South Eastern Highlands

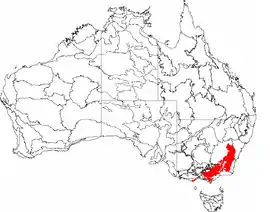

The South Eastern Highlands is an interim Australian bioregion in eastern Australia, that spans parts of the states and territories of New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, and Victoria. The bioregion comprises 8,375,961 hectares (20,697,450 acres) and is approximately 3,860 kilometres (2,400 mi) long. The Australian Alps as well as the South West Slopes bound the region from the south and west; and to the northeast, the Sydney Basin bioregion, as well as the bioregion of the South East Corner, to the east.[1]

| South Eastern Highlands Australia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The view across Namadgi National Park within the Australian Capital Territory, located within the South Eastern Highlands bioregion. | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Area | 83,760 km2 (32,339.9 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

In addition to Canberra, several regional cities make up part of the bioregion such as Lithgow and Bathurst in the north, Queanbeyan and Yass in the centre, Goulburn and Bowral in the east, and the towns of Bombala and Delegate in the south. The South Eastern Highlands are an important source of gold, copper, tin, oil, and natural gas.

The region is known for the mountains and plateaus that parallel the east and southeast territory of Australia. This forms the Continental Divide, which includes Tasmania, and rises to Mount Kosciuszko, continental Australia’s highest peak at 2,228 metres (7,310 ft) tall.

Regional history

The South Eastern Highlands have been occupied by many groups of people within history. The region is divided into different groups. The Ngunawal and Gandangara groups occupied the northern part. Ngarigo groups lived in the southern and center of the region. The Walbanga group also lived in the center along with the Ngarigo group. In the western part of the highlands, a group named the Wagal occupied that part of the highlands.[1]

The South Eastern Highlands have many resources that provide food for the groups that live there. Some of the foods that the people relied on were the indefinite quantity of vegetables that were available to the people. The highlands also provided the people yam, daisy, and wattle seeds that were very useful during the months of July and August. Other resources were fish, crayfish, possums, and other larger animals that people could hunt. This really gave occupiers a reason to stay in the highlands because they had everything they needed to survive.

During the 1820s, the Europeans began to settle in the South Eastern Highlands because they saw potential in the land. While the Europeans settled in the highlands, this disrupted the lifestyle of the original people living there and their resources. Their resources were being badly affected by this. There were reports on how there was a shortage of water which would later effect the animals that rely on this resource. This change affected the people because now there was a shortage of water and animals such as fish and animals that would constantly come and drink water would eventually die out. Having the Europeans settle in on this land not only affected the resources of the people, but started to spread dangerous diseases to the population. Some of the diseases that were spread were the influenza epidemic and syphilis.

Although there were many damaging effects European settlement in the highlands, there were a lot of positive things that came out of this. One of the positive things was that the Europeans discovered copper in the bioregion which later became a place for copper mining. They also found gold, silver, antimony and zinc which really helped their economy. Miners who would mine in the area would grow crops such as apple, cherry and plum trees. This gave people more resources and benefited them a lot.

Landform

Topography

The South Eastern Highlands Bioregion encompasses the ranges of the Great Dividing Range that are geographically beneath the southwest Australian Alps. It spreads to the Great Escarpment in the east and to the western slopes of the inland drainage basins, and continues into Victoria.[2]

Geology

The Highlands are a portion of the Lachlan Fold Belt that goes through the eastern states as a sequence of metamorphosed Ordovician to Devonian sandstones, shales and volcanic rocks, which imposed by many granite bodies and distorted by four episodes of folding, faulting and uplift. North to south is the general structural trend in this bioregion.

The Early Ordovician serpentinite rocks running from Gundagai past Tumut into the Snowy Mountains are the oldest. These uncommon rocks were created in abyssal environments and were surfaced against the edge of Australia when a part of sea floor and an island arc closed.

The Ordovician Molong Volcanic Arc that spreads from the northern end of the bioregion to Kiandra is the greatest island arc environment. This comprises diverse sediment placed from massive submarine landslides, also interblended with quartz sandstone and basaltic tuffs. In the Devonian, the region was open sea. The region continued collecting fine sediment now denoted by shales, sandstone and volcanic sediments in a series of parallel troughs such as at Tumut, Hill End, and from Captains Flat to Goulburn.

The Eastern Highlands encompass a sequence of mountains in the south crowned by Mount Kosciuszko and volcanic plugs, ash domes and flow remainders further north.[3] Volcanic activity was extensive and there are enormous areas of related river sands and gravels in the mid-Shoalhaven valley, which are in the Cenozoic. Mount Canobolas was a chief volcano 50 kilometres (31 mi) in diameter, now weather-beaten to disclose more than fifty leftover vents, plugs, dykes, and trachyte domes.

The Monaro is where the principle lava fields are, and 65 eruption centers have been recognized there. They have been dated as 34-55 million years old. The Highlands are very rich in minerals, and contain most of Australia’s coalfields also.[4] In the Snowy Mountains, at Kiandra more precisely, an 18- to 20‑million-year-old hill top river gravels was driven for gold.

The leading structures of the bioregion are plateau remainders, granite basins with protruding ridges molded on contact metamorphic rocks and the western ramp classifying to the South Western Slopes. Streams going through the bioregion are intensely rooted with only a few terrace geographies, and valleys are really narrow. The landforms that are seen today are due to the lengthy, constant progressions of movement and erosion over millions of years, which escalate into a variation of landscapes across Australia. These are continuing to experience modification as the continent moves north.

Climate

Climate varies greatly across the South Eastern Highlands because of the topographic variation and its effect on atmospheric pressure, light, wind, and rain. It mostly has a temperate climate, with warm to mild summers, cool to cold winters and a largely uniform rainfall pattern tending to wetter winters in the south and west. The mean annual temperature is between 6–16 °C (43–61 °F). There are usually a lot of upland gales. The strongest winds are usually in the afternoons.[5]

Mean annual rainfall ranges from 500 millimetres (20 in) on the rain-shadowed Monaro to well over 2,000 millimetres (79 in) on the Snowy Mountains; most areas receive around 800 millimetres (31 in) of annual rainfall. There is more cloud cover in the areas of higher altitude, especially west of the divide where rainfall is greater across the year. In the central NSW highlands, snow occurs with some regularity above about 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) but is uncommon below 800 metres (2,600 ft); however in Victoria and southern NSW, snowfalls are common below this altitude, sometimes falling to 500 metres (1,600 ft) or much lower (sea-level snow has been known to fall on the southern Victorian coastline). Eastern parts of the region are sheltered from the prevailing westerlies, making winters and springs significantly warmer and drier compared to regions in the South West Slopes.

Biodiversity

Both soils and vegetation are affected by the temperature through the distribution of species, which can be observed through sequences in the frost hollows. The vegetation consists of yellow box, red box, and Blakely’s red gum. Areas of white box is located in the lower areas, where Red Stringybark, peppermint, and white gum dominate hills in the west. Brown barrel is common in the east, and river oak is along the main streams. In the highest places, throughout the cold air pockets, are patches of snow gum. Throughout the swamps on the Boyd Plateau, is where tea tree is located.[6]

Granite-derived soils support apple box, yellow box, and some white box. Rocky crops support patches of black cypress pine. Where cold plateaus, with open woodlands support black sallee. River oak is also located along streams. Extensive grasslands are common on the driest plains of the Monaro, covering with snow grass, kangaroo and wallaby grass. Sandy soils have peppermint, snappy gum, and forest oak. There are 88 flora species in the bioregion. 36 are endangered, 50 are vulnerable, and 2, Stemmacantha and Gualium are extinct. There are 88 fauna species in the bioregion. 25 are endangered, 63 vulnerable. The small honeyeaters are declining due to fragmented landscape. Decay over decades will cause the noisy miner, Australian magpie, and grey butcherbird are expected to decay in the landscape over time.

Only seven percent of all significant fauna species were of introduced taxa. Suggesting there has been little change in the high quality areas, but that gradual environmental degradation is occurring across the broader landscape.

There are no significant wetlands recorded in this part of the South Eastern Highlands bioregion. A number of wetlands in the bioregion are regarded as nationally important and listed in the Directory of important Wetlands in Australia. These wetlands are exposed to many threats of exotic weed invasion, feral animals, grazing pressure, sedimentation and changed water regimes. Driving and camping can also be a threat to the biodiversity of wetlands in the bioregion.

Sub-regions

In the IBRA system, the bioregion has the code of (SEH), and it has sixteen sub-regions:[7]

| IBRA regions and subregions: IBRA7 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBRA subregion | IBRA code | Area | ||

| ha | acres | |||

| Highlands-Southern Fall | SEH01 | 1,196,334 | 2,956,210 | |

| Highlands-Northern Fall | SEH02 | 1,415,806 | 3,498,530 | |

| Otway Ranges | SEH03 | 149,857 | 370,300 | |

| Strzelecki Ranges | SEH04 | 342,045 | 845,210 | |

| Murrumbateman | SEH06 | 630,454 | 1,557,890 | |

| Bungonia | SEH07 | 431,185 | 1,065,480 | |

| Kanangra | SEH08 | 131,310 | 324,500 | |

| Crookwell | SEH09 | 466,523 | 1,152,800 | |

| Oberon | SEH10 | 293,164 | 724,420 | |

| Bathurst | SEH11 | 161,486 | 399,040 | |

| Orange | SEH12 | 284,172 | 702,200 | |

| Hill End | SEH13 | 504,377 | 1,246,340 | |

| Bondo | SEH14 | 541,990 | 1,339,300 | |

| Kybeyan-Gourock | SEH15 | 479,221 | 1,184,180 | |

| Monaro | SEH16 | 1,267,543 | 3,132,170 | |

| Capertee Uplands | SEH17 | 80,494 | 198,910 | |

References

- "South Eastern Highlands Bioregion". Environment & Heritage. Government of New South Wales. 27 February 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "South Eastern Highlands - landform". Environment & Heritage. NSW Government. 27 February 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "Australian Landforms and their History". Geoscience Australia. Australian Government. 18 November 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "Eastern Highlands". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Infoplease. 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "South Eastern Highlands - climate". Environment & Heritage. NSW Government. 27 February 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "South Eastern Highlands - biodiversity". Environment & Heritage. NSW Government. 27 February 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "Subregions and codes: Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA7) Codes" (PDF). Department of the Environment and Energy. Australian Government. Retrieved 25 March 2018.