Damocles

Damocles[lower-alpha 1] is a character who appears in a (likely apocryphal) anecdote commonly referred to as "the sword of Damocles",[1][2] an allusion to the imminent and ever-present peril faced by those in positions of power. Damocles was a courtier in the court of Dionysius I of Syracuse,[3] a ruler of Syracuse, Sicily, Magna Graecia, during the classical Greek era.

| Damocles Δαμοκλῆς | |

|---|---|

In Richard Westall's Sword of Damocles, 1812, the boys of Cicero's anecdote have been changed to maidens for a neoclassical patron, Thomas Hope. | |

| In-universe information | |

| Occupation | Courtier |

The anecdote apparently figured in the lost history of Sicily by Timaeus of Tauromenium (c. 356 – c. 260 BC). The Roman orator Cicero (c. 106 – c. 43 BC)[4] may have read it in the texts of Greek historian Diodorus Siculus and used it in his Tusculanae Disputationes, 5. 61,[1] by which means it passed into the European cultural mainstream.

Sword of Damocles

According to the story, Damocles was flattering his king, Dionysius, exclaiming that Dionysius was truly fortunate as a great man of power and authority without peer, surrounded by magnificence. In response, Dionysius offered to switch places with Damocles for one day so that Damocles could taste that very fortune first-hand. Damocles quickly and eagerly accepted the king's proposal. Damocles sat on the king's throne amid countless luxuries. There were beautifully embroidered rugs, fragrant perfumes, and the most select of foods, piles of silver and gold, and the service of attendants unparalleled in their beauty, surrounding Damocles with riches and excess. But Dionysius, who had made many enemies during his reign, arranged that a sword should hang above the throne, held at the pommel only by a single hair of a horse's tail to evoke the sense of what it is like to be king: though having much fortune, always having to watch in fear and anxiety against dangers that might try to overtake him. Damocles finally begged the king to be allowed to depart because he no longer wanted to be so fortunate, realizing that while he had everything he could ever want at his feet, it could not affect what was above his crown.

King Dionysius effectively conveyed the constant fear in which a person with great power may live. Dionysius committed many cruelties in his rise to power, such that he could never go on to rule justly because that would make him vulnerable to his enemies. Cicero used this story as the last in a series of contrasting examples for concluding his fifth Disputation, in which the theme is that having virtue is sufficient for living a happy life.[5][6]

.JPG.webp)

Differing interpretations

Cicero's meaning in the story of the Sword of Damocles has alternative interpretations. Cicero states, "Doesn't Dionysius seem to have made it plenty clear that nothing is happy for him over whom terror always looms?" arguing that those in positions of power can never rest and truly enjoy that power.[8] Some take this and argue further, stating that the point was that death looms over all, but that it is vital to strive to be happy and enjoy life in spite of that terror.[9] Others take the meaning to be something akin to "don't judge someone until you've walked a mile in their shoes," as it is impossible to know what someone is struggling with, even if their life seems to be perfect to the outside observer. Just as King Dionysius' life looked luxurious and flawless on the outside to Damocles, so too might the lives of others that one covets for oneself.[9] One other interpretation sees the story of the sword of Damocles as explicitly meant for Julius Caesar, implicitly suggesting that he should take care not to act the same way that King Dionysius did, making enemies and denying spiritual life, falling prey to the pitfalls of the tyrant, and mind the sword hanging ever-present over his neck.[10]

Use in culture, art, and literature

The sword of Damocles is frequently used in allusion to this tale, epitomizing the imminent and ever-present peril faced by those in positions of power. More generally, it is used to denote the sense of foreboding engendered by a precarious situation,[11] especially one in which the onset of tragedy is restrained only by a delicate trigger or chance. Shakespeare's Henry IV expands on this theme: "Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown";[12] compare the Hellenistic and Roman imagery connected with the insecurity offered by Tyche and Fortuna.

In The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer refers to the sword of Damocles, which the Knight describes as hanging over Conquest. When the Knight describes the three temples, he also pays special attention to the paintings, noticing one on the walls of the temple of Mars:

Above, where seated in his tower,

I saw Conquest depicted in his power

There was a sharpened sword above his head

That hung there by the thinnest simple thread.

- — (lines 2026–2030.)[13]

The Roman 1st-century BC poet Horace also alluded to the sword of Damocles in Ode 1 of the Third Book of Odes, in which he extolled the virtues of living a simple, rustic life, favoring such an existence over the myriad threats and anxieties that accompany holding a position of power. In this appeal to his friend and patron, the aristocratic Gaius Maecenas, Horace describes the Siculae dapes or "Sicilian feasts" as providing no savory pleasure to the man, "above whose impious head hangs a drawn sword (destrictus ensis)."[14]

The phrase has also come to be used in describing any situation infused with a sense of impending doom, especially when the peril is visible and proximal—regardless of whether the victim is in a position of power. US President John F. Kennedy compared the omnipresent threat of nuclear annihilation to a sword of Damocles hanging over the people of the world.[15] Soviet First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev wanted the Tsar Bomba to "hang like the sword of Damocles over the imperialists' heads".[16]

Woodcut images of the sword of Damocles as an emblem appear in 16th- and 17th-century European books of devices, with moralizing couplets or quatrains, with the import METUS EST PLENUS TYRANNIS.[17] A small vignette shows Damocles under a canopy of state, at the festive table, with Dionysius seated nearby;[18] the etching, with its clear political moral, was later used to illustrate the idea.[19][20]

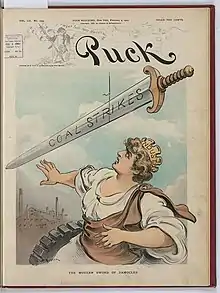

References to the sword of Damocles can also be found in cartoonist illustrations, such as in Joseph Keppler's magazine Puck,[21] a satiric periodical started in the late 1800s in the United States, and the sword can be used as a device to call attention to the peril that current events or contentious issues of the time place the world in.

The sword of Damocles frequently appears in popular culture, including novels, feature films, television series, video games, and music.[22] Some notable examples include Damocles, a 16-bit videogame from 1990 in which the player races to prevent the titular comet Damocles from destroying a planet,[23] the song "The Sword of Damocles" from The Rocky Horror Picture Show,[24] and a virtual reality headset also called The Sword of Damocles, developed by Ivan Sutherland in 1968, named for its suspension from the ceiling of the lab in which it was developed and its foreboding appearance.[22]

In Made in Canada, a Canadian show that ran from 1998 to 2003, Sword of Damacles was the name of an in-series TV show produced by Pyramid, the production company the show centres around.

The Damocles is the name of the ship that is used in a multi-episode plot-line that spanned multiple seasons of the TV show NCIS.

The sword of Damocles is an oft-used symbol in modern hip hop, an allusion used to impart the threat "kingly" rappers face of being deposed as the best of the best. It is referenced in the lyrics of the song "Zealots" by The Fugees in 1996.[8] It also appears in the music of Kanye West, both in the music video for his single "Power" in 2010, where a sword is positioned above West's head as he stands amidst rows of Ionic columns, and in later cover art for the song, which features the impaled head of a black man wearing a crown.[8]

References

- Cicero.

- Westall.

- "Cicero's Tusculan Disputations, On the Nature of the Gods, On the Commonwealth". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2023-06-01.

- "Marcus Tullius Cicero". 2012-08-07. Archived from the original on 2012-08-07. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- Cicero, 5.1: ‘virtutem ad beate vivendum se ipse esse contentam’

- Jaeger, Mary (14 March 2012). "Cicero and Archimedes' tomb". Journal of Roman Studies. 92: 49–61, esp. 51ff. doi:10.2307/3184859. JSTOR 3184859. S2CID 162402665.

- "HERBERT GANDY (BRITISH 1857-1934)". shapiroauctions.com. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- Peralta, Dan-el Padilla (2017-11-14). "From Damocles to Socrates". Medium. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- Jaeger, Mary (November 2002). "Cicero and Archimedes' Tomb". Journal of Roman Studies. 92: 49–61. doi:10.2307/3184859. ISSN 0075-4358. JSTOR 3184859. S2CID 162402665.

- Verbaal, Wim (2006). "Cicero and Dionysios the Elder, or the End of Liberty". Classical World. 99 (2): 145–156. doi:10.1353/clw.2006.0050. ISSN 1558-9234. S2CID 161906192.

- "Damocles". Benet's Reader's Encyclopedia. 1948.

Evil foreboded or dreaded

- Shakespeare, William (1597). "Part II". Henry IV.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Chaucer, Geoffrey (1475). "The Knight's Tale". The Canterbury Tales (online quotation in context). UK: Florida State University – via english.fsu.edu.

- "Carmina (Horatius)". Latin Wikisource. liber III, carmen I – via Wikisource.

- Kennedy, John Fitzgerald (25 September 1961). "Address before the General Assembly of the United Nations". Selected Speeches. Columbia Point, Boston, Massachusetts: Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

Today, every inhabitant of this planet must contemplate the day when this planet may no longer be habitable. Every man, woman, and child lives under a nuclear sword of Damocles, hanging by the slenderest of threads, capable of being cut at any moment by accident or miscalculation or by madness.

- Isaacs, Jeremy; Mitchell, Pat, eds. (1998). The Cold War (DVD). CNN.

- Some examples: La Perrière, Guillaume (1553). Morosophie. Glasgow, Scotland, UK: Glasgow University. emblem 30.; Paradin, Claude (1557). Coelitus impendet [It hangs from Heaven]. Devises heroïques (in Latin). Glasgow, Scotland, UK: Glasgow University.; Boissard, Jean Jacques (1593). Emblematum Liber. Glasgow, Scotland, UK: Glasgow University. emblem 45.

- Hollar, Wenceslaus (n.d.). Emblemata Nova. London, UK.

- Hobbes, Thomas (1651). Philosophicall Rudiments Concerning Government and Society. London.

- Pennington, Richard (1982). A Descriptive Catalogue of the Etched Work of Wenceslaus Hollar, 1607–1677. Cambridge University Press.

- "U.S. Senate: Puck Magazine". www.senate.gov. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- For example:

Literature: Wodehouse, P.G. (1963). Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves.; Bohumil Hrabal (1990). Příliš hlučná samota [Too Loud a Solitude]. Hermans, W.F. (1958). De Donkere Kamer van Damocles [The Darkroom of Damocles].

Film: Half-Wits Holiday (1947), The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), Escape from L.A. (1996).

TV series: "The 100" season 5, episode 12,13. 2014.; "Burns Verkaufen der Kraftwerk". The Simpsons. Episode 11. 1991.; "Work Experience". The Office. Episode 2. 2001.; "Jumping the Shark". Reno 911!. Episode 1. 2008.; Code Geass (TV broadcast). Vol. 2. 2008.; K (anime) (TV broadcast). 2012.

Videogames: Damocles (1990), Tomb Raider (1996); MechWarrior 3 (1999); Max Payne 2: The Fall of Max Payne (2003); E.Y.E.: Divine Cybermancy (2011); Ryse: Son of Rome (2013); The Binding of Isaac: Repentance (2021).

Music: Toto (1978). Toto (album) (audio recording). Toto (1979). Hydra (audio recording). Toto (1984). Toto IV (audio recording). (see "SWORD, THE". May 2007.); Reed, Lou (1992). Sword of Damocles Externally (audio recording).; The Fugees and Wyclef Jean (1996). Zealots (audio recording).; Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds (2001). Oh My Lord (audio recording).; Iron Maiden (2013). Starblind (audio recording). - Guyart, S.; Hurt, A.; Garycki, P.; Berry, S.; Sachs, M. (2004). "Hints and solution for Damocles". The Mercenary Site. Archived from the original on 2005-04-09. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- Ruhlmann, William, The Rocky Horror Picture Show [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack] - Various Artists | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic, retrieved 2021-05-21

Works cited

- Cicero, Tusculan Disputations (translation), Livius.org, V. 61.

- Westall, Richard, The sword of Damocles (painting), Ackland Art Museum, UNC, archived from the original on 13 August 2018.

External links

The dictionary definition of damocles at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of damocles at Wiktionary Media related to Sword of Damocles at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sword of Damocles at Wikimedia Commons