Telangana Rebellion

The Telangana Rebellion popularly known as Telangana Sayuda Poratam (Telugu : తెలంగాణ సాయుధ పోరాటం) of 1946–51 was a communist-led insurrection of peasants against the princely state of Hyderabad in the region of Telangana that escalated out of agitations in 1944–46.

| Telangana Rebellion Telangana Sayuda Poratam | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Indian independence movement | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

1946–1948: 1948–1951: Durras of Hyderabad Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Localised leadership |

| ||||||

Hyderabad was a feudal monarchy where most of the land was concentrated in the hands of landed aristocrats known as Doras in Telangana. Feudal exploitation in the region was more severe compared to others of India; the Doras had complete power over the peasants and could subject them to agricultural slavery. Conditions worsened during the 1930s due to the Great Depression and a transition towards commercial crops. In the 1940s, the peasants started turning towards communism, organised themselves through the Andhra Mahasabha and began a rights movement, catalyzed by a food crisis that affected the region following the end of the Second World War, the movement escalated into a rebellion after the administration and the durras attempted to suppress it.

The revolt began on 4 July 1946, when a local peasant leader was killed in the village of Kadavendi, Warangal, by the agents of a dorra. Beginning in the districts of Nalgonda and Warangal, the rebellion evolved into a revolution across Telangana in response to continued repression by the Nizam Mir Osman Ali Khan and later Kasim Razvi. The Hyderabad State Forces and the police, combined with the paramilitary Razakars, were unable to suppress it and were routed, while the rebel forces went on a successful guerrilla offensive.

The rebels established a parallel system of government composed of gram rajyams (village communes) that caused a social revolution where caste and gender distinctions were reduced; women's workforce participation including in the armed squads increased and the conditions of the peasants significantly improved with land redistribution. At its peak in 1948, the rebellion covered nearly all of Telangana and had at least 4,000 villages directly administered by communes. It was supported by the left-wing faction of the Hyderabad State Congress, many of whom later joined the Socialist Party of India when it was formed by the Congress Socialist Caucus.

The rebellion ended when the military administration set up by the Nehru government unexpectedly launched an attack on the communes immediately following the annexation of Hyderabad to fulfil assurances given by V. P. Menon to the American embassy that the communists would be eradicated, leading to an eventual call for the rebels to lay down arms issued by the Communist Party of India on 25 October 1951.

Background

Situated on the Deccan Plateau in southern India, Hyderabad was a princely state of the British Raj, the second largest and most populous among them.[1] The state had a patrimonial system with the Nizam of Hyderabad as the ruler and the British maintaining complete authority over it.[2] Multiethnic in composition, its 17 districts were divided across three linguistic regions:[3][4]

- Hyderabad-Karnataka consisted of three districts and was populated by Kannada speaking people.

- Marathwada consisted of five districts and was populated by Marathi speaking people.

- Telangana consisted of nine districts and was populated by Telugu speaking people. It contained more than half the population of the state and covered the entire eastern half including Hyderabad city, the capital of the state.

Feudal system

The princely state of Hyderabad retained a feudal system in its agrarian economy. It had two main types of land tenure, diwani (or khalsa) and a distinct category of land called jagir. The lands designated as jagir were granted to aristocrats called jagirdars based on their rank and order, while a portion of the jagir lands were held as the crown lands (sarf-e-khas) of the Nizam. The civil courts had no jurisdiction over the jagir lands which allowed the jagirdars to impose various forms of exorbitant arbitrary taxes on the peasants and extract revenue through private agents. The diwani tenures resembled the ryotwari system introduced by the British in other parts of the country. It had hereditary revenue collectors; deshmukhs and deshpandes who were granted land annuities called vatans, based on past revenue collections.[5] The diwani lands legally held by the government were divided into small sections called pattas registered to occupants who were responsible for the payment of land revenue.[note 1] The registered occupants included peasants who cultivated their own land or occupants who either employed agricultural labourers or rented out the land to tenants.[6] The tenants, called shikmidars, had tenancy rights and could not be evicted on condition that they fulfill land revenue obligations. More than three-fourths of the tenants were tenants at will or asami shikmidars who retained land revenue obligations but did not have tenancy rights. They could become shikmidars after a period of twelve years, though in practice they were evicted within three to four years.[7] The responsibility for registration lay with the deshmukhs and deshpandes. They had access to land records and there was a lack of literacy among the peasants.[8] The system turned them into a hybrid of a feudal lord and a bureaucrat who frequently acquired more lands from the peasants and forced them into the status of tenants at will and landless labourers.[5] The individual deshmukhs and deshpandes had multiple villages under their domains and appointed personal officials (seridars) to manage each village.[8] The jagirs and diwani tenures constituted around 30% and 60% respectively of the territory of Hyderabad State.[5]

The feudal system was particularly harsh in the Telangana region of the state. The powerful deshmukh and jagirdar aristocracy, locally called durras, additionally functioned as money lenders and as the highest village official. The durras employed variants of the jajmani system called vetti and baghela which forced families of peasants into bonded servitude by means of customary and debt obligations. [9] The power of the deshmukhs was augmented with additional hereditary positions such as patel, patwari and mali patel which granted them various political, judicial and administrative functions.[8] They could determine taxation rates and managed land surveying; peasants had to offer nazaranas in the form of cattle, crops and money to prevent prejudiced treatment.[10] The jagirdars were predominantly Brahmin, supplanted by the emergence of velama and Reddy deshmukhs. Markets and major businesses were controlled by Marwadi and Komti durras.[9] In contrast, the bulk of the peasantry came from disparate caste backgrounds and even included Brahmins, Reddys and Komtis.[11][12] The tribals such as Chenchus, Koyas, Lambadis, Konda Reddis, and untouchables like the Malas and Madigas were among the most impoverished and particularly vulnerable to severe forms of exploitation by durras, including agricultural slavery.[9] Anti–slavery legislations were largely unenforced in the British Raj, and officials were instead reprimanded for mentioning slaves in documentation.[13]

Telangana had a higher concentration of land in the hands of a small group of landed magnates than the other regions. They owned vast tracts of lands covering several villages and thousands of acres. The land concentration was most pronounced in the districts of Nalgonda, Mahbubnagar and Warangal. They later became the epicenter of the insurrection.[5] The peasants were largely dependent on affluent urban interests, mostly composed of Marwadis, Komtis, Brahmins and upper caste Muslims, who controlled the centralised markets in Telangana. Land alienation continued to increase between 1910 and 1940 as more land was passed either to urban interests and aristocratic durra landlords or to Marwadi and Maratha sahukars (money-lenders). Peasants with small landholding were pushed into landless agricultural labour or tenancy at will. Irrigation facilities were introduced from the late 19th century and a greater portion of the land transfer occurred on lands with these facilities. The system of subsistence farming gave way to commercial crops, strengthening the hold of traders and sahukars over the peasants, which was particularly worsened during the Great Depression. The period saw the rise of a section of well-to-do pattadars (landholding peasants) who began employing landless labourers of their own, though it did not change the landlord–tenant relations in the region to any significant degree. The landholding peasants too were severely affected after the depression.[12]

Communist mobilisation

| Part of a series on |

| Communism in India |

|---|

|

|

|

Communists had been active in the Telugu speaking Godavari–Krishna delta region of the neighbouring Madras Presidency since 1934 and largely organised through peasants organisations such as the Andhra Mahasabha (Madras), the All India Kisan Sabha and the Indian Peasant Institute.[14] The first incursion of the communist movement in Telangana occurred in the Madhira–Khammam area of Warangal district, through peasants who had settled down at the Wyra and Paleru irrigation projects, and had relatives in Coastal Andhra.[note 2] The first communist organisations were established in Warangal and Nalgonda districts through the efforts of Chandra Rajeswara Rao, a peasant working in Mungala.[note 3] The Regional Committee of the Communist Party of India in Telangana was established under the leadership of Pervaelli Venkataramanaiah in 1941.[15]

The students' movement contributed significantly to the growth of the communist movement, disillusioned with Gandhian satyagraha politics. Having gained experience through the Vandemataram protests, a number of radical progressive student organisations were established which eventually merged to form the All Hyderabad Students Union in January 1942. Devulapalli Venkateswara Rao, a former student agitator during the Vandemataram protests, was instrumental in building up the Communist Party in the districts of Warangal and Nalgonda. The nationalist, progressive and secular intelligentsia in the city of Hyderabad turned towards political radicalism as well, through the influential Naya Adab (New Salute) which promoted communism in literature,[note 4] and through the Comrades Association initially formed in reaction to the growth of communal sectarian organisations.[note 5] The association became communist under the leadership of Raj Bahadur Gour and Makhdoom Mohiuddin.[15]

Andhra Conference

In the meantime, the Andhra Conference, which was a cultural-literary forum acting as a front organisation for the Hyderabad State Congress, was overtaken by communists. It recruited students from colleges[14] but was controlled by a conservative liberal and moderate leadership over whom the Hindu durra aristocracy had a strong influence and who advocated restraint, opposing activities against the "law and order" of the state.[16][17] Following the withdrawal of a satyagraha movement for constitutional reforms in 1938–39 as a result of instructions of the national leadership,[14] the Congress was largely discredited for its younger left-wing members.[note 6][18] Convinced that the expulsion of the Nizam along with all the elites was a necessity for effective democratic gains,[19] the left-wing faction decided to fight the feudal system, began embracing communism and started building up the organisation in the villages from 1941 onwards. They reduced the enrolment fee by one-fourth, encouraged participation by the landless and impoverished sections of the population. They took up peasants' causes such as the abolition of vetti, prevention of rack-renting and eviction of tenants, occupancy (patta) rights of cultivating tenants and reduction in taxes, revenue demands and rents, among others.[14][16]

The Andhra Conference, previously seen as a durra's organisation, grew in popularity among the peasants and started being referred to as the Andhra Mahasabha (AMS) in Telangana.[14] Prominent feminists disillusioned with the Congress who formed the Mahila Navjeevan Mandali in 1941, also joined the AMS and eventually became members of the Communist Party by 1943. Venkateshwara Rao directly recruited disillusioned Congress members and sympathisers into the Communist Party during the same period.[15] Initially faced with opposition from the moderate leadership, landlords organisations such as the Agriculturalists Association and through heavy political repression from the government,[16] the AMS was slowly transformed into a militant mass organisation opposed to the Nizamate with a coalition of peasants, the working class, the middle class and youths as its members.[14] The process was completed in the 1944 Bhongir session of the AMS when two young communists, Ravi Narayan Reddy and Baddam Yella Reddy were elected as the president and secretary.[14][20] The moderates expecting a rout, had resigned from their offices, boycotted the election and later formed a marginal splinter organisation, giving the communists free rein over the primary AMS.[21][20] Arthur Lothian, the Resident at Hyderabad took note of the development in October 1943 and began directly intervening in state action with regard to the communists from thereon.[22]

Agitations of 1944–46

Between 1944 and 1946, the communist movement became widespread in the Telangana countryside. The Andhra Conference controlled by communists substantially increased its membership in the districts of Nalgonda, Warangal and Karimnagar. The movement formed a class alliance between disparate caste groups, the middle peasantry with small landholdings and the rural poor and landless labourers. Numerous villages were enmeshed with communist organisations. Agrarian radicalism was heightened and a mass movement developed with a series of agrarian agitations against the durra aristocrats beginning in 1944.[14][20] The agitations were non-violent and employed tactics such as non-cooperation, withdrawal of services and refusal to pay technically illegal taxes, usually demanding the implementation of existent laws which were unenforced.[20][23] The demands also included the Andhra communists' call for the breakup of Hyderabad State and the formation of Visalandhra, an unified Telugu speaking state composed of Telangana and the Andhra region of the Madras Presidency, in line with the Communist Party of India's demand for the linguistic reorganisation of states.[24] The presence of large organised groups within the villages intimidated the durras and the administration. The private militias of the landlords and the police were sent to conduct violent attacks on the agitators with greater frequency as the movement went on.[23] Hyderabad State passed a legislation for minimum tenurial security in 1945, which only worsened conditions as landlords resorted to frequent mass evictions to prevent accrual of tenancy rights.[12] The agrarian distress was further aggravated by rising prices and food scarcity after the Second World War.[14]

Rebellion

Spontaneous uprising

.jpg.webp)

The post–war economic distress and political developments played a catalytic role in a feudal system already conducive for an uprising.[14] The village level agitations against the aristocratic durra landlords escalated into an insurrection.[note 7] The influence of the communists in Nalgonda and Warangal districts had become so strong by early 1946 that the administration, including the Nizam's firmans (writs), was unable to function in large areas. The expansion of the movement in these areas was facilitated by the presence of estates with thousands of acres.[note 8] The first militant action occurred with a few instances of land seizures from the estates of durras in response to eviction of Lambadi tenant cultivators for non-compliance with additional taxation and demands of vetti forced labour. The village level communist sanghams (organisations) during the 1944–46 agitations had laid down demands for better wages, disallowance of vetti and baghela slavery, evictions, exorbitant taxation and refusal of a new mandatory post–war grain levy.[25]

One major incident on 4 July 1946 marked the beginning of the rebellion; a procession of over 1,000 peasants was fired at by the men of Vishnur Deshmukh in Kadavendi village of Warangal district,[note 9] Doddi Komarayya who was the leader of the local sangham was killed and a number of others severely wounded. The group proceeded to and set fire to the residence of the deshmukh before they were dispersed by the arrival of a contingent of armed police.[26][25] In the following days, 200 acres of land in a neighbouring village were seized from the deshmukh's estate and redistributed by the peasants. The incident sparked a spontaneous movement where groups of villagers would go from one village to another, people would drop out and return to their village after coming some distance, while others from the villages they passed through would take their place and keep the movement going. In each village, they formed drawn out congregations upon their arrival to discuss prevalent local issues and relations with the durra of their area.[26] By the end of July, around 300–400 villages in the districts of Warangal, Nalgonda and Khammam experienced militant action by peasants against the local estates and officials.[note 10] In August 1946, the press wing of the Communist Party of India announced that the villages were under the control of the peasants and launched a national campaign to rally support for the rebellion, publicising the demands of the peasantry and highlighting the feudal exploitation and brutality.[25]

Peasants continuously resisted extortive action from officials and other agents, and refused to perform vetti labour. Small landholders refused to hand over paddy crops for the required levy, and landless labourers and tenants continued to occupy lands from which they had been evicted.[27] The durras sent their private militias to prevent the seizure of their lands, but they were few in number and too poorly armed to contain mass unrest.[28] Unable to control the villages, the durras started fleeing to safer regions, resorted to litigation, and relied on the state police and their private militias to suppress the rebellious peasants.[25][28] The villages adopted a strategy of active defense in response to violent attacks by private militias and the state police. Village level organisations developed a signals network to inform other villages of the position of approaching state security forces and villagers adopted the tactic of gathering en masse armed with slingshots, stones and sticks to ward off reconnaissance units and smaller raiding parties.[23] The rebels had neither the firearms nor the training to use them. The durras, their agents and local officials became fearful of visiting their own estates or jurisdictions which were known to be established strongholds of the communist rebels without paying "protection taxes" themselves.[25]

The Andhra Conference was banned in October 1946 and the police had begun arresting communists and sympathisers throughout the state. Hundreds of Communist Party activists were arrested, and the number of police units assigned to the rebellious regions was increased exponentially.[23][27] The frequency of raids increased through 1946, but during their attempts at arresting communist activists known to the police, crowds of hundreds would gather to obstruct them. The administration started assigning units of the Hyderabad State Forces to assist the police.[23] Some of the villages formed ad hoc volunteer forces for defense.[27] On 16 and 17 November, military personnel killed three villagers and wounded eight others in two raids on the villages of Patha Suryapet and Devarupal. On 27 November, in retaliation for the killing, a police convoy escorting arrested communist activists was ambushed successfully; four police personnel were killed, and the prisoners released.[23]

Following the ambush, the police and military forces began attempting to arrest entire villages and by December, the Suryapet prison alone was holding 600 prisoners. The military crackdown increased in December, resulting in even-heightened militancy; the sangham earlier known as chitti sangham due to their distribution of chittis (receipts), common after the enrolment fee for AMS was reduced, started being known as the lathi sangham for their distribution of lathis (heavy sticks or batons) in this period.[23] By the end of 1946, the police had reported 156 cases of assault by peasants and four major police–peasant battles had occurred, but neither the actions of the military, the police nor the private militias were able to dislodge the communists. Most of the confrontations occurred in the Suryapet and Jangaon taluqas of Nalgonda district; pockets in Khammam, Karimnagar, Nalgonda and Warangal districts had fallen under rebel control,[27] while 4,000 army troops were deployed in Nalgonda district.[29]

The military, equipped with modern firearms, made it much harder for the rebels to operate and the movement became more clandestine in the presence of military camps near their villages; the Andhra communists in the Madras Presidency initiated dialogue with the rebels in preparation for open warfare with the Hyderabad State. Meanwhile, the military camps were withdrawn in January 1947 after a period of absence of any visible disturbances.[30] Despite some instances of armed confrontations, the peasants uprising was spasmodic in their actions and lacked any systemically planned offensives in the initial period. It had begun as a spontaneous upsurge where the organised Andhra Mahasabha and Communist Party acted primarily in an auxiliary capacity.[27]

Reactions

The Hyderabad State Congress was divided into two factions of moderates and leftists since 1938–39. While the left-wing members of the Andhra Conference had gravitated to the Communist Party, those in Maharashtra Parishad in the Marathawada region of Hyderabad State had aligned themselves with the Congress Socialist Caucus, influenced by their presence in Bombay Presidency.[note 11][31] In late 1945, the Indian National Congress had adopted the policy of expelling all communists from its organisations. It convened the All India States Peoples' Conference (AISPC) containing delegates of regional organisations which boycotted the predominantly communist Andhra Conference and instead invited the marginal splinter organisation formed by the moderates. The socialists had protested against the policy, leading to further friction with the moderates in Hyderabad.[note 12][32]

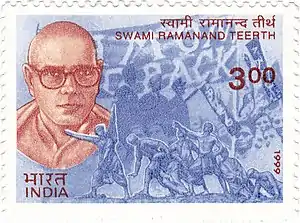

At the onset of the rebellion, and in light of post–war negotiations between the Congress and the British administration, the Nizam of Hyderabad legalised the Hyderabad State Congress in July 1946. The three front organisations — the non-communist Andhra Conference, the Maharashtra Parishad and the Karnatak Parishad were merged, and a provincial working committee was formed; 164 delegates from the three organisations voted in an election for the president of the committee. The socialist candidate Swami Ramananda Tirtha from the Marathawada delegation won against the moderate Burgula Ramakrishna Rao from the Andhra delegation by a narrow margin of three votes. The moderate–left divide persisted with the moderates, mostly affluent lawyers with durra backing, refusing to budge and eventually reaching a crisis point over their position with respect to the communists following the Nizam government's military crackdown on the peasants in late 1946.[32]

In November 1946, the two factions sent separate fact finding teams to Suryapet, led by Tirtha and J. Keshav Rao respectively. Tirtha's group searched for police atrocities while Rao's group searched for reasons to condemn the communists. Tirtha praised the actions of the communists. The leftist faction wanted to not only admonish the government for repression but also convert the party into a more militant mass movement. They were prevented from doing so by the moderates, who were adamantly opposed to any further move to the left. The working committee drafted three resolutions demanding the government end their repression in Nalgonda, lift the ban on the Communist Party and cease criticising the communists for a sectarian approach towards the Congress. The moderates were dissatisfied with it, filibustered it, and did not allow it to pass.[note 13] The State Congress stopped functioning because of the consequent resignation from the left and mediation with the national leadership until March 1947. The left issued a statement denouncing the "barren constitutionalism" of "feudal elements" in the State Congress.[32]

Wilfrid Vernon Grigson, Revenue and Police Minister for the Viceroy's Executive Council, conducted his own investigation in December and reported that the peasants had legitimate grievances and that it was not communist propaganda as previously assumed. The report stated that raiding villages and arresting communists would not succeed in stopping attacks on government officials without an administrative overhaul in the princely state, which according to him the Nizam's officials were incapable of conducting.[23] The AISPC passed a resolution on 27 December condemning the activities of both the government and the communists, based on a report from their president, Dwarkanath Kachru, who had arrived in Hyderabad to conduct his own investigation. In a private letter, Kachru wrote to Tirtha that despite their official stance, the grievances of the peasants were genuine such that "no organisation worthy of its name could put up with" and admitted the communists had simply outflanked them through their mass mobilisation. The activities of the Congress in the state were being marginalised as the conflict between the Nizam's government and the communists engulfed Telangana.[32]

Communist–Left Congress alliance

In February 1947, the British administration announced the transfer of power to the Indian leadership and gave the princely states the option of either joining India or Pakistan or becoming independent. The Nizam of Hyderabad, the Muslim aristocrats and the Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen wanted Hyderabad to become an independent state but the vast majority of people wanted the state to merge with India in hopes of political freedoms and participation in self-government. The Communist Party added merger with India into its list of demands and aligned itself with the Indian National Congress which had started pressuring the Nizam to accede.[33] In March 1947, the working committee of the State Congress was restored and Swami Ramananda Tirtha was reelected with a wide margin of 751 to 498 votes against B.G. Rao, enabling him to completely exclude the moderates. He praised the communists for their revolt and suggested the incorporation of a more revolutionary policy for the State Congress.[34]

The Congress went on satyagraha seeking the merger of Hyderabad with India and the State Congress under Tirtha launched a civil disobedience campaign. The communists joined up with Congress workers in their agitation although they held reservations over the effectiveness of Gandhian methods. Due to the organisational weakness of the Congress, most of the Congress agitation in Telangana especially in the rural areas was carried out instead by communists, the police were unable to differentiate between the two and assumed that they had entered into a league.[34] In the urban areas, communists and Congressmen held joint meetings and demonstrations which provided material benefits to the rebels in the countryside.[35] The general understanding among the communists was that the "rightist congressmen" were backed by the durras and opposed to any form of alliance with them while the "leftist congressmen" wanted an unification with the Communist Party but were too irresolute and timid to carry it forward.[34]

The communists started disassociating with the satyagraha as a consequence of incorporation of Gandhian ethics in the agitations, one key point of discontent became the symbolic cutting down of toddy trees as Gandhian ethics prohibited toddy drinking. The symbolism lay in the toddy plantations also being a major source of revenue for the state but toddy trappers who were subjected to untouchability, were a significant section of the communist activists and base of support, and relied on toddy for their livelihoods.[36] Some degree of co-ordination continued to occur especially due to increase in police repression and the agitations becoming interspersed with instances of violent confrontations. One major incident occurred in Warangal district where a crowd of 2,000 armed with spears and lathis stormed a police station and released two Congress workers who were being subjected to torture, in the process killing an inspector and injuring several policemen.[34] Another occurred within Hyderabad city when a group of agitators burned down the residences of the British Police Minister and the president of the Executive Council of Hyderabad.[37] In Nalgonda, the epicenter of the rebellion, the communists toured across the district, releasing and redistributing grains hoarded in markets and storages, burning down checkpoints on the border and the records of officials and sahukars in the villages, while raising Indian flags in those locations.[30]

Rise of Kasim Razvi

Meanwhile, the Ittehad was spreading sectarian propaganda and attempting to promote fanaticism among Muslims, along with the Arya Samaj and the Hindu Mahasabha attempting to do the same with Hindus in reaction to it. The situation created widespread fear and uncertainty, leading to political instability and a sudden deterioration of law and order across the state.[33] The Nizam, who had isolated himself from the common population and their politics for years, perceived himself to be surrounded by a hostile Hindu population and started to rely increasingly on the Ittehad for support. The leadership of the Ittehad had by then passed to Kasim Razvi, a small-time lawyer from northern India who had supported the Pakistan movement and wanted Hyderabad to become a refuge for Muslims in the south.[38] Gradually the Ittehad under Razvi was able to wrestle control over the Nizam government and was managing its day-to-day functioning. Razvi formed a paramilitary wing for the Ittehad called the razakars. They were deputed alongside the police and grew to 150,000 men, double the police force itself, contributing significantly to public disorder and a complete collapse of civil authority as they embarked on a campaign of political repression.[36][38]

Hindu–Muslim tensions and communal violence in Hyderabad reached its highest point upon Indian Independence.[33] The razakars grew to 200,000 men by the end of August with the recruitment of Muslim refugees from India who had arrived in Hyderabad on the invitation of the Ittehad.[29] The Congress agitations also peaked with a complete shutdown of the state accompanied by flag hoisting, meetings, processions and protests on 7 and 15 August. Tirtha was arrested in mid-August and violent repression of agitators continued to increase over the following period. The Congress leftists of Hyderabad under a new leadership,[note 14] organised themselves through the Committee of Action, which set up camps outside the state and started conducting armed raids into Hyderabad. The camps were allowed by the Home Ministry of India, now under Vallabhbhai Patel and reluctantly approved of by Mahatma Gandhi. The moderates were completely opposed to the armed raids and excluded from the committee.[39] In the following year, the Congress socialists would split from the party under the leadership of Jayaprakash Narayan to form the Socialist Party of India, taking with them much of the leftists of the Hyderabad State Congress.[40]

Escalation and territorial expansion

The crisis of authority in Hyderabad had enabled the influence of the rebels in the countryside to expand rapidly. They set up a parallel administration composed of gram rajyams (village communes) in the areas that came under their control.[41] This parallel administration provided more stability and became a refuge from the violence in the rest of the state.[29] Roving bands of razakars active across Hyderabad to quell agitations were instructed by the government to protect the durras and suppress the communists in Telangana after the withdrawal of the British. Initially attached to police and military forces, the razakars had come to supersede them when the Ittehad assumed power and started operating independently of the state forces. They plundered and looted villages, killed and arrested people on suspicion of being potential agitators and employed rape and torture to quell villages into submission.[29][36] The communists, who had previously relied largely on defensive measures and unarmed resistance, began to openly endorse offensive warfare. The national leadership of the Communist Party officially approved armed rebellion in September 1947.[39]

Volunteer squads called dalams were organised by the communes. They were joined en masse by villagers frustrated with police, military and razakar atrocities, particularly in the districts of Nalgonda, Warangal and Kammam which were communist strongholds.[41] The Communist Party was better organised in the neighbouring Andhra region of Madras State (previously Madras Presidency) and was sending arms, supplies and volunteers into Telangana. This considerably bolstered the organisational, tactical and logistical capabilities of the rebels, transforming the peasants uprising into an organised rebellion.[29] Arms were acquired through black market purchases at increased prices in Telangana and from the estate agents and local government officials by theft and force.[30] The rebels who were equipped with firearms went on guerilla warfare targeting infrastructure, supplies and garrisons of the government and the estates of the durras.[29] Organised mobs were assigned to lower risk targets such as the forest department and offices of village officials, and would burn down their records, take away their lathis and grain stocks. In December, the armed assaults became excessively frequent, the police recorded 45 attacks on major targets within the span of 11 days in Warangal and Nalgonda districts.[39]

In response, the government authorised the police, the military and the razakars to indiscriminately target entire villages for harbouring sympathies for the sangham (communists) or the Congress. The attacks involved reprisals in which the entire population of some villages was killed. There was widespread use of torture against villagers and rape against women as a terror tactic. The extreme measures employed by the state forces pushed otherwise skeptical people in the peripheral areas of the rebel dominated territories to be drawn towards the communists and the rebellion.[39] In some cases, the razakars who the government was unable to control attacked the estates of the durras themselves and plundered them. Consequently, some of the durras entered into agreements with the communes to supply them with resources and abide by their governance in exchange for protection from the razakar bands.[29] The reprisals made the communes strengthen their organisation and co-ordination. The Andhra and Telangana communists set up joint revolutionary headquarters at the Mungala estate, constituting an enclave of Hyderabad State within Krishna district of Madras State.[41] By early 1948, much of Telangana was beginning to rebel in an all-out revolution as more of the rural poor and the peasantry organised themselves under the communists and took up arms against the durras and the Hyderabad State. This triggered a large-scale displacement of durras who fled to the cities, abandoning their private militias and properties. The communist influence was chipping away at the entire social hierarchy with a quasi divine Nizam at the top since the early 1940s, and had eventually enabled the mass uprising to occur.[42]

The rebels suffered from a persistent shortage of modern firearms and had to constantly rely on raids to gain more.[30] As a consequence they were severely outnumbered as the communes refused to deploy more recruits as they were unable to arm them. Despite the shortages, the rebel forces were highly motivated, being entirely composed of volunteers, increasingly ideological and antagonised by years of repression.[42] The rebels were also better adjusted to the terrain and shaped their organisation along the lines of geography and the strategic considerations of guerrilla warfare as they built it from the ground up. This made them much more effective in terms of tactics and logistics. The rebel forces were organised into two categories — garrisons consisting of village dalams who would continue their civilian lives while maintaining hidden arms, and mobile guerrilla dalams who would become full-time operatives and engage in offensives across large distances.[43] The revolutionary headquarters in Mungala became a key source of supplies, arms, literature and organisers as they were smuggled in through the border. Some demobilised war veterans also joined the communists during this period.[41]

In contrast, state forces and the paramilitary razakars lacked co-ordination; the former were demoralised as a consequence of the induction of the latter and having to serve in a subordinate role to them.[29] The rising tensions between the Dominion of India and Hyderabad State made it more difficult for the government as they had to deploy more troops at the frontiers.[44] One critical advantage the government forces had was in terms of transportation. They could use trucks, jeeps and railways to move troops quickly through the few hard bed roads and railway lines that existed in the region while the rebels were largely restricted to foot. Even captured vehicular transportation was not useful to the rebels, as they could not operate them clandestinely, nor did they possess heavy armament like artillery to engage in conventional warfare. To mitigate this advantage, the rebels dug trenches around the villages and roads were either blocked, breached or had planks with nails placed on them. The military would often respond by forcing a group of villagers to refill the trenches, shooting some of them while they worked on it. On 26–27 February, the rebels conducted a major operation with twenty simultaneous co-ordinated attacks on infrastructure targets including important telecommunication facilities, bridges and sections of railway tracks which paralysed the transportation and communication capabilities of the government forces from thereon.[45]

The rebels went on a successful campaign of territorial expansion and effectively routed the government forces by mid-1948. Much of the Telangana countryside came under their control, covering the entirety of Nalgonda, Warangal, Khammam and Karimnagar districts, more than half of Medak and Adilabad districts and a significant portion of the remaining three districts of Telangana namely, Mahabubnagar, Hyderabad and Nizamabad. In Adilabad, Medak and Karimnagar, the Tirtha Group of the Congress had established some bases that defected towards the communists.[46][47] Around 16,000 square miles (41,000 km2), covering 4,000 villages, were being directly administered by communes. The rebel forces had reached a peak with 10,000 troops in garrisons and 2,000 in guerrilla forces. There were an additional three to four million active workers and non-combatant supporters of the rebel forces.[48] In August 1948, the number of razakars stood at 100,000 men even as it recruited 30,000 more in January, down from 200,000 in September 1947. They were increasingly sent by the government to engage with the communists as the rebellion expanded across Telangana, but they proved to be ineffective against them.[29][41] In turn, the razakars became the victims of torture as retribution for their past atrocities, which continued until the communes and sanghams prohibited and eventually banned such activities, declaring them to be primitive.[49]

Decline of the insurrection

In September 1948, the Dominion of India launched a military intervention for the annexation of Hyderabad.[50][51] The intervention officially described as a "police action" was justified on the grounds of ending the undemocratic feudal regime of the Nizam and the razakar repression enabled by him.[52] Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru had stated in a press conference the government's policy towards the communists would depend on how they respond during and after the intervention.[53] The comment was misleading as the government was making preparations to liquidate the peasant communes and restore the durra aristocrats regardless of their response. Internally, the communists were described as the primary target rather than the Nizam and the razakars.[53][54][55][51] V. P. Menon had briefed the American embassy about the intervention and promised them that the communists would be eradicated in return for their support in justifying the military action to the international community. The Home Ministry under Vallabhbhai Patel favoured military intervention as it would enable them to deploy military personnel in Telangana. They had initially stalled the intervention for over a year, despite ongoing razakar atrocities because it was feared that an invasion would allow the communists to strengthen their position. Menon wanted the rebel administration to be dealt with through military courts rather than by civil authorities.[50]

The Indian Army marched into Hyderabad State on 13 September and the already demoralised Hyderabad State Force, the police and the razakars surrendered within a week after minimal resistance.[56] This military intervention was perceived by the peasant communes as a positive development and not as an attack on them. The villagers believed the army was helping them defeat the Nizam's government. They launched a final parallel assault against the remaining military camps of the state forces, outposts of state agents and garrisons in durra estates, accompanied by victory celebrations.[53] The rebels came across large stores of arms and ammunition during the assault. Many of them were handed over to the army after their objectives were accomplished, as the peasants returned to their villages with the belief that the armed conflict was over.[57] The commanding officer selected for the invasion was Major General Jayanto Nath Chaudhuri, who was also a zamindar aristocrat from West Bengal.[58] He set up a military administration after the Nizam's capitulation, banned the Communist Party, and immediately launched a military offensive against the peasant communes.[54][59] The deshmukhs and officials returned as the redistributed lands were to be confiscated and granted back to their original owners.[57]

The military administration did not induct any local police personnel or civil servants, including those affiliated with the Hyderabad State Congress, who were sidelined. Vallabhbhai Patel distrusted them and justified it with the claim that they had a partisan character.[60] They deployed officials and personnel from outside the state, as it was feared that locals might be apprehensive of conducting violence against their own and might even be covert communist sympathisers. Chaudhuri also issued a warning to the police personnel from outside the state about falling under communist influence.[57] The administration orchestrated an anti–communist witch hunt in the state, attempting to arrest any and all communists. There was widespread use of torture against those suspected of harbouring information and the military personnel occasionally conducted indiscriminate arrests and mass shootings against villagers in Telangana.[61][62] Meanwhile, the Nizam was not prosecuted and instead was made the Rajpramukh of Hyderabad State for a period of time.[63] Kasim Razvi was arrested, tried and jailed but soon released and forced to migrate to Pakistan.[64] The military administration actively promoted feudal restoration in Telangana.[65]

The offensive sent the peasant communes and the Communist Party into disarray, causing divisions within them.[66][67] Some of them, including Ravi Narayan Reddy and the former general secretary Puran Chand Joshi, among other veteran party leaders wanted to abandon the armed rebellion and attempt to employ legal pathways to stop the repression to continue their movement, while others antagonised by the actions of the administration wanted to continue an armed guerrilla struggle against the military. Some, including the new general secretary Bhalchandra Trimbak Ranadive, even advocated for escalating the rebellion into a national revolution. Both sides exchanged accusations, denouncing each other as "right wing reformists" and "left wing adventurists".[68][69] The government used this to its advantage, as they were occasionally able to coerce former participants into becoming informants.[62][70] The urban population, unaware of the events in the countryside, had supported the intervention and were convinced by the government and with the help of various statements made by revolutionaries against the Congress, that they were indulging in an unnecessary peasants' partisan warfare after the annexation.[52] On the other hand, the division weakened the communists. Many of the peasants had abandoned the rebellion, especially those from the middle and richer peasantry, some of whom were dissatisfied with the latest land ceiling and who used to provide important contacts and financial support.[67] Despite the desertions, most of the peasants remained sympathetic towards the guerrillas who had decided to keep fighting, and refused to cooperate with the police.[57]

In December 1948, the administration began a large-scale counterinsurgency campaign designed to frighten villagers into not assisting the guerrillas. The States Department sent Captain Nanjappa to act as the Special Commissioner of Police for the operation. Nanjappa ordered indiscriminate arrests, burning down of entire villages where land redistribution had occurred and extrajudicial killings of suspects after capture.[71] Around 2,000 peasants, armed and unarmed, were killed and 25,000 arrested by the end of August 1949.[54] The communes were dis-established and the former durra estates restored in their respective areas. The guerrillas had to retreat into the dense forests of the Godavari Basin and to the forests across the Krishna River in the Nallamala Range, with the support of the Koya and Lambadi tribals respectively.[63][72] The landless and impoverished peasants, which included most of the tribals and untouchables, formed the backbone of the rebellion.[73] The guerrillas adopted even more clandestine tactics; the size of individual squads was reduced to five from ten. They started leading civilian lives among the rural population without readily available arms, depended on intermediaries for communication and occasionally organised to conduct operations. The government adopted the strategy of the Briggs Plan in response; tribal communities were evacuated en masse and placed in large detention camps but guerrillas with widespread support from the locals continued to be able to operate and remain supplied.[61]

De-escalation

The military force, with its high morale and modern equipment, had forced the Nizam and the razakar to surrender within weeks. Despite this, they were unable to suppress the poorly armed peasants for three years.[74] Nehru was concerned with the continued military rule in the state imposed by Patel; civil authorities were introduced in the state after 16 months of military administration.[75] Land reform measures such as the enactment of the Jagirdari Abolition Regulations and setting up of the Agrarian Enquiry Committee were introduced to contain the popularity of the communists. This somewhat reduced the power of the durras in the process.[76] In 1950, the Constitution of India came into force and the dominion became a republic. Fearing the loss of credibility as a democratic government and with the understanding that further repression would only popularise the communists, the Congress administration started making reconciliatory gestures towards the Communist Party from early 1951. There was increasing distrust of the Congress in the state as information from the Telangana countryside was spreading.[67] The leftist congressmen involved in the earlier agitations against the Nizam had started being harshly critical of the government, referring to brutal and unjust repression.[75] There were also ongoing student and labour agitations since 1948–49 in the urban areas.[77]

Meanwhile, Ranadive, who had become the general secretary in 1948 and adopted the policy of continuing the rebellion, was replaced by Chandra Rajeswara Rao in 1950. Opinions critical of the continuation rose through the year. Puran Chand Joshi was aggressively campaigning within the party for withdrawal of the rebellion.[78] In April 1951, Acharya Vinoba Bhave spoke with a number of Communist Party leaders in detention and was able to secure the release of a large number of them.[67] The guerrillas, who maintained a sophisticated courier system for communications and had made enormous sacrifices for the rebellion, were eventually convinced by the party to accept the continuation of armed struggle was a mistake. The rebellion was on the defensive, restricted to its remote safe havens in the forests and had no hopes for regaining lost ground.[79] In the plains, the peasants had also started frequent agricultural strikes and agitations since the dissolution of the communes.[80] The party attempted to negotiate with the Congress to retain some of the gains made by the peasantry by sending a three-man team to Hyderabad and in anticipation of taking the electoral route in the 1951–52 elections, the first ones to be held in independent India and with universal adult franchise. The demands included a halt on all land evictions, withdrawal of the military and release of all detained communists. These were rejected by the Congress, but the communists decided to call off the rebellion regardless.[81]

On 25 October 1951, the Central Committee of the Communist Party officially declared the end of the rebellion.[82] In the state election and national elections, communist leaders, who were formerly part of the rebellion, were elected from almost all rural constituencies they contested in Telangana;[83] Ravi Narayana Reddy, who had just been released from jail, was the candidate with the highest margin in any constituency in India, greater than that of Jawaharlal Nehru, which became a major source of embarrassment for the Congress.[84] The Communist Party was still banned in the state and had contested through a registered, unrecognised organisation called the People's Democratic Front with no official symbol or much campaigning; the ban was lifted after the election.[83] In 1956, the long-standing demand of the Andhra communists for Visalandhra was fulfilled through the States Reorganisation Act. Hyderabad State was dissolved, and the region of Telangana merged with Andhra State to form Andhra Pradesh. Under pressure from the party, the Congress government separated Andhra State from Madras State in 1953.[85]

Communes and guerrilla squads

Structure and organisation

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

|

The communist peasant rebellion set up a system of governance called gram rajyams or village communes which managed all administrative and judicial functions.[49][86] They consisted of samitis (committees) elected in village meetings with universal adult franchise.[28][87] The number of members in each samiti ranged from five to seven and varied between villages.[30] The samitis supervised the redistribution of land and organised systems for dispute resolution, and to address complaints, conflicts and abuses including family and personal issues.[87] The former role of the deshmukhs was replaced by these systems.[28] The communes in the later stage established judicial courts with a jury system.[51] The individual communes lacked coordination with each other and suffered from isolation through the entire duration of the rebellion.[88]

The Andhra Mahasabha and Communist Party of India were undifferentiated by the villagers and collectively were simply known as Sangham (The Organisation), from their reference to the initial village level organisations called sanghams.[42] The porosity in membership of the Sangham was very high, anyone who supported and participated was de facto considered a member of the party which in turn made entire villages an extension of the party itself. Any villager could be elected to positions within it.[89]

The dalams (squads) were initially created for defensive purposes.[28][87] They developed into an armed force and were reorganised separately from the organisation of the communes. The garrison village squads remained within them while guerrilla squads were divided into five area groups, each with a number of zones and a commanding officer in each zone overseeing several squads.[30] The individual squads were composed of 10 combatants.[30] The revolutionary headquarters became the coordination centre for the squads.[41] The squad leaders in the early stages were usually middle peasantry with small landholding while the majority of the members were landless labourers and rural poor. The disparity existed as a consequence of much of the population being illiterate, and literacy became a requirement for effective long-distance communication. Only 10% of the population in Telangana was literate and the ones that could be found were from the middle peasantry.[42]

Social revolution

The new system of governance marked a radical shift from a feudal autocracy to a network of decentralised village democracies,[74] causing a social revolution in the duration of the rebellion.[86] The entire feudal hierarchy intertwined with theological and caste-based justifications broke down in favour of a vision of an egalitarian new order. Chakali Ilamma later recalled, "I was so proud of the Sangham. They said that the poor would be equal and their time would come ... How can the dream of a new order that they spoke of ever leave us?" Ilamma was part of one of the first instances of resistance to durra coercion during the agitations of 1944–46.[90]

The village samitis instituted crash course education schemes, literacy programs, prohibited forced marriages, and legalised and introduced programs to destigmatise divorces and widow remarriages. Caste distinctions broke down during the rebellion as the villagers and especially the squad members were necessitated into working together. One of the most significant impacts of the rebellion was a change in the relations between sexes. The workforce participation of women increased substantially and prevalent domestic gender norms were questioned. In the early stages, women had begun serving in auxiliary roles for the squads. They eventually began to be recruited in the squads themselves despite the abundance of male and female volunteers. Discriminatory attitudes persisted to an extent with a harsher reception to mistakes made by women. Beliefs in gods, demons and superstitions also declined in the population during this period.[46]

The early onset of the land seizures marked the beginning of the land redistribution process.[28] The task of managing land distribution was taken over by the samitis;[87] land revenues were abolished.[91] The communes also introduced regulations on interest rates, guarantees on repayments and price control measures.[92] The period was marked by exhilaration among the peasantry. The rebels no longer had to pay exorbitant rents, taxes or repay debts. They had gained land through redistribution instead, and were able to feed themselves two meals a day for the first time in their lives.[90]

The lands of jagirdars and deshmukhs were the primary targets for redistribution, but government owned wastelands and forest lands also came under the redistribution scheme.[92] Lands acquired by durras through coercion and lands worked by evicted tenants were readily granted to the evicted cultivators.[91] The ceiling of land ownership was progressively reduced over time and ceiling surplus lands were redistributed. Initially set at 500 acres, it was reduced to 200 acres and eventually after pressure from the majority of the peasantry was reduced to 100 dry acres and 10 wet acres. Over one million acres of land were redistributed by 1948.[92][93]

Contrary to expectations, the land redistribution program resulted in an expansion of agricultural production in spite of the ongoing conflict with the state. The grains produced were hidden in scattered storage deposits in the fields. The communes were still dependent on the external market to sell the produce and had to bribe middlemen to market goods from the rebel villages.[92]

Medical support

The medical facilities of the rebels in Telangana were poor, and preventative measures were emphasised. The city of Bezawada (Vijayawada) served as the primary source of medical support for the rebellion. Doctors sympathetic to the rebellion arranged a special ward in the Vijayawada General Hospital to treat injured combatants. They also supplied the rebellion with first aid kits and anti-venom against snake bites. Two doctors from the city joined the rebels to provide paramedic training to squad members. The paramedics trained in ad hoc facilities by the doctors, were able to contain a cholera outbreak in villages near Bhongir during the rebellion by emphasising on disinfection of drinking water with the use of coal and lime.[46]

Legacy

No official account of the attempted suppression of the rebellion, was released to the public even 70 years later.[63] Meanwhile, the divisions that emerged within the rebel camp persisted and led to the 1964 split in the Communist Party of India.[94] There was a renewed interest in the rebellion among academics and activists in the 1970s and 80s.[95][96] The rebellion has since become a source of legends and inspiration among Telangana's population as well as the radical and progressive left across India.[95] Krishan Chander's Hindi/Urdu novella Jab Khet Jage was based on the Telangana Rebellion.[97] "Palletoori Pillagada", a song describing the rebellion was written by Suddala Hanmanthu and retained its popularity years afterwards particularly among the tribal population where it was incorporated into folk adaptations.[98] The Telugu film Maa Bhoomi (1980) was set in the rebellion and became a significant commercial success.[99] The cinematographer Rajendra Prasad made his first feature film Nirantharam (1995), in Telugu, starring Raghuvir Yadav and Chinmayee Surve on the subject.[100]

References

Notes

- Agrarian reforms of Salar Jung I had established "direct contact" with occupants, passing the responsibility of land revenue payments from the revenue collectors to the occupants, the deshmukhs and deshpandes previously acted as revenue farmers.[6]

- The first communist connection likely established between Veerlapadu village (Nandigama taluq) in Krishna district and Allinagaram village (Madhira taluq) in Warangal district.[15]

- The first communist units were formed in 1940 after Devulapalli Venkateswara Rao, Pervaelli Venkataramanaiah, Sarvadevabhatla Ramanadham, Chirravuri Lakshminarasaiah established contact with Chandra Rajeswara Rao.[15]

- Naya Abad developed around the newspapers Rayyat edited by Mandumulu Narsing Rao and Payyam edited by Khaji Abdul Gafoor.[15]

- The Muslim supremacist organisation of Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen and reactionary Hindu nationalist organisations like the Hindu Mahasabha and the Arya Samaj were influential in the city of Hyderabad.[14]

- The left-wing faction within the AMS was led by Ravi Narayan Reddy, Baddam Yella Reddy and Arutla Ramachandra Reddy.[15]

- The agitations of 1944–1946 were located primarily in Nalgonda district on the estates of jagirdars and deshmukhs of the largest landholdings.[25]

- 550 estates with over 500 acres of land owned 60 to 70% of the total cultivatable land in Nalgonda, Warangal and Mahbubnagar districts.[11]

- Vishnur Deshmukh had an estate of 40,000 acres covering over 40 villages.[11]

- The initial militant actions of 1946 were sometimes carried out without approval from sangham leaders.[25]

- The socialists of Maharashtra Parishad led agitation around 1944, similar to that of the Telangana communists, gaining a mass following in Marathawada.[31]

- The leader of the Marathawada socialists, Swami Ramananda Tirtha became embroidered in a controversy when their internal correspondences with Mahatma Gandhi on the communist question were released verbatim by the Communist Party. Tirtha was widely assumed to have leaked it himself.[32]

- K.R. Vaidya, a moderate veteran was insulted that the younger committee had not accepted his recommendations and distributed a letter condemning Govind Das Shroff and the Marathawada leftists for being overtly sympathetic to the communists.[32]

- Following Tirtha's arrest, a new line of leadership was established by the Hyderabad State Congress leftists in Bombay led by Govind Das Shroff, Gopaliah Subbukrishna Melkote and Digambarrao Govindrao Bindu.[39]

Citations

- Leonard 2003, pp. 365–367.

- Elliott 1974, p. 28.

- Elliott 1974, p. 32.

- Dhanagare 1983, p. 183.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 180–184.

- Gupta 1984a, p. 4.

- Gupta 1984a, pp. 4–5.

- Gupta 1984a, p. 5.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 184–186.

- Shankar 2016, p. 488.

- Sundarayya 1973a, pp. 8–13.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 186–189.

- Chatterjee 2005, pp. 137–154.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 189–193.

- Thirumali 1996, pp. 164–168.

- Thirumali 1996, pp. 168–174.

- Benichou 2000, pp. 164–165.

- Benichou 2000, pp. 128–131.

- Benichou 2000, pp. 164–166.

- Thirumali 1996, pp. 174–177.

- Benichou 2000, pp. 147–153.

- Roosa 2001, p. 63.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 66–68.

- Ram 1973, p. 1026.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 193–194.

- Dhanagare 1974, pp. 120–121.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 194–195.

- Gupta 1984a, p. 14.

- Elliott 1974, pp. 43–45.

- Gupta 1984a, p. 15.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 61–66.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 68–73.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 195–196.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 73–75.

- Pavier 1981, pp. 111–112.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 196–197.

- Elliott 1974, p. 42.

- Elliott 1974, pp. 41–43.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 75–76.

- Ralhan 1997, p. 82.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 197–198.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 76–77.

- Pavier 1981, pp. 115–116.

- Dhanagare 1983, p. 197.

- Gupta 1984a, pp. 15–16.

- Gupta 1984a, p. 16.

- Dhanagare 1983, p. 182.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 197–199.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 198–199.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 79–80.

- Guha 1976, p. 41.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 199–200.

- Roosa 2001, p. 80.

- Dhanagare 1983, p. 200.

- Gupta 1984a, p. 18.

- Dhanagare 1983, p. 199.

- Gupta 1984a, p. 19.

- Barua 2003, pp. 51–52.

- Gerlach & Six 2020, p. 131.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 82–83.

- Gupta 1984a, pp. 19–20.

- Roosa 2001, p. 81.

- Gerlach & Six 2020, p. 132.

- Gray 2015, p. 403.

- Guha 1976, pp. 41–42.

- Gerlach & Six 2020, p. 133.

- Dhanagare 1983, p. 203.

- Gupta 1984a, pp. 18–21.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 81–82.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 203–204.

- Roosa 2001, p. 82.

- Gupta 1984a, p. 20.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 202–204.

- Elliott 1974, p. 45.

- Roosa 2001, p. 83.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 200–201.

- Gupta 1984a, p. 22.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 84–86.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 85–86.

- Gupta 1984a, pp. 21–22.

- Gupta 1984a, p. 21.

- Ram 1973, pp. 1029–1030.

- Ram 1973, p. 1030.

- Banerjee 2006, p. 3840.

- Mantena 2014, pp. 350–355.

- Gupta 1984b, p. 22.

- Dhanagare 1974, pp. 123–124.

- Dhanagare 1983, pp. 205–206.

- Roosa 2001, pp. 77–78.

- Roosa 2001, p. 77.

- Dhanagare 1983, p. 198.

- Gupta 1984a, p. 17.

- Dhanagare 1974, p. 117.

- Ram 1973, pp. 1031–1032.

- Dhanagare 1983, p. 207.

- Elliott 1974, p. 46.

- Ravikumar, Aruna (14 September 2019). "The Yoke of Oppression". The Hans India. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- Dhanaraju, Vulli (2015). "Voice of the Subaltern Poet: Contribution of Suddala Hanumanthu in Telangana Peoples' Movement". Research Journal of Language, Literature and Humanities. 2 (7): 6–7. ISSN 2348-6252. S2CID 59468865.

- Krishnamoorthy, Suresh (24 March 2015). "Maa Bhoomi will forever be alive in people's minds". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- Dundoo, Sangeetha Devi (15 June 2019). "Behind the scenes of 'Mallesham', the Telugu biopic on an ikat weaver". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

Sources

- Banerjee, Sumanta (2006). "Salvaging an Endangered Institution". Economic and Political Weekly. 41 (36): 3837–3841. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4418667. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021 – via JSTOR.

- Barua, Pradeep (2003). Gentlemen of the Raj: The Indian Army Officer Corps, 1817-1949. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-97999-7.

- Benichou, Lucien D. (2000). From Autocracy to Integration: Political Developments in Hyderabad State, 1938-1948. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-1847-6.

- Chatterjee, Indrani (2005). "Abolition by denial: the South Asian example". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Abolition and Its Aftermath in the Indian Ocean Africa and Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-77078-5.

- Dhanagare, D. N. (1974). "Social origins of the peasant insurrection in Telangana (1946-51)". Contributions to Indian Sociology. SAGE Publications. 8 (1): 109–134. doi:10.1177/006996677400800107. ISSN 0069-9667. S2CID 143442292.

- Dhanagare, D. N. (1983). Peasant Movements in India 1920-1950. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-562903-3.

- Elliott, Carolyn M. (1974). "Decline of a Patrimonial Regime: The Telengana Rebellion in India, 1946-51". The Journal of Asian Studies. 34 (1): 27–47. doi:10.2307/2052408. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2052408. S2CID 59483193. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021 – via JSTOR.

- Gerlach, Christian; Six, Clemens (2020). The Palgrave Handbook of Anti-Communist Persecutions. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-54963-3.

- Guha, Ranajit (1976). "Indian democracy: Long dead, now buried". Journal of Contemporary Asia. Taylor & Francis. 6 (1): 39–53. doi:10.1080/00472337685390051. ISSN 0047-2336. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- Gupta, Akhil (August 1984b). "Revolution in Telengana (1946–1951): (Part Two)". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Duke University Press. 4 (2): 22–32. doi:10.1215/07323867-4-2-22. ISSN 1089-201X. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- Gupta, Akhil (May 1984a). "Revolution in Telengana 1946–1951 (Part One)". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Duke University Press. 4 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1215/07323867-4-1-1. ISSN 1089-201X. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- Gray, Hugh (2015). "Andhra Pradesh". In Myron, Wiener (ed.). State Politics in India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7914-4.

- Leonard, Karen (2003). "Reassessing Indirect Rule in Hyderabad: Rule, Ruler, or Sons-in-Law of the State?". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 37 (2): 363–379. doi:10.1017/S0026749X0300204X. ISSN 1469-8099. S2CID 143511635. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- Mantena, Rama Sundari (2014). "The Andhra Movement, Hyderabad State, and the Historical Origins of the Telangana Demand: Public Life and Political Aspirations in India, 1900–56". India Review. Taylor & Francis. 13 (4): 337–357. doi:10.1080/14736489.2014.964629. ISSN 1473-6489. S2CID 154482789.

- Pavier, Barry (1981). The Telengana Movement, 1944-51. Vikas Publishing House. ISBN 978-0-7069-1289-0.

- Ralhan, O. P., ed. (1997). Encyclopedia of Political Parties: Socialist Movement in India. Vol. 24. Anmol Publication. ISBN 9788174882875.

- Ram, Mohan (1973). "The Telengana Peasant Armed Struggle, 1946-51". Economic and Political Weekly. 8 (23): 1025–1032. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4362720. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021 – via JSTOR.

- Roosa, John (2001). "Passive revolution meets peasant revolution: Indian nationalism and the Telangana revolt". The Journal of Peasant Studies. Taylor & Francis. 28 (4): 57–94. doi:10.1080/03066150108438783. ISSN 0306-6150. S2CID 144106512. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- Shankar, Amaragani Hari (2016). "Commercialization of Agriculture and Socio-political ramifications in Telangana districts of Hyderabad State: 1925 – 1956". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 77: 485–495. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 26552674. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021 – via JSTOR.

- Sundarayya, P. (1973a). "Telangana People's Armed Struggle, 1946-1951. Part One: Historical Setting". Social Scientist. 1 (7): 3–19. doi:10.2307/3516269. ISSN 0970-0293. JSTOR 3516269. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021 – via JSTOR.

- Thirumali, I. (1996). "The Political Pragmatism of the Communists in Telangana, 1938-48". Social Scientist. 24 (4/6): 164–183. doi:10.2307/3517795. ISSN 0970-0293. JSTOR 3517795. Archived from the original on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021 – via JSTOR.

Further reading

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2.

- Balagopal, K. (1983). "Telangana Movement Revisited". Economic and Political Weekly. 18 (18): 709–712. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4372111 – via JSTOR.

- Benbabaali, Dalel (2016). "From the peasant armed struggle to the Telangana State: changes and continuities in a South Indian region's uprisings". Contemporary South Asia. Taylor & Francis. 24 (2): 184–196. doi:10.1080/09584935.2016.1195340. ISSN 0958-4935. S2CID 152251545.

- Motta, S.; Nilsen, A. Gunvald, eds. (2011). Social Movements in the Global South: Dispossession, Development and Resistance. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-230-30204-4.

- Omvedt, Gail (1980). "Caste, Agrarian Relations and Agrarian Conflicts". Sociological Bulletin. 29 (2): 142–170. doi:10.1177/0038022919800202. ISSN 0038-0229. S2CID 157995064 – via SAGE Journals.

- Purushotham, Sunil (2021). From Raj to Republic: Sovereignty, Violence, and Democracy in India. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-1455-0.

- Sundarayya, P. (1973b). "Telangana People's Armed Struggle, 1946-1951. Part Two: First Phase and Its Lessons". Social Scientist. 1 (8): 18–42. doi:10.2307/3516214. ISSN 0970-0293. JSTOR 3516214 – via JSTOR.

- Sundarayya, P. (1973c). "Telangana People's Armed Struggle, 1946-51. Part Three: Pitted against the Indian Army". Social Scientist. 1 (9): 23–46. doi:10.2307/3516496. ISSN 0970-0293. JSTOR 3516496 – via JSTOR.

- Sundarayya, P. (1973d). "Telangana People's Armed Struggle, 1946-51: Part Four: Background to a Momentous Decision". Social Scientist. 1 (10): 22–52. doi:10.2307/3516280. ISSN 0970-0293. JSTOR 3516280 – via JSTOR.

- Welch, Claude Emerson (1980). Anatomy of Rebellion. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-441-9.