Chinese zodiac

The Chinese zodiac is a traditional classification scheme based on the Chinese calendar that assigns an animal and its reputed attributes to each year in a repeating twelve-year cycle. Originating from China, the zodiac and its variations remain popular in many East Asian and Southeast Asian countries, such as Japan,[1] South Korea,[2] Vietnam,[2] Singapore, Nepal, Bhutan, Cambodia, and Thailand.[3]

| Chinese zodiac | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 生肖 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | shēngxiào | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 属相 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 屬相 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | shǔxiàng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Identifying this scheme using the generic term "zodiac" reflects several superficial similarities to the Western zodiac: both have time cycles divided into twelve parts, each label at least the majority of those parts with names of animals, and each is widely associated with a culture of ascribing a person's personality or events in their life to the supposed influence of the person's particular relationship to the cycle.

The animals of the Chinese zodiac are not associated with constellations spanned by the ecliptic plane. The Chinese twelve-part cycle corresponds to years, rather than months. The Chinese zodiac is represented by twelve animals, whereas some of the signs in the Western zodiac are not animals, despite the implication of the etymology of the English word zodiac, which derives from zōdiacus, the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek zōdiakòs kýklos (ζῳδιακὸς κύκλος), meaning "cycle of animals".

Signs

The zodiac traditionally begins with the sign of the Rat. The following are the twelve zodiac signs in order, each with its associated characteristics (Heavenly Stems, Earthly Branch, yin/yang force, Trine, and nature element).[4]

| Number | Animal | Characters | Yin/yang | Trine | Fixed element |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rat | 鼠, shǔ (子) | Yang | 1st | Water |

| 2 | Ox | 牛, niú (丑) | Yin | 2nd | Earth |

| 3 | Tiger | 虎, hǔ (寅) | Yang | 3rd | Wood |

| 4 | Rabbit | 兔, tù (卯) | Yin | 4th | Wood |

| 5 | Dragon | 龙/龍, lóng (辰) | Yang | 1st | Earth |

| 6 | Snake | 蛇, shé (巳) | Yin | 2nd | Fire |

| 7 | Horse | 马/馬, mǎ (午) | Yang | 3rd | Fire |

| 8 | Goat | 羊, yáng (未) | Yin | 4th | Earth |

| 9 | Monkey | 猴, hóu (申) | Yang | 1st | Metal |

| 10 | Rooster | 鸡/雞, jī (酉) | Yin | 2nd | Metal |

| 11 | Dog | 狗, gǒu (戌) | Yang | 3rd | Earth |

| 12 | Pig | 猪/豬, zhū (亥) | Yin | 4th | Water |

In Chinese astrology the animal signs assigned by year represent how others perceive one or how one presents oneself. It is a common misconception that the animals assigned by year are the only signs, and many Western descriptions of Chinese astrology draw solely on this system. In fact, there are also animal signs assigned by month (called "inner animals"), by day (called "true animals") and hours (called "secret animals"). The Earth is all twelve signs, with five seasons.

Michel Ferlus (2013) notes that the Old Chinese names of the earthly branches are of Austroasiatic origin.[5] Some of Ferlus' comparisons are given below, with Old Chinese reconstructions cited from Baxter & Sagart (2014).[6]

- 丑: Old Chinese *[n̥]ruʔ (compare Proto-Viet-Muong *c.luː 'water buffalo')

- 午: Old Chinese *[m].qʰˤaʔ (compare Proto-Viet-Muong *m.ŋəːˀ)

- 亥: Old Chinese *[g]ˤəʔ (compare Northern Proto-Viet-Muong *kuːrˀ)

There is also a lexical correspondence with Austronesian:[5]

- 未: Old Chinese *m[ə]t-s (compare Atayal miːts)

The terms for the earthly branches are attested from Shang Dynasty inscriptions and were likely also used before Shang times. Ferlus (2013) suggests that the terms may have been ancient pre-Shang borrowings from Austroasiatic languages that were spoken in the Yangtze River region.[5]

Chinese calendar

Years

Within the Four Pillars, the year is the pillar representing information about the person's family background and society or relationship with their grandparents. The person's age can also be easily deduced from their sign, the current sign of the year, and the person's generational disposition (teens, mid-20s, and so on). For example, a person born a Tiger is 12, 24, 36, (etc.) years old in the year of the Tiger (2022); in the year of the Rabbit (2023), that person is one year older.

The following table shows the 60-year cycle matched up to the Gregorian calendar for the years 1924–2043. The sexagenary cycle begins at lichun about February 4 according to some astrological sources.[7][8]

| Year | Year | Associated element | Heavenly stem | Earthly branch | Associated animal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1924–1983 | 1984–2043 | |||||

| 1 | Feb 05 1924–Jan 23 1925 | Feb 02 1984–Feb 19 1985 | Yang Wood | 甲 | 子 | Rat |

| 2 | Jan 24 1925–Feb 12 1926 | Feb 20 1985–Feb 08 1986 | Yin Wood | 乙 | 丑 | Ox |

| 3 | Feb 13 1926–Feb 01 1927 | Feb 09 1986–Jan 28 1987 | Yang Fire | 丙 | 寅 | Tiger |

| 4 | Feb 02 1927–Jan 22 1928 | Jan 29 1987–Feb 16 1988 | Yin Fire | 丁 | 卯 | Rabbit |

| 5 | Jan 23 1928–Feb 09 1929 | Feb 17 1988–Feb 05 1989 | Yang Earth | 戊 | 辰 | Dragon |

| 6 | Feb 10 1929–Jan 29 1930 | Feb 06 1989–Jan 26 1990 | Yin Earth | 己 | 巳 | Snake |

| 7 | Jan 30 1930–Feb 16 1931 | Jan 27 1990–Feb 14 1991 | Yang Metal | 庚 | 午 | Horse |

| 8 | Feb 17 1931–Feb 05 1932 | Feb 15 1991–Feb 03 1992 | Yin Metal | 辛 | 未 | Goat |

| 9 | Feb 06 1932–Jan 25 1933 | Feb 04 1992–Jan 22 1993 | Yang Water | 壬 | 申 | Monkey |

| 10 | Jan 26 1933–Feb 13 1934 | Jan 23 1993–Feb 09 1994 | Yin Water | 癸 | 酉 | Rooster |

| 11 | Feb 14 1934–Feb 03 1935 | Feb 10 1994–Jan 30 1995 | Yang Wood | 甲 | 戌 | Dog |

| 12 | Feb 04 1935–Jan 23 1936 | Jan 31 1995–Feb 18 1996 | Yin Wood | 乙 | 亥 | Pig |

| 13 | Jan 24 1936–Feb 10 1937 | Feb 19 1996–Feb 06 1997 | Yang Fire | 丙 | 子 | Rat |

| 14 | Feb 11 1937–Jan 30 1938 | Feb 07 1997–Jan 27 1998 | Yin Fire | 丁 | 丑 | Ox |

| 15 | Jan 31 1938–Feb 18 1939 | Jan 28 1998–Feb 15 1999 | Yang Earth | 戊 | 寅 | Tiger |

| 16 | Feb 19 1939–Feb 07 1940 | Feb 16 1999–Feb 04 2000 | Yin Earth | 己 | 卯 | Rabbit |

| 17 | Feb 08 1940–Jan 26 1941 | Feb 05 2000–Jan 23 2001 | Yang Metal | 庚 | 辰 | Dragon |

| 18 | Jan 27 1941–Feb 14 1942 | Jan 24 2001–Feb 11 2002 | Yin Metal | 辛 | 巳 | Snake |

| 19 | Feb 15 1942–Feb 04 1943 | Feb 12 2002–Jan 31 2003 | Yang Water | 壬 | 午 | Horse |

| 20 | Feb 05 1943–Jan 24 1944 | Feb 01 2003–Jan 21 2004 | Yin Water | 癸 | 未 | Goat |

| 21 | Jan 25 1944–Feb 12 1945 | Jan 22 2004–Feb 08 2005 | Yang Wood | 甲 | 申 | Monkey |

| 22 | Feb 13 1945–Feb 01 1946 | Feb 09 2005–Jan 28 2006 | Yin Wood | 乙 | 酉 | Rooster |

| 23 | Feb 02 1946–Jan 21 1947 | Jan 29 2006–Feb 17 2007 | Yang Fire | 丙 | 戌 | Dog |

| 24 | Jan 22 1947–Feb 09 1948 | Feb 18 2007–Feb 06 2008 | Yin Fire | 丁 | 亥 | Pig |

| 25 | Feb 10 1948–Jan 28 1949 | Feb 07 2008–Jan 25 2009 | Yang Earth | 戊 | 子 | Rat |

| 26 | Jan 29 1949–Feb 16 1950 | Jan 26 2009–Feb 13 2010 | Yin Earth | 己 | 丑 | Ox |

| 27 | Feb 17 1950–Feb 05 1951 | Feb 14 2010–Feb 02 2011 | Yang Metal | 庚 | 寅 | Tiger |

| 28 | Feb 06 1951–Jan 26 1952 | Feb 03 2011–Jan 22 2012 | Yin Metal | 辛 | 卯 | Rabbit |

| 29 | Jan 27 1952–Feb 13 1953 | Jan 23 2012–Feb 09 2013 | Yang Water | 壬 | 辰 | Dragon |

| 30 | Feb 14 1953–Feb 02 1954 | Feb 10 2013–Jan 30 2014 | Yin Water | 癸 | 巳 | Snake |

| 31 | Feb 03 1954–Jan 23 1955 | Jan 31 2014–Feb 18 2015 | Yang Wood | 甲 | 午 | Horse |

| 32 | Jan 24 1955–Feb 11 1956 | Feb 19 2015–Feb 07 2016 | Yin Wood | 乙 | 未 | Goat |

| 33 | Feb 12 1956–Jan 30 1957 | Feb 08 2016–Jan 27 2017 | Yang Fire | 丙 | 申 | Monkey |

| 34 | Jan 31 1957–Feb 17 1958 | Jan 28 2017–Feb 15 2018 | Yin Fire | 丁 | 酉 | Rooster |

| 35 | Feb 18 1958–Feb 07 1959 | Feb 16 2018–Feb 04 2019 | Yang Earth | 戊 | 戌 | Dog |

| 36 | Feb 08 1959–Jan 27 1960 | Feb 05 2019–Jan 24 2020 | Yin Earth | 己 | 亥 | Pig |

| 37 | Jan 28 1960–Feb 14 1961 | Jan 25 2020–Feb 11 2021 | Yang Metal | 庚 | 子 | Rat |

| 38 | Feb 15 1961–Feb 04 1962 | Feb 12 2021–Jan 31 2022 | Yin Metal | 辛 | 丑 | Ox |

| 39 | Feb 05 1962–Jan 24 1963 | Feb 01 2022–Jan 21 2023 | Yang Water | 壬 | 寅 | Tiger |

| 40 | Jan 25 1963–Feb 12 1964 | Jan 22 2023–Feb 09 2024 | Yin Water | 癸 | 卯 | Rabbit |

| 41 | Feb 13 1964–Feb 01 1965 | Feb 10 2024–Jan 28 2025 | Yang Wood | 甲 | 辰 | Dragon |

| 42 | Feb 02 1965–Jan 20 1966 | Jan 29 2025–Feb 16 2026 | Yin Wood | 乙 | 巳 | Snake |

| 43 | Jan 21 1966–Feb 08 1967 | Feb 17 2026–Feb 05 2027 | Yang Fire | 丙 | 午 | Horse |

| 44 | Feb 09 1967–Jan 29 1968 | Feb 06 2027–Jan 25 2028 | Yin Fire | 丁 | 未 | Goat |

| 45 | Jan 30 1968–Feb 16 1969 | Jan 26 2028–Feb 12 2029 | Yang Earth | 戊 | 申 | Monkey |

| 46 | Feb 17 1969–Feb 05 1970 | Feb 13 2029–Feb 02 2030 | Yin Earth | 己 | 酉 | Rooster |

| 47 | Feb 06 1970–Jan 26 1971 | Feb 03 2030–Jan 22 2031 | Yang Metal | 庚 | 戌 | Dog |

| 48 | Jan 27 1971–Feb 14 1972 | Jan 23 2031–Feb 10 2032 | Yin Metal | 辛 | 亥 | Pig |

| 49 | Feb 15 1972–Feb 02 1973 | Feb 11 2032–Jan 30 2033 | Yang Water | 壬 | 子 | Rat |

| 50 | Feb 03 1973–Jan 22 1974 | Jan 31 2033–Feb 18 2034 | Yin Water | 癸 | 丑 | Ox |

| 51 | Jan 23 1974–Feb 10 1975 | Feb 19 2034–Feb 07 2035 | Yang Wood | 甲 | 寅 | Tiger |

| 52 | Feb 11 1975–Jan 30 1976 | Feb 08 2035–Jan 27 2036 | Yin Wood | 乙 | 卯 | Rabbit |

| 53 | Jan 31 1976–Feb 17 1977 | Jan 28 2036–Feb 14 2037 | Yang Fire | 丙 | 辰 | Dragon |

| 54 | Feb 18 1977–Feb 06 1978 | Feb 15 2037–Feb 03 2038 | Yin Fire | 丁 | 巳 | Snake |

| 55 | Feb 07 1978–Jan 27 1979 | Feb 04 2038–Jan 23 2039 | Yang Earth | 戊 | 午 | Horse |

| 56 | Jan 28 1979–Feb 15 1980 | Jan 24 2039–Feb 11 2040 | Yin Earth | 己 | 未 | Goat |

| 57 | Feb 16 1980–Feb 04 1981 | Feb 12 2040–Jan 31 2041 | Yang Metal | 庚 | 申 | Monkey |

| 58 | Feb 05 1981–Jan 24 1982 | Feb 01 2041–Jan 21 2042 | Yin Metal | 辛 | 酉 | Rooster |

| 59 | Jan 25 1982–Feb 12 1983 | Jan 22 2042–Feb 09 2043 | Yang Water | 壬 | 戌 | Dog |

| 60 | Feb 13 1983–Feb 01 1984 | Feb 10 2043–Jan 29 2044 | Yin Water | 癸 | 亥 | Pig |

Animal Trines

First

The first Trine consists of the Rat, Dragon, and Monkey. These three signs are said to be intense and powerful individuals capable of great good, who make great leaders but are rather unpredictable. The three are said to be intelligent, magnanimous, charismatic, charming, authoritative, confident, eloquent, and artistic, but can be manipulative, jealous, selfish, aggressive, vindictive, and deceitful.

Second

The second Trine consists of the Ox, Snake, and Rooster. These three signs are said to possess endurance and application, with slow accumulation of energy, meticulous at planning but tending to hold fixed opinions. The three are said to be intelligent, hard-working, modest, industrious, loyal, philosophical, patient, goodhearted, and morally upright, but can also be self-righteous, egotistical, vain, judgmental, narrow-minded, and petty.

Third

The third Trine consists of the Tiger, Horse, and Dog. These three signs are said to seek true love, to pursue humanitarian causes, to be idealistic and independent but tending to be impulsive. The three are said to be productive, enthusiastic, independent, engaging, dynamic, honorable, loyal, and protective, but can also be rash, rebellious, quarrelsome, anxious, disagreeable, and stubborn.

Fourth

The fourth Trine consists of the Rabbit, Goat, and Pig. These three signs are said to have a calm nature and somewhat reasonable approach; they seek aesthetic beauty and are artistic, well-mannered and compassionate, yet detached and resigned to their condition. The three are said to be caring, self-sacrificing, obliging, sensible, creative, empathetic, tactful, and prudent, but can also be naive, pedantic, insecure, selfish, indecisive, and pessimistic.

Compatibility

As the Chinese zodiac is derived according to the ancient Five Elements Theory, every Chinese sign is associated with five elements with relations, among those elements, of interpolation, interaction, over-action, and counter-action—believed to be the common law of motions and changes of creatures in the universe. Different people born under each animal sign supposedly have different personalities, and practitioners of Chinese astrology consult such traditional details and compatibilities to offer putative guidance in life or for love and marriage.[9]

Origin stories

There are many stories and fables to explain the beginning of the zodiac. Since the Han Dynasty, the twelve Earthly Branches have been used to record the time of day. However, for the sake of entertainment and convenience, they have been replaced by the twelve animals, and a mnemonic refers to the behavior of the animals:

Earthly Branches may refer to a double-hour period. In the latter case it is the center of the period; for instance, 马 (Horse) means noon as well as a period from 11:00 to 13:00.

| Animal | Pronunciation | Period | This is the time when... |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | Zishi | 23:00 to 00:59 | Rats are most active in seeking food. Rats also have a different number of digits on front and hind legs, thus earning Rat the symbol of "turn over" or "new start" |

| Ox | Choushi | 01:00 to 02:59 | Oxen begin to chew the cud slowly and comfortably |

| Tiger | Yinshi | 03:00 to 04:59 | Tigers hunt their prey more and show their ferocity |

| Rabbit | Maoshi | 05:00 to 06:59 | The Jade Rabbit is busy pounding herbal medicine on the Moon according to the tale |

| Dragon | Chenshi | 07:00 to 08:59 | Dragons are hovering in the sky to give rain |

| Snake | Sishi | 09:00 to 10:59 | Snakes are leaving their caves |

| Horse | Wushi | 11:00 to 12:59 | The sun is high overhead and while other animals are lying down for a rest, horses are still standing |

| Goat | Weishi | 13:00 to 14:59 | Goats eat grass and urinate frequently |

| Monkey | Shenshi | 15:00 to 16:59 | Monkeys are lively |

| Rooster | Youshi | 17:00 to 18:59 | Roosters begin to get back to their coops |

| Dog | Xushi | 19:00 to 20:59 | Dogs carry out their duty of guarding the houses |

| Pig | Haishi | 21:00 to 22:59 | Pigs are sleeping sweetly |

Great Race

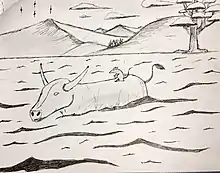

An ancient folk story[11] called the "Great Race" tells that the Jade Emperor decreed that the years on the calendar would be named for each animal in the order they reached him. To get there, the animals would have to cross a river.

The Cat and the Rat were not good at swimming, but they were both quite intelligent. They decided that the best and fastest way to cross the river was to hop on the back of the Ox. The Ox, being kindhearted and naïve, agreed to carry them both across. As the Ox was about to reach the other side of the river, the Rat pushed the Cat into the water, and then jumped off the Ox and rushed to the Jade Emperor. It was named as the first animal of the zodiac calendar. The Ox had to settle in second place.

The third one to come, was the Tiger. Even though it was strong and powerful, it explained to the Jade Emperor that the currents were pushing him downstream.

Suddenly, from a distance came a thumping sound, and the Rabbit arrived. It explained how it crossed the river: by jumping from one stone to another, in a nimble fashion. Halfway through, it almost lost the race, but it was lucky enough to grab hold of a floating log that later washed him to shore. For that, it became the fourth animal in the zodiac cycle.

In fifth place, was the flying Dragon. The Jade Emperor was wondering why such a swift airborne creature such as the Dragon did not come in first. The Dragon explained that it had to stop by a village and brought rain for all the people, and therefore it was held back. Then, on its way to the finish, it saw the helpless Rabbit clinging onto a log, so it did a good deed and gave a puff of breath to the poor creature so that it could land on the shore. The Jade Emperor was astonished by the Dragon's good nature, and it was named as the fifth animal.

As soon as it had done so, a galloping sound was heard, and the Horse appeared. Hidden on the Horse's hoof was the Snake, whose sudden appearance gave it a fright, thus making it fall back and giving the Snake the sixth spot while the Horse placed seventh.

After a while, the Goat, Monkey, and Rooster came to the heavenly gate. With combined efforts, they managed to arrive to the other side. The Rooster found a raft, and the Monkey and the Goat tugged and pulled, trying to get all the weeds out of the way. The Jade Emperor was pleased with their teamwork and decided to name the Goat as the eighth animal, followed by the Monkey and then the Rooster.

The eleventh animal placed in the zodiac cycle was the Dog. Although it should have been the best swimmer and runner, it spent its time to play in the water. Though his explanation for being late was because it needed a good bath after a long spell. For that, it almost did not make it to the finish line.

Right when the Emperor was going to end the race, an "oink" sound was heard: it was the Pig. The Pig felt hungry in the middle of the race, so it stopped, ate something, and then fell asleep. After it awoke, it finished the race in twelfth place and became the last animal to arrive.

The cat eventually drowned and failed to be in the zodiac. It is said that this is the reason cats always hunt rats and also hate water as well.

Variations

Another folk story tells that the Rat deceived the Ox into letting it jump on its back, in order for the Ox to hear the Rat sing,[12] before jumping off at the finish line and finishing first. Another variant says that the Rat had cheated the Cat out its place at the finishing line, having stowed-away on the dog's back, who was too focused to notice that he had a stow-away; this is said to account for the antagonistic dynamic between cats and rats, beyond normal predator-and-prey behaviour; and also why dogs and cats fight, the cat having tried to attack the rat in retaliation, only to get the dog by accident.

In Chinese mythology, a story tells that the cat was tricked by the Rat so it could not go to the banquet. This is why the cat is ultimately not part of the Chinese zodiac.

In Buddhism, legend has it that Gautama Buddha summoned all of the animals of the Earth to come before him before his departure from this Earth, but only twelve animals actually came to bid him farewell. To reward the animals who came to him, he named a year after each of them. The years were given to them in the order they had arrived.

The twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac were developed in the early stages of Chinese civilization, therefore it is difficult to investigate its real origins. Most historians agree that the cat is not included, as they had not yet been introduced to China from India with the arrival of Buddhism. However until recently the Vietnamese have moved away from their traditional texts[13] and literature and unlike all other countries who follow the Sino lunar calendar, have the cat instead of the rabbit as a zodiac animal. The most common explanation would be that the Cat is worshipped for luck and prosperity in East Asia by farmers to protect their crops,[14] another popular cultural reason is the ancient word for Rabbit (Mao) sounds like cat (Meo).[15]

Adaptations

The Chinese zodiac signs are also used by cultures other than Chinese. For one example, they usually appear on Korean New Year and Japanese New Year's cards and stamps. The United States Postal Service and several other countries' postal services issue a "Year of the ____" postage stamp each year to honor this Chinese heritage.

The Chinese lunar coins, depicting the zodiac animals, inspired the Canadian Silver Maple Leaf coins, as well as varieties from Australia, South Korea, and Mongolia.

The Chinese zodiac is also used in some other Asian countries that have been under the cultural influence of China. However, some of the animals in the zodiac may differ by country.

Asian

The Korean zodiac includes the Sheep (yang) instead of the Goat (which would be yeomso), although the Chinese source of the loanword yang may refer to any goat-antelope.

The Japanese zodiac includes the Sheep (hitsuji) instead of the Goat (which would be yagi), and the Wild boar (inoshishi, i) instead of the Pig (buta).[16] Since 1873, the Japanese have celebrated the beginning of the new year on 1 January as per the Gregorian calendar.

The Vietnamese zodiac varies from the Chinese zodiac with the second animal being the Water Buffalo instead of the Ox, and the fourth animal being the Cat instead of the Rabbit.

The Cambodian zodiac is exactly identical to that of the Chinese although the dragon is interchangeable with the Neak (nāga) Cambodian sea snake.[17] Sheep and Goat are interchangeable as well. The Cambodian New Year is celebrated in April, rather than in January or February as it is in China and most countries.[18][19]

The Cham zodiac uses the same order as the Chinese zodiac, but replaces the Monkey with the turtle (known locally as kra).

| Animal | Akhar Cam ꨀꨇꩉ ꨌꩌ |

Roman |

|---|---|---|

| Rat | ꨓꨪꨆꨭꩍ | Tikuh |

| Ox | ꨆꨭꨯꨝꨱ | Kubao |

| Tiger | ꨣꨪꨠꨯꨱꨮ | Rimaong |

| Rabbit | ꨓꨚꩈ | Tapay |

| Dragon | ꩓ꨘꨈꨪꨣꨰ | Inagirai |

| Snake | ꨂꨤꨘꨰꩍ | Ulanaih |

| Horse | ꨀꨔꨰꩍ | Athaih |

| Goat | ꨚꨝꨰꩈ | Pabaiy |

| Turtle | ꨆꨴ | Kra |

| Rooster | ꨠꨘꨭꩀ | Manuk |

| Dog | ꨀꨔꨭꨮ | Athau |

| Pig | ꨚꩇꨥꨪꩈ | Papwiy |

Similarly the Malay zodiac is identical to the Chinese but replaces the Rabbit with the mousedeer (pelanduk) and the Pig with the tortoise (kura or kura-kura).[20] The Dragon (Loong) is normally equated with the nāga but it is sometimes called Big Snake (ular besar) while the Snake sign is called Second Snake (ular sani). This is also recorded in a 19th-century manuscript compiled by John Leyden.[21]

| Animal | Rumi | Jawi جاوي |

|---|---|---|

| Rat | Tikus | تيکوس |

| Ox | Kerbau | کرباو |

| Tiger | Rimau | ريماو |

| Mousedeer | Pelanduk | ڤلندوق |

| Nāga | Ular Besar | اولر بسر |

| Snake | Ular Sani | اولر ثاني |

| Horse | Kuda | کودا |

| Goat | Kambing | کمبيڠ |

| Monkey | Monyet | موڽيت |

| Rooster | Ayam | أيم |

| Dog | Anjing | أنجيڠ |

| Tortoise | Kura | کورا |

The Thai zodiac includes a nāga in place of the Dragon[22] and begins, not at the Chinese New Year, but either on the first day of the fifth month in the Thai lunar calendar, or during the Songkran New Year festival (now celebrated every 13–15 April), depending on the purpose of the use.[23] Historically, Lan Na (Kingdom around Northern Thailand) also replace pig with Elephant. Modern Thai are changed back into pig, but the name กุน (gu̜n) which was meant elephant are still stuck as zodiac pronunciation [24]

The Gurung zodiac in Nepal includes a Cow instead of Ox, Cat instead of Rabbit, Eagle instead of Dragon (Loong), Bird instead of Rooster, and Deer instead of Pig.

The Bulgar calendar used from the 2nd century[25] and that has been only partially reconstructed uses a similar sixty-year cycle of twelve animal-named years groups which are:[26]

| Number | Animal | In Bulgar |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mouse | Somor |

| 2 | Ox | Shegor |

| 3 | Uncertain, probably Tiger/Wolf | Ver? |

| 4 | Rabbit | Dvan[sh] |

| 5 | Uncertain, probably Loong | Ver[eni]? |

| 6 | Snake | Dilom |

| 7 | Horse | Imen[shegor]? |

| 8 | Ram | Teku[chitem]? |

| 9 | Unattested, probably Monkey | |

| 10 | Hen or Rooster | Toh |

| 11 | Dog | Eth |

| 12 | Boar | Dohs |

The Old Mongol calendar uses the Mouse, the Ox, the Leopard, the Hare, the Crocodile, the Serpent, the Horse, the Sheep, the Monkey, the Hen, the Dog and the Hog.[27]

The Tibetan calendar replaces the Rooster with the bird.

The Volga Bulgars, Kazars and other Turkic peoples replaced some animals by local fauna: Leopard (instead of Tiger), Fish or Crocodile (instead of Dragon/Loong), Hedgehog (instead of Monkey), Elephant (instead of Pig), and Camel (instead of Rat/Mouse).[28][29]

In the Persian version of the Eastern zodiac brought by Mongols during the Middle Ages, the Chinese word lóng and Mongol word lū (Dragon) was translated as nahang meaning "water beast", and may refer to any dangerous aquatic animal both mythical and real (crocodiles, hippos, sharks, sea serpents, etc.). In the 20th century the term nahang is used almost exclusively as meaning Whale, thus switching the Loong for the Whale in the Persian variant.[30][31]

In the traditional Kazakh version of the twelve-year animal cycle (Kazakh: мүшел, müşel), the Dragon is substituted by a snail (Kazakh: ұлу, ulw), and the Tiger appears as a leopard (Kazakh: барыс, barıs).[32]

In the Kyrgyz version of the Chinese zodiac (Kyrgyz: мүчөл, müçöl) the words for the Dragon (Kyrgyz: улуу, uluu), Monkey (Kyrgyz: мечин, meçin) and Tiger (Kyrgyz: барс, bars) are only found in Chinese zodiac names, other animal names include Mouse, Cow, Rabbit, Snake, Horse, Sheep, Chicken, Dog and Wild boar.[33]

English translation

Due to confusion with synonyms during translation, some of the animals depicted by the English words did not exist in ancient China. For example:

- The term 鼠 Rat can be translated as Mouse, as there are no distinctive words for the two genera in Chinese. However, Rat is the most commonly used one among all the synonyms.

- The term 牛 Ox, a castrated Bull, can be translated interchangeably with other terms related to Cattle (male Bull, female Cow) and Buffalo. However, Ox is the most commonly used one among all the synonyms.

- The term 卯 Rabbit can be translated as Hare, as 卯 (and 兔) do not distinguish between the two genera of leporids. As hares are native to China and most of Asia and rabbits are not, this would be more accurate. However, in colloquial English Rabbit can encompass hares as well.

- The term 蛇 Snake can be translated as Serpent, which refers to a large species of snake and has the same behavior, although this term is rarely used.

- The term 羊 Goat can be translated as Sheep and Ram, a male Sheep. However, Goat is the most commonly used one among all the synonyms.

- The term 雞 Rooster can be translated interchangeably with Chicken, as well as the female Hen. However, Rooster is the most commonly used one among all the synonyms in English-speaking countries.

Gallery

See also

Notes

References

- Abe, Namiko. "The Twelve Japanese Zodiac Signs". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 2017-10-14. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- "Chinese Zodiac and Chinese Year Animals". astroica.com. Archived from the original on 2011-03-24. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- "Animals of the Thai Zodiac and the Twelve Year Cycle". Thaizer. 2011-09-08. Archived from the original on 2012-08-14. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- Theodora Lau, The Handbook of Chinese Horoscopes, pp. 2–8, 30–35, 60–64, 88–94, 118–124, 148–153, 178–184, 208–213, 238–244, 270–278, 306–312, 338–344, Souvenir Press, New York, 2005

- Ferlus, Michel (2013). The sexagesimal cycle, from China to Southeast Asia. 23rd Annual Conference of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, May 2013, Bangkok, Thailand. <halshs-00922842v2>

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014). Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- ""Almanac" "lunar" zodiac beginning of spring as the boundary dislocation?". China Network. 16 February 2009. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- "What is Your Chinese Zodiac Sign and Chinese Horoscope Zodiac Birth Chart?". Archived from the original on 2019-09-05. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- "Chinese Compatibility Matching". Jan 2016.

- "Chinese Zodiac Animal Signs Compatibility". yourchineseastrology.com/.

- "Legend of the Chinese Zodiac". www.thingsasian.com. 3 March 2003. Archived from the original on 2022-03-20. Retrieved 2022-02-01.

- Cyndi Chen (2013-02-26). "The 12 Animals of the Chinese Zodiac 十二生肖". Archived from the original on March 6, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- Jan Van Alphen, Anthony Aris Oriental Medicine: An Illustrated Guide to the Asian Arts of Healing 1995 - Page 211 "Its influence on the cultural and medical traditions of Vietnam can be clearly seen in, for example, the classical distinction between Thuoc nam, 'Southern medicine', and Thuoc bac, 'Northern or Chinese Medicine'. Both were practised and ..."

- Ronnberg, Ami; Martín, Kathleen Rock, eds. (2010). The book of symbols: archetypal reflections in word and image. Köln: Taschen. p. 300. ISBN 978-3-8365-1448-4.

- "Year of the Cat OR Year of the Rabbit?". www.nwasianweekly.com. 3 February 2011. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- "Japanese Zodiac Signs and Symbols". japanesezodiac.org/. 5 January 2012. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "Chinese Zodiac:Legend and Characteristics". windowintochina.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "The Khmer Calendar | Cambodian Religion, Festivals and Zodiac Astrology". humanoriginproject.com. 2019-04-25. Archived from the original on 2019-07-19. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Khmer Chhankitek Calendar". cam-cc.org. Archived from the original on 30 October 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Farouk Yahya (2015). "Glossary". Malay Magic and Divination in Illuminated Manuscripts. Brill. pp. 296–306. ISBN 978-90-04-30172-6.

- Leyden, John. "Cycle of years used by the Malays". Notes and vocabularies in Malay, Thai, Burmese and other minor languages. The British Library. p. 104. Retrieved 16 June 2022 – via Digitised Manuscripts.

- ""งูใหญ่-พญานาค-มังกร" รู้จัก 3 สัญลักษณ์ปี "มะโรง"". ประชาชาติธุรกิจ. 5 January 2012. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "การเปลี่ยนวันใหม่ การนับวัน ทางโหราศาสตร์ไทย การเปลี่ยนปีนักษัตร โหราศาสตร์ ดูดวง ทำนายทายทัก". Archived from the original on 2011-01-03.

- "ตุงตั๋วเปิ้ง".

- "dtrif/abv: Name list of Bulgarian hans". theo.inrne.bas.bg. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- Именник на българските ханове – ново тълкуване. М.Москов. С. 1988 г. § 80,70

- Grahame, F. R. (1860). The archer and the steppe; or, The empires of Scythia, a history of Russia. p. 258. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Davletshin1, Gamirzan M. (2015). "The Calendar and the Time Account of the Turko-Tatars". Journal of Sustainable Development. 8 (5).

- Dani, A. H.; Mohen, J.-P. History of Humanity. Vol. II: From the Third Millennium to the Seventh Century B.C. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Rasulid Hexaglot. P. B. Golden, ed., The King’s Dictionary: The Rasūlid Hexaglot – Fourteenth Century Vocabularies in Arabic, Persian, Turkic, Greek, Armenian and Mongol, tr. T. Halasi-Kun, P. B. Golden, L. Ligeti, and E. Schütz, HO VIII/4, Leiden, 2000.

- Jan Gyllenbok, Encyclopaedia of Historical Metrology, Weights, and Measures, Volume 1, 2018, p. 244.

- А. Мухамбетова (A. Mukhambetova), Казахский традиционный календарь "The traditional Kazakh calendar" Archived 2022-01-15 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- "Chinese Lunar Calendar Stamps from Kyrgyzstan". 2003.

Sources

- Shelly H. Wu. (2005). Chinese Astrology. Publisher: The Career Press, Inc. ISBN 1-56414-796-7.

External links

- "The Year of the Rooster: On Seeing"

- "The Year of the Rooster, On Eating, Injecting, Imbibing & Speaking"

- "2016: The Golden Monkey, A Year to Remember"

- "The Dragon Raises its Head 龍抬頭"

- "2019 year of the Pig"

- "From the Year of the Ape to the Year of the Monkey Archived 2020-04-11 at the Wayback Machine" (on use of Zodiac figures for political criticism)

Media related to Chinese zodiac at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chinese zodiac at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)