Shaykh al-Islām

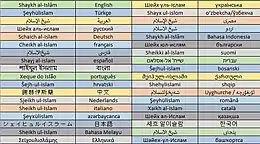

Shaykh al-Islām (Arabic: شيخ الإسلام, romanized: Šayḫ al-Islām; Persian: شِیخُالاسلام, Sheykh-ol-Eslām; Urdu: شِیخُالاسلام, Sheykh-ul-Islām; Ottoman Turkish: شیخ الاسلام, Turkish: Şeyhülislam[1]) was used in the classical era as an honorific title for outstanding scholars of the Islamic sciences.[2]: 399 [3] It first emerged in Khurasan towards the end of the 4th Islamic century.[2]: 399 In the central and western lands of Islam, it was an informal title given to jurists whose fatwas were particularly influential, while in the east it came to be conferred by rulers to ulama who played various official roles but were not generally muftis. Sometimes, as in the case of Ibn Taymiyyah, the use of the title was subject to controversy. In the Ottoman Empire, starting from the early modern era, the title came to designate the chief mufti, who oversaw a hierarchy of state-appointed ulama. The Ottoman Sheikh al-Islam (French spelling: cheikh-ul-islam[note 1]) performed a number of functions, including advising the sultan on religious matters, legitimizing government policies, and appointing judges.[2]: 400 [5]

| Part of a series on Islam |

| Usul al-Fiqh |

|---|

| Fiqh |

| Ahkam |

| Legal vocations and titles |

|

With the abolition of the Caliphate in 1924, the official Ottoman office of Shaykh al-Islām, already in decline, was eliminated.[6] Modern times have seen the role of chief mufti carried out by grand muftis appointed or elected in a variety of ways.[3]

Classical usage

Like other honorific titles starting with the word sheikh, the term shaykh al-islam was in the classical era reserved for ulama and mystics. It first appeared in Khurasan in the 4th century AH (10th century AD).[2]: 399 In major cities of Khurasan it seems to have had more specific connotations, since only one person held the title at any given time and place. Holders of the title in Khurasan were among the most influential ulama, but there is no evidence that they delivered fatwas.

Under the Ilkhans, the Delhi Sultanate and the Timurids the title was conferred, often by the ruler, to high-ranking ulama who performed various functions but were not generally muftis.[2]: 400

In the Kashmiri Sultanate, it was implemented during the reign of Sultan Sikandar. He established the office of the Shaikhu'l-Islam under the influence of Sayyid Muhammad Hamadan, who had come to Kashmir in 1393 AD.[7]

In Syria and Egypt, it was given to influential jurists and had an honorific rather than an official role. By 700 AH/1300 AD in the central and western lands of Islam, the term became associated with giving of fatwas.

Ibn Taymiyya was given the title by his supporters but his adversaries contested this use.[2]: 400 For example, the Hanafi scholar 'Ala' al-Din al-Bukhari issued a fatwa stating that anyone who called Ibn Taymiyya "Shaykh al-islam" had committed disbelief (kufr).[8][9] However, Shafiite scholar Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani defended the title of Shaykh al Islam for Ibn Taymiyyah, saying in his own words, " His status as imam, sheikh, Taqiyuddin Ibn Taimiyah, is brighter than the sun. And his title with Shaykhul Islam, we still often hear from holy orals until now, and will continue to survive tomorrow.."[10][11], which was recorded by his student al Sakhawi.[11] The Hanbalite madhhab scholar and follower of Ibn Taymiyyah, Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (himself also given Shaykh al Islam title by his contemporary) defended the usage of the title for him. Ibn Taymiyya and Ibn Qayyim are both known for contradicting the views of the majority of scholars of all four schools of thought (Hanafi, Shafi'i, Maliki, and Hanbali) of their time in Damascus and of later periods.[12][13]

There is disagreement on whether the title was honorific or represented a local mufti in Seljuq and early Ottoman Anatolia.[2]: 400

In the Ottoman Empire

In the Ottoman Empire, which controlled much of the Sunni Islamic world from the 14th to the 20th centuries, the Grand Mufti was given the title Sheikh ul-islam (Ottoman Turkish: Şeyḫülislām). The Ottomans had a strict hierarchy of ulama, with the Sheikh ul-Islam holding the highest rank. A Sheikh ul-Islam was chosen by a royal warrant amongst the qadis of important cities. The Sheikh ul-Islam had the power to confirm new sultans. However, once the sultan was affirmed, the sultan retained a higher authority than the Sheik ul-Islam. The Sheikh ul-Islam issued fatwas, which were written interpretations of the Quran that had authority over the community. The Sheikh ul-Islam represented the Sacred Law of Shariah and in the 16th century its importance rose which led to increased power. Sultan Murad IV appointed a Sufi, Zakeriyazade Yahya Efendi, as his Sheikh ul-Islam during this time which led to violent disapproval. The objection to this appointment made obvious the amount of power the Sheikh ul-Islam had, since people were worried he would alter the traditions and norms they were living under by issuing new fatwas.

The office of Sheikh ul-islam was abolished in 1924, at the same time as the Ottoman Caliphate. After the National Assembly of Turkey was established in 1920, the office of Sheikh ul-Islam was placed in the Shar’iyya wa Awqaf Ministry. In 1924, the office of Sheikh ul-Islam was abolished along with the Caliphate. The office was replaced by the Presidency of Religious Affairs.[14] As the successor entity to the office of the Sheikh ul-Islam, the Presidency of Religious Affairs is the most authoritative entity in Turkey in relation to Sunni Islam.[14]

Honorific recipients

The following Islamic scholars have been given the honorific title "Shaykh al-Islam":

- Abu Mansur al-Maturidi[15] (b. 231 AH)

- Al-Daraqutni[16] (b. 306 AH)

- Abu Uthman al-Sabuni (b. 373 AH)[17]

- Al-Bayhaqi (b. 384 AH)[18]

- Abu Ishaq al-Shirazi (b. 393 AH)

- Abu Talib al-Makki[19] (b. 386 AH)

- Najm al-Din 'Umar al-Nasafi (b. 461 AH)[20][21]

- Khwaja Abdullah Ansari[2]: 400 (b. 481 AH)

- Al-Juwayni[22] (b. 419 AH)

- Fakhr al-Din al-Razi[23] (b. 544 AH)

- Ibn al-Jawzi (b. 509 or 510 AH)

- Burhan al-Din al-Marghinani (b. 530 AH)[24]

- Al-'Izz ibn 'Abd al-Salam[25][26] (b. 577 AH)

- Al-Mundhiri (b. 581 AH)[27]

- Ibn Daqiq al-'Id[28] (b. 625 AH)

- Al-Nawawi[29] (b. 631 AH)

- Ibn Taymiyyah[30][2] (b. 661 AH)

- Taqi al-Din al-Subki[31] (b. 683 AH)

- Ibn al-Mulaqqin[32] (b. 723 AH)

- Siraj al-Din al-Bulqini[33][34] (b. 724 AH)

- Zain al-Din al-'Iraqi[35] (b. 725 AH)

- Taj al-Din al-Subki[36] (b. 727 AH)

- Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani[37] (b. 773 AH)

- Al-Kamal ibn al-Humam[38](b. 790 AH)

- Sharaf al-Din al-Munawi[39] (b. 798 AH)

- Kamal al-Din ibn Abi Sharif[40] (b. 822 AH)

- Zakariyya al-Ansari[41][42][43][44] (b. 823 AH)

- Al-Suyuti[45][46] (b. 849 AH)

- Ibn Kemal[47] (b. 873 AH)

- Shihab al-Din al-Ramli[48]

- Ebussuud Efendi[49] (b. 896 AH)

- Ibn Hajar al-Haytami[50] (b. 909 AH)

- Shams al-Din al-Ramli[51] (b. 919 AH)

- Ahmad Zayni Dahlan[52] (b. 1231 or 1232 AH)

- Hussain Ahmed Madani[53][54] (b. 1296 AH)

- Muhammad al-Tahir ibn 'Ashur (b. 1296 AH)

- Baha'i Mehmed Efendi (b. 1595-6[55])

- Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri (b. 1951 CE or 1370 AH)

See also

- Category:Shaykh al-Islams of the Religious Council of the Caucasus

- Category:Sheikh-ul-Islams of the Ottoman Empire

- Allamah

- Mufti

- Sheikh

- Sheikh (Sufism)

- Mawlānā

- Hadrat

- Grand Mufti

- Hujjat al-Islam

- Seghatoleslam

References

- Hogarth, D. G. (January 1906). "Reviewed Work: Corps de Droit Ottoman by George Young". The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 21 (81): 186–189. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXI.LXXXI.186. JSTOR 549456. - CITED: p. 189: "'Sheikh-ul-Islam,' for instance, should be written 'Sheiklı ul-Islam,' and so forth. This mistake is common, but none the less a mistake." - Review of Corps de Droit Ottoman

- J.H. Kramers-[R.W. Bulliet] & R.C. Repp (1997). "Skaykh al-Islam". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume IX: San–Sze (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Gerhard Böwering, Patricia Crone, Mahan Mirza, The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought, p 509-510. ISBN 0691134847

- Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Würzburg. pp. 21–51.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (info page on book at Martin Luther University) - Cited: p. 40 (PDF p. 42) - James Broucek (2013). "Mufti/Grand mufti". In Gerhard Böwering; Patricia Crone (eds.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press.

- Brockett, Adrian Alan, Studies in two transmissions of the Qur'an

- Hasan, Mohibbul (2005). Kashmīr under the sultāns. Delhi: Aakar Books. ISBN 81-87879-49-1. OCLC 71835146.

- Correct Islamic Doctrine/Islamic Doctrine by Ibn Khafif

- The Biographies Of The Elite Lives Of The Scholars, Imams & Hadith Masters by Gibril Fouad Haddad

- Baits, Ammi Nur. "Gelar Syaikhul Islam untuk Ibnu Taimiyah". Konsultasi Syariah. Dewan Pembina Konsultasisyariah.com. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- Sakhawi, Shams al Din (1999). "كتاب الجواهر والدرر في ترجمة شيخ الإسلام ابن حجر". al maktabat al shaamilat al haditha. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- Holtzman, Livnat (January 2009). "Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya". Essays in Arabic Literary Biography: 211.

- Bori, Caterina; Holtzman, Livnat (January 2010). "A Scholar in the Shadow". Oriente Moderno: 19.

- Establishment and a Brief History, Presidency of Religious Affairs

- Gibril Fouad Haddad (2015). The Biographies of the Elite Lives of the Scholars, Imams and Hadith Masters. Zulfiqar Ayub. p. 141.

- Lucas, Scott C. (2004). Constructive Critics, Ḥadīth Literature, and the Articulation of Sunnī Islam The Legacy of the Generation of Ibn Saʻd, Ibn Maʻīn, and Ibn Ḥanbal. Brill. p. 368. ISBN 9789004133198.

- Izz al-Din ibn 'Abd al-Salam (1999). The Belief of the People of Truth. Translated by Gibril Fouad Haddad. As-Sunnah Foundation of America. p. 57. ISBN 9781930409026.

- Encyclopedia of Sahih Al-Bukhari By Abu-`Abdullah Muhammad-Bin-Isma`il Al-Bukhari

- Yazaki, Saeko (2012). Islamic Mysticism and Abu Talib Al-Makki: The Role of the Heart. Routledge. p. 122. ISBN 978-0415671101.

- Kamal al-Din ibn Abi Sharif (2017). Muhammad al-'Azazi (ed.). الفرائد في حل شرح العقائد وهو حاشية ابن أبي شريف على شرح العقائد للتفتازاني (in Arabic). Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Kotob al-'Ilmiyya. p. 19. ISBN 9782745189509.

- Khalid al-Baghdadi (2021). حاشية مولانا خالد النقشبندي على السيالكوتي على الخيالي على شرح التفتازاني على العقائد النسفية (in Arabic). Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Kotob al-'Ilmiyya. p. 4. ISBN 9782745190345.

- M. M. Sharif, A History of Muslim Philosophy, 1.242. ISBN 9694073405

- Islam and Other Religions: Pathways to Dialogue by Irfan Omar

- Mona Siddiqui (2012). The Good Muslim: Reflections on Classical Islamic Law and Theology. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780521518642.

The Hidaya is a classic book of Islamic jurisprudence by Sheikh al-Islam Burhan al-Din 'Ali b. Abu Bakr al-Marghinani (d. 1197).

- Jackson, Sherman (1996). Islamic Law and the State: The Constitutional Jurisprudence of Shihab Al-Din Al-Qarafi (Studies in Islamic Law & Society). Brill. p. 10. ISBN 9004104585.

- Allah's Names and Attributes (Islamic Doctrines & Beliefs) by Imam Al-Bayhaqi (Author), Gibril Fouad Haddad (Translator)

- مغلوث، سامي بن عبد الله (31 December 2018). أطلس أعلام المحدثين (Atlas of Hadith Scholars). al-ʿUbaikān li-n-Našr. p. 314. ISBN 9786035091886.

- Islamic Culture - Volume 45 - Page 195

- Correct Islamic Doctrine/Islamic Doctrine - Page 11.

- Ibn Taymīyah, Aḥmad ibn ʻAbd al-Ḥalīm; Al-Ani, Salman Hassan; Ahmad Tel, Shadia (2009). Kitab Al-Iman Book of Faith. Islamic Book Trust. p. 3, Quoting al uqud al durriyah min manaqib shaykh al islam ibn Taymiyyah. ISBN 9789675062292. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- Mohammad Hassan Khalil, Islam and the Fate of Others: The Salvation Question, Oxford University Press, 3 May 2012, p 89. ISBN 0199796661

- Ayub, Zulfiqar (2 May 2015). THE BIOGRAPHIES OF THE ELITE LIVES OF THE SCHOLARS, IMAMS & HADITH MASTERS Biographies of The Imams & Scholars. Zulfiqar Ayub Publications. p. 291.

- The Middle East Documentation Center (MEDOC) At The University Of Chicago (2002). "knowledge.uchicago.edu". Mamlūk Studies Review Vol. VI (2002). 6: 118. doi:10.6082/M1XP7300.

- The Biographies Of The Elite Lives Of The Scholars, Imams & Hadith Masters by Gibril Fouad Haddad.

- Al-Bayhaqi (1999). Allah's Names and Attributes. Vol. 4 of Islamic Doctrines & Beliefs. Translated by Gibril Fouad Haddad. Islamic Supreme Council of America. p. 113. ISBN 9781930409033.

- Tasawwuf al-Subki

- Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch., eds. (1960). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume I: A–B (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 791. OCLC 495469456.

- "The Biography of Imam al-Kamal ibn al-Humam". Dar al-Ifta' al-Misriyya.

- THE BIOGRAPHIES OF THE ELITE LIVES OF THE SCHOLARS, IMAMS & HADITH MASTERS Biographies of The Imams & Scholars page 281

- Ibn al-Imad al-Hanbali (2012). مصطفى عبد القادر عطا (ed.). شذرات الذهب في أخبار من ذهب [Particles of Gold in Chronicles on Those Who Passed Away] (in Arabic). Vol. 8. Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Kotob al-'Ilmiyya. p. 62.

- Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P., eds. (2002). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume XI: W–Z (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 406. ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Safinah Safinat al-Naja' - The Ship of Salvation

- Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John O. Hunwick

- The Archetypal Sunni Scholar: Law, Theology, and Mysticism in the Synthesis of Al-Bajuri by Aaron Spevack

- Ghersetti, Antonella (18 October 2016). Al-Suyūṭī, a Polymath of the Mamlūk Period Proceedings of the Themed Day of the First Conference of the School of Mamlūk Studies (Ca' Foscari University, Venice, June 23, 2014). Brill. p. 259. ISBN 9789004334526.

- Sayyid Rami Al Rifai (3 July 2015). The Islamic Journal From Islamic Civilisation To The Heart Of Islam, Ihsan, Human Perfection. Sunnah Muakada. p. 37.

- Oliver Leaman, ed. (2015). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Islamic Philosophy. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 198. ISBN 9781472569455.

IBN KEMAL (873–940/1468–1534) The famous shaykh al-Islam of the Ottoman Empire and one of the most prolific writers of Ottoman intellectual history, Shams al-Din Ahmad b. Sulayman b. Kamal Pasha, known more commonly as Ibn Kemal

- IslamKotob (January 1995). "The chosen guard from the flags of the centuries - المختار المصون من أعلام القرون)". p. 72.

- Oliver Leaman, ed. (2015). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Islamic Philosophy. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 9781472569455.

- The Prophets in Barzakh/The Hadith of Isra' and Mi'raj/The Immense Merrits of Al-Sham/The Vision of Allah by Al-Sayyid Muhammad Ibn 'Alawi

- IslamKotob. "The softness of summer and the harvest of fruits from the biographies of notables of the first class of the eleventh century 2 - لطف السمر و قطف الثمر من تراجم أعيان الطبقة الأولى من القرن الحادي عشر 2)". p. 78.

- Muhammad Hisham Kabbani (2004). The Naqshbandi Sufi Tradition Guidebook of Daily Practices and Devotions. Islamic Supreme Council of America. p. 187. ISBN 9781930409224.

- Metcalf, Barbara D. "Husain Ahmad Madani, Maulana". Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- Syeda, Lubna Shireen (2014-08-10). "A study of jamiat-ulama-i-hind with special reference to maulana hussain ahmad madani in freedom movement (A.D. 1919-A.D.1947)". Ambedkar University.

- Lewis 1986, p. 915.

.svg.png.webp)