Timeline of İzmir

Below is a sequence of some of the events that affected the history of the city of İzmir (historically also Smyrna).

Timeline

| Date | Occurrence |

|---|---|

| c. 6000–4000 BC | İzmir region's first Neolithic and mid-Chalcolithic settlements in Yeşilova Höyük and the adjacent Yassıtepe Höyük, within the boundaries of the present-day Bornova metropolitan district located in the middle of the plain that extends starting from the tip of the Gulf of İzmir, last for at least two millennia. |

| starting c. 3000 BC | First traces of settlement attested in the mound (höyük) called either as Tepekule or under the same name as its neighborhood (Bayraklı) along a small peninsula in the northeastern corner of Gulf of İzmir's end which will later become the location of Old Smyrna. |

A port city unravels since millennia in the outlying waters of the Gulf of İzmir as narrow as a strait in its end as seen here from Mount Yamanlar. Mount Yamanlar is also where a crater lake named Karagöl (meaning Black Lake in Turkish) and also called as "Lake Tantalus" is found.

A port city unravels since millennia in the outlying waters of the Gulf of İzmir as narrow as a strait in its end as seen here from Mount Yamanlar. Mount Yamanlar is also where a crater lake named Karagöl (meaning Black Lake in Turkish) and also called as "Lake Tantalus" is found. Mount Sipylus is famous for its "Weeping Rock", associated with Niobe, daughter of the semi-legendary local ruler Tantalus, the first recorded sovereign to have controlled the area of the Gulf of İzmir.

Mount Sipylus is famous for its "Weeping Rock", associated with Niobe, daughter of the semi-legendary local ruler Tantalus, the first recorded sovereign to have controlled the area of the Gulf of İzmir. The "Throne", conjecturally associated with Pelops" in Yarikkaya locality in Mount Sipylus, is an isolated stone bench or altar possibly carved to accommodate a stone or wooden statue.

The "Throne", conjecturally associated with Pelops" in Yarikkaya locality in Mount Sipylus, is an isolated stone bench or altar possibly carved to accommodate a stone or wooden statue. Karabel Luvian warrior monument carved in rock dated to the 13th century BC and at a distance of 30 km from İzmir, near Kemalpaşa, deciphered as having been dedicated to Tarkasnawa, a King of Mira within Arzawa complex, attests to the westernmost reaches of the late Hittites and their dependent principalities.

Karabel Luvian warrior monument carved in rock dated to the 13th century BC and at a distance of 30 km from İzmir, near Kemalpaşa, deciphered as having been dedicated to Tarkasnawa, a King of Mira within Arzawa complex, attests to the westernmost reaches of the late Hittites and their dependent principalities.

| Date | Occurrence |

|---|---|

| est. mid to end of third millennium BC | Luvians arrive and settle in, initially western, and gradually across southern Anatolia. |

| est. c. 1440 BC | The first recorded urban settlement which controlled the Gulf of İzmir, associated with the semi-legendary local ruler Tantalus, called the Phrygian and also associable with the Luvians and the Lydians, and deriving its wealth from the region's mineral reserves, is founded on or near Mount Yamanlar. A "Tomb of Tantalus" near this mountain, as well as an alternative tomb some sources associate with the same Tantalus on Mount Sipylus reached our day, scholars differing on associations that could be based on the one or the other. |

| est. c. 1370 BC | Part of the Lydian population, led by Tyrrhenus according to the accounts, obliged to leave their land due to famine, build themselves ships in the present-day harbor of İzmir and sail away in search of new homes and better sustenance, to finally arrive to Umbria where, according to one account (Herodotus), they lay the foundations of the future Etruscan civilization. |

| est. c. 1360 BC | Pelops, the son of Tantalus, abandons the city founded by his father and founds a kingdom in the Peloponnese, named after him. His sister Niobe remains associated with the "Weeping Rock" on Mount Sipylus. |

| c. 1200 BC | Late Hittites advance in western Anatolia, called at first as "Luwiya" and then as Arzawa in Hittite sources, is attested by a monument carved in rock in Karabel mountain pass near the modern city of Kemalpaşa, at about 30 km from İzmir. It is dated to the second half of the 13th century BCE during the reign of Tudhaliya IV and the male figure is identified as Tarkasnawa, King of Mira, matched with a name mentioned in Hattusa Hittite annals[1] |

| est. c. 1200 BC | First Hellenic colonists begin to appear along the western coasts of Anatolia. |

| est. c. 1194 BC – 1184 BC | Trojan War, some of whose wounds are healed in the thermal springs in the present-day Balçova district of İzmir, Greeks under Agamemnon having been advised the baths by an oracle. The still highly popular "Agamemnon Baths" is also the place where, reportedly, Asclepius first began to prophesy.[2] |

| 850 BC | Caravan Bridge, sometimes said to be the oldest extant bridge, a 13 m stone slab over the River Meles is built.[3] |

| 716 BC (or 680 BC) | Gyges of Lydia, the founder of Mermnad dynasty, seizes the throne of Lydia which will be held by his descendants until 546 BC and the dynasty will acquire a large part of Anatolia including Smyrna. |

Homer was also called Melesigenes (son of Meles) by the name of the River Meles which flows through İzmir and still carries the same name.

Homer was also called Melesigenes (son of Meles) by the name of the River Meles which flows through İzmir and still carries the same name.

| est. early 7th century BC | Refugees from the Ionian city of Colophon, admitted inside Smyrna by the city's Aeolian inhabitants, chase the natives, by deceit according to Herodotus, and Smyrna becomes the thirteenth city state of the Ionian union. |

| slightly before 668 BC | The first failed Lydian attempt to capture Smyrna, despite their seizure of the town and their advance within the walls of the fortress. |

| c. 600 BC | Lydian king Alyattes captures Smyrna along with several other Ionian cities and the city is sacked and destroyed, its inhabitants forced to move to the countryside to live for a time in "village-like fashion" according to contemporary sources. More recent research and restoration works in Old Smyrna by Ekrem Akurgal indicate that the city-temple dedicated to Athena, built a few decades before, saw only slight damage in the Lydian capture, was repaired swiftly and continued to be used. |

| c. 540 BC | The Median general Harpagus, serving the Persian Emperor Cyrus the Great captures Symrna along with other regions under Lydian rule in Anatolia, and destroys the city. |

| 333 BC | Alexander the Great conquers Smyrna, moves the city from its rather isolated location at the end of the gulf to the southern shore from where the future city will expand. Legends attribute the move for relocation to a dream of Alexander. |

| 323 – 280 BC | In the division of the provinces after Alexander's death, Antigonus I Monophthalmus receives Smyrna, along with Phrygia, Pamphylia and Lycia. It is his defeater, Lysimachus, King of Asia Minor between 301 and 281 BC, who displays a genuine interest to the city, initiating widescale public works in the intention of transforming it into an international portuary and cultural center on a par with Alexandria and Ephesus. Lysimachus even names the city, for a time, under his daughter's name, "Euredikeia". |

| 280 BC | In the climate of uncertainty reigning between Lysimachus's death and the Seleucid Emperor Antiochus I Soter's takeover, Smyrniots declare their independence for a brief period. |

| 278 BC | Galatians, arriving from Thrace, capture Smyrna and ransack the city. |

| 275 BC | Antiochus II defeats the Galatians and the city returns to Seleucid control. |

| 241 BC | Smyrna adheres to Attalus I, King of Pergamon. |

| 190 BC | Smyrna is transferred under Roman authority along with Pergamon. Eager to cultivate Roman connections, Smyrna becomes the first city in Asia to build a temple to the honor of the goddess Roma. |

| 130 BC | With the death of last King of the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon, Smyrna is taken under direct Roman administration. |

| 78 BC | Cicero visits Roman Smyrna. The Roman province of Asia will be administered by his younger brother, the propraetor Quintus Tullius Cicero between 61 and 59 BC. |

| 43 BC | The first settling of scores after the Assassination of Julius Caesar takes place in Smyrna when Publius Cornelius Dolabella, Julius Caesar's former favourite assigned to Syria by the Roman Senate, forces his way into the city where Trebonius, an accomplice of the assassins, held the office of proconsul and kills him. Before Dolabella's own death the year after, his assault, and particularly some damage he had inflicted on the city, was condemned at the time in Rome, including by Dolabella's father-in-law Cicero, who referred to the people of Smyrna as among Rome's "most trusted and oldest allies". |

| Common Era | |

| 124 | Emperor Hadrian visits Smyrna as part of his journeys across the Empire[4] |

| 155 or 156 AD | Polycarp (Saint Polycarp of Smyrna) is martyrized by stabbing in the amphitheater of the city after attempts to burn him at the stake fails, and the account, "The Martyrdom of Polycarp or the Letter to the Smyrneans" becomes one of the fundamental sources among early Christian writings. |

| 178 | A violent earthquake shakes Smyrna to its cores, causing immense damage and casualties. The city was rebuilt in a single year with the help of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, according to the orator Aelius Aristides. |

| 214 BC | Emperor Caracalla visits Smyrna, along with other cities in Anatolia and later Egypt, and a cult of Caracalla starts in the city. |

| 250 | Pionius is martyrized in Smyrna by burning on the gibbet. |

| 395 | Following the death of Theodosius I, when the political division between Eastern and Western Roman Empires acquires a permanent nature, Smyrna becomes part of the Eastern Roman Empire. |

| 1079 | First Seljuk Turkish horsemen begin to appear along the western regions of Anatolia, a few years after the Seljuk sultan Alp Arslan's 1071 victory over the Byzantine Empire in the Battle of Malazgirt and following his designation of Anatolia for seizure by Suleyman I of Rûm, son of a former contender to his throne, Kutalmış. |

| 1081 | Turkish forces loyal to Süleyman Bey and under the command of Tzachas Smyrna and immediately build a navy, the first ever recorded naval force in Turkish history, to harry the Aegean Sea and its coasts. |

| 1097 | The First Crusade siege of Nicaea (İznik) and the subsequent crusader victory in the First Battle of Dorylaeum allow the Byzantine forces under Alexios I Komnenos's brother-in-law John Doukas to recover much of western Anatolia, re-capturing Smyrna (İzmir), Chios, Rhodes, Mytilene, Samos, Ephesus, Philadelphia, and Sardis. |

| 1231–1235 | Emperor (of Nicaea) John III Doukas Vatatzes builds a new castle (Neon Kastron, later to be named "Saint Peter" by the Genoese, and "Okkale" by the Turks) that commands the now silted up inner bay of the city (present-day Kemeraltı bazaar zone). The Emperor spends much time in the summer palace he had had built in nearby Nymphaion (later Nif and present-day Kemalpaşa) and dies there in 1254. |

| 1261 | In the same year as his expulsion of the Latin Empire and re-capture of Constantinople, the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, seeking an ally against the danger posed by the Venetians and the papacy, signs the Treaty of Nymphaion with the Genoese and accords them considerable privileges within the empire's realm, commercial or otherwise, including that of setting up their own districts in the capital and in Smyrna. Galata quarter across the Golden Horn, to extend later on to the whole of Pera, present-day Beyoğlu, and Smyrna's core area along the inner bay with its castle become virtually independent Genoese possessions. |

| 1308 | Turkish ascendancy in Western Anatolia re-surges after two centuries and the Beylik of Aydin is founded with its capital in Birgi. |

| 1317 | Aydınoğlu Mehmed Bey captures İzmir's upper castle of Kadifekale from Byzantine forces. |

| 1329 | The Genoese merchants hand over the keys of the port castle (Okkale, Saint Peter) to Umur Beg. |

| 1333 | Ibn Battuta visits İzmir. He reports that most of the city is in ruins.[5] |

| 1334–1345 | Umur Bey transforms the Beylik of Aydin into a serious naval power with base in İzmir and poses a threat particularly for Venetian possessions in the Aegean Sea. Venetians organize an alliance uniting several European parties (Sancta Unio), composed notably of the Knights Templar, which organizes five consecutive attacks on İzmir and the Western Anatolian coastline controlled by Turkish states. In between, it is the Turks who organize maritime raids directed at Aegean islands.[6] |

| 1348 | Umur Bey dies and his brother and successor Hızır Bey concludes on 18 August an agreement with the Sancta Unio which, following its approval by the Pope, gives the Knights Templar the right to control and use the port castle (Saint Peter, Okkale). |

| 1390 | Ottoman sultan Bayezid I (the Thunderbolt) comes to İzmir shortly after he ascends the throne and smoothly captures the upper castle of Kadifekale. İzmir becomes Ottoman partially, with the exception of the port castle, and for the time, temporarily, for a decade. |

| 1402 | Three months after his victory over the Ottomans in the Battle of Ankara, Tamerlane comes to İzmir, lays a six-week siege on the port castle (Okkale, Saint Peter) in the unique battle of his career against a Christian power, captures the castle and destroys it. He massacred most of the Christian population, which constituted the vast majority in Smyrna.[7][8]

He handed the city over to its former rulers, the Aydinids, as he had done for other Anatolian lands taken over by the Ottomans. |

| 1416 | Aydinids (cited more often as İzmiroğlu) Cüneyd Bey re-builds Okkale in the intention of turning it into his power base, at the same time as he uses every occasion to hamper the resurgence of Ottoman power. |

| 1413–1420 | Popular revolts based in Manisa and Karaburun against the newly re-established Ottoman rule. |

| 1425 | Ottoman sultan Murad II has İzmiroğlu Cüneyd Bey executed, puts an end to the Beylik of Ayidin, and re-establishes Ottoman authority over İzmir, this time definite. For their aid in Cüneyd Bey's demise, the Knights Templar press the sultan for renewed authority over the port castle (Okkale), but the sultan refuses, giving them the permission to build another castle in Petronium (Bodrum) instead. |

| 1437 | In a practice started by Murad II and which will last until 1595 in seventeen near-consecutive periods, many of the shahzades (crown princes) of the Ottoman dynasty -fifteen in all- start receiving their education in government matters in neighboring Manisa, including two among the most notable, Mehmed II and Süleyman I. |

| 1472 | On 13 September, a Venetian fleet under Pietro Mocenigo, one of the greatest Venetian admirals, captures and destroys İzmir in a surprise attack, along with Foça and Çeşme. The Ottoman investment into İzmir will remain hesitant for more than a century, until the 17th century building of Sancakkale castle at a key location commanding access to the city and assuring its security. |

| 1566 | Ottoman capture of the Genoese island of Scio (Sakız, Chios), arguably to compensate for the loss of face suffered after the siege of Malta, puts an end to three centuries of entente between the Republic and the Turkish powers based along the Anatolian coast. At the same time, the European merchants which used the island and Çeşme across its shores as bases are tempted to seek a new port of trade and they are increasingly attracted to the small town of İzmir, administered at the level of a qadi instead of the stricter and more centralized authority of a pasha. |

| 1592 | Aydınoğlu Yakub Bey, a descendant of the formerly ruling dynasty, builds the oldest major Ottoman landmark in İzmir, the Hisar Mosque in Kemeraltı, adjacent to the decaying port castle of Okkale. |

| 1595 | The practice of assigning Ottoman dynasty members for administration of neighboring Manisa and its dependencies is abandoned, largely due to the growing insecurity in the countryside, precursor of Jelali Revolts, and a violent earthquake in the valley of Gediz deals a severe blow to the region's prosperity the same year. |

| 1605 | The first attested presence in community of Sephardi Jews, descendants of those evicted from Spain in 1492, in İzmir. |

| 1605–1606 | İzmir is menaced by the Jelali Revolts of Kalenderoğlu, Arap Said and Canbolat. |

| Date | Occurrence |

|---|---|

| 1619 | The French consulate in İzmir opens, moving in from Sakız (Chios). |

| 1621 | The English consulate in İzmir opens, moving in from Sakız (Chios). |

| 1624–1626 | İzmir is menaced by corsairs in three consecutive years, who leave each time after having levied a ransom, aggravating considerations for the city's safety. |

| 1630s | Local warlord Cennetoğlu, a brigand (sometimes cited as one of the first in line in western Anatolia's long tradition of efes to come) who in the 1620s had assembled a vast company of disbanded Ottoman soldiers and renegades, establish control over much of the fertile land around Manisa and, often in pact with the influent western merchant Orlando, trigger a movement of more commercially sensitive Greek and Jewish populations towards İzmir[9] |

| 1650–1665 | The construction by the Ottoman Empire of Sancakkale castle at a key location commanding access to the furthermost waters of the Gulf of İzmir, thus assuring İzmir's security and greatly improving its fortunes. |

| 1657 | Jean-Baptiste Tavernier visits İzmir for the second time and for a longer period. According to the detailed account he gave, İzmir then had a population of 90,000 of which 60,000 were Turks, and 15,000 Greeks[10] |

| 1671 | Evliya Çelebi visits İzmir. |

| 1676–1677 | A great plague epidemic, the first known pandemic on record for Ottoman İzmir claims 30,000 lives in İzmir and Manisa. |

| 1678 | Antoine Galland visits İzmir during a second Oriental tour, following an equally fruitful first visit across the eastern Mediterranean in 1673–1674 in the company of France's ambassador at the Sublime Porte, Marquis de Nointel. This time he writes the very detailed manuscript "Voyage á Smyrne" which will remain unedited until the year 2000. |

| 1678 | Exception made of probable presence in the region during Byzantine times, a community of Armenians is attested for the first time in Ottoman İzmir, refugees who had sought asylum from the rule of Safavid Shah Abbas I of Persia and were generously welcomed by the Ottoman Empire. On the eve of the Great Earthquake, estimates made for İzmir's population in sources like Paul Rycaut, Galland and others reached upwards of 80,000 in the ratio of seven Turks, two Greeks, one Jew and one Armenian, with other nationalities, many of whom played a pivotal role in shaping the city's fortunes, totalling barely a thousand.[11] |

| 1688 | Two successive earthquakes of great magnitude on 10 July and 31 July and a tsunami that ensued after the second causes great damage and shakes İzmir to its cores. The casualties number in the tens of thousands, the commercial activity in the city stops for years, and Sancakkale will have to be rebuilt. The earthquake will also trigger a movement among foreign merchants to move their residences to the İzmir suburb of Buca, and later on, also to Bornova. |

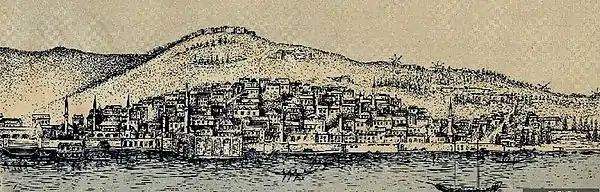

İzmir 1714 in an engraving by Henri Abraham Chatelain

| Date | Occurrence |

|---|---|

| 1707 | Established in the city only since decades, foreign merchants organize a riot centered in Buca. The riot leads in 1716 to the assignment in İzmir of Köprülü Abdullah Pasha, the first Ottoman administrator of the city who bore the title of pasha. |

| 1712 and 1717 | Two successive plague epidemics. The one in 1712 is particularly deadly and claims 10,000 lives. |

| 1739 | English traveller and anthropologist Richard Pococke visits İzmir. |

| 1744 | The completion of the building of the still-standing caravanserai of Kızlarağası Han in Kemeraltı. |

| 1763 | A fire destroys 2,600 houses, with a loss of $1,000,000. |

| 1766 | English traveller Richard Chandler visits İzmir and its surrounding region in search of antiquities on behalf of London Society of Dilettanti. |

| 1772 | A fire carries off 3,000 dwellings and 3,000 to 4,000 shops, entailing a loss of $20,000,000. |

| 1778 | A violent earthquake on 3 July and an ensuing fire that lasts until 8 July destroys the city. |

İzmir in 19th century European art

View of the site of Agora of Smyrna in an 1843 engraving

View of the site of Agora of Smyrna in an 1843 engraving Bornova (Bournabat) as imagined by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot in 1873

Bornova (Bournabat) as imagined by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot in 1873

| 1803–1816 | Katipzade family, controlling İzmir since the 1750s, reach the summit of their power with Katipzade Mehmed Pasha who rule the city and its vicinity under the official title of ayan accorded by the Sultan. They are the builders of the first governor's mansion in the city and the adjacent Yalı Mosque of very small dimensions in Konak Square, a symbol of İzmir to this day. Katipzade Mehmed Pasha is executed by the Sultan in 1816. |

| 1804 | The completion of the building of the still-standing caravanserai of Çakaloğlu Han in Kemeraltı. |

| 1806–1808 | Chateaubriand (1806) and Lord Byron (1808) briefly visit İzmir. |

| 1812–1816 | A four-year plague epidemic claims 45,000 lives in İzmir region. |

| 1823–1827 | İzmir's first newspaper, named "Smyrnéen" at first and "Spectateur orientale" later is published in French for four years. |

| 1831 | A cholera epidemic claims 3,000 lives in İzmir region, particularly among the Jewish community. Two still-standing landmarks of the city owe their existence to the epidemic: The Jewish Hospital, which becomes a pole of attraction that paves the way for the concentration of the city's Jewish population in Karataş, and St. Roch Hospital and Monastery, the present-day premises of İzmir Ethnography Museum, affectionately called Piçhane for having served as an orphanage for a period.[12] |

| 1836 | Charles Texier visits İzmir and conducts surface research on the remains of classical Smyrna and on those found on or near Mount Yamanlar. |

| 1837 | İzmir's last great plague epidemic claims 5,000 lives, especially among the Turkish population. A quarantine administration for incoming ships will be put in place as a consequence of the epidemic, in a quarter of the city that will be named Karantina. |

| 1840 | Exports from the port of Trabzon exceed those from İzmir for the first time and İzmir thus loses its virtual monopoly on exports among Ottoman ports for the first time as far back as the records are kept. |

| 3 July 1845 | A great fire ravages the central quarters of İzmir. Personal interventions from the sultan Abdülmecid I will play a fundamental during the reconstruction effort. |

| 1850 | İzmir becomes the vilayet center for the first time and for a brief period. The vilayet is still called under the name of its former center, Aydın. |

| 1850 | Gustave Flaubert visits İzmir, noting, after having watched the sunset from Kadifekale, "qu'il n'en avait jamais vu de si belle". |

Images of cosmopolitan 19th century İzmir

A Turkish quarter in 19th century İzmir: Kadifekale

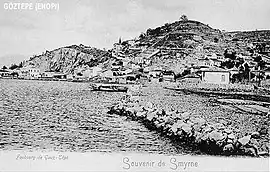

A Turkish quarter in 19th century İzmir: Kadifekale A Greek quarter in 19th century İzmir: Göztepe (Enopi), with Susuzdede (Agios Agapis) hill in the background

A Greek quarter in 19th century İzmir: Göztepe (Enopi), with Susuzdede (Agios Agapis) hill in the background A Jewish quarter in 19th century İzmir: Karataş

A Jewish quarter in 19th century İzmir: Karataş A European quarter in 19th century İzmir: Bornova

A European quarter in 19th century İzmir: Bornova

| Date | Occurrence |

|---|---|

| 1850–1851 | Alphonse de Lamartine visits İzmir for a second time (the first in 1833) and having fallen under the spell of the city and the country, buys a farm in Tire that he manages for a time before returning to France where he writes important works related to Turkey. |

| 1851–1854 | The first cadastral plan of İzmir is made by the engineer Luigi Storari, a Republican in exile from Padua, who also draws the plans for the Istanbul quarter of Aksaray after a fire in 1854 and publishes a guide on İzmir in Torino in 1857. |

| 1856 | George Rolleston holds a post in the British Civil Hospital during the Crimean War and presents a detailed report on İzmir to the Secretary of State for War. According to Rolleston, İzmir's population could be estimated as amounting to 150,000 people, in accordance with the 1849 census, two-thirds being either Turks or Greeks, whose numbers were until lately equal, but came to be proportioned as 45,000 Turks against 55,000 Greeks, poverty and conscription lately acting as a check against the increase of the former.[13] The first horse races in the modern sense start to be organized in Buca. |

| 1860 | In response to a questionnaire by the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Sir Henry Bulwer, the experienced consul Charles Blunt responds by stating that in 1830 the city contained 80,000 Turkish inhabitants and 20,000 Christians, whereas in 1860, the Turks numbered 41,000 and the Christians 75,000. According to Blunt, the general condition of the province of İzmir was constantly improving due to increasing cultivation and agricultural production. However, because of the Turkish lack of manpower, this improvement was "...more generally to the advantage of the Christian races. |

| 1856–1867 | The construction of the first railroad connection in the Ottoman Empire, between İzmir (in partance from the simultaneously built Alsancak train station) and Aydın (130 km), is contracted out to a British company who will finish it in eleven years. |

| 1863–1866 | The construction of the second railroad connection in the Ottoman Empire, between İzmir (in partance from the simultaneously built Basmane train station) and Turgutlu (93 km), contracted out at first to a British, then to a French company, who manages to finish it in three years, a few months before İzmir-Aydın line. |

| 1865 | The quarter of Karataş is opened for residential use and becomes, almost immediately and practically exclusively, İzmir's Jewish quarter. İzmir-Menemen railroad enters into service the same year, leading to urban growth in Karşıyaka (Kordelio) on the northern shore of the gulf. |

| 1867 | İzmir becomes the vilayet center for the second time and definitely. The vilayet will continue to be under the name of its former center, Aydın, until the demise of the Ottoman Empire. Instability will characterize the first decades of the governorship in İzmir, with, for example, five consecutive governors only for the year 1875. |

| 1867–1876 | Upon the destruction by a seismic wave of the previous quays built in wood, start of the construction of new port installations. With the project, completed in ten years by a French company and by British engineering, the wharf (Pasaport Wharf), as well as a 3250 m long combination of a landing stage, of a street served by a tram line and of an esplanade (Kordon) comes into existence, all built on land gained from the sea, and profoundly changing the city's look. The final remains of the old port castle (Okkale) and former yalı type residences along Kordon are demolished to provide space for the wharf and the street, along which new buildings of western tastes and styles will be rapidly built. The French customs house built within the project, reportedly designed by Gustave Eiffel, is today's Konak Pier upmarket shopping center. |

| 1868–1895 | A municipal administration is constituted in İzmir, in line with the Ottoman reforms in the matter. İzmir municipality will only mature in time, becoming active as of 1874, being scinded in two in 1880 to administer the more westernized city core and the more traditional suburbs separately, being reunited in 1889, and possessing its own building only in 1891. A stable municipal administration in İzmir is generally admitted to start a generation after its founding under Eşref Pasha (1895–1907).[14] |

| 1874 | Start of urban ferry services between İzmir proper and Karşıyaka by a British company under an Ottoman imperial lease accorded by Abdülhamid II and named "Hamidiye" for this reason. A second shipping company puts two other ferries in service starting 1880, followed in 1884 by a third company. Very rapidly, it becomes fashionable for İzmir's European, Levantine, Ottoman minority and later Turkish rich to build or purchase houses in Karşıyaka. |

| 1886 | In a work of engineering of considerable scale for its time, the course of the Gediz River in its alluvial delta is diverted northwards, thus preventing it from joining the sea inside the Gulf of İzmir, where the shallows caused by the silt the river brought had seriously started to render navigation difficult and jeopardize İzmir's portuary future.[15] |

| 1886–1897 | A Belgian company builds İzmir's first running water system, today still based on the same location of Halkapınar quarter. |

| 1890 | The first recorded football match in Turkey is played in Bornova, İzmir, between local youths and British sailors on shore leave. |

| 1892–1895 | A railway connection for a steam-powered tram was considered to be built between İzmir and Çeşme, itself internationally famous for its grapes and on deemed as being on its way to become a second large port for the region. The line, based on the model of a line built in the Peloponnese presenting similar characteristics, was projected to serve a population of around 350,000 (250,000 for İzmir and the rest along the line in Karaburun Peninsula) and which would have halved the duration of a journey between Sakız (Chios), was submitted by the Ottoman Bank to French (1892) and then to German (1895) entrepreneurs but, despite being potentially promising, was not concretized and its initial works ended up by tracing a phantom track. In the meantime, especially with the flow of immigrants from Thessaly and Crete, the population trends in Karaburun Peninsula started to bend in favor of the Turks. |

| 1901 | Izmir Clock Tower, designed by the Levantine French architect Raymond Charles Père, with the clock itself a gift of German Emperor Wilhelm II is built to commemorate the 25th anniversary of Abdul Hamid II's accession to the throne, and becomes a symbol for the city |

| 1907 | Asansör building in Karataş, one of İzmir's landmarks, is erected as a public service by the wealthy Jewish banker Nesim Levi Bayraklıoğlu. |

| 1915 | In a naval campaign that involved İzmir directly during the World War I, a British fleet commanded by the Vice-Admiral Peirse arrives off the deep end of the Gulf with armoured cruiser HMS Euryalus, pre-dreadnoughts HMS Triumph and HMS Swiftsure, a seaplane carrier, and minesweepers and bombs defence positions between 5 – 9 March causing six casualties among Turkish soldiers. The fleet's tasks are to destroy the protecting forts and clear the approach minefields, neither of which are accomplished. Allied demands transmitted through the U.S. consul in İzmir George Horton for surrender of the city are rebuffed by the governor Evrenoszade Rahmi Bey and on 15th, the force withdraws.[16] |

| 1919–1922 | Occupation of İzmir as of 15 May 1919, Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922). |

| 1922 | Re-capture of İzmir by the Turkish army on 9 September 1922. Great Fire of Smyrna between 13 September and 17 September. Appointment of the first governor of Ankara Turkish Grand National Assembly government and by extension of Republican Turkey on 20 September. |

| September–October 1922 | A short stay in Istanbul that was to acquire importance for American literature, from end-September to mid-October as Toronto Daily Star reporter, leads Ernest Hemingway to write his first short story to appear in his first collection of stories, In Our Time, published 1925. This story, titled "On the Quai at Smyrna", probably based on original material derived from a British officer who was present in İzmir early in the period, was written in a deliberately disorientating style with a sarcastic tone and observations directed at all sides to the conflict.[17] |

| 1923 | Signature between Greek and Turkish delegations of the agreement for a Population exchange between Greece and Turkey in the frame of Lausanne Conference on 30 January. |

| Date | Occurrence |

|---|---|

| 1923 | İzmir Economic Congress is held under the chairmanship of Mustafa Kemal Pasha between 17 February – 3 March and it lays the foundations of the economic policy for the early years of the Republic of Turkey, founded the same year. |

| 1929 | İzmir Alsancak Stadium is built over part of former Darağacı (Gallows) quarter.[18] |

| 1932 | After preliminary explorations made in 1927, the first organized excavations at the site of Classical Period Smyrna, centered around the Agora of the ancient city, are carried out jointly by the German archaeologist Rudolf Naumann and Selâhattin Kantar, the director of İzmir and Ephesus museums. Between 1932 and 1941, they uncover a large part of the agora and publish the results of their works with contributions made also by the Austrian archaeologist Franz Miltner, first the first time in 1934, to be compiled more comprehensively in 1950.[19] |

| 1936 | The fifth İzmir International Fair is the first that is held at its present location of Kültürpark where it acquires the proportions of an ongoing important annual commercial and cultural event of international scale. |

| 1948 | The first organized excavations at the site of Archaic Period Smyrna are started by an Anglo-Turkish team under Professors John M. Cook and Ekrem Akurgal, to be pursued by Akurgal on a continuous basis as of 1966 and to be managed after 1993 by Akurgal's wife Meral Akurgal. |

| 1954 | Start of the construction of the Port of Alsancak, still used and extended, and privatized in 2007. Kuşadası district transferred to Aydın Province |

| 1955 | Ege University, İzmir's first university to start courses, is founded with present-day campus in Bornova. |

| 1964 | The multi-use stadium İzmir Atatürk Stadyumu, Turkey's largest at the time (today the second largest) is built in view of the Mediterranean Games. |

| 1971 | İzmir hosts the Mediterranean Games. |

| 1982 | Dokuz Eylül University, İzmir's second largest, is founded with present-day campus in Buca. |

| 1984 | İzmir Archaeology Museum, first set up in Ayavukla Church (Gözlü Church) in Basmane popular quarter, with a second museum in Kültürpark added in 1951, moves to its premises covering 5.000 sqm in Bahribaba Park. |

| 1987 | İzmir's new airport, Adnan Menderes Airport, enters into service. A new international terminal was added in 2006. |

| 1990 | Aegean Free Zone, the first production-based free zone in Turkey and the leader among the country's 19 others, opens as a Turkish-U.S. joint-venture in İzmir's Gaziemir district, to reach a total portfolio of 302 notable companies by 2006, generating more than $4 billion annually in international trade. It also houses the world's fifth Space Camp. |

| 1992 | İzmir's third university and first institute of technology, İzmir Institute of Technology is founded, with present-day campus in Urla. |

| 1995–2000 | The first line of İzmir Metro, extending from Üçyol station in Hatay to Bornova along a length of 11.6 km (7.2 mi) is built and enters into service. |

| 1998 | İzotaş, the new bus terminal in İzmir's Altındağ suburb, a city within the city in practical terms, enters into service. |

| 2002 | İzmir's fourth and fifth universities, İzmir University of Economics, with campus in Balçova, and Yaşar University, are founded. Both are private sector initiatives. |

| 2004 | In keeping with a move for decentralization of administrative services in the rapidly growing city, İzmir Hall of Justice moves from Konak Square to its new premises, the largest and the most modern in Turkey, in Bornova district.

|

| 2005 | İzmir hosts the Summer World University Games (Universiade). |

| 2006 | İzmir hosts 2006 European Seniors Fencing Championship. |

| 2008 | An open air zoo called İzmir Natural Life Park, 425,000 square meters in area, is opened in Sasalı, a depending municipality of İzmir metropolitan district of Çiğli on the delta of the Gediz River. |

| 2008 | Ahmet Adnan Saygun Art Center, built by İzmir Metropolitan Municipality by involving world-famous companies in music and construction, is opened over an area of 21.000 m2 in Güzelyalı neighborhood to honor a famous native of the city. |

Sources

- M. Çınar Atay (1978). Tarih içinde İzmir [İzmir throughout history] (in Turkish). Yaşar Education and Culture Foundation.

- Ekrem Akurgal (2002). Ancient Civilizations and Ruins of Turkey: From Prehistoric Times Until the End of the Roman Empire. Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7103-0776-4.

- George E. Bean (1967). Aegean Turkey: An archaeological guide. Ernest Benn, London. ISBN 978-0-510-03200-5.

- Cecil John Cadoux (1938). Ancient Smyrna: A History of the City from the Earliest Times to 324 A.D. Blackwell Publishing.

- Daniel Goffman (2000). İzmir and the Levantine world (1550–1650). University of Washington. ISBN 0-295-96932-6.

- "Random Facts about Great Fires in History". Archived from the original on 23 October 2010.

Footnotes

- David Hawkins (1998). Tarkasnawa, King of Mira. Anatolian Studies, Vol. 48. See also; Bilgin, Tayfun. "Karabel". Hittite Monuments.

- George E. Bean (1967). Aegean Turkey: An archaeological guide. Ernest Benn, London. ISBN 978-0-510-03200-5.

- M. G. Lay; James E. Vance (1992). Ways of the World. Rutgers University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-8135-2691-1.

- Ronald Syme (1998). "Journeys of Hadrian" (PDF). Dr. Rudolf Hbelt GmbH, Bonn – University of Cologne.

- Gibb, H.A.R. trans. and ed. (1962). The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354 (Volume 2). London: Hakluyt Society. pp. 445–447.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Hans Theunissen. "Venice and the Turcoman Begliks of Menteşe and Aydın" (PDF). Leiden University, The Netherlands, 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2005. Retrieved 21 February 2007.

- Ring, Trudy, ed. (1995). International dictionary of historic places (1. publ. in the USA and UK. ed.). Chicago [u.a.]: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 351. ISBN 9781884964022.

Timur... sacked Smyrna and massacred nearly all of its inhabitants

- Foss, Clive (1976). Byzantine and Turkish Sardis. Harvard University Press. p. 93. ISBN 9780674089693.

Tamerlane determined to conquer Smyrna... In December 1402, Smyrna was taken and destroyed, its Christian population massacred.

- Edhem Eldem; Daniel Goffman; Bruce Alan Masters (1999). "İzmir: From village to colonial port city". The Ottoman City Between East and West: Aleppo, Izmir, and Istanbul. Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-521-64304-X.

- limited preview Charles Joret (2005). Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, cuyer, baron d'Aubonne, chambellan du Grand lecteur (in French). Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1-4212-4722-4.

- Sonia P. Anderson (1989). An English Consul in Turkey: Paul Rycaut at Smyrna, 1667–1678. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820132-X.

- Zeynep Mercangöz, eds. M. Kiel, N. Landmann, H. Theunissen (23 August 1999). "New approaches to Byzantine influence on some Ottoman architectural details: Byzantine elements in the decoration of a building in İzmir" (PDF). Utrecht University, Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Turkish Art. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2003.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - George Rolleston. Report on Smyrna. year=1856.

- Erkan Serçe (1998). İzmir'de Belediye (1868–1945) Tanzimat'tan Cumhuriyet'e (Municipal administration in İzmir (1895–1945): From Tanzimat to the Republic) (in Turkish). Dokuz Eylül University, İzmir. ISBN 975-6981-06-7.

- It is possible that the present channel is closer to the mouth of the river as it used to flow in ancient times, since Herodotus says that it was close to Phocaea, as it is now, although when it changed to the south is not known. With the rapid silting process, the depending town of Menemen, which was almost on the shore in the beginning of the 18th century, had its harbor structures hours from the town towards the end of the same century and is an entirely inland center today.

- "War in the Mediterranean – 1915". Archived from the original on 28 November 2006. Retrieved 21 February 2007. "İzmir Bombardımanı" (in Turkish). Turkish Historical Society (TTK). Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2007.

- Himmet Umunç. "Hemingway in Turkey: Historical contexts and cultural intertexts" (PDF). Boğaziçi University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2010.

- "Üstü stad, altı mezar (Stadium on the surface, cemetery below)" (in Turkish). Radikal. Archived from the original on 4 January 2005. Retrieved 31 December 2004.

- Rudolf Naumann – Selahattin Kantar (1950). "Literatur zu Smyrna: Die Agora von Smyrna. Bericht Äuber die in den Jahren 1932–1941 auf dem Friedhof Namazgah zu Izmir von der Museumsleitung in Verbindung mit der Tuerkischen Geschichtskommission durchgefuehrten Ausgrabungen" (PDF) (in German). Istanbuler Forschungen 17, s. 69 – 114, Berlin.

Further reading

Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Izmir.

- Published in the 19th century

- William Hunter (1803), "Letter XI", Travels through France, Turkey, and Hungary, to Vienna, in 1792, London: Printed for J. White ... by T. Bensley ..., OCLC 10321359, OL 14046026M

- Josiah Conder (1824), "Smyrna (Izmir)", Syria and Asia Minor, London: James Duncan, OCLC 8888382

- Published in the 20th century

- Wratislaw (1922). "Smyrna in the 17th Century". Blackwood's Magazine.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.