Trojan Horse

The Trojan Horse was a wooden horse said to have been used by the Greeks during the Trojan War to enter the city of Troy and win the war. The Trojan Horse is not mentioned in Homer's Iliad, with the poem ending before the war is concluded, and it is only briefly mentioned in the Odyssey. But in the Aeneid by Virgil, after a fruitless 10-year siege, the Greeks constructed a huge wooden horse at the behest of Odysseus, and hid a select force of men inside, including Odysseus himself. The Greeks pretended to sail away, and the Trojans pulled the horse into their city as a victory trophy. That night, the Greek force crept out of the horse and opened the gates for the rest of the Greek army, which had sailed back under the cover of darkness. The Greeks entered and destroyed the city, ending the war.

| Trojan War |

|---|

|

Metaphorically, a "Trojan horse" has come to mean any trick or stratagem that causes a target to invite a foe into a securely protected bastion or place. A malicious computer program that tricks users into willingly running it is also called a "Trojan horse" or simply a "Trojan".

The main ancient source for the story still extant is the Aeneid of Virgil, a Latin epic poem from the time of Augustus. The story featured heavily in the Little Iliad and the Sack of Troy, both part of the Epic Cycle, but these have only survived in fragments and epitomes. As Odysseus was the chief architect of the Trojan Horse, it is also referred to in Homer's Odyssey.[1] In the Greek tradition, the horse is called the "wooden horse" (δουράτεος ἵππος douráteos híppos in Homeric/Ionic Greek (Odyssey 8.512); δούρειος ἵππος, doúreios híppos in Attic Greek).

Warriors in the horse

Thirty of the Achaeans' best warriors hid in the Trojan horse's womb and two spies in its mouth. Other sources give different numbers: The Bibliotheca 50;[2] Tzetzes 23;[3] and Quintus Smyrnaeus gives the names of 30, but says there were more.[4] In late tradition the number was standardized at 40. Their names follow:

| Names | Sources | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintus | Hyginus | Tryphiodorus | Tzetzes | |

| Odysseus (leader) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Acamas | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Agapenor | ✓ | |||

| Ajax the Lesser | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Amphidamas | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Amphimachus | ✓ | |||

| Anticlus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Antimachus | ✓ | |||

| Antiphates | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Calchas | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Cyanippus | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Demophon | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Diomedes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Echion | ||||

| Epeius | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Eumelus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Euryalus | ✓ | |||

| Eurydamas | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Eurymachus | ✓ | |||

| Eurypylus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Ialmenus | ✓ | |||

| Idomeneus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Iphidamas | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Leonteus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Machaon | ✓ | |||

| Meges | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Menelaus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Menestheus | ✓ | |||

| Meriones | ✓ | |||

| Neoptolemus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Peneleos | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Philoctetes | ✓ | |||

| Podalirius | ✓ | |||

| Polypoetes | ✓ | |||

| Sthenelus | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Teucer | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Thalpius | ✓ | |||

| Thersander | ✓ | |||

| Thoas | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Thrasymedes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Number | 30 | 9 | 23 | 23 |

Literary accounts

According to Quintus Smyrnaeus, Odysseus thought of building a great wooden horse (the horse being the emblem of Troy), hiding an elite force inside, and fooling the Trojans into wheeling the horse into the city as a trophy. Under the leadership of Epeius, the Greeks built the wooden horse in three days. Odysseus's plan called for one man to remain outside the horse; he would act as though the Greeks had abandoned him, leaving the horse as a gift for the Trojans. An inscription was engraved on the horse reading: "For their return home, the Greeks dedicate this offering to Athena". Then they burned their tents and left to Tenedos by night. Greek soldier Sinon was "abandoned" and was to signal to the Greeks by lighting a beacon.[5]

In Virgil's poem, Sinon, the only volunteer for the role, successfully convinces the Trojans that he has been left behind and that the Greeks are gone. Sinon tells the Trojans that the Horse is an offering to the goddess Athena, meant to atone for the previous desecration of her temple at Troy by the Greeks and ensure a safe journey home for the Greek fleet. Sinon tells the Trojans that the Horse was built to be too large for them to take it into their city and gain the favor of Athena for themselves.

While questioning Sinon, the Trojan priest Laocoön guesses the plot and warns the Trojans, in Virgil's famous line Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes ("I fear Greeks, even those bearing gifts"),[6] Danai (acc Danaos) or Danaans (Homer's name for the Greeks) being the ones who had built the Trojan Horse. However, the god Poseidon sends two sea serpents to strangle him and his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus before any Trojan heeds his warning. According to Apollodorus the two serpents were sent by Apollo, whom Laocoön had insulted by sleeping with his wife in front of the "divine image".[7] In the Odyssey, Homer says that Helen of Troy also guesses the plot and tries to trick and uncover the Greek soldiers inside the horse by imitating the voices of their wives, and Anticlus attempts to answer, but Odysseus shuts his mouth with his hand.[8] King Priam's daughter Cassandra, the soothsayer of Troy, insists that the horse will be the downfall of the city and its royal family. She too is ignored, hence their doom and loss of the war.[9]

This incident is mentioned in the Odyssey:

What a thing was this, too, which that mighty man wrought and endured in the carven horse, wherein all we chiefs of the Argives were sitting, bearing to the Trojans death and fate![10]

But come now, change thy theme, and sing of the building of the horse of wood, which Epeius made with Athena's help, the horse which once Odysseus led up into the citadel as a thing of guile, when he had filled it with the men who sacked Ilios.[11]

The most detailed and most familiar version is in Virgil's Aeneid, Book II[12] (trans. A. S. Kline).

After many years have slipped by, the leaders of the Greeks,

opposed by the Fates, and damaged by the war,

build a horse of mountainous size, through Pallas's divine art,

and weave planks of fir over its ribs

they pretend it's a votive offering: this rumour spreads.

They secretly hide a picked body of men, chosen by lot,

there, in the dark body, filling the belly and the huge

cavernous insides with armed warriors.

[...]

Then Laocoön rushes down eagerly from the heights

of the citadel, to confront them all, a large crowd with him,

and shouts from far off: "O unhappy citizens, what madness?

Do you think the enemy's sailed away? Or do you think

any Greek gift's free of treachery? Is that Ulysses's reputation?

Either there are Greeks in hiding, concealed by the wood,

or it's been built as a machine to use against our walls,

or spy on our homes, or fall on the city from above,

or it hides some other trick: Trojans, don't trust this horse.

Whatever it is, I'm afraid of Greeks even those bearing gifts."

Book II includes Laocoön saying: "Equo ne credite, Teucri. Quidquid id est, timeo Danaos et dona ferentes." ("Do not trust the horse, Trojans! Whatever it is, I fear the Danaans [Greeks], even those bearing gifts.")

Well before Virgil, the story is also alluded to in Greek classical literature. In Euripides' play Trojan Women, written in 415 BC, the god Poseidon proclaims: "For, from his home beneath Parnassus, Phocian Epeus, aided by the craft of Pallas, framed a horse to bear within its womb an armed host, and sent it within the battlements, fraught with death; whence in days to come men shall tell of 'the wooden horse,' with its hidden load of warriors."[13]

Factual explanations

It has been speculated that the story of the Trojan Horse resulted from later poets creatively misunderstanding an actual historical use of a siege engine at Troy. Animal names are often used for military machinery, as with the Roman onager and various Bronze Age Assyrian siege engines which were often covered with dampened horse hides to protect against flaming arrows.[14] Pausanias, who lived in the 2nd century AD, wrote in his book Description of Greece, "That the work of Epeius was a contrivance to make a breach in the Trojan wall is known to everybody who does not attribute utter silliness to the Phrygians";[15] by the Phrygians, he meant the Trojans.

Some authors have suggested that the gift might also have been a ship, with warriors hidden inside.[16] It has been noted that the terms used to put men in the horse are those used by ancient Greek authors to describe the embarkation of men on a ship and that there are analogies between the building of ships by Paris at the beginning of the Trojan saga and the building of the horse at the end;[17] ships are called "sea-horses" once in the Odyssey.[18] This view has recently gained support from naval archaeology:[19][20] ancient text and images show that a Phoenician merchant ship type decorated with a horse head, called hippos ('horse') by Greeks, became very diffuse in the Levant area around the beginning of the 1st millennium BC and was used to trade precious metals and sometimes to pay tribute after the end of a war.[20] That has caused the suggestion that the original story viewed the Greek soldiers hiding inside the hull of such a vessel, possibly disguised as a tribute, and that the term was later misunderstood in the oral transmission of the story, the origin to the Trojan horse myth.

Ships with a horsehead decoration, perhaps cult ships, are also represented in artifacts of the Minoan/Mycenaean era;[21][22] the image[23] on a seal found in the palace of Knossos, dated around 1200 BC, which depicts a ship with oarsmen and a superimposed horse figure, originally interpreted as a representation of horse transport by sea,[24] may in fact be related to this kind of vessels, and even be considered as the first (pre-literary) representation of the Trojan Horse episode.[25]

A more speculative theory, originally proposed by Fritz Schachermeyr, is that the Trojan Horse is a metaphor for a destructive earthquake that damaged the walls of Troy and allowed the Greeks inside.[26] In his theory, the horse represents Poseidon, who as well as being god of the sea was also god of horses and earthquakes. The theory is supported by the fact that archaeological digs have found that Troy VI was heavily damaged in an earthquake[26] but is hard to square with the mythological claim that Poseidon himself built the walls of Troy in the first place.[27]

Modern metaphorical use

The term "Trojan horse" is used metaphorically to mean any trick or strategy that causes a target to invite a foe into a securely protected place; or to deceive by appearance, hiding malevolent intent in an outwardly benign exterior; to subvert from within using deceptive means.[28][29][30]

Artistic representations

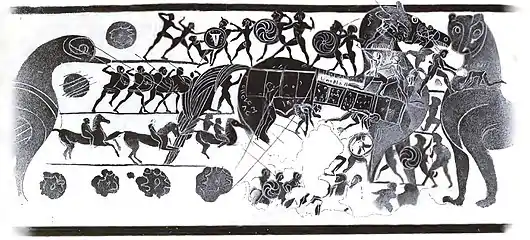

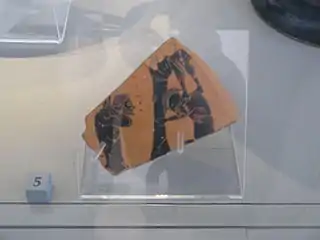

Pictorial representations of the Trojan Horse earlier than, or contemporary to, the first literary appearances of the episode can help clarify what was the meaning of the story as perceived by its contemporary audience. There are few ancient (before 480 BC) depictions of the Trojan Horse surviving.[31][32] The earliest is on a Boeotian fibula dating from about 700 BC.[33][34] Other early depictions are found on two relief pithoi from the Greek islands Mykonos and Tinos, both generally dated between 675 and 650 BC. The one from Mykonos (see figure) is known as the Mykonos vase.[31][35] Historian Michael Wood dates the Mykonos vase to the eighth century BC, before the written accounts attributed by tradition to Homer, and posits this as evidence that the story of the Trojan Horse existed before those accounts were written.[36] Other archaic representations of the Trojan horse are found on a Corinthian aryballos dating back to 560 BC[31] (see figure), on a vase fragment to 540 BC (see figure), and on an Etruscan carnelian scarab.[37] An Attic red-figure fragment from a kalyx-krater dated to around 400 BC depicts the scene where the Greek are climbing down the Trojan Horse that it's represented by the wooden hatch door.[38]

Trojan horse as depicted in the Histoire des jouets (1902)

Trojan horse as depicted in the Histoire des jouets (1902).jpg.webp) Detail from The Procession of the Trojan Horse in Troy by Domenico Tiepolo (1773), inspired by Virgil's Aeneid

Detail from The Procession of the Trojan Horse in Troy by Domenico Tiepolo (1773), inspired by Virgil's Aeneid.jpg.webp) The Trojan horse that appeared in the 2004 film Troy, now on display in Çanakkale, Turkey

The Trojan horse that appeared in the 2004 film Troy, now on display in Çanakkale, Turkey

Citations

- Broeniman, Clifford (1996). "Demodocus, Odysseus, and the Trojan War in "Odyssey" 8". The Classical World. 90 (1): 3–13. doi:10.2307/4351895. JSTOR 4351895.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Epitome 5.14

- Tzetzes, Posthomerica 641–650

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, The Fall of Troy xii.314–335

- Bibliotheca, Epitome, e.5.15

- "Virgil:Aeneid II". Poetryintranslation.com. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca, Epitome,Epit. E.5.18

- Homer, Odyssey, 4. 274–289.

- Virgil. The Aeneid. Trans. Robert Fitzgerald. New York: Everyman's Library, 1992. Print.

- "Homer, The Odyssey, Scroll 4, line 21". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Homer, Odyssey, Book 8, line 469". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Virgil". poetryintranslation.com.

- "The Trojan Women, Euripides". Classics.mit.edu. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Michael Wood, in his book "In search of the Trojan war" ISBN 978-0-520-21599-3 (which was shown on BBC TV as a series)

- "Pausanias, Description of Greece 1, XXIII,8". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Fields, Nic (2004). Troy c. 1700–1250 BC. Spedaliere, Donato and Spedaliere, Sarah Sulemsohn (illustrators). Oxford: Osprey. pp. 51–52. ISBN 1841767034. OCLC 56321915.

- See pages 22–26 in The fall of Troy in early Greek poetry and art, Michael John Anderson, Oxford University Press, 1997

- de Arbulo Bayona, Joaquin Ruiz (2009). "LOS NAVEGANTES Y LO SAGRADO. EL BARCO DE TROYA. NUEVOS ARGUMENTOS PARA UNA EXPLICACION NAUTICA DEL CABALLO DE MADERA" (PDF). Arqueología Náutica Mediterránea, Monografies del CASC. Girona. 8: 535–551.

- Tiboni, Francesco. "The Dourateos Hippos from allegory to Archaeology: a Phoenician Ship to break the Wall." Archaeologia maritima mediterranea 13.13 (2016): 91–104

- Tiboni, Francesco (5 December 2017). "La marineria fenicia nel Mediterraneo nella prima Età del ferro: il tipo navale Hippos". In Morozzo della Rocca, Maria Carola; Tiboni, Francesco (eds.). Atti del 2° convegno nazionale. Cultura navale e marittima transire mare 22–23 settembre 2016 (in Italian). goWare. ISBN 9788867979042.

- Salimbeti, A. "The Greek Age of Bronze - Ships". Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- Wachsmann, Shelley (2008). Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. ISBN 978-1603440806.

- "Minoan transport vessel with figure of horse superimposed".

- Evans, Arthur (1935). The Palace of Minos: a comparative account of the successive stages of the early Cretan civilization as illustrated by the discoveries at Knossos. Vol. 4. p. 827.

- Chondros, Thomas G (2015). "The Trojan Horse reconstruction". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 90: 261–282. doi:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2015.03.015.

- Eric H. Cline (2013). The Trojan War: A Very Short Introduction. ISBN 978-0199333820.

- Stephen Kershaw (2010). A Brief Guide to Classical Civilization. ISBN 978-1849018005.

- "Trojan horse". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- "a Trojan horse". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- "Trojan horse". Merriam Webster. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- Sparkes, B. A. (1971). "The Trojan Horse in Classical Art1". Greece & Rome. 18 (1): 54–70. doi:10.1017/S001738350001768X. ISSN 1477-4550. S2CID 162853081.

- Sadurska, Anna (1986). "Equus Trojanus". Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. Zürich. 3, 1: 813–817.

- British Museum. Dept. of Greek and Roman Antiquities; Walters, Henry Beauchamp (1899). Catalogue of the bronzes, Greek, Roman, and Etruscan, in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, British Museum. Wellesley College Library. London, Printed by order of the Trustees. p. 374.

- "Bronze bow fibula (brooch) with a glimpse of the Trojan Horse with wheels under feet – Images for Mary Beard's Cultural Exchange – Front Row's Cultural Exchange – BBC Radio 4". BBC. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Caskey, Miriam Ervin (Winter 1976). "Notes on Relief Pithoi of the Tenian-Boiotian Group". American Journal of Archaeology. 80 (1): 19–41. doi:10.2307/502935. JSTOR 502935. S2CID 191406489.

- Wood, Michael (1985). In Search of the Trojan War. London: BBC books. pp. 80, 251. ISBN 978-0-563-20161-8.

- "Carnelian scarab | Etruscan, Populonia | Late Archaic | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Peixoto, Gabriel B. (2022). "The Depiction of Temples in Attic Red Figure: from mid-5th to mid-4th century BCE". doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.27930.31687.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)