Patani Kingdom

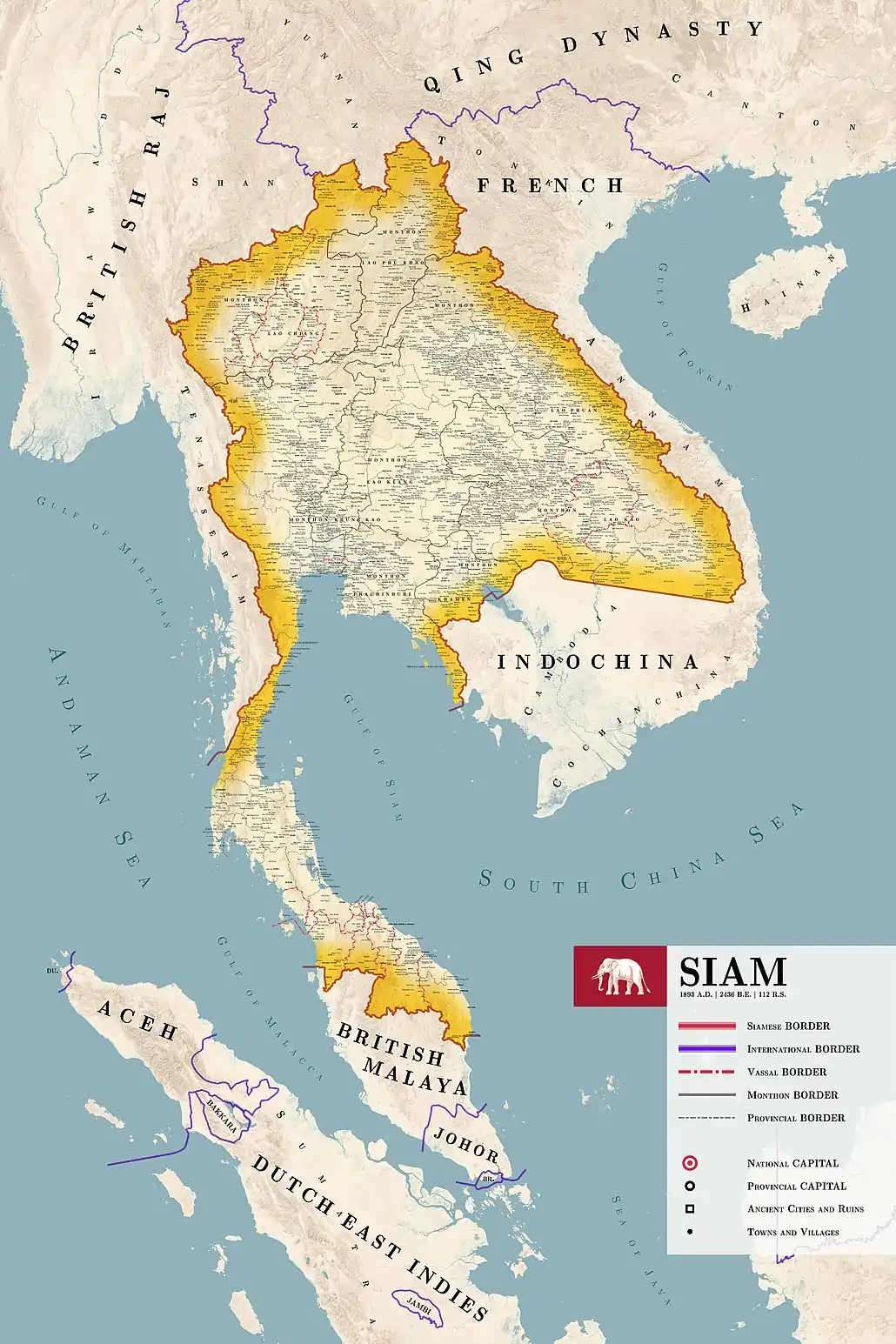

Patani, or the Sultanate of Patani (Jawi: كسلطانن ڤطاني) was a Malay sultanate in the historical Pattani Region. It covered approximately the area of the modern Thai provinces of Pattani, Yala, Narathiwat and part of the northern modern-day Malaysian state of Kelantan. The 2nd–15th century state of Langkasuka and 6–7th century state of Pan Pan may or may not have been related.

Sultanate of Patani كسلطانن ڤطاني Kesultanan Pattani | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1457?–1902 | |||||||||||

Map of the Sultanate of Patani | |||||||||||

| Capital | Pattani | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Malay language (Classical Malay; court language Kelantan-Pattani Malay; spoken daily language) | ||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Established | 1457? | ||||||||||

• Conquest by Siam in 1786, later followed by annexation | 1902 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Thailand Malaysia | ||||||||||

The golden age of Patani started during the reign of the first of its four successive queens, Raja Hijau (The Green Queen), who came to the throne in 1584 and was followed by Raja Biru (The Blue Queen), Raja Ungu (The Purple Queen) and Raja Kuning (The Yellow Queen). During this period the kingdom's economic and military strength was greatly increased to the point that it was able to fight off four major Siamese invasions. It had declined by the late 17th century and it was invaded by Siam in 1786, which eventually absorbed the state after its last raja was deposed in 1902.

Predecessors

An early kingdom in the Patani area was the Hindu-Buddhist Langkasuka, founded in the region as early as the 2nd century CE.[1] It appeared in many accounts by Chinese travellers, among them was the Buddhist pilgrim I Ching. The kingdom drew trade from Chinese, Indian, and local traders as a stopping place for ships bound for, or just arrived from, the Gulf of Thailand. Langkasuka reached its greatest economic success in the 6th and 7th centuries and afterward declined as a major trade center. Political circumstances suggest that by the 11th century, Langkasuka was no longer a major port visited by merchants. However, much of the decline may be due to the silting up of the waterway linking it to the sea.

The most substantial ruins believed to be ancient Langkasuka have been found in Yarang located approximately 15 kilometres from the sea and the current city of Pattani.[2] How or when Langkasuka became replaced by Patani is not known; Hikayat Patani indicates that the immediate predecessor of Patani was Kota Mahligai whose ruler founded Patani, perhaps some time between 1350 and 1450.[3] This Patani was located in Keresik (name in Malay) or Kru Se (in Thai), a few kilometers to the east of the current city.[2]

However, some think Patani was the same country known to the Chinese as Pan Pan.

The region had been subject to Thai control for some time. In the 14th century CE, King Ram Khamhaeng the Great (c.1239 – 1317) of Sukhothai occupied Nakhon Si Thammarat and its vassal states which would include Patani if it had existed at that date. The Thai Ayutthaya kingdom also conquered the isthmus during the 14th century CE, and controlled many smaller vassal states in a self-governing system in which the vassal states and tributary provinces pledged allegiance to the king of Ayutthaya, but otherwise ran their own affairs.

Founding legends

Folklore suggests the name Patani means "this beach" which is "pata ni" in the local Malay language. In this story, a ruler went hunting one day and saw a beautiful white mouse-deer the size of a goat, which then disappeared. He asked his men where the animal had gone, and they replied: "Pata ni lah!" This ruler then ordered a town be built where the mouse-deer had disappeared it was then named after "this beach". The founder is named in some sources as either Sri Wangsa or Phaya Tunakpa, a ruler of Kota Malikha or Kota Mahligai.[4][5] The first ruler of Patani (some sources say his son) later converted to Islam and took the name Sultan Ismail Shah or Mahmud Shah.[6]

An alternative theory is that the Patani kingdom was founded in the 14th century. Local stories tell of a fisherman named Pak Tani (Father Tani), who was sent by a king from the interior to survey the coast, to find a place for an appropriate settlement. After he established a successful fishing outpost, other people moved to join him. The town soon grew into a prosperous trading center that continued to bear his name. The authors of the 17th–18th century Hikayat Patani chronicle claim this story is untrue, and support the claim that the kingdom was founded by the Sultan.

Early history

Patani has been suggested to be founded some time between 1350 and 1450, although its history before 1500 is unclear.[3] According to the Sejarah Melayu, Chau Sri Wangsa, a Siamese prince, founded Patani by conquering Kota Mahligai. He converted to Islam and took on the title of Sri Sultan Ahmad Shah in the late 15th to early 16th century.[7] The Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa and Hikayat Patani confirms the concept of kinship between Ayutthaya, Kedah, and Pattani, stating that they were descended from the same first dynasty. Patani may have become Islamised some time in the middle of 15th century, one source gives a date of 1470, but earlier dates have been proposed.[3] A story tells of a sheikh named Sa'id or Shafi'uddin from Kampong Pasai (presumably a small community of traders from Pasai who lived on the outskirts of Patani) reportedly healed the king of a rare skin disease. After much negotiation (and recurrence of the disease), the king agreed to convert to Islam, adopting the name Sultan Ismail Shah. All of the sultan's officials also agreed to convert. However, there is fragmentary evidence that some local people had begun to convert to Islam prior to this. The existence of a diasporic Pasai community near Patani shows the locals had regular contact with Muslims. There are also travel reports, such as that of Ibn Battuta, and early Portuguese accounts that claimed Patani had an established Muslim community even before Melaka (which converted in the 15th century), which would suggest that merchants who had contact with other emerging Muslims centres were the first to convert to the region.

Patani became more important after Malacca was captured by the Portuguese in 1511 as Muslim traders sought alternative trading ports. A Dutch source indicates that most of the traders were Chinese, but 300 Portuguese traders had also settled in Patani by 1540s.[3]

Sultan Ismail Shah was succeeded by Mudhaffar Shah.

The 16th century witnessed the rise of Burma, which under an aggressive dynasty made war on Ayutthaya. A second siege (1563–64) led by King Bayinnaung forced King Maha Chakkraphat to surrender in 1564.[8][9] The sultan of Patani Mudhaffar Shah helped the Burmese attack Ayutthaya in 1563, but died suddenly in 1564 on his way back to Patani. His brother Sultan Manzur Shah (1564–1572) who was left in charge in Patani while he was away then became the ruler of Patani.

Manzur Shah ruled for nine years, and after his death, Patani entered a period of political instability and violence. Two of its rulers were murdered by their relatives in fights for succession. The nine-year-old Raja Patik Siam (son of Mudhaffar Shah) and the regent (his aunt Raja Aisyah), were both murdered by his brother Raja Mambang, who was in turn killed. The son of Manzur Shah, Raja Bahdur, succeeded at the age of 10, but was later murdered by his half-brother Raja Bima after a dispute, and Raja Bima was himself killed.[5]

Four queens of Patani

Raja Hijau and the golden age of Patani

.JPG.webp)

Raja Hijau (or Ratu Hijau, the Green Queen) came to the throne in 1584, apparently the result of a lack of male heirs after they were all killed in the turbulent preceding period, and became the first queen of Patani. Raja Hijau acknowledged Siamese authority, and adopted the title of peracau derived from the Siamese royal title phra chao. Early in her reign she saw off an attempted coup by her prime minister, Bendahara Kayu Kelat. She also ordered that a channel be dug with a river dammed to divert water to ensure the supply of water to Patani.

Raja Hijau ruled for 32 years, and brought considerable stability to the country. During her reign, trade with the outside increased, and as a result Pattani prospered. It also become a centre of culture, producing high quality works of music, dance, drama and handicraft. An Englishman Peter Floris who visited Patani in 1612–1613 described a dance performed in Patani as the finest he had seen in the Indies.[10]

Growth as a trade entrepot

Chinese merchants were important in the rise of Patani as a regional trade center. Chinese, Malay and Siamese merchants traded throughout the area, as well as Persians, Indians and Arabs. They were joined by others including the Portuguese in 1516, Japanese in 1592, Dutch in 1602, English in 1612. Many Chinese also moved to Patani, perhaps due to the activity of Lin Daoqian.[11] A Dutch report of 1603 by Jacob van Neck estimated that there may be as many Chinese in Patani as there were native Malays, and they were responsible for most of the commercial activity of Patani.[12] The Dutch East India Company (VOC) established warehouses in Patani in 1603, followed by the English East India Company in 1612, both carrying out intense trading. In 1619, John Jourdain, the East India Company's chief factor at Bantam was killed off the coast of Patani by the Dutch. Ships were also lost, which eventually which led to the withdrawal of the English from Patani.[13][5]

Patani was seen by European traders as a way to access the Chinese market. After 1620, the Dutch and English both closed their warehouses, but a prosperous trade was continued by the Chinese, Japanese, and Portuguese for most of the 17th century.

The Blue and Purple Queens

Raja Hijau died on 28 August 1616 to be succeeded by her sister Raja Biru (the Blue Queen), who was around 50 when she became queen. Raja Biru persuaded the Kelantan Sultanate that lay to the south to become incorporated into Patani.[10]

After Raja Biru died in 1624, she was succeeded by her younger sister Raja Ungu (the Purple Queen). Raja Ungu, however, was more confrontational towards the Siamese, and abandoned the title Siamese title peracau, using instead the title paduka syah alam ("her excellency ruler of the world"). She stopped paying the Bunga mas tribute to Siam, and formed an alliance with Johor, marrying her daughter (who later became Raja Kuning) off to their ruler Sultan Abdul Jalil Shah III. However, her daughter was already married to the king of Bordelong (Phatthalung), Okphaya Déca, who prompted the Siamese to attack Patani in 1633–1634. Siam, however, failed to take Patani.[10]

The Yellow Queen and decline

Raja Ungu died in 1634, to be succeeded by the last of four successive female rulers of Patani Raja Kuning (or Ratu Kuning, the Yellow Queen). The war with Siam had caused considerable suffering to Patani as well as a significant decline in trade, and Raja Kuning adopted a more conciliatory stance towards the Siamese. The Siamese had intended to attack Patani again in 1635, but the Raja of Kedah intervened to help with the negotiation. In 1641, Raja Kuning visited the Ayutthaya court to resume good relation.[14] The power of the queen had declined by this period, and she did not appear to wield any significant political power.[10] In 1646, Patani joined other tributary states to rebel against Ayutthaya, but was later subdued by Ayutthaya.[14]

According to Kelantanese sources, Raja Kuning was deposed in 1651 by the Raja of Kelantan, who installed his son as the ruler of Patani, and the period of Kelantanese dynasty in Patani began. A different queen appeared to have been in control of Patani again by 1670, and three queens of Kelantan lineage may have ruled Patani from 1670 to 1718.[15][10]

When Phetracha took control of Ayutthaya in 1688, Patani refused to acknowledge his authority and rebelled. Ayutthaya then invaded with 50,000 men and subdued Patani.[15] Following the invasion, political disorder continued for five decades, during which the local rulers were helpless to end the lawlessness of the region, and most foreign merchants abandoned trade with Patani. Towards the end of the 17th century, Patani was described in Chinese sources as sparsely populated and barbaric.[10]

Reassertion of Thai power

.jpg.webp)

In the 18th century, Ayutthaya under King Ekkathat (Boromaraja V) faced another Burmese invasion. This culminated in the capture and destruction of the city of Ayutthaya in 1767, as well as the death of the king. Siam was shattered, and as rivals fought for the vacant throne, Patani declared its complete independence.

King Taksin finally defeated the Burmese and reunified the country, opening the way for the establishment of the Chakri dynasty by his successor, King Rama I. In 1786, a resurgent Siam sent an army led by Prince Surasi (Viceroy Boworn Maha Surasinghanat), younger brother of King Rama I, to seek the submission of Patani.

Patani in the Bangkok Period

Patani was easily defeated by Siam in 1786 and resumed its tributary status. The city of Patani itself was sacked and destroyed, and a new town was later created a few miles to the west. However, a series of attempted rebellions prompted Bangkok to divide Patani into seven smaller puppet states in the early 1800s during the reign of King Rama II. Britain recognised the Thai ownership of Patani by the Burney Treaty in 1826. The throne stayed vacant for a few decades until 1842, when a member of the Kelantanese royalty returned to reclaim the throne. While the raja ruled over Patani independently of Siam, Patani also recognised the authority of Siam and regularly sent the bunga mas tribute. In 1902, in a bid to assert full control of Patani, Siam arrested and deposed the last raja of Patani after he refused Siam's demand for administrative reform, thus ending Patani as an independent state.[16]

Chronology of rulers

Inland dynasty (Sri Wangsa)

- Chau Sri Wangsa (c. 1488-1511), the Siamese prince said in some sources to have conquered Kota Mahligai and founded the settlement of Patani, converted to Islam, took on the title of Sri Sultan Ahmad Shah.[17][7]

- Raja Intera/Phaya Tu Nakpa/Sultan Ismail Shah/Mahmud Shah (d. 1530?), founder of the kingdom according to one account, and the first ruler to convert to Islam. In fact, other rulers must have preceded him. It is also likely that during his reign the Portuguese first visited the port to trade, arriving in 1516.

- Sultan Mudhaffar Shah (c. 1530–1564), son of Sultan Ismail Shah, who died during an attack on Ayudhya (Siam).

- Sultan Manzur Shah (1564–1572), brother of Sultan Mudhaffar Shah.

- Sultan Patik Siam (1572–1573), son of Sultan Mudhaffar Shah, who was murdered by his half-brother, Raja Bambang.

- Sultan Bahdur (1573–1584), son of Sultan Manzur Shah, who was considered a tyrant in most accounts.

- Ratu Hijau (the Green Queen) (1584–1616), sister of Sultan Bahdur, during whose reign Patani attained its greatest economic success as a middle-sized port, frequented by Chinese, Dutch, English, Japanese, Malays, Portuguese, Siamese, and other merchants.

- Ratu Biru (the Blue Queen) (1616–1624), sister of Ratu Hijau.

- Ratu Ungu (the Purple Queen) (1624–1635), sister of Ratu Biru, who was particularly opposed to Siamese interference in local affairs.

- Ratu Kuning (the Yellow Queen) (1635-1649/88), daughter of Ratu Ungu and last queen of the Inland dynasty. Controversy surrounds the exact date of the end of her reign.

| History of Malaysia |

|---|

|

|

|

First Kelantanese dynasty

- Raja Bakal, (1688–1690 or 1651–1670), after a brief invasion of Patani by his father in 1649, Raja Sakti I of Kelantan, he was given the throne in Patani.

- Raja Emas Kelantan (1690–1704 or 1670–1698), thought by Teeuw & Wyatt to be a king, but claimed by al-Fatani to be a queen, the widow of Raja Bakal and mother of the succeeding queen.

- Raja Emas Chayam (1704–1707 or 1698–1702 and 1716–1718), daughter of the two preceding rulers, according to al-Fatani.

- Raja Dewi (1707–1716; Fatani gives no dates).

- Raja Bendang Badan (1716–1720 or ?-1715), he was afterwards raja of Kelantan, 1715–1733.

- Raja Laksamana Dajang (1720–1721; Fatani gives no dates).

- Raja Alung Yunus (1728–1729 or 1718–1729).

- Raja Yunus (1729–1749).

- Raja Long Nuh (1749–1771).

- Sultan Muhammad (1771–1785).

- Tengku Lamidin (1785–1791).

- Datuk Pengkalan (1791–1808).

Second Kelantanese dynasty

- Sultan Phraya Long Muhammad Ibni Raja Muda Kelantan/Raja Kampong Laut Tuan Besar Long Ismail Ibni Raja Long Yunus (1842–1856)

- Tuan Long Puteh Bin Sultan Phraya Long Muhammad (Phraya Pattani II) (1856–1881)

- Tuan Besar Bin Tuan Long Puteh (Phraya Pattani III) (1881–1890)

- Tuan Long Bongsu Bin Sultan Phraya Long Muhammad (Sultan Sulaiman Sharafuddin Syah / Phraya Pattani IV)(1890–1898)

- Sultan Abdul Kadir Kamaruddin Syah (Phraya Pattani V) deposed in 1902 had descendants:

- Tengku Sri Akar Ahmad Zainal Abidin

- Tengku Mahmood Mahyidden

- Tengku Besar Zubaidah, married Tengku Ismail the son of Tuan Long Besar (Phraya Pattani III), had descendants:

- Tengku Budriah of Perlis, Raja Perempuan of Perlis and Raja Permaisuri Agong (1924–2008)

- Tengku Ahmad Rithaudeen, former Minister of Trade and Industry, Defence, Information, Foreign Affairs and Member of the Dewan Rakyat in Kota Bharu (1929–2022)

- Tengku Noor Zakiah, Malaysian Stockbroker, chairman of KIBB (Kenanga International Bank Berhad) (1926–)

- Tengku Kamaruzzaman

See also

References

- Teeuw, A.; Wyatt, D. K. (14 March 2013). Hikayat Patani the Story of Patani. Springer. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9789401525985.

- Le Roux, Pierre (1998). "Bedé kaba' ou les derniers canons de Patani". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. 85: 125–162. doi:10.3406/befeo.1998.2546.

- Bougas, Wayne (1990). "Patani in the Beginning of the XVII Century". Archipel. 39: 113–138. doi:10.3406/arch.1990.2624.

- Wyatt, David K. (December 1967). "A Thai Version of Newbold's "Hikayat Patani"". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 40 (2 (212)): 16–37. JSTOR 41491922.

- Ibrahim Syukri. "Chapter 2 :The Development of Patani and the Descent of its Rajas". History of Patani., from History of the Malay Kingdom of Patani. ISBN 0-89680-123-3

- History of the Malay Kingdom of Patani, Ibrahim Syukri, ISBN 0-89680-123-3

- Robson, Stuart (1996). "Panji and Inao: Questions of Cultural and Textual History" (PDF). The Siam Society. The Siam Society under Royal Patronage. p. 45. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

One could also mention the tradition recorded in the Sejarah Melayu, namely of a conquest of Kota Mahligai by a Siamese prince called Chau Sri Bangsa, his conversion to Islam, the foundation of a new settlement on the coast which was named Pattani, and the sending of a "drum of sovereignty" by Sultan Mahmud Shah of Malacca. Having been installed to the beat of the drum, Chau Sri Bangsa took the title of Sri Sultan Ahmad Shah (Brown 1952, 152). This reference to Sultan Mahmud Shah of Malacca would place us in the period 1488-1511.

- Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur P. Phayre (1883). History of Burma (1967 ed.). London: Susil Gupta. p. 111.

- GE Harvey (1925). History of Burma. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd. pp. 167–170.

- Amirell, Stefan (2011). "The Blessings and Perils of Female Rule: New Perspectives on the Reigning Queens of Patani, c. 1584–1718". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 42 (2): 303–23. doi:10.1017/S0022463411000063. S2CID 143695148.

- Yen Ching-hwang (13 September 2013). Ethnic Chinese Business In Asia: History, Culture And Business Enterprise. World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 57. ISBN 9789814578448.

- Anthony Reid (30 August 2013). Patrick Jory (ed.). Ghosts of the Past in Southern Thailand: Essays on the History and Historiography of Patani. NUS Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-9971696351.

- Keay, John (2010). The Honourable Company: A History of the English East India Company (EPUB ed.). Harper Collins Publishers. p. location 1218. ISBN 978-0-007-39554-5.

- "1600 - 1649". History of Ayutthaya.

- Barbara Watson Andaya; Leonard Y Andaya (11 November 2016). A History of Malaysia. Red Globe Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1137605153.

- Koch, Margaret L. (1977). "Patani and the Development of A Thai State". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 50 (2 (232)): 69–88. JSTOR 41492172.

- Rentse, Anker (1934). "History of Kelantan. I". Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 12 (2 (119)): 47. JSTOR 41559510. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

Further reading

- Ibrahim Syukri. History of the Malay Kingdom of Patani. ISBN 0-89680-123-3.

- Thailand: Country Studies by the Library of Congress, Federal Research Division http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/thtoc.html

- Maryam Salim. (2005). The Kedah Laws. Dewan Bahasa and Pustaka. ISBN 983-62-8210-6

- "พงศาวดารเมืองปัตตานี" ประชุมพงศาวดาร ภาคที่ 3, พระนคร : หอพระสมุดวชิรญาณ, 2471 (พิมพ์ในงานศพ หลวงชินาธิกรณ์อนุมัติ 31 มีนาคม 2470) – Historical account of Patani made by a Thai official.

External links

Media related to Sultanate of Patani at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sultanate of Patani at Wikimedia Commons- From Bunga Mas to Minarets