Sauron

Sauron (pronounced /ˈsaʊrɒn/[T 2]) is the title character[lower-alpha 1] and the primary antagonist,[1] through the forging of the One Ring, of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, where he rules the land of Mordor and has the ambition of ruling the whole of Middle-earth. In the same work, he is identified as the "Necromancer" of Tolkien's earlier novel The Hobbit. The Silmarillion describes him as the chief lieutenant of the first Dark Lord, Morgoth. Tolkien noted that the Ainur, the "angelic" powers of his constructed myth, "were capable of many degrees of error and failing", but by far the worst was "the absolute Satanic rebellion and evil of Morgoth and his satellite Sauron".[T 4] Sauron appears most often as "the Eye", as if disembodied.

| Sauron | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien character | |

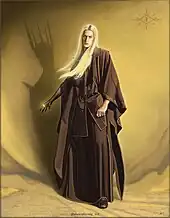

J. R. R. Tolkien's watercolour illustration of Sauron[T 1] | |

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases |

|

| Race | Maia |

| Book(s) | |

Tolkien, while denying that absolute evil could exist, stated that Sauron came as near to a wholly evil will as was possible. Commentators have compared Sauron to the title character of Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula, and to Balor of the Evil Eye in Irish mythology. Sauron is briefly seen in a humanoid form in Peter Jackson's film trilogy, which otherwise shows him as a disembodied, flaming Eye.

Fictional history

Before the world's creation

The Ainulindalë, the cosmological myth prefixed to The Silmarillion, explains how the supreme being Eru initiated his creation by bringing into being innumerable good,[T 3] immortal, angelic spirits, the Ainur, including Sauron, one of the lesser Ainur, the Maiar.[T 4][T 5] In his origin, Sauron therefore perceived the Creator directly.[T 6] He was of a "far higher order" than the Maiar who later came to Middle-earth as the Wizards, such as Gandalf and Saruman.[T 5] The Vala Melkor (later called Morgoth) rebelled against Eru, breaking the cosmic music that Eru had used in the world's creation with discord.[T 7][T 8] So began "the evils of the world",[T 9] which Sauron continued.[T 6]

Servant of Aulë

Sauron served Aulë, the smith of the Valar, acquiring much knowledge;[T 10][T 11] he was at first called Mairon ("The Admirable", in Tolkien's invented language of Quenya) until he joined Melkor. In Beleriand, he was called Gorthu "Mist of Fear" and Gorthaur "The Cruel" in Sindarin, another of Tolkien's invented languages.[T 12] Sauron was drawn to the power of Melkor,[T 13] who attracted him by seeming to have power to "effect his designs quickly and masterfully", as Sauron hated disorder.[T 6] Sauron became a spy for Melkor on the isle of Almaren, the dwelling-place of the Valar.[T 10] Melkor soon destroyed Almaren, and the Valar moved to the Blessed Realm of Valinor, still not perceiving Sauron's treachery.[T 14] Sauron left the Blessed Realm and went to Middle-earth, the central continent of Arda, where Melkor had established his stronghold.[T 15] Sauron openly joined the Valar's enemy.[T 5]

Lieutenant of Morgoth

Sauron became Morgoth's capable servant,[T 16] helping him in all the "deceits of his cunning".[T 11] By the time Elves awoke in the world, Sauron had become Melkor's lieutenant and was given command over the new stronghold of Angband. The Valar made war on Melkor and captured him, but Sauron escaped.[T 17] He hid in Middle-earth, repaired Angband, and began breeding Orcs. Melkor escaped back to Middle-earth with the Silmarils.[T 16] This conflicts with earlier versions of the story, in which Orcs existed before the wakening of the Elves, as in The Fall of Gondolin, p. 25. Sauron directed the war against the Elves, conquering the Elvish fortress of Minas Tirith (not to be confused with the later city in Gondor of the same name) on the isle of Tol Sirion in Beleriand. Lúthien and Huan the Wolfhound came to this fallen stronghold to save the imprisoned Beren, Lúthien's lover. Sauron, transformed into a werewolf, battled Huan, who took him by the throat; he was defeated and left as a huge vampire bat. Lúthien destroyed the tower and rescued Beren from the dungeons. Eärendil sailed to the Blessed Realm, and the Valar moved against Morgoth in the War of Wrath; he was defeated and cast into the Outer Void beyond the world, but again Sauron escaped.[T 18]

The Rings of Power in the Second Age

About 500 years into the Second Age, Sauron reappeared,[T 16] intent on taking over Middle-earth and ruling it as a God-King.[T 5][T 14][T 19][T 6] To seduce the Elves into his service, Sauron assumed a fair appearance as Annatar, "Lord of Gifts",[T 13] befriended the Elven-smiths of Eregion, led by Celebrimbor, and counselled them in arts and magic. With Sauron's assistance, the Elven-smiths forged the Rings of Power. Sauron then secretly forged the One Ring, to rule all other rings, in the volcanic Mount Doom in Mordor.[T 14] The Elves detected his influence when he put on the One Ring, and removed their Rings. Enraged, Sauron initiated a great war and conquered much of the land west of Anduin. Sauron overran Eregion, killed Celebrimbor, and seized the Seven and the Nine Rings of Power. The Three Rings were saved by the Elves, specifically Gil-galad, Círdan, and Galadriel. Sauron besieged Imladris, battled Khazad-dûm and Lothlórien, and pushed further into Gil-galad's realm. The Elves were saved when a powerful army from Númenor arrived to their aid, defeating Sauron's forces and driving the remnant back to Mordor. Sauron fortified Mordor and completed the Dark Tower of Barad-dûr. He distributed the remaining rings of the Seven and the Nine to lords of Dwarves and Men, respectively. Dwarves proved too resilient to bend to his will, but he enslaved Men as the Nazgûl, his most feared servants. Orcs and Trolls became his servants, along with Easterlings and men of Harad.[T 5]

Downfall of Númenor

Toward the end of the Second Age, Ar-Pharazôn, king of Númenor, led a massive army to Middle-earth. Sauron surrendered, to corrupt Númenor from within.[T 20][T 4] With the One Ring, Sauron soon dominated the Númenóreans.[T 20] He used his influence to undermine the religion of Númenor, acting as the high priest of Melkor and making people worship Melkor with human sacrifice.[T 4][T 6] Sauron convinced Ar-Pharazôn to attack Aman by sea to steal immortality from the Valar.[T 4][T 14] The Valar laid down their guardianship of the world and appealed to Eru.[T 4] Eru destroyed the fleet, reshaped the world into a globe, removing Aman from the physical world. Númenor was drowned under the sea, Sauron's body was destroyed in the tumults and he lost the ability to appear beautiful.[T 20]

War of the Last Alliance

Led by Elendil, nine ships carrying faithful Númenóreans were saved from the Downfall; they founded the kingdoms of Gondor and Arnor in Middle-earth. Sauron returned to Mordor; Mount Doom again erupted.[T 21] Sauron captured Minas Ithil and destroyed the White Tree; Elendil's son Isildur escaped down the Anduin. Anárion defended Osgiliath and for a time drove Sauron's forces back to the mountains.[T 13] Isildur and Anárion formed an alliance and defeated Sauron at Dagorlad. They invaded Mordor and laid siege to Barad-dûr for seven years. Finally Sauron came out to fight Elendil and Gil-galad face to face.[T 14] When Elendil fell, his sword Narsil broke beneath him. Isildur took up the hilt-shard of Narsil and cut the One Ring from Sauron's hand, vanquishing Sauron. Elrond and Círdan, Gil-galad's lieutenants, urged Isildur to destroy the Ring by casting it into Mount Doom, which would have banished Sauron from Middle-earth for ever, but he refused and kept it for his own.[T 13]

Third Age

A few years after the War of the Last Alliance, Isildur's army was ambushed by Orcs at the Gladden Fields. Isildur put on the Ring and attempted to escape by swimming across Anduin, but the Ring, trying to return to Sauron, slipped from his finger. Isildur was killed by Orc archers. Sauron spent a thousand years as a shapeless, dormant evil.[T 22]

The Necromancer of Dol Guldur

Sauron concealed himself in the south of Mirkwood as the Necromancer, in the stronghold of Dol Guldur, "Hill of Sorcery".[T 23] The Valar sent five Maiar as Wizards to oppose the darkness, believing the Necromancer to be a Nazgûl rather than Sauron himself. The chief of the Nazgûl, the Witch-king of Angmar, repeatedly attacked the northern realm of Arnor, destroying it. When attacked by Gondor, the Witch-king retreated to Mordor, gathering the Nazgûl there.[T 13] The Nazgûl captured Minas Ithil, which was renamed Minas Morgul, and seized its palantír, one of the seven seeing stones brought from Númenor.[T 24] The White Council of Wizards discovered Sauron in Dol Guldur,[T 25] and drove him from Mirkwood; he returned to Mordor, openly declared himself, rebuilt Barad-dûr, and bred armies of specially large Orcs - the Uruks.[T 26]

The War of the Ring

In 3017, Gandalf identified Bilbo's Ring, now passed down to Bilbo's cousin Frodo, as Sauron's One Ring. He tasked Frodo and his friend Sam Gamgee with taking the Ring to Rivendell.[T 27] Soon afterward, however, Gandalf discovered Saruman's treachery. Sauron sent the Nazgûl to the Shire; they pursued Frodo, who escaped to Rivendell. There, Elrond convened a council. It determined that the Ring should be destroyed in Mount Doom, and formed the Fellowship of the Ring to achieve this. Saruman attempted to capture the Ring, but his army was destroyed and his stronghold at Isengard was overthrown. The palantír of Orthanc fell into the hands of the Fellowship; Aragorn, Isildur's descendant and heir to the throne of Gondor, used it to show himself to Sauron as if he held the Ring. Sauron, troubled by this revelation, attacked Minas Tirith sooner than he had planned. His army was destroyed at the Battle of the Pelennor Fields. Meanwhile, Frodo and Sam entered Mordor through the pass of Cirith Ungol. Aragorn diverted Sauron's attention with an attack on the Black Gate of Mordor.[T 28] Frodo and Sam reached Mount Doom, but at the last minute Frodo was entranced by the Ring and claimed it for himself. Gollum then seized the Ring and fell into the Cracks of Doom, destroying the Ring and himself. Thus Sauron was utterly defeated, and vanished from Middle-earth.[T 28] Tolkien describes Sauron's destruction:

...black against the pall of cloud, there rose a huge shape of shadow, impenetrable, lightning-crowned, filling all the sky. Enormous it reared above the world, and stretched out towards them a vast threatening hand, terrible but impotent: for even as it leaned over them, a great wind took it, and it was all blown away, and passed; and then a hush fell.[T 29]

Appearance

Physical body

Tolkien never described Sauron's appearance in detail, though he painted a watercolour illustration of him.[T 1] Sarah Crown, in The Guardian, wrote that "we're never ushered into his presence; we don't hear him speak. All we see is his influence".[2] She called it "a bold move, to leave the book's central evil so undefined – an edgeless darkness given shape only through the actions of its subordinates",[2] with the result that he becomes "truly unforgettable ... vaster, bolder and more terrifying through his absence than he could ever have been through his presence".[2]

He was initially able to change his appearance at will, but when he became Morgoth's servant, he took a sinister shape. In the First Age, the outlaw Gorlim was ensnared and brought into "the dreadful presence of Sauron", who had daunting eyes.[T 30] In the battle with Huan, the hound of Valinor, Sauron took the form of a werewolf. Then he assumed a serpent-like form, and finally changed back "from monster to his own accustomed [human-like] form".[T 31] He took on a beautiful appearance at the end of the First Age to charm Eönwë, near the beginning of the Second Age when appearing as Annatar to the Elves, and again near the end of the Second Age to corrupt the men of Númenor. He appeared then "as a man, or one in man's shape, but greater than any even of the race of Númenor in stature ... And it seemed to men that Sauron was great, though they feared the light of his eyes. To many he appeared fair, to others terrible; but to some evil."[T 32] After the destruction of his fair form in the fall of Númenor, Sauron always took the shape of a terrible dark lord.[T 33] His first incarnation after the Downfall of Númenor was hideous, "an image of malice and hatred made visible".[T 34] Isildur recorded that Sauron's hand "was black, and yet burned like fire".[T 3]

Eye of Sauron

Throughout The Lord of the Rings, "the Eye" (known by other names, including the Red Eye, the Evil Eye, the Lidless Eye, the Great Eye) is the image most often associated with Sauron. Sauron's Orcs bore the symbol of the Eye on their helmets and shields, and referred to him as the "Eye" because he did not allow his name to be written or spoken, according to Aragorn.[T 35][lower-alpha 2] The Lord of the Nazgûl threatened Éowyn with torture before the "Lidless Eye" at the Battle of the Pelennor Fields.[T 36] Frodo had a vision of the Eye in the Mirror of Galadriel:[T 37]

The Eye was rimmed with fire, but was itself glazed, yellow as a cat's, watchful and intent, and the black slit of its pupil opened on a pit, a window into nothing.[T 37]

Later, Tolkien writes as if Frodo and Sam really glimpse the Eye directly. The mists surrounding Barad-dûr are briefly withdrawn, and:

one moment only it stared out ... as from some great window immeasurably high there stabbed northward a flame of red, the flicker of a piercing Eye ... The Eye was not turned on them, it was gazing north ... but Frodo at that dreadful glimpse fell as one stricken mortally.[T 38]

This raises the question of whether an "Eye" was Sauron's actual manifestation, or whether he had a body beyond the Eye.[T 39] Gollum (who was tortured by Sauron in person) tells Frodo that Sauron has, at least, a "Black Hand" with four fingers.[T 40] The missing finger was cut off when Isildur took the Ring, and the finger was still missing when Sauron reappeared centuries later. Tolkien writes in The Silmarillion that "the Eye of Sauron the Terrible few could endure" even before his body was lost in the War of the Last Alliance.[T 34] In the draft text of the climactic moments of The Lord of the Rings, "the Eye" stands for Sauron's very person, with emotions and thoughts:[T 39]

The Dark Lord was suddenly aware of him [Frodo], the Eye piercing all shadows ... Its wrath blazed like a sudden flame and its fear was like a great black smoke, for it knew its deadly peril, the thread upon which hung its doom ... [I]ts thought was now bent with all its overwhelming force upon the Mountain..."[T 39]

Christopher Tolkien comments: "The passage is notable in showing the degree to which my father had come to identify the Eye of Barad-dûr with the mind and will of Sauron, so that he could speak of 'its wrath, its fear, its thought'. In the second text ... he shifted from 'its' to 'his' as he wrote out the passage anew."[T 39]

Concept and creation

Since the earliest versions of The Silmarillion legendarium as detailed in the History of Middle-earth series, Sauron underwent many changes. The prototype or precursor Sauron-figure was a giant monstrous cat, the Prince of Cats. Called Tevildo, Tifil and Tiberth among other names, this character played the role later taken by Sauron in the earliest version of the story of Beren and Tinúviel in The Book of Lost Tales in 1917.[T 41] The Prince of Cats was later replaced by Thû, the Necromancer. The name was then changed to Gorthû, Sûr, and finally to Sauron. Gorthû, in the form Gorthaur, remained in The Silmarillion;[T 11] both Thû and Sauron name the character in the 1925 Lay of Leithian.[T 42]

The story of Beren and Lúthien also features the heroic hound Huan and involved the subtext of cats versus dogs in its earliest form. Later the cats were changed to wolves or werewolves, with the Sauron-figure becoming the Lord of Werewolves.[T 43]

Before the publication in 1977 of The Silmarillion, Sauron's origins and true identity were unclear to those without access to Tolkien's notes. In 1968, the poet W. H. Auden conjectured that Sauron might have been one of the Valar.[3]

Interpretations

Wholly evil will

Tolkien stated in his Letters that although he did not think "Absolute Evil" could exist as it would be "Zero", "in my story Sauron represents as near an approach to the wholly evil will as is possible." He explained that, like "all tyrants", Sauron had started out with good intentions but was corrupted by power, and that he "went further than human tyrants in pride and the lust for domination", being in origin an immortal (angelic) spirit. He began as Morgoth's servant; became his representative, in his absence in the Second Age; and at the end of the Third Age actually claimed to be 'Morgoth returned'".[T 44]

Classically reptilian

The classicist J. K. Newman comments that "Sauron's Greek name" makes him "the Lizard", from Ancient Greek σαῦρος (sauros) 'lizard or reptile', and that in turn places Frodo (whose quest destroys Sauron) as "a version of Praxiteles' Apollo Sauroktonos", Apollo the Lizard-killer.[4]

Destructive Dracula-figure

Gwenyth Hood, writing in Mythlore, compares Sauron to Count Dracula from Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula. In her view, both of these monstrous antagonists seek to destroy, are linked to powers of darkness, are parasitical on created life, and are undead. Both control others psychologically and have "hypnotic eyes". Control by either of them represents "high spiritual terror" as it is a sort of "damnation-on-earth".[5]

Celtic Balor of the Evil Eye

Edward Lense, also writing in Mythlore, identifies a figure from Celtic mythology, Balor of the Evil Eye, as a possible source for the Eye of Sauron. Balor's evil eye, in the middle of his forehead, was able to overcome a whole army. He was king of the evil Fomoire, who like Sauron were evil spirits in hideously ugly bodies. Lense further compares Mordor to "a Celtic hell", just as the Undying Lands of Aman resemble the Celtic Earthly Paradise of Tír na nÓg in the furthest (Atlantic) West; and Balor "ruled the dead from a tower of glass".[6]

Antagonist

The Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger writes that if there was an opposite to Sauron in The Lord of the Rings, it would not be Aragorn, his political opponent, nor Gandalf, his spiritual enemy, but Tom Bombadil, the earthly Master who is entirely free of the desire to dominate and hence cannot be dominated.[7]

| Sauron | Tom Bombadil | |

|---|---|---|

| Role | Antagonist | Earthly counterpart |

| Title | Dark Lord | "Master" |

| Purpose | Domination of whole of Middle-earth | Care for The Old Forest "No hidden agenda, no covert desire or plan of operation" |

| Effect of the One Ring | "Power over other wills" | No effect on him "as he is not human", nor does it make others invisible to him, or him to others |

| How he sees the Ring | The Eye of Sauron desires to dominate through the Ring | Looks right through it, his "blue eye peering through the circle of the Ring" |

Adaptations

Film

In film versions of The Lord of the Rings, Sauron has been left off-screen as "an invisible and unvisualizable antagonist"[9] as in Ralph Bakshi's 1978 animated version,[9] or as a disembodied Eye, as in Rankin/Bass' 1980 animated adaptation of The Return of the King.[10]

In the 2001–2003 film trilogy directed by Peter Jackson, Sauron is voiced by Alan Howard. He is briefly shown as a large humanoid figure clad in spiky black armour, portrayed by Sala Baker,[11][8] but appears only as the disembodied Eye throughout the rest of the storyline.[12] In earlier versions of Jackson's script, Sauron does battle with Aragorn, as shown in the extended DVD version of The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. The scene was removed as too large a departure from Tolkien's text and was replaced with Aragorn fighting a troll.[13] Sauron appears as the Necromancer in Jackson's The Hobbit film adaptations, where he is voiced by Benedict Cumberbatch.[14]

Sauron appears in the form of his eye in The Lego Batman Movie voiced by Jemaine Clement. He is one of the many pre-existing villains the Joker frees from the Phantom Zone to run amok in Gotham City.[15][16]

Television

Sauron's rise to power in the Second Age is portrayed in the Amazon Prime prequel series The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.[17] He appears disguised as the non-canonical character Halbrand, played by Charlie Vickers.[18]

Video games

Sauron appears in the merchandise of the Jackson films, including computer and video games. These include The Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle-earth II (where he was voiced by Fred Tatasciore), The Lord of the Rings: Tactics, and The Lord of the Rings: The Third Age.[19][20] In the Lord of the Rings Online game, he is featured as an enemy.[21]

In culture

The Eye of Sauron is mentioned in The Stand, a post-apocalyptic novel written by Stephen King. The villain Randall Flagg possesses an astral body in the form of an "Eye" akin to the Lidless Eye. The novel itself was conceived by King as a "fantasy epic like The Lord of the Rings, only with an American setting".[22] The idea of Sauron as a sleepless eye that watches and seeks the protagonists also influenced King's epic fantasy series The Dark Tower; its villain, the Crimson King, is a similarly disembodied evil presence whose icon is also an eye.[23]

In the Marvel Comics Universe, the supervillain Sauron, an enemy of the X-Men, names himself after the Tolkien character.[24] In the comic series Fables, by Bill Willingham, one character is called "The Adversary", an ambiguous figure of immense evil and power believed to be responsible for much of the misfortune in the Fables' overall history. Willingham has stated "The Adversary", in name and in character, was inspired by Sauron.[25]

Notes

- This is made clear in the chapter "The Council of Elrond", where Glorfindel states that "soon or late the Lord of the Rings would learn of its hiding place and would bend all his power towards it".[T 3]

- A notable exception was Sauron's emissary, the Mouth of Sauron.

References

Primary

- Hammond & Scull 1995, pp. 152ff

- Tolkien 1977, "Note on Pronunciation": "The first syllable of Sauron is like English sour, not sore"

- Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 2 "The Council of Elrond"

- Carpenter 1981, #156 to Robert Murray, S.J., 4 November 1954

- Carpenter 1981, #183, notes on W. H. Auden's review of The Return of the King

- Tolkien 1993, pp. 395–398

- The story of the Song of Creation was presented by the Valar "according to our modes of thought and our imagination of the visible world, in symbols that were intelligible to us". Tolkien 1994, p. 407

- Tolkien 1977, "Ainulindalë"

- Tolkien 1996, p. 413

- Tolkien 1993, p. 52

- Tolkien 1977, "Valaquenta"

- Parma Eldalamberon #17, 2007, p. 183

- Tolkien 1977, "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age"

- Carpenter 1981, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

- Tolkien 1955, p. 239

- Tolkien 1993, pp. 420–421

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- Tolkien 1987, p. 333

- Carpenter 1981, #153 to Peter Hastings (draft)

- Carpenter 1981, #211 to Rhona Beare, 14 October 1958

- Tolkien 1955, Appendices

- Tolkien 1980, "The disaster of the Gladden Fields", p. 275

- Tolkien 1955, Appendix B, "The Tale of Years", "The Third Age"

- Tolkien 1980, part 4, ch 3 "The Palantíri"

- Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 2 "The Council of Elrond", and Appendix B.

- Tolkien 1955, Appendix A, "The Stewards": "In the last years of Denethor I the race of Uruks, black orcs of great strength, first appeared out of Mordor." (Denethor I died in TA 2477.)

- Tolkien 1954a, part 1, ch. 2 "The Shadow of the Past"

- Tolkien 1955, book 5, ch. 9 "The Last Debate"

- Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 4 "The Fields of Cormallen"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 19, "Of Beren and Luthien"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 20 "Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad"

- Tolkien 1987, p. 67

- Carpenter 1981, #246 to Eileen Elgar, September 1963

- Tolkien 1977, Akallabêth

- Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 5 "The Departure of Boromir"

- Tolkien 1954, book 5, ch. 6 "The Battle of the Pelennor Fields"

- Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 7 "The Mirror of Galadriel"

- Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 3 "Mount Doom"

- Tolkien 1992, part 1, ch. 4 "Mount Doom"

- Tolkien 1954, book 4, ch. 3 "The Black Gate is Closed"

- Tolkien 1984b, Part Two, "The Tale of Tinúviel"

- Tolkien 1984, "The Lay of Leithian"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 18 "Of the Ruin of Beleriand and the Fall of Fingolfin"

- Carpenter 1981, #183 notes on W. H. Auden's review of The Return of the King

Secondary

- Monroe, Caroline. "How much was Rowling inspired by Tolkien?". GreenBooks, TheOneRing.net. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2006.

- Crown, Sarah (27 October 2014). "Baddies in books: Sauron, literature's ultimate source of evil". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- Auden, W. H. (June 1968). "Good and Evil in The Lord of the Rings". Critical Quarterly. 10 (1–2): 138–142. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8705.1968.tb02218.x.

- Newman, J. K. (2005). "J.R.R. Tolkien's 'The Lord of the Rings': A Classical Perspective". Illinois Classical Studies. 30: 229–247. JSTOR 23065305.

- Hood, Gwenyth (1987). "Sauron and Dracula". Mythlore. 14 (2 (52)): 11–17, 56. Archived from the original on 2020-09-19. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Lense, Edward (1976). "Sauron and Dracula". Mythlore. 4 (1). article 1. Archived from the original on 2020-09-18. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Flieger, Verlyn (2011). "Sometimes One Word is Worth a Thousand Pictures". In Bogstad, Janice M.; Kaveny, Philip E. (eds.). Picturing Tolkien. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-7864-8473-7. Archived from the original on 2020-09-21. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- "Sala Baker". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- Langford, Barry (2013) [2007]. "Bakshi, Ralph (1938–)". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Abingdon, England: Taylor & Francis. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0. Archived from the original on 2020-08-02. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- "The Eye of Sauron – J.R.R. Tolkien's The Return of the King". Archived from the original on 2017-06-01. Retrieved 2006-10-13.

- Vejvoda, Jim (31 July 2020). "Lord of the Rings: Amazon Series Reportedly Includes Sauron, Galadriel, and Elrond". IGN. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

The villainous Sauron was played in humanoid form by Sala Baker, while Alan Howard voiced the antagonist in The Lord of the Rings

- Harl, Allison (Spring–Summer 2007). "The monstrosity of the gaze: critical problems with a film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings". Mythlore. 25 (3). Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- Stauffer, Derek (10 August 2017). "Lord Of The Rings: 15 Deleted Scenes You Won't Believe Were Cut". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Child, Ben (6 January 2012). "Hobbit forming: will Peter Jackson give Tolkien's story a new ending?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Busch, Caitlin (February 10, 2017). "The 9 Most Surprising Cameos in 'Lego Batman'". Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Busch, Caitlin (February 10, 2017). "'LEGO Batman' Crosses over with 'Harry Potter,' 'Doctor Who,' and 'Lord of the Rings'". Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Otterson, Joe (19 January 2022). "'Lord of the Rings' Amazon Series Reveals Full Title in New Video". Variety. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- Hibberd, James (13 October 2022). "'The Rings of Power' Finale: Even Sauron Actor Didn't Know He Was Sauron at First". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- Power, Ed (17 January 2020). "The battle of Middle Earth: how Christopher Tolkien fought Peter Jackson over The Lord of the Rings". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Sammut, Mark (23 July 2018). "Every Single The Lord Of The Rings Video Game, Officially Ranked". Thegamer. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Bainbridge, William Sims (September 2010). "Virtual Nature: Environmentalism in Two Multi-player Online Games". Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature & Culture. 4 (3): 135–152. doi:10.1558/jsrnc.v4i3.135.

- King, Stephen (1978). The Stand: The Complete & Uncut Edition. New York City: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-12168-2.

- Magistrale, Tony (21 December 2009). Stephen King: America's Storyteller. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. p. 40. ISBN 978-0313352287. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- Roy Thomas (w), Neal Adams (p), Tom Palmer (i), Sam Rosen (let), Stan Lee (ed). "In the Shadow of...Sauron!" The X-Men, vol. 1, no. 60 (September 1969). New York City: Marvel Comics.

- O'Shea, Tom (2003). ""This is a Wonderful Job": An Orca Q&A with Fables' Bill Willingham". Archived from the original on 29 April 2005. Retrieved 31 July 2007. Interview with Bill Willingham

Sources

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2.

- Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (1995). J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator. Illustrated by J. R. R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-74816-X.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954). The Two Towers. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1042159111.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales. Vol. 1. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-35439-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984b). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales. Vol. 2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-36614-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Lost Road and Other Writings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-45519-7.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1993). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Morgoth's Ring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-68092-1.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1992). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Sauron Defeated. Boston, New York, & London: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-60649-7.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1994). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The War of the Jewels. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-71041-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Peoples of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-82760-4.