Orc

An orc (sometimes spelt ork; /ɔːrk/[1][2]),[3] in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth fantasy fiction, is a race of humanoid monsters, which he also calls "goblin".

Especially in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, orcs appear as a brutish, aggressive, ugly, and malevolent race of monsters, contrasting with the benevolent Elves. They are a corrupted race of elves, either bred that way by Morgoth, or turned savage in that manner, according to the Silmarillion.[4][5]

The orc was a sort of "hell-devil" in Old English literature, and the orc-né (pl. orc-néas, "demon-corpses") was a race of corrupted beings and descendants of Cain, alongside the elf, according to the poem Beowulf. Tolkien adopted the term orc from these old attestations, which he professed was a choice made purely for "phonetic suitability" reasons.[T 1]

Tolkien's concept of orcs has been adapted into the fantasy fiction of other authors, and into games of many different genres such as Dungeons & Dragons, Magic: The Gathering, and Warcraft.

Etymology

The word orc probably derives from the Latin word/name Orcus.[6] The term orcus is glossed as "orc, þyrs, oððe hel-deofol"[lower-alpha 1] ("Goblin, spectre, or hell-devil") in the 10th century Old English Cleopatra Glossaries, about which Thomas Wright wrote, "Orcus was the name for Pluto, the god of the infernal regions, hence we can easily understand the explanation of hel-deofol. Orc, in Anglo-Saxon, like thyrs, means a spectre, or goblin."[7][8][lower-alpha 2]

In the sense of a monstrous being, the term is used just once in Beowulf, as the plural compound orcneas, one of the tribes belonging to the descendants of Cain, alongside the elves and ettins (giants) condemned by God:

—Beowulf, Fitt I, vv. 111–14[9] |

—John R. Clark Hall, tr. (1901)[10] |

The meaning of Orcneas is uncertain. Frederick Klaeber suggested it consisted of orc < L. orcus "the underworld" + neas "corpses", to which the translation "evil spirits" failed to do justice.[11][lower-alpha 3] It is generally supposed to contain an element -né, cognate to Gothic naus and Old Norse nár, both meaning 'corpse'.[6][lower-alpha 4] If *orcné is to be glossed as orcus 'corpse', then the compound word can be construed as "demon-corpses",[13] or "corpse from Orcus (i.e. the underworld)".[11] Hence orc-neas may have been some sort of walking dead monster, a product of ancient necromancy,[11] or a zombie-like creature.[13][14]

Tolkien

The term "orc" is used only once in the first edition of Tolkien's 1937 The Hobbit, which preferred the term "goblins". "Orc" was later used ubiquitously in The Lord of the Rings.[15][T 2] The "orc-" element occurs in the sword name Orcrist,[lower-alpha 5][T 2][15] which is given as its Elvish language name,[T 3][16] and it is glossed as "Goblin-cleaver".[T 4]

Stated etymology

Tolkien began the more modern use of the English term "orc" to denote a race of evil, humanoid creatures. His earliest Elvish dictionaries include the entry Ork (orq-) "monster", "ogre", "demon", together with orqindi and "ogresse". He sometimes used the plural form orqui in his early texts.[lower-alpha 6] He stated that the Elvish words for orc were derived from a root ruku, "fear, horror"; in Quenya, orco, plural orkor; in Sindarin orch, plurals yrch and Orchoth (as a class).[T 5][T 1] They had similar names in other Middle-earth languages: uruk in Black Speech;[T 1] in the language of the Drúedain gorgûn, "ork-folk"; in Khuzdul rukhs, plural rakhâs; and in the language of Rohan and in the Common Speech, orka.[T 5]

Tolkien stated in a letter to the novelist Naomi Mitchison that his orcs had been influenced by George MacDonald's The Princess and the Goblin.[T 1] He explained that his "orc" was "derived from Old English orc 'demon', but only because of its phonetic suitability",[T 1][15] and

I originally took the word from Old English orc (Beowulf 112 orc-neas and the gloss orc: þyrs ('ogre'), heldeofol ('hell-devil')).[lower-alpha 7] This is supposed not to be connected with modern English orc, ork, a name applied to various sea-beasts of the dolphin order".[T 6][1]

Tolkien also observed a similarity with the Latin word orcus, noting that "the word used in translation of Q[uenya] urko, S[indarin] orch is Orc. But that is because of the similarity of the ancient English word orc, 'evil spirit or bogey', to the Elvish words. There is possibly no connection between them".[T 5]

Description

Orcs are of human shape, and of varying size.[T 7] They are depicted as ugly and filthy, with a taste for human flesh. They are fanged, bow-legged and long-armed. Most are small and avoid daylight.[T 8]

By the Third Age, a new breed of orc had emerged, the Uruk-hai, larger and more powerful, and no longer afraid of daylight.[T 8] Orcs eat meat, including the flesh of Men, and may indulge in cannibalism: in The Two Towers, Grishnákh, an orc from Mordor, claims that the Isengard orcs eat orc-flesh. Whether that is true or spoken in malice is uncertain: an orc flings Peregrin Took stale bread and a "strip of raw dried flesh... the flesh of he dared not guess what creature".[T 8]

Half-orcs appear in The Lord of the Rings, created by interbreeding of orcs and Men;[T 9] they were able to go in sunlight.[T 8] The "sly Southerner" in The Fellowship of the Ring looks "more than half like a goblin";[T 10] similar but more orc-like hybrids appear in The Two Towers "man-high, but with goblin-faces, sallow, leering, squint-eyed."[T 11]

In Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films, the actors playing orcs are made up with masks designed to make them look evil. After a disagreement with the film producer Harvey Weinstein, Jackson had one of the masks made to resemble Weinstein, as an insult to him.[17]

Orkish language

The Orcs had no language of their own, merely a pidgin of many various languages. However, individual tribes developed dialects that differed so widely that Westron, often with a crude accent, was used as a common language.[T 8] When Sauron returned to power in Mordor in the Third Age, Black Speech was used by the captains of his armies and by his servants in Barad-dûr. A sample of debased Black Speech can be found in The Two Towers, where a "yellow-fanged" guard Orc of Mordor curses Uglúk of Isengard (an uruk-hai chief) with the words "Uglúk u bagronk sha pushdug Saruman-glob búbhosh skai!" In The Peoples of Middle-earth, Tolkien gives the translation: "Uglúk to the cesspool, sha! the dungfilth; the great Saruman-fool, skai!"[T 12] However, in a note published in Vinyar Tengwar he gives an alternative translation: "Uglúk to the dung-pit with stinking Saruman-filth, pig-guts, gah!"[19] Alexander Nemirovsky speculated that Tolkien might have drawn upon the language of the ancient Hittites and Hurrians for Black Speech.[20]

In-fiction origins

The origin(s) of orcs were explained two different ways (i.e., inconsistently) by Tolkien:[5] the orcs were either East Elves (Avari) enslaved, tortured, and bred by Morgoth (as Melkor became known),[T 13] or, "perhaps.. Avari [(a race of elves)].. [turned] evil and savage in the wild", both according to The Silmarillion.[T 14][lower-alpha 8]

The orcs "multiplied" like Elves and Men, meaning that they reproduced sexually.[21] Tolkien stated in a letter dated 21 October 1963 to a Mrs. Munsby that "there must have been orc-women".[T 16][22][23] In The Fall of Gondolin Morgoth made them of slime by sorcery, "bred from the heats and slimes of the earth".[T 17] Or, they were "beasts of humanized shape", possibly, Tolkien wrote, Elves mated with beasts, and later Men.[T 18] Or again, Tolkien noted, they could have been fallen Maiar, perhaps a kind called Boldog, like lesser Balrogs; or corrupted Men.[T 9]

Shippey writes that the orcs in The Lord of the Rings were almost certainly created just to equip Middle-earth with "a continual supply of enemies over whom one need feel no compunction",[21] or in Tolkien's words from The Monsters and the Critics "the infantry of the old war" ready to be slaughtered.[21] Shippey states that all the same, orcs share the human concept of good and evil, with a familiar sense of morality, though he notes that, like many people, orcs are quite unable to apply their morals to themselves. In his view, Tolkien, as a Catholic, took it as a given that "evil cannot make, only mock", so orcs could not have an equal and opposite morality to that of men or elves.[24] In a 1954 letter, Tolkien wrote that orcs were "fundamentally a race of 'rational incarnate' creatures, though horribly corrupted, if no more so than many Men to be met today."[T 19] The scholar of English literature Robert Tally wrote in Mythlore that despite the uniform presentation of orcs as "loathsome, ugly, cruel, feared, and especially terminable", "Tolkien could not resist the urge to flesh out and 'humanize' these inhuman creatures from time to time", in the process giving them their own morality.[25] Shippey notes that in The Two Towers, the orc Gorbag disapproves of the "regular elvish trick"–an immoral act–of seeming to abandon a comrade, as he wrongly supposes Sam Gamgee has done with Frodo Baggins. Shippey describes the implied view of evil as Boethian, that evil is the absence of good. He notes, however, that Tolkien did not agree with that point of view; Tolkien believed that evil had to be actively fought, with war if necessary, something that Shippey describes as representing the Manichean position, that evil coexists with good and is at least equally powerful.[26]

| Created evil | Like animals | Created good, but fallen | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin of orcs according to Tolkien |

"Brooded" by Morgoth[T 15] | "Beasts of humanized shape"[T 18] | Fallen Maiar, or corrupted Men/Elves[T 13][T 9] |

| Moral implication | Orcs are wholly evil (unlike Men) and can be slaughtered without compunction[21] | Orcs have no morality, no power of speech, are not sentient | Orcs have morality just like Men[26][25] |

| Resulting problem | Orcs like Gorbag have a moral sense (even if they cannot keep to it) and can speak, which conflicts with their being wholly evil or not even sentient. Since evil cannot make, only mock, orcs cannot have an equal and opposite morality to Men.[25][24] | It's wrong just to slaughter them, then | |

Debated racism

The possibility of racism in Tolkien's descriptions of orcs has been debated. In a private letter, Tolkien describes orcs as:[T 20]

squat, broad, flat-nosed, sallow-skinned, with wide mouths and slant eyes: in fact degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-types.[T 20]

O'Hehir describes orcs as "a subhuman race bred by Morgoth and/or Sauron (although not created by them) that is morally irredeemable and deserves only death. They are dark-skinned and slant-eyed, and although they possess reason, speech, social organization and, as Shippey mentions, a sort of moral sensibility, they are inherently evil."[28] He notes Tolkien's own description of them, saying it could scarcely be more revealing as a representation of the "Other", and states "it is also the product of his background and era, like most of our inescapable prejudices. At the level of conscious intention, he was not a racist or an anti-Semite" and mentions Tolkien's letters to this effect.[28] The literary critic Jenny Turner, writing in the London Review of Books, endorses Andrew O'Hehir's comment on Salon.com that orcs are "by design and intention a northern European's paranoid caricature of the races he has dimly heard about".[29][28]

Tally describes the orcs as a demonized enemy, despite (he writes) Tolkien's own objections to demonization of the enemy in the two World Wars.[30] In a letter to his son, Christopher, who was serving in the RAF in the Second World War, Tolkien wrote of orcs as appearing on both sides of the conflict:

Yes, I think the orcs as real a creation as anything in 'realistic' fiction ... only in real life they are on both sides, of course. For 'romance' has grown out of 'allegory', and its wars are still derived from the 'inner war' of allegory in which good is on one side and various modes of badness on the other. In real (exterior) life men are on both sides: which means a motley alliance of orcs, beasts, demons, plain naturally honest men, and angels.[T 21]

John Magoun, writing in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, states that Middle-earth has a "fully expressed moral geography".[27] Any moral bias towards a north-western geography, however, was directly denied by Tolkien in a letter to Charlotte and Denis Plimmer, who had recently interviewed him in 1967:

Auden has asserted that for me 'the North is a sacred direction'. That is not true. The North-west of Europe, where I (and most of my ancestors) have lived, has my affection, as a man's home should. I love its atmosphere, and know more of its histories and languages than I do of other parts; but it is not 'sacred', nor does it exhaust my affections. I do have, for instance, a particular fondness for the Latin language, and among its descendants for Spanish. That it is untrue for my story, a mere reading of the synopses should show. The North was the seat of the fortresses of the Devil [ie. Morgoth].[T 22]

Scholars of English literature William N. Rogers II and Michael R. Underwood note that a widespread element of late 19th century Western culture was fear of moral decline and degeneration; this led to eugenics.[32] In The Two Towers, the Ent Treebeard says:[T 23]

It is a mark of evil things that came in the Great Darkness that they cannot abide the Sun; but Saruman's orcs can endure it, even if they hate it. I wonder what he has done? Are they Men he has ruined, or has he blended the races of orcs and Men? That would be a black evil![T 23]

The Germanic studies scholar Sandra Ballif Straubhaar however argues against the "recurring accusations" of racism, stating that "a polycultured, polylingual world is absolutely central" to Middle-earth, and that readers and filmgoers will easily see that.[33] The historian and Tolkien scholar Jared Lobdell likewise disagreed with any notions of racism inherent or latent in Tolkien's works, and wondered "if there were a way of writing epic fantasy about a battle against an evil spirit and his monstrous servants without its being subject to speculation of racist intent".[34]

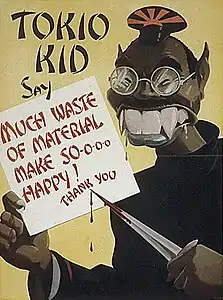

The journalist David Ibata writes that the interpretations of orcs in Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films look much like "the worst depictions of the Japanese drawn by American and British illustrators during World War II".[31]

Other fiction

As a response to the type-casting of orcs as generic evil characters or antagonists, some novels portray events from the point of view of the orcs, or make them more sympathetic characters. Mary Gentle's 1992 novel Grunts! presents orcs as generic infantry, used as metaphorical cannon-fodder. A series of books by Stan Nicholls, Orcs: First Blood, focuses on the conflicts between orcs and humans from the orcs' point of view.[35] In Terry Pratchett's Discworld series, orcs are close to extinction; in his Unseen Academicals it is said that "When the Evil Emperor wanted fighters he got some of the Igors to turn goblins into orcs" to be used as weapons in a Great War, "encouraged" by whips and beatings.[36]

In games

Orcs based on The Lord of the Rings have become a fixture of fantasy fiction and role-playing games.

Dungeons & Dragons

In the fantasy tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), orcs are creatures in the game, and somewhat based upon those described by Tolkien.[37] These D&D orcs are implemented in the game rules as a multi-tribed race of hostile and bestial humanoids.[38][40][41]

The D&D orcs are endowed with muscular frames, large canine teeth like boar's tusks, and snouts rather than human-like noses.[41][39] While a pug-nose ("flat-nosed"[T 20]) was attributable to Tolkien's written correspondence, the pig-headed (pig-faced[42]) look was imparted on the orc by the D&D original edition (1974).[43] It was later modified from bald-headed to hairy in subsequent editions.[43] In the third version of the game the orc became gray-skinned,[44][45][46] even though a complicated color-palleted description of a (non-gray) orc had been implemented in the Monster Manual for the first edition (1977).[47] Newer versions seem to have dropped references to skin-color.[39]

Early versions of the game introduced the "half-orc" as race.[48] The orc was described in the first edition of Monster Manual (op. cit.), as a fiercely competitive bully, a tribal creature often dwelling and building underground;[49] in newer editions, orcs (though still described as sometimes inhabiting cavern complexes) had been shifted to become more prone to non-subterranean habitation as well, adapting captured villages into communities, for instance.[50][39] The mythology and attitudes of the orcs are described in detail in Dragon #62 (June 1982), in Roger E. Moore's article, "The Half-Orc Point of View".[51]

The orc for the D&D offshoot Pathfinder RPG are detailed in the 2008 book Classic Monsters Revisited issued by the game's publisher Paizo.[52]

Warhammer

Games Workshop's Warhammer universe features cunning and brutal Orks in a fantasy setting, who are driven not so much by a need to do evil as to obtain fulfilment through the act of war.[53] In the Warhammer 40,000 series of science-fiction games, they are a green-skinned alien species, called Orks.[54]

Warcraft

Orcs are an important race in Warcraft, a high fantasy franchise created by Blizzard Entertainment.[55] Several orc characters from the Warcraft universe are playable heroes in the crossover multiplayer game Heroes of the Storm.[56]

Other products

The orc features in numerous Magic: The Gathering collectible cards, in the 1993 game series published by Wizards of the Coast.[lower-alpha 9][57]

In The Elder Scrolls series, many orcs or Orsimer are skilled blacksmiths.[58] In Hasbro's Heroscape products, orcs come from the pre-historic planet Grut.[59] They are blue-skinned, with prominent tusks or horns.[60] The Skylander Voodood from the first game in the series, Skylanders: Spyro's Adventure, is an orc.[61]

Savage orc

Savage orc For the Love of Waaagh!, an Ork from Warhammer 40,000

For the Love of Waaagh!, an Ork from Warhammer 40,000 Orc Grunt, an orc from Warcraft

Orc Grunt, an orc from Warcraft

See also

- Haradrim – the dark-skinned "Southrons" who fought for Sauron alongside the orcs

- Troll (Middle-earth) – large humanoids of great strength and poor intellect, also used by Sauron

Notes

- Here: "orcus [orc].. þrys ꝉ heldeofol" is the redaction given by Pheifer 1974, p. 37n but þrys appears to be a mistranscription for þyrs. The original text uses "ꝉ", the scribal abbreviation for Latin vel meaning "or", which Wright has silently expanded as Anglo-Saxon oððe.

- The Corpus Glossary (Corpus Christi College MS. 144, late 8th to early 9th century) has the two glosses: "orcus, orc" and "orcus, ðyrs, hel-diobul.Pheifer 1974, p. 37n

- Klaeber here takes orcus to be the world and not the god, as does Bosworth & Toller 1898, p. 764: "orc, es; m. The infernal regions (orcus)", though the latter seems to predicate on synthesizing the compound "Orcþyrs" by altering the reading of the Cleopatra glossaries as given by Wright's Voc. ii. that he sources.

- The usual Old English word for corpse is líc, but -né appears in nebbed 'corpse bed',[12] and in dryhtné 'dead body of a warrior', where dryht is a military unit.

- Thorin Oakenshield's Elvish sword from Gondolin.

- Parma Eldalamberon volume XII: "Quenya Lexicon Quenya Dictionary": 'Ork' ('orq-') monster, ogre, demon. "orqindi" ogresse. [The original reading of the second entry was >'orqinan' ogresse.< Perhaps the intended meaning of the earlier form was 'region of ogres'; cf. 'kalimban', 'Hisinan'. 'The Poetic and Mythologic Words of Eldarissa' gives 'ork' 'ogre, giant' and 'orqin' 'ogress', which may be a feminine form. ...]"

- In the Cleopatra Glossaries, Folio 69 verso; the entry is illustrated above.

- The orcs are described as "foul broodlings of Melkor who fared abroad doing his evil work" in The Tale of Tinúviel.[T 15]

- Wizards of the Coast acquired TSR in 1997, and subsequently published editions of D&D and Monster Manual.

References

Primary

- Carpenter 1981, #144 to Naomi Mitchison 25 April 1954

- Tolkien 1937, p. 149, n9

- Tolkien 1937, p. 62, n4

- Tolkien 1937, ch. 4 "Over Hill and Under Hill"

- Tolkien 1994, Appendix C "Elvish names for the Orcs", pp. 289–391

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2005). "Nomenclature of The Lord of the Rings" (PDF). In Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (eds.). The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-720907-1.

- Tolkien 1955 book 6, ch. 1, "The Tower of Cirith Ungol"

- Tolkien 1954, Book 3, ch. 3 "The Uruk-hai"

- Tolkien 1993, "Myths transformed", text X

- Tolkien 1954a, Book 1, ch. 11 "A Knife in the Dark"

- Tolkien 1954, Book 3, ch. 9 "Flotsam and Jetsam"

- Tolkien 1996, Part One: the Prologue and Appendices to The Lord of the Rings. Draft of Appendix F.

- Tolkien 1977, p. 50

- Tolkien 1977, pp. 93–94

- Tolkien 1984b, "The Tale of Tinúviel"

- Tolkien (1963). Letter dated 21 October 1963 to Ms. Munsby, cited in Gee, Henry. "The Science of Middle-earth: Sex and the Single Orc". TheOneRing.net. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- Tolkien 1984b, p. 159

- Tolkien 1993, "Myths transformed", text VIII

- Carpenter 1981, letter 153 to Peter Hastings, draft, September 1954

- Carpenter 1981, #210

- Carpenter 1981, #71

- Carpenter 1981, #294

- Tolkien 1954, Book 3, Ch. 4, "Treebeard"

Secondary

- Karthaus-Hunt, Beatrix (2002). "'And What Happened After': How J.R.R. Tolkien Visualized, and Other Artists Re-Visualized, the Denizens of Middle-earth". In Westfahl, Gary; Slusser, George Edgar; Plummer, Kathleen Church (eds.). Unearthly Visions: Approaches to Science Fiction and Fantasy Art. Greenwood Press. pp. 138n. ISBN 0313317054.

- Lobdell 1975, p. 171.

- "Orc". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 362, 438 (chapter 5, note 14).

- Schneidewind, Friedhelm (2007). "Biology of Middle-earth". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-4159-6942-0.

- Shippey, Tom (1979). "Creation from Philology in the Lord of the Rings". In Salu, Mary; Farrell, Robert T. (eds.). J. R. R. Tolkien, scholar and storyteller: Essays in Memoriam. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-80141-038-3.

- Wright, Thomas (1873). A second volume of vocabularies. privately printed. p. 63.

- Pheifer, J. D. (1974). Old English Glosses in the Épinal-Erfurt Glossary. Oxford University Press. pp. 37, 106. ISBN 978-0-19-811164-1.(Repr. Sandpaper Books, 1998 ISBN 0-19-811164-9), Gloss #698: orcus orc (Épinal); orci orc (Erfurt).

- Klaeber 1950, p. 5.

- Klaeber 1950, p. 25

- Klaeber 1950, p. 183: "orcneas: 'evil spirits' does not bring out all the meaning. Orcneas is compounded of orc (from the Lat. orcus "the underworld" or Hades) and neas "corpses". Necromancy was practised among the ancient Germani and was familiar among the pagan Norsemen who revived it in England when they invaded".

- Brehaut, Patricia Kathleen (1961). Moot passages in Beowulf (Thesis). Stanford, California: Stanford University. p. 8.

- Shippey 2001, p. 88.

- Beowulf: A Dual-language Edition. Translated by Chickering, Howell D. Anchor books. 1977. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-3850-6213-8.

- Gilliver, Peter; Marshall, Jeremy; Weiner, Edmund (2009). "Part III. Word Studies. Orc.". The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. pp. 174–175. ISBN 9780199568369.

- Kemball-Cook, Jessica (February 1977). "Three Notes on Names in Tolkien and Lewis". Mythprint. 15 (2): 2.

- Oladipo, Gloria (5 October 2021). "Lord of the Rings orc was modeled after Harvey Weinstein, Elijah Wood reveals". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- Hostetter, Carl F. (November 1992). "Ugluk to the Dung-pit". Vinyar Tengwar. The Elvish Linguistic Fellowship (26).

- Fauskanger, Helge K. "Orkish and the Black Speech – base language for base purposes". Ardalambion. University of Bergen. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- Shippey 2005, p. 265

- Chausse, Jean (2016). "Le pouvoir féminin en Arda". In Qadri, Jean-Philippe; Sainton, Jérôme (eds.). Pour la gloire de ce monde. Recouvrements et consolations en Terre du Milieu (in French). Le Dragon de Brume. p. 160, n7. ISBN 9782953989649.

- Stuart 2022, p. 133.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 362, 438 (chapter 5, note 14)

- Tally, Robert T. Jr. (2010). "Let Us Now Praise Famous Orcs: Simple Humanity in Tolkien's Inhuman Creatures". Mythlore. 29 (1). article 3.

- Shippey 2001, pp. 131–133.

- Magoun, John F. G. (2006). "South, The". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 622–623. ISBN 1-135-88034-4.

- O'Hehir, Andrew (6 June 2001). "A curiously very great book". Salon.com. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Turner, Jenny (15 November 2001). "Reasons for Liking Tolkien". London Review of Books. 23 (22).

- Tally, Robert (2019). "Demonizing the Enemy, Literally: Tolkien, Orcs, and the Sense of the World Wars". Humanities. 8 (1): 54. doi:10.3390/h8010054. ISSN 2076-0787.

- Ibata, David (12 January 2003). "'Lord' of racism? Critics view trilogy as discriminatory". The Chicago Tribune.

- Rogers, William N., II; Underwood, Michael R. (2000). Sir George Clark (ed.). Gagool and Gollum: Exemplars of Degeneration in King Solomon's Mines and The Hobbit. pp. 121–132. ISBN 978-0-313-30845-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2004). "Myth, Late Roman History, and Multiculturalism in Tolkien's Middle-Earth". In Chance, Jane (ed.). Tolkien and the invention of myth : a reader. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 101–117. ISBN 978-0-8131-2301-1.

- Lobdell, Jared (2004). The World of the Rings. Open Court. p. 116. ISBN 978-0875483030.

- "Stan Nicholls". Fantasticfiction.co.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- Pratchett, Terry (2009). Unseen Academicals. Doubleday. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-3856-0934-0.

- "'Orc' (from Orcus) is another term for an ogre or ogre-like creature. Being useful fodder for the ranks of bad guys, monsters similar to Tolkien's orcs are also in both games." Gygax, Gary (March 1985). "On the influence of J.R.R. Tolkien on the D&D and AD&D games". The Dragon. No. 95. pp. 12–13.

- Williams, Skip; Tweet, Jonathan; Cook, Monte (1 October 2000). Monster Manual: Core Rulebook III (3 ed.). Wizards of the Coast. p. 146. ISBN 0-7869-1552-8.

Orcs are aggressive humanoids that raid, pillage, and battle other creatures

apud MacCallum-Stewart (2008), p. 41 - Crawford, Jeremy, ed. (July 2003). Monster Manual: Dungeons & Dragons Core Rulebook. Co-lead design by Mike Mearls (5 ed.). Wizards of the Coast. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-7869-6561-8.

- "Orcs gather in tribes that exert their dominance and satisfy their bloodlust by plundering villages, devouring or driving off roaming herd, and slaying any humanoids that stand against them".[39] quoted by Young (2015), p. 96.

- Mohr, Joseph (7 December 2019). "Orcs in Dungeons and Dragons". Old School Role Playing. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Pramas, Chris (2017). Orc Warfare. New York: Rosen Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-5081-7624-4.

- Mitchell-Smith (2009), p. 219.

- Williams, Skip; Tweet, Jonathan; Cook, Monte (1 October 2000). Monster Manual: Core Rulebook III (3 ed.). Wizards of the Coast. p. 146. ISBN 0-7869-1552-8.

orcs... look like primitive humans with gray skin, coarse hair, stooped postures, low foreheads, and porcine faces with prominent lower canines... they have lupine ears.

apud Young (2015), p. 95 - Williams, Skip; Tweet, Jonathan; Cook, Monte (July 2003). Monster Manual: Dungeons & Dragons Core Rulebook (3.5 ed.). Wizards of the Coast. p. 203. ISBN 0-7869-2893-X.

[The Creature] looks like a primitive human with gray skin and coarse hair. It has a stooped posture, low forehead, and a piglike face with prominent lower canines that resemble a boar's tusks.

apud Mitchell-Smith (2009), p. 216 - And the "Gray orc" introduced as a race.[41]

- Gygax, Gary (December 1977). Monster Manual (1 ed.). TSR. p. 76.

Orcs appear particularly disgusting because their coloration ― brown or brownish green with bluish sheen ― highlights their pinkish snouts and ears. Their bristly hair is dark brown or black, sometimes with tan patches.

- Either the D&D first edition[41] or Advanced D&D,[43]

- Gygax, Gary (1977) Monster Manual, TSR. Also Young (2015), p. 97, citing this and subsequent editions of MM.

- Young (2015), p. 97.

- Moore, Roger E. "The Half-Orc Point of View." Dragon #62 (TSR, June 1982).

- Baur, Wolfgang, Jason Bulmahn, Joshua J. Frost, James Jacobs, Nicolas Logue, Mike McArtor, James L. Sutter, Greg A. Vaughan, Jeremy Walker. Classic Monsters Revisited (Paizo, 2008) pages 52–57.

- Priestley, Rick; Thornton, Jake (2000). Warhammer Fantasy Battles Army Book: Orcs & Goblins (6th ed.). Games Workshop: Nottingham. pp. 10–11.

- Sanders, Rob. "Xenos: Seven Alien Species With A Shot At Conquering the 40k Galaxy". Rob Sanders Speculative Fiction. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- MacCallum-Stewart (2008), pp. 39–62.

- "Another orc enters the Heroes of the Storm battleground". Destructoid. 6 October 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Vessenes, Ted (8 February 2002). "Lessons of the Past". The One Ring. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- Stewart, Charlie (14 September 2020). "Why the Orcs Could Have a Huge Role in The Elder Scrolls 6". GameRant. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- "Blade Gruts". Hasbro.com. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- "Heavy Gruts". Hasbro.com. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Ronaghan, Neal. "Skylanders Giants Character Guide Magic Element Characters From Spyro's Adventure". Nintendo World Report. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

Sources

- Bosworth, Joseph; Toller, T. Northcote (1898). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Vol. 1 A-Fir. Clarendon Press. p. 764.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2.

- Klaeber, Friedrich (1950). Beowulf and the Finnesburg Fragment. Translated by John R. Clark Hall (3 ed.). Allen & Unwin.

- Lobdell, Jared, ed. (1975). A Tolkien Compass. Open Court. ISBN 9780875483160.

- MacCallum-Stewart, Esther (2008). "2: 'Never Such Innocence Again': War and Histories in World of Warcraft". In Corneliussen, Hilde; Rettberg, Jill Walker (eds.). Digital Culture, Play, and Identity: A World of Warcraft Reader. MIT Press. pp. 39–62. ISBN 9780262033701.

- Mitchell-Smith, Ilan (May 2009). "11: Racial Determinism and the Interlocking Economics of Power and Violence in Dungeons & Dragons". In Harden, B. Garrick; Carley, Robert (eds.). Co-opting Culture. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-7391-2597-7.

- Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261-10401-3.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Stuart, Robert (2022). Tolkien, Race, and Racism in Middle-earth. Springer Nature. ISBN 9783030974756.

- Young, Helen (2015). "4. Orcs and Otherness: Monsters on Page and Screen". Race and Popular Fantasy Literature: Habits of Whiteness. Taylor & Francis. pp. 88–113. ISBN 9781317532170.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). Douglas A. Anderson (ed.). The Annotated Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002). ISBN 978-0-618-13470-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954). The Two Towers. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1042159111.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984b). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales. Vol. 2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-36614-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1993). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Morgoth's Ring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-68092-1.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1994). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The War of the Jewels. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-71041-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Peoples of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-82760-4.

.jpg.webp)