Taj Mahal

The Taj Mahal (/ˌtɑːdʒ məˈhɑːl, ˌtɑːʒ-/; lit. 'Crown of the Palace')[4][5][6] is an ivory-white marble mausoleum on the right bank of the river Yamuna in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India. It was commissioned in 1631 by the fifth Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658) to house the tomb of his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal; it also houses the tomb of Shah Jahan himself. The tomb is the centrepiece of a 17-hectare (42-acre) complex, which includes a mosque and a guest house, and is set in formal gardens bounded on three sides by a crenellated wall.

| Taj Mahal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| Coordinates | 27°10′30″N 78°02′31″E |

| Area | 17 hectares (42 acres)[1] |

| Height | 73 m (240 ft) |

| Built | 1631–1653[2] |

| Built for | Mumtaz Mahal |

| Architect | Ustad Ahmad Lahori |

| Architectural style(s) | Mughal architecture |

| Visitors | 6,532,366[3] (in 2019) |

| Governing body | Government of India |

| Website | www.tajmahal.gov.in |

Location of Taj Mahal in Uttar Pradesh, India  Taj Mahal (India) | |

| Criteria | Cultural: i |

| Reference | 252 |

| Inscription | 1983 (7th Session) |

Construction of the mausoleum was essentially completed in 1643, but work continued on other phases of the project for another 10 years. The Taj Mahal complex is believed to have been completed in its entirety in 1653 at a cost estimated at the time to be around ₹32 million, which in 2023 would be approximately ₹35 billion.[7] The construction project employed some 20,000 artisans under the guidance of a board of architects led by Ustad Ahmad Lahori, the emperor's court architect. Various types of symbolism have been employed in the Taj to reflect natural beauty and divinity.

The Taj Mahal was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983 for being "the jewel of Muslim art in India and one of the universally admired masterpieces of the world's heritage". It is regarded by many as the best example of Mughal architecture and a symbol of India's rich history. The Taj Mahal attracts 7-8 million visitors a year,[8] and in 2007 it was declared a winner of the New 7 Wonders of the World (2000–2007) initiative.

Etymology

Abdul Hamid Lahori, in his book from 1636 Padshahnama, refers to the Taj Mahal as rauza-i munawwara (Perso-Arabic: روضه منواره, rawdah-i munawwarah), meaning the illumined or illustrious tomb.[9] The current name for the Taj Mahal is of Urdu origin, and believed to be derived from Arabic and Persian, with the words tāj mahall meaning "crown" (tāj) "palace" (mahall).[10][11][4] The name "Taj" came from the corruption of the second syllable of "Mumtaz".[12][13]

Inspiration

The Taj Mahal was commissioned by Shah Jahan in 1631, to be built in the memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died on 17 June that year, while giving birth to their 14th child, Gauhara Begum.[14][15] Construction started in 1632,[16] and the mausoleum was completed in 1648, while the surrounding buildings and garden were finished five years later.[17] The imperial court documenting Shah Jahan's grief after the death of Mumtaz Mahal illustrates the love story held as the inspiration for the Taj Mahal.[18] According to contemporary historians Muhammad Amin Qazvini, Abdul Hamid Lahori and Muhammad Saleh Kamboh, he did not show the same level of affection to others as he had shown her while she was alive. He avoided royal affairs for a week due to his grief, along with giving up listening to music and dressing lavishly for two years. Shah Jahan was enamored by the beauty of the land at the south side of Agra on which a mansion belonging to Raja Jai Singh I stood. This place was chosen for the construction of Mumtaz's tomb by Shah Jahan and Jai Singh agreed to donate it to the emperor.[19]

"Shah Jahan on a globe" from the Smithsonian Institution

"Shah Jahan on a globe" from the Smithsonian Institution Artistic depiction of Mumtaz Mahal

Artistic depiction of Mumtaz Mahal

Architecture and design

The Taj Mahal incorporates and expands on design traditions of Indo-Islamic and earlier Mughal architecture. Specific inspiration came from successful Timurid and Mughal buildings including the Gur-e Amir (the tomb of Timur, progenitor of the Mughal dynasty, in Samarkand),[20] Humayun's Tomb which inspired the Charbagh gardens and hasht-behesht (architecture) plan of the site, Itmad-Ud-Daulah's Tomb (sometimes called the Baby Taj), and Shah Jahan's own Jama Masjid in Delhi. While earlier Mughal buildings were primarily constructed of red sandstone, Shah Jahan promoted the use of white marble inlaid with semi-precious stones. Buildings under his patronage reached new levels of refinement.[21]

Tomb

The tomb is the central focus of the entire complex of the Taj Mahal. It is a large, white marble structure standing on a square plinth and consists of a symmetrical building with an iwan (an arch-shaped doorway) topped by a large dome and finial. Like most Mughal tombs, the basic elements are Indo-Islamic in origin.[22]

The base structure is a large multi-chambered cube with chamfered corners forming an unequal eight-sided structure that is approximately 55 metres (180 ft) on each of the four long sides. Each side of the iwan is framed with a huge pishtaq or vaulted archway with two similarly shaped arched balconies stacked on either side. This motif of stacked pishtaqs is replicated on the chamfered corner areas, making the design completely symmetrical on all sides of the building. Four minarets frame the tomb, one at each corner of the plinth facing the chamfered corners. The main chamber houses the false sarcophagi of Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan; the actual graves are at a lower level.[23]

_to_the_Taj_Mahal.jpg.webp) The main gateway (darwaza) to the Taj Mahal

The main gateway (darwaza) to the Taj Mahal Taj Mahal minaret

Taj Mahal minaret Taj Mahal at sunrise from Main Entrance

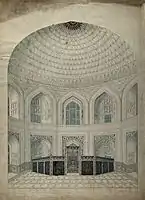

Taj Mahal at sunrise from Main Entrance Sketch of the interior view of the vaulted dome over the tombs of Shah Jahan (left) and Mumtaz Mahal (right)

Sketch of the interior view of the vaulted dome over the tombs of Shah Jahan (left) and Mumtaz Mahal (right) The false sarcophagi of Mumtaz Mahal (right) and Shah Jahan (left) in the main chamber

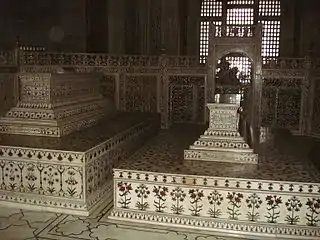

The false sarcophagi of Mumtaz Mahal (right) and Shah Jahan (left) in the main chamber The actual tombs of Mumtaz Mahal (right) and Shah Jahan (left) in the lower level. Mumtaz's grave does not have a lower slab like that of Shah Jahan.

The actual tombs of Mumtaz Mahal (right) and Shah Jahan (left) in the lower level. Mumtaz's grave does not have a lower slab like that of Shah Jahan. Main marble dome, smaller domes, and decorative spires that extend from the edges of the base walls

Main marble dome, smaller domes, and decorative spires that extend from the edges of the base walls.jpg.webp) Arabic calligraphy at the tomb entrance

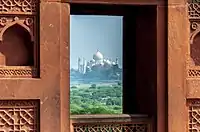

Arabic calligraphy at the tomb entrance A window view of Taj Mahal from Agra Fort

A window view of Taj Mahal from Agra Fort Taj Mahal

Taj Mahal

The most spectacular feature is the marble dome that surmounts the tomb. The dome is nearly 35 metres (115 ft) high which is close in measurement to the length of the base, and accentuated by the cylindrical "drum" it sits on, which is approximately 7 metres (23 ft) high. Because of its shape, the dome is often called an onion dome or amrud (guava dome).[24] The top is decorated with a lotus design which also serves to accentuate its height. The shape of the dome is emphasised by four smaller domed chattris (kiosks) placed at its corners, which replicate the onion shape of the main dome. The dome is slightly asymmetrical.[25] Their columned bases open through the roof of the tomb and provide light to the interior. Tall decorative spires (guldastas) extend from edges of base walls, and provide visual emphasis to the height of the dome. The lotus motif is repeated on both the chattris and guldastas. The dome and chattris are topped by a gilded finial which mixes traditional Persian and Hindustani decorative elements.[26]

The main finial was originally made of gold but was replaced by a copy made of gilded bronze in the early 19th century. This feature provides a clear example of integration of traditional Persian and Hindu decorative elements.[27] The finial is topped by a moon, a typical Islamic motif whose horns point heavenward.[28]

The minarets, which are each more than 40 metres (130 ft) tall, display the designer's penchant for symmetry. They were designed as working minarets – a traditional element of mosques, used by the muezzin to call the Islamic faithful to prayer. Each minaret is effectively divided into three equal parts by two working balconies that ring the tower. At the top of the tower is a final balcony surmounted by a chattri that mirrors the design of those on the tomb. The chattris all share the same decorative elements of a lotus design topped by a gilded finial. The minarets were constructed slightly outside of the plinth so that in the event of collapse, a typical occurrence with many tall constructions of the period, the material from the towers would tend to fall away from the tomb.[29]

Exterior decorations

The exterior decorations of the Taj Mahal are among the finest in Mughal architecture. As the surface area changes, the decorations are refined proportionally. The decorative elements were created by applying paint, stucco, stone inlays or carvings. In line with the Islamic prohibition against the use of anthropomorphic forms, the decorative elements can be grouped into either calligraphy, abstract forms or vegetative motifs. Throughout the complex are passages from the Qur'an that comprise some of the decorative elements. Recent scholarship suggests that Amanat Khan chose the passages.[30][31]

The calligraphy on the Great Gate reads "O Soul, thou art at rest. Return to the Lord at peace with Him, and He at peace with you."[31] The calligraphy was created in 1609 by a calligrapher named Abdul Haq. Shah Jahan conferred the title of "Amanat Khan" upon him as a reward for his "dazzling virtuosity".[32] Near the lines from the Qur'an at the base of the interior dome is the inscription, "Written by the insignificant being, Amanat Khan Shirazi".[33] Much of the calligraphy is composed of florid thuluth script made of jasper or black marble[32] inlaid in white marble panels. Higher panels are written in slightly larger script to reduce the skewing effect when viewed from below. The calligraphy found on the marble cenotaphs in the tomb is particularly detailed and delicate.

Abstract forms are used throughout, especially in the plinth, minarets, gateway, mosque, jawab and, to a lesser extent, on the surfaces of the tomb. The domes and vaults of the sandstone buildings are worked with tracery of incised painting to create elaborate geometric forms. Herringbone inlays define the space between many of the adjoining elements. White inlays are used in sandstone buildings, and dark or black inlays on the white marbles. Mortared areas of the marble buildings have been stained or painted in a contrasting colour which creates a complex array of geometric patterns. Floors and walkways use contrasting tiles or blocks in tessellation patterns.[34]

On the lower walls of the tomb are white marble dados sculpted with realistic bas relief depictions of flowers and vines. The marble has been polished to emphasise the exquisite detailing of the carvings. The dado frames and archway spandrels have been decorated with pietra dura inlays of highly stylised, almost geometric vines, flowers and fruits. The inlay stones are of yellow marble, jasper and jade, polished and levelled to the surface of the walls.[32]

Taj Mahal Exterior with a minaret

Taj Mahal Exterior with a minaret Detail of plant motifs on Taj Mahal wall

Detail of plant motifs on Taj Mahal wall Base, dome and minaret

Base, dome and minaret Finial, tamga of the Mughal Empire

Finial, tamga of the Mughal Empire Plant motifs

Plant motifs Reflective tiles

Reflective tiles Marble jali (latticed grill)

Marble jali (latticed grill).jpg.webp)

Interior decoration

The interior chamber of the Taj Mahal reaches far beyond traditional decorative elements. The inlay work is not pietra dura, but a lapidary of precious and semiprecious gemstones.[35] The inner chamber is an octagon with the design allowing for entry from each face, although only the door facing the garden to the south is used. The interior walls are about 25 metres (82 ft) high and are topped by a "false" interior dome decorated with a sun motif. Eight pishtaq arches define the space at ground level and, as with the exterior, each lower pishtaq is crowned by a second pishtaq about midway up the wall.[36] The four central upper arches form balconies or viewing areas, and each balcony's exterior window has an intricate screen or jali a grill lattice cut from marble. In addition to the light from the balcony screens, light enters through roof openings covered by chattris at the corners. The octagonal marble screen or jali bordering the cenotaphs is made from eight marble panels carved through with intricate pierce work. The remaining surfaces are inlaid in delicate detail with semi-precious stones forming twining vines, fruits and flowers. Each chamber wall is highly decorated with dado bas-relief, intricate lapidary inlay and refined calligraphy panels which reflect, in little detail, the design elements seen throughout the exterior of the complex.[37]

Flowers carved in marble

Flowers carved in marble Detail of pietra dura jali inlay

Detail of pietra dura jali inlay Delicacy of intricate pierce work

Delicacy of intricate pierce work Archways in the mosque

Archways in the mosque Incised painting

Incised painting Finial floor tiling

Finial floor tiling Detail of jali

Detail of jali.jpg.webp) Pietra dura, or parchin kari, flowers

Pietra dura, or parchin kari, flowers

Muslim tradition forbids elaborate decoration of graves. Hence, the bodies of Mumtaz and Shah Jahan were put in a relatively plain crypt beneath the inner chamber with their faces turned right, towards Mecca. Mumtaz Mahal's cenotaph is placed at the precise centre of the inner chamber on a rectangular marble base of 1.5 by 2.5 metres (4 ft 11 in by 8 ft 2 in). Both the base and casket are elaborately inlaid with precious and semiprecious gems. Calligraphic inscriptions on the casket identify and praise Mumtaz. On the lid of the casket is a raised rectangular lozenge meant to suggest a writing tablet. Shah Jahan's cenotaph is beside Mumtaz's to the western side and is the only visible asymmetric element in the entire complex. His cenotaph is bigger than his wife's, but reflects the same elements: a larger casket on a slightly taller base precisely decorated with lapidary and calligraphy that identifies him. On the lid of the casket is a traditional sculpture of a small pen box.[36]

The pen box and writing tablet are traditional Mughal funerary icons decorating the caskets of men and women respectively. The Ninety Nine Names of God are calligraphic inscriptions on the sides of the actual tomb of Mumtaz Mahal. Other inscriptions inside the crypt include: O Noble, O Magnificent, O Majestic, O Unique, O Eternal, O Glorious... . The Tomb of Shah Jahan bears a calligraphic inscription that reads: He travelled from this world to the banquet-hall of Eternity on the night of the twenty-sixth of the month of Rajab, in the year 1076 Hijri.[38]

Garden

The complex is set around a large 300-metre (980 ft) square charbagh or Mughal garden. The garden uses raised pathways that divide each of the four-quarters of the garden into 16 sunken parterres or flowerbeds. Halfway between the tomb and gateway in the centre of the garden is a raised marble water tank with a reflecting pool positioned on a north–south axis to reflect the image of the mausoleum. The elevated marble water tank is called al Hawd al-Kawthar in reference to the "Tank of Abundance" promised to Muhammad.[39]

Elsewhere, the garden is laid out with avenues of trees labelled according to common and scientific names[40] and fountains. The charbagh garden, a design inspired by Persian gardens, was introduced to India by Babur, the first Mughal emperor. It symbolises the four flowing rivers of Jannah (Paradise) and reflects the Paradise garden derived from the Persian paridaeza, meaning 'walled garden.' In mystic Islamic texts of the Mughal period, Paradise is described as an ideal garden of abundance with four rivers flowing from a central spring or mountain, separating the garden into north, west, south and east.

Most Mughal charbaghs are rectangular with a tomb or pavilion in the centre. The Taj Mahal garden is unusual in that the main element, the tomb, is located at the end of the garden. With the discovery of Mahtab Bagh or "Moonlight Garden" on the other side of the Yamuna, the interpretation of the Archaeological Survey of India is that the Yamuna river itself was incorporated into the garden's design and was meant to be seen as one of the rivers of Paradise.[41] Similarities in layout and architectural features with the Shalimar Gardens suggests both gardens may have been designed by the same architect, Ali Mardan.[42] Early accounts of the garden describe its profusion of vegetation, including abundant roses, daffodils, and fruit trees.[43] As the Mughal Empire declined, the Taj Mahal and its gardens also declined. By the 19th century, the British Empire controlled more than three-fifths of India,[44] and assumed management of the Taj Mahal. They changed the landscaping to their liking which more closely resembled the formal lawns of London.[45]

Outlying buildings

The Taj Mahal complex is bordered on three sides by crenellated red sandstone walls; the side facing the river is open. Outside the walls are several additional mausoleums, including those of Shah Jahan's other wives, and a larger tomb for Mumtaz's favourite servant. These structures, composed primarily of red sandstone, are typical of the smaller Mughal tombs of the era. The garden-facing inner sides of the wall are fronted by columned arcades, a feature typical of Hindu temples which was later incorporated into Mughal mosques. The wall is interspersed with domed chattris, and small buildings that may have been viewing areas or watch towers like the Music House, which is now used as a museum.

The main gateway (darwaza) is a monumental structure built primarily of marble, and reminiscent of the Mughal architecture of earlier emperors. Its archways mirror the shape of the tomb's archways, and its pishtaq arches incorporate the calligraphy that decorates the tomb. It uses bas-relief and pietra dura inlaid decorations with floral motifs. The vaulted ceilings and walls have elaborate geometric designs like those found in the other sandstone buildings in the complex.

At the far end of the complex are two grand red sandstone buildings that mirror each other, and face the sides of the tomb. The backs of the buildings parallel the western and eastern walls. The western building is a mosque and the other is the jawab (answer), thought to have been constructed for architectural balance although it may have been used as a guesthouse. Distinctions between the two buildings include the jawab's lack of a mihrab (a niche in a mosque's wall facing Mecca), and its floors of geometric design whereas the floor of the mosque is laid with outlines of 569 prayer rugs in black marble. The mosque's basic design of a long hall surmounted by three domes is similar to others built by Shah Jahan, particularly the Masjid-i Jahān-Numā, or Jama Masjid, Delhi. The Mughal mosques of this period divide the sanctuary hall into three areas comprising a main sanctuary and slightly smaller sanctuaries on either side. At the Taj Mahal, each sanctuary opens onto an expansive vaulting dome. The outlying buildings were completed in 1643.[17]

Construction

The Taj Mahal is built on a parcel of land to the south of the walled city of Agra. Shah Jahan presented Maharaja Jai Singh I with a large palace in the centre of Agra in exchange for the land.[46] An area of roughly 1.2 hectares (3 acres) was excavated, filled with dirt to reduce seepage, and levelled at 50 metres (160 ft) above the riverbank level. In the tomb area, piles were dug and filled with stone and rubble to form the footings of the tomb. Instead of lashed bamboo, workmen constructed a colossal brick scaffold that mirrored the tomb. The scaffold was so enormous that foremen expected it to take years to dismantle.[47]

The Taj Mahal was constructed using materials from all over India and Asia. It is believed over 1,000 elephants were used to transport building materials. Some 22,000 labourers, painters, embroidery artists and stonecutters were used.[48] The translucent white marble was brought from Makrana, Rajasthan, the jasper from the Punjab region, jade and crystal from China. The turquoise was from Tibet and the Lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, while the sapphire came from Sri Lanka and the carnelian from Arabia. In all, 28 types of precious and semi-precious stone were inlaid into the white marble.[49]

According to the legend, Shah Jahan decreed that anyone could keep the bricks taken from the scaffold, and thus it was dismantled by peasants overnight.[50] A 15-kilometre (9.3 mi) tamped-earth ramp was built to transport marble and materials to the construction site and teams of 20 or 30 oxen pulled the blocks on specially constructed wagons.[51] An elaborate post-and-beam pulley system was used to raise the blocks into the desired position. Water was drawn from the river by a series of purs, an animal-powered rope and bucket mechanism, into a large storage tank and raised to a large distribution tank. It was passed into three subsidiary tanks, from which it was piped to the complex.

The plinth and tomb took some 12 years to complete. The remaining parts of the complex took an additional 10 years and were completed in order of minarets, mosque and jawab, and gateway. Since the complex was built in stages, discrepancies exist in completion dates due to differing opinions on "completion". Construction of the mausoleum itself was essentially completed by 1643[16] while work on the outlying buildings continued for years. Estimates of the cost of construction vary due to difficulties in estimating costs across time. The total cost at the time has been estimated to be about ₹ 32 million,[16] which is around ₹ 52.8 billion ($827 million US) based on 2015 values.[52]

Symbolism

Due to the global attention that it has received and the millions of visitors it attracts, the Taj Mahal has become a prominent image that is associated with India, and in this way has become a symbol of India itself.[53]

Along with being a renowned symbol of love, the Taj Mahal is also a symbol of Shah Jahan's wealth and power, and the fact that the empire had prospered under his rule.[54] Bilateral symmetry dominated by a central axis has been used by rulers as a symbol of a ruling force that brings balance and harmony, and Shah Jahan applied that concept in the making of the Taj Mahal.[55] Additionally, the plan is aligned in the cardinal north–south direction and the corners have been placed so that when seen from the centre of the plan, the sun can be seen rising and setting on the north and south corners on the summer and winter solstices respectively. This makes the Taj a symbolic horizon.[56]

The planning and structure of the Taj Mahal, from the building itself to the gardens and beyond, is symbolic of Mumtaz Mahal's mansion in the garden of Paradise.[55] The concept of Gardens of Paradise is extended into the building of the mausoleum as well. Colorful vines and flowers decorate the interior, and are filled in with semi-precious stones using a technique called pietra dura, or as the Mughals called it, parchin kari.[57] The building appears to slightly change colour depending on the time of day and the weather. The sky has not only been incorporated in the design through the reflecting pools but also through the surface of the building itself. This is another way to imply the presence of Allah at the site.[58]

According to Ebba Koch, art historian and international expert in the understanding and interpretation of Mughal architecture and the Taj Mahal, the planning of the entire compound of the Taj symbolises earthly life and the afterlife, a subset of the symbolisation of the divine. The plan has been split into two – one half is the white marble mausoleum itself and the gardens, and the other half is the red sandstone side meant for worldly markets. Only the mausoleum is white so as to represent the enlightenment, spirituality and faith of Mumtaz Mahal. According to the world-traveler Eleanor Roosevelt, the white symbolised the purity of real love.[59] Koch has deciphered that symbolic of Islamic teachings, the plan of the worldly side is a mirror image of the otherworldly side, and the grand gate in the middle represents the transition between the two worlds.

The Taj is also seen as a feminine architectural form, and is thought to embody Mumtaz Mahal herself.[60]

Later days

Soon after the Taj Mahal's completion, Shah Jahan was deposed by his son Aurangzeb and put under house arrest at the nearby Agra Fort from where he could see the Taj Mahal. Upon Shah Jahan's death, Aurangzeb buried him in the mausoleum next to his wife.[61] In the 18th century, the Jat rulers of Bharatpur invaded Agra and attacked the Taj Mahal. They took away the two chandeliers, one of agate and another of silver, which were hung over the main cenotaph; they also took the gold and silver screen. Kanbo, a Mughal historian, said the gold shield which covered the 4.6-metre-high (15 ft) finial at the top of the main dome was also removed during the Jat despoilation.[62]

By the late 19th century, parts of the buildings had fallen into disrepair. At the end of the 19th century, British viceroy Lord Curzon ordered a sweeping restoration project, which was completed in 1908.[63] He also commissioned the large lamp in the interior chamber, modelled after one in a Cairo mosque. During this time, the garden was remodelled with European-style lawns that are still in place today.[64]

Threats

In 1942, the government erected scaffolding to disguise the building in anticipation of air attacks by the Japanese Air Force.[65][66] During the India-Pakistan wars of 1965 and 1971, scaffolding was again erected to mislead bomber pilots.[67]

More recent threats have come from environmental pollution on the banks of the Yamuna River including acid rain[68] due to the Mathura Oil Refinery,[69] which was opposed by Supreme Court of India directives.[70] The pollution has been turning the Taj Mahal yellow-brown.[71][72] To help control the pollution, the Indian government has set up the "Taj Trapezium Zone (TTZ)", a 10,400-square-kilometre (4,000 sq mi) area around the monument where strict emissions standards are in place.[73]

Concerns for the tomb's structural integrity have recently been raised because of a decline in the groundwater level in the Yamuna river basin which is falling at a rate of around 1.5 m (5 ft) per year. In 2010, cracks appeared in parts of the tomb, and the minarets which surround the monument were showing signs of tilting, as the wooden foundation of the tomb may be rotting due to lack of water. It has been pointed out by politicians, however, that the minarets are designed to tilt slightly outwards to prevent them from crashing on top of the tomb in the event of an earthquake. In 2011, it was reported that some predictions indicated that the tomb could collapse within five years.[74]

Small minarets located at two of the outlying buildings were reported as damaged by a storm on 11 April 2018.[75] On 31 May 2020 another fierce thunderstorm caused some damage to the complex.[76]

Tourism

The Taj Mahal attracts a large number of tourists. UNESCO documented more than 2 million visitors in 2001,[77] which had increased to about 7–8 million in 2014.[78] A three-tier pricing system is in place, with a significantly lower entrance fee for Indian citizens and more expensive ones for foreigners. As of 2022, the fee for Indian citizens was ₹50, for citizens of SAARC and BIMSTEC countries, it was ₹540 and for other foreign tourists, it was ₹1,100.[79] Most tourists visit in the cooler months of October, November and February. Polluting traffic is not allowed near the complex and tourists must either walk from parking areas or catch an electric bus. The Khawasspuras (northern courtyards) are currently being restored for use as a new visitor centre.[80][81] In 2019, to address overtourism, the site instituted fines for visitors who stayed longer than three hours.[82]

The small town to the south of the Taj, known as Taj Ganji or Mumtazabad, was initially constructed with caravanserais, bazaars and markets to serve the needs of visitors and workers.[83] Lists of recommended travel destinations often feature the Taj Mahal, which also appears in several listings of seven wonders of the modern world, including the recently announced New Seven Wonders of the World, a recent poll with 100 million votes.[84]

The grounds are open from 06:00 to 19:00 hours on weekdays, except on Friday when the complex is open for prayers at the mosque between 12:00 and 14:00 hours. The complex is open for night viewing on the day of the full moon and two days before and after,[85] excluding Fridays and the month of Ramadan.

Foreign dignitaries often visit the Taj Mahal on trips to India. Notable figures who have travelled to the site include Dwight Eisenhower, Jacqueline Kennedy, Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, George Harrison, Vladimir Putin, Princess Diana, Donald Trump, Justin Trudeau, Prince Charles, Queen Elizabeth, and Prince Philip.[86][87][88][89]

Myths

Ever since its construction, the building has been the source of an admiration transcending culture and geography, and so personal and emotional responses have consistently eclipsed scholastic appraisals of the monument.[90] A longstanding myth holds that Shah Jahan planned a mausoleum to be built in black marble as a Black Taj Mahal across the Yamuna river.[14] The idea originates from fanciful writings of Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a European traveller who visited Agra in 1665. It was suggested that his son Aurangzeb overthrew Shah Jahan before it could be built. Ruins of blackened marble across the river in the Mehtab Bagh, seemed to support this legend. However, excavations carried out in the 1990s found that they were discoloured white stones that had turned black.[91] A more credible theory for the origins of the black mausoleum was demonstrated in 2006 by archaeologists who reconstructed part of the pool in the Mehtab Bagh. A dark reflection of the white mausoleum could clearly be seen, befitting Shah Jahan's obsession with symmetry and the positioning of the pool itself.[92]

No concrete evidence exists for claims that describe, often in horrific detail, the deaths, dismemberments and mutilations which Shah Jahan supposedly inflicted on various architects and craftsmen associated with the tomb.[93][94] Some stories claim that those involved in construction signed contracts committing themselves to have no part in any similar design. Similar claims are made for many famous buildings.[95] No evidence exists for claims that Lord William Bentinck, governor-general of India in the 1830s, supposedly planned to demolish the Taj Mahal and auction off the marble. Bentinck's biographer John Rosselli says that the story arose from Bentinck's fund-raising sale of discarded marble from Agra Fort.[96]

Another myth suggests that beating the silhouette of the finial will cause water to come forth. To this day, officials find broken bangles surrounding the silhouette.[97]

Several myths, none of which are supported by the archaeological record, have appeared asserting that people other than Shah Jahan and the original architects were responsible for the construction of the Taj Mahal. For instance, in 2000, India's Supreme Court dismissed P. N. Oak's petition[98] to declare that a Hindu king built the Taj Mahal.[95][99] In 2005, a similar petition was dismissed by the Allahabad High Court. This case was brought by Amar Nath Mishra, a social worker and preacher who claimed that the Taj Mahal was built by the Hindu King Parmal Dev in 1196.[100]

Another such unsupported theory is that the Taj Mahal was designed by an Italian, Geronimo Vereneo, held sway for a brief period after it was first promoted by Henry George Keene in 1879 who went by a translation of a Spanish work Itinerario, (The Travels of Fray Sebastian Manrique, 1629–1643). Another theory that a Frenchman, Austin of Bordeaux designed the Taj was promoted by William Henry Sleeman based on the work of Jean-Baptiste Tavernier. These ideas were revived by Father Hosten and discussed again by E.B. Havell and served as the basis for subsequent theories and controversies.[101]

As of 2017, several court cases about Taj Mahal being a Hindu temple have been inspired by P. N. Oak's theory.[102][103] In August 2017, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) stated there was no evidence to suggest the monument ever housed a temple.[104] Bharatiya Janata Party's Vinay Katiyar in 2017 claimed that the 17th century monument was built by Mughal emperor Shah Jahan after destroying a Hindu temple called "Tejo Mahalaya" and it housed a Shiva linga. This claim had also been made by another BJP member Laxmikant Bajpai in 2014. The BJP government's Union Minister of Culture Mahesh Sharma stated in November 2015 during a session of the parliament, that there was no evidence that it was a temple. The theories about Taj Mahal being a Shiva temple started circulating when Oak released his 1989 book Taj Mahal: The True Story. He claimed it was built in 1155 AD and not in the 17th century, as stated by the ASI.[105]

Gallery

- Taj Mahal

Eastern view in the morning

Eastern view in the morning Taj Mahal in cloudy weather and its minaret under restoration

Taj Mahal in cloudy weather and its minaret under restoration Western view at sunset

Western view at sunset Taj Mahal through the fog

Taj Mahal through the fog A panoramic view looking 360 degrees around the Taj Mahal in 2005

A panoramic view looking 360 degrees around the Taj Mahal in 2005

See also

- Architecture of India

- Bibi Ka Maqbara, a similar building in the Deccan, Aurangabad

- Fatehpur Sikri, a nearby city and World Heritage Site

- Islamic architecture

- Indo-Islamic architecture

- Inside, a 1968 new-age music album recorded in the building

- List of tallest domes

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

- New 7 Wonders of the World

- Taj Mahal replicas and derivatives

- Wonders of the World

References

Citations

- "Taj Mahal". UNESCO Culture World Heritage Centre, World Heritage List. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- DuTemple 2003, p. 32.

- India tourism statistics 2019 (PDF) (Report). Ministry of tourism of India. p. 107. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- Dehkhoda, Ali Akbar. Dehkhoda Dictionary (online version) (in Persian). Tehran: Dehkhoda Lexicon Institute & International Center for Persian Studies (University of Tehran). Archived from the original on 15 June 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- Wells 1990, p. 704.

- Ahmed 1998, p. 94.

- 1595 to 1872: Bob Allen, Prices and Wages in India, 1595-1930 1873 to 1919: Williamson J., Real Wages and Relative Factor Prices in the Third World 1820-1940: Asia. 2000, Appendix 2 Nominal Wage, Cost of Living and Real Wage Data for India 1873-1939 and Land Prices for the Punjab 1871-1939, 1920 to 1953: Coos Santing, 2007, Inflation 1800-2000, data from OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Economic Outlook. Historical Statistics and Mitchell, B. R. International Historical Statistics, Africa, Asia and Oceania 1750-1993 London : Macmillan ; New York : Stockton, 1998, International Historical Statistics, Europe 1750-1993 London : Macmillan ; New York : Stockton, 1998, and International Historical Statistics, The Americas 1750-1993 London : Macmillan ; New York : Stockton, 1998, 1954 to 2023: Historic inflation India – CPI inflation, Inflation.eu, retrieved 8 July 2023

- "Views of Taj Mahal". www.tajmahal.gov.in. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- Tillotson 2008, p. 14.

- "Definition of Taj Mahal". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- "Taj Mahal definition and meaning". Collins English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- Islamic Culture. Vol. 49–50. 1975. p. 195.

- The Calcutta Review. Vol. 149. 1869. p. 146.

- Asher 1992, p. 210.

- "Taj Mahal: Memorial to Love". Treasures of the World: Taj Mahal. PBS. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- Sarkar 1919, pp. 30, 31.

- "Creation History of Taj Mahal". Department of Tourism, Government of Uttar Pradesh, India. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Chaghtai 1938, p. 46.

- Wayne Edison Begley; Ziauddin Abdul Hayy Desai (1989). Taj Mahal: The Illumined Tomb : an Anthology of Seventeenth-century Mughal and European Documentary Sources. Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture. pp. 13–14, 22, 41–43.

- Chaghtai 1938, p. 146.

- Copplestone 1963, p. 166.

- "Taj Mahal". Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- "World Heritage Sites – Agra – Taj Mahal". World Heritage Sites. Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- "Onion domes, bulbous domes". Stromberg Architectural. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- Ahuja & Rajani 2016, pp. 996–997.

- Bloom & Blair 2009, p. 32.

- "'The Taj!' Exteriors". Official WebSite of Taj Mahal. U.P. Tourism. Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Tillotson 1990.

- "Taj Mahal – A Monument of Love in India". Kristian Bertel Photography. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- "Taj Mahal Calligraphy". Archived from the original on 1 December 2016.

- Koch 2006, p. 100.

- "The Taj mahal". Islamic architecture. Islamic Arts and Architecture Organization. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- "...calligraphy". Treasures of the World: Taj Mahal. PBS. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- "Finest example of Mughal architecture – Review of Taj Mahal, Agra, India". Tripadvisor. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Malaviya 2004.

- Khatri 2012, p. 128.

- Alī Jāvīd 2008, p. 309.

- "The Rauza (Tombs) in the Mausoleum". .taj-mahal.net. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- Begley 1979, p. 14.

- "The plants growing throughout the Taj Mahal complex". India Tourism. Archived from the original on 17 July 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Wright 2000.

- Allan 1958, p. 318.

- Dunn 2007.

- Royals 1996, p. 7.

- Koch 2006, p. 139.

- Chaghtai 1938, p. 54.

- Koch 1997.

- "10 interesting facts about the Taj Mahal". UNIGLOBE. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- Mann, Elizabeth (2008). Taj Mahal. Mikaya Press. ISBN 978-1-931414-44-9. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- "...building the Taj Mahal". Treasures of the World: Taj Mahal. PBS. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Carroll 1973, p. 64.

- "rupees 52.8 billion (dollars US)". WolframAlpha: Computational Intelligence. Wolfram Alpha LLC. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Tillotson 2008, p. 32.

- Kinra 2015, p. 146.

- Koch 2005, p. 140.

- Sparavigna 2013, p. 106.

- Moinifar 2013, p. 133.

- "Views of Taj Mahal". Department of Tourism, Government of Uttar Pradesh, India. 4 December 2020. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Begley 1979.

- Havell 2004, p. .

- Gascoigne 1971, p. 243.

- Swamy 2003.

- "History of Taj Mahal". www.tajmahal.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- admin (19 September 2022). "Taj Mahal – The Symbol of Love – Shah Jahan Mumtaz Mahal". The Indian Chronicles. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- DuTemple 2003, p. 96.

- "Access 360° World Heritage". The National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- "Taj Mahal 'to be camouflaged'". BBC News. 29 December 2001. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- Dowdey 2007.

- "What Really Ails the Taj Mahal?". The Wire. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- "Supreme Court raps Government for its apathy towards Taj Mahal". India Today. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- Jayalakshmi 2014.

- "The Taj Mahal is falling victim to chronic pollution". The Telegraph. 3 December 2010. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "Toxons and the Taj". Frontline. 30 April 1997. Archived from the original on 26 May 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2015 – via UNESCO.

- "Taj Mahal could collapse within two to five years". Fox News. 7 October 2011. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- "India Taj Mahal minarets damaged in storm". BBC News. 12 April 2018. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Deadly thunderstorm damages Taj Mahal". Dawn. 1 June 2020. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "Periodic Reporting Exercise on the Application of the World Heritage Convention" (PDF). December 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015 – via UNESCO.

- "Archaeological Survey of India Agra working on compiling visual archives on Taj Mahal". The Economic Times. 29 November 2015. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- "Timing and Ticket Price to Visit the Taj Mahal in Agra, India". Website of Taj Mahal – Department of Tourism, Government of Uttar Pradesh, India. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Koch 2006, p. 120.

- Koch 2006, p. 254.

- Jaiswal 2019.

- Koch 2006, pp. 201–208.

- "New Seven Wonders of the World announced". The Telegraph. 9 July 2007. Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- "Night Viewings of Taj Mahal". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- "Trump to Diana: The most iconic Taj Mahal photos". BBC News. 24 February 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Bennett, Kate (21 February 2020). "Melania Trump next in long line of first ladies to visit India". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "Trudeau, with family in tow, visits India's famed Taj Mahal". CBC. 18 February 2018. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- Fidler, Matt (25 February 2020). "Taj Mahal posers through the years". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- Koch 2006, p. 231.

- Koch 2006, p. 249.

- Warrior Empire: The Mughals of India. A+E Television Network. 2006.

- "Mutilations in Taj Mahal Myth". Taj Mahal. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- Lahiri 2004, p. .

- Koch 2006, p. 239.

- Rosselli 1974, p. 283.

- Koch 2006, p. 240.

- Writ Petition (Civil) 336 of 2000, P.N. Oak vs. U.O.I. & Ors.

- "Plea to rewrite Taj history dismissed". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- Ali 2014.

- Dixon 1987, p. 170.

- Qureshi 2017.

- "Is Taj Mahal a mausoleum or a Shiva temple? CIC asks govt to clarify". Hindustan Times. 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- Ankit TyagiHarmeet Shah Singh (18 October 2017). "BJP's Vinay Katiyar now calls Taj Mahal a Hindu temple – a 'bee in bonnet' theory that Supreme Court once rejected". India Today. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "What is Tejo Mahalaya controversy?". The Indian Express. 18 October 2017. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

General sources

- Ahluwalia, Ravneet (3 October 2017). "Taj Mahal dropped from tourism booklet by state government". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022.

- Ali, Mohammad (8 December 2014). "Taj Mahal part of an ancient temple: UP BJP chief". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- Asher, Catherine B. (1992). Architecture of Mughal India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26728-1.

- Ahuja, Dilip R.; Rajani, M.B. (2016). "On the symmetry of the central dome of the Taj Mahal" (PDF). Current Science. 110 (6): 996–997. doi:10.18520/cs/v110/i6/996-999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Ahmed, Akbar S. (1998). Islam Today: A Short Introduction to the Muslim World. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85771-380-3.

- Allan, John (1958). The Cambridge Shorter History of India (First ed.). Cambridge: S. Chand, 288 pages.

- Alī Jāvīd, Tabassum Javeed (2008). World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India, Volume 1. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-483-9. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018.

- Begley, Wayne E. (March 1979). "The Myth of the Taj Mahal and a New Theory of Its Symbolic Meaning" (PDF). The Art Bulletin. 61 (1): 7–37. doi:10.2307/3049862. JSTOR 3049862. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S. (1 January 2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195309911.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- Carroll, David (1973). The Taj Mahal. Newsweek. ISBN 978-0-88225-024-3.

- Chaghtai, Muhammad Abdulla (1938). Le Tadj Mahal d'Agra (Inde), histoire et description comprenant en appendice le texte d'un ms. persan sur le Tadj provenant de la Bibliothèque nationale à Paris: thèse pour le doctorat d'Université présentée à la Faculté des lettres de l'Université de Paris, par Muhammad Abdulla Chaghtai (Thesis). Éditions de la Connaissance.

- Copplestone, Trewin (1963). World architecture: an illustrated history from earliest times. Crescent Books. ISBN 978-0-517-35148-2.

- Dixon, Jack S. (1987). "The Veroneo controversy". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 15 (2): 170–178. doi:10.1080/03086538708582735.

- Dowdey, Sarah (5 August 2007). "How Acid Rain Works". HowStuffWorks. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- Dunn, Jerry Camarillo Jr. (2007). "HowStuffWorks: The Taj Mahal". Archived from the original on 13 September 2007.

- DuTemple, Lesley A. (2003). The Taj Mahal. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-4694-8. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- Gascoigne, Bamber (1971). The great Moghuls. Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-00580-7.

- Havell, E.B. (1913). Indian Architecture: Its Psychology, Structure and History, John Murray.

- Havell, E. B. (2004). A Handbook to Agra and the Taj, Sikandra, Fatehpur-Sikri and the Neighbourhood. Calcutta.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jaiswal, Anuja (12 June 2019). "Now, pay fine if you spend more than 3 hrs at Taj". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- Jayalakshmi, K. (11 December 2014). "India: Pollution turning the Taj Mahal brown". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- Khatri, Vikas (2012). Greatest Wonders of the World. V&S Publishers. ISBN 978-93-81588-30-7.

- Kinra, Rajeev (2015). Writing Self, Writing Empire: Chandar Bhan Brahman and the Cultural World of the Indo-Persian State Secretary. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Koch, Ebba (1997). "Mughal Palace Gardens from Babur to Shah Jahan (1526–1648)". Muqarnas. 14: 143–165. doi:10.2307/1523242. JSTOR 1523242.

- Koch, Ebba (March 2005). "The Taj Mahal: Architecture, Symbolism, and Urban Significance". Muqarnas. 22: 128–149. doi:10.1163/22118993_02201008. JSTOR 25482427.

- Koch, Ebba (2006). The Complete Taj Mahal: And the Riverfront Gardens of Agra (First ed.). Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-34209-1.

- Lahiri, Jhumpa (2004). The Namesake. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-547-42931-1.

- Malaviya, Nalini S. (19 March 2004). "Tables with inlay work enhance appeal of your interiors". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Moinifar, Heshmat H. (2013). "Taj Mahal as a Mirror of Multiculturalism and Architectural Diversity in India". Journal of Subcontinent Researches.

- Qureshi, Siraj (2017). "Another court petition challenges Taj Mahal's story as a symbol of love". India Today. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- Rosselli, John (1974). Lord William Bentinck: The Making of a Liberal Imperialist, 1774–1839. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02299-7.

- Royals, Sue (1996). Our Global Village – India. India: Lorenz Educational Press. ISBN 978-1-4291-1107-2. Archived from the original on 13 October 2015.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (Sir) (1919). Studies in Mughal India. Calcutta M.C. Sarkar. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Sparavigna, Amelia Carolina (November 2013). "The Gardens of Taj Mahal and the Sun". International Journal of Sciences.

- Swamy, K.R.N. (13 July 2003). "Perils the Taj has faced". The Tribune (Chandigarh). Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- Tillotson, Giles Henry Rupert (1990). Mughal India. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-87701-686-1.

- Tillotson, G. H. R (2008). Taj Mahal. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03186-9.

- Wells, John C. (1990). Longman pronunciation dictionary. Harlow, England: Longman. ISBN 0-582-05383-8.

- Wright, Karen (1 July 2000). "Works in Progress". Discover. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. Archived from the original on 29 January 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

External links

- Official website of the Taj Mahal

- Description of the Taj Mahal at the Archaeological Survey of India

- Profile of the Taj Mahal at UNESCO

- "Outlying Buildings". Taj Mahal. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

.jpg.webp)