Gender inequality in India

Gender inequality in India refers to health, education, economic and political inequalities between men and women in India.[1] Various international gender inequality indices rank India differently on each of these factors, as well as on a composite basis, and these indices are controversial.[2][3]

Gender inequalities, and their social causes, impact India's sex ratio, women's health over their lifetimes, their educational attainment, and even the economic conditions too. It also prevents the institution of equal rape laws for men.[4][5] Gender inequality in India is a multifaceted issue that primarily concerns men, that places men at a disadvantage, or that it affects each gender equally.[6] However, when India's population is examined as a whole, women are at a disadvantage in several important ways. Although the constitution of India grants men and women equal rights, gender disparities remain.

Research shows gender discrimination mostly in favor of men in many realms including the workplace.[7][8] Discrimination affects many aspects in the lives of women from career development and progress to mental health disorders. While Indian laws on rape, dowry and adultery have women's safety at heart,[9] these highly discriminatory practices are still taking place at an alarming rate, affecting the lives of many today.[10][11]

Gender statistics

The following table compares the population wide data for the two genders on various inequality statistical measures, and according to The World Bank's Gender Statistics database for 2012.[12]

| Gender Statistic Measure[12] | Females (India) |

Males (India) |

Females (World) |

Males (World) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant mortality rate, (per 1,000 live births) | 44.3 | 43.5 | 32.6 | 37 |

| Life expectancy at birth, (years) | 68 | 64.5 | 72.9 | 68.7 |

| Expected years of schooling | 11.3 | 11.8 | 11.7 | 12.0 |

| Primary school completion rate, (%) | 96.6 | 96.3 | [13] | |

| Lower secondary school completion rate, (%) | 76.0 | 77.9 | 70.2 | 70.5 |

| Secondary school education, pupils (%) | 46 | 54 | 47.6 | 52.4 |

| Ratio of females to males in primary and secondary education (%) | 0.98 | 1.0 | 0.97 | 1.0 |

| Secondary school education, gender of teachers (% ) | 41.1 | 58.9 | 51.9 | 48.1 |

| Account at a formal financial institution, (% of each gender, age 15+) | 26.5 | 43.7 | 46.6 | 54.5 |

| Deposits in a typical month, (% with an account, age 15+) | 11.2 | 13.4 | 13.0 | 12.8 |

| Withdrawals in a typical month, (% with an account, age 15+) | 18.6 | 12.7 | 15.5 | 12.8 |

| Loan from a financial institution in the past year, (% age 15+) | 6.7 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 10.0 |

| Outstanding loan from banks for health or emergencies, (% age 15+) | 12.6 | 15.7 | 10.3 | 11.6 |

| Outstanding loan from banks to purchase a home, (% age 15+) | 2.26 | 2.35 | 6.6 | 7.4 |

| Unemployment, (% of labour force, ILO method) | 4 | 3.1 | [13] | |

| Unemployment, youth (% of labour force ages 15–24, ILO method) | 10.6 | 9.4 | 15.1 | 13.0 |

| Ratio of females to males youth unemployment rate (% ages 15–24, ILO method) | 1.13 | 1.0 | 1.14 | 1.0 |

| Employees in agriculture, (% of total labour) | 59.8 | 43 | [13] | |

| Employees in industry, (% of total labour) | 20.7 | 26 | [13] | |

| Self-employed, (% employed) | 85.5 | 80.6 | [13] | |

| Cause of death, by non-communicable diseases, ages 15–34, (%) | 32.3 | 33.0 | 29.5 | 27.5 |

| Life expectancy at age 60, (years) | 18.0 | 15.9 | [13] | |

Global rankings of India

Various groups have ranked gender inequalities around the world. For example, the World Economic Forum publishes a Global Gender Gap Index score for each nation every year. The index focuses not on empowerment of women, but on the relative gap between men and women in four fundamental categories – economic participation, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment.[14] It includes measures such as estimated sex-selective abortion, number of years the nation had a female head of state, female to male literacy rate, estimated income ratio of female to male in the nation, and several other relative gender statistic measures. It does not include factors such as crime rates against women versus men, domestic violence, honor killings or such factors. Where data is unavailable or difficult to collect, World Economic Forum uses old data or makes a best estimate to calculate the nation's Global Gap Index (GGI).[14]

According to the Global Gender Gap Report released by the World Economic Forum (WEF) in 2011, India was ranked 113 on the Gender Gap Index (GGI) among 135 countries polled.[15] Since then, India has improved its rankings on the World Economic Forum's Gender Gap Index (GGI) to 105/136 in 2013.[14] When broken down into components of the GGI, India performs well on political empowerment, but is scored to be as bad as China on sex-selective abortion. India also scores poorly on overall female to male literacy and health rankings. India with a 2013 ranking of 101 had an overall score of 0.6551, while Iceland, the nation that topped the list, had an overall score of 0.8731 (no gender gap would yield a score of 1.0).[14]

Alternate measures include OECD's Social Institutions Gender Index (SIGI), which ranked India at 56th out of 86 in 2012, which was an improvement from its 2009 rank of 96th out of 102. The SIGI is a measure of discriminatory social institutions that are drivers of inequalities, rather than the unequal outcomes themselves.[16] Similarly, UNDP has published the Gender Inequality Index and ranked India at 132 out of 148 countries.

- Problems with indices

Scholars[3][17] have questioned the accuracy, relevance and validity of these indices and global rankings. For example, Dijkstra and Hanmer[2] acknowledge that global index rankings on gender inequality have brought media attention, but suffer from major limitations. The underlying data used to calculate the index are dated, unreliable and questionable. Further, a nation can be and are being ranked high when both men and women suffer from equal deprivation and lack of empowerment.[2] In other words, nations in Africa and the Middle East where women have lower economic participation, lower educational attainment, and poorer health and high infant mortalities, rank high if both men and women suffer from these issues equally. If one's goal is to measure progress, prosperity and empowerment of women with equal gender rights, then these indices are not appropriate for ranking or comparing nations. They have limited validity.[2] Instead of rankings, the focus should be on measuring women's development, empowerment and gender parity, particularly by relevant age groups such as children and youth.[18][19] Nevertheless, it is widely accepted that India along with other developing countries have high gender inequality and lower women's empowerment than developed nations.[20][21]

Birth

The cultural construct of Indian society which reinforces gender bias against men and women, with varying degrees and variable contexts against the opposite sex,[22] has led to the continuation of India's strong preference for male children. Female infanticide and sex-selective abortion is adopted and strongly reflects the societally low status of Indian women. Census 2011 shows decline of girl population (as a percentage to total population) under the age of seven, with activists estimating that eight million female fetuses may have been aborted in the past decade.[23] The 2005 census shows infant mortality figures for females and males are 61 and 56, respectively, out of 1000 live births,[24] with females more likely to be aborted than males due to biased attitudes, cultural stereotypes, insecurity, etc.

A decline in the child sex ratio (0–6 years) was observed with India's 2011 census reporting that it stands at 914 females against 1,000 males, dropping from 927 in 2001 – the lowest since India's independence.[25]

The demand for sons among wealthy parents is being satisfied by the medical community through the provision of illegal service of fetal sex-determination and sex-selective abortion. The financial incentive for physicians to undertake this illegal activity seems to be far greater than the penalties associated with breaking the law.[26]

Disparities in education

Education is not equally attained by Indian women. Although literacy rates are increasing, the female literacy rate lags behind the male literacy rate.

Literacy for females stands at 65.46%, compared to 82.14% for males.[27] An underlying factor for such low literacy rates are parents' perceptions that education for girls are a waste of resources as their daughters would eventually live with their husbands' families. Thus, there is a strong belief that due to their traditional duty and role as housewives, daughters would not benefit directly from the education investment.[28]

Programs like Ashram schools for tribes, programs for low literacy districts, and scholarships to promote higher education like the Pre-Matric and Post-Matric Scholarship, Rajiv Gandhi National Fellowship, etc. have been recently installed to promote education. Traditional beliefs regarding women's education, especially in rural and tribal communities in India prevent women from taking advantage of these resources.[29]

For women in rural or tribal communities the educational disparities are even larger. In 2011, for the state of Jharkhand, male scheduled tribes (STs) had a literacy rate of around 68% whereas female STs had a literacy rate of around 46%.[30] Tribal women lack access to educational institutions and are isolated from urban society, which restrict them from obtaining economic opportunities and mobility. Tribal women in India are often unskilled and are perceived by general society as chaotic and willing to perform sexual intercourse. As a result, tribal women who attempt to integrate within rural or urban societies end up as sexual workers or take up physical manual labor jobs.[29]

Adulthood and onwards

Discrimination against women has contributed to gender wage differentials, with Indian women on average earning 64% of what their male counterparts earn for the same occupation and level of qualification.[31]

This has led to their lack of autonomy and authority. Although equal rights are given to women, equality may not be well implemented. In practice, land and property rights are weakly enforced, with customary laws widely practiced in rural areas.[32]

Economic inequalities

Labour participation and wages

The labour force participation rate of women was 80.7% in 2013.[33] Nancy Lockwood of Society for Human Resource Management, the world's largest human resources association with members in 140 countries, in a 2009 report wrote that female labour participation is lower than men, but has been rapidly increasing since the 1990s. Out of India's 397 million workers in 2001, 124 million were women, states Lockwood.[34]

Over 50% of Indian labour is employed in agriculture. A majority of rural men work as cultivators, while a majority of women work in livestock maintenance, egg and milk production. Rao[35] states that about 78 percent of rural women are engaged in agriculture, compared to 63 percent of men. About 37% of women are cultivators, but they are more active in the irrigation, weeding, winnowing, transplanting, and harvesting stages of agriculture. About 70 percent of farm work was performed by women in India in 2004.[35] Women's labour participation rate is about 47% in India's tea plantations, 46% in cotton cultivation, 45% growing oil seeds and 39% in horticulture.[36]

There is wage inequality between men and women in India. The largest wage gap was in manual ploughing operations in 2009, where men were paid ₹ 103 per day, while women were paid ₹ 55, a wage gap ratio of 1.87. For sowing the wage gap ratio reduced to 1.38 and for weeding 1.18.[37] For other agriculture operations such as winnowing, threshing, and transplanting, the men to female wage ratio varied from 1.16 to 1.28. For sweeping, the 2009 wages were statistically same for men and women in all states of India.[37]

Access to credit

Although laws are supportive of lending to women and microcredit programs targeted to women are prolific, women often lack collateral for bank loans due to low levels of property ownership and microcredit schemes have come under scrutiny for coercive lending practices. Although many microcredit programs have been successful and prompted community-based women's self-help groups, a 2012 review of microcredit practices found that women are contacted by multiple lenders and, as a result, take on too many loans and overextend their credit. The report found that financial incentives for the recruiters of these programs were not in the best interest of the women they purported to serve.[38] The result was a spate of suicides by women who were unable to pay their debts.[39]

Property rights

Women have equal rights under the law to own property and receive equal inheritance rights, but in practice, women are at a disadvantage. This is evidenced in the fact that 70% of rural land is owned by men.[40] Laws, such as the Married Women Property Rights Act of 1974 protect women, but few seek legal redress.[41] Although the Hindu Succession Act of 2005 provides equal inheritance rights to ancestral and jointly owned property, the law is weakly enforced, especially in Northern India.

Tribal women's property rights

Tribal women face both social and legal inequalities with property ownership. Tribal communities in India rely on their land for economic stability since their lifestyle and source of income is tied to the agricultural industry. The International Labour Organization Convention 169 guarantees tribal communities rights to their own land. It enforces policies that requires free, advanced, and informed consent to utilize tribal land for development and ensures that the process is inclusive and accommodating to tribal communities that occupy the land. This includes the option for tribals to reacquire their land after it has been restored. Several other policies have been passed in rural areas of India to protect tribal land, such as the Chota Nagpur Tenancy Act, the Santhal Pargana Tenancy Act, and Wilkinson's Rule. However, contracts signed between tribal communities and private parties or state governments are often violated, leaving families displaced.[42]

Additionally, the aforementioned land protection policies have been identified to exclude tribal women. Tribal women in India hold status primarily due to their acting roles as forest-based gatherers, and are especially impacted by inadequate property protection policies.[43] Due to displacement, tribal women have been found to face rehabilitation, discrimination within caste-based rural communities. One of the major consequences of the marginalization of tribal communities, for women, has been job security. Resettlement policies for tribal families often only offer monetary compensation and job security to male workers, or households supported by women.[44]

Occupational inequalities

Entrepreneurship

Different studies have examined the women in entrepreneurship roles and the attitudes and outcomes surrounding their participation in this informal economic sector.[45][46] A 2011 study published by Tarakeswara Rao et al. in the Journal of Commerce indicated that almost 50% of the Indian population consists of women, yet fewer than 5% of businesses are owned by women.[45] In fact, in terms of entrepreneurship as an occupation, 7% of total entrepreneurs in India are women, while the remaining 93% are men.[45] Another 2011 study conducted by Colin Williams and Anjula Gurtoo, published in the International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship describes women entrepreneurs face several barriers in the development of their work due to different factors.[46] Some of these barriers include lacking access to institutional credit which presents negative consequences in terms of expanding businesses.[46] In addition, women in this realm may lack a formal designated space for their occupational work and can face gendered violence due to their more open presence in society.[46] The other major challenge for women entrepreneurs is the type of activities performed in their occupational role.[46] Oftentimes, these activities may be quite limited, corresponding to traditional gendered roles, performing business ventures such as selling fruit or flowers at temples in India, which hinders the further development of women entrepreneurs beyond a certain point.[46]

This study by Colin Williams and Anjula Gurtoo also gathered data in the form of personal interviews with various women working in an entrepreneurship realm.[46] In the study, the categories of occupation among women entrepreneurs were defined as the following: home helpers, vendors, office assistants, and shop assistants.[46] The findings from the study indicated that these entrepreneurial women did not consider job security to be an area of concern like some of their counterparts working in other industries.[46] However, a primary concern for these women was the lack of alternate employment which initially prompted them to pursue entrepreneurial work, though economic benefits were slowly acquired after gaining a foothold in the industry.[46]

Teaching

.jpg.webp)

There are gender differences in the number of teachers and their impact on education.[47] During the mid-1970s, females were 25% of teachers, increasing to 43% by 2008.[47] Compared to male teachers, female teachers had lower educational qualifications, though a slightly greater proportion of female teachers had received teacher training.[47] In addition, on average, more female teachers in the study compared to male teachers had over ten years of teaching experience.[47]

Scientific professions

Multiple factors may contribute to the barriers and discrimination that women in face in science, although the situation has improved over the years.[48][49]

A 2003 study of four science and technology higher education institutions in India found that 40% of female faculty members felt some form of gender discrimination in their respective institutions, favoring male faculty members.[48] In addition, in terms of hiring practices, the interview committees of these institutions asked female applicants how they would balance their family with work, and why they were applying for a position rather than being a homemaker.[48] Discriminatory hiring practices in favor of men were also pursued due to beliefs that women would be less committed to work after marriage.[48]

Military service

Women are not allowed to have combat roles in the armed forces. According to a study carried out on this issue, a recommendation was made that female officers be excluded from induction in close combat arms. The study also held that a permanent commission could not be granted to female officers since they have neither been trained for command nor have they been given the responsibility so far, although changes are appearing. Women are starting to play important roles in army and the previous defence minister was a woman.[50]

On 17 February 2020 the Supreme Court of India said that women officers in the Indian Army can get command positions at par with male officers. The court said that the government's arguments against it were discriminatory, disturbing and based on stereotype. The court also said that permanent commission should be available to all women, regardless of their years of service, and the order must be implemented in 3 months.[51] The government had earlier said that troops, mostly men, won't accept women commanders.[52] However, women are now taking up combat roles in the Indian Air Force with Avani Chaturvedi, Mohana Singh Jitarwal, and Bhawana Kanth being the first 3 women fighter pilots.[53] Despite the Indian Army and the Air Force allowing women to be in a combat role, the Indian Navy is still against the idea of putting women in warships as sailors, even though they fly on maritime patrol aircraft like P8I and IL 38[54]

Education inequalities

Schooling

India is on target to meet its Millennium Development Goal of gender parity in education by 2015.[55] UNICEF's measure of attendance rate and Gender Equality in Education Index (GEEI) capture the quality of education.[56] Despite some gains, India needs to triple its rate of improvement to reach GEEI score of 95% by 2015 under the Millennium Development Goals.

In rural India girls continue to be less educated than boys.[57] Recently, many studies have investigated underlying factors that contribute to greater or less educational attainment by girls in different regions of India.[58] One 2017 study performed by Adriana D. Kugler and Santosh Kumar, published in Demography, examined the role of familial size and child composition in terms of gender of the first-born child and others on the educational attainment achieved in a particular family.[59] According to this study, as the family size increased by each additional child after the first, on average there was quarter of a year decrease in overall years of schooling, with this statistic disfavoring female children in the family compared to male children.[59] In addition, the educational level of the mother in the family also plays a role in the educational attainment of the children, with the study indicating that in families with mothers that had a lower educational level, the outcomes tended to more disadvantageous for educational attainment of the children.[59]

Secondary education

In examining educational disparities between boys and girls, the transition from primary to secondary education displays an increase in the disparity gap, as a greater percentage of females compared to males drop out from their educational journey after the age of twelve.[60] A particular 2011 study conducted by Gaurav Siddhu, published in the International Journal of Educational Development, investigated the statistics of dropout in the secondary school transition and its contributing factors in Rural India.[61] The study indicated that among the 20% of students who stopped schooling after primary education, near 70% of these students were females.[61] This study also conducted interviews to determine the factors influencing this dropout in Rural India.[61] The results indicated that the most common reasons for girls to stop attending school was the distance of travel and social reasons.[61] In terms of distance of travel, families expressed fear for the safety and security of girls, traveling unaccompanied to school every day.[61] In rural areas the social reasons also consisted of how families viewed their daughter's role of belonging in her husband's house after marriage, with plans for the daughter's marriage during the secondary school age in some cases.[61]

Post-secondary education

Participation in post-secondary education for girls in India has changed over time.[62] One 2012 examination conducted by Rohini Sahni and Kalyan Shankar, published in High Education, investigated the aspect of inclusiveness for girls in the realm of higher education.[62] The source indicates that overall participation for girls in higher education has gone up over time, especially in recent years.[62] However, there are persisting disparities in terms of spread across disciplines.[62] While boys tend to be better represent all educational disciplines, girls tend to have concentration in selective disciplines, while lacking representation in other educational realms.[62]

There has also been research on the dropout statistics across time in higher education.[63] A 2007 source authored by Sugeeta Upadhyay in the journal Economic and Political Weekly, described that the dropout rate in higher education in greater for boys rather than girls.[63] This trend is reversed in secondary education with dropout rates being greater for girls versus boys.[63] The article suggests that the dropout rate in higher education could be explained by the sense of necessity and urgency that boys may feel to acquire employment.[63] Thus, as employment is attained, boys may be more likely to drop out compared to girls in higher education institutions, as the employment urgency could be less pressing for girls.[63]

Literacy

Though it is gradually rising, the female literacy rate in India is lower than the male literacy rate.[64] According to Census of India 2011, literacy rate of females is 65.46% compared to males which is 82.14%. Compared to boys, far fewer girls are enrolled in the schools, and many of them drop out.[64] According to the National Sample Survey Data of 1997, only the states of Kerala and Mizoram have approached universal female literacy rates. According to majority of the scholars, the major factor behind the improved social and economic status of women in Kerala is literacy.[64] From 2006 to 2010, the percent of females who completed at least a secondary education was almost half that of men, 26,6% compared to 50.4%.[33] In the current generation of youth, the gap seems to be closing at the primary level and increasing at the secondary level. In rural Punjab, the gap between girls and boys in school enrollment increases dramatically with age as demonstrated in National Family Health Survey-3 where girls age 15–17 in Punjab are 10% more likely than boys to drop out of school.[65] Although this gap has been reduced significantly, problems still remain in the quality of education for girls where boys in the same family will be sent to higher-quality private schools and girls sent to the government school in the village.[66]

Reservations for female students

Under the Non-Formal Education program, about 40% of the centres in states and 10% of the centres in UTs are exclusively reserved for females.[57] As of 2000, about 0.3 million NFE centres were catering to about 7.42 million children, out of which about 0.12 million were exclusively for girls.[57] Certain state level engineering, medical and other colleges like in Odisha have reserved 30% of their seats for females.[67] The Prime Minister of India and the Planning Commission also vetoed a proposal to set up an Indian Institute of Technology exclusively for females.[68] Although India had witnessed substantial improvements in female literacy and enrollment rate since the 1990s, the quality of education for female remains to be heavily compromised.

Health and survival inequalities

On health and survival measures, international standards consider the birth sex ratio implied sex-selective abortion, and gender inequality between women's and men's life expectancy and relative number of years that women live compared to men in good health by taking into account the years lost to violence, disease, malnutrition or other relevant factors.[69]

Sex-selective abortion

In North America and Europe the birth sex ratio of the population ranges between 103 and 107 boys per 100 girls; in India, China and South Korea, the ratio has been far higher. Women have a biological advantage over men for longevity and survival; however, there have been more men than women in India and other Asian countries.[71][72] This higher sex ratio in India and other countries is considered as an indicator of sex-selective abortion.

The 2011 Census birth sex ratio for its States and Union Territories of India, in 0 to 1 age group, indicated Jammu & Kashmir had birth sex ratio of 128 boys to 100 girls, Haryana of 120, Punjab of 117, and the states of Delhi and Uttarakhand to be 114.[70] This has been attributed to increasing misuse and affordability of fetus sex-determining devices, such as ultrasound scan, the rate of female foeticide is rising sharply in India. Female infanticide (killing of girl infants) is still prevalent in some rural areas.[64]

Patnaik estimates from the birth sex ratio that an expected 15 million girls were not born between 2000 and 2010.[73] MacPherson, in contrast, estimates that sex-selective abortions account for about 100,000 missing girls every year in India.[74]

Girl babies are often killed for several reasons, the most prominent one being financial reasons. The economical reasons include earning of power as men as are the main income-earners, potential pensions, as when the girl is married she would part ways with her family and the most important one, the payment of dowry. Even though it's illegal by Indian law to ask for dowry, it is still a common practice in certain socio-economic classes which leads to female infanticide, as the baby girls are seen as an economic burden.[75]

Gender selection and selective abortion were banned in India under Pre-conception and Pre-natal Diagnostics Technique Act in 1994.[76] The practice continues illegally. Other institutional efforts, such as advertisements calling female foeticides a sin by the Health Ministry of India and annual Girl Child Day[77] can be observed to raise the status of girls and to combat female infanticide.

Health

Immunization rates for 2-year-olds was 41.7% for girls and 45.3% for boys according to the 2005 National Family Health Survey-3, indicating a slight disadvantage for girls.[78] Malnutrition rates in India are nearly equal in boys and girls.

The male to female suicide ratio among adults in India has been about 2:1.[79] This higher male to female ratio is similar to those observed around the world.[80] Between 1987 and 2007, the suicide rate increased from 7.9 to 10.3 per 100,000,[81] with higher suicide rates in southern and eastern states of India.[82] In 2012, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and West Bengal had the highest proportion of female suicides.[79] Among large population states, Tamil Nadu and Kerala had the highest female suicide rates per 100,000 people in 2012.

Mental health concerns

Some studies in south India have shown found that gender disadvantages, such as negative attitudes towards women's empowerment are risk factors for suicidal behavior and common mental disorders like anxiety and depression.[83] These mental health aspects can be studied in different environments for women such as in the home, the workforce, and the educational institutions due to varying social conditions that contribute to the development of mental illnesses in some cases.[84][85] According to a 2001 study performed by U. Vindhya et al., published in Economic and Political Weekly, women tend to have greater suffering from depression and somatoform and dissociative disorders compared to men in the study.[86] Furthermore, the research attributed depressive symptoms to social interactions both in the workplace and home that fostered a sense of learned helplessness.[86] This stems from feelings of powerlessness in different types of relationships that are male-dominated and do not offer equity for women.[86] Other social stressors that contribute as influences in mental illnesses include marriage, pregnancy, family, with pressure to fit into certain traditional roles ascribed to women in India.[86]

Furthermore, another 2006 study conducted by Vikram Patel et al., published in Archives of General Psychiatry, further examined specific aspects of gender disadvantages that contributed to common mental disorders.[87] The areas investigated within gender disadvantages included marital history, life experience of various forms of violence in relationship with spouses, autonomy regarding a woman's personal choices, level of engagement outside the home, and social support from family during times of difficulty.[87] Women with situations in which they were ostracized from their community, for example due to being divorced or widowed, the risk for common mental disorders grew significantly.[87] The results of the study indicated that for all factors represented, if these contributed in a negative manner, there was a higher occurrence of common mental disorders in rural and periurban communities in India.[87]

Gender-based violence

Domestic violence

Domestic violence,[89][90] rape and dowry-related violence are sources of gender violence.[64][91] Domestic violence has historically been one of the largest social issues in India. One study found that 4 out of 10 women in India have experienced domestic violence in their lifetime and 3 out of 10 women experienced domestic violence in the past year.[92] Victims of domestic violence often continue to stay silent out of shame, fear of retaliation, and possibly social isolation within their communities.[93] In a survey including women of different castes from a rural village in New Delhi, Barwala, it was identified that the most common factor of domestic violence was alcoholism. It was also found that in cases where a husband committed violent acts against his wife, residing members of the joint family would often instigate the abuse.

Rape

According to the National Crime Records Bureau 2013 annual report, 24,923 rape cases were reported across India in 2012; however, this number is likely to be larger due to many cases that go unreported.[94] Out of these, 24,470 were committed by relative or neighbour; in other words, the victim knew the alleged rapist in 98 per cent of the cases.[95] Compared to other developed and developing countries, incidence rates of rape per 100,000 people are quite low in India.[96][97] India records a rape rate of 2 per 100,000 people,[94][98] compared to 8.1 rapes per 100,000 people in Western Europe, 14.7 per 100,000 in Latin America, 28.6 in the United States, and 40.2 per 100,000 in Southern African region.[99] However, some rape cases, where there was no bond between the victim and the rapist, have led to big protests in India as well as a lot of international media coverage.[100] One of the most debated cases, known as the 2012 Delhi gang rape and murder, a 23-year-old female was gang-raped, tortured and later died from the fatality of her injuries. Following the news of the case and later the death of the victim, big protests[101] spread across the whole country, where protesters demanded safety for women and legal justice for rape victims.

Dowry-related and honor killings

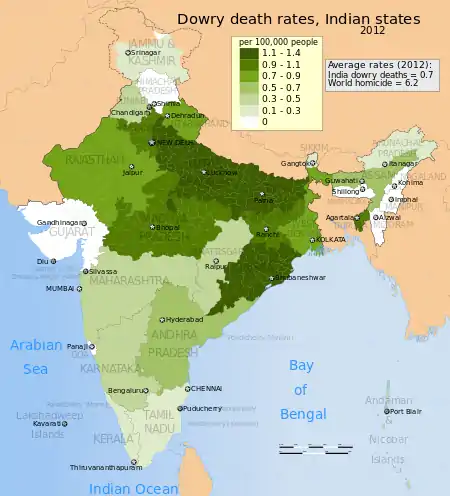

Other sources of gender violence include those that are dowry-related and honor killings. NCRB report states 8,233 dowry deaths in the country in 2012.[102] Honor killings are violence where the woman's behavior is linked to the honor of her whole family; in extreme cases, family members kill her. Honor killings are difficult to verify, and there is a dispute whether social activists are inflating numbers. In most cases, honor killings are linked to the woman marrying someone that the family strongly disapproves of.[103] Some honor killings are the result of extrajudicial decisions made by traditional community elders such as "khap panchayats," unelected village assemblies that have no legal authority. Estimates place 900 deaths per year (or about 1 per million people). Honor killings are found in the Northern states of Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh.[103]

Witch hunting

More extreme forms of violence are seen within certain areas of rural India. Witch hunting has been a common issue among rural tribal women, especially within the state of Jharkhand. It refers to violence or killings that occur when a woman is suspected or accused of causing diseases, illnesses, insufficient crop yields, etc. The concept of witch hunting stems from the idea of spirits, which represent the good, and witches, which represent the bad, and is a central concept of tribal culture. Due to the lack of educational and healthcare infrastructure in rural areas, especially tribal villages in Jharkhand, residents will often rely on superstitious figures in the village. The misinformation results in family members and neighbors using female figures in their society as scapegoats for these issues. Due to the social and gendered nature of the crime, it is often difficult to file reports and investigate witchcraft-related crimes.[44]

A study found that states with higher levels of gender inequality, measured by female literacy rates, women labor participation, and gaps in education and health services, tend to have higher rates of gender-based crime.[104]

Political inequalities

This measure of gender inequality considers the gap between men and women in political decision making at the highest levels.[105]

On this measure, India has ranked in top 20 countries worldwide for many years, with 9th best in 2013 – a score reflecting less gender inequality in India's political empowerment than Denmark, Switzerland, Germany, France and United Kingdom.[106][107] From the prime minister to chief ministers of various states, Indian voters have elected women to its state legislative assemblies and national parliament in large numbers for many decades.

Women turnout during India's 2014 parliamentary general elections was 65.63%, compared to 67.09% turnout for men.[108] In 16 states of India, more women voted than men. A total of 260.6 million women exercised their right to vote in April–May 2014 elections for India's parliament.[108]

India passed 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments in 1993, which provides for 33 per cent quotas for women's representation in the local self-government institutions. These Amendments were implemented in 1993. This, suggests Ghani et al., has had strong effects for empowering women in India in many spheres.[109]

Reasons for gender inequalities

Gender inequality has been a historic worldwide phenomena, not a human invention and based on gender assumptions.[110] It is linked to kinship rules rooted in cultures and gender norms that organizes human social life, human relations, as well as promotes subordination of women in a form of social strata.[110] Amartya Sen highlighted the need to consider the socio-cultural influences that promote gender inequalities[111][112] In India, cultural influences favor the preference for sons for reasons related to kinship, lineage, inheritance, identity, status, and economic security. This preference cuts across class and caste lines, and it discriminates against girls.[113] In extreme cases, the discrimination takes the form of honour killings where families kill daughters or daughters-in-law who fail to conform to gender expectations about marriage and sexuality.[114] When a woman does not conform to expected gender norms she is shamed and humiliated because it impacts both her and her family's honor, and perhaps her ability to marry. The causes of gender inequalities are complex, but a number of cultural factors in India can explain how son preference, a key driver of daughter neglect, is so prevalent.[112][115][116]

Patriarchal society

Patriarchy is a social system of privilege in which men are the primary authority figures, occupying roles of political leadership, moral authority, control of property, and authority over women and children. Most of India, with some exceptions, has strong patriarchal and patrilineal customs, where men hold authority over female family members and inherit family property and title. Examples of patriarchy in India include prevailing customs where inheritance passes from father to son, women move in with the husband and his family upon marriage, and marriages include a bride price or dowry. This 'inter-generational contract' provides strong social and economic incentives for raising sons and disincentives for raising daughters.Larsen, Mattias, ed. Vulnerable Daughters in India: Culture, Development and Changing Contexts. Routledge, 2011 (pp. 11–12).</ref> The parents of the woman essentially lose all they have invested in their daughter to her husband's family, which is a disincentive for investing in their girls during youth. Furthermore, sons are expected to support their parents in old age and women have very limited ability to assist their own parents.[117]

Son preference

A key factor driving gender inequality is the preference for sons, as they are deemed more useful than girls. Boys are given the exclusive rights to inherit the family name and properties and they are viewed as additional status for their family. In a survey-based study of 1990s data, scholars[118] found that son are believed to have a higher economic utility as they can provide additional labor in agriculture. Another factor is that of religious practices, which can only be performed by males for their parents' afterlife. All these factors make sons more desirable. Moreover, the prospect of parents 'losing' daughters to the husband's family and the expensive dowry of daughters further discourages parents from having daughters.[118][119] Additionally, sons are often the only person entitled to performing funeral rites for their parents.[120] Thus, a combination of factors has shaped the imbalanced view of sexes in India. A 2005 study in Madurai, India, found that old age security, economic motivation, and to a lesser extent, religious obligations, continuation of the family name, and help in business or farm, were key reasons for son preference. In turn, emotional support and old age security were the main reasons for daughter preference. The study underscored a strong belief that a daughter is a liability.[121]

Discrimination against girls

While women express a strong preference for having at least one son, the evidence of discrimination against girls after they are born is mixed. A study of 1990s survey data by scholars[118] found less evidence of systematic discrimination in feeding practices between young boys and girls, or gender-based nutritional discrimination in India. In impoverished families, these scholars found that daughters face discrimination in the medical treatment of illnesses and in the administration of vaccinations against serious childhood diseases. These practices were a cause of health and survival inequality for girls. While gender discrimination is a universal phenomena in poor nations, a 2005 UN study found that social norms-based gender discrimination leads to gender inequality in India.[122]

Dowry

In India, dowry is the payment in cash or some kind of gifts given to bridegroom's family along with the bride. The practice is widespread across geographic region, class and religions.[123] The dowry system in India contributes to gender inequalities by influencing the perception that girls are a burden on families. Such beliefs limit the resources invested by parents in their girls and limits her bargaining power within the family. Parents save gold for dowry for their daughters since their birth but do not invest so they could earn gold medals.[124]

The payment of a dowry has been prohibited under The 1961 Dowry Prohibition Act in Indian civil law and subsequently by Sections 304B and 498a of the Indian Penal Code (IPC).[125] Despite of the laws dowry abuse and domestic abuse is rising.[126] Several studies show that while attitudes of people are changing about dowry, the institution has changed very little,[127] and prejudices even continues to prevail.[112][128]

Marriage laws

Men and women have equal rights within marriage under Indian law, with the exception of all men who are allowed to unilaterally divorce their wife.[122] The legal minimum age for marriage is 18 for women and 21 for men, except for those Indians whose religion is Islam for whom child marriage remains legal under India's Mohammedan personal laws. Child marriage is one of the detriments to empowerment of women.[122]

Discrimination against men

Some men's advocacy groups have complained that the government discriminates against men through the use of overly aggressive laws designed to protect women.[129] There is no recognition of sexual molestation of men and rarely the police stations lodge a First Information Report (FIR); men are considered the culprit by default even if it was the woman that committed sexual abuse against men. Women can jail husband's family for dowry related cases by just filing an FIR.[130] The men's rights movement claims that the law IPC 498A demands that the husband's family is considered guilty by default, unless proven otherwise, in other words, it implements the doctrine of 'guilty unless proven innocent' defying the universally practiced doctrine of 'innocent until proven guilty'. According to one source, this provision is much abused as only four percent of the cases go to the court and the final conviction rate is as low as two percent.[131][132] The Supreme Court of India has found that women are filing false cases under the law IPC 498A and it is ruining the marriages.[133] Some parents state, "discrimination against girls is no longer rampant and education of their child is really important for them be it a girl or a boy."[134] The Men's rights movement in India call for gender-neutral laws, especially in regards to child custody, divorce, sexual harassment, and adultery laws. Men's rights activists state that husbands don't report being attacked by their wives with household utensils because of their ego.[135] These activist petition that there is no evidence to prove that the domestic violence faced by men is less than that faced by women.[136]

Political and legal reforms

Since its independence, India has made significant strides in addressing gender inequalities, especially in the areas of political participation, education, and legal rights.[16][137] Policies and legal reforms to address gender inequalities have been pursued by the government of India. For instance, the Constitution of India contains a clause guaranteeing the right of equality and freedom from sexual discrimination.[138] India is also signatory to the Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, or CEDAW.[139] However, the government maintains some reservations about interfering in the personal affairs of any community without the community's initiative and consent.[122] A listing of specific reforms is presented below.

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

- Prenatal Diagnostic Testing Ban

- The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013

- Hindu Succession Act, 1956 (Amended in 2005; Gives equal inheritance rights to daughters and sons – applies to Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs)

- Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act of 1937, (The inheritance rights are governed by Sharia and the share of females are less than males as mandated by Quran)[140]

State initiatives to reduce gender inequality

Different states and union territories of India, in cooperation with the central government, have initiated a number of region-specific programs targeted at women to help reduce gender inequality over the 1989-2013 period. Some of these programs include[122] Swarnajayanti Gram Swarozgar Yojana, Sampoorna Gramin Rozgar Yojana, Awareness Generation Projects for Rural and Poor women, Condensed Course of Education for Adult Women, Kishori Shakti Yojana, Swayamsidha Mahila Mandal Programme,[141] Rashtriya Mahila Kosh, Support to Training and Employment Programme for Women, Swawalamban Programme, Swashakti Project, Swayamsidha Scheme, Mahila Samakhya Programme,[142] Integrated Child Development Services, Balika Samriddhi Yojana, National Programme of Nutritional Support to Primary Education (to encourage rural girls to attend primary school daily), National Programme for Education of Girls at Elementary Level, Sarva Shiksha Abyhiyan, Ladli Laxmi Yojana, Delhi Ladli Scheme and others.[122][143]

Bombay High Court, recently in March 2016 has ruled out a judgment that "Married daughters are also obligated to take care of their parents". This is a very bold step towards breaking the traditional norms of the defined roles in society. Also, this shall also motivate women to be more independent not only for themselves but also for their parents.

Organisations

See also

- Female foeticide in India

- Feminism in India

- Gender pay gap in India

- Men's rights movement in India

- National Commission for Women

- Rape in India

- Welfare schemes for women in India

- Women in agriculture in India

- Women in India

- Women in the Indian Armed Forces

- Women's Reservation Bill

- Women's suffrage in India

References

- The Global Gender Gap Report 2013, World Economic Forum, Switzerland

- Dijkstra; Hanmer (2000). "Measuring socio-economic gender inequality: Toward an alternative to the UNDP gender-related development index". Feminist Economics. 6 (2): 41–75. doi:10.1080/13545700050076106. S2CID 154578195.

- Tisdell, Roy; Ghose (2001). "A critical note on UNDP's gender inequality indices". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 31 (3): 385–399. doi:10.1080/00472330180000231. S2CID 154447225.

- "Indian Rape Laws Cannot Be Gender-Neutral, Says Central Government". www.vice.com. 4 July 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- "Activists join chorus against gender-neutral rape laws". The Times of India. 7 March 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- "Gender equality". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- Kundu, Subhash C. (2003). "Workforce diversity status: a study of employees' reactions". Industrial Management & Data Systems. 103 (4): 215–226. doi:10.1108/02635570310470610.

- Pande, Astone (2007). "Explaining son preference in rural India: The independent role of structural versus individual factors". Population Research and Policy Review. 26: 1–29. doi:10.1007/s11113-006-9017-2. S2CID 143798268.

- "Gender Equality in India - Empowering Women, Empowering India". Hindrise. 23 November 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- Spatz, Melissa (1991). "A 'Lesser' Crime: A Comparative Study of Legal Defenses for Men Who Kill Their Wives". Colum. J. L. & Soc. Probs. 24: 597, 612.

- Citation is 30 years old

- Gender Statistics The World Bank (2012)

- Global average data not available

- "Global Gender Gap Report 2013". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- 2011 Gender Gap Report World Economic Forum, page 9

- "Social Institutions and Gender Index: India Profile". OECD. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Klasen; Schüler (2011). "Reforming the gender-related development index and the gender empowerment measure: Implementing some specific proposals". Feminist Economics. 17 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1080/13545701.2010.541860. S2CID 154373171.

- Klasen (2006). "UNDP's gender‐related measures: some conceptual problems and possible solutions". Journal of Human Development. 7 (2): 243–274. doi:10.1080/14649880600768595. S2CID 15421076.

- Robeyns (2003). "Sen's capability approach and gender inequality: selecting relevant capabilities". Feminist Economics. 9 (2–3): 61–92. doi:10.1080/1354570022000078024. S2CID 15946768.

- Arora (2012). "Gender inequality, economic development, and globalization: A state level analysis of India". The Journal of Developing Areas. 46 (1): 147–164. doi:10.1353/jda.2012.0019. hdl:10072/46916. S2CID 54755937.

- Bhattacharya (2013). "Gender inequality and the sex ratio in three emerging economies" (PDF). Progress in Development Studies. 13 (2): 117–133. doi:10.1177/1464993412466505. hdl:10943/662. S2CID 40055721.

- "The EU's Contribution A to Women's Rights and Women's Inclusion: Aspects of Democracy Building in South Asia, with special reference to India" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- "India's unwanted girls". BBC News. 23 May 2011.

- "The India Gender Gap Review" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- "Census of India 2011: Child sex ratio drops to lowest since Independence". The Times of India. 31 March 2011.

- "Why do educate and well-off Indians kill their girl children?". Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "Literacy in India". Census2011.co.in. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- "Women's Education in India" (PDF). Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- Khan, Sadia; Hasan, Ziya (November 2020). "Tribal Women in India: The Gender Inequalities and its Repercussions". ResearchGate.

- "Socio-Economic Status of Tribal Women of Jharkhand". Docslib. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- "Working women face longer days for lower pay". Wageindicator.org. 29 May 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- "Chronic Hunger and the Status of Women in India". Thp.org. Archived from the original on 10 January 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- "Human Development Report for 2012". United Nations Development Project. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Lockwood, Nancy (2009). "Perspectives on Women in Management in India" (PDF). Society for Human Resource Management.

- Rao, E. Krishna (2006), "Role of Women in Agriculture: A Micro Level Study." Journal of Global Economy, Vol 2

- Roopam Singh and Ranja Sengupta, EU FTA and the Likely Impact on Indian Women Executive Summary Centre for Trade and Development and Heinrich Boell Foundation (2009)

- Wage Rates in Rural India (2008-09) Archived 18 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Labour Bureau, MINISTRY OF LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT, Govt of India (2010)

- Wichterich, Christa (2012). "The Other Financial Crisis: Growth and crash of the microfinance sector in India". Development. 55 (3): 406–412. doi:10.1057/dev.2012.58. S2CID 84343066.

- Biswas, Soutik. "India's micro-finance suicide epidemic." BBC News 16 (2010).

- "Home". Investment Gaps. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- "Periodic Review: India report 2005" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Deo, Shipra; Roush, Tyler (16 August 2021). "'This is not your home' – Revealing a brutal system of oppression and gender discrimination among India's Scheduled Tribes". Landesa. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- Sethi, Harsh (31 May 1992). "Tribal women edged out of forests". www.downtoearth.org.in. Down to Earth. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- Sharma, Kriti (23 November 2018). "Mapping Violence in the Lives of Adivasi Women: A Study from Jharkhand". Economic & Political Weekly. 53 (42). Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- Rao, S. T.; Rao, G. T.; Ganesh, M. S. "Women entrepreneurship in India (a case study in Andhra Pradesh)". The Journal of Commerce. 3: 43–49.

- Williams, C. C.; Gurtoo, A. (2011). "Women entrepreneurs in the Indian informal sector: marginalisation dynamics or institutional rational choice?". International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship. 3: 6–22. doi:10.1108/17566261111114953. S2CID 145216551.

- Chudgar, A.; Sankar, V. (2008). "The relationship between teacher gender and student achievement: Evidence from five Indian states". Compare. 38 (5): 627–642. doi:10.1080/03057920802351465. S2CID 143441023.

- Gupta, N.; Sharma, A. K. (2003). "Gender inequality in the work environment at institutes of higher learning in science and technology in India". Work, Employment and Society. 17 (4): 597–616. doi:10.1177/0950017003174001. S2CID 143255925.

- Gupta, N. (2007). "Indian women in doctoral education in science and engineering: A study of informal milieu at the reputed Indian institutes of technology". Science, Technology, & Human Values. 32 (5): 507–533. doi:10.1177/0895904805303200. S2CID 145486711.

- "No permanent commission for women in forces: Antony". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012.

- "Women Army Officers Can Get Command Roles. Top Court Slams "Stereotypes"".

- "Justifying Sexism, Centre Says Women Can't Be Given Command Posts as Army Men Won't Accept It".

- "Eight Women Fighter Pilots in Indian Air Force as on July 1: Govt". 26 July 2019.

- "Army opens 'risky' roles for women but Indian Navy won't have women sailors anytime soon".

- "Gender Equality and Empowerment - UN India". Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- Unterhalther, E. (2006). Measuring Gender Inequality in South Asia. London: The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF).

- Victoria A. Velkoff (October 1998). "Women of the World: Women's Education in India" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- Kelly, O (2014). "Beyond the education silo? Tackling adolescent secondary education in rural India". British Journal of Sociology of Education. 35 (5): 731–752. doi:10.1080/01425692.2014.919843. S2CID 144694961.

- Kugler, A. D.; Kumar, S (2017). "Preference for Boys, Family Size, and Educational Attainment in India". Demography. 54 (3): 835–859. doi:10.1007/s13524-017-0575-1. PMC 5486858. PMID 28484996.

- Muralidharan, K.; Prakash, N. (2017). "Cycling to school: increasing secondary school enrollment for girls in India". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 9 (3): 321–350. doi:10.1257/app.20160004.

- Siddhu, Gaurav (2011). "Who makes it to secondary school? Determinants of transition to secondary schools in rural India". International Journal of Educational Development. 31 (4): 394–401. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.01.008.

- Sahni, Rohini; Shankar, V. Kalyan (1 February 2012). "Girls' higher education in India on the road to inclusiveness: on track but heading where?". Higher Education. 63 (2): 237–256. doi:10.1007/s10734-011-9436-9. ISSN 0018-1560. S2CID 145692708.

- Upadhyay, Sugeeta (2007). "Wastage in Indian higher education". Economic and Political Weekly.

- Kalyani Menon-Sen, A. K. Shiva Kumar (2001). "Women in India: How Free? How Equal?". United Nations. Archived from the original on 11 September 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- "Millennium Development Goals: India Country report 2011" (PDF). Central Statistical Organisation, Government of India.

- Kingdon, Geeta Gandhi. "The progress of school education in India." Oxford Review of Economic Policy 23.2 (2007): 168-195.

- "Men without women". The Hindu. 31 August 2003. Archived from the original on 21 March 2004. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- Charu Sudan Kasturi. "PM vetoes women's IIT". The Telegraph. Calcutta (Kolkata). Archived from the original on 13 September 2012.

- Gender Gap Report World Economic Forum (2011), page 4

- Age Data C13 Table (India/States/UTs ) Final Population - 2011 Census of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India (2013)

- Gender and cooperative conflicts (chapter 8) Amartya Sen

- T.V. Sekher and Neelambar Hatti, Discrimination of Female Children in Modern India: from Conception through Childhood

- Patnaik, Priti (25 May 2011). "India's census reveals a glaring gap: girls | Priti Patnaik". the Guardian. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- MacPherson, Yvonne (November 2007). "Images and Icons: Harnessing the Power of Media to Reduce Sex-Selective Abortion in India". Gender and Development. 15 (2): 413–23. doi:10.1080/13552070701630574.

- "Abortion: Female infanticide". BBC.

- Sharma, R. (2008). Concise Textbook Of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology 2/e. New Delhi: Elsevier

- "Girl child day on January 24". The Times of India. 19 January 2009. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012.

- National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3): 2005-2006 Government of India (2005)

- Suicides in India Archived 13 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine The Registrar General of India, Government of India (2012)

- Udry, J. Richard (November 1994). "The Nature of Gender". Demography. 31 (4): 561–573. doi:10.2307/2061790. JSTOR 2061790. PMID 7890091. S2CID 38476067.

- Vijaykumar L. (2007), Suicide and its prevention: The urgent need in India, Indian J Psychiatry;49:81-84,

- Polgreen, Lydia (30 March 2010). "Suicides, Some for Separatist Cause, Jolt India". The New York Times.

- Maselko, J; Parel, Vikram (2008). "Why women attempt suicide: the role of mental illness and social disadvantage in a community cohort study in India". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 62 (9): 817–822. doi:10.1136/jech.2007.069351. PMID 18701733. S2CID 12589827.

- Vindhya, U. (2016). "Quality of Women's Lives in India: Some Findings from Two Decades of Psychological Research on Gender". Feminism & Psychology. 17 (3): 337–356. doi:10.1177/0959353507079088. S2CID 145551507.

- Basu, S (2012). "Mental health concerns for Indian women". Indian Journal of Gender Studies. 19: 127–136. doi:10.1177/097152151101900106. S2CID 57639166.

- Vindhya, U.; Kiranmayi, A.; Vijayalakshmi, V. (2001). "Women in Psychological Distress: Evidence from a Hospital-Based Study". Economic and Political Weekly. 36 (43): 4081–4087. JSTOR 4411294.

- Patel, Vikram; Kirkwood, Betty R.; Pednekar, Sulochana; Pereira, Bernadette; Barros, Preetam; Fernandes, Janice; Datta, Jane; Pai, Reshma; Weiss, Helen (1 April 2006). "Gender Disadvantage and Reproductive Health Risk Factors for Common Mental Disorders in Women". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (4): 404–13. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.404. ISSN 0003-990X. PMID 16585469.

- Crime in India 2012 Statistics Archived 20 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt of India, Table 5.1

- "National Family Health Survey-3". Macro International.

- "Login".

- NCRB, Crime against women Archived 16 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Chapter 5, Annual NRCB Report, Government of India (2013)

- Kalokhe, Ameeta; del Rio, Carlos; Dunkle, Kristin; Stephenson, Rob; Metheny, Nicholas; Paranjape, Anuradha; Sahay, Seema (3 April 2017). "Domestic violence against women in India: A systematic review of a decade of quantitative studies". Global Public Health. 12 (4): 498–513. doi:10.1080/17441692.2015.1119293. ISSN 1744-1692. PMC 4988937. PMID 26886155.

- Kaur, Ravneet; Garg, Suneela (April 2010). "Domestic Violence Against Women: A Qualitative Study in a Rural Community". Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health. 22 (2): 242–251. doi:10.1177/1010539509343949. ISSN 1010-5395. PMID 19703815. S2CID 3022707.

- National Crimes Record Bureau, Crime in India 2012 - Statistics Archived 20 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine Government of India (May 2013)

- Sirnate, Vasundhara (1 February 2014). "Good laws, bad implementation". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- Schmalleger, John Humphrey, Frank (29 March 2011). Deviant behavior (2nd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 252. ISBN 978-0763797737.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The Irrationality of Rationing (25 January 2013). "Lies, Damned Lies, Rape, and Statistics". Messy Matters. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- "Court sentences 4 men to death in New Delhi gang rape case". CNN. 14 September 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- S. Harrendorf, M. Heiskanen, S. Malby, International Statistic on Crime and Justice United Nations Office on Drugs & Crime (2012)

- "The rapes that India forgot". BBC News. 5 January 2013.

- Mandhana, Niharika; Trivedi, Anjani (18 December 2012). "Indians Outraged Over Rape on Moving Bus in New Delhi". India Ink.

- "Rising number of dowry deaths in India: NCRB". The Hindu. 7 August 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- United States Department of State|title=US Department of State, India Country Report on Human Rights Practices, 2011

- "Toward Gender Equality in Rural India", Gender Equality and Inequality in Rural India, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, doi:10.1057/9781137373922.0013, ISBN 9781137373922, retrieved 10 April 2023

- The Global Gender Gap Report 2012, World Economic Forum, Switzerland, page 4

- The Global Gender Gap Report 2013, World Economic Forum, Switzerland, Table 3b and 5, page 13 and 19

- The Global Gender Gap Report 2012, World Economic Forum, Switzerland, page 16

- State-Wise Voter Turnout in General Elections 2014 Government of India (2014)

- Political Reservations and Women's Entrepreneurship in India Ghani et al. (2014), World Bank and Harvard University/NBER, pages 6, 29

- Lorber, J. (1994). Paradoxes of Gender. Yale University Press, page 2-6, 126-143, 285-290

- Sen, Amartya (2001). "Many Faces of Gender Inequality". Frontline, India's National Magazine. 18 (22): 1–17.

- Sekher, TV; Hattie, Neelambar (2010). Unwanted Daughters: Gender discrimination in Modern India. Rawat Publications.

- "India - Restoring the Sex-ratio Balance". UNDP. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony. 2010. "Wars Against Women," in The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., Chapter 4, pp. 137–72.

- Gupta, Monica Das (1987). "Selective discrimination against female children in rural Punjab, India". Population and Development Review. 1987 (1): 77–100. doi:10.2307/1972121. JSTOR 1972121. S2CID 30654533.

- Kabeer, Naila (1996). "Agency, Well‐being & Inequality: Reflections on the Gender Dimensions of Poverty". IDS Bulletin (Submitted manuscript). 27 (1): 11–21. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.1996.mp27001002.x.

- Larsen, Mattias, Neelambar Hatti, and Pernille Gooch. "Intergenerational Interests, Uncertainty and Discrimination." (2006).

- Rangamuthia Mutharayappa, M. K. (1997). Son Preference and Its Effect on Fertility in India. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences.

- Muthulakshmi, R. (1997). Female infanticide, its causes and solutions. New Delhi: Discovery Publishing House.

- Sekher and Hatti, 2007 Unwanted Daughters: Gender discrimination in modern India pp. 3-4.

- Begum and Singh; CH 7 Sekher and Hatti, 2007 Unwanted Daughters: Gender discrimination in modern India 7

- "Periodic Review: India report 2005" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Babu; Babu (2011). "Dowry deaths: a neglected public health issue in India". Int. Health. 3 (1): 35–43. doi:10.1016/j.inhe.2010.12.002. PMID 24038048.

- Nigam, Shalu (9 July 2021). Domestic Violence Law in India Myth and Misogyny. Routledge. ISBN 9780367344818. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- "The Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961". Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- Nigam, Shalu (29 September 2019). Women and Domestic Violence Law in India A Quest for Justice. Routledge. ISBN 9780367777715.

- Nigam, Shalu (9 July 2021). Domestic Violence Law in India Myth and Misogyny. Routledge. ISBN 9780367344818.

- Srinivasan, Padma; Lee, Gary R. (2004). "The dowry system in Northern India: Women's attitudes and social change". Journal of Marriage and Family. 66 (5): 1108–1117. doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00081.x.

- pro-women laws being misused

- Chandrashekhar, Dr Mamta (2016). "Human Rights, Women and Violation". Sex Ratio.

- "Are India's anti-dowry laws a trap for urban males?". 5 September 2008. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008.

- "Sex after false promise of marriage is rape: Court".

- "Supreme Court: False cruelty cases under Section 498A ruining marriages". The Times of India. 9 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- Girls gain extra points in admissions

- "Nagging wife? Help is at hand!". The Indian Express. Press Trust of India. 11 November 2005. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- "Now, men seek cover under domestic violence law". DNA India. 10 June 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- "Report on the State of Women: India" (PDF). Center for Asia-Pacific Women in Politics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Report on the State of Women Archived 6 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Convention for the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination Against Women". United Nations. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- Inheritance and Succession, Rights of Women and Daughters under Personal Laws Javed Razack, Lex Orates, Indian Law

- Promotion and Strengthening of Mahila Mandals Archived 23 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Govt of Haryana

- Mahila Samakhya UNICEF India

- Delhi Ladli Scheme 2008 Archived 8 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine Government of Delhi