2017 Atlantic hurricane season

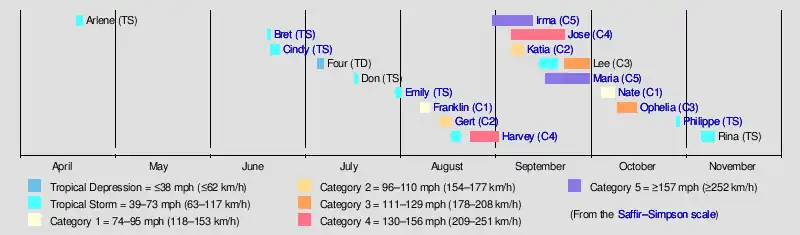

The 2017 Atlantic hurricane season was a devastating, extremely active Atlantic hurricane season and the costliest on record, with a damage total of at least $294.92 billion (USD).[nb 1] The season featured 17 named storms, 10 hurricanes, and 6 major hurricanes.[nb 2] Most of the season's damage was due to hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria. Another notable hurricane, Nate, was the worst natural disaster in Costa Rican history. These four storm names were retired following the season due to the number of deaths and amount of damage they caused.

| 2017 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | April 19, 2017 |

| Last system dissipated | November 9, 2017 |

| Strongest storm | |

| By maximum sustained winds | Irma |

| • Maximum winds | 180 mph (285 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 914 mbar (hPa; 26.99 inHg) |

| By central pressure | Maria |

| • Maximum winds | 175 mph (280 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 908 mbar (hPa; 26.81 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 18 |

| Total storms | 17 |

| Hurricanes | 10 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 6 |

| Total fatalities | 3,369 total |

| Total damage | ≥ $294.803 billion (2017 USD) (Costliest tropical cyclone season on record) |

| Related articles | |

Collectively, the tropical cyclones were responsible for at least 3,364 deaths—the most fatalities in a single season since 2005. The season also had the highest accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) since 2005 with an approximate index of 224 units, with a record three hurricanes each generating an ACE of over 40: Irma, Jose, and Maria.

This season featured two Category 5 hurricanes (one of only seven on record to feature multiple Category 5 hurricanes), and the only season other than 2007 with two hurricanes making landfall at that intensity. The season's ten hurricanes occurred one after the other, the greatest number of consecutive hurricanes in the satellite era, and tied for the highest number of consecutive hurricanes ever observed in the Atlantic basin.

The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30. These dates historically describe the period of year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin and are adopted by convention. However, as shown by Tropical Storm Arlene in April, the formation of tropical cyclones was possible at other times of the year. In late August, Hurricane Harvey struck Texas and became the first major hurricane to make landfall in the United States since Wilma in 2005, ending the 12-year US Major Hurricane drought and the strongest since Charley in 2004. The storm tied the record for the costliest tropical cyclone and broke the record for most rainfall dropped by a tropical cyclone in the United States, with extreme flooding in the Houston area. In early September, Hurricane Irma became the first Category 5 hurricane to impact the northern Leeward Islands on record, later making landfall in the Florida Keys as a Category 4 hurricane. In terms of sustained winds, Irma, at the time, became the strongest hurricane ever recorded in the Atlantic basin outside of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, with maximum sustained winds of 180 mph (285 km/h); it was later surpassed in 2019 by Hurricane Dorian. In mid September, Hurricane Maria became the first Category 5 hurricane in history to strike the island of Dominica. It later made landfall in Puerto Rico as a high-end Category 4 hurricane with catastrophic effect. Most of the deaths from this season occurred from Maria. In early October, Hurricane Nate became the fastest-moving tropical cyclone in the Gulf of Mexico on record and the third hurricane to strike the contiguous United States in 2017. Slightly over a week later, Hurricane Ophelia became the easternmost major hurricane in the Atlantic basin on record, and later impacted most of northern Europe as an extratropical cyclone. The season concluded with Tropical Storm Rina, which became extratropical on November 9.

Initial predictions for the season anticipated that an El Niño would develop, lowering tropical cyclone activity. However, the predicted El Niño failed to develop, with cool-neutral conditions developing instead, later progressing to a La Niña—the second one in a row. This led forecasters to raise their predicted totals in late May, with some later anticipating that the season could be the most active since 2010.

Prior to the start of this season, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) changed its policy to permit issuance of advisories on disturbances that were not yet tropical cyclones but had a high chance to become one, and were expected to bring tropical storm or hurricane conditions to landmasses within 48 hours. As a result of this change, early watches and warnings could be issued by local authorities. Such systems would be termed "potential tropical cyclones".[2] The first storm to receive this designation was Potential Tropical Cyclone Two, which later developed into Tropical Storm Bret, east-southeast of the Windward Islands on June 18.[3] Additionally, the number assigned to a potential tropical cyclone would remain with that disturbance, meaning that the next identified tropical system would be designated with the following number, even if the potential tropical cyclone did not develop into one. The first such system was Potential Tropical Cyclone Ten in August.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes | |

| Average (1981–2010[4]) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | ||

| Record high activity[5] | 30 | 15 | 7† | ||

| Record low activity[5] | 1 | 0† | 0† | ||

| TSR[6] | December 13, 2016 | 14 | 6 | 3 | |

| TSR[7] | April 5, 2017 | 11 | 4 | 2 | |

| CSU[8] | April 6, 2017 | 11 | 4 | 2 | |

| TWC[9] | April 17, 2017 | 12 | 6 | 2 | |

| NCSU[10] | April 18, 2017 | 11–15 | 4–6 | 1–3 | |

| TWC[11] | May 20, 2017 | 14 | 7 | 3 | |

| NOAA[12] | May 25, 2017 | 11–17 | 5–9 | 2–4 | |

| TSR[13] | May 26, 2017 | 14 | 6 | 3 | |

| CSU[14] | June 1, 2017 | 14 | 6 | 2 | |

| UKMO[15] | June 1, 2017 | 13* | 8* | N/A | |

| TSR[16] | July 4, 2017 | 17 | 7 | 3 | |

| CSU[17] | July 5, 2017 | 15 | 8 | 3 | |

| CSU[18] | August 4, 2017 | 16 | 8 | 3 | |

| TSR[19] | August 4, 2017 | 17 | 7 | 3 | |

| NOAA[20] | August 9, 2017 | 14–19 | 5–9 | 2–5 | |

| Actual activity | 17 | 10 | 6 | ||

| * June–November only, Longest: January–November. † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

Ahead of and during the season, several national meteorological services and scientific agencies forecast how many named storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes will form during a season, and/or how many tropical cyclones will affect a particular country. These agencies include the Tropical Storm Risk (TSR) Consortium of the University College London, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Colorado State University (CSU). The forecasts include weekly and monthly changes in significant factors that help determine the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a particular year.[6] Some of these forecasts also take into consideration what happened in previous seasons and the dissipation of the 2014–16 El Niño event. On average, an Atlantic hurricane season between 1981 and 2010 contained twelve tropical storms, six hurricanes, and two major hurricanes, with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index of between 66 and 103 units.[4] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of a hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed; therefore, long-lived storms and particularly strong systems result in high levels of ACE. The measure is calculated at full advisories for cyclones at tropical storm strength—storms with winds in excess of 39 mph (63 km/h).[21]

Pre-season outlooks

The first forecast for the year was issued by TSR on December 13, 2016.[6] They anticipated that the 2017 season would be a near-average season, with a prediction of 14 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes. They also predicted an ACE index of around 101 units.[6] On December 14, CSU released a qualitative discussion detailing five possible scenarios for the 2017 season, taking into account the state of the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation and the possibility of El Niño developing during the season.[22] TSR lowered their forecast numbers on April 5, 2017, to 11 named storms, 4 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes, based on recent trends favoring the development of El Niño.[7] The next day, CSU released their prediction, also predicting a total of 11 named storms, 4 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes.[8] On April 17, The Weather Channel (TWC) released their forecasts, calling for 2017 to be a near-average season, with a total of 12 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes.[9] The next day, on April 18, North Carolina State University released their prediction, also predicting a near-average season, with a total of 11–15 named storms, 4–6 hurricanes, and 1–3 major hurricanes.[10] On May 20, TWC issued an updated forecast, raising their numbers to 14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes to account for Tropical Storm Arlene as well as the decreasing chance of El Niño forming during the season.[11] On May 25, NOAA released their prediction, citing a 70% chance of an above average season due to "a weak or nonexistent El Niño", calling for 11–17 named storms, 5–9 hurricanes, and 2–4 major hurricanes.[12] On May 26, TSR updated its prediction to around the same numbers as its December 2016 prediction, with only a minor change in the expected ACE index amount to 98 units.[13]

Mid-season outlooks

CSU updated their forecast on June 1 to include 14 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes, to include Tropical Storm Arlene.[14] It was based on the current status of the North Atlantic oscillation, which was showing signs of leaning towards a negative phase, favoring a warmer tropical Atlantic; and the chances of El Niño forming were significantly lower. However, they stressed on the uncertainty that the El Niño–Southern Oscillation could be in a warm-neutral phase or weak El Niño conditions by the peak of the season.[14] On the same day, the United Kingdom Met Office (UKMO) released its forecast of a very slightly above-average season. It predicted 13 named storms, with a 70% chance that the number would be in the range between 10 and 16, and 8 hurricanes, with a 70% chance that the number would be in the range between 6 and 10. It also predicted an ACE index of 145, with a 70% chance that the index would be between 92 and 198.[15] On July 4, TSR released their fourth forecast for the season, increasing their predicted numbers to 17 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes, due to the fact that El Niño conditions would no longer develop by the peak of the season and the warming of sea-surface temperatures across the basin. Additionally, they predicted a revised ACE index of 116 units.[16] During August 9, NOAA released their final outlook for the season, raising their predictions to 14–19 named storms, though retaining 5–9 hurricanes and 2–5 major hurricanes. They also stated that the season had the potential to be extremely active, possibly the most active since 2010.[20]

Seasonal summary

| Rank | Season | ACE value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1933 | 258.6 |

| 2 | 2005 | 245.3 |

| 3 | 1893 | 231.1 |

| 4 | 1926 | 229.6 |

| 5 | 1995 | 227.1 |

| 6 | 2004 | 226.9 |

| 7 | 2017 | 224.9 |

| 8 | 1950 | 211.3 |

| 9 | 1961 | 188.9 |

| 10 | 1998 | 181.8 |

| (source) | ||

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1, 2017.[25] Among the busiest on record, the season produced eighteen tropical depressions, all of which but one of which further intensified into tropical storms. Ten hurricanes occurred in succession, the greatest number of consecutive hurricanes since the start of the satellite era in 1966; six of these further strengthened into major hurricanes.[26] The season had the most named storms and hurricanes, along with most major hurricanes, since 2005. It also produced the first major hurricanes to strike the continental U.S. since 2005.[27]

Unlike the pattern of previous years that acted to steer many tropical cyclones harmlessly into the open Atlantic, 2017 featured a pattern conducive for landfalls;[26] in fact, the season culminated into 23 separate landfalls by Atlantic named storms.[28] At least 3,364 fatalities were recorded and damage totaled $294.92 billion,[29] cementing the 2017 season as the costliest in recorded history and the deadliest season since 2005.[30]

The extremely active season came to fruition through a multitude of different factors. Pre-season projections noted the potential for a weak to moderate El Niño event to evolve through the summer and fall on the basis of statistical model guidance. Instead, equatorial Pacific Ocean temperatures began cooling throughout the summer, reaching La Niña threshold in November and curtailing the negative effects on Atlantic hurricane activity originally expected. In addition, tropical Atlantic Ocean temperatures—previously below average in months prior to the start of the season—underwent rapid warming by late May, providing lower sea level pressures, weaker trade winds, increased mid-level moisture, and all-around a more conducive environment for above-average activity.[26]

Early/pre-season activity

The season's first tropical cyclone, Arlene, developed on April 19, becoming only the second April tropical storm on record.[31] Above-average activity continued throughout June and July with the formations of tropical storms Bret, Cindy, Don, and Emily, along with Tropical Depression Four. These were, however, mostly weak and short-lived storms.[32]

| Rank | Cost | Season |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≥ $294.803 billion | 2017 |

| 2 | $172.297 billion | 2005 |

| 3 | $120.425 billion | 2022 |

| 4 | ≥ $80.727 billion | 2021 |

| 5 | $72.341 billion | 2012 |

| 6 | $61.148 billion | 2004 |

| 7 | ≥ $51.114 billion | 2020 |

| 8 | ≥ $50.526 billion | 2018 |

| 9 | ≥ $48.855 billion | 2008 |

| 10 | $27.302 billion | 1992 |

August yielded four storms—Franklin, Gert, Harvey, and Irma—all of which intensified into hurricanes.[33] Harvey attained Category 4 status prior to reaching the Texas coastline, ending the record streak of 4,323 days without a major hurricane landfall in the United States;[34] with damage estimates up to $125 billion, Harvey is tied with Hurricane Katrina as the costliest natural disaster on record in the United States.[35][36] Hurricane Irma reached peak winds of 180 mph (285 km/h), making it the strongest Atlantic hurricane outside the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea until surpassed by Hurricane Dorian in 2019.[37] Irma ravaged the northern Leeward Islands and produced a trail of destruction through the Greater Antilles and Southeast United States.[38] Harvey and Irma struck the continental United States as Category 4 hurricanes in the span of two weeks; this marks the first time the country has suffered two landfalls of such intensity during the same hurricane season.[26]

Peak to late-season activity

September featured copious activity, with four hurricanes forming: Jose, Katia, Lee, and Maria,[39] the final of which became the tenth-most-intense Atlantic hurricane on record.[40] As Irma also persisted into September and reached Category 5 intensity, it and Maria marked the first recorded instance of two Category 5 hurricanes occurring in the same month. The season became only the sixth to feature at least two Category 5 hurricanes, after 1932, 1933, 1961, 2005, and 2007.[41] With Maria becoming the first Category 5 hurricane on record to strike Dominica,[26] 2017 also became the only season other than 2007 to have at least two cyclones make landfall at Category 5 intensity.[41] Maria caused a major humanitarian crisis in Puerto Rico, resulting in nearly $91 billion in damage and a death toll that exceeded 3,000.[42][43] October featured hurricanes Nate and Ophelia, as well as Tropical Storm Philippe;[44] Nate was the worst natural disaster in Costa Rican history, as well as the fastest-moving cyclone in the Gulf of Mexico. Ophelia became the easternmost major hurricane on record in the Atlantic.[26] Activity concluded with the formation of Tropical Storm Rina in early November,[45] though the season did not officially end until November 30.[25]

The seasonal activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy index value of 225 units, the seventh-highest value on record in the Atlantic. Despite an above average number of storms to begin 2017, many were weak and short-lived, resulting in the lowest ACE value for a season's first five named storms on record.[46] However, Hurricane Irma produced the third-highest ACE value on record, 64.9 units.[47] The season ultimately featured three storms that produced an ACE value above 40 units, the first occurrence on record.[48] September 2017 featured more ACE than any month in recorded history in the Atlantic (surpassing September 2004),[49] and September 8 alone produced more ACE than any other day on record.[26] Overall, September's ACE value represented activity about three-and-a-half times more active than the 1981–2010 average for the month.[39]

Systems

Tropical Storm Arlene

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | April 19 – April 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 990 mbar (hPa) |

A potent extratropical cyclone formed well east of Bermuda on April 16. The cyclone moved southeast, becoming disconnected from the surrounding environment and gradually losing its frontal characteristics. Deep convection formed in bands north and east of the center by 00:00 UTC, and gradually on April 19, leading to the formation of a subtropical depression. Despite an unfavorable environment, with ocean temperatures near 68 °F (20 °C) and moderate wind shear, convection coalesced near the center and allowed the subtropical depression to become fully tropical by 00:00 UTC on April 20. It intensified into Tropical Storm Arlene six hours later. After attaining peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) early on April 21, the storm began to revolve counterclockwise around a larger extratropical low. The storm tracked into the cold sector of the cyclone, causing Arlene to lose tropical characteristics around 12:00 UTC on April 21. The post-tropical cyclone moved south and east, before dissipating well west-southwest of the Azores on April 22.[31]

Tropical Storm Bret

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 19 – June 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A low-latitude tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on June 13. Initially accompanied by a large area of convection, the showers and thunderstorms quickly diminished by later that day. After an increase in shower and thunderstorm activity later on, as well as the development of a well-defined circulation, the system was classified as Tropical Storm Bret while located about 185 mi (298 km) east-southeast of Trinidad at 18:00 UTC on June 19. Bret intensified slightly further, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) around 02:00 UTC the following day. Simultaneously, the storm made landfall in southwestern Trinidad. After briefly emerging in the Caribbean, Bret made another landfall on the Paria Peninsula of Venezuela around 09:00 UTC on June 20. Increasing wind shear, the storm's relatively fast forward speed, and land interaction caused Bret to dissipate about three hours later.[50] The remnants later contributed to the formation of Hurricane Dora in the eastern Pacific.[51]

In Trinidad, Bret produced sustained winds of 48 mph (77 km/h) and gusts up to 71 mph (114 km/h) at Guayaguayare. Nearly 100 homes on the island suffered roof damage. Winds also downed some utility poles, causing power outages. With precipitation peaking at 4.76 in (121 mm) in Penal, several towns in southern and central Trinidad were flooded. One person on the island died after he slipped and fell while running across a makeshift bridge; the fatality is considered indirectly related to Bret.[50] On the island of Tobago, a man's house collapsed on him; he eventually succumbed to his injuries a week later.[52] In Venezuela, mudslides damaged or destroyed a number of homes on Margarita Island.[50] On the mainland, about 800 families were significantly affected in Miranda state, of whom 400 lost their homes.[53]

Tropical Storm Cindy

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 20 – June 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 991 mbar (hPa) |

In mid-June, two tropical waves and an area of disturbed weather began merging over the western Caribbean Sea. A broad area of low pressure developed on June 19, and by 18:00 UTC on the following day, Tropical Storm Cindy formed over the central Gulf of Mexico about 240 mi (390 km) south-southwest of the mouth of the Mississippi River. While slowly moving to the northwest, Cindy's intensification was slow due to the effects of dry air and moderate to strong wind shear. After peaking with sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) on June 21, Cindy weakened slightly prior to making landfall in Louisiana just east of Sabine Pass on June 22. The storm quickly weakened after moving inland and degenerated into a remnant low on June 23, dissipating over the Mid-Atlantic on the following day.[54]

Upon making landfall in Louisiana, the storm generated a peak storm surge of 4.1 ft (1.2 m) and tides up to 6.38 ft (1.94 m) above normal in Vermilion Parish. However, coastal flooding mainly consisted of roads being inundated, while some beach erosion occurred.[55] Due to Cindy's weak nature, only a few locations observed sustained tropical storm force winds. Consequently, wind damage was generally minor. Because the cyclone had an asymmetrical structure, heavy rainfall was observed over southeastern Mississippi, southwestern Alabama, and the far western Florida Panhandle, while lesser precipitation amounts fell over Louisiana and Texas. The storm and its remnants spawned 18 tornadoes throughout the eastern United States, which caused just over $1.1 million in damage. Overall, damage from Cindy totaled less than $25 million. Three fatalities were attributed to the cyclone, one in Alabama after a boy was struck by a log pushed by waves,[54] another in Texas due to drowning,[56] and a third in Tennessee after a motorist skidded off a road and crashed into a pole.[57]

Tropical Depression Four

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 5 – July 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min); 1009 mbar (hPa) |

Early on June 29, the NHC began tracking a tropical wave embedded within a large envelope of deep moisture across the coastline of western Africa.[58] The wave emerged into the Atlantic on July 1.[59] The disturbance was introduced as a potential contender for tropical cyclone formation two days later, as environmental conditions were expected to favor slow organization.[60] It began to show signs of organization over the central Atlantic early on July 3,[59] but the chances for development began to decrease two days later as the system moved toward a more stable environment.[61] After the wave developed a well-defined circulation and a persistent mass of deep convection, Tropical Depression Four formed at 18:00 UTC on July 5, while situated about 1,545 mi (2,485 km) east of the Lesser Antilles. The depression struggled to intensify due to a dry environment caused by a Saharan Air Layer to its east, causing the low-level circulation to weaken. After much of the convection diminished, the depression degenerated into a tropical wave late on July 7.[59]

Tropical Storm Don

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 17 – July 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

Late on July 15, the NHC highlighted a low-pressure trough over the central Atlantic as having the potential to develop into a tropical cyclone in the coming days.[62] The disturbance began to show signs of organization early on July 17,[63] and a tropical depression formed at 06:00 UTC that day. The system continued to intensify, and developed into Tropical Storm Don just six hours later.[64] The storm's overall appearance improved over subsequent hours up until around 00:00 UTC, as a central dense overcast, accompanied by significant clusters of lightning, became pronounced.[65] Don attained its peak intensity at this time, characterized by winds of approximately 50 mph (85 km/h) as measured by reconnaissance aircraft.[64] The next plane to investigate the cyclone a few hours later, however, found that the system's center had become less defined, and that sustained wind speeds had decreased to about 40 mph (64 km/h).[66] A combination of reconnaissance data and surface observations from the Windward Islands indicated that Don opened up into a tropical wave around 12:00 UTC on July 18, as it entered the eastern Caribbean Sea.[64]

Tropical Storm Emily

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 30 – August 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1001 mbar (hPa) |

In late July, a dissipating cold front extended into the northeastern Gulf of Mexico, where the NHC began forecasting the development of an area of low pressure over the next day on July 30. Despite having a low chance of development, a rapid period of organization occurred over the next 24 hours. Tropical Depression Six developed at 18:00 UTC on July 30 about 165 mi (266 km) west-northwest of St. Petersburg, Florida. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Emily early the following day. The storm then peaked with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,001 mbar (29.6 inHg). Around 14:45 UTC, Emily made landfall on Longboat Key. Weakening quickly ensued, and later that day the circulation of Emily became elongated as it was downgraded to a tropical depression. The increasingly disrupted system later moved off the First Coast of Florida into the western Atlantic early the next day, accelerating northeastwards before degenerating into a remnant low early on August 2.[67]

Following the classification of Tropical Storm Emily, Florida Governor Rick Scott declared a state of emergency for 31 counties to ensure residents were provided with the necessary resources.[68] Heavy rainfall produced by Emily caused widespread flooding in Polk and Pinellas counties, prompting the closure of roads and evacuation of a few homes. Coastal flooding was reported in Hillsborough, Manatee, Sarasota, Lee, and Collier counties, causing additional road closures.[67] An EF0 tornado touched down Bradenton, destroying two barns and multiple greenhouses as well as collapsing an engineered wall.[69] The storm indirectly led to flooding in Miami and Miami Beach, where 6.97 in (177 mm) of rain fell in 3.5 hours, of which 2.17 in (55 mm) fell in just 30 minutes.[70] Total damage from Emily was estimated to be near US$10 million.[67]

Hurricane Franklin

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 7 – August 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 981 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on July 27. After reaching the eastern Caribbean on August 3, convection began increasing. The disturbance became Tropical Storm Franklin at 00:00 UTC on August 7, about 85 mi (137 km) north-northeast of Cabo Gracias a Dios. After strengthening steadily, Franklin made its first landfall near Pulticub, Quintana Roo, with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) at 03:45 UTC on August 8.[71] The cyclone weakened considerably while over the Yucatán Peninsula, however its satellite presentation remained well-defined, with the inner core tightening up considerably.[72] Later that day, Franklin emerged into the Bay of Campeche, and immediately began strengthening again, becoming a hurricane late on August 9. The system peaked with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h) and a pressure of 981 mbar (28.97 inHg) around 00:00 UTC the next day. About five hours later, Franklin made landfall in Vega de Alatorre, Veracruz. The storm rapidly weakened thereafter, and by 18:00 UTC on August 10, it dissipated as a tropical cyclone.[71] However, its mid-level circulation remained intact and later contributed to the formation of Tropical Storm Jova in the Eastern Pacific early on August 12.[73]

Immediately upon classification of Franklin as a potential tropical cyclone, tropical storm warnings were issued for much of the eastern side of the Yucatán Peninsula on August 6;[71] a small portion of the coastline was upgraded to a hurricane watch with the possibility of Franklin nearing hurricane intensity as it approached the coastline the next night. Approximately 330 people were reported as going into storm shelters, and around 2,200 people relocated from the islands near the coastline to farther inland in advance of the storm.[74] Some areas of Belize received up to 12 in (0.30 m) of rain, though little damage occurred.[75] In the Mexican part of Yucatán Peninsula, damage was reported as having been minimal.[74] Near the storm's second landfall location, precipitation peaked at 16.14 in (410 mm) in Las Vigas de Ramírez, Veracruz, while two other observation sites recorded nearly 13 in (330 mm) of rain. Strong winds downed trees and power lines, in addition to damaging homes and crops. Heavy rains flooded some rivers and caused a few landslides.[76] Damage totaled about $15 million.[77]

Hurricane Gert

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 12 – August 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); 962 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on August 3. Although environmental conditions were favorable, the wave failed to become a tropical cyclone before reaching a less favorable environment. Around August 5, the southern portion of the wave split off and later developed into Hurricane Kenneth over the Eastern Pacific. After progressing into the southwestern Atlantic several days later, the wave encountered more favorable upper-level winds and began to show signs of organization. Following the formation of a well-defined circulation, the disturbance was upgraded to a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on August 12 about 265 mi (426 km) northeast of the Turks and Caicos Islands. By 00:00 UTC the following day, it intensified into Tropical Storm Gert. At 06:00 UTC on August 15, Gert intensified into a Category 1 hurricane. Accelerating east-northeastwards, Gert peaked as a high-end Category 2 system early on August 17 at an unusually high latitude of 40°N. Thereafter, Gert began to rapidly weaken as it moved into sharply cooler waters. Just 18 hours after achieving peak intensity, Gert weakened below hurricane status on August 17 at 12:00 UTC and degenerated to an extratropical cyclone well east of Nova Scotia by 18:00 UTC.[78]

Two people drowned due to strong rip currents produced by the hurricane: one in the Outer Banks of North Carolina and the other in Nantucket, Massachusetts.[79][80] The remnants of Gert merged with another extratropical cyclone that later threatened Ireland and the United Kingdom,[81] sparking Met Éireann to issue yellow weather warnings for the entirety of Ireland.[82] As the storm hit, severe floods occurred in Northern Ireland, with floodwaters reaching 4.9 ft (1.5 m) in height, necessitating the rescue of more than 100 people.[83]

Hurricane Harvey

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 17 – September 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); 937 mbar (hPa) |

Harvey originated from a tropical wave that emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on August 12. While moving westward, convection increased markedly on August 15, with a low-pressure center forming early the following day. Wind shear initially prevented further development, though the wave became a tropical depression around 06:00 UTC on August 17 about 505 mi (813 km) east of Barbados. About 12 hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Harvey. After striking Barbados and Saint Vincent, Harvey entered the Caribbean Sea, where it encountered hostile wind shear. The system weakened to a tropical depression early on August 19 and then degenerated into a tropical wave several hours later. Harvey's remnants continued into the Bay of Campeche, where more conducive environmental conditions led to the re-designation of a tropical depression around 12:00 UTC on August 23, and subsequent intensification into a tropical storm six hours later. The tropical cyclone began a period of rapid intensification shortly thereafter, attaining hurricane intensity by 18:00 UTC on August 24 and Category 4 intensity by 00:00 UTC on August 26.[36]

The hurricane made landfall in Texas between Port Aransas and Port O'Connor around 03:00 UTC on August 26, possessing maximum winds of 130 mph (215 km/h).[36] Harvey was the first major hurricane to strike the United States since Hurricane Wilma on October 24, 2005—a record 4,323-day span[84]—and the first Category 4 hurricane to strike the United States since Charley in 2004, as well as the first Category 4 to make landfall in Texas since Carla in 1961.[85] The storm gradually weakened, falling to tropical storm intensity around 18:00 UTC on August 26 as it drifted across southeastern Texas. A light steering pattern caused the storm to emerge into the Gulf of Mexico on August 28, but wind shear only allowed for slight re-intensification. Harvey turned north-northeastward and struck just west of Cameron, Louisiana, as a weak tropical storm around 08:00 UTC on August 30. The system weakened to a tropical depression over central Louisiana later that day, before losing tropical characteristics over central Tennessee early on September 1. Harvey's extratropical remnants dissipated over northern Kentucky by the next day.[36]

The areas near Harvey's landfall location in Texas experienced extensive wind damage. In Aransas, Nueces, Refugio, and San Patricio counties, the storm destroyed approximately 15,000 homes and damaged another 25,000. Extensive tree damage also occurred.[36] Rockport, Fulton, and the surrounding cities were particularly hard hit.[86] Farther northeast, Harvey dropped very heavy rainfall amounts over Southeast Texas, especially the Greater Houston area. Precipitation peaked at 60.58 in (1,539 mm) in Nederland—the highest-ever rainfall total for any tropical cyclone in the United States.[87] In addition to the flooding, Harvey spawned several tornadoes around Houston.[88] Harvey caused 36 deaths in Harris County alone, with all but three linked to freshwater flooding. In the Greater Houston area, flooding damaged or destroyed more than 300,000 buildings and homes and about 500,000 cars. An additional 110,000 structures were damaged in the counties east of the Houston area. Louisiana also experienced flooding, with water entering about 2,000 homes in Beauregard, Calcasieu, and Cameron parishes. In other states, the storm left relatively minor flooding, some wind damage, and power outages. Estimates place the damage caused by Harvey at $125 billion, which ties it with Hurricane Katrina as the costliest tropical cyclone on record.[36] Harvey killed 108 people, including 107 in the United States[36][89] and one woman in Guyana who died after her house collapsed on her.[90]

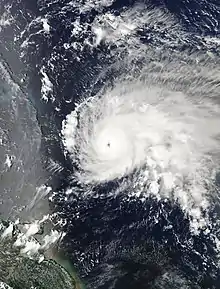

Hurricane Irma

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 30 – September 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 180 mph (285 km/h) (1-min); 914 mbar (hPa) |

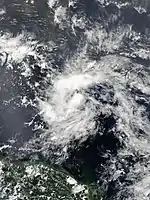

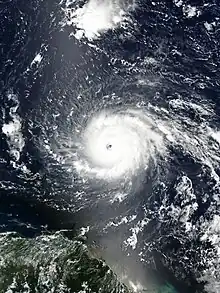

A westward-moving tropical wave developed into a tropical depression about 140 mi (230 km) west-southwest of São Vicente in the Cape Verde Islands at 00:00 UTC on August 30, just six hours before becoming Tropical Storm Irma. Amid an environment of low wind shear and warm ocean temperatures, Irma rapidly strengthened, becoming a hurricane early on August 31 and then a major hurricane less than 24 hours thereafter. After reaching an initial peak with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h), Irma fluctuated in intensity over the next few days due to a combination of drier air and eyewall replacement cycles. However, by September 4, intensification resumed and Irma gained Category 4 status. A reconnaissance aircraft investigating the system east of the Caribbean on September 5 found the cyclone at Category 5 intensity. With a clear eye surrounded by a ring of extremely deep convection, Irma peaked with maximum sustained winds of 180 mph (285 km/h). The storm would maintain Category 5 intensity for the next 60 hours as it moved through the northern Leeward Islands. On September 6, Irma struck Barbuda, Saint Martin, and Virgin Gorda with winds of 180 mph (285 km/h) before moving northwest over the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico.[38]

Some weakening occurred south of the Bahamas, but the cyclone regained Category 5 intensity before making landfall on the Cayo Romano of Cuba at 03:00 UTC on September 9 with winds of 165 mph (270 km/h). Land interaction disrupted the storm temporarily, but once again it strengthened to acquire winds of 130 mph (215 km/h), before making landfall on Cudjoe Key in the Florida Keys early on September 10. A few hours later, it struck Marco Island, Florida, with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). Irma continued north-northwestward across Florida and weakened to a tropical storm over the northern part of the state later that day. The storm steadily weakened over the southeastern United States before losing tropical characteristics in Georgia early on September 12. The remnant low persisted for another day before dissipating over Missouri.[38]

As the storm moved through the northern Leeward Islands, its landfall intensity stands behind the 1935 Labor Day hurricane and 2019's Hurricane Dorian as the strongest landfalling cyclone on record in the Atlantic.[91] The storm devastated several Leeward Islands. On Barbuda, approximately 95% of structures were damaged or destroyed. All Barbudans who stayed during the storm left for Antigua afterwards, leaving the island uninhabited for the first time in 300 years.[38] The French territories of Saint Martin and Saint Barthélemy combined suffered about $4.07 billion in damage and 11 fatalities.[92] In the former, about 90% of homes were damaged, with 60% of those being considered uninhabitable. On Sint Maarten, the Dutch portion of Saint Martin, Irma severely damaged the airport and approximately 70% of structures were damaged or destroyed.[38] Sint Maarten received about $1.5 billion in damage and four deaths occurred there.[93] The British Virgin Islands experienced $3.47 billion in damage and four deaths,[38][94] with numerous buildings and roads destroyed in Tortola. In the United States Virgin Islands (USVI), widespread destruction was reported on Saint Thomas, Saint John, and Saint Croix.[38] The storm's toll in the USVI included four deaths and about $2.4 billion in damage.[95][96]

In Turks and Caicos Islands, Irma wrought significant damage to structures and communication infrastructures. Damage totaled about $500 million. The storm devastated some islands in the Bahamas, especially Great Inagua and Crooked islands, with 70% of homes damaged on the former. In Cuba, the provinces of Camagüey, Ciego de Ávila, and Matanzas were hardest hit. Irma damaged over 150,000 homes in Cuba, with almost 15,000 totally destroyed.[38] A total of 10 deaths occurred and damage was estimated at $13.6 billion.[97][98] In Florida, the storm damaged numerous homes and businesses, including more than 65,000 structures in the west-central and southwestern portions of the state alone.[99] Approximately 50,000 boats were damaged or destroyed.[100] At the height of the storm, more than 6.7 million electrical customers were without power.[101] The storm also left flooding along at least 32 rivers and creeks, especially the St. Johns River and its tributaries.[102] At least 84 deaths occurred in the state and damage was estimated at $50 billion. In other states, such as Georgia and South Carolina, Irma left some wind damage, tornadoes, and coastal flooding. Irma resulted in at least 92 deaths in the United States.[38]

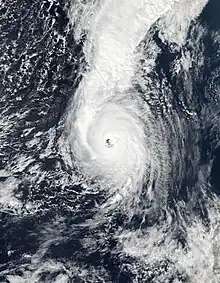

Hurricane Jose

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 5 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-min); 938 mbar (hPa) |

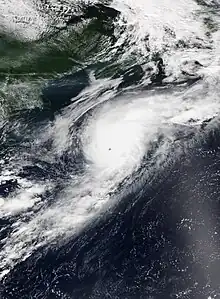

A westward-moving tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa on August 31, organizing into Tropical Storm Jose over the open eastern Atlantic by 15:00 UTC on September 5. Low wind shear and warm sea-surface temperatures allowing Jose to quickly strengthen, attaining hurricane intensity late on September 6 and reaching major hurricane status late on September 7. Around 00:00 UTC on September 9, Jose peaked as a strong Category 4 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 155 mph (250 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 938 mbar (27.7 inHg), on the cusp of reaching Category 5 status. Thereafter, northerly wind shear, drier air, and upwelled seas ushered in a weakening trend of the storm. A large mid-latitude low-pressure area offshore Atlantic Canada and the circulation associated with Hurricane Irma resulted in the collapse of steering currents, causing Jose to decelerate and execute a cyclonic loop.[103]

While executing the cyclonic loop, Jose briefly weakened to a tropical storm early on September 15, before re-intensifying into a hurricane about 18 hours later. By September 16, the system curved northward along the western periphery of a central Atlantic ridge. Remaining well offshore the East Coast of the United States, Jose re-intensified slightly further, attaining a secondary peak intensity as a high-end Category 1 hurricane with winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) around 12:00 UTC on September 17. After passing north of the Gulf Stream, the cyclone encountered colder ocean temperatures and increasing wind shear, causing it to weaken to a tropical storm by 12:00 UTC on September 19. Around that time, the storm began acquiring extratropical characteristics. Jose then stalled offshore New England due to a mid-latitude ridge over Quebec. The cyclone transitioned into an extratropical system by late on September 22, which persisted until dissipating early on September 25.[103]

The government of Antigua and Barbuda began efforts on September 8 to evacuate the entire island of Barbuda prior to Jose's anticipated arrival, as most structures on the island had been heavily damaged or destroyed by Hurricane Irma.[104] Jose likely produced sustained tropical storm force winds in the northern Leeward Islands, though no observations were available because Irma destroyed or damaged wind instruments.[103] In the USVI, heavy rainfall left minor flooding, with damage totaling about $500,000.[105] Jose also caused storm surge and minor wind damage in the United States from North Carolina northward.[106] New Jersey was particularly impacted by storm surge, with the city of North Wildwood alone experiencing about $2 million in damage.[107] A woman died after being caught in a rip current offshore Asbury Park.[108] In Massachusetts, falling power lines left more than 43,000 people without electricity.[109] Damage in the state reached approximately $337,000.[110] When Jose reached peak intensity, it marked the first time on record in the Atlantic basin that two hurricanes, the other being Irma, occurring simultaneously had maximum sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h).[111]

Hurricane Katia

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 5 – September 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 972 mbar (hPa) |

The interaction of a tropical wave and a mid-level trough over the Gulf of Mexico resulted in the development of Tropical Depression Thirteen on September 5, about 40 mi (65 km) east of the Tamaulipas–Veracruz state line. Located in an area of weak steering currents, the cyclone meandered around in the region and strengthened into Tropical Storm Katia at 06:00 UTC on September 6. About 12 hours later, Katia intensified into a hurricane. Late on September 8, the nascent storm peaked as a 105 mph (165 km/h) Category 2 hurricane while it began to move southwestward. However, land interaction began to weaken the hurricane as it approached the Gulf Coast of Mexico. Around 03:00 UTC on September 9, Katia made landfall near Tecolutla in Veracruz at minimal hurricane intensity. The storm quickly dissipated several hours later,[112] although its mid-level circulation remained intact and later spawned what would become Hurricane Otis in the Eastern Pacific.[113]

In preparation for Katia, over 4,000 residents were evacuated from the states of Veracruz and Puebla.[114] Tourists left coastal towns, emergency shelters were opened, and storm drains were cleared before the onset of heavy rainfall.[115] At least 53 municipalities in Mexico were affected by Katia.[116] Heavy rainfall left flooding and numerous mudslides, with 65 mudslides in the city of Xalapa alone. Preliminary reports indicated that 370 homes were flooded. Three deaths were confirmed to have been related to the hurricane, with two from mudslides in Xalapa and one from being swept away by floodwaters Jalcomulco.[116] Approximately 77,000 people were left without power at the height of the storm.[117] Agricultural losses alone reached about $2.85 million,[118] while infrastructural damage totaled about $407,000.[119] Coincidentally, the storm struck Mexico just days after a major earthquake struck the country, worsening the aftermath and recovery.[120]

Hurricane Lee

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 14 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); 962 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on September 13. Contrary to predictions of only gradual organization over the following days, the system rapidly organized, becoming a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on September 14. The NHC upgraded the system to Tropical Storm Lee at 15:00 UTC on the next day, based on an increase in deep convection and an advanced scatterometer (ASCAT) pass which indicated that it was producing minimal tropical-storm-force winds. After encountering wind shear, Lee gradually weakened into a tropical depression on September 17. As Lee moved northwest in tandem with an upper-level trough with periodic bursts of convection, wind shear decreased slightly, allowing Lee to reintensify to a tropical storm again early on September 19 and attaining an initial peak intensity with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) that day. However, wind shear again increased, and Lee opened up into a trough around 12:00 UTC on September 20.[121] The NHC monitored the remnants of Lee intermittently for several days, but regeneration was not considered likely.[122][123] However, the mid-level remnants of the tropical cyclone became intertwined with an upper-level trough; a deep burst of convection led to a new surface circulation, and by 12:00 UTC on September 22, the system reorganized into Tropical Depression Lee. The cyclone then intensified into a tropical storm 12 hours later.[121]

A compact tropical cyclone, Lee organized, as small curved bands wrapped into a small cluster of central convection.[124] A microwave pass around 21:00 UTC on September 23 indicated the formation of a ring of shallow to moderate convection around the center, often a harbinger of rapid intensification.[125] By 06:00 UTC the following day, Lee intensified into a hurricane, based on the presence of an eye on satellite imagery. After attaining winds of 100 mph (155 km/h),[121] the storm weakened slightly due to moderate southeasterly wind shear.[126] By 06:00 UTC on September 26, however, the storm attained Category 2 strength. An eyewall replacement cycle that night led to the emergence of a larger eye surrounded by cold cloud tops, and by 12:00 UTC on September 27, Lee reached its peak intensity as a Category 3 hurricane with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). The system recurved northeast after peak intensity and quickly succumbed to strong northerly wind shear and progressively cooler ocean waters; it weakened below major hurricane strength early on September 28, fell below hurricane strength by 18:00 UTC on September 29, and degenerated to a post-tropical cyclone by 06:00 UTC on September 30, after lacking deep convection for over 12 hours.[121] On October 1, Lee's remnant was absorbed by another extratropical cyclone to the north.[127]

Hurricane Maria

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

.jpg.webp)  | |

| Duration | September 16 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 175 mph (280 km/h) (1-min); 908 mbar (hPa) |

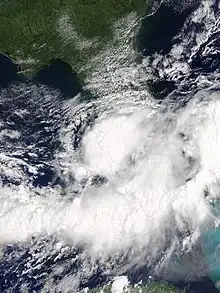

On September 12, a well-defined tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa. The wave initially produced disorganized and scattered deep convection as it moved westward. However, by September 15, convective activity increased and became more organized, including the development of curved cloud bands. Around 12:00 UTC on the following day, a tropical depression formed approximately 665 mi (1,070 km) east of Barbados. Six hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Maria. The cyclone moved west-northwestward and strengthened into a hurricane around 18:00 UTC on September 17. Thereafter, warm sea-surface temperatures and light wind shear allowed Maria to intensify rapidly. By 12:00 UTC on September 18, Maria became a major hurricane upon reaching Category 3 status. Just 12 hours later, the cyclone became a Category 5 hurricane while nearing Dominica. At 01:15 UTC on September 19, Maria struck the island with winds of 165 mph (270 km/h). The storm briefly weakened to Category 4 status by the time it reached the Caribbean, but re-strengthened to a Category 5 hurricane later on September 19. At 03:00 UTC the next day, Maria peaked with sustained winds of 175 mph (280 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 908 mbar (26.8 inHg).[42]

Maria then underwent an eyewall replacement cycle, causing the storm to weaken somewhat. Around 10:15 UTC on September 20, the hurricane made landfall near Yabucoa, Puerto Rico, as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 155 mph (250 km/h). Moving diagonally across the island, Maria weakened significantly due to land interaction, emerging into the Atlantic as a Category 2 late on September 20. Early the next day, the system re-strengthened into a Category 3 hurricane while curving northward around the edge of mid-level high over the western Atlantic. Maria weakened as it continued northward, falling below major hurricane intensity again by early on September 24. Turning sharply eastward on September 28, the cyclone weakened to a tropical storm around that time. Maria then accelerated eastward to east-northeastward across the Atlantic, before becoming extratropical about 535 mi (861 km) southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. The extratropical cyclone dissipated southwest of Ireland on September 30.[42]

Dominica sustained catastrophic damage from Maria, with nearly every structure on the island damaged or destroyed.[128] Surrounding islands were also dealt a devastating blow, with reports of flooding, downed trees, and damaged buildings, with Guadeloupe in particular experiencing extensive damage. The storm almost entirely destroyed the island's banana crop. Puerto Rico also suffered catastrophic damage.[42] The island's electric grid was devastated, leaving all 3.4 million residents without power.[129] By the end of January 2018, only about 65% of electricity on the island had been restored.[42] Many structures were leveled, while floodwaters trapped thousands of citizens. Throughout the island, Maria moderately damaged 294,286 homes, extensively damaged 8,688 homes, and completely destroyed 4,612 homes.[130] The hurricane caused about $90 billion in damage in Puerto Rico and the USVI. Maria damaged or destroyed hundreds of homes in the Dominican Republic, where flooding and landslides isolated many communities. Along the coastline of the mainland United States, tropical storm-force gusts cut power to hundreds of citizens; rip currents offshore led to four deaths and numerous water rescues. A total of 146 people were confirmed to have been directly killed by the hurricane: 64 in Puerto Rico,[42] 65 in Dominica,[131] 5 in the Dominican Republic, 4 in the contiguous United States, 3 in Haiti, 2 in Guadeloupe, and 3 in the USVI.[42] The indirect death toll is much higher; an estimated 2,975 people in total died in Puerto Rico as a result of Hurricane Maria, in the six months after the hurricane, due to the effects of catastrophic damage to the island's infrastructure.[43] Maria was the deadliest hurricane in Dominica since the 1834 Padre Ruíz hurricane,[132] and the deadliest in Puerto Rico since the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane.[133]

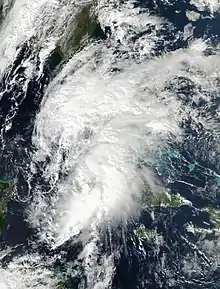

Hurricane Nate

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 4 – October 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 981 mbar (hPa) |

A Central American gyre and a tropical wave interacted, spawning a tropical depression about 40 mi (64 km) south of San Andrés Island on October 4. Steered northwestward by a weak subtropical ridge to the northeast, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Nate around 06:00 UTC on October 5, about six hours before it made landfall in northeastern Nicaragua. Despite land interaction with Central America, Nate weakened minimally before re-emerging into the Caribbean from the north coast of Honduras early the next day. Nate accelerated north-northwestward due to strong deep-layer south-southeasterly flow, with the storm reaching the Gulf of Mexico by early on October 7. Shortly thereafter, the storm intensified into a hurricane. Reaching a forward speed of 29 mph (47 km/h), Nate became the fastest-moving tropical cyclone ever recorded in the Gulf of Mexico. Late on October 7, Nate peaked with sustained winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 981 mbar (29.0 inHg). The cyclone weakened slightly before striking Louisiana near the mouth of the Mississippi River around 00:00 UTC on October 8. Now moving north-northeastward, Nate made a second landfall near Biloxi, Mississippi, at 05:20 UTC. Nate rapidly weakened to a tropical storm just 40 minutes later and then to a tropical depression late on October 8. Early the next day, the system degenerated into a remnant low, which soon became extratropical. Continuing north-northeastward, the extratropical low eventually turned east-northeastward over the Mid-Atlantic and dissipated near Newfoundland on October 11.[134]

Nate and the large gyre combined to produce heavy rainfall over Central America. In Costa Rica, precipitation peaked at 19.19 in (487.4 mm) at Marítima, which is located in Puntarenas Province near the town of Quepos. Several other communities observed rainfall in excess of 10 in (250 mm). The resultant floods were particularly devastating in Costa Rica and Nicaragua, where thousands of homes were damaged or destroyed,[134] with 5,953 homes impacted to some degree in the latter.[135] In the former, dangerous conditions, including floods and landslides, forced at least 5,000 people to flee their homes for emergency shelters.[136] The storm cut off drinking water to nearly 500,000 people, and left 18,500 without power.[135] Flooding also severely damaged agriculture and infrastructure. Overall, the country suffered about ₡322.1 billion (US$562 million) in damage,[134] making it the costliest natural disaster in Costa Rican history.[137] The storm left about $225 million in damage in the United States,[134] with the bulk of the damage occurring in coastal Alabama. Storm surge and abnormally high tides inundated coastal roads and damaged or destroyed hundreds of piers. About 25 homes on the western end of Dauphin Island suffered severe damage from storm surge flooding, while several other homes experienced minor damage.[138] Elsewhere, the storm produced tornadoes, light wind damage, and some localized flooding. Nate caused at least 50 deaths, including 16 in Nicaragua,[134] 14 in Costa Rica,[139] 7 in Panama, 5 in Guatemala, 3 in Honduras,[134] 4 in the United States,[134][138] and 1 in El Salvador, with a further 9 missing accumulative of all affected areas.[134]

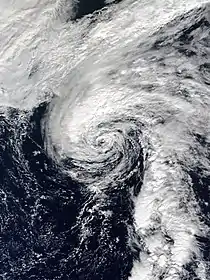

Hurricane Ophelia

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 9 – October 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); 959 mbar (hPa) |

A broad low-pressure area developed along a stationary front well west of the Azores on October 3. Although initially non-tropical in appearance, the low gradually shed its extratropical characteristics while tracking over sea surface temperatures of 81 °F (27 °C), anomalously warm for the region. After a steady increase in convection beginning on October 8, the low transitioned into Tropical Storm Ophelia about 875 mi (1,410 km) west-southwest of the Azores. Ophelia meandered northward, northeastward, and then southeastward over the next few days due to a subtropical ridge to its south and a mid-latitude ridge north of the storm. Late on October 11, the cyclone intensified into a hurricane and began curving northeastward in response to southwesterly flow associated with a broad mid-latitude trough and an approaching cold front. After reaching Category 2 intensity late on October 12, the storm briefly weakened to a Category 1 on the following day, before re-intensifying into a Category 2 hurricane on October 14.[140]

Around 12:00 UTC on October 14, Ophelia strengthened into a Category 3 hurricane and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 959 mbar (28.3 inHg), becoming the easternmost major hurricane in the Atlantic basin on record. Moving northeastward into a region of increasing wind shear and ocean temperatures less than 73 °F (23 °C), Ophelia began rapidly weakening early on October 15, while a strong upper-level trough and jet stream flow caused the storm to begin losing tropical characteristics. Early on October 16, Ophelia ceased to be a tropical cyclone after merging with a strong cold front about 310 mi (500 km) southwest of Mizen Head, Ireland. The extratropical low made landfall on the west coast of Ireland at Category 1-equivalent intensity later that day, several hours before striking northern Scotland. After crossing the North Sea, the low struck southern Norway on October 18 and promptly dissipated.[140]

In the Azores, high winds downed trees, while rainfall left minor flooding on some islands. Although well offshore, winds from Ophelia fanned wildfires in Portugal and Spain. The extratropical remnants of Ophelia produced a wind gust as high as 119 mph (192 km/h) in Ireland,[140] the strongest wind gust ever recorded in the country.[141] As a result, more than 360,000 electrical customers lost power due to falling trees and power lines and poles. A number of homes and buildings suffered damage.[140] With approximately €68.7 million (US$81.1 million) in damage,[142] Ophelia was considered the worst storm in Ireland in 50 years.[140] Five deaths occurred, two from trees falling onto cars and three related to cleanup and repair work in the storm's aftermath.[140][143] In the United Kingdom, wind gusts peaked at 71 mph (114 km/h) in County Down, Northern Ireland. The storm left about 50,000 households without electricity in that portion of the United Kingdom alone.[140]

Tropical Storm Philippe

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 28 – October 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

On October 16, a tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa and entered the Atlantic. The wave tracked westward for several days. By October 24, it began interacting with a Central American gyre while situated over the southwestern Caribbean. By the following day, the interaction resulted in the formation of a low-pressure area. After the low acquired additional convection and the circulation became more well-defined, a tropical depression developed at 12:00 UTC on October 28, about 100 mi (160 km) south-southwest of Isla de la Juventud in Cuba. Moving northeastward due to a large mid-latitude trough over the southeastern United States and western Gulf of Mexico, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Philippe about six hours later. Philippe reached its peak intensity of 40 mph (65 km/h) as recorded on Grand Cayman. Strong wind shear and land interaction with Cuba prevented further intensification. Around 22:00 UTC on October 28, the storm made landfall on the Zapata Peninsula with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). Philippe rapidly weakened and dissipated by 06:00 UTC the next day. Operationally, Philippe was assessed as crossing the Florida Keys and exiting into the western Atlantic, but post-analysis showed that it was a non-tropical area of low pressure that was interacting with Philippe.[144]

The storm produced heavy rainfall in the Cayman Islands, Cuba, Florida, and the Bahamas. In Florida, rainfall generally ranged from 2 to 4 in (50.8 to 102 mm), though isolated precipitation totals of 10 to 11 in (250 to 280 mm) were reported in eastern Broward and Palm Beach counties. Philippe spawned three EF0 tornadoes in southeastern Florida. One of those damaged dozens of homes in Boynton Beach, while another produced a wind gust of 74 mph (119 km/h) in West Palm Beach.[144]

Tropical Storm Rina

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 5 – November 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 991 mbar (hPa) |

On October 26, a low-latitude tropical wave left the coast of Africa accompanied by a limited amount of deep convection. It continued to produce disorganized showers and thunderstorms while moving westward through the Intertropical Convergence Zone. Then, on October 31, the wave fractured as the result of interaction with a large mid- to upper-level trough that had become well established over the central Atlantic Ocean. The southerly flow on the east side of the trough transferred a significant amount of tropical moisture northward, and a weak and elongated low pressure system formed in association with the fractured portion of the tropical wave a few days later. On November 4, the low developed a well-defined center, and 18:00 UTC on November 5, it’s deep convection had become sufficiently organized for the system to be classified as a tropical depression, when it was located about 805 mi (1,295 km) east-southeast of Bermuda. Though beset with wind shear from the west, the system continued to strengthen, and at 00:00 UTC on November 7, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Rina. As it started on a northerly track, Rina continued to strengthen despite strong shear and dry air intrusion, and also began to show subtropical characteristics marked by most of the deep convection and strongest winds well removed from the center. Nonetheless, Rina strengthened into a strong tropical storm with peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h), while located about 750 mi (1,200 km) south-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. Shortly after attaining peak strength, convection began to wane and became displaced well from the center of the system, while the overall structure became comma-like in appearance on satellite imagery, signifying that Rina was transitioning into a post-tropical cyclone. During this time the storm accelerated northward between a ridge to its east and a trough to its west, and merged with a complex extratropical system around 18:00 UTC on November 9.[145] This system, as Cyclone Numa, subsequently acquired subtropical characteristics, becoming a rare "medicane".[146]

Other system

The NHC began monitoring a tropical wave that just emerged off the coast of Africa on August 13, which was expected to merge with an area of low pressure southwest of Cape Verde within a few days. Instead the two systems remained separate, with the first eventually becoming Potential Tropical Cyclone Ten on August 27, to the northeast of Florida, and the other low-pressure eventually becoming Hurricane Harvey.[36] The NHC gave this disturbance a 90% chance of becoming a tropical cyclone within the next 48 hours.[147] In preparation for a potential tropical cyclone, tropical storm watches and warnings were issued in South Carolina and North Carolina beginning on August 27. A reconnaissance flight indicated that the system had tropical storm-force winds, though it lacked a well-defined circulation.[148] After attaining 1-minute sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h), the system subsequently began to undergo an extratropical transition.[149] Consequently, the NHC issued its last advisory on the system at 21:00 UTC on August 29, declaring the system to be an extratropical low.[150] However, after the storm became extratropical, it strengthened, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h),[151] before being absorbed by a larger extratropical system, Windstorm Perryman, on September 4.[152][153]

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Atlantic in 2017.[154] This was the same list used in the 2011 season, with the exception of the name Irma, which replaced Irene. Even so, no names were used for the first time this year, as Irma had been on a previous naming list, and was used during the 1978 season. The names not retired from this list are being used in the 2023 season.

The usage of the name "Don" in July garnered some attention relating to United States President Donald Trump. Max Mayfield, former director of the NHC, clarified that the name had no relation to Trump and was chosen in 2006 as a replacement for Dennis. Regardless, some outlets such as the Associated Press "poked fun" at the name and Trump.[155][156]

Retirement

On April 11, 2018, at the 40th session of the RA IV hurricane committee, the World Meteorological Organization retired the names Harvey, Irma, Maria, and Nate from its rotating naming lists due to the number of deaths and amount of damage they caused, and they will not be used again for another Atlantic hurricane. They were replaced with Harold, Idalia, Margot, and Nigel for the 2023 season, respectively. With four names retired, the 2017 season is tied with the 1955, 1995, and 2004 seasons for the second-highest number of storm names retired after an Atlantic season, surpassed only by the 2005 season, which had five retired names.[157]

Season effects

This is a table of all the tropical cyclones that formed in the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, intensities, affected areas, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a tropical wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in 2017 USD. Potential tropical cyclones are not included in this table.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arlene | April 19–21 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 990 | None | None | None | |||

| Bret | June 19–20 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1007 | Guyana, Venezuela, Trinidad and Tobago, Windward Islands | ≥ $2.96 million | 1 (1) | [158][50][52] | ||

| Cindy | June 20–23 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 991 | Central America, Greater Antilles, Yucatán Peninsula, Southern United States, Eastern United States | $25 million | 1 (2) | [54][56][57] | ||

| Four | July 5–7 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1009 | None | None | None | |||

| Don | July 17–18 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1005 | Windward Islands, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago | None | None | |||

| Emily | July 30 – August 1 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1001 | Florida | $10 million | None | [67] | ||

| Franklin | August 7–10 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 981 | Central America, Greater Antilles, Yucatán Peninsula, Central Mexico | $15 million | None | [77] | ||

| Gert | August 12–17 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 962 | Bermuda, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada | None | 0 (2) | [79][80] | ||

| Harvey | August 17 – September 1 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | 937 | South America, Windward Islands, Greater Antilles, Central America, Yucatán Peninsula, Northeastern Mexico, Southern United States, Eastern United States | $125 billion | 68 (39) | [36][89] | ||

| Irma | August 30 – September 12 | Category 5 hurricane | 180 (285) | 914 | Cape Verde, Leeward Islands, Greater Antilles, Lucayan Archipelago, Southeastern United States, Northeastern United States | $77.16 billion | 52 (82) | [92][94][97][98][38] | ||

| Jose | September 5–22 | Category 4 hurricane | 155 (250) | 938 | Leeward Islands, East Coast of the United States | $2.84 million | 0 (1) | [105][107][110] | ||

| Katia | September 5–9 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 972 | Eastern Mexico | $3.26 million | 3 (0) | [118][119][116] | ||

| Lee | September 15–30 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | 962 | None | None | None | |||

| Maria | September 16–30 | Category 5 hurricane | 175 (280) | 908 | Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles, Lucayan Archipelago, Southeastern United States, Mid-Atlantic States, Western Europe | $91.61 billion | 3,059 | [42][131][43] | ||

| Nate | October 4–8 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 981 | Central America, Yucatan Peninsula, Greater Antilles, Southeastern United States, Northeastern United States, Atlantic Canada | $787 million | 46 (2) | [134][139][138] | ||

| Ophelia | October 9–15 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | 959 | Azores, Portugal, Spain, France, Ireland, United Kingdom, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Russia | > $87.7 million | 2 (3) | [140][142][143] | ||

| Philippe | October 28–29 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1000 | Central America, Greater Antilles, Yucatán Peninsula, East Coast of the United States | $100 million | 5 | |||

| Rina | November 5–9 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 991 | None | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 18 systems | April 19 – November 9 | 180 (285) | 908 | ≥ $294.803 billion | 3,237 (132) | |||||

See also

- Weather of 2017

- Tropical cyclones in 2017

- 2017 Pacific hurricane season

- 2017 Pacific typhoon season

- 2017 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2016–17, 2017–18

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2016–17, 2017–18

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2016–17, 2017–18

- Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone

- South Atlantic tropical cyclone

- Tropical cyclones and climate change

Footnotes

- All damage figures are in 2017 USD, unless otherwise noted

- A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[1]

- There is an undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910, due to the lack of modern observation techniques, see Tropical cyclone observation. This may have led to significantly lower ACE ratings for hurricane seasons prior to 1910.[23][24]

References

- Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 23, 2013. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- "Update on National Hurricane Center Products and Services for 2017" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. May 23, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Paul J. Brennan (June 18, 2017). Potential Tropical Cyclone Two Advisory Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 19, 2011. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- "North Atlantic Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (December 13, 2016). Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2017 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (April 5, 2017). April Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2017 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Phillip J. Klotzbach; Michael M. Bell (April 6, 2017). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2017" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- Jon Erdman (April 26, 2017). "2017 Atlantic Hurricane Season Forecast Calls For a Near-Average Number of Storms, Less Active Than 2016". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- "NCSU researchers predict 'normal' hurricane season". WRAL. April 18, 2017. Archived from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Jon Erdman (June 1, 2017). "2017 Atlantic Hurricane Season Forecast Update Calls For An Above-Average Number Of Storms". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on May 19, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- "Above-normal Atlantic hurricane season is most likely this year". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 25, 2017. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (May 26, 2017). Pre-Season Forecast for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2017 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 25, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Phillip J. Klotzbach; Michael M. Bell (June 1, 2017). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2017" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- "North Atlantic tropical storm seasonal forecast 2017". Met Office. June 1, 2017. Archived from the original on June 21, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (July 4, 2017). July Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2017 (PDF) (Report). Tropical Storm Risk. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Phillip J. Klotzbach; Michael M. Bell (July 5, 2017). "Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Phillip J. Klotzbach; Michael M. Bell (August 4, 2017). "Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (August 4, 2017). August Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2017 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- "Early-season storms one indicator of active Atlantic hurricane season ahead". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2017. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Christopher W. Landsea (2019). "Subject: E11) How many tropical cyclones have there been each year in the Atlantic basin? What years were the greatest and fewest seen?". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on April 22, 2006. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- Phillip J. Klotzbach (December 14, 2016). "Qualitative Discussion of Atlantic Basin Seasonal Hurricane Activity for 2017" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 25, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- Landsea, Christopher W. (2010-05-08). "Subject: E11) How many tropical cyclones have there been each year in the Atlantic basin? What years were the greatest and fewest seen?". U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- Christoper W. Landsea, Hurricane Research Division (2014-03-26). "HURDAT Re-analysis Original vs. Revised HURDAT". NOAA. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- "Tropical Cyclone Climatology". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- Phillip J. Klotzbach; Michael M. Bell (November 30, 2017). Summary of 2017 Atlantic Tropical Cyclone Activity and Verification of Authors' Seasonal and Two-Week Forecasts (PDF) (Report). Colorado State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- "2017 Atlantic Hurricane Season Was the Busiest Since 2005". New York, New York: Insurance Information Institute. November 30, 2017. Archived from the original on September 30, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Jeff Masters (November 30, 2017). "Good Riddance to the Brutal Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2017". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- Michael J. Brennan (March 5, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Bret (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2019.