Corvée

Corvée (French: [kɔʁve] ⓘ) is a form of unpaid forced labour that is intermittent in nature, lasting for limited periods of time, typically only a certain number of days' work each year.

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of public works.[1] As such it represents a form of levy (taxation). Unlike other forms of levy, such as a tithe, a corvée does not require the population to have land, crops or cash.

The obligation for tenant farmers to perform corvée work for landlords on private landed estates was widespread throughout history before the Industrial Revolution. The term is most typically used in reference to medieval and early modern Europe, where work was often expected by a feudal landowner of their vassals, or by a monarch of their subjects.

The application of the term is not limited to feudal Europe; corvée has also existed in modern and ancient Egypt, ancient Sumer,[2] ancient Rome, China, Japan, the Incan civilization, Haiti under Henry I and under American occupation (1915–1934), and Portugal's African colonies until the mid-1960s. Forms of statute labour officially existed until the early 20th century in Canada[3][4] and the United States.

Etymology

The word corvée has its origins in Rome, and reached English via French. In the later Roman Empire the citizens performed opera publica in lieu of paying taxes; often it consisted of road and bridge work. Roman landlords could also demand a certain number of days' labour from their tenants, and from freedmen; in the latter case the work was called opera officialis. In medieval Europe, the tasks that serfs or villeins were required to perform on a yearly basis for their lords were called opera riga. Plowing and harvesting were principal activities to which this applied. In times of need, the lord could demand additional work called opera corrogata (Latin: corrogare, lit. 'to requisition'). This term evolved into coroatae, then corveiae, and finally corvée, and the meaning broadened to encompass both the regular and exceptional tasks. The word survives in modern usage, meaning any kind of inevitable or disagreeable chore.[5]

History

Egypt

From the Egyptian Old Kingdom (c. 2613 BC, the 4th Dynasty) onward, corvée contributed to government projects. During the times of the Nile River floods, it was used for construction projects such as pyramids, temples, quarries, canals, roads, and other works.

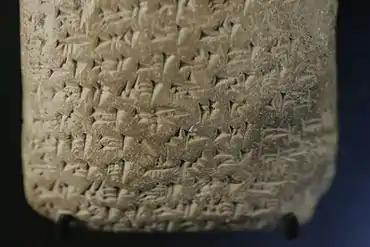

The 1350 BC Amarna letters, mostly addressed to the pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, have one short letter on the topic of corvée. Of the 382 Amarna letters, there is an undamaged letter from Biridiya of Megiddo entitled "Furnishing corvée workers".

Later, during the Ptolemaic dynasty, Ptolemy V in his Rosetta Stone Decree of 196 BC listed 22 accomplishments to be honored and ten rewards granted to him for the former. One of the shorter accomplishments, near the middle of the list, is:

He (pharaoh) decreed:—Behold, not is permitted to be pressed men of the sailors.[6]

The statement implies it was a common practice.

Until the late 19th century, many of the Egyptian Public Works, including the Suez Canal,[7] were built using corvée. Legally, the practice ended in Egypt after 1882, when the British Empire took control of the country and opposed forced labour on principle, but its abolition was postponed until Egypt had paid off its foreign debts. During the 19th century corvée had expanded into a national program. It was favoured for short-term projects such as building irrigation works and dams. However, Nile Delta landowners replaced it with cheap temporary labour recruited from Upper Egypt. As a result, it was used only in scattered locales, and even then there was peasant resistance. It began to disappear as Egypt modernized after 1860, and had fully vanished by the 1890s.[8]

Europe

Medieval agricultural corvée was not entirely unpaid. By custom the workers could expect small payments, often in the form of food and drink consumed on the spot. Corvée sometimes included military conscription, and the term is also occasionally used in a slightly divergent sense to mean forced requisition of military supplies; this most often took the form of cartage, a lord's right to demand wagons for military transport.

Because agricultural corvée tended to be demanded by the lord at the same time that the peasants needed to tend their own plots – e.g. at planting and harvest – it was an object of serious resentment. By the 16th century its use in agricultural settings was on the decline and it became increasingly replaced by paid labour. It nevertheless persisted in many areas of Europe until the French Revolution and beyond.[9]

Austria, the Holy Roman Empire, and Germany

Corvée, specifically socage, was essential to the feudal system of the Habsburg monarchy and later Austrian Empire, and most German states that belonged to the Holy Roman Empire. Farmers and peasants were obliged to do hard agricultural work for their nobility, typically six months of the year. When a cash economy became established, the duty was gradually replaced by the duty to pay taxes.

After the Thirty Years' War, the demand for corvée grew too high and the system became dysfunctional. Its official decline is linked to the abolition of serfdom by Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor and Habsburg ruler, in 1781. It continued to exist however, and was only abolished during the revolutions of 1848, along with the legal inequality between the nobility and common people.

Bohemia (or the Czech lands) was a part of the Holy Roman Empire as well as the Habsburg monarchy, and corvée was called robota in Czech. In Russian and other Slavic languages robota denotes any kind of work, but in Czech it specifically refers to unpaid unfree work, corvée or serf labour, or drudgery. The Czech word was imported to part of Germany where corvée was known as Robath, and into Hungarian as robot. The word robota was later used by Czech writer Karel Čapek, who after a recommendation by his brother Josef Čapek introduced the word robot for (originally anthropomorphic) machines that do unpaid work for their owners in his 1920 play R.U.R.

France

In France corvée existed until 4 August 1789, shortly after the beginning of the French Revolution, when it was abolished along with a number of other feudal privileges of the French landlords. At that time it was usually directed mainly towards improving the roads. It was greatly resented, and is considered an important cause of the Revolution. Counterrevolution revived corvée in France in 1824, 1836, and 1871, under the name prestation. Every able-bodied man had to give three days' labour or its money equivalent in order to vote. It also continued to exist under the seigneurial system in what had been New France, in British North America.

In 1866, during the French occupation of Mexico, the French Army under Marshal François Achille Bazaine set up a corvée system to provide labour for public works instead of a system of fines.[10]

Romanian principalities

In Romania, corvée was called clacă. Karl Marx described the corvée system of the Danubian Principalities as a pre-capitalist form of compulsory over-work. The labour the peasants needed for their own maintenance was distinctly separate from the work they supplied to the landowner (the boyar, or boier in Romanian) as surplus labour. The 14 days of labour due to the landowner – as prescribed by the corvée code in the Regulamentul Organic – actually amounted to 42 days, because the working day was considered the time required for the production of an average daily product, "and that average daily product is determined in so crafty a way that no Cyclops would be done with it in 24 hours."[11] The corvée code was supposed to abolish serfdom, but did not achieve anything toward this goal.

A land reform took place in 1864, after the Danubian Principalities unified and formed the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which abolished corvée and turned the peasants into free proprietors. The former owners were promised compensation, which was to be paid from a fund the peasants had to contribute to for 15 years. Besides the annual fee, the peasants also had to pay for the newly owned land, although at a price below market value. These debts made many peasants return to a life of semi-serfdom.

Russian Empire

In the Russian Tsardom and the Russian Empire there were a number of permanent corvées called tyaglyye povinnosti (Russian: тяглые повинности, lit. 'tax duties'), which included carriage corvée (подводная повинность, podvodnaya povinnost'), coachman corvée (ямская повинность, yamskaya povinnost'), and lodging corvée (постоялая повинность, postoyalaya povinnost'), among others.

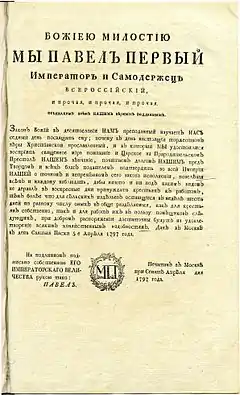

In the context of Russian history, the term corvée is also sometimes used to translate the terms barshchina (барщина) or boyarshchina (боярщина), which refer to the obligatory work that the Russian serfs performed for the pomeshchik (Russian landed nobility) on their land. While no official government regulation on the duration of barshchina labour existed, a 1797 ukase by Paul I of Russia described a barshchina of three days a week as normal and sufficient for the landowner's needs.

In the Black Earth Region, 70% to 77% of the serfs performed barshchina and the rest paid levies (obrok).[12]

Haiti

The independent Kingdom of Haiti based at Cap-Haïtien under Henri Christophe imposed a corvée system upon the common citizenry which was used for massive fortifications to protect against French invasion. Plantation owners could pay the government and have labourers work for them instead. This enabled the Kingdom of Haiti to maintain a stronger economic structure than the Republic of Haiti based in Port-au-Prince in the South under Alexandre Pétion which had a system of agrarian reform distributing land to the labourers.

After deploying to Haiti in 1915 as an expression of the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, the U.S. Armed Forces enforced a corvée system in the interest of making improvements to infrastructure.[13]

Imperial China

Imperial China had a system of conscripting labour from the public, equated to the Western corvée system by many historians. Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor, and following dynasties imposed it for public works like the Great Wall, the Grand Canal, and the system of national roads and highways. However, as the imposition was exorbitant and punishment for failure draconian, Qin Shi Huang was resented by the people and criticized by many historians. Corvée labour was effectively abolished following the Ming dynasty.[14]

Inca Empire and modern Peru

The Inca Empire levied tribute labour through a system called Mit'a which was perceived as a public service to the empire. At its height of efficiency, some subsistence farmers could be called to as many as 300 days of mit'a per year. The Spanish colonial rulers co-opted this system after the Spanish conquest of Peru to use natives as a source of forced labour on encomiendas and in silver mines. The Incan system that focused on public works found a comeback during the 1960s government of Fernando Belaúnde Terry as a federal effort, with positive effects on Peruvian infrastructure.

Remnants of the system are still found today in modern Peru, such as the Mink'a (Spanish: faena) communal work that is levied in Quechua communities in the Andes. An example is the campesino village of Ocra close to Cusco, where each adult is required to perform four days of unpaid labour per month on community projects.

India

Corvée-style labour (viṣṭi in Sanskrit) existed in ancient India and lasted until the early 20th century.[15] The practice is mentioned in the Mahabharata, where forced labourers are said to accompany the army. Manu said mechanics and artisans should be made to work for the king one day a month; other writers advocated for one day of work every fortnight (in all Indian lunar calendars, every month is divided into two fortnights, corresponding to the waxing and the waning moons). For poorer citizens, forced labour was seen as a way to pay their taxes since they could not pay ordinary taxes. Citizens, especially skilled workers, were sometimes made to both pay ordinary taxes and work for the state. If called to work, citizens could pay in cash or kind to discharge their obligations in some cases. In the Maurya and post-Maurya time period, forced labour had become a regular source of income for the state. Written evidence shows rulers granting lands and villages with and without the right to forced labour from workers of those lands.

Japan

A corvée-style system called soyōchō (租庸調) was found in pre-modern Japan. During the 1930s, it was common practice to import corvée labourers from both China and Korea to work in coal mines.[16] This practice continued until the end of World War II.

Madagascar

France annexed Madagascar as a colony in the late 19th century. Governor-General Joseph Gallieni implemented a hybrid corvée and poll tax system, partly for revenue, partly for labour resources as the French had just abolished slavery there, and partly to move away from a subsistence economy. The latter involved paying small amounts for the forced labour. This was one attempt by the colonial administration at a solution to the economic tensions that arose under colonialism. The problems were addressed in a way that was typical of colonialism which, along with the contemporary thinking behind it, is demonstrated in a 1938 work by Sonia E. Howe:[17]

There was the introduction of equitable taxation, so vital from the financial point of view; but also of such great political, moral and economic importance. It was the tangible proof of French authority having come to stay; it was the stimulus required to make an inherently lazy people work. Once they had learned to earn they would begin to spend, whereby commerce and industry would develop.

The corvée in its old form could not be continued, yet workmen were required both by the colonists, and by the Government for its vast schemes of public works. The General [Gallieni] therefore passed a temporary law, in which taxation and labour were combined, to be modified according to country, the people, and their mentality. Thus, for instance, every male among the Hovas, from the age of sixteen to sixty, had either to pay twenty-five francs a year, or give fifty days of labour of nine hours a day, for which he was to be paid twenty centimes, a sum sufficient to feed him. Exempted from taxation and labour were soldiers, militia, Government clerks, and any Hova who knew French, also all who had entered into a contract of labour with a colonist. Unfortunately, this latter clause lent itself to tremendous abuses. By paying a small sum to some European, who nominally engaged them, thousands bought their freedom from work and taxation by these fictitious contracts, to be free to continue their lazy, unprofitable existence. To this abuse an end had to be made.

The urgency of a sound fiscal system was of tremendous importance to carry out all the schemes for the welfare and development of the island, and this demanded a local budget. The goal to be kept in view was to make the colony, as soon as possible, self-supporting. This end the Governor-General succeeded in achieving within a few years.

The Philippines

The system of forced labour otherwise known as polo y servicios evolved within the framework of the encomienda system, introduced into the South American colonies by the Spanish government. Polo y servicios in the Spanish Philippines refers to 40 days' forced manual labour for men from 16 to 60 years of age; these workers built community structures such as churches. Exemption from polo was possible via paying the falla (corruption of the Spanish falta, meaning 'absence'), which was a daily fine of one and a half reales. In 1884, the required amount of labour was reduced to 15 days. The system was patterned after the repartimento system for forced labour in Spanish America.[18]

Portugal's African colonies

In Portuguese Africa (e.g. Mozambique), the Native Labour Regulations of 1899 stated that all able bodied men must work for six months of every year, and that "[t]hey have full liberty to choose the means through which to comply with this regulation, but if they do not comply in some way, the public authorities will force them to comply."[19]

Africans engaged in subsistence agriculture on their own small plots were considered unemployed. The forced labour was sometimes paid, but in cases of rule violations it was sometimes not – as punishment. The state benefited from the use of the labour for farming and infrastructure, by high income taxes on those who found work with private employers, and by selling corvée labour to South Africa. This system, called chibalo, was not abolished in Mozambique until 1962, and continued in some forms until the Carnation Revolution in 1974.

North America

Corvée was used in several states and provinces in North America especially for road maintenance, and this practice persisted to some degree in the United States and Canada. Its popularity with local governments gradually waned after the American Revolution with the increasing development of the monetary economy. After the American Civil War, some Southern states, with money in short supply, commuted taxing their inhabitants with obligations in the form of labour for public works, or let them pay a fee or tax to avoid it. The system proved unsuccessful because of the poor quality of work. In 1894, the Virginia Supreme Court ruled that corvée violated the state constitution,[20] and in 1913 Alabama became one of the last states to abolish it.[21]

Modern instances

The government of Myanmar is well known for its use of the corvée and has defended the practice in its official newspapers.[22]

In Bhutan, the driglam namzha calls for citizens to do work, such as dzong construction, in lieu of part of their tax obligation to the state.

In Rwanda, the centuries-old tradition of umuganda, or community labour, still continues, usually in the form of one Saturday a month when citizens are required to perform work.

Vietnam maintained corvée for females (ages 18–35) and males (ages 18–45) of 10 days yearly for public works at the discretion of the authorities. This was termed labour duty (Vietnamese: nghĩa vụ lao động).[23] However in 2006, the Standing Committee of the National Assembly voided the decree, effectively abolishing corvée in Vietnam.[24]

The British overseas territory of the Pitcairn Islands, which has a population of about 50 and no income or sales tax, has a system of public work whereby all able-bodied people are required to perform, when called upon, jobs such as road maintenance and repairs to public buildings.[25]

Since the mid-late 19th century, most countries have restricted corvée labour to conscription (military or civilian service), or prison labour.

See also

- Community service

- Penal labor in the United States

- Alternative civilian service

- Civil conscription

- Compulsory Border Guard Service

- Compulsory Fire Service

- Hand and hitch-up services

- Impressment

- Indenture

- Indigénat for instances of corvée in French colonial Africa

- Mit'a

- Nuribta (corvée letter to pharaoh)

- Serjeanty

- Socage

- Subbotnik

- Tax farming

- National Service

- Workfare

References

- "statute labour Definition". Britannica Money. 30 June 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Black, Jeremy (2004). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0.

- SUMMERBY-MURRAY, ROBERT (March 1999). "Statute labour on Ontario township roads, 1849-1948: Responding to a changing space economy". The Canadian Geographer. 43 (1): 36–52. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0064.1999.tb01359.x. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- Bob Aaron (8 December 2007). "Statute Labour Act could mean that some Ontario taxpayers must perform road work". Legal Tree. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- Mould, Michael (2011). The Routledge Dictionary of Cultural References in Modern French. New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-136-82573-6.

- Budge. The Rosetta Stone, pp. 138–139.

- Karabell, Zachary (2003). Parting the Desert: The creation of the Suez Canal. Alfred Knopf. pp. 113, 169–180. ISBN 0375408835.

- Nathan J. Brown, "Who abolished corvée labour in Egypt and why?" Past & Present 144 (1994): 116-137.

- In the Austro-Hungarian Empire, serfdom along with heavy forms of corvée were only abolished in 1848. Robert A. Kann, A history of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918, University of California Press, 1974, pp. 303–304.

- Jack A. Dabbs. The French Army in Mexico 1861–1867, p. 235.

- Marx, Karl (1967). Capital. A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 1. International Publishers. p. 228. ISBN 0717806219.

- Richard Pipes, Russia under the old regime, pp 147–48

- Paul Farmer, The Uses of Haiti (Common Courage Press: 1994)

- Myers, Ramon H.; Wang, Yeh-chien (16 December 2002), "Economic Developments, 1644–1800", The Cambridge History of China, Cambridge University Press, pp. 563–646, doi:10.1017/chol9780521243346.012, ISBN 9781139053532, retrieved 23 August 2022

- Maity, S. K. (1978). "Forced Labour in Ancient India". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 39: 147–151. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44139346.

- Richard J Samuels. Machiavelli's Children (Cornell University Press 2003)

- Sonia E. Howe, The Drama of Madagascar, pp. 331–32. Methuen & Co. London, 1938.

- Agoncillo, Teodoro (1990) [1960]. History of the Filipino People (8th ed.). Quezon City: Garotech. p. 83. ISBN 971-10-2415-2.

- Native Labour Regulations, section 1, 1899, Lisbon; in Gordon White, Robin Murray, and Christina White, Eds., Revolutionary Socialist Development in the Third World. 1983; Sussex, U.K.; Wheatsheaf Books. p.77.

- "Virginia as Analogue". H-Net Reviews. August 2004. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- M. G. Lay (1992). Motives and Management. Way of the World. p. 101. ISBN 9780813526911. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- Ending Forced Labour in Myanmar: Engaging a Pariah Regime Routledge, 2011

- "CSDLVBQPPL Bộ Tư pháp - Nghĩa vụ lao động công ích" [DBVBQPPL Ministry of Justice - Public service obligation]. Socialist Republic of Vietnam Ministry of Justice (in Vietnamese). 3 September 1999. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017.

- "1/1/2007: Bãi bỏ pháp lệnh lao động công ích". Báo điện tử Tiền Phong (in Vietnamese). 28 March 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- "Pitcairn Today". Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

Further reading

- See the chapter on "Corvées: valeur symbolique et poids économique" (5 articles on France, Germany, Italy, Spain and England), in: Bourin (Monique) ed., Pour une anthropologie du prélèvement seigneurial dans les campagnes médiévales (XIe–XIVe siècles): réalités et représentations paysannes, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2004, p. 271–381.

- The Rosetta Stone by E. A. Wallis Budge, (Dover Publications), c 1929, Dover edition (unabridged), c 1989.