Vädersolstavlan

Vädersolstavlan (Swedish for 'The Sundog Painting'; ⓘ) is an oil-on-panel painting depicting a halo display, an atmospheric optical phenomenon, observed over Stockholm on 20 April 1535. It is named after the sun dogs (Swedish: Vädersol, lit. 'weather sun') appearing on the upper right part of the painting. While chiefly noted for being the oldest depiction of Stockholm in colour,[1] it is arguably also the oldest Swedish landscape painting and the oldest depiction of sun dogs.

| Vädersolstavlan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Urban målare, Jacob Elbfas |

| Year | 1535, 1636 |

| Medium | Oil-on-panel |

| Dimensions | 163 cm × 110 cm (64 in × 43 in) |

| Location | Storkyrkan, Stockholm |

The original painting, which was produced shortly after the event and traditionally attributed to Urban målare ("Urban [the] Painter"), is lost, and virtually nothing is known about it. However, a copy from 1636 by Jacob Heinrich Elbfas held in Storkyrkan in Stockholm is believed to be an accurate copy and was until recently erroneously thought to be the restored original. It was previously covered by layers of brownish varnish, and the image was hardly discernible until carefully restored and thoroughly documented in 1998–1999.

The painting was produced during an important time in Swedish history. The establishment of modern Sweden coincided with the introduction of Protestantism and the break-up with Denmark and the Kalmar Union. The painting was commissioned by the Swedish reformer Olaus Petri, and the resulting controversies between him and King Gustav Vasa and the historical context remained a well-kept secret for centuries. During the 20th century the painting became an icon for the history of Stockholm and it is now frequently displayed whenever the history of the city is commemorated.

Painting

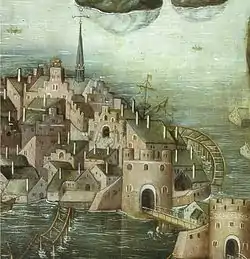

The painting is divided into an upper part depicting the halo phenomenon viewed vertically and a lower part depicting the city as it must have appeared viewed from Södermalm in the late Middle Ages. The medieval urban conglomeration, today part of the old town Gamla stan, is rendered using a bird's-eye view. The stone and brick buildings are densely packed below the church and castle, which are rendered in a descriptive perspective (i.e., their size relates to their social status, rather than their actual dimensions). Scattered wooden structures appear on the surrounding rural ridges, today part of central Stockholm. Though the phenomenon is said to have occurred in the morning, the city is depicted in the evening with shadows facing east.[2]

The wooden panel measures 163 by 110 centimetres (64 by 43 inches) and is composed of five vertical deals (softwood planks) reinforced by two horizontal dovetail battens. The battens, together with the rough scrub planed back, have effectively reduced warping to a minimum and the artwork is well preserved, with only insignificant fissures and attacks by insects.[3] A dendrochronological examination of the panel by doctor Peter Klein at the Institute für Holzbiologie in Hamburg determined that it is made of pine deals (Pinus silvestris), the annual rings of which date from various periods ranging from the 1480s to around 1618. The painting can therefore date no further back than around 1620. This is consistent with the year 1636 given on the frame and mentioned in the parish accounts.[4]

The dye, covering a semi-transparent red-brownish bottom layer, is emulsion paint containing linseed oil. The painting was apparently painted detail by detail as no under-painting or preparatory sketches have been discovered, except for marks at the centres of the biggest circles indicating that compasses were used. As a result of this, the horizon tilts to the right; an x-ray analysis has shown that the painter tried to compensate for this tilt by altering various elements in the painting, including mountains added along the horizon and the gently leaning spires of the church and the castle. A narrow unpainted border has been left around the image.[5]

Possible prototypes

No prototypes for the painting are known in Sweden, and while the painting is occasionally associated with the Danube school, much about its stylistic and iconographic history remains to be investigated. A possible stylistic prototype is the illustrated Bible of Erhard Altdorfer (brother of the more famous Albrecht Altdorfer). Begun in 1530, it was inspired by the works of Cranach and Dürer, but also renewed the genre by combining commonplace details with an undertone of approaching disaster. In particular, Altdorfer's apocalyptic illustrations for the Revelation to John deliver an evangelic message similar to that of the Vädersolstavlan. Historical documents show that Olaus Petri, who commissioned the painting, combined biblical quotations related to the Apocalypse with the painting hanging in the church. Copies of Erhard Altdorfer's apocalyptic woodcuts may have been available in Stockholm through the German merchant Gorius Holste who lived by Järntorget square and who was a friend of both Petri and Martin Luther.[6]

In Albrecht Altdorfer's The Battle of Alexander at Issus, one of the most famous paintings produced by the Danube School, a composition similar to Vädersolstavlan renders the battle scene in a detailed landscape under a sky crowded with celestial symbols and messages. Just as in Vädersolstavlan, the view is not depicted as it would really appear, but is rather a composite of factual elements as known by the artist. In The Battle of Alexander at Issus the eastern Mediterranean Sea, Africa, and the Nile River are represented as known from contemporary maps, while the knights and soldiers are dressed in 16th century armours and the battle is depicted as retold in sources from Antiquity. The frame suspended over the scene, a device which appears in many other German Renaissance battle scenes, is mirrored by the 17th century inscription in Vädersolstavlan. In both paintings, Apocalyptic symbols in the sky are given a contemporary political significance. The realistically rendered sky, light, and clouds, in both paintings, are emblematic of the Danube School.[7]

17th-century copy and modern restorations

Before and ... |

... after restoration |

|

Above: The painting before (left) and after restoration (right).

| |

|

ANNO DM 1535

| |

The lost original painting is attributed to Urban Målare by tradition. However, historical sources and other works of art from the early Vasa Era are rare, and this attribution is apparently doubtful. Furthermore, as the extant painting has proven to be a 17th-century copy, and not as previously believed a restored original, a credible corroboration is unlikely to ever be produced.[8]

In the parish accounts, the painting is first mentioned in 1636, at which time a "M. Jacob Conterfeyer" was recorded as having "renewed the painting hanging on the northern wall".[9] Modern scholarship has convincingly identified Jacob Heinrich Elbfas (1600–1664), guild master from 1628 and court painter of Queen Maria Eleonora from 1634, as the artist responsible.[10] Based on the brief note referencing the painting's "renewal" in 1636, it was long assumed that the extant painting was in fact the original from 1535, and that the work performed on it in the 17th century was little more than restoration of some kind. However, when the painting was taken down in mid-October 1998 to allow a group of experts from various fields to restore and document it, this notion had to be completely reassessed. A dendrochronological investigation showed that the wood used for the panel came from trees cut down in the early 17th century: the painting in question must therefore be a copy and not the restored original.[11]

Notwithstanding the excellent state of the wooden panel prior to its 1998 restoration, the painting was unevenly covered with layers of dust and yellowed varnish. This was particularly pronounced in the area of the sky, obscuring many fine details and altering this area's colouring. Once these layers were removed, it was discovered that the original grey-blue sky had been repainted with broad strokes of a deep blue dye mixed with a fixing agent. An analysis of the blue pigments in the painting showed that the original blue colour, still discernible as a bright line above the horizon, was composed of azurite, while the blue pigment in more superficial layers was true ultramarine or lapis lazuli. The ultramarine layer has been identified as prussian blue, a pigment which was favoured from the early 18th century onwards. Additional alteration of the painting is well attested in parish accounts; the painting was "varnished and somewhat restored" by the painter Aline Bernard (1841–1910) in 1885, and a second time in 1907 by a Nils Janzon. The latter restoration was probably limited to the addition of a thick layer of varnish.[10]

When the painting was thus copied in the 17th century from the 16th-century original, the painting was furnished with a Baroque frame carrying a heart-shaped cartouche. This cartouche displayed the message:

The twentieth day in the month of April was seen in the sky over Stockholm such signs from almost seven to nine in the forenoon"

in Latin, repeated in Swedish and German. In 1885, the frame was repainted in brown by Leonard Lindh, who also modernized the Swedish and German texts and added his signature at the lower right. During the 1907 restoration the frame was repainted yet again, only to be repainted in its original colour twenty years later, at which time the original text was also uncovered.[12]

History

Background

In 1523, as the newly elected King of Sweden,[13] Gustav Vasa had to unify a kingdom which, unlike a modern nation-state, was composed of separate provinces not necessarily happy with his reign. He also had to prepare for a potential Danish attack, and resist the influence of German states and merchants with an interest in reintroducing the hegemony of the Hanseatic League over the Baltic lands.[14] Facing these challenges, the king saw conspiracies everywhere — sometimes correctly — and started to thoroughly fortify his capital while purging it of potential enemies.[15]

Shortly after his coronation, Gustav Vasa heard of the reformatory sermons delivered by Olaus Petri in Strängnäs and called him to Stockholm to have him appointed councillor in 1524. When Petri announced his marriage the following year, the solemnity of the celebration infuriated Catholic prelates to the extent Petri was excommunicated, while the king, in contrast, gave his unreserved support. Although the king and the reformer collaborated initially, they started to pull in different directions within a few years.[16] As the king carried out the Reformation from 1527, Catholic churches and monasteries were demolished or used for other purposes. Petri strongly opposed the king's methods of depriving the church of its assets and in his sermons he began to criticize the king's actions.[2] While both the king and Petri were thus devoted to both establishing what was to become the Swedish state and the new religious doctrine, they were also involved in domestic struggle for power,[17] a situation fuelled by various enemies and Counter Reformation propaganda.

Events

The primary historical source describing the events following the celestial phenomenon is the minutes of the proceedings from the king's legal process against the reformers Olaus Petri and Laurentius Andreae in 1539–1540. The process was originally described in the chronicle of Gustav Vasa written by the clerk and historian Erik Jöransson Tegel in the early 17th century.[17]

Sun dogs were apparently well known during the Middle Ages, as they are mentioned in the Old Farmer's Almanac (Bondepraktikan) which states that the phenomenon forecasts strong winds, and also rain if the sun dogs are more pale than red.[18] According to the passage in the Vasa Chronicle, however, both Petri and the master of the mint Anders Hansson were sincerely troubled by the appearance of these sun dogs. Petri interpreted the signs over Stockholm as a warning from God and had the Vädersolstavlan painting produced and hung in front of his congregation. Notwithstanding this devotion, he was far from certain on how to interpret these signs and in a sermon delivered in late summer 1535, he explained there are two kinds of omens: one produced by the Devil to allure mankind away from God, and another produced by God to attract mankind away from the Devil — one being hopelessly difficult to tell from the other. He therefore saw it as his duty to warn both his congregation, mostly composed of German burghers united by their conspiracy against the king, and the king himself.[15]

However, on his return to Stockholm in 1535, the king had prominent Germans imprisoned and accused Petri of replacing the law with his own "act of faith". In response, Petri warned his followers that the lords and princes interpreted his sermons as rebellious and complained about the ease with which punishment and subversion were carried through, while restoring "what rightly and true is" was much harder. In a sermon published in 1539, Petri criticized the misuse of the name of God "now commonly established", a message clearly addressed to the king. Petri also explained to his congregation that the Devil ruled the world more obviously than ever, that God would punish the authorities and those who obeyed them, and that the world had become so wicked that it was irrevocably doomed.[15]

The king's interpretation of the phenomenon, however, was that no significant change was presaged, as the "six or eight sun dogs on a circle around the true sun, have apparently disappeared, and the true natural sun has remained itself".[19] He then concluded that nothing was "much different, since the unchristian treason that Anders Hansson and several of that party had brought against His Highness, was not long thereafter unveiled".[20] The king referred to the so-called "Gun Powder Conspiracy" uncovered in 1536, which aimed at murdering him by a blasting charge hidden under his chair in the church. This resulted in various death sentences and expatriations, including Mint Master Anders Hansson who was accused of being a counterfeiter.[21]

Petri further excited royal disapproval by writing a chronicle describing contemporary events from a neutral point of view.[22] Both Olaus Petri and Anders Hansson were eventually sentenced to death as a result of the trial in 1539/1540, but were later reprieved.[2] In the end, the king achieved his aim and the appointment of bishops and other representatives of the church was placed under his jurisdiction. [21]

Censorship

When Tegel's Vasa Chronicle was published in 1622, the section describing the king's legal process and death sentences against the reformers was regarded as unfavourable to the Vasa dynasty and was subsequently left out. The original manuscript, finally published in 1909, was however not the only account of the events. The oldest report, dating from the 1590s, is a handwritten manuscript simply confirming the event, and a publication on meteorological phenomena published in 1608 described the halo in 1535 as "five suns surrounding the right one with its rings as still depicted in the painting hanging in the Great Church[23]".[24]

Knowledge of the events faded: in 1622 when the Danish diplomat Peder Galt asked for the meaning of the signs in the painting, he could get no replies anywhere in the city. He translated the Swedish text then accompanying the painting to Latin — "Anno 1535 1 Aprilis hoc ordine sex cœlo soles in circulo visi Holmie a septima matutina usque ad mediam nonam antermeridianam" — and concluded that the real sun represented Gustav Vasa and the other suns his successors, an assumption he thought confirmed by contemporary Swedish history. Even this confused report was soon forgotten and in 1632 the halo display in the painting was described in a German leaflet as three beautiful rainbows, a ball, and an eel hanging in the sky over the Swedish capital day and night for four weeks in 1520, furthermore interpreted as a prophecy announcing the forthcoming liberation of Protestant Germany by "the Lion from the North" (i.e. King Gustavus Adolphus).[25]

With the publishing of the first Swedish ecclesiastical history in 1642, the interpretation of the painting and the historical details surrounding it found a new path to follow. Relying on a publication from 1620, the sun dogs are said to have appeared first to King John III (1537–1592) on his deathbed – the painting subsequently being produced by the papist-friendly king in order to save the souls of the Protestant kingdom – and a second time before King Gustavus Adolphus shortly before his death at the Battle of Lützen in 1632.[26]

The 1592 date remained the established one until the 19th century. In the 1870s, however, several publications corrected the dating and within a few decades 1535 became the generally accepted date. The painting's correct historical context was finally laid bare with the publication of the censored manuscript from the Vasa Chronicle in 1909.[27]

Historic icon

Over time, the painting has become emblematic of the history of Stockholm, and as such appears frequently in various contexts. The 1000 kronor banknote published in 1989 shows a portrait of King Gustav Vasa, based on a painting from the 1620s, in front of details from Vädersolstavlan. In the arcs of the parhelion is the microtext SCRIPTURAM IN PROPRIA HABEANT LINGUA, which roughly translates to "Let them have the Holy Scripture in their own language". This is a quote from a letter written by the king in which he ordered a translation of the Bible into the Swedish language.[28]

Two stamps engraved by Lars Sjööblom were published in March 2002 for the 750th anniversary of Stockholm. They were both printed in two colours, an inland postage depicts the entire old town, while the 10 kronor stamp focuses on the castle and the church.[29][30]

For the restoration of the Gamla stan metro station in 1998 the artist Göran Dahl furnished the walls and floors with motifs from various medieval textiles and manuscripts, including the Överhogdal tapestries and the 14th-century Nobilis humilis (Magnushymnen) from the Orkney Islands. Vädersolstavlan is prominently featured on the eastern wall just south of the platform where the terrazzo wall depicts the emblematic sun dog arcs interwoven with enlarged fragments of textiles.[31]

The painting is used on a variety of merchandise — such as puzzles,[32] posters, notebooks[33] — in museum shops and other cultural institutions in Stockholm, like the Museum of Medieval Stockholm and the Stockholm City Museum.

Medieval Stockholm

Just as the 1630s replica has proven to be an accurate copy of the lost original,[34] the panorama has proven to be a surprisingly reliable historical document offering a rare and detailed glimpse of medieval Stockholm. The landscape and a great number of notable buildings are correctly rendered in such great detail, that historical censorship, misinterpretations, and later restorations have not prevented modern research from repeatedly corroborating the painting's accuracy.

In the painting, the medieval city is viewed looking east with the dark waters of Riddarfjärden in the foreground and the interior of the Stockholm archipelago in the background. Although the event depicted is said to have occurred in the morning, the city is painted in evening light.

Storkyrkan church and Tre Kronor castle

The painting is centred on the Storkyrkan church, first mentioned in historical records in 1279 and gradually enlarged over the following centuries. In 1468–1496, during the reign of Sten Sture the Elder, its size was doubled — the chapels were transformed into aisles, while rounded windows and a taller roof allowed more light into the building. The building in the painting depicts the church as it must have appeared when Gustav Vasa became king — the buttresses added in the 1550s are not present in the painting, which seem to confirm that the 17th century copy was faithful to the original.[34] The church still exists, although the present exterior is mostly a later Baroque design.

Immediately behind the church is Tre Kronor castle. Destroyed by fire in 1697 and subsequently replaced by the Stockholm Palace, it was named after the central citadel, a large gun tower emblazoned with the Three Crowns symbol, known as the first building in Stockholm and a symbol for the Swedish Crown. While it is not known when the symbol was first added to the citadel (it became the national coat of arms in the late 14th century), it was gilded during the 16th century.[35] Again, the painting is strictly accurate, as the 1540s enlargement of the tower is not present in the image. The castle's eastern wing, the king's personal residence, was destroyed by fire in 1525 and in letters ten years later the king, burdened by debts of war to Lübeck, expressed his indignation over the fact that the reconstruction was still not completed. In the painting to the right of the church the eastern wing is accurately depicted as under construction, the exposed roof trusses confirming the inconvenience experienced by the monarch.[36]

However, the two western towers left of the church display an unusual detail in the painting. The uniformly proportioned, large, square windows depicted there are associated with the Italian Renaissance, which was introduced in Sweden in 1572 during reconstruction of Kalmar Castle. While the construction works of Gustav Vasa are poorly documented, the presence of these windows in Stockholm in 1535 is unlikely. It seems more credible that this part of the painting had been damaged before 1632, forcing the copyist to rely on another source. As the two square and crenellated towers in the painting are depicted much as they appear on a copperplate of Stockholm produced by Frantz Hogenberg around 1560–1570, the painting thus probably renders this part of the castle as it appeared while the reconstruction was still under way, before its completion in the 1580s.[37]

Riddarholmen

The islet in the left foreground, today known as Riddarholmen ("Knights' Islet"), was during the medieval era known as Gråmunkeholmen ("Greyfriars Islet") after the Franciscan monastery located there and in the painting represented as a building with stepped gables and a tall turret at the far side of the islet. Together with other similar institutions, the monastery was closed by the king following the Reformation although the building was used as a hospital until the mid 16th century. The turret of the monastery was replaced by the cast-iron spire of Riddarholm Church in the 19th century, but the remains of the monastery still exist inside the church and under the surrounding buildings.[38]

The two defensive towers appearing along the near shoreline of the islet are still present, their structures remain intact although their exteriors are considerably altered. The leftmost is Birger Jarls torn located in the north-western corner of the islet and erroneously named after Birger Jarl, by tradition attributed to be the founder of Stockholm. The other is the so-called Vasatornet ("Tower of Vasa"), today forming the southern tower of the Wrangel Palace. For the construction of the towers and other defensive structures, the king used bricks from the monastery Klara kloster located just north of the city but absent in the painting. Since the monastery is known to have been demolished immediately following the introduction of Protestantism in 1527, the painting is, again, a credible source rendering the city as it appeared in 1535.[39]

Riddarholmen seen from the City Hall (facing south-east) |  The Wrangel Palace and the Vasa Tower (right) |

Helgeandsholmen

Just behind the Greyfriars turret is the islet of Helgeandsholmen, where the northern city gate and defensive wall were located. Today occupied by the Swedish Parliament, this islet was named after the charitable institution, Helige andens holme ("Islet of the Holy Spirit"), located there from around 1300 and discernible in the painting as a building with stepped gables facing an open space perhaps indicating the location of the demolished Johannite monastery. King Gustav Vasa had all the charitable institutions in the city merged into a single one housed in the former Greyfriars monastery on Riddarholmen, so the monasteries in the painting were all the possession of the crown when the painting was produced.[39]

The painting shows a bridge stretching north (left) from the northern city gate to an open space. This is the site of perhaps the oldest river crossing in Stockholm, today replaced by the Norrbro, Riksbron, and Stallbron bridges. The latter of these (not present in the painting) is a 19th-century bridge still located on the site of the medieval structure. It connects Riksgatan passing through the Parliament Building on Helgeandsholmen to the square Mynttorget on Stadsholmen, from where Västerlånggatan extends it further south.[40][41]

To the left of the open space north of the medieval city are the steep southern slopes of the Brunkebergsåsen esker, a geological feature whose remains still stretch north through the city.[42] Missing in the painting is the small island of Strömsborg, which was little more than an insignificant cliff at the time.[43]

The northern city gate in front of the church and the palace in 1675. During the 16th century Helgeandsholmen was just a series of scattered cliffs and islets. |  Another detail showing Birger Jarls torn in front of Strömsborg |

Southern city gate

The two defensive towers of the southern city gate appearing in the left foreground, are known to be much older than the painting but their history remains poorly documented. The outer tower (Yttre Söderport) was built on an artificial island in the strait and was rebuilt in front of an expected attack by King Christian II of Denmark in the late 1520s. In Blodbadstavlan ("The Bloodbath Painting"), an image ten years older than Vädersolstavlan, it appears with a cone-shaped roof seriously damaged during the Danish assault. In Vädersolstavlan, the inner tower (Inre Söderport) is similar to the exterior tower, and both structures, together with the narrow bridge between them, match other historical sources. Additions younger than the 1530s, such as the reinforcements ordered by Gustav Vasa during the 1540s, are missing in the painting but present in engravings from 1560 to 1580, which confirms Vädersolstavlan is a credible contemporary document.[44]

Where the southern city gates were, is today the Slussen area. The sluice and the locks of Karl Johanslussen had to be rebuilt regularly, and the appearance of the city's southern approach changed constantly. In the early 1930s, when a multi-story concrete roundabout replaced everything else in the area, the foundations of the outer defensive tower were discovered[45] (known as Gustav Vasas rondell) and remains of the southern defensive structures can still be found below the present squares in the area.[46]

Detail from an engraving showing the area in the 1560s. Note the wall between the towers added in the 1540s and absent in the painting. |  The Slussen area in 1865 looking north-west. The entire area was completely rebuilt in the early 1930s. |

Defensive structures

Along the western shoreline are several defensive structures of various ages. The wooden defence structure built along the shore around 1650 is absent in the painting, but the double row of piles protecting the western harbour is present. It served both as a defensive structure and, because a duty was imposed on all incoming ships, as an important source of income for the city. The western defence structures were neglected around 1500, which resulted in settlements being constructed between the western city wall and a shoreline constantly pushed westward by landfill, just as the painting renders it.[47]

While the old city wall is not discernible in the painting, several of the towers sitting on the city gates are (left to right):[47]

- The tower with a cone-shaped roof just to the right of the Greyfriars monastery was called Draktornet ("Dragon's Tower"), and in 1535 served as a prison.

- Just to the right of it was Gråmunketornet ("Greyfriars Tower") with stepped gables and a large gate leading to Riddarholmen island. Excavations in the 1950 showed that the gate was 1.5 metres (5 feet) wide.

- The second tower with stepped gables but without a gate was the Lejontornet ("Lion's Tower"), the foundations of which were rediscovered during an archaeological excavation in 1984 and are now part of the interior of a restaurant on Yxsmedsgränd.

- Between Lejontornet and the southern city gate flanked by two boats is a wooden structure, roughly triangular in plan; this is a defensive tower called Kivenäbben, built in 1520–1523 on piles in the water.

Lastly, next to the southern city gate is an open space, believed to be the precursor of present-day Kornhamnstorg, the square where ships from the Lake Mälaren region used to deliver corn and iron.[48]

Other buildings and surrounding ridges

The turret on the right side of the church and the palace was the Blackfriars monastery, inaugurated in 1343 and demolished in 1547. It was built on the location of the first southern defensive tower, of which no traces have been found. The basement of the monastery, however, can still be seen by Benickebrinken and the school next to Tyska Stallplan.[38]

During the Middle Ages, there were two harbours west and east of the city's southern square; in the painting they are only suggested by the presence of a mast behind the city. On the western shore at Kornhamn ("Grain Harbour") – today Kornhamnstorg – grain, iron, and other goods from the Lake Mälaren area were delivered. These goods were then weighed in the Våghuset ("The Scales Building", i.e. a weigh house), another important source of income for both the crown and the city, before being transported to the eastern harbour, Kogghamnen ("The Cog Harbour") – today the southern part of Skeppsbron – from which large ships delivered goods across the Baltic Sea.[49]

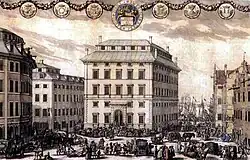

In the painting, the Våghuset is the building with stepped gables and iron bars to the right of the Blackfriars monastery facing Järntorget ("Iron Square"). Våghuset was located where the Södra Bankohuset ("Southern [National] Bank Building") is today. Just behind Våghuset there is another stepped gable symbolizing the Klädeshuset ("Broadcloth Building") where goods were stored. The building with stepped gables between the church and the Blackfriars monastery was Själagården ("Soul's Homestead").[50] It was built in the 15th century at Själagårdsgatan to accommodate the poor and aged but also priests and others serving at the church. During the reign of Gustav Vasa it was transformed into the first royal printing house.[49]

Vädersolstavlan |

Aerial view of Lilla Värtan |

|

Left: Detail of the left background. Östermalm and Northern Djurgården is located in front of the strait Lilla Värtan with Lidingö behind.

| |

Between the city and the horizon are several rural islands, which today form part of central Stockholm. Behind the church and the castle is Skeppsholmen, which for centuries served as a base for the Swedish Navy together with Kastellholmen islet, which can be seen above the Blackfriars monastery. To the left of Skeppsholmen are two small islets, which are today merged into the peninsula of Blasieholmen. Behind these islands are Djurgården (right), Östermalm, and Norra Djurgården (left). On the horizon, the Lilla Värtan strait passes in front of Lidingö and, arguably, the interior islands of the Stockholm archipelago.[2]

Like the islands, the ridges surrounding the city, including the cliffs in the foreground, look very much as they still do. South (right) of the city is the island of Södermalm, where a cluster of buildings (see image of the southern city gate above) lined up along the shore called Tranbodarna were used to burn train oil (e.g. seal lard). The round building on the eastern end of Södermalm was the gallows hill. As depicted in the painting, it was used exclusively for men (women were beheaded). The gallows remained there until the late 17th century when they were moved to present-day Hammarbyhöjden south of the historical city centre.[48]

Halo display

A halo display featuring several distinct phenomena possibly present in the painting: Two sun dogs (bright spots), a parhelic circle (horizontal line), a 22° halo (circle), and an upper tangent arc. Cindy McFee, NOAA, December 1980. |

While the painting is arguably the oldest realistic depiction of a halo phenomenon — almost a century older than Christoph Scheiner's famous observation of a halo display over Rome in 1630[51] — the phenomenon was apparently not entirely understood. The image contains several obvious misinterpretations and a few peculiarities. Most notably, like many other early depictions of haloes,[52] the painting depicts a series of events occurring over several hours and is consistent in its preference for perfect circles rather than ellipses.

A work of art produced in the spirit of the Danube School[53] (see Possible prototypes above), Vädersolstavlan features realistic depictions of cirrus clouds and the sky is properly rendered, going from bright blue near the horizon to dark blue near zenith. The shadows in the lower half of the painting, however, seem to suggest the Sun is located in the west — even leaving the southern façades in shadow — which is incorrect as historical sources claim the event lasted from 7 to 9 a.m.[54] In contrast to the city below it, the halo phenomenon is depicted vertically in a fisheye perspective with the major circle centred on zenith (like in the ray tracing solution above).[55]

In the painting, the actual Sun is the yellow ball in the upper-right corner surrounded by the second circle. The large circle taking up most of the sky is a parhelic circle, parallel to the horizon and located at the same altitude as the Sun, as the painting renders it. This is actually a common halo, although a full circle as depicted is rare. Such parhelic circles are caused by horizontally oriented plate ice crystals reflecting sun rays. In order for a full circle to appear sun rays must be reflected both internally and externally.[56][57] The circle surrounding the Sun is a 22° halo, as the name implies located 22° from the Sun. While the painting depict it pretty much as it normally appears, it should be centred on the Sun and is misplaced in the painting.[58] The pair of arcs flanking the 22° halo and crossing each other are most likely a misinterpretation of a circumscribed halo. While the Sun is still low, it starts as a V-shaped upper tangent arc which gradually develops into something looking like the unfolding wings of a seagull. As the Sun ascends, in rare cases it finally joins with the lower tangent arc to form an ellipse which closes in on the circumscribed 22° halo.[59]

The sun dogs or parhelia, in the painting erroneously pinned to the misinterpreted arcs of the circumscribed halo, are rather frequent optical phenomena which appear when sunlight is refracted by hexagonal ice crystals forming cirrus or cirrostratus clouds. When the Sun is still low, they are located on the 22° halo, the way they are most commonly observed, and as the Sun ascends they move laterally away from the 22° halo.[60] At rare occasions, they can actually reach the circumscribed halo. As depicted in the painting, the sun dogs are located midway between the 22° halo and the circumscribed halo, and, assuming they are correctly rendered, the Sun should have been located at about 35–40° above the horizon (as in the simulation above).[61][62]

The unintelligible arc on the lower right might be a misinterpreted and misplaced infralateral arc missing its mirrored twin. These phenomena are, however, rare and only form when the Sun is below 32°. Their shape change quickly as the Sun rises, and as the painting most likely isn't depicting any specific moment, it is impossible to draw any conclusions from the mysterious shape in the painting.[63]

The crescent moon shape in the middle of the sky looks very much like a circumzenithal arc, which is parallel to the horizon but centred at and located near zenith. However, they only form when the Sun is located lower than 32.2° and are at their brightest when the Sun is located at 22°, which is not consistent with other haloes depicted in the painting. Furthermore, one of the most striking features of circumzenithal arcs is their rainbow colours, and the shape in the painting is perfectly devoid of any colours. It is however not a complete circle (see Kern arc), and it is facing the Sun, which are both correct properties for this phenomenon.[64]

The white spot on the lower left part of the parhelic circle, opposite to the Sun, should be an anthelion, a bright halo always located at the antisolar point. Most scientists are convinced anthelia are caused by the convergence of several halo arcs (of which are no traces in the painting) and thus should not be regarded as an independent halo. Other researchers believe column-shaped crystals could generate the phenomenon which could explain the constellation in the painting.[65]

Finally, the minor, slightly bluish dots, flanking the anthelion, may be perfectly depicted 120° parhelia. These halos are produced by the same horizontally oriented ice crystals that produce sun dogs and the parhelic circle. They result from multiple interior reflections of sun rays entering the hexagonal top face and leaving through the bottom face.[66]

See also

References

Citations

- "Vädersolstavlan". Sveriges Television. 10 July 2003. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, Vädersolstavlan i Storkyrkan, historisk bakgrund

- Rothlind, p 7

- Rothlind, pp 12–13

- Rothlind, p 10

- Hermelin, pp 48–49

- Svanberg, pp 70–72

- Svanberg, pp 66–67

- Dänn 15. October betallt M. Jacob Conterfeyer att hann hafuer förnyat denn taffla huar upå ståår thet himmelsteckn som syntes för hundrade Åhr sedann här i Stockhollm och står på Nårre murenn (Rothlind, p 8)

- Rothlind, p 8

- Rothlind, p 13

- Rothlind, pp 13–14

- "Personakt för Gustav Vasa (Eriksson)" (in Swedish). historiska-personer.nu. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- Hermelin, p 46

- Hermelin, pp 43–45

- Höijer, Olaus Petri och Gustav Vasa

- Hermelin, p 42

- Gunnarson, Fredrik (2006). "Tidsuppfattningen i det förmoderna Sverige" (PDF). Uppsala: University of Uppsala. p. 68. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- icke så platt för skämptt, att thett iw skulle nogett betecknedh hafue, efterty thett syntess sex eller otte wäder soler uti en kreetz kringh om then rette sool, the doch alla synnerligen förginges, och then rette naturlige sool blef doch widh sigh. (Hermelin, pp 45–46)

- myckett olijkitt, efter thett okristellige landzförrädherij som Anders Hansson och flere of thett partij emot Hans Kon. M:tt förhänder hade, bleff icke longt ther efter uppenbartt ... (Hermelin, pp 45–46)

- Hermelin, pp 45–46

- Rosell, Olaus Petri

- Anno 1535, 1 Aprilis ifrå 7. til 9. om morghonen, såges här i Stockholm 5. Solar omkring den rätte, medh sine Ringar, såsom the än idagh här i Stockholms store Kyrkia på een Tafla stå afmålade. (Hermelin, pp 53–54)

- Hermelin, pp 53–54

- Hermelin, pp 54–55

- Hermelin, p 58

- Hermelin, pp 60–62

- "1000-kronorssedel". National Bank of Sweden. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- "Vädersolstavlan (2002 inland stamp)". Postmuseum. Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- "Stadsholmen (2002 10 kr stamp)". Postmuseum. Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- "Gamla stan". AB Storstockholms Lokaltrafik. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- "Merchandise at Stockholm City Museum". Stockholm City Museum. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- "On-line shop at Museum of Medieval Stockholm" (in Swedish). Museum of Medieval Stockholm. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, St Eriks årsbok 1999, p 36

- Lindgren, Varifrån härstammar Tre Kronor-symbolen?, p 17

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, St Eriks årsbok 1999, p 25

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, St Eriks årsbok 1999, pp 23–24

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, St Eriks årsbok 1999, pp 27–28

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, St Eriks årsbok 1999, pp 32–33

- "Gamla stan". Stockholms gatunamn (2nd ed.). Stockholm: Kommittén för Stockholmsforskning. 1992. pp. 70–71. ISBN 91-7031-042-4.

- Dufwa, Arne (1985). "Broar och viadukter: Stallbron". Stockholms tekniska historia: Trafik, broar, tunnelbanor, gator (1st ed.). Uppsala: Stockholms gatukontor and Kommittén för Stockholmsforskning. p. 184. ISBN 91-38-08725-1.

- Glase, Béatrice; Glase, Gösta (1988). "Inre Stadsholmen". Gamla stan med Slottet och Riddarholmen (in Swedish) (3rd ed.). Stockholm: Bokförlaget Trevi. p. 36. ISBN 91-7160-823-0.

- Lönnqvist, St Eriks årsbok 1994, pp 157–168

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, St Eriks årsbok 1999, pp 33–34

- Lorentzi, Mari; Olgarsson, Per (2005). Slussen – 1935 års anläggning (PDF) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Stockholm City Museum. p. 28. ISBN 91-85233-37-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- Söderlund, St Eriks årsbok 2004, pp 11–21

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, St Eriks årsbok 1999, pp 34–36

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, St Eriks årsbok 1999, pp 31–32

- Lindgren, Burspråk, Kåken, Sankt Göran och draken, p 25

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, St Eriks årsbok 1999, pp 29–30

- Malmquist, pp 31–41

- Cowley, Les. "The 1790 St Petersburg Display". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- Svanberg, p 86

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, St Eriks årsbok 1999, p 20

- Svanberg, p 65

- Cowley, Les. "Parhelic circle". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- Cowley, Les. "Parhlic Circle Formation". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- Cowley, Les. "22° Circular Halo". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- Cowley, Les. "Tangent Arcs". atopics.co.uk. Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- Cowley, Les. "Circumscribed Halo – 43° high sun". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- Keith C. Heidorn. "Sun Dogs". The Weather Doctor. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- Cowley, Les. "Sundogs – parhelia – mock suns". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- Cowley, Les. "Supralateral & Infralateral arcs". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- Cowley, Les. "Circumzenithal Arc". atoptics.co.uk. Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- "Anthelion". Arbeitskreis Meteore e. V. Retrieved 22 April 2007. (A photo of an anthelion and anthelic arcs.)

- Cowley, Les. "120° Parhelia". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

Sources

- St Eriks årsbok (in Swedish), Samfundet S:t Erik, Stockholm

- 1994, Yppighet och armod i 1700-talets Stockholm, ISBN 91-972165-0-X.

- Lönnqvist, Olov. De låga stenhällarna som blev Strömsborg. pp. 157–168.

- 1999, Under Stockholms himmel, ISBN 91-972165-3-4.

- Rothlind, John. Vädersolstavlan i Storkyrkan – I Konservering och teknisk analys. pp. 7–15.

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, Margareta. Vädersolstavlan i Storkyrkan – II Analys av stadsbild och bebyggelse. pp. 19–40.

- Hermelin, Andrea. Vädersolstavlan i Storkyrkan – III En målning i reformationens tjänst – Historik enligt skriftliga källor. pp. 41–64.

- Svanberg, Jan. Vädersolstavlan i Storkyrkan – IV Det konsthistoriska sammanhanget. pp. 65–86.

- 2004, Slussen vid Söderström, ISBN 91-85267-21-X.

- Söderlund, Kerstin. Stockholm heter det som sprack av – Söderström i äldsta tid. pp. 11–21.

- 2007, Stockholm Huvudstaden, ISBN 978-91-85801-11-4.

- Malmquist, Harriet. Vädersolstavlan och halofenomenen. pp. 31–41.

- 1994, Yppighet och armod i 1700-talets Stockholm, ISBN 91-972165-0-X.

- Gamla stan under 750 år (in Swedish) (1st ed.). Stockholm: B. Wahlströms. 2002. pp. (CD-ROM/DVD). ISBN 91-85100-64-1.

- Weidhagen-Hallerdt, Margareta. Vädersoltavlan i Storkyrkan, historisk bakgrund.

- Höijer, Pia. Olaus Petri och Gustav Vasa.

- Rosell, Carl Magnus. Olaus Petri.

- Lindgren, Rune (1992). Gamla stan förr och nu (in Swedish). Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. ISBN 91-29-61671-9.

_2.jpg.webp)