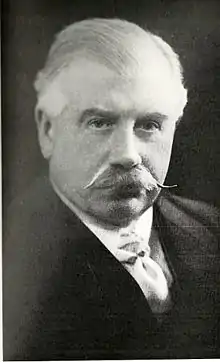

Henry Wood

Sir Henry Joseph Wood CH (3 March 1869 – 19 August 1944) was an English conductor best known for his association with London's annual series of promenade concerts, known as the Proms. He conducted them for nearly half a century, introducing hundreds of new works to British audiences. After his death, the concerts were officially renamed in his honour as the "Henry Wood Promenade Concerts", although they continued to be generally referred to as "the Proms".

Born in modest circumstances to parents who encouraged his musical talent, Wood started his career as an organist. During his studies at the Royal Academy of Music, he came under the influence of the voice teacher Manuel García and became his accompanist. After similar work for Richard D'Oyly Carte's opera companies on the works of Arthur Sullivan and others, Wood became the conductor of a small operatic touring company. He was soon engaged by the larger Carl Rosa Opera Company. One notable event in his operatic career was conducting the British premiere of Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin in 1892.

From the mid-1890s until his death, Wood focused on concert conducting. He was engaged by the impresario Robert Newman to conduct a series of promenade concerts at the Queen's Hall, offering a mixture of classical and popular music at low prices. The series was successful, and Wood conducted annual promenade series until his death in 1944. By the 1920s, Wood had steered the repertoire entirely to classical music. When the Queen's Hall was destroyed by bombing in 1941, the Proms moved to the Royal Albert Hall.

Wood declined the chief conductorships of the New York Philharmonic and Boston Symphony Orchestras, believing it his duty to serve music in the United Kingdom. In addition to the Proms, he conducted concerts and festivals throughout the country and also trained the student orchestra at the Royal Academy of Music. He had an enormous influence on the musical life of Britain over his long career: he and Newman greatly improved access to classical music, and Wood raised the standard of orchestral playing and nurtured the taste of the public, presenting a vast repertoire of music spanning four centuries.

Biography

Early years

Wood was born in Oxford Street, London, the only child of Henry Joseph Wood and his wife Martha, née Morris. Wood senior had started in his family's pawnbroking business, but by the time of his son's birth he was trading as a jeweller, optician and engineering modeller, much sought-after for his model engines.[1] It was a musical household: Wood senior was an amateur cellist and sang as principal tenor in the choir of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate, known as "the musicians' church".[n 1] His wife played the piano and sang songs from her native Wales. They encouraged their son's interest in music, buying him a Broadwood piano, on which his mother gave him lessons.[3] The young Wood also learned to play the violin and viola.[4]

Wood received little religious inspiration at St Sepulchre, but was deeply stirred by the playing of the resident organist, George Cooper, who allowed him into the organ loft and gave him his first lessons on the instrument.[5] Cooper died when Wood was seven, and the boy took further lessons from Cooper's successor, Edwin M. Lott, for whom Wood had much less regard.[4] At the age of ten, through the influence of one of his uncles, Wood made his first paid appearance as an organist at St Mary Aldermanbury, being paid half a crown.[n 2] In June 1883, visiting the International Fisheries Exhibition at South Kensington with his father, Wood was invited to play the organ in one of the galleries, making a good enough impression to be engaged to give recitals at the exhibition building over the next three months.[7] At this time in his life, painting was nearly as strong an interest as music, and he studied in his spare time at the Slade School of Fine Art. He remained a life-long amateur painter.[n 3]

After taking private lessons from the musicologist Ebenezer Prout, Wood entered the Royal Academy of Music at the age of seventeen, studying harmony and composition with Prout, organ with Charles Steggall, and piano with Walter Macfarren. It is not clear whether he was a member of Manuel Garcia's singing class,[n 4] but it is certain that he became its accompanist and was greatly influenced by Garcia.[10] Wood also accompanied the opera class, taught by Garcia's son Gustave.[11] Wood's ambition at the time was to become a teacher of singing, and he gave singing lessons throughout his life. He attended the classes of as many singing teachers as he could,[10] although by his own account, "I possess a terrible voice. Garcia said it would go through a brick wall. In fact, a real conductor's voice."[12]

Opera

On leaving the Royal Academy of Music in 1888, Wood taught singing privately and was soon very successful, attracting "more singing pupils than I could comfortably deal with"[13] at half a guinea an hour.[n 5] He also worked as a répétiteur. According to his memoirs, he worked in that capacity for Richard D'Oyly Carte during the rehearsals for the first production of The Yeomen of the Guard at the Savoy Theatre in 1888.[14] His biographer Arthur Jacobs doubts this and discounts exchanges Wood purported to have had with Sir Arthur Sullivan about the score.[15] Jacobs describes Wood's memoirs as "vivacious in style but factually unreliable".[16]

It is certain, however, that Wood was répétiteur at Carte's Royal English Opera House for Sullivan's grand opera Ivanhoe in late 1890 and early 1891, and for André Messager's La Basoche in 1891–92.[17] He also worked for Carte at the Savoy as assistant to François Cellier on The Nautch Girl in 1891.[17] Wood remained devoted to Sullivan's music and later insisted on programming his concert works when they were out of fashion in musical circles.[18] During this period, he had several compositions of his own performed, including an oratorio, St. Dorothea (1889), a light opera, Daisy (1890), and a one-act comic opera, Returning the Compliment (1890).[17]

Wood recalled that his first professional appearance as a conductor was at a choral concert in December 1887. Ad hoc engagements of this kind were commonplace for organists, but they brought little prestige such as was given to British conductor-composers such as Sullivan, Charles Villiers Stanford and Alexander Mackenzie, or the rising generation of German star conductors led by Hans Richter and Arthur Nikisch.[19] His first sustained work as a conductor was his 1889 appointment as musical director of a small touring opera ensemble, the Arthur Rouseby English Touring Opera. The company was not of a high standard, with an orchestra of only six players augmented by local recruits at each tour venue. Wood eventually negotiated a release from his contract,[20] and after a brief return to teaching he secured a better appointment as conductor for the Carl Rosa Opera Company in 1891. For that company he conducted Carmen, The Bohemian Girl, The Daughter of the Regiment, Maritana, and Il trovatore.[21] This appointment was followed by a similar engagement with a company set up by former Carl Rosa singers.[22]

When Signor Lago, formerly impresario of the Imperial Opera Company of St. Petersburg, was looking for a second conductor to work with Luigi Arditi for a proposed London season, Garcia recommended Wood.[23] The season opened at the newly rebuilt Olympic Theatre in London, in October 1892, with Wood conducting the British premiere of Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin.[24] At that time the operatic conductor was not seen as an important figure, but the critics who chose to mention the conducting gave Wood good reviews.[n 6] The work was not popular with the public, and the season was cut short when Lago absconded, leaving the company unpaid.[26] Before that debacle, Wood had also conducted performances of Maritana and rehearsed Oberon and Der Freischütz.[17] After the collapse of the Olympic opera season, Wood returned once more to his singing tuition. In 1894 he contributed to a song in the operetta The Lady Slavey[27] and also conducted performances during its three month London run.[28][29] With the exception of a season at the Opera Comique in 1896, Wood's subsequent conducting career was in the concert hall.[30]

Early years of the Proms

In 1894, Wood went to the Wagner festival at Bayreuth where he met the conductor Felix Mottl,[8] who subsequently appointed him as his assistant and chorus master for a series of Wagner concerts at the newly built Queen's Hall in London.[31] The manager of the hall, Robert Newman, was proposing to run a ten-week season of promenade concerts and, impressed by Wood, invited him to conduct.[31] There had been such concerts in London since 1838, under conductors from Louis Antoine Jullien to Arthur Sullivan.[32] Sullivan's concerts in the 1870s had been particularly successful, because he offered his audiences something more than the usual light music. He introduced major classical works, such as Beethoven symphonies, normally restricted to the more expensive concerts presented by the Philharmonic Society and others.[33] Newman aimed to do the same: "I am going to run nightly concerts and train the public by easy stages. Popular at first, gradually raising the standard until I have created a public for classical and modern music."[34]

Newman's determination to make the promenade concerts attractive to everyone led him to permit smoking during concerts, which was not formally prohibited at the Proms until 1971.[35] Refreshments were available in all parts of the hall throughout the concerts, not only during intervals.[36] Prices were considerably lower than those customarily charged for classical concerts: the promenade (the standing area) was one shilling, the balcony two shillings, and the grand circle (reserved seats) three and five shillings.[37][n 7]

Newman needed to find financial backing for his first season. Dr George Cathcart, a wealthy ear, nose and throat specialist, offered to sponsor it on two conditions: that Wood should conduct every concert, and that the pitch of the orchestral instruments should be lowered to the European standard diapason normal. Concert pitch in England was nearly a semitone higher than that used on the continent, and Cathcart regarded it as damaging for singers' voices.[38] Wood, from his experience as a singing teacher, agreed.[39] As members of Wood's brass and woodwind sections were unwilling to buy new low-pitched instruments, Cathcart imported a set from Belgium and lent them to the players. After a season, the players recognised that the low pitch would be permanently adopted, and they bought the instruments from him.[38]

On 10 August 1895, the first of the Queen's Hall Promenade Concerts took place. Among those present who later recalled the opening was the singer Agnes Nicholls:[40]

Just before 8 o'clock I saw Henry Wood take up his position behind the curtain at the end of the platform – watch in hand. Punctually, on the stroke of eight, he walked quickly to the rostrum, buttonhole and all, and began the National Anthem ... A few moments for the audience to settle down, then the Rienzi Overture, and the first concert of the new Promenades had begun.

The rest of the programme comprised, in the words of an historian of the Proms, David Cox, "for the most part ... blatant trivialities."[41] Within days, however, Wood was shifting the balance from light music to mainstream classical works, with Schubert's Unfinished Symphony and further excerpts from Wagner operas.[42] Among the other symphonies Wood conducted during the first season were Schubert's Great C Major, Mendelssohn's Italian and Schumann's Fourth. The concertos included Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto and Schumann's Piano Concerto.[43] During the season Wood presented 23 novelties, including the London premieres of pieces by Richard Strauss, Tchaikovsky, Glazunov, Massenet and Rimsky-Korsakov.[44] Newman and Wood soon felt able to devote every Monday night of the season principally to Wagner and every Friday night to Beethoven, a pattern that endured for decades.[45]

The income from the concerts did not permit generous rehearsal time. Wood had nine hours to rehearse all the music for each week's six concerts.[46] To gain the best results on so little rehearsal, Wood developed two facets of his conducting that remained his trademark throughout his career. First, he bought sets of the orchestral parts and marked them all with minutely detailed instructions to the players; secondly he developed a clear and expressive conducting technique. An orchestral cellist wrote that "if you watched him, you couldn't come in wrong."[47] The violist Bernard Shore wrote, "You may be reading at sight in public, but you can't possibly go wrong with that stick in front of you".[48] Thirty-five years after Wood's death, André Previn recounted a story by one of his players who recalled that Wood "had everything planned out and timed to the minute ... at 10 a.m. precisely his baton went down. You learned things so thoroughly with him, but in the most economical time."[49]

Another feature of Wood's conducting was his insistence on accurate tuning; before each rehearsal and concert he would check the instrument of each member of the woodwind and string sections against a tuning fork.[50] He persisted in this practice until 1937, when the excellence of the BBC Symphony Orchestra persuaded him that it was no longer necessary.[51] To improve ensemble, Wood experimented with the layout of the orchestra. His preferred layout was to have the first and second violins grouped together on his left, with the cellos to his right, a layout that has since become common.[52]

Between the first and second season of promenade concerts, Wood did his last work in the opera house, conducting Stanford's new opera Shamus O'Brien at the Opera Comique. It ran from March until July 1896, leaving Wood enough time to prepare the second Queen's Hall season, which began at the end of August.[53] The season was so successful that Newman followed it with a winter season of Saturday night promenade concerts, but despite being popular they were not a financial success, and were not repeated in later years.[54]

In January 1897, Wood took on the direction of the Queen's Hall's prestigious Saturday afternoon symphony concerts.[16] He continually presented new works by composers of many nationalities, and was particularly known for his skill in Russian music. Sullivan wrote to him in 1898, "I have never heard a finer performance in England than that of the Tchaikovsky symphony under your direction last Wednesday".[55] Seventy-five years later, Sir Adrian Boult ranked Wood as one of the two greatest Tchaikovsky conductors in his long experience.[56] Wood also successfully challenged the widespread belief that Englishmen were not capable of conducting Wagner.[57] When Wood and the Queen's Hall Orchestra performed at Windsor Castle in November 1898, Queen Victoria chose Tchaikovsky and Wagner for the programme.[16] Wood, who modelled his appearance on Nikisch, took it as a compliment that the queen said to him, "Tell me, Mr Wood, are you quite English?"[58]

In 1898, Wood married one of his singing pupils, Olga Michailoff, a divorcée a few months his senior.[n 8] Jacobs describes it as "a marriage of perfect professional and private harmony".[59] As a singer, with Wood as her accompanist, she won praise from the critics.[60]

Early 20th century

The promenade concerts flourished through the 1890s, but in 1902 Newman, who had been investing unwisely in theatrical presentations, found himself unable to bear the financial responsibility for the Queen's Hall Orchestra and was declared bankrupt. The concerts were rescued by the musical benefactor Sir Edgar Speyer, a banker of German origin. Speyer put up the necessary funds, retained Newman as manager of the concerts, and encouraged him and Wood to continue with their project of improving the public's taste.[61] At the beginning of 1902, Wood accepted the conductorship of that year's Sheffield triennial festival. He continued to be associated with that festival until 1936, changing its emphasis from choral to orchestral pieces. A German critic, reviewing the festival for a Berlin publication, wrote, "Two personalities now represent a new epoch in English musical life – Edward Elgar as composer, and Henry J. Wood as conductor."[62]

Later that year, overtaxed by his enormous workload, Wood's health broke down. Even though this was during the Proms season, Cathcart insisted that Wood should have a complete break and change of scene. Leaving the leader of the orchestra, Arthur Payne, to conduct during his absence, Wood and his wife took a cruise to Morocco, missing the Proms concerts from 13 October to 8 November.[63]

In the early years of the Proms there were complaints in some musical journals that Wood was neglecting British music.[64] In 1899, Newman unsuccessfully attempted to secure for Wood the premiere of Elgar's Enigma Variations,[65] but in the same year Newman passed up the opportunity to introduce the music of Delius to London concertgoers.[66] By the end of the first decade of the new century, however, Wood's reputation in conducting British music was in no doubt; he gave the world, British or London premieres of more than a hundred British works between 1900 and 1910.[63][67] Meanwhile, he introduced his audiences to many European composers. In the 1903 season, he programmed symphonies by Bruckner (No. 7), Sibelius (No. 1), and Mahler (No. 1). In the same year, he introduced several of Richard Strauss's tone poems to London, and in 1905 he gave Strauss's Symphonia Domestica. This prompted the composer to write, "I cannot leave London without an expression of admiration for the splendid Orchestra which Henry Wood's master hand has created in such a short time."[68]

Creating the orchestra admired by Strauss had not been achieved without a struggle. In 1904, Wood and Newman tackled the deputy system, in which orchestral players, if offered a better-paid engagement, could send a substitute to a rehearsal or a concert. The treasurer of the Royal Philharmonic Society described it thus: "A, whom you want, signs to play at your concert. He sends B (whom you don't mind) to the first rehearsal. B, without your knowledge or consent, sends C to the second rehearsal. Not being able to play at the concert, C sends D, whom you would have paid five shillings to stay away."[69] After a rehearsal in which Wood was faced with a sea of entirely unfamiliar faces in his own orchestra, Newman came on the platform to announce: "Gentlemen, in future there will be no deputies; good morning."[70] Forty players resigned en bloc and formed their own orchestra: the London Symphony Orchestra. Wood bore no grudge and attended their first concert, although it was 12 years before he agreed to conduct the orchestra.[71]

Wood had great sympathy for rank-and-file orchestral players and strove for improvements in their pay.[72] He sought to raise their status and was the first British conductor to insist that the orchestra should stand to acknowledge applause along with the conductor.[73] He introduced women into the Queen's Hall Orchestra in 1913.[9] He said, "I do not like ladies playing the trombone or double bass, but they can play the violin, and they do."[74] By 1918 Wood had 14 women in his orchestra.[75]

Wood conducted his own compositions and arrangements from time to time. He gave his Fantasia on Welsh Melodies and Fantasia on Scottish Melodies on successive nights in 1909. He composed the work for which he is most celebrated, Fantasia on British Sea Songs, for a concert in 1905, celebrating the centenary of the Battle of Trafalgar. It caught the public fancy immediately, with its mixture of sea-shanties, together with Handel's "See the Conquering Hero Comes" and Arne's "Rule, Britannia!" He played it at the Proms more than 40 times, and it became a fixture at the "Last Night of the Proms", the lively concert marking the end of each season. It remained so under his successors, though often rearranged, notably by Sir Malcolm Sargent.[76][n 9] A highlight of the Fantasia is the hornpipe ("Jack's the Lad"); Wood said of it:

They stamp their feet in time to the hornpipe – that is until I whip up the orchestra to a fierce accelerando which leaves behind all those whose stamping technique is not of the very finest quality. I like to win by two bars, if possible; but sometimes have to be content with a bar and a half. It is good fun, and I enjoy it as much as they.[80]

Among Wood's other works was his Purcell Suite, incorporating themes from Purcell's stage works and string sonatas, which Wood performed at an orchestral festival in Zurich in 1921, and orchestral transcriptions of works by a range of composers from Albéniz to Vivaldi.[81]

Wood worked with his wife for many concerts, and was her piano accompanist at her recitals. In 1906, at the Norwich music festival he presented Beethoven's Choral Symphony and Bach's St Matthew Passion, with his wife among the singers.[82]

In December 1909, after a short illness, Olga Wood died.[83] Cathcart took Wood away to take his mind off his loss.[n 10] On his return, Wood resumed his professional routine, with the exception that, after Olga's death, he rarely performed as piano accompanist for anyone else; his skill in that art was greatly missed by the critics.[84]

In June 1911, he married his secretary, Muriel Ellen Greatrex (1882–1967), with whom he had two daughters.[85] In the same year he accepted a knighthood,[86] and declined the conductorship of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in succession to Mahler, as he felt it his duty to devote himself to the British public.[87]

Throughout the early part of the century, Wood was influential in changing the habits of concertgoers. Until then it had been customary for audiences at symphony or choral concerts to applaud after each movement or section. Wood discouraged this, sometime by gesture and sometimes by specific request printed in programmes. For this he was much praised in the musical and national press.[88] In addition to his work at the Queen's Hall, Wood conducted at the Sheffield, Norwich, Birmingham, Wolverhampton, and Westmorland festivals, and at orchestral concerts in Cardiff, Manchester, Liverpool, Leicester and Hull.[8] His programming was summarised in The Manchester Guardian, which listed the number of each composer's works played in the 1911 Proms season; the top ten were: Wagner (121); Beethoven (34); Tchaikovsky (30); Mozart (28); Dvořák (16); Weber (16); J.S. Bach (14); Brahms (14); Elgar (14); and Liszt (13).[89]

.jpg.webp)

The 1912 and 1913 Prom seasons are singled out by Cox as among the finest of this part of Wood's career. Among those conducting their own works or hearing Wood conduct them were Strauss, Debussy, Reger, Scriabin, and Rachmaninoff.[9] Schoenberg's Five Pieces for Orchestra also received its first performance (the composer not being present);[90] during rehearsals, Wood urged his players, "Stick to it, gentlemen! This is nothing to what you'll have to play in 25 years' time". The critic Ernest Newman wrote after the performance: "It is not often that an English audience hisses the music it does not like, but a good third of the people at Queen's Hall last Tuesday permitted themselves that luxury after the performance of the five orchestral pieces of Schoenberg. Another third of the audience was only not hissing because it was laughing, and the remaining third seemed too puzzled either to laugh or to hiss; so that on the whole it does not look as if Schoenberg has so far made many friends in London."[91] However, when Wood invited Schoenberg himself to conduct the work's second British performance, on 17 January 1914, the composer was so delighted with the result, more appreciatively received than had been the premiere, that he congratulated Wood and the orchestra warmly: "I must say it was the first time since Gustav Mahler that I heard such music played again as a musician of culture demands."[92]

First World War and post-war

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Newman, Wood and Speyer discussed whether the Proms should continue as planned. They had by this time become an established institution,[n 11] and it was agreed to go ahead. However, anti-German feeling forced Speyer to leave the country and seek refuge in the US, and there was a campaign to ban all German music from concerts.[94] Newman put out a statement declaring that German music would be played as planned: "The greatest examples of Music and Art are world possessions and unassailable even by the prejudices and passions of the hour."[95] When Speyer left Britain, the music publishers Chappell's took on the responsibility for the Queen's Hall and its orchestra. The Proms continued throughout the war years, with fewer major new works than before, although there were nevertheless British premieres of pieces by Bartók, Stravinsky and Debussy. An historian of the Proms, Ateş Orga, wrote, "Concerts often had to be re-timed to coincide with the 'All Clear' between air raids. Falling bombs, shrapnel, anti-aircraft fire and the droning of Zeppelins were ever threatening. But [Wood] kept things on the go and in the end had a very real part to play in boosting morale."[96]

Towards the end of the war, Wood received an offer by which he was seriously tempted: the Boston Symphony Orchestra invited him to become its musical director.[97] He had been guest conductor of the Berlin and New York Philharmonic Orchestras,[98] but he regarded the Boston orchestra as the finest in the world.[17] Nonetheless, as he told Boult, "it was hard to refuse, but I felt it was a patriotic duty to remain in my own country, at the present moment."[99]

After the war, the Proms continued much as before. The second halves of concerts still featured piano-accompanied songs rather than serious classical music. Chappell's, having taken over sponsorship of the Proms and spent £35,000 keeping the Queen's Hall going during the war, wished to promote songs published by the company. The management of Chappell's were also less enthusiastic than Wood and Newman about promoting new orchestral works, most of which were not profitable.[100]

In 1921, Wood was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society, the first English conductor to receive the honour.[n 12] By now he was beginning to find his position as Britain's leading conductor under challenge from rising younger rivals. Thomas Beecham had been an increasingly influential figure since about 1910. He and Wood did not like one another, and each avoided mention of the other in his memoirs.[102]

Adrian Boult, who, at Wood's recommendation, took over some of his responsibilities at Birmingham in 1923, always admired and respected Wood.[103] Other younger conductors included men who had been members of Wood's orchestra, including Basil Cameron and Eugene Goossens.[104] Another protégé of Wood was Malcolm Sargent, who appeared at the Proms as a composer-conductor in 1921 and 1922.[105] Wood encouraged him to abandon thoughts of a career as a pianist and to concentrate on conducting.[106] Wood further showed his interest in the future of music by taking on the conductorship of the student orchestra at the Royal Academy of Music in 1923, rehearsing it twice a week, whenever possible, for the next twenty years. In the same year, he accepted the conductorship of the amateur Hull Philharmonic Orchestra, travelling three times a year until 1939 to rehearse and conduct its concerts.[107]

In 1925, Wood was invited to conduct four concerts for the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra at the Hollywood Bowl. Such was their success, both artistic and financial, that Wood was invited back, and conducted again the following year. In addition to a large number of English pieces, Wood programmed works by composers as diverse as Bach and Stravinsky. He again conducted there in 1934.[108]

BBC and the Proms

On his return to England from his first Hollywood trip, Wood found himself in the middle of a feud between the chairman of Chappell's, William Boosey, and the BBC. Boosey had conceived a passionate hostility to the broadcasting of music, fearing that it would lead to the end of live concerts. He attempted to prevent anyone who wished to perform at the Queen's Hall from broadcasting for the BBC. This affected many of the artists whom Wood and Newman needed for the Proms. The matter was unresolved when Newman died in 1926. Shortly afterwards, Boosey announced that Chappell's would no longer support concerts at the Queen's Hall.[109] The prospect that the Proms might not be able to continue caused widespread dismay, and there was a general welcome for the BBC's announcement that it would take over the running of the Proms, and would also run a winter series of symphony concerts at the Queen's Hall.[110]

The BBC regime brought immediate benefits. The use of the second half of concerts to promote Chappell's songs ceased, to be replaced by music chosen for its own excellence: on the first night under the BBC's control, the songs in the second half were by Schubert, Quilter and Parry rather than ballads from Chappell's.[111] For Wood, the greatest benefit was that the BBC gave him twice as much rehearsal time as he had previously enjoyed. He now had a daily rehearsal and extra rehearsals as needed.[112] He was also allowed extra players when large scores called for them, instead of having to rescore the work for the forces available.[112]

In 1929, Wood played a celebrated practical joke on musicologists and critics. "I got very fed up with them, always finding fault with any arrangement or orchestrations that I made ... 'spoiling the original' etc. etc.",[113] and so Wood passed off his own orchestration of Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D minor, as a transcription by a Russian composer called Paul Klenovsky.[n 13] In Wood's later account, the press and the BBC "fell into the trap and said the scoring was wonderful, Klenovsky had the real flare [sic] for true colour etc. – and performance after performance was given and asked for."[113] Wood kept the secret for five years before revealing the truth.[115] The press treated the deception as a great joke; The Times entered into the spirit of it with a jocular tribute to the lamented Klenovsky.[116][n 14]

As Wood's working life took a turn for the better, his domestic life started to deteriorate. During the early 1930s, he and his wife gradually became estranged, and their relationship ended in bitterness, with Muriel taking most of Wood's money and, for much of the time, living abroad.[n 15] She refused to divorce him.[119] The breach between Muriel and Wood also caused his estrangement from their daughters.[120] In 1934 he began a happy relationship with a widowed former pupil, Jessie Linton, who had sung for him frequently in the past under her professional name of Jessie Goldsack. One of Wood's players recalled, "She changed him. He had been badly dressed, awful clothes. Jessie got him a new evening suit, instead of the mouldy green one, and he flourished yellow gloves and a cigar ... he became human."[49] As Wood was not free to remarry, she changed her name by deed poll to "Lady Jessie Wood" and was generally assumed by the public to be Wood's wife.[121] In his memoirs, Wood mentioned neither his second marriage nor his subsequent relationship.[121][122]

In his later years, Wood came to be identified with the Proms rather than with the year-round concert season. Boult was appointed director of music at the BBC in 1930. In that capacity he strove to ensure that Wood was invited to conduct a fitting number of BBC symphony concerts outside the Prom season.[123] The BBC chose Wood for important collaborations with Bartók and Paul Hindemith,[n 16] and for the first British performance of Mahler's vast Symphony No. 8.[107] But Jacobs notes that, in the general concert repertory, Wood now had to compete against well-known foreign conductors such as Bruno Walter, Willem Mengelberg, and Arturo Toscanini, "in comparison with whom he was increasingly seen as a workhorse".[107]

Last years

In 1936, Wood was in charge of his final Sheffield festival. The choral works he conducted included the Verdi Requiem, Beethoven's Missa Solemnis, Berlioz' Te Deum, Walton's Belshazzar's Feast, and, in the presence of the composer, Rachmaninoff's The Bells.[126] The following year, Wood began planning for a grand concert to mark his fiftieth year as a conductor. The Royal Albert Hall was chosen as the venue, having a far larger capacity than the Queen's Hall. The concert was given on 5 October 1938. Rachmaninoff played the solo part in his Second Piano Concerto, and Vaughan Williams, at Wood's request, composed a short choral work for the occasion: the Serenade to Music for orchestra and 16 soloists. The other composers represented in the programme were Sullivan, Beethoven, Bach, Bax, Wagner, Handel and Elgar. The orchestra comprised players from the three London orchestras: the London Symphony, London Philharmonic and BBC Symphony Orchestras. The concert raised £9,000 for Wood's chosen charity, providing health care for musicians.[127] In the same year, Wood published his autobiography, My Life of Music.[107]

In September 1939, the Second World War broke out and the BBC immediately put into effect its contingency plans to move much of its broadcasting away from London to places thought less susceptible to bombing. Its musical activities, including the orchestra, moved to Bristol.[128] The BBC withdrew not only the players, but financial support from the Proms. Wood determined that the 1940 season would nevertheless go ahead. The Royal Philharmonic Society and a private entrepreneur, Keith Douglas, agreed to back an eight-week season, and the London Symphony Orchestra was engaged. The season was curtailed after four weeks, when intense bombing forced the Queen's Hall to close.[129] The last Prom given at the Queen's Hall was on 7 September 1940. In May 1941, the hall was destroyed by bombs.[130]

It was immediately agreed that the 1941 season of Proms should be held at the Albert Hall. It was twice the size of the Queen's Hall, with poor acoustics, but a six-week series was judged a success, and the Albert Hall remained the home of the Proms. Wood, aged seventy-two, was persuaded to have an associate conductor to relieve him of some of the burden. Basil Cameron undertook the task and remained a Prom conductor until his retirement, aged eighty, in 1964.[131] The BBC brought its symphony orchestra back to London and resumed its backing of the Proms in 1942; Boult joined Cameron as Wood's associate conductor during that season.[132] In early 1943, Wood's health deteriorated, and two days after the start of that year's season, he collapsed and was ordered to have a month in bed.[133] Despite wartime vicissitudes, the 1943 season sold nearly 250,000 tickets, with an average audience of about 4,000 – many more than could have fitted into the Queen's Hall.[134]

Despite his age and the difficulties of wartime travel, Wood insisted on going to provincial cities to conduct – as much, according to Jacobs, to help the local orchestras survive as to gratify audiences.[107] His final season was in 1944. The season began well with Wood in good form, but after three weeks raids by the devastating new German flying bombs caused the government to order the closure of places of entertainment.[135] The Proms were immediately relocated to Bedford some 50 miles (80 km) away, where Wood continued to conduct. He was taken ill in early August and was unable to conduct the fiftieth anniversary Prom on 10 August; he was forbidden by his doctor even to listen to its broadcast. Wood died just over a week later on 19 August at Hitchin Hospital in Hitchin, Hertfordshire;[136] his funeral service was held in the town at St Mary's church,[137] and his ashes were interred in the Musicians' Chapel of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate.[138]

His arrangement of the national anthem was continued for the Last Night of the Proms until 2009, when Benjamin Britten’s arrangement replaced it in 2010. In 2022, the American Philadelphia Orchestra played Wood's arrangement of the national anthem out of respect for the recently deceased Queen Elizabeth II. Wood’s arrangement was bought back in 2023.

Recordings

Wood's recording career began in 1908, when he accompanied his wife Olga in "Farewell, forests" by Tchaikovsky, for the Gramophone and Typewriter Company, better known as His Master's Voice or HMV. They made eight other records together for HMV over the next two years.[139] After Olga's death, Wood signed a contract with HMV's rival, Columbia, for whom he made a series of discs between 1915 and 1917 with the singer Clara Butt, including excerpts from Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius.[140]

Between 1915 and 1925, he conducted 65 recordings for Columbia using the early acoustic recording process, including many discs of Wagner excerpts and a truncated version of Elgar's Violin Concerto with Albert Sammons as soloist.[141] When the microphone and electrical recording were introduced in 1925, Wood re-recorded the Elgar concerto, with Sammons, and made 36 other discs for Columbia over the next nine years.[142] The 1929 recording of the Elgar concerto has been reissued on compact disc and is well regarded by some critics.[n 17]

Wood was wooed from Columbia by the young Decca company in 1935. For Decca he conducted 23 recordings over the next two years, including Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, Elgar's Enigma Variations and Vaughan Williams's A London Symphony.[144] In 1938 he returned to Columbia, for whom his five new recordings included the Serenade to Music with the 16 original singers, a few days after the premiere, and his own Fantasia on British Sea Songs.[145]

Wood's recordings did not remain in the catalogues long after his death. The Record Guide, 1956, lists none of his records.[146] A few of his recordings have subsequently been reissued on compact disc, including the Decca and Columbia Vaughan Williams recordings from 1936 and 1938.[147]

Premieres

In Jacobs's 1994 biography, the list of premieres conducted by Wood extends to 18 pages.[148] His world premieres included Frank Bridge's The Sea; Britten's Piano Concerto; Delius's A Song Before Sunrise, A Song of Summer, and Idyll; Elgar's The Wand of Youth Suite No. 1, Sospiri and the 4th and 5th Pomp and Circumstance Marches; and Vaughan Williams's Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1, Flos Campi and Serenade to Music.[67]

Wood's UK premieres included Bartók's Dance Suite; Chabrier's Joyeuse marche; Copland's Billy the Kid; Debussy's Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune and Ibéria; Hindemith's Kammermusik 2 and 5; Janáček's Sinfonietta, Taras Bulba and Glagolitic Mass; Kodály's Dances from Galanta; Mahler's Symphonies Nos. 4, 7 and 8, and Das Lied von der Erde; Prokofiev's Piano Concerto No. 1 and Violin Concerto No. 2; Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No 1; Ravel's Ma mère l'oye, Rapsodie espagnole, La valse and Piano Concerto in D; Rimsky-Korsakov's Capriccio Espagnol, Scheherazade, and Symphony No. 2; Saint-Saëns's The Carnival of the Animals; Schumann's Konzertstück for four horns and orchestra; Shostakovich's Piano Concerto No. 1 and Symphonies Nos. 7 and 8; Sibelius's Symphonies Nos. 1, 6 and 7, Violin Concerto, Karelia Suite, and Tapiola; Richard Strauss's Symphonia Domestica; Stravinsky's The Firebird (suite); Tchaikovsky's Manfred Symphony and Nutcracker Suite; and Webern's Passacaglia.[67]

Honours, memorials and reputation

In addition to the knighthood bestowed in 1911, Wood's state honours were his appointments as Companion of Honour in the 1944 King's Birthday Honours List, to the Order of the Crown (Belgium; 1920), and Officer of the Legion of Honour (France; 1926). He received honorary doctorates from five English universities and was a fellow of both the Royal Academy of Music (1920) and the Royal College of Music (1923).[149] In March 1963, The Henry Wood Concert Society (in association with The Henry Wood Memorial Trust) presented The Henry Wood Memorial Concert. The concert was held at the Royal Albert Hall, London and conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent in the presence of H.R.H. The Duchess of Gloucester.

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_847582.jpg.webp)

Jacobs lists 26 compositions dedicated to Wood, including, in addition to the Vaughan Williams Serenade to Music, works by Elgar, Delius, Bax, Marcel Dupré and Walton.[149] The Poet Laureate, John Masefield, composed a poem of six verses in his honour, entitled "Sir Henry Wood", often referred to by its first line, "Where does the uttered music go?". Walton set it to music as an anthem for mixed choir; it received its first performance on 26 April 1946 at St Sepulchre's, on the occasion of a ceremony unveiling a memorial stained-glass window in Wood's honour.[150]

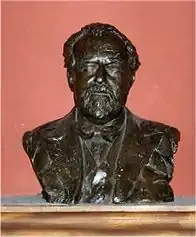

Wood is commemorated in the name of the Henry Wood Hall, the deconsecrated Holy Trinity Church in Southwark, which was converted to a rehearsal and recording venue in 1975.[151] His bust stands upstage centre in the Royal Albert Hall during the whole of each Prom season, decorated by a chaplet on the Last Night of the Proms. His collection of 2,800 orchestral scores and 1,920 sets of parts is now in the library of the Royal Academy of Music.[152] For the Academy he also established the Henry Wood Fund, giving financial aid to students.[8] The University of Strathclyde named a building at its Jordanhill campus after him.[153] His best-known memorial is the Proms, officially "the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts",[154] but universally referred to by the informal short version.[n 18]

His biographer Arthur Jacobs wrote of Wood:

His orchestral players affectionately nicknamed him "Timber" – more than a play on his name, since it seemed to represent his reliability too. His tally of first performances, or first performances in Britain, was heroic: at least 717 works by 357 composers. Greatness as measured by finesse of execution may not be his, particularly in his limited legacy of recordings, but he remains one of the most remarkable musicians Britain has produced.[16]

Writings

- Wood, Henry (26 May 1904). "Why I became a Conductor". The Musical Leader and Concert Goer. Chicago: Musical Leader Pub. Co.

- —— (1924). "Orchestral Colour and Values". In Hull, Arthur Eaglefield (ed.). A Dictionary of Modern Music and Musicians. London: J.M. Dent and Sons. OCLC 162576291.

- —— (1927–1928). The Gentle Art of Singing. Vol. Four volumes. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 155891475.

- —— (1938). My Life of Music. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd. OCLC 2600343.

- —— (1945). About Conducting. London: Sylvan Press. OCLC 717026319.

Notes and references

Notes

- According to Wood, his father was urged to become a professional singer by the conductor Sir Michael Costa and others.[2]

- Two shillings and sixpence: in decimal coinage, 12½ pence. In terms of average earnings, this equates to more than £65 in current values.[6]

- In 1911 Wood gave an exhibition of fifty sketches in oil at the Piccadilly Arcade Gallery, raising £200 in aid of the Queen's Hall Orchestra Endowment Fund.[8][9]

- Wood (p. 29) lists Garcia as among his professors, but Jacobs (p. 13) notes that Wood's name does not appear among the choir lists in which Garcia's pupils all appeared.

- Ten shillings and sixpence: 52½ pence in decimal terms; in 2009 values somewhere between £40 (based on retail prices) and £275 (based on average earnings).[6] Jacobs (p. 19) suggests that Wood may have exaggerated his fee when recalling it in his memoirs.

- George Bernard Shaw, in a long review in The World, commented on all the principal singers, the costumes, scenery and choreography, but did not mention the conductor.[25]

- In decimal coinage, respectively 5, 10, 15 and 25 pence: the equivalent of approximately £4 to £20 in terms of 2009 retail prices. Tickets for formal symphony concerts at the time cost up to five times as much.[6]

- In his memoirs Wood refers to her as "Princess Olga Ouroussoff", but according to Jacobs (p. 59) she was entitled to neither the rank nor the surname, although her mother was Princess Sofiya Urusova

- In 2002 and 2003, the Fantasia was performed "with additional Songs arranged by John Wilson, Stephen Jackson (chorusmaster of the BBC Symphony Orchestra) and Percy Grainger";[77] in 2004 "with additional Songs arranged by Stephen Jackson";[78] and in 2005, 2006 and 2007 with "extra Songs arranged by Bob Chilcott".[79]

- In his memoirs, Wood does not say where or for how long.

- Although Wood himself did not generally use the term "the Proms", it was common currency by now even in the more formal newspapers. It was used in The Observer and The Musical Times in 1912. The Times and The Manchester Guardian used the term from 1918 and 1923 respectively.[93] Even Wood used the term when referring to the Last Night of the Proms, which he called "the Last Prom of the Season".[80]

- Wood was only the second conductor of any nationality to receive the honour, the first being Hans von Bülow in 1873. Wood received the award four years before it was given to Delius and Elgar (1925). The next conductor to receive the medal was Sir Thomas Beecham (1928).[101]

- Cox (p. 102) states that there had been a real "Paul Klenovsky", a pupil of Glazunov who died young. Jacobs (p. 232) states that no such composer ever existed, although a Russian composer called Nicolai Klenovsky died in 1915. The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians supports the latter statement.[114]

- Later, The Times's music critic (anonymous, but presumed to be Frank Howes, the paper's music critic at the time) was less forgiving than his colleagues. Though his predecessor had called the supposed Klenovsky work "superlatively well done",[117] Howes described it, once Wood's authorship was known, as "monstrous and inexculpable".[118]

- After the marital split, Muriel Wood lived in Japan (her brother was British consul in Nagasaki), China and New Zealand. She did not return to England until after Wood's death.[107]

- At BBC symphony concerts, Wood conducted Hindemith's Viola Concerto, with the composer as soloist, and his oratorio Das Unaufhörlich;[124] and Bartók's Piano Concerto No 1 with the composer as soloist.[125] Wood also programmed their music during Proms seasons.

- The recording by Sammons and Wood was chosen in preference to all others by the reviewer Ian Burnside on BBC Radio 3's "Building a Library" feature in July 1999.[143]

- The histories of the concerts by Cox and Orga both use the short form in their titles.

References

- Jacobs, p. 4

- Wood, p. 17

- Wood, p. 13

- Jacobs, p. 6

- Wood, p. 17 and Jacobs, p. 6

- Williamson, Samuel H., "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present", MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 16 November 2010

- Jacobs, p. 10

- Herbage, Julian, "Wood, Sir Henry Joseph", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography archive, 1959. Retrieved 14 November 2010 (subscription required)

- Cox, p. 56

- Wood, p. 29

- Jacobs, p. 13

- "Occasional Notes", The Musical Times, November 1927, p. 1007–08

- Wood, p. 36

- Wood, p. 39

- Jacobs, p. 14

- Jacobs, Arthur, "Wood, Sir Henry J." Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 17 October 2010 (subscription required)

- "Mr. Henry J. Wood", Musical Opinion & Music Trade Review, March 1899, pp. 389–90

- Jacobs, p. 329

- Jacobs, pp. 3 and 17

- Wood, pp. 53–56 and Jacobs, pp. 19–20

- Elkin, Robert, "Henry J. Wood: Organist, Accompanist, Opera Conductor, and Composer", The Musical Times, August 1960, pp. 488–90

- Wood, pp. 58–60 and Jacobs, pp. 21–22

- Wood, p. 59

- Jacobs, p. 24

- Laurence, pp. 718–21

- Jacobs, p. 26

- The Lady Slavey - British Musical Theatre website

- J. P. Wearing, The London Stage 1890-1899: A Calendar of Productions, Performers, and Personnel, Rowman & Littlefield (2014) - Google Books pg. 228

- Henry Wood and The Lady Slavey (1894) - Museum of Music History

- Jacobs, p. 27

- Jacobs, pp. 30–32

- Elkin, pp. 25–26

- Elkin, p. 26

- Orga, p. 44

- Orga, p. 57

- Jacobs, p. 46

- Orga, p. 55

- Elkin, p. 25

- Jacobs, p. 34

- Jacobs, p. 38

- Cox, p. 33

- Cox, p. 34

- Jacobs, p. 45

- Cox, p. 35; and Orga, p. 61

- Cox, p. 35

- Wood, p. 84

- Cole, Hugo, "Sullivan without Gilbert", The Guardian, 29 July 1971, p. 8

- Shore, p. 189

- Previn, p. 160

- Shore, p. 200 and Wood, p. 96

- Wood, pp. 96–97

- Wood, p. 100; and Boult, Adrian, "Stereo Strings", The Musical Times, April 1973, p. 378

- Wood, p. 86

- Wood, p. 93

- Cox, p. 38

- Boult, p. 181

- Elkin, p. 144; and Jacobs, p. 56

- Jacobs, p. 62

- Jacobs, p. 59

- Jacobs, p. 67

- Cox, pp. 42–43

- Jacobs, p. 79, quoting, Otto Lessman in Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung

- Cox, p. 44

- Jacobs, pp. 62–63

- Jacobs, p. 43

- Jacobs, pp. 33–34

- Jacobs, pp. 441–61

- Jacobs, p. 102

- Levien, John Mewburn, quoted in Reid (1961), p. 50

- Morrison, p. 11

- Morrison, p. 24

- Wood, p. 101

- Jacobs, p. 131

- "Future of Music: Interview with Sir Henry Wood", The Observer, 2 June 1918, p. 7

- "Sir Henry Wood Will Stay", The Musical Herald, July 1918, p. 207

- Cox, pp. 31–32; and Orga, pp. 78–80

- "Fantasia on British Sea Songs (with additional Songs arranged by John Wilson, Stephen Jackson and Percy Grainger)", Proms Archive, BBC. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- "Fantasia on British Sea Songs (with additional Songs arranged by Stephen Jackson)", Proms Archive, BBC. Retrieved 19 November 2010

- "Fantasia on British Sea Songs (with additional Songs arranged by Bob Chilcott)", Proms Archive, BBC. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- Wood, p. 192

- Jacobs, pp. 173 and 434–35

- Jacobs, p. 111

- Jacobs, p. 116

- Jacobs, p. 117; and Blom, Eric, "A Fauré Memorial Concert", The Manchester Guardian, 10 June 1925, p. 12

- Jacobs, p. 129

- Cox, p. 55

- Jacobs, p. 123

- "Handel's Messiah and Applause", The Musical Times, December 1902, p. 826; and Jacobs, p. 132

- "The Autumn Music Festivals", The Manchester Guardian, 8 August 1911, p. 10

- Jacob, p. 137

- Newman, Ernest, "The Case of Arnold Schoenberg", The Nation, 7 September 1912, p. 830, quoted in Lambourn, David, "Henry Wood and Schoenberg", The Musical Times, August 1987, pp. 422–427

- Letter dated 23 January 1914, quoted in Lambourn, David, "Henry Wood and Schoenberg", The Musical Times, August 1987, p. 426

- "Covent Garden Opera – Le Lac Des Cygnes", The Observer, 28 July 1912, p. 7; "London Concerts", The Musical Times, December 1912 pp. 804–07; "The Promenade Concerts – Successful Opening of the Season", The Times, 12 August 1918, p. 9; and Newman, Ernest, "The Week in Music", The Manchester Guardian, 2 August 1923, p. 5

- Cox, pp. 64–65

- Cox, p. 65

- Orga, p. 88

- Orga, p. 87

- Jacobs pp. 65, 95

- Moore, p. 31

- Jacobs, p. 171

- "List of Gold Medal holders" Royal Philharmonic Society. Retrieved 21 November 2010

- Jacobs, p. 118

- Kennedy, p. 90

- Jacobs, p. 132

- Reid (1968), pp. 101, 105

- Wood, p. 317

- Jacobs Arthur, "Wood, Sir Henry Joseph (1869–1944)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 17 October 2010

- Jacobs, pp. 203–06

- Cox, p. 83

- Orga, pp. 93–94

- Cox, p. 87

- Cox, p. 88

- Jacobs, p. 232

- Brown, David, "Klenovsky, Nikolay Semyonovich," Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 22 November 2010 (subscription required) and "Klenovsky, Paul", Oxford Dictionary of Music, Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 22 November 2010 (subscription required)

- "'Paul Klenovsky' a Musical Hoax by Sir Henry Wood", The Times, 4 September 1934, p. 10

- "The Late Paul Klenovsky", The Times, 5 September 1934, p. 13

- "Promenade Concerts", The Times, 6 October 1930, p. 12

- "Sir H. Wood Memorial Concert", The Times, 5 March 1945, p. 8

- Jacobs, pp. 262–70 and 278

- Jacobs, p. 269

- Jacobs, pp. 265–71

- Wood, index pp. 376 and 384

- Kennedy, pp. 140–41; and Jacobs, p. 308

- "B.B.C. Symphony Orchestra: Hindemith's Viola Concerto", The Times, 23 November 1929, p. 10 and "Music This Week: An Oratorio by Hindemith", The Times, 20 March 1933, p. 10

- "Broadcasting, The Programmes, Sir Henry Wood at Queen's Hall", The Times, 14 February 1930, p. 22

- Jacobs, pp. 302–03

- Jacobs, pp. 311–14 and 329–30

- Cox, p. 110

- Cox, p. 116

- Elkin, p. 129

- Cox, pp. 122 and 208–09

- Cox, p. 123

- Cox, p. 124

- Cox, p. 126

- Orga, p. 120

- Orga, p. 121

- "BBC Proms 2010 Sir Henry's Hoard", BBC Press Office, September 2010

- 20th-Century Church History Archived 16 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine St Sepulchre-without-Newgate. Retrieved 1 January 2011

- Jacobs, p. 425

- Jacobs, p. 426

- Jacobs, pp. 426–28

- Jacobs, pp. 428–29

- "First Choice", Building a Library, BBC Radio 3. Retrieved 21 November 2010

- Jacobs, pp. 429–30

- Jacobs, p. 430

- Sackville-West, index, p. 957

- Dutton Vocalion CD (2001), catalogue number CDBP 9707

- Jacobs, pp. 442–61

- Jacobs, p. 465

- "Where does the uttered Music go?" Archived 21 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, WilliamWalton.net. Retrieved 21 November 2010

- "History", Henry Wood Hall. Retrieved 20 November 2010

- "Library", Royal Academy of Music. Retrieved 21 November 2010; Herbage, Julian, "Wood, Sir Henry Joseph", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography archive, 1959. Retrieved 14 November 2010 (subscription required); and Cox, p. 56

- "Sir Henry Wood Building," Archived 5 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine University of Strathclyde. Retrieved 1 January 2011

- Jacobs, pp. 127–28

Sources

- Boult, Adrian (1973). My Own Trumpet. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-02445-5.

- Cox, David (1980). The Henry Wood Proms. London: BBC. ISBN 0-563-17697-0.

- Elkin, Robert (1944). Queen's Hall, 1893–1941. London: Rider. OCLC 636583612.

- Jacobs, Arthur (1994). Henry J. Wood: Maker of the Proms. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-69340-6.

- Kennedy, Michael (1987). Adrian Boult. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-333-48752-4.

- Laurence, Dan H., ed. (1989). Shaw's Music – The Complete Music Criticism of Bernard Shaw, Volume 2. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 0-370-31271-6.

- Moore, Jerrold Northrop, ed. (1979). Music and Friends: Letters to Adrian Boult. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-10178-6.

- Morrison, Richard (2004). Orchestra – The LSO. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-21584-X.

- Orga, Ateş (1974). The Proms. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-6679-3.

- Previn, André, ed. (1979). Orchestra. London: Macdonald and Janes. ISBN 0-354-04420-6.

- Reid, Charles (1968). Malcolm Sargent. London: Hamish Hamilton. OCLC 603636443.

- Reid, Charles (1961). Thomas Beecham. London: Victor Gollancz. OCLC 52025268.

- Sackville-West, Edward; Desmond Shawe-Taylor (1956). The Record Guide. London: Collins. OCLC 500373060.

- Shore, Bernard (1938). The Orchestra Speaks. London: Longmans. OCLC 499119110.

- Wood, Henry J. (1938). My Life of Music. London: Victor Gollancz. OCLC 30533927.

External links

- Henry Wood's Proms appearances as performer and as composer, listed on BBC Proms website at www.bbc.co.uk

- Concert Programmes 1790–1914 at www.cph.rcm.ac.uk

- Two digitally restored recordings conducted by Sir Henry Wood