Tokhtamysh

Tokhtamysh (Kazakh: Тоқтамыс; Tatar: Тухтамыш, romanized: Tuqtamış; Persian: توقتمش;[n 1] c. 1342 – 1406) was the Khan (ruler) of the Golden Horde, who briefly succeeded in consolidating the Blue and White Hordes into a single polity.[1]

| Tokhtamysh | |

|---|---|

| Khan | |

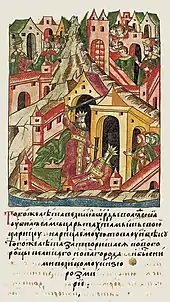

Depiction of Tokhtamysh in the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible (16th century) | |

| Khan of the Golden Horde Eastern Half (White Horde) | |

| Reign | 1379–1380 |

| Predecessor | Tīmūr Malik |

| Successor | himself, as khan of the Golden Horde |

| Khan of the Golden Horde | |

| Reign | 1380–1396 |

| Predecessor | ʿArab Shāh |

| Successor | Quyurchuq and Tīmūr Qutluq |

| Khan of the Tatar Siberian Khanate | |

| Reign | 1400–1406 |

| Predecessor | none |

| Successor | Chekre |

| Born | c. 1342 White Horde |

| Died | 1406 Tyumen |

| Dynasty | Borjigin |

| Father | Tuy Khwāja |

| Mother | Kutan-Kunchek |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Tokhtamysh belonged to the royal Mongolian dynasty of Borjigin, tracing his ancestry to Genghis Khan. Spending most of his younger years fighting against his father's cousin Urus Khan and his sons, Tokhtamysh sought help from the Turco-Mongol warlord Timur with whose help he succeeded in defeating his enemies.

Tokhtamysh rose to power during a tumultuous period in the Golden Horde, which was severely weakened after a long period of division and internecine conflict. From a fugitive, Tokhtamysh had become a powerful monarch, quickly solidifying his authority in both wings of the Golden Horde. Encouraged by his success, as well as the growth of his manpower and wealth, Tokhtamysh went on a military expedition to the Russian principalities, sacking Moscow in 1382. He reasserted the Tatar-Mongol hegemony over its Russian vassals and brought about the resumption of payment of tribute by the vassals.

A turning point in Tokhtamysh's rule was his military confrontations with his former protector Timur, who invaded the Golden Horde and twice defeated Tokhtamysh. Crushing defeats for the Golden Horde undid all Tokhtamysh's previous achievements and ultimately led to his own destruction.

Tokhtamysh has been called the last great ruler of the Golden Horde.[2][3]

Ancestry

According to the detailed genealogies of the Muʿizz al-ansāb and the Tawārīḫ-i guzīdah-i nuṣrat-nāmah, Tokhtamysh was a descendant of Tuqa-Timur, the thirteenth son of Jochi, the eldest son of Chinggis Khan. They provide the following ancestry: Tūqtāmīsh, son of Tuy-Khwāja, the son of Qutluq-Khwāja, the son of Kuyunchak, the son of Sārīcha, the son of Ūrung-Tīmūr, the son of Tūqā-Tīmūr, the son of Jūjī.[4] According to Muʿīn-ad-Dīn Naṭanzī (previously known as the "Anonymous of Iskandar"), Tokhtamysh's mother was Kutan-Kunchek of the Khongirad tribe.[5] Older scholarship followed the inaccurate testimony of Naṭanzī in making Urus Khan and, by extension, Tokhtamysh, descendants of Jochi's son Orda. This erroneous view was abandoned only gradually, first for Tokhtamysh, and later for Urus.[6] Although Urus and Tokhtamysh are often described as uncle and nephew, they were in fact fourth cousins.

Opposition to Urus Khan

Tokhtamysh's father, Tuy Khwāja, was the local ruler of the Mangyshlak peninsula. He refused to join the forces of his cousin and suzerain, Urus, the khan of the former Ulus of Orda centered on Sighnaq, for a campaign to subdue Sarai, the traditional capital of the Golden Horde. Offended and wary of any opposition to his authority, Urus had Tuy Khwāja executed. The young Tokhtamysh fled, then submitted to his father's murderer, and was forgiven on account of his youth.[7] In 1373, while Urus was asserting himself at Sarai, Tokhtamysh gathered a group of Urus' opponents and attempted to make himself khan in Sighnaq. Urus immediately advanced against them, and Tokhtamysh fled, only to return, submit, and be forgiven again.[8] When Urus took over Sarai in 1375, Tokhtamysh took the opportunity to flee again. He sought refuge at the court of Timur (Tamerlane), where he arrived in 1376. Winning his favor and support, Tokhtamysh installed himself at Otrar and Sayram on the Syr Darya in 1376, raiding into Urus Khan's territory. Urus' son Qutluq Buqa attacked and defeated Tokhtamysh, although he himself suffered a fatal wound. Tokhtamysh fled to Timur once more, and returned with an army to fight his enemies. However, he was defeated again, this time by Urus' son Toqtaqiya. Wounded, Tokhtamysh escaped by swimming across the Syr Darya and once more went to Timur's court, at Bukhara. Here he discovered that Urus was advancing in his pursuit, and soon Urus' envoys arrived, demanding Tokhtamysh's extradition. Timur refused to do so and gathered his own forces to oppose Urus. Following a three-month standoff in the winter of 1376–1377, Urus returned home, while Timur's forces succeeded in taking Otrar. Learning of Urus' death, Timur declared Tokhtamysh the new khan, and returned to his own capital, Samarkand.[9]

Rise to power

Urus was succeeded as khan by his son Toqtaqiya, who died after two months, and then by his other son, Tīmūr Malik. As before, Tokhtamysh had little luck fighting against a son of Urus, and he was easily defeated by Tīmūr Malik. Tokhtamysh fled to Timur's court once again. Hearing that Tīmūr Malik spends his time in drinking and pleasures and ignores affairs of importance, and that the exasperated people desire Tokhtamysh to rule them, Timur sent his forces to Sawran and Otrar, which surrendered. Advancing on Sighnaq, they defeated the enemy at Qara-Tal, and captured and executed Tīmūr Malik, betrayed by his own emirs, in 1379. Tokhtamysh was now installed as khan in Sighnaq, and he spent the rest of the year establishing his authority and harnessing his resources for his next target, Sarai.[10]

In 1380, Tokhtamysh advanced westward, intent on taking over Sarai and the central and western portions of the Golden Horde. His military power intimidated his former host Qāghān Beg in the Ulus of Shiban and Qāghān Beg's cousin, the reigning khan ʿArab Shāh, who both submitted to Tokhtamysh. Now khan at Sarai, he crossed the Volga to eliminate the powerful beglerbeg Mamai, master of the westernmost portions of the Golden Horde. Weakened by his defeat at the hands of the Russians at the Battle of Kulikovo earlier that year, and by the death of his puppet khan Tūlāk, Mamai was defeated by Tokhtamysh on the Kalka river in the autumn of 1381, after Tokhtamysh had enticed away a number of Mamai's emirs. Mamai fled to the Crimea, but was eventually eliminated by Tokhtamysh's agents, who had followed in pursuit, in late 1380 or early 1381.[11]

From a fugitive, Tokhtamysh had become a powerful monarch, the first khan in over two decades to rule both halves (wings) of the Golden Horde. In the space of a little over a year, he had made himself master of the left (eastern) wing, the former Ulus of Orda (called White Horde in some Persian sources and Blue Horde in Turkic ones), and then also master of the right (western) wing, the Ulus of Batu (called Blue Horde in some Persian sources and White Horde in Turkic ones). This promised to restore the greatness of the Golden Horde after a long period of division and internecine conflict. Tokhtamysh proceeded to solidify his authority with wisdom and restraint. Already in early 1381, he restored peace with the Genoese of the Crimea, ensuring himself a steady income. He similarly sought the cooperation of the emirs and tribal chieftains by confirming the privileges that had been conferred to them in the past.[12]

Campaign against Moscow

Encouraged by his success, as well as the growth of his manpower and wealth, Tokhtamysh next turned to the Russian principalities, although he did not necessarily seek a conflict from the start. Similarly, the Grand Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal, Dmitry Donskoy had recently defeated Mamai at great cost at Kulikovo, and was not looking for a confrontation, as he would have had difficulty to muster a great army again. He duly acknowledged Tokhtamysh as the new khan and his suzerain, but although he sent rich gifts, Dmitrij withheld the payment of tribute. When Tokhtamysh's envoy, Āq Khwāja, came to invite the Russian princes to the khan's court for the confirmation of their diplomas of investiture, he was faced with so much hostility by the population, that he turned back after reaching Nižnij Novgorod.[13]

Tokhtamysh prepared for war in 1382. Intending to catch his enemy by surprise, he began by ordering the arrest and robbing of Russian merchants on the Volga and the confiscation of their boats. Crossing the river with his entire army, he attempted to advance secretly, but attracted much attention. Seeking to ingratiate himself with the khan, Grand Prince Oleg Ivanovič of Rjazan' placed himself at the khan's disposal, pointing out the fords over the Oka river; Grand Prince Dmitrij Konstantinovič of Nižnij Novgorod also submitted readily and sent his sons Vasilij and Semën to join Tokhtamysh's campaign as guides. Grand Prince Dmitrij of Moscow did not submit, but left a strong garrison in his capital under the Lithuanian prince Ostej and sought out the greater safety of Kostroma, from where he hoped to gather greater forces. After taking Serpukhov, Tokhtamysh's forces reached and besieged Moscow on 23 August 1382. Three days later, the citizens were tricked into surrendering by Vasilij and Semën of Nižnij Novgorod, and Tokhtamysh's troops stormed into the city, slaughtering, plundering and finally razing it for the insubordination of its ruler. Other cities taken by the Mongols during the campaign included Vladimir, Zvenigorod, Jur'ev, Perejaslavl'-Zalesskij, Dmitrov, Kolomna, and Možajsk. On his way back, Tokhtamysh also sacked Rjazan', despite the cooperation of its prince.[14]

Later relations with the Russian principalities

After the submission of the Russian princes and the resumption of their tribute, Tokhtamysh adopted more conciliatory policies toward them. Dmitrij of Moscow razed Rjazan' in vengeance for Oleg Ivanovič's collaboration with Tokhtamysh against Moscow, but suffered no punishment for it. Mihail Aleksandrovič of Tver' was invested as Grand Prince of Vladimir and visited Tokhtamysh's court with his son Aleksandr, but never succeeded in entering into possession of the Grand Principality, as Tokhtamysh soon forgave Dmitrij of Moscow. Dmitrij had submitted, surrendered his eldest son Vasilij Dmitrievič as hostage, and promised to pay tribute, duly dispatched in 1383. When Dmitrij Konstantinovič of Nižnij Novgorod died the same year, Tokhtamysh granted that principality to his brother Boris Konstantinovič, but gave Suzdal' to Dmitrij's sons Semën and Vasilij. In 1386, Dmitrij of Moscow's son Vasilij, hostage at Tokhtamysh's court, escaped to Moldavia and made his way to Moscow via Lithuania. Despite some tension, Moscow did not suffer any consequences. On the contrary, when Dmitrij left his son Vasilij the Grand Principality of Vladimir in his will in 1389, Tokhtamysh sanctioned it through his envoy, Shaykh Aḥmad. Semën and Vasilij of Suzdal' expelled their uncle Boris from Nižnij Novgorod, but he tracked down Tokhtamysh on campaign and returned with a new investiture from the khan in 1390. Russian recruits subsequently served Tokhtamysh in Central Asia.[15] In 1391 Tokhtamysh sent his commander Beg Tut to ravage Vjatka, presumably in response to the depredations of the Ushkuyniks, buccaneers along the Volga; but the buccaneers launched a revenge raid on the area of Bolghar. Seeking cooperation against this and other threats, Tokhtamysh received Vasilij I of Moscow in his camp and invested him with the domain of Nižnij Novgorod despite the protests of its princes. Despite his sack of Moscow in 1382, Tokhtamysh had strengthened the power and wealth of its ruler in the end, helping set it on the path to annexing other Russian, and later Mongol polities.[16]

Initial conflict with Timur

In 1383, taking advantage of Timur's preoccupation with affairs in Persia, Tokhtamysh restored the Golden Horde's authority over the semi-autonomous Ṣūfī Dynasty in Khwarazm, apparently without provoking his former patron.[17] Under pressure from his emirs to provide profitable campaigns for plunder and perhaps possessed by the traditional ambitions of his predecessors, Tokhtamysh crossed the Caucasus with a large force (5 tumens, 50,000 troops) during the winter of 1384–1385, invading Jalayirid Azerbaijan. He captured the capital, Tabriz, by storm and ravaged the neighboring area for ten days, before retiring with his plunder, including some 200,000 slaves, among them thousands of Armenians from the districts of Parskahayk, Syunik, and Artsakh.[18] Either to take advantage of Jalayirid weakness or to preempt the expansion of the Golden Horde into the area, Timur proceeded to conquer Azerbaijan in 1386. He was wintering in nearby Karabakh in 1386–1387, when Tokhtamysh crossed the mountains in the spring of 1387 and headed straight for him. Despite being taken by surprise and being nearly defeated, Timur's commanders rallied and succeeded in repelling Tokhtamysh's attack with the help of timely reinforcements led by Timur's son Mīrān Shāh. Timur showed remarkable leniency to the captured warriors of Tokhtamysh, feeding and clothing them and allowing them to return home. Whether this was a sign of respect toward a royal descendant of Chinggis Khan or an attempt to defuse an unnecessary conflict on an unwanted front is unclear.[19]

Despite his defeat and a subsequent message seeking to defuse the hostility, Tokhtamysh continued to provoke his former protector. While Timur remained in Persia, in the winter of 1387–1388, Tokhtamysh overran Central Asia, where part of his forces besieged Sawran, while another crossed Khwarazm to besiege Bukhara. Timur's commanders prepared to defend Samarqand and other towns against the expected continued advance of Tokhtamysh, and Timur himself headed back from Shiraz to Samarqand with his main forces in February 1388. Learning of the enemy's movements, Tokhtamysh's forces retreated. Timur was now convinced that a serious contest with Tokhtamysh was inevitable. He overthrew the Ṣūfī Dynasty of Khwarazm for its collusion with Tokhtamysh and razed to the ground its capital, (old) Gurgānj, in 1388. Increasingly aware that he was outmatched, Tokhtamysh sought to create an anti-Timurid coalition, reaching out to neighboring rulers (including the Mamluk sultan Barqūq) concerned by Timur's power. Tokhtamysh attempted to take Sawran again in 1388, was driven off by Timur in the snowy January of 1389, but made another attack on Sawran later in the year. It also failed, but Tokhtamysh's forces pillaged the neighborhood and plundered the town of Yasī (now Turkistan) before retreating to safety when Timur defeated Tokhtamysh's vanguard and crossed the Syr Darya in pursuit. Timur seized Sighnaq but then diverted his attention to Tokhtamysh's allies farther east.[20]

First Timurid invasion into the Golden Horde and its aftermath

Timur determined to take the initiative and strike decisively into Tokhtamysh's core territories. Gathering a large army, he set out in February 1391 from Tashkent, ignored Tokhtamysh's envoys seeking peace, and struck into the territories of the former Ulus of Orda. But for four months of traveling and hunting, Timur failed to catch up with Tokhtamysh, who had seemingly retreated northwards. Only after reaching the headwaters of the Tobol did Timur discover that Tokhtamysh was regrouping to the west, across the Ural and planning to defend the crossing. Timur advanced on the Ural and crossed it farther upstream, causing Tokhtamysh to retreat in the direction of the Volga, where he could expect the arrival of reinforcements from the Crimea, Bolghar, and even Russia. Determined to preempt this, Timur caught up with Tokhtamysh and forced him to give battle at the Kondurcha river, on 18 June 1391. The hard-fought battle ended in the rout of Tokhtamysh's forces and his flight from the battlefield; many of his soldiers, trapped between the enemy and the Volga, were captured or slaughtered. Timur and his victorious army celebrated for over a month by the banks of the Volga. Surprisingly, he did not attempt to consolidate his control over the area before heading for home.[21]

At their request, Timur left behind two princes descended from Tuqa-Timur, Tīmūr Qutluq (son of Qutluq Tīmūr) and Kunche Oghlan (Tīmūr Qutluq's paternal uncle), as well as the Manghit emir Edigu (Tīmūr Qutluq's maternal uncle).[22] This is sometimes interpreted as Timur's investiture of Tīmūr Qutluq as khan,[23] but that seems unlikely: the three were supposed to recruit additional troop for the Timurid army. Only Kunche Oghlan remained faithful to his vow, and returned to Timur with his recruits, before deserting Tokhtamysh the next year. Meanwhile, Tīmūr Qutluq and Egidu struck out on their own with a growing following and appear to have declared Tīmūr Qutluq khan in the left (eastern) wing of the Golden Horde. One of Tokhtamysh's commanders, Beg Pūlād (possibly a grandson of Urus Khan), who had escaped from the Battle of Kondurcha, had declared himself khan at Sarai in the expectation that Tokhtamysh had perished.[24]

Tokhtamysh had survived and still commanded sufficient authority and manpower to strike back. Defeating and expelling Beg Pūlād from Sarai, Tokhtamysh chased him into the Crimea and, after besieging him in Solkhat, finally killed him. Another would-be challenger in the Crimea, Tokhtamysh's second cousin Tāsh Tīmūr, temporarily recognized Tokhtamysh's rule but retained some autonomy. Tokhtamysh dealt similarly with Edigu, coming to terms with him in exchange for his submission, and leaving him with autonomous authority in the east, greatly weakening the position of Tīmūr Qutluq. Tokhtamysh felt powerful enough to demand tribute from the Polish King Władysław II Jagiełło in 1393 for the lands his father, Grand Duke Algirdas of Lithuania, had taken from the Golden Horde in the past. His demands were met. Tokhtamysh sought to create an anti-Timurid coalition once more, reaching out to the Mamluk sultan Barqūq, the Ottoman sultan Bayezit I, and the Georgian king Giorgi VII. Timur retaliated by invading Georgia. Although he seems to have had troubles with his own emirs in the summer of 1394, that autumn Tokhtamysh was able to raid across the Caucasus into Shirvan. The approach of Timur caused an immediate retreat.[25]

Second Timurid invasion into the Golden Horde and its aftermath

Timur now determined that a second campaign into the Golden Horde was necessary. After some diplomatic dissimulation on both sides, Timur set out with a great army towards Derbent in March 1395. After crossing the pass, Timur's army ravaged the area up to the Terek, where it encountered the forces of Tokhtamysh. After Timur's troops destroyed Tokhtamysh's vanguard, the main battle took place on 15–16 April 1395. Like the battle on the Kondurcha four year earlier, it was a hard-fought engagement between nearly equal forces. Although Timur, who fought like a common warrior, was nearly captured or killed, he once again emerged victorious, after a dissension among Tokhtamysh's emirs. Tokhtamysh fled north to Bolghar and later perhaps to Moldavia. Part of Timur's forces gave chase, catching up with some of the enemy by the Volga and driving them into it; Timur's local allies, led by the Jochid prince Quyurchuq, a son of Urus Khan, advanced on the opposite, left bank of the Volga, to take over the area. Timur probed north, as far as Yelets, before turning to ravaging the cities of the Golden Horde. At Tana, he was happy to receive rich gifts from the Italian merchants before enslaving all Christians and destroying their facilities. Passing though Circassia, he proceeded to pillage and destroy the cities along the Volga, from (old) Astrakhan to Sarai, to Gülistan, in the winter of 1395–1396; the surviving inhabitants were enslaved and "driven like sheep." Timur set out for Samarkand via Derbent in the spring of 1396, laden with plunder and accompanied by herds and captives, including merchants, artists, and craftsmen, leaving the Golden Horde exhausted and pillaged.[26][27]

Tokhtamysh had survived Timur's onslaught, but his position was far more tenuous than before. The ruined capital, Sarai, was in the hands of Timur's protégé Quyurchuq, while the area of Astrakhan and the eastern portions of the Golden Horde were under the control of Tīmūr Qutluq and Edigu, who had joined forces once again. They soon expelled or eliminated Quyurchuq, taking over Sarai in 1396 or 1397, but mollified Timur by assuring him of their submission through an embassy in 1398. Meanwhile, Tokhtamysh had set about reasserting his authority in the southwestern portions of the Golden Horde, killing his cousin Tāsh Tīmūr, who had declared himself khan in the Crimea, and fighting the Genoese there, besieging Kaffa in 1397. In late 1397 or early 1398, Tokhtamysh briefly triumphed over his rivals, taking over Sarai and the Volga towns, and sent out jubilant missives through his envoys all round. But his success was short-lived: Tokhtamysh was defeated in battle by Tīmūr Qutluq and fled first to the Crimea, where he was met with hostility, then via Kiev to Grand Prince Vytautas of Lithuania.[28] Vytautas settled Tokhtamysh and his followers near Vilnius and Trakai, although many of them abandoned him, making their way to the Balkans to enter the service of the Ottoman sultan Bayezit I. Tokhtamysh and Vytautas signed a treaty in which Tokhtamysh confirmed Vytautas as a rightful ruler of Ruthenian lands that were once part of the Golden Horde, and now belonged to Lithuania, and promised him the tribute of the Russian principalities, in exchange for military assistance to recover his throne. Possibly the treaty still stipulated that Vytautas would pay tribute from these the Ruthenian lands once the khan regained his throne. Vytautas was possibly planning to establish himself as overlord in the lands of the Golden Horde.[29]

Exile

Tīmūr Qutluq sent an envoy to demand Tokhtamysh's extradition from Lithuania, but received an ominous answer from Vytautas: "I will not give up Tsar Tokhtamysh, but wish to meet Tsar Temir-Kutlu in person."[30] Vytautas and Tokhtamysh prepared their Lithuanian and Mongol forces for a joint campaign, supported by Polish volunteers under Spytek of Melsztyn. In the summer of 1399, Vytautas and Tokhtamysh set out against Tīmūr Qutluq and Edigu with a large army. On the Vorskla River they encountered the forces of Tīmūr Qutluq, who opened negotiations, intending to delay the engagement until Edigu could arrive with reinforcements. In the process, Tīmūr Qutluq pretended to agree to submit to Vytautas and pay him annual tribute but requested a three-day delay to consider Vytautas' further demands. This was sufficient for Edigu to arrive with his reinforcements. Edigu could not resist the temptation to bandy words with the Lithuanian ruler himself, and arranged a meeting, separated by the course of the river. Further negotiations having proven pointless, the two forces engaged in the Battle of the Vorskla River on 12 August 1399. Using a feigned retreat tactic, Tīmūr Qutluq and Edigu were able to envelop the forces of Vytautas and Tokhtamysh, inflicting a serious defeat on them. Tokhtamysh fled the battlefield and made his way east to Sibir; Vytautas survived the battle, although some twenty princes, including two of his cousins fell in the fight.[31] The defeat was disastrous, ending Vytautas' ambitious policy in the Pontic steppes.[32]

Death

Reduced to the position of an adventurer, Tokhtamysh made his way across the territory of the Golden Horde to its peripheral Siberian possessions. Here he succeeded in bringing parts of the area under his control in 1400, and by 1405 was attempting to ingratiate himself with his protector-turned-enemy, Timur, who had just quarreled with Edigu. Timur's death in February 1405 made any rapprochement moot. Throughout this period, Tokhtamysh naturally attracted the hostility of Edigu and his new puppet khan, Shādī Beg. Edigu is said to have fought Tokhtamysh on sixteen separate occasions between 1400 and 1406; in the final instance, after a reverse at the hands of Tokhtamysh, Edigu spread a rumor about his own death to draw Tokhtamysh out into the open and have him killed in a hail of darts and spears, late in 1406 (or early in 1407), near Tyumen. Khan Shādī Beg apparently claimed or was given credit for the death of Tokhtamysh, while others credited Edigu or Edigu's son Nūr ad-Dīn.[33]

Legacy

When he reunified the Golden Horde in 1380–1381, Tokhtamysh promised to revitalize and stabilize it after two decades of chronic civil war. He was the last khan of the Golden Horde who minted coins with Mongolian script. His sack of Moscow in 1382 undid the setback suffered by the Golden Horde in its domination over the Russian principalities at the Battle of Kulikovo two years earlier. Finally, the invasion of Azerbaijan followed in the path of the aspirations of earlier khans for the exploitation or conquest of that region. In 1385, Tokhtamysh was at the height of his power and his future, and that of the Golden Horde, looked bright.

However, in entering into and exacerbating the conflict with his former protector Timur, Tokhtamysh set a course for the undoing of all his achievements and for his own destruction. Seeking allies, after he had weakened Moscow, he strengthened it with the concession of making the Grand Principality of Vladimir a hereditary possession of the Prince of Moscow in 1389, and by allowing it to take over Nižnij Novgorod in 1393.[34] Similarly, he helped Lithuania establish a precedent for involving itself in the government and politics of the Golden Horde, and making and unmaking khans, several of them Tokhtamysh's sons, for decades to come.[35] Neither of these alliances saved Tokhtamysh, whose authority was dealt severe setbacks by the two great invasions of Timur into the core territories of the Golden Horde in 1391 and 1395–1396. These left Tokhtamysh competing with rival khans, ultimately driving him out definitively, and hounding him to his death in Sibir in 1406. Tokhtamysh's relative solidification of the khan's authority survived him only briefly, and largely due to the influence of his nemesis Edigu; but after 1411 it gave way to another long period of civil war that ended in the disintegration of the Golden Horde. Moreover, Timur's destruction of the Golden Horde's main urban centers, as well as the Italian colony of Tana, dealt a severe and lasting blow to the trade-based economy of the polity, with various negative implications for its future prospects for prosperity and survival.[36]

Tokhtamysh's Siege of Moscow in 1382

Tokhtamysh's Siege of Moscow in 1382 Muscovites gather during the Siege of Moscow

Muscovites gather during the Siege of Moscow Warriors of the Golden Horde attack Moscow.

Warriors of the Golden Horde attack Moscow. Muscovites prepare for the Siege of Moscow

Muscovites prepare for the Siege of Moscow

Family

Among others, Tokhtamysh had married the widow of Mamai, probably identical with a daughter of Berdi Beg and with the Tulun Beg Khanum who had briefly ruled at Sarai in 1370–1371; in 1386 he had her executed, apparently for participating in an obscure conspiracy.[37] According to the Muʿizz al-ansāb, Tokhtamysh had eight sons and five daughters, as well as six grandchildren, as follows.[38]

- Jalāl ad-Dīn (1380–1412) (by Ṭaghāy-Bīka), Khan of the Golden Horde 1411–1412

- Abū-Saʿīd

- Amān Beg

- Karīm Berdi, Khan of the Golden Horde 1409, 1412–1413, 1414 (d. 1417?)

- Sayyid Aḥmad, possibly Khan of the Golden Horde 1416–1417 (he is distinct from Sayyid Aḥmad, Khan 1432–1459)[39]

- Kebek, Khan of the Golden Horde 1413–1414

- Chaghatāy-Sulṭān

- Sarāy-Mulk

- Shīrīn-Bīka

- Jabbār Berdi, Khan of the Golden Horde 1414–1415, 1416–1417

- Qādir Berdi (by a Circassian concubine), Khan of the Golden Horde 1419

- Abū-Saʿīd

- Iskandar (by Ūrun-Bikā)

- Kūchuk Muḥammad (by Ūrun-Bikā) (he is distinct from Küchük Muḥammad, Khan 1434–1459)

- Malika (by Ṭaghāy-Bīka)

- Jānika (by Ṭaghāy-Bīka), who married Edigu

- Saʿīd-Bīka (by Ṭaghāy-Bīka)

- Bakhtī-Bīka (by Shukr-Bīka-Āghā)

- Mayram-Bīka (by Ūrun-Bikā)

Genealogy

- Genghis Khan

- Jochi

- Tuqa-Timur

- Saricha

- Kuyunchak

- Qutluq Khwaja

- Tuy Khwaja

- Tokhtamysh

Notes

- The spelling of Tokhtamysh varies, but the most common spelling is Tokhtamysh. Tokhtamısh, Toqtamysh, Toqtamış, Toqtamıs, Toktamys, Tuqtamış, and variants also appear.

References

- For the color references to the right (west) and left (east) wings of the Ulus of Jochi (later dubbed "Golden Horde" in Russian sources), see for example May 2018: 282-283; in the more relevant Turkic sources the White Horde is the right (west) wing and the Blue Horde is the left (east) wing, opposite to the practice still dominating English-language historiography.

- Denis Sinor. Inner Asia. // Ural and Altaic Series, vol. 96. Bloomington: Indiana University Publications, 1969. P. 181.

- Allen, W. E. D. (5 July 2017). Russian Embassies to the Georgian Kings, 1589–1605: Volumes I and II. Routledge. ISBN 9781317060390.

- Gaev 2002: 53; Sagdeeva 2005: 71; Jackson 2005: 369; Sabitov 2008: 286; Seleznëv 2009: 182; Počekaev 2010: 155, 372; May 2018: 364; for the primary sources, see Vohidov 2006: 46 and Tizengauzen 2006: 436.

- Tizengauzen 2006: 261.

- E.g., Howorth 1880: 222, 225-226; Grousset 1970: 406, 435; Bosworth 1996: 252.

- Howorth 1880: 221-222; Grousset 1970: 406; Seleznëv 2009: 182; Počekaev 2010: 156.

- Počekaev 2010: 156-157.

- Howorth 1880: 222-223; Grousset 1970: 406, 435; Seleznëv 2009: 182; Počekaev 2010: 157-159.

- Howorth 1880: 224; Grousset 1970: 406-407, 435-436; Seleznëv 2009: 182; Počekaev 2010: 159.

- Howorth 1880: 216, 226; Grousset 1970: 407, 436; Seleznëv 2009: 182-183; Počekaev 2010: 160-161.

- Grousset 1970: 407, 436; Počekaev 2010: 161.

- Howorth 1880: 226; Grousset 1970: 407; Seleznëv 2009: 184; Počekaev 2010: 162.

- Howorth 1880: 226-228; Grousset 1970: 407, 436; Halperin 1987: 56; Seleznëv 2009: 183; Počekaev 2010: 163-164.

- Howorth 1880: 228-232, 238; Halperin 1987: 57.

- Howorth 1880: 249-250; Halperin 1987: 57; Seleznëv 2009: 184.

- Počekaev 2010: 164.

- The Turco-Mongol Invasions IV, Medieval Armenian History, Turkish History, Turkey

- Howorth 1880: 233-236; Grousset 1970: 437-438; Seleznëv 2009: 183; Počekaev 2010: 165-166 places Tokhtamysh's first invasion of Azerbaijan in 1386.

- Howorth 1880: 236-239; Grousset 1970: 438; Seleznëv 2009: 183; Počekaev 2010; 166-170.

- Howorth 1880: 239-248; Grousset 1970: 438-440; Seleznëv 2009: 183-184; Počekaev 2010: 170-171.

- Gaev 2002: 54; Vohidov 2006: 46; Počekaev 2010: 171.

- May 2018: 307.

- Howorth 1880: 248-249; Grousset 1970: 440; Seleznëv 2009: 184; Počekaev 2010: 171-172.

- Howorth 1880: 250-251; Grousset 1970: 440-441; Seleznëv 2009: 184; Počekaev 2010: 172-173.

- Howorth 1880: 251-258; Grousset 1970: 441-442; Jackson 2005: 216; Počekaev 2010: 173-174.

- Martin, Janet (2007-12-06). Medieval Russia, 980-1584. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521859165.

- Seleznëv 2009: 184-185.

- Howorth 1880: 258-261; Jackson 2005: 218; Počekaev 2010: 174-175; Kołodziejczyk 2011: 6–8.

- Seleznëv 2009: 175, 185.

- Howorth 1880: 261-262; Seleznëv 2009: 175, 185; Počekaev 2010: 175-176; Frost 2015: 86; the casualties included the princes Andrej of Polock and Dmitrij of Brjansk, as well as the Polish lord Spytek of Melsztyn.

- Jackson 2005: 218-220; Kołodziejczyk 2011: 8.

- Howorth 1880: 262; Grousset 1970: 443; Seleznëv 2009: 185; Počekaev 2010: 176-177.

- Halperin 1987: 57.

- Jackson 2005: 218-220.

- May 2018: 308.

- Počekaev 2010: 165.

- Vohidov 2006: 45-46; the Tawārīḫ-i guzīdah-i nuṣrat-nāmah generally agrees, but places Sayyid Aḥmad correctly as the son of Karīm Berdi and gives variant names for two of the daughters: Tizengauzen 2006: 435; Sabitov 2008: 55-56.

- Identification with the khan of 1416–1417 by Sabitov 2008: 55-56, 288, and Reva 2016: 715; but the khan of 1416–1417 is also plausibly identifiable as a son of Mamkī, son of Minkasar, and thus cousin of Chekre Khan and uncle of Darwīsh Khan, according to Počekaev 2010: 194, 366, 372.

Bibliography

- Allen, W. E. D., Russian Embassies to the Georgian Kings, 1589-1605, 2 vols., Cambridge, 1970.

- Frost, Robert (2015). The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania. The Making of the Polish-Lithuanian Union, 1385—1569. Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-820869-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gaev, A. G., "Genealogija i hronologija Džučidov," Numizmatičeskij sbornik 3 (2002) 9-55.

- Grousset, R., The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia, New Brunswick, NJ, 1970.

- Halperin, D., Russia and the Golden Horde, Bloomington, 1987.

- Howorth, H. H., History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century. Part II.1. London, 1880.

- Jackson, P., The Mongols and the West, 1221–1410, London, 2005.

- Kołodziejczyk, Dariusz (2011). The Crimean Khanate and Poland-Lithuania: International Diplomacy on the European Periphery (15th-18th Century). A Study of Peace Treaties Followed by Annotated Documents. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004191907.

- Martin, J., Medieval Russia 980–1584 (2nd ed.), Cambridge, 2007.

- May, T., The Mongol Empire. Edinburgh, 2018.

- Počekaev, R. J., Cari ordynskie: Biografii hanov i pravitelej Zolotoj Ordy. Saint Petersburg, 2010.

- Reva, R., "Borba za vlast' v pervoj polovine XV v.," in Zolotaja Orda v mirovoj istorii, Kazan', 2016: 704-729.

- Sabitov, Ž. M., Genealogija "Tore", Astana, 2008.

- Seleznëv, J. V., Èlita Zolotoj Ordy: Naučno-spravočnoe izdanie, Kazan', 2009.

- Sinor, D., Inner Asia, Bloomington, 1969.

- Tizengauzen, V. G. (trans.), Sbornik materialov otnosjaščihsja k istorii Zolotoj Ordy. Izvlečenija iz persidskih sočinenii, republished as Istorija Kazahstana v persidskih istočnikah. 4. Almaty, 2006.

- Vohidov, Š. H. (trans.), Istorija Kazahstana v persidskih istočnikah. 3. Muʿizz al-ansāb. Almaty, 2006.