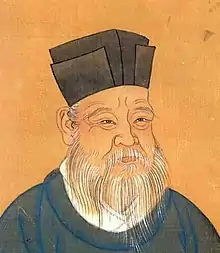

Zhu Xi

Zhu Xi ([ʈʂú ɕí]; Chinese: 朱熹; October 18, 1130 – April 23, 1200), formerly romanized Chu Hsi, was a Chinese calligrapher, historian, philosopher, poet, and politician during the Song dynasty. Zhu was influential in the development of Neo-Confucianism. He contributed greatly to Chinese philosophy and fundamentally reshaped the Chinese worldview. His works include his editing of and commentaries to the Four Books (which later formed the curriculum of the civil service exam in Imperial China from 1313 to 1905), his writings on the process of the "investigation of things" (Chinese: 格物; pinyin: géwù), and his development of meditation as a method for self-cultivation.

Zhu Xi | |

|---|---|

Zhu Xi | |

| Born | October 18, 1130 |

| Died | April 23, 1200 (aged 69) |

| Other names | Courtesy title: 元晦 Yuánhuì Alias (號): 晦庵 Huì Ān |

| Occupation(s) | Calligrapher, historian, philosopher, poet, politician |

| Era | Medieval philosophy Song Dynasty |

| Region | Chinese philosophy |

| School | Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism |

| Zhu Xi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zhu's name in regular Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 朱熹 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 朱子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Master Zhu" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

He was a scholar with a wide learning in the classics, commentaries, histories and other writings of his predecessors. In his lifetime he was able to serve multiple times as a government official,[1] although he avoided public office for most of his adult life.[2] He also wrote, compiled and edited almost a hundred books and corresponded with dozens of other scholars. He acted as a teacher to groups of students, many of whom chose to study under him for years. He built upon the teachings of the Cheng brothers and others; and further developed their metaphysical theories in regards to principle (li) and vital force (qi). His followers recorded thousands of his conversations in writing.[1]

Life

Zhu Xi, whose family originated in Wuyuan County, Huizhou (in modern Jiangxi province), was born in Fujian, where his father worked as the subprefectural sheriff. After his father was forced from office due to his opposition to the government appeasement policy towards the Jurchen in 1140, Zhu Xi received instruction from his father at home. Many anecdotes attest that he was a highly precocious child. It was recorded that at age five he ventured to ask what lay beyond Heaven, and by eight he understood the significance of the Classic of Filiality (Xiaojing). As a youth, he was inspired by Mencius' proposition that anyone could become a sage.[3] Upon his father's death in 1143, he studied with his father's friends Hu Xian, Liu Zihui, and Liu Mianzhi. In 1148, at the age of 19, Zhu Xi passed the Imperial Examination and became a presented scholar (jinshi). Zhu Xi's first official dispatch position was as Subprefectural Registrar of Tong'an (同安縣主簿), which he served from 1153 - 1156. From 1153 he began to study under Li Tong, who followed the Neo-Confucian tradition of Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi, and formally became his student in 1160.

In 1179, after not serving in an official capacity since 1156, Zhu Xi was appointed Prefect of Nankang Military District (南康軍), where he revived White Deer Grotto Academy.[4] and got demoted three years later for attacking the incompetency and corruption of some influential officials. There were several instances of receiving an appointment and subsequently being demoted. Upon dismissal from his last appointment, he was accused of numerous crimes and a petition was made for his execution. Much of this opposition was headed by Han Tuozhou, the Prime Minister, who was a political rival of Zhu's.[5][6] Even though his teachings had been severely attacked by establishment figures, almost a thousand brave people attended his funeral.[7] After the death of Han Tuozhou, Zhu's successor Zhen Dexiu, together with Wei Liaoweng, made Zhu's branch of Neo-Confucianism the dominant philosophy at the Song Court.[8][9]

In 1208, eight years after his death, Emperor Ningzong of Song rehabilitated Zhu Xi and honored him with the posthumous name of Wen Gong (文公), meaning "Venerable gentleman of culture".[10] Around 1228, Emperor Lizong of Song honored him with the posthumous noble title Duke of (State) Hui (徽國公).[11] In 1241, a memorial tablet to Zhu Xi was placed in the Confucian Temple at Qufu,[12] thereby elevating him to Confucian sainthood. Today, Zhu Xi is venerated as one of the "Twelve Philosophers" of Confucianism.[13] Modern Sinologists and Chinese often refer to him as Zhu Wen Gong (朱文公) in lieu of his name.

Teachings

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern philosophy |

|---|

|

|

The Four Books

During the Song Dynasty, Zhu Xi's teachings were considered to be unorthodox. Rather than focusing on the I Ching like other Neo-Confucians, he chose to emphasize the Four Books: the Great Learning, the Doctrine of the Mean, the Analects of Confucius, and the Mencius as the core curriculum for aspiring scholar officials. For all these classics he wrote extensive commentaries that were not widely recognized in his time; however, they later became accepted as the standard commentaries. The Four Books served as the basis of civil service examinations up until 1905,[14] and education in the classics often began with Zhu Xi's commentaries as the cornerstone for understanding them.[15]

The sources of Zhu Xi's new approach to the Confucian curriculum have been found in several works of the Cheng brothers. Zhu Xi "codified the Cheng brothers' teachings and reworked them into his own philosophical program," moving "from philology to philosophy."[16]

Vital force, principle, and the Supreme Ultimate

Zhu Xi maintained that all things are brought into being by the union of two universal aspects of reality: qi (氣, sometimes translated as vital – or physical, material – force); and li (理, sometimes translated as rational principle or law). The source and sum of li is the Taiji, meaning the Supreme Ultimate. The source of qi is not so clearly stated by Zhu Xi, leading some authorities to maintain that he was a metaphysical monist and others to maintain that he was a metaphysical dualist.

According to Zhu Xi's theory, every physical object and every person has its li and therefore has contact in its metaphysical core with the Taiji. What is referred to as the human soul, mind, or spirit is understood as the Taiji, or the supreme creative principle, as it works its way out in a person.

Qi and li operate together in mutual dependence. They are mutually aspective in all creatures in the universe. These two aspects are manifested in the creation of substantial entities. When their activity is waxing (rapid or expansive), that is the yang energy mode. When their activity is waning (slow or contractive), that is the yin energy mode. The yang and yin phases constantly interact, each gaining and losing dominance over the other. In the process of the waxing and waning, the alternation of these fundamental vibrations, the so-called five elements evolve (fire, water, wood, metal, and earth). Zhu Xi argues that li existed even before Heaven and Earth.[17]

In terms of li and qi, Zhu Xi's system strongly resembles Buddhist ideas of li (principle) and shi (affairs, matters), though Zhu Xi and his followers strongly argued that they were not copying Buddhist ideas. Instead, they held, they were using concepts already present long before in the I Ching.

Zhu Xi discussed how he saw the Supreme Ultimate concept to be compatible with principle of Taoism, but his concept of Taiji was different from the understanding of Tao in Daoism. Where Taiji is a differentiating principle that results in the emergence of something new, Dao is still and silent, operating to reduce all things to equality and indistinguishability. He argued that there is a central harmony that is not static or empty but was dynamic, and that the Supreme Ultimate is itself in constant creative activity.

Human nature

Zhu Xi considered the earlier Confucian Xunzi to be a heretic for departing from Mengzi's idea of innate human goodness. Even if people displayed immoral behaviour, the supreme regulative principle was good. The cause of immoral actions is qi. Zhu Xi's metaphysics is that everything contains li and qi. Li is the principle that is in everything and governs the universe. Each person has a perfect li. As such, individuals should act in perfect accordance with morality. However, while li is the underlying structure, qi is also part of everything. Qi obscures our perfect moral nature. The task of moral cultivation is to clear our qi. If our qi is clear and balanced, then we will act in a perfectly moral way.

Heart/mind

"Heart" and "mind" are both expressed in Chinese with the same word xin (心); clarity of mind and purity of heart are ideal in Confucian philosophy. In the following poem, "Reflections While Reading - 1" Zhu Xi illustrates this concept by comparing the mind to a mirror, left covered until needed that simply reflects the world around it, staying clear by the flowing waters symbolizing the Tao. In Chinese, the mind was sometimes called "the square inch", which is the literal translation of the term alluded to in the beginning of the poem.[15]

半畝方塘一鑑開, |

A small square pond an uncovered mirror |

| —translation by Red Pine |

Knowledge and action

According to Zhu Xi's epistemology, knowledge and action were indivisible components of truly intelligent activity. Although he did distinguish between the priority of knowing, since intelligent action requires forethought, and the importance of action, as it produces a discernible effect, Zhu Xi said "Knowledge and action always require each other. It is like a person who cannot walk without legs although he has eyes, and who cannot see without eyes although he has legs. With respect to order, knowledge comes first, and with respect to importance, action is more important."[18]

The investigation of things and the extension of knowledge

Zhu Xi advocated the investigation of things (格物致知; gewu zhizhi). How to investigate and what these things are is the source of much debate. To Zhu Xi, the things are moral principles and the investigation involves paying attention to everything in both books and affairs[19] because "moral principles are quite inexhaustible".[20]

Religion

Zhu Xi did believe in the existence of spirits, ghosts, divination, and blessings.[21]

Meditation

Zhu Xi practiced a form of daily meditation called jingzuo similar to, but not the same as, Buddhist dhyana or chan ding (禪定; Wade–Giles chʻan-ting). His meditation did not require the cessation of all thinking as in some forms of Buddhism; rather, it was characterised by quiet introspection that helped to balance various aspects of one's personality and allowed for focused thought and concentration.

His form of meditation was by nature Confucian in the sense that it was concerned with morality. His meditation attempted to reason and feel in harmony with the universe. He believed that this type of meditation brought humanity closer together and more into harmony.[22]

On teaching, learning, and the creation of an academy

Zhu Xi heavily focused his energy on teaching, claiming that learning is the only way to sage-hood. He wished to make the pursuit of sage-hood attainable to all men.

He lamented more modern printing techniques and the proliferation of books that ensued. This, he believed, made students less appreciative and focused on books, simply because there were more books to read than before. Therefore, he attempted to redefine how students should learn and read. In fact, disappointed by local schools in China, he established his own academy, White Deer Grotto Academy, to instruct students properly and in the proper fashion.

Taoist and Buddhist influence on Zhu Xi

Zhu Xi wrote what was to become the orthodox Confucian interpretation of a number of concepts in Taoism and Buddhism. While he appeared to have adopted some ideas from these competing systems of thought, unlike previous Neo-Confucians he strictly abided by the Confucian doctrine of active moral cultivation. He found Buddhist principles to be darkening and deluding the original mind[23] as well as destroying human relations.[24]

Legacy

From 1313 to 1905, Zhu Xi's commentaries on the Four Books formed the basis of civil service examinations in China.[14] His teachings were to dominate Neo-Confucians such as Wang Fuzhi, though dissenters would later emerge such as Wang Yangming and the School of Mind two and a half centuries later.

His philosophy survived the Intellectual Revolution of 1917, and later Feng Youlan would interpret his conception of li, qi, and taiji into a new metaphysical theory.

He was also influential in Japan known as Shushigaku (朱子学, School of Master Zhu), and in Korea known as Jujahak (주자학), where it became an orthodoxy.

Life magazine ranked Zhu Xi as the forty-fifth most important person in the last millennium.

Zhu Xi's descendants, like those of Confucius and other notable Confucians, held the hereditary title of Wujing Boshi (五经博士; 五經博士; Wǔjīng Bóshì),[25][26] which translated means Erudite or Doctor of the Five Classics and enjoyed the rank of 8a in the Mandarin (bureaucrat) system.[27]

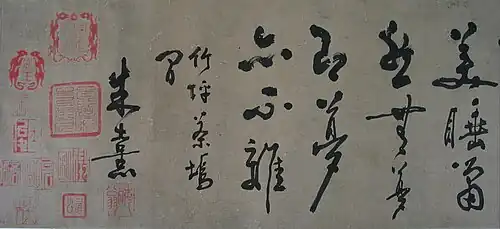

Calligraphy

Zhu Xi had, from an early age, followed his father and a number of great calligraphers at the time in practicing calligraphy. At first he learned the style of Cao Cao, but later specialized in the regular script of Zhong Yao and the running cursive script of Yan Zhenqing. Though his manuscripts left to the world are piecemeal and incomplete, and most of his works are lost. Moreover, his fame in the realm of philosophy was so great that even his brilliance in calligraphy was overshadowed. He was skillful in both running and cursive scripts, especially in large characters, but extant artworks consist mainly of short written notes in running script and rarely of large characters. His authentic manuscripts are collected by Nanjing Museum, Beijing Palace Museum, Liaoning Province Museum, Taipei Palace Museum and the National Museum of Tokyo, Japan. Some pieces are in private collections in China and overseas. The Thatched Hut Hand Scroll, one of Zhu Xi's masterpieces in running-cursive script, is in an overseas private collection.

Thatched Hut Hand Scroll contains three separate parts:

- Title

- 102 characters by Zhu Xi in running cursive scripts

- The postscripts by Wen Tianxiang (1236~1283) of Song dynasty, Fang Xiaoru (1375~1402), Zhu Yunming (1460–1526), Tang Yin (1470~1523) and Hai Rui (1514~1587) of the Ming dynasty.

Calligraphy style

The calligraphy of Zhu Xi had been acclaimed as acquiring the style of the Han and Wei dynasties. He was skillful in the central tip, and his brush strokes are smooth and round, steady yet flowing in the movements without any trace of frivolity and abruptness. Indeed, his calligraphy possesses stability and elegance in construction with a continuous flow of energy. Without trying to be pretentious or intentional, his written characters are well-balanced, natural and unconventional. As he was a patriarch of Confucianism philosophy, it is understandable that his learning permeated in all his writings with due respect for traditional standards. He maintained that while rules had to be observed for each word, there should be room for tolerance, multiplicity and naturalness. In other words, calligraphy had to observe rules and at the same time not be bound by them so as to express the quality of naturalness. It is small wonder that his calligraphy had been highly esteemed throughout the centuries, by great personages as follows:

Tao Chung Yi (around 1329~1412) of the Ming dynasty:

Whilst Master Zhu inherited the orthodox teaching and propagated it to the realm of sages and yet he was also proficient in running and cursive scripts, especially in large characters. His execution of brush was well-poised and elegant. However piecemeal or isolated his manuscripts, they were eagerly sought after and treasured.

Wang Sai Ching (1526–1590) of the Ming dynasty:

The brush strokes in his calligraphy were swift without attempting at formality, yet none of his strokes and dots were not in conformity with the rules of calligraphy.

Wen Tianxiang of the Song dynasty in his postscript for the Thatched Hut Hand Scroll by Zhu Xi:

People in the olden days said that there was embedded the bones of loyal subject in the calligraphy of Yan Zhenqing. Observing the execution of brush strokes by Zhu Xi, I am indeed convinced of the truth of this opinion.

Zhu Yunming of the Ming dynasty in his postscript for the Thatched Hut Hand Scroll by Zhu Xi:

Master Zhu was loyal, learned and a great scholar throughout ages . He was superb in calligraphy although he did not write much in his lifetime and hence they were rarely seen in later ages. This roll had been collected by Wong Sze Ma for a long time and of late, it appeared in the world. I chanced to see it once and whilst I regretted that I did not try to study it extensively until now, in the study room of my friend, I was so lucky to see it again. This showed that I am destined to see the manuscripts of master Zhu. I therefore wrote this preface for my intention.

Hai Rui of the Ming dynasty in his postscript for the Thatched Hut Hand Scroll by Zhu Xi:

The writings are enticing, delicate, elegant and outstanding. Truly such calligraphy piece is the wonder of nature.

See also

- Confucianism

- Neo-Confucianism

- Zhou Dunyi

- Lu Jiuyuan

- Wang Yangming

- Wang Fuzhi

- Feng Youlan

- Yuelu Academy

- White Deer Grotto Academy

- Classical Chinese writers

- Yi Hwang or Toegye, A Korean Confucian scholar of the Joseon Dynasty

- Yi I or Yulgok, A Korean Confucian scholar of the Joseon Dynasty

- Fujiwara Seika, Japanese follower of the philosophy of Zhu Xi

- Hayashi Razan, Seika's student & Tokugawa political theorist

- Hayashi Gahō, Tokugawa shogunate academician/scholar/bureaucrat

- Kaibara Ekken, Edo period writer/botanist/philosopher

Footnotes and references

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1993). Chinese civilization : a sourcebook (2nd ed.). New York: The Free Press. pp. 172. ISBN 002908752X. OCLC 27226697.

- Confucius, Edward; Slingerland (2006). The Essential Analects: Selected Passages with Traditional Commentary. Hackett Publishing. pp. 148–9. ISBN 1-60384-346-9.

- Thompson, Kirill (2017). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Gardner, pp. 3 - 6

- Xu, Haoran. "The Relationship Between Zhen Dexiu and Neo-Confucianism:under the Background of an Imperial Edict Drafter". CNKI. Journal of Peking University (philosophy of Social Sciences). Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Rodney Leon Taylor; Howard Yuen Fung Choy (January 2005). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Confucianism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-8239-4080-6.

- Chan 1963: 588.

- Bettine Birge (7 January 2002). Women, Property, and Confucian Reaction in Sung and Yüan China (960–1368). Cambridge University Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-139-43107-1.

- "Writings of the Orthodox School". World Digital Library. Library of Congress. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Chan 1989: 34.

- Chan 1989: 34. Hui refers to Hui-chou his ancestral place in Anhui, now Jiangxi.

- Gardner 1989: 9.

- "World Architecture Images- Beijing- Confucius Temple". Chinese-architecture.info. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- Chan 1963: 589.

- Red Pine, Poems of the Masters, Copper Canyon Press, 2003, p. 164.

- Lianbin Dai, "From Philology to Philosophy: Zhu Xi (1130–1200) as a Reader-Annotator." In Canonical Texts and Scholarly Practices: A Global Comparative Approach, edited by Anthony Grafton and Glenn W. Most, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016, 136–163 (136).

- Zhu Xi 1986, Zhuzi yulei, Beijing; Zhonghua Shuju, p.1

- The Complete Works of Chu Hsi, section 20 in Chan 1963: 609.

- The Complete Works of Chu Hsi, section 26 in Chan 1963: 609.

- The Complete Works of Chu Hsi, section 27 in Chan 1963: 610.

- "Varieties of Spiritual Experience: Shen in Neo-Confucian Discourse".

- Pavlac, Brian A. (2005). The Middle Ages. Passadena, CA: Salem Press Inc. pp. 491–492. ISBN 1-58765-168-8.

- The Complete Works of Chu Hsi, section 147 in Chan 1963: 653.

- The Complete Works of Chu Hsi, section 138 in Chan 1963: 647.

- H.S. Brunnert; V.V. Hagelstrom (15 April 2013). Present Day Political Organization of China. Routledge. p. 494. ISBN 978-1-135-79795-9.

- Chang Woei Ong (2008). Men of Letters Within the Passes: Guanzhong Literati in Chinese History, 907-1911. Harvard University Asia Center. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-674-03170-8.

- Charles O. Hucker (1 April 2008). A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Peking University Press. p. 569. ISBN 978-7-301-13487-0.

Further reading

- J. Percy Bruce. Chu Hsi and His Masters, Probsthain & Co., London, 1922.

- Daniel K. Gardner. Learning To Be a Sage, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1990. ISBN 0-520-06525-5.

- Bruce E. Carpenter. 'Chu Hsi and the Art of Reading' in Tezukayama University Review (Tezukayama daigaku ronshū), Nara, Japan, no. 15, 1977, pp. 13–18. ISSN 0385-7743

- Wing-tsit Chan, Chu Hsi: Life and Thought (1987). ISBN 0-312-13470-3.

- Wing-tsit Chan, Chu Hsi: New Studies. University of Hawaii Press: 1989. ISBN 978-0-8248-1201-0

- Gedalecia, D (1974). "Excursion Into Substance and Function." Philosophy East and West. vol. 4, 443–451.

- Hoyt Cleveland Tillman, Utilitarian Confucianism: Ch‘en Liang's Challenge to Chu Hsi (1982)

- Wm. Theodore de Bary, Neo-Confucian Orthodoxy and the Learning of the Mind-and-Heart (1981), on the development of Zhu Xi's thought after his death

- Wing-tsit Chan (ed.), Chu Hsi and Neo-Confucianism (1986), a set of conference papers

- Donald J. Munro, Images of Human Nature: A Sung Portrait (1988), an analysis of the concept of human nature in Zhu Xi's thought

- Joseph A. Adler, Reconstructing the Confucian Dao: Zhu Xi's Appropriation of Zhou Dunyi (2014), a study of how and why Zhu Xi chose Zhou Dunyi to be the first true Confucian Sage since Mencius

- Lianbin Dai, "From Philology to Philosophy: Zhu Xi (1130–1200) as a Reader-Annotator" (2016). In Canonical Texts and Scholarly Practices: A Global Comparative Approach, edited by Anthony Grafton and Glenn W. Most, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016, 136–163, on Zhu Xi within the context and development of neo-Confucianism

Translations

All translations are of excerpts except where otherwise noted.

- McClatchie, Thomas (1874). Confucian Cosmogony: A Translation of Section Forty-nine of the Complete Works of the Philosopher Choo-Foo-Tze. Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission.

- Bruce, J. Percy (1922). The philosophy of human nature. London: Probsthain.

- Wing-tsit Chan (1963), A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gardner, Daniel (1986). Chu Hsi and Ta-hsueh: Neo-Confucian Reflection on the Confucian Canon. Cambridge: Harvard UP.

- Chan, Wing-tsit (1967). Reflections On Things at Hand. New York: Columbia University Press.

- A full translation of 近思錄.

- Gardner, Daniel K. (1990). Learning to be a sage: selections from the Conversations of Master Chu, arranged topically. Berkeley: U. California Press. ISBN 0520909046.

- Wittenborn, Allen (1991). Further reflections on things at hand. Lanham: University Press of America. ISBN 0819183725.

- A full translation of 續近思錄.

- Ebrey, Patricia (1991). Chu Hsi's family rituals. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691031495.

- A full translation of 家禮.

- Adler, Joseph A. (2002). Introduction to the study of the classic of change (I-hsüeh ch'i-meng). Provo, Utah: Global Scholarly Publications.

- A full translation of 易學啟蒙.

- Adler, Joseph A. (2014). Reconstructing the Confucian Dao: Zhu Xi's Appropriation of Zhou Dunyi). Albany: SUNY Press.

- Full translation of Zhu Xi's commentaries on Zhou Dunyi's Taijitu shuo 太極圖說 and Tongshu 通書.

- Adler, Joseph A. (2020). The Original Meaning of the Yijing: Commentary on the Scripture of Change. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Full translation of Zhu Xi's Zhouyi benyi 周易本義, with Introduction and annotations.

External links

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Zhu Xi". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Zhu Xi (Chu Hsi, 1130—1200)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Zhu Xi and his Calligraphy Gallery at China Online Museum

- Zhu Xi's large-character calligraphy from the Yijing

- Chu Hsi and Divination - Joseph A. Adler

- Works by Zhu Xi at Project Gutenberg

- First part of the Classified Conversations of Master Zhu