreating Prussian cavalry. Frederick actually fled the field of battle, leaving Field Marshall Keith in command. Browne, however, also left the field, in a vain attempt to meet up with an isolated Saxon army holed up in the fortress at Pirna. As the Prussians technically remained in control of the field of battle, Frederick, in a masterful coverup, claimed Lobositz as a Prussian victory.[45] The Prussians then occupied Saxony; after the siege of Pirna, the Saxon army surrendered in October 1756, and was forcibly incorporated into the Prussian army. The attack on neutral Saxony caused outrage across Europe and led to the strengthening of the anti-Prussian coalition.[46] The Austrians had succeeded in partially occupying Silesia and, more importantly, denying Frederick winter quarters in Bohemia. Frederick had proven to be overly confident to the point of arrogance and his errors were very costly for Prussia's smaller army. This led him to remark that he did not fight the same Austrians as he had during the previous war.[47]

Britain had been surprised by the sudden Prussian offensive but now began shipping supplies and £670,000 (equivalent to £106 million in 2022) to its new ally.[48] A combined force of allied German states was organised by the British to protect Hanover from French invasion, under the command of the Duke of Cumberland.[49] The British attempted to persuade the Dutch Republic to join the alliance, but the request was rejected, as the Dutch wished to remain fully neutral.[50] Despite the huge disparity in numbers, the year had been successful for the Prussian-led forces on the continent, in contrast to the British campaigns in North America.

1757

On 18 April 1757, Frederick II again took the initiative by marching into the Kingdom of Bohemia, hoping to inflict a decisive defeat on Austrian forces.[51] After winning the bloody Battle of Prague on 6 May 1757, in which both forces suffered major casualties, the Prussians forced the Austrians back into the fortifications of Prague. The Prussian army then laid siege to the city.[52] In response, Austrian commander Leopold von Daun collected a force of 30,000 men to come to the relief of Prague.[53] Following the battle at Prague, Frederick took 5,000 troops from the siege at Prague and sent them to reinforce the 19,000-man army under the Duke of Brunswick-Bevern at Kolín in Bohemia.[54] Daun arrived too late to participate in the battle of Prague, but picked up 16,000 men who had escaped from the battle. With this army he slowly moved to relieve Prague. The Prussian army was too weak to simultaneously besiege Prague and keep Daun away, and Frederick was forced to attack prepared positions. The resulting Battle of Kolín was a sharp defeat for Frederick, his first. His losses further forced him to lift the siege and withdraw from Bohemia altogether.[52]

Later that summer, the Russians under Field Marshal Apraksin besieged Memel with 75,000 troops. Memel had one of the strongest fortresses in Prussia. However, after five days of artillery bombardment, the Russian army was able to storm it.[55] The Russians then used Memel as a base to invade East Prussia and defeated a smaller Prussian force in the fiercely contested Battle of Gross-Jägersdorf on 30 August 1757. In the words of the American historian Daniel Marston, Gross-Jägersdorf left the Prussians with "a newfound respect for the fighting capabilities of the Russians that was reinforced in the later battles of Zorndorf and Kunersdorf".[56] However, the Russians were not yet able to take Königsberg after using up their supplies of cannonballs at Memel, and Gross-Jägersdorf retreated soon afterwards.

Logistics was a recurring problem for the Russians throughout the war.[57] The Russians lacked a quartermaster's department capable of keeping armies operating in Central Europe properly supplied over the primitive mud roads of eastern Europe.[57] The tendency of Russian armies to break off operations after fighting a major battle, even when they were not defeated, was less about their casualties and more about their supply lines; after expending much of their munitions in a battle, Russian generals did not wish to risk another battle knowing resupply would be a long time coming.[57] This long-standing weakness was evident in the Russian-Ottoman War of 1735–1739, where Russian battle victories led to only modest war gains due to problems supplying their armies.[58] The Russian quartermasters department had not improved, so the same problems reoccurred in Prussia.[58] Still, the Imperial Russian Army was a new threat to Prussia. Not only was Frederick forced to break off his invasion of Bohemia, he was now forced to withdraw further into Prussian-controlled territory.[59] His defeats on the battlefield brought still more opportunistic nations into the war. Sweden declared war on Prussia and invaded Pomerania with 17,000 men.[55] Sweden felt this small army was all that was needed to occupy Pomerania and felt the Swedish army would not need to engage with the Prussians because the Prussians were occupied on so many other fronts.

This problem was compounded when the main Hanoverian army under Cumberland, which include Hesse-Kassel and Brunswick troops, was defeated at the Battle of Hastenbeck and forced to surrender entirely at the Convention of Klosterzeven following a French Invasion of Hanover.[60] The convention removed Hanover from the war, leaving the western approach to Prussian territory extremely vulnerable. Frederick sent urgent requests to Britain for more substantial assistance, as he was now without any outside military support for his forces in Germany.[61]

Things were looking grim for Prussia now, with the Austrians mobilising to attack Prussian-controlled soil and a combined French and Reichsarmee force under Prince Soubise approaching from the west. The Reichsarmee was a collection of armies from the smaller German states that had banded together to heed the appeal of the Holy Roman Emperor Franz I of Austria against Frederick.[62] However, in November and December 1757, the whole situation in Germany was reversed. First, Frederick devastated Soubise's forces at the Battle of Rossbach on 5 November 1757[63] and then routed a vastly superior Austrian force at the Battle of Leuthen on 5 December 1757.[64] Rossbach was the only battle between the French and the Prussians during the entire war.[62] At Rossbach, the Prussians lost about 548 men killed while the Franco-Reichsarmee force under Soubise lost about 10,000 killed.[65] Frederick always called Leuthen his greatest victory, an assessment shared by many at the time as the Austrian Army was considered to be a highly professional force.[65] With these victories, Frederick once again established himself as Europe's premier general and his men as Europe's most accomplished soldiers. However, Frederick missed an opportunity to completely destroy the Austrian army at Leuthen; although depleted, it escaped back into Bohemia. He hoped the two smashing victories would bring Maria Theresa to the peace table, but she was determined not to negotiate until she had re-taken Silesia. Maria Theresa also improved the Austrians' command after Leuthen by replacing her incompetent brother-in-law, Charles of Lorraine, with Daun, who was now a field marshal.

Calculating that no further Russian advance was likely until 1758, Frederick moved the bulk of his eastern forces to Pomerania under the command of Marshal Lehwaldt, where they were to repel the Swedish invasion. In short order, the Prussian army drove the Swedes back, occupied most of Swedish Pomerania, and blockaded its capital Stralsund.[66] George II of Great Britain, on the advice of his British ministers after the battle of Rossbach, revoked the Convention of Klosterzeven, and Hanover reentered the war.[67] Over the winter the new commander of the Hanoverian forces, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick (until immediately before a commander in the Prussian Army), regrouped his army and launched a series of offensives that drove the French back across the River Rhine. Ferdinand's forces kept Prussia's western flank secure for the rest of the war.[68] The British had suffered further defeats in North America, particularly at Fort William Henry. At home, however, stability had been established. Since 1756, successive governments led by Newcastle and Pitt had fallen. In August 1757, the two men agreed to a political partnership and formed a coalition government that gave new, firmer direction to the war effort. The new strategy emphasised both Newcastle's commitment to British involvement on the continent, particularly in defence of its German possessions, and Pitt's determination to use naval power to seize French colonies around the globe. This "dual strategy" would dominate British policy for the next five years.

Between 10 and 17 October 1757, a Hungarian general, Count András Hadik, serving in the Austrian army, executed what may be the most famous hussar action in history. When the Prussian king, Frederick, was marching south with his powerful armies, the Hungarian general unexpectedly swung his force of 5,000, mostly hussars, around the Prussians and occupied part of their capital, Berlin, for one night.[69] The city was spared for a negotiated ransom of 200,000 thalers.[69] When Frederick heard about this humiliating occupation, he immediately sent a larger force to free the city. Hadik, however, left the city with his hussars and safely reached the Austrian lines. Subsequently, Hadik was promoted to the rank of marshal in the Austrian Army.

1758

In early 1758, Frederick launched an invasion of Moravia and laid siege to Olmütz (now Olomouc, Czech Republic).[70] Following an Austrian victory at the Battle of Domstadtl that wiped out a supply convoy destined for Olmütz, Frederick broke off the siege and withdrew from Moravia. It marked the end of his final attempt to launch a major invasion of Austrian territory.[71] In January 1758, the Russians invaded East Prussia, where the province, almost denuded of troops, put up little opposition.[62] East Prussia had been occupied by Russian forces over the winter and would remain under their control until 1762, although it was far less strategically valuable to Prussia than Brandenburg or Silesia. In any case, Frederick did not see the Russians as an immediate threat and instead entertained hopes of first fighting a decisive battle against Austria that would knock them out of the war.

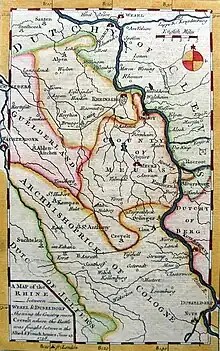

In April 1758, the British concluded the Anglo-Prussian Convention with Frederick in which they committed to pay him an annual subsidy of £670,000. Britain also dispatched 9,000 troops to reinforce Ferdinand's Hanoverian army, the first British troop commitment on the continent and a reversal in the policy of Pitt. Ferdinand's Hanoverian army, supplemented by some Prussian troops, had succeeded in driving the French from Hanover and Westphalia and re-captured the port of Emden in March 1758 before crossing the Rhine with his own forces, which caused alarm in France. Despite Ferdinand's victory over the French at the Battle of Krefeld and the brief occupation of Düsseldorf, he was compelled by the successful manoeuvering of larger French forces to withdraw across the Rhine.[72]

By this point Frederick was increasingly concerned by the Russian advance from the east and marched to counter it. Just east of the Oder in Brandenburg-Neumark, at the Battle of Zorndorf (now Sarbinowo, Poland), a Prussian army of 35,000 men under Frederick on 25 August 1758, fought a Russian army of 43,000 commanded by Count William Fermor.[73] Both sides suffered heavy casualties—the Prussians 12,800, the Russians 18,000—but the Russians withdrew, and Frederick claimed victory.[74] The American historian Daniel Marston described Zorndorf as a "draw" as both sides were too exhausted and had taken such losses that neither wished to fight another battle with the other.[75] In the undecided Battle of Tornow on 25 September, a Swedish army repulsed six assaults by a Prussian army but did not push on Berlin following the Battle of Fehrbellin.[76]

The war was continuing indecisively when on 14 October Marshal Daun's Austrians surprised the main Prussian army at the Battle of Hochkirch in Saxony.[77] Frederick lost much of his artillery but retreated in good order, helped by dense woods. The Austrians had ultimately made little progress in the campaign in Saxony despite Hochkirch and had failed to achieve a decisive breakthrough. After a thwarted attempt to take Dresden, Daun's troops were forced to withdraw to Austrian territory for the winter, so that Saxony remained under Prussian occupation.[78] At the same time, the Russians failed in an attempt to take Kolberg in Pomerania (now Kołobrzeg, Poland) from the Prussians.[79]

In France, 1758 had been disappointing, and in the wake of this a new chief minister, the Duc de Choiseul, was appointed. Choiseul planned to end the war in 1759 by making strong attacks on Britain and Hanover.

1759–1760

Prussia suffered several defeats in 1759. At the Battle of Kay, or Paltzig, the Russian Count Saltykov with 40,000 Russians defeated 26,000 Prussians commanded by General Carl Heinrich von Wedel. Though the Hanoverians defeated an army of 60,000 French at Minden, Austrian general Daun forced the surrender of an entire Prussian corps of 13,000 in the Battle of Maxen. Frederick himself lost half his army in the Battle of Kunersdorf (now Kunowice, Poland), the worst defeat in his military career and one that drove him to the brink of abdication and thoughts of suicide. The disaster resulted partly from his misjudgment of the Russians, who had already demonstrated their strength at Zorndorf and at Gross-Jägersdorf (now Motornoye, Russia), and partly from good cooperation between the Russian and Austrian forces. However, disagreements with the Austrians over logistics and supplies resulted in the Russians withdrawing east yet again after Kunersdorf, ultimately enabling Frederick to re-group his shattered forces.

The French planned to invade the British Isles during 1759 by accumulating troops near the mouth of the Loire and concentrating their Brest and Toulon fleets. However, two sea defeats prevented this. In August, the Mediterranean fleet under Jean-François de La Clue-Sabran was scattered by a larger British fleet under Edward Boscawen at the Battle of Lagos. In the Battle of Quiberon Bay on 20 November, the British admiral Edward Hawke with 23 ships of the line caught the French Brest fleet with 21 ships of the line under Marshal de Conflans and sank, captured, or forced many of them aground, putting an end to the French plans.

The year 1760 brought yet more Prussian disasters. The general Fouqué was defeated by the Austrians in the Battle of Landeshut. The French captured Marburg in Hesse and the Swedes part of Pomerania. The Hanoverians were victorious over the French at the Battle of Warburg, their continued success preventing France from sending troops to aid the Austrians against Prussia in the east.

Despite this, the Austrians, under the command of General Laudon, captured Glatz (now Kłodzko, Poland) in Silesia. In the Battle of Liegnitz Frederick scored a strong victory despite being outnumbered three to one. The Russians under General Saltykov and Austrians under General Lacy briefly occupied his capital, Berlin, in October, but could not hold it for long. Still, the loss of Berlin to the Russians and Austrians was a great blow to Frederick's prestige as many pointed out that the Prussians had no hope of occupying temporarily or otherwise St. Petersburg or Vienna. In November 1760, Frederick was once more victorious, defeating the able Daun in the Battle of Torgau, but he suffered very heavy casualties, and the Austrians retreated in good order.

Meanwhile, after the battle of Kunersdorf, the Russian army was mostly inactive due mostly to their tenuous supply lines.[80] Russian logistics were so poor that in October 1759, an agreement was signed under which the Austrians undertook to supply the Russians as the quartermaster's department of the Russian Army was badly strained by the demands of Russian armies operating so far from home.[57] As it was, the requirement that the Austrian quartermaster's department supply both the Austrian and Russian armies proved beyond its capacity, and in practice, the Russians received little in the way of supplies from the Austrians.[57] At Liegnitz (now Legnica, Poland), the Russians arrived too late to participate in the battle. They made two attempts to storm the fortress of Kolberg, but neither succeeded. The tenacious resistance of Kolberg allowed Frederick to focus on the Austrians instead of having to split his forces.

1761–1762

Prussia began the 1761 campaign with just 100,000 available troops, many of them new recruits, and its situation seemed desperate.[81] However, the Austrian and Russian forces were also heavily depleted and could not launch a major offensive.

In February 1761, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick surprised French troops at Langensalza and then advanced to besiege Cassel in March. He was forced to lift the siege and retreat after French forces regrouped and captured several thousand of his men at the Battle of Grünberg. At the Battle of Villinghausen, forces under Ferdinand defeated a 92,000-man French army.

On the eastern front, progress was very slow. The Russian Army was heavily dependent upon its main magazines in Poland, and the Prussian Army launched several successful raids against them. One of them, led by general Platen in September resulted in the loss of 2,000 Russians, mostly captured, and the destruction of 5,000 wagons.[82] Deprived of men, the Prussians had to resort to this new sort of warfare, raiding, to delay the advance of their enemies. Frederick's army, though depleted, was left unmolested at its headquarters in Brunzelwitz, as both the Austrians and the Russians were hesitant to attack it. Nonetheless, at the end of 1761, Prussia suffered two critical setbacks. The Russians under Zakhar Chernyshev and Pyotr Rumyantsev stormed Kolberg in Pomerania, while the Austrians captured Schweidnitz. The loss of Kolberg cost Prussia its last port on the Baltic Sea.[83] A major problem for the Russians throughout the war had always been their weak logistics, which prevented their generals from following up their victories, and now with the fall of Kolberg, the Russians could at long last supply their armies in Central Europe via the sea.[84] The fact that the Russians could now supply their armies over the sea, which was considerably faster and safer (Prussian cavalry could not intercept Russian ships in the Baltic) than over the land threatened to swing the balance of power decisively against Prussia, as Frederick could not spare any troops to protect his capital.[84] In Britain, it was speculated that a total Prussian collapse was now imminent.

Britain now threatened to withdraw its subsidies if Frederick did not consider offering concessions to secure peace. As the Prussian armies had dwindled to just 60,000 men and with Berlin itself about to come under siege, the survival of both Prussia and its king was severely threatened. Then on 5 January 1762 the Russian Empress Elizabeth died. Her Prussophile successor, Peter III, at once ended the Russian occupation of East Prussia and Pomerania (see: the Treaty of Saint Petersburg) and mediated Frederick's truce with Sweden. He also placed a corps of his own troops under Frederick's command. Frederick was then able to muster a larger army, of 120,000 men, and concentrate it against Austria.[82] He drove them from much of Silesia after recapturing Schweidnitz, while his brother Henry won a victory in Saxony in the Battle of Freiberg (29 October 1762). At the same time, his Brunswick allies captured the key town of Göttingen and compounded this by taking Cassel.

Two new countries entered the war in 1762. Britain declared war against Spain on 4 January 1762; Spain reacted by issuing its own declaration of war against Britain on 18 January.[85] Portugal followed by joining the war on Britain's side. Spain, aided by the French, launched an invasion of Portugal and succeeded in capturing Almeida. The arrival of British reinforcements stalled a further Spanish advance, and in the Battle of Valencia de Alcántara British-Portuguese forces overran a major Spanish supply base. The invaders were stopped on the heights in front of Abrantes (called the pass to Lisbon) where the Anglo-Portuguese were entrenched. Eventually the Anglo-Portuguese army, aided by guerrillas and practising a scorched earth strategy,[86][87][88] chased the greatly reduced Franco-Spanish army back to Spain,[89][90][91] recovering almost all the lost towns, among them the Spanish headquarters in Castelo Branco full of wounded and sick that had been left behind.[92]

Meanwhile, the long British naval blockade of French ports had sapped the morale of the French populace. Morale declined further when news of defeat in the Battle of Signal Hill in Newfoundland reached Paris.[93] After Russia's about-face, Sweden's withdrawal and Prussia's two victories against Austria, Louis XV became convinced that Austria would be unable to re-conquer Silesia (the condition for which France would receive the Austrian Netherlands) without financial and material subsidies, which Louis was no longer willing to provide. He therefore made peace with Frederick and evacuated Prussia's Rhineland territories, ending France's involvement in the war in Germany.[94]

1763

By 1763, the war in central Europe was essentially a stalemate between Prussia and Austria. Prussia had retaken nearly all of Silesia from the Austrians after Frederick's narrow victory over Daun at the Battle of Burkersdorf. After his brother Henry's 1762 victory at the Battle of Freiberg, Frederick held most of Saxony but not its capital, Dresden. His financial situation was not dire, but his kingdom was devastated and his army severely weakened. His manpower had dramatically decreased, and he had lost so many effective officers and generals that an offensive against Dresden seemed impossible.[47] British subsidies had been stopped by the new prime minister, John Stuart (Lord Bute), and the Russian emperor had been overthrown by his wife, Catherine, who ended Russia's alliance with Prussia and withdrew from the war. Austria, however, like most participants, was facing a severe financial crisis and had to decrease the size of its army, which greatly affected its offensive power.[47] Indeed, after having effectively sustained a long war, its administration was in disarray.[95] By that time, it still held Dresden, the southeastern parts of Saxony, and the county of Glatz in southern Silesia, but the prospect of victory was dim without Russian support, and Maria Theresa had largely given up her hopes of re-conquering Silesia; her Chancellor, husband and eldest son were all urging her to make peace, while Daun was hesitant to attack Frederick. In 1763 a peace settlement was reached at the Treaty of Hubertusburg, in which Glatz was returned to Prussia in exchange for the Prussian evacuation of Saxony. This ended the war in central Europe.

The stalemate had really been reached by 1759–1760, and Prussia and Austria were nearly out of money. The materials of both sides had been largely consumed. Frederick was no longer receiving subsidies from Britain; the Golden Cavalry of St. George had produced nearly 13 million dollars (equivalent). He had melted and coined most of the church silver, had ransacked the palaces of his kingdom and coined that silver, and reduced his purchasing power by mixing it with copper. His banks' capital was exhausted, and he had pawned nearly everything of value from his own estate. While Frederick still had a significant amount of money left from the prior British subsidies, he hoped to use it to restore his kingdom's prosperity in peacetime; in any case, Prussia's population was so depleted that he could not sustain another long campaign.[96] Similarly, Maria Theresa had reached the limit of her resources. She had pawned her jewels in 1758; in 1760, she approved a public subscription for support and urged her public to bring their silver to the mint. French subsidies were no longer provided.[96] Although she had many young men still to draft, she could not conscript them and did not dare to resort to impressment, as Frederick had done.[97] She had even dismissed some men because it was too expensive to feed them.[96]

British amphibious "descents"

Great Britain planned a "descent" (an amphibious demonstration or raid) on Rochefort, a joint operation to overrun the town and burn shipping in the Charente. The expedition set out on 8 September 1757, Sir John Mordaunt commanding the troops and Sir Edward Hawke the fleet. On 23 September, the Isle d'Aix was taken, but military staff dithered and lost so much time that Rochefort became unassailable.[98] The expedition abandoned the Isle d'Aix, returning to Great Britain on 1 October.

Despite the debatable strategic success and the operational failure of the descent on Rochefort, William Pitt—who saw purpose in this type of asymmetric enterprise—prepared to continue such operations.[98] An army was assembled under the command of Charles Spencer; he was aided by George Germain. The naval squadron and transports for the expedition were commanded by Richard Howe. The army landed on 5 June 1758 at Cancalle Bay, proceeded to St. Malo, and, finding that it would take prolonged siege to capture it, instead attacked the nearby port of St. Servan. It burned shipping in the harbour, roughly 80 French privateers and merchantmen, as well as four warships which were under construction.[99] The force then re-embarked under threat of the arrival of French relief forces. An attack on Havre de Grace was called off, and the fleet sailed on to Cherbourg; the weather being bad and provisions low, that too was abandoned, and the expedition returned having damaged French privateering and provided further strategic demonstration against the French coast.

Pitt now prepared to send troops into Germany; and both Marlborough and Sackville, disgusted by what they perceived as the futility of the "descents", obtained commissions in that army. The elderly General Bligh was appointed to command a new "descent", escorted by Howe. The campaign began propitiously with the Raid on Cherbourg. Covered by naval bombardment, the army drove off the French force detailed to oppose their landing, captured Cherbourg, and destroyed its fortifications, docks and shipping.

The troops were reembarked and moved to the Bay of St. Lunaire in Brittany where, on 3 September, they were landed to operate against St. Malo; however, this action proved impractical. Worsening weather forced the two armies to separate: the ships sailed for the safer anchorage of St. Cast, while the army proceeded overland. The tardiness of Bligh in moving his forces allowed a French force of 10,000 from Brest to catch up with him and open fire on the reembarkation troops. At the Battle of Saint Cast a rear-guard of 1,400 under Dury held off the French while the rest of the army embarked. They could not be saved; 750, including Dury, were killed and the rest captured.

Other continents

The colonial conflict mainly between France and Britain took place in India, North America, Europe, the West Indies, the Philippines, and coastal Africa. Over the course of the war, Great Britain gained enormous areas of land and influence at the expense of the French and the Spanish Empires.

Great Britain lost Menorca in the Mediterranean to the French in 1756 but captured Fort Saint Louis, the centre of the French colonies in Senegal, in 1758. More importantly, the British defeated the French in its defence of New France in 1759, with the fall of Quebec. The buffer that French North America had provided to New Spain, the Spanish Empire's most important overseas holding, was now lost. Spain had entered the war after the Third Family Compact (15 August 1761) with France.[100] The British Royal Navy took the French Caribbean sugar colonies of Guadeloupe in 1759 and Martinique in 1762 as well as the Spanish Empire's main port in the West Indies, Havana in Cuba, and its main Asian port of Manila in the Philippines, both major Spanish colonial cities. British attempts at expansion into the hinterlands of Cuba and the Philippines met with stiff resistance. In the Philippines, the British were confined to Manila until their agreed upon withdrawal at the war's end.

North America

During the war, the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy were allied with the British. Native Americans of the Laurentian valley—the Algonquin, the Abenaki, the Huron and others—were allied with the French. Although the Algonquin tribes living north of the Great Lakes and along the St. Lawrence River were not directly concerned with the fate of the Ohio River Valley tribes, they had been victims of the Iroquois Confederation which included the Seneca, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Tuscarora tribes of central New York. The Iroquois had encroached on Algonquin territory and pushed the Algonquins west beyond Lake Michigan and to the shore of the St. Lawrence.[101] The Algonquin tribes were interested in fighting against the Iroquois. Throughout New England, New York and the north-west, Native American tribes formed differing alliances with the major belligerents.

In 1756 and 1757, the French captured Fort Oswego[102] and Fort William Henry from the British.[103] The latter victory was marred when France's native allies broke the terms of capitulation and attacked the retreating British column, which was under French guard, slaughtering and scalping soldiers and taking captive many men, women and children while the French refused to protect their captives.[104] French naval deployments in 1757 also successfully defended the key Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island called Ile du Roi by the French, securing the seaward approaches to Quebec.[105]

British Prime Minister William Pitt's focus on the colonies for the 1758 campaign paid off with the taking of Louisbourg after French reinforcements were blocked by British naval victory in the Battle of Cartagena and in the successful capture of Fort Duquesne[106] and Fort Frontenac.[107] The British also continued the process of deporting the Acadian population with a wave of major operations against Île Saint-Jean (present-day Prince Edward Island), and the St. John River and the Petitcodiac River Valleys. The celebration of these successes was dampened by their embarrassing defeat in the Battle of Carillon (Ticonderoga), in which 4,000 French troops repulsed 16,000 British. When the British led by generals James Abercrombie and George Howe attacked, they believed that the French led by Lieutenant General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm were defended only by a small abatis which could be taken easily given the British force's significant numerical advantage. The British offensive which was supposed to advance in tight columns and overwhelm the French defenders fell into confusion and scattered, leaving large spaces in their ranks. When François Gaston de Lévis sent 1,000 soldiers to reinforce Montcalm's struggling troops, the British were pinned down in the brush by intense French musket fire and they were forced to retreat.

All of Britain's campaigns against New France succeeded in 1759, part of what became known as an Annus Mirabilis. Starting in June 1759, the British under James Wolfe and James Murray set up camp on the Ile d'Orleans across the St. Lawrence River from Quebec, enabling them to commence the 3-month siege that ensued. The French under the Marquis de Montcalm anticipated a British assault to the east of Quebec so he ordered his soldiers to fortify the region of Beauport. In July 1759, Fort Niagara[108] and Fort Carillon[109] fell to sizable British forces, cutting off French frontier forts further west. On 31 July, the British attacked with 4,000 soldiers but the French positioned high up on the cliffs overlooking the Montmorency Falls forced the British forces to withdraw to the Ile d'Orleans. While Wolfe and Murray planned a second offensive, British rangers raided French settlements along the St. Lawrence, destroying food supplies, ammunition and other goods in an attempt to vanquish the French through starvation.

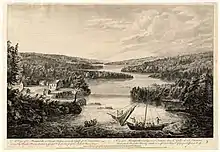

On 13 September 1759, General James Wolfe led 5,000 troops up a goat path to the Plains of Abraham, 1 mile west of Quebec City. He had positioned his army between Montcalm's forces an hour's march to the east and Louis Antoine de Bougainville's regiments to the west, which could be mobilised within 3 hours. Instead of waiting for a coordinated attack with Bougainville, Montcalm attacked immediately. When his 3,500 troops advanced, their lines became scattered in a disorderly formation. Many French soldiers fired before they were within range of striking the British. Wolfe organised his troops in two lines stretching 1 mile across the Plains of Abraham. They were ordered to load their Brown Bess muskets with two bullets to obtain maximum power and hold their fire until the French soldiers came within 40 paces of the British ranks. When Montcalm's army was within range of the British, their volley was powerful and nearly all bullets hit their targets, devastating the French ranks. The French fled the Plains of Abraham in a state of utter confusion while they were pursued by members of the Scottish Fraser regiment and other British forces. Despite being cut down by musket fire from the Canadians and their indigenous allies, the British vastly outnumbered these opponents and won the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.[110] General Wolfe was mortally wounded in the chest early in the battle so the command fell to James Murray, who would become the lieutenant governor of Quebec after the war. The Marquis de Montcalm was also severely wounded later in the battle and died the following day. The French abandoned the city and French Canadians led by the Chevalier de Levis staged a counteroffensive on the Plains of Abraham in the spring of 1760, with initial success at the Battle of Sainte-Foy.[111] During the subsequent siege of Quebec, however, Lévis was unable to retake the city, largely because of British naval superiority following the Battle of Neuville and the Battle of Restigouche, which allowed the British to be resupplied but not the French. The French forces retreated to Montreal in the summer of 1760, and after a two-month campaign by overwhelming British forces, they surrendered on 8 September, essentially ending the French Empire in North America. As the Seven Years War was not yet over in Europe, the British put all of New France under a military regime while awaiting the results. This regime would last from 1760 to 1763.

Seeing French and Indian defeat, in 1760, the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy resigned from the war and negotiated the Treaty of Kahnawake with the British. Among its conditions was their unrestricted travel between Canada and New York, as the nations had extensive trade between Montreal and Albany as well as populations living throughout the area.[112]

In 1762, towards the end of the war, French forces attacked St. John's, Newfoundland. If successful, the expedition would have strengthened France's hand at the negotiating table. Although they took St. John's and raided nearby settlements, the French forces were eventually defeated by British troops at the Battle of Signal Hill. This was the final battle of the war in North America, and it forced the French to surrender to Lieutenant Colonel William Amherst. The victorious British now controlled all of eastern North America.

The history of the Seven Years' War in North America, particularly the Expulsion of the Acadians, the siege of Quebec, the death of Wolfe, and the siege of Fort William Henry generated a vast number of ballads, broadsides, images, and novels (see Longfellow's Evangeline, Benjamin West's The Death of General Wolfe, James Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans), maps and other printed materials, which testify to how this event held the imagination of the British and North American public long after Wolfe's death in 1759.[113]

South America

In South America (1763), the Portuguese conquered most of the Rio Negro valley,[114][115] and repelled a Spanish attack on Mato Grosso (in the Guaporé River).[116][117]

Between September 1762 and April 1763, Spanish forces led by don Pedro Antonio de Cevallos, Governor of Buenos Aires (and later first Viceroy of the Rio de la Plata) undertook a campaign against the Portuguese in the Banda Oriental, now Uruguay and south Brazil. The Spanish conquered the Portuguese settlement of Colonia do Sacramento and Rio Grande de São Pedro and forced the Portuguese to surrender and retreat.

Under the Treaty of Paris (1763), Spain had to return to Portugal the settlement of Colonia do Sacramento, while the vast and rich territory of the so-called "Continent of S. Peter" (the present-day Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul) would be retaken from the Spanish army during the undeclared Hispano-Portuguese war of 1763–1777.[118][119][120][121]

As consequence of the war the Valdivian Fort System, a Spanish defensive complex in southern Chile, was updated and reinforced from 1764 onwards. Other vulnerable localities of Colonial Chile such as Chiloé Archipelago, Concepción, Juan Fernández Islands, and Valparaíso were also made ready for an eventual English attack.[122][123] The war contributed also to a decision to improve communications between Buenos Aires and Lima resulting in the establishment of a series of mountain shelters in the high Andes called Casuchas del Rey.[124]

India

.jpg.webp)

In India, the outbreak of the Seven Years' War in Europe renewed the long running conflict between the French and the British trading companies for influence on the subcontinent. The French allied themselves with the Mughal Empire to resist British expansion. The war began in Southern India but spread into Bengal, where British forces under Robert Clive recaptured Calcutta from the Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah, a French ally, and ousted him from his throne at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. In the same year, the British also captured Chandernagar, the French settlement in Bengal.[125]

In the south, although the French captured Cuddalore, their siege of Madras failed, while the British commander Sir Eyre Coote decisively defeated the Comte de Lally at the Battle of Wandiwash in 1760 and overran the French territory of the Northern Circars. The French capital in India, Pondicherry, fell to the British in 1761; together with the fall of the lesser French settlements of Karikal and Mahé this effectively eliminated French power in India.[126]

West Africa

In 1758, at the urging of an American merchant, Thomas Cumming, Pitt dispatched an expedition to take the French settlement at Saint-Louis, Senegal. The British captured Senegal with ease in May 1758 and brought home large amounts of captured goods. This success convinced Pitt to launch two further expeditions to take the island of Gorée and the French trading post on the Gambia. The battles in West Africa were ultimately a series of British expeditions against wealthy French colonies. The British and French had been competing for influence in the Gambia region following the acquisition of James Island in 1664 by the English from the Dutch. The loss of these valuable colonies to the British further weakened the French economy.[127]

Neutral nations during the war

Ottoman Empire

Despite being one of the major European powers during this time, the Ottoman Empire was notably neutral during the Seven Years' War. Following their military stalemate with the Russian Empire and their subsequent victory over the Holy Roman Empire (and Austria to an extent), during the Austro-Russian-Turkish War (1735–1739), and the signing of the Treaty of Belgrade, the Ottoman Empire enjoyed a generation of peace due to Austria and Russia contending with the rise of Prussia in Eastern Europe. During the war, King Frederick II of Prussia, better known to history as Frederick the Great, had made diplomatic overtures with the Ottoman Sultan, Mustafa III for years, up to the outbreak of war, to bring the empire into the war on the side of Prussia, Great Britain, and their other allies but he was unsuccessful. However, the Sultan was persuaded by his court not to join the war, primarily by his Grand Vizier, Koca Ragıb Pasha, who was quoted as saying.

"Our state looks like a majestic and mighty lion from afar. However, a closer look at this lion reveals that it has aged—its teeth have fallen out—its claws have fallen. So, let's leave this old lion to rest for a while."

Therefore, the Ottoman Empire avoided the major wars that would follow, including the Seven Years' War. The Ottoman Empire, or more accurately its leaders, recognised its internal problems. The previous wars had cost the empire greatly, both in terms of resources and finance, they were facing rebellions from nationalistic uprisings, notably from the Beyliks, and Persia had been reunited under Karim Khan Zand. That said, the Ottoman Empire would launch an abortive invasion of Hungary with 100,000 troops in 1763, contributing to the end of the war.[128]

Persia

Persia ended up under the rule of the Zand dynasty during the period of the Seven Years' War. Like the Ottoman Empire, they were also neutral during the war. They had more pressing matters to attend to. Karim Khan Zand, was busy playing politics and was in the process of legitimising his claim to the Persian throne by placing a puppet king on the throne, Ismail III, the grandson of the last Safavid king, in 1757.[129] However, by 1760, he had managed to eliminate all other potential claimants to the throne as well as Ismail III and had established himself as the head of his own dynasty, the aforementioned Zand dynasty.[130]

Dutch Republic

The Dutch Republic had played a central role in the wars against Louis XIV's France[lower-alpha 4] in the late 1600s and early 1700s, and doing this had proved to be very expensive. This motivated the Dutch to try to stay out of major 18th-century European conflicts like the War of the Polish Succession and War of the Austrian Succession.[131] Grand Pensionary Laurens van de Spiegel, in 1782, blamed the earlier generations for placing too heavy a burden on their descendants by waging wars on credit.

"Every new war is a step closer to taking away from the descendants the means of defence they need."

It was precisely for this reason that Pieter Steyn, Grand Pensionary of Holland from 1749 to 1772, wanted the Republic to align its foreign policy with the state of its finances. Specifically, this meant that Holland should do everything possible to ensure that the Republic did not become involved in the Franco-British dispute, despite animosity towards France and being a long-time ally of Britain. This was not going to be easy, because London was exerting great pressure on the States General to make troops available for the defence of Great Britain as soon as hostilities with France were to occur, and as the daughter of George II, it would be almost impossible for Princess Anne, regent in the Dutch Republic for William V of Orange, to refuse the requested help. However, the wealthy merchants of Amsterdam did not want to go to war for Britain's interests. Together with French assurances that King Louis XV did not want to multiply his enemies and that it was the Prussians who broke the peace, this made it possible for Steyn to declare the Republic neutral.[132]

Despite British threats, the detention of many Dutch merchant ships by the British, and various incidents, as when Dutch soldiers stationed in the Austrian Netherlands fired celebratory gunshots in support of the Prussians after the Battle of Breslau, the Dutch Republic managed to preserve its neutrality during the Seven Years' War. It owed this to the memory of what it had been and what it could possibly become again, namely a land and naval power of the first rank. For the Prussian king, the Republic was an important ally with view of securing his scattered possessions along the Dutch eastern border, and for George II, the Dutch seaports provided the most secure link with Hanover. For their part, the British were concerned that their supremacy at sea would be jeopardised if the Republic were to lend its cooperation to a French plan for joint maritime action by the French, Spanish, Danish and Dutch fleets. In addition, the government in London had not yet given up hope to restore the disrupted relationship with the Dutch by including them in a military and political bloc formed by Britain, Hanover, Prussia and the Dutch Republic. When the States of Holland announced in the States General on 12 January 1759 that they had decided to equip 25 warships, at their own expense if need be, and Princess Anna also died that same evening, the British government realised that it should not let things get out of hand by inflicting too much damage on Dutch trade. It resigned itself to the fact that the Republic persisted in its neutral stance.[132][133]

Unofficially, the Dutch East India Company would try to undermine or even prevent British domination in India during the Third Carnatic War.[134]

Denmark–Norway