Trotskyism in Vietnam

Trotskyism in Vietnam (Vietnamese: Trăng-câu Đệ-tứ Đảng) was represented by those who, in left opposition to the Indochinese Communist Party (PCI) of Nguyen Ai Quoc (Ho Chi Minh), identified with the call by Leon Trotsky to re-found "vanguard parties of proletariat" on principles of "proletarian internationalism" and of "permanent revolution". Active in the 1930s in organising the Saigon waterfront, industry and transport, Trotskyists presented a significant challenge to the Moscow-aligned party in Cochinchina. Following the September 1945 Saigon uprising against the restoration of French colonial rule, Vietnamese Trotskyists were systematically hunted down and eliminated by both the French Sûreté and the Communist-front Viet Minh.

| Part of a series on |

| Trotskyism |

|---|

|

The Emergence of Left Opposition

An identifiable Trotskyist tendency among Vietnamese revolutionary circles emerges first in Paris among the student youth of the Annamite Independence Party.[2] Following the bloody suppression of the Yên Bái mutiny, their leader Tạ Thu Thâu expressed their view of the revolution in Indochina in the pages of the Left Opposition La Verité (May and June issues, 1930). The revolution would not follow the path the Third International had endorsed in making common cause with the Kuomintang in China. A commitment to a broad nationalist front ("Sun Yat-sen ism") would betray the revolutionary interests of the anti-colonial struggle. For the colonised the choice was no longer between independence and slavery, but between socialism and nationalism. As "the social enemy of imperialism." the worker and peasant masses would free themselves from oppression under the French overseer only through their own organised action. "Independence is inseparable from proletarian revolution."[3]

For organising protests against the execution of Yên Bái insurgent leaders, in May 1930 Tạ Thu Thâu and eighteen of his compatriots were arrested and deported back to Cochinchina.

In Saigon the deportees found several groups of militants open to the theses of Left Opposition, some within the PCI. In November 1931 dissidents emerging from within the Party formed the October Left Opposition (Tả Đối Lập Tháng Mười) around the clandestine journal Tháng Mười (October). These included Hồ Hữu Tường, Dao Hung Long (alias Anh Gia), and Phan Văn Hùm. Declaring that, "being at all times a reactionary ideology, nationalism cannot succeed but to forge a new chain for the working class",[4] in Paris in July 1930 they had formed an Indochinese Group within the Communist League [Lien Minh Cong San Doan/Groupe indochinois de la Ligue Communiste (Opposition)],[5] the French section of the International Left Opposition.

Once considered "the theoretician of the Vietnamese contingent in Moscow,"[6] Tường was calling for a new "mass-based" party arising directly "out of the real struggle of the proletariat of the cities and countryside."[7] But the repression triggered by strikes by in Saigon-Cholon and by a peasant jacquerie in the surrounding districts that for all factions organisational activity proved near impossible. Between 1930 and the end of 1932, more than 12,000 political prisoners were taken in Cochinchina, of whom 7,000 were sent to the penal colonies. The structures of the Party and of the Left Opposition alike were shattered.[8]

The Struggle and the Internationalist League

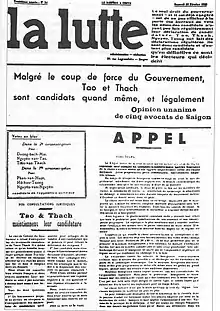

In 1933, several factional representatives, including Tạ Thu Thâu, Nguyễn Văn Tạo of the PCI [later to be labour minister in Hanoi][9] and the anarchist Trinh Hung Ngau, regrouped around charismatic figure of Nguyễn An Ninh, and took the initiative of legally opposing the colonial regime in the Saigon municipal elections of April–May 1933. They put forward a common "Workers' List" and briefly published a newspaper (in French to get around the political restrictions on Vietnamese), La Lutte (The Struggle) to rally support for it. In spite of the restricted franchise, two of this Struggle group were elected (although denied their seats), the independent (later Trotskyist) Tran Van Thach and Nguyễn Văn Tạo.

In 1934 the La Lutte the collaboration was revived on the basis of a formal Party-Oppositionist entente: "struggle oriented against the colonial power and its constitutionalist allies, support of the demands of workers and peasants without regard to which of the two groups they were affiliated with, diffusion of classic Marxist thought, [and] rejection of all attacks against the USSR and against either current."[10] In the March 1935 Cochinchina Colonial Council election candidates supported by La Lutte obtained 17% of the votes, although none were elected. Two months later in the Saigon municipal elections four of six candidates on a joint "Workers' Slate," including Tạ Thu Thâu and Nguyễn Văn Tạo, were elected, although only Tran Van Thach as the ostensible non-communist was allowed his seat.[11]

At the end of 1935, unwilling to enter into a further accommodation with the "Stalinists, " the October Group of Hồ Hữu Tường, Lu Sanh Hanh and of Ngô Văn (the chronicler of the Trotskyist struggle in later exile) formed the core of the League of Internationalist Communists for the Construction of the Fourth International (Chanh Doan Cong San Quoc Te Chu Nghia--Phai Tan Thanh De Tu Quoc). The League maintained a "complete system of clandestine and legal publications"[12] including its own weekly “organ of proletarian defence and Marxist combat,” Le Militant (this carried Lenin's Testament with its warnings against Stalin, and Trotsky's polemics against the Popular Front),[13] topical pamphlets in both French and Vietnamese (including Ngô Văn's denunciation of the Moscow Trials) and an agitational bulletin, Thay Tho (Wage and Salary Workers).[14] After Le Militant was suppressed, from January 1939 the League/the Octobrists began clandestinely publishing Tia Sang (The Spark).

The title, The Spark, may have been a reference to Tia Sang (the Spark) group in Hanoi, and suggests an organisational connection. In 1937-38, this northern group had put out a weekly, Thoi Dam (Chronicles), with a call to workers and peasants to set up "unified people's committees in the struggle for rice, freedom and democracy."[15] Octobrists are reported to have been active in labour organising in Hanoi, Haiphong and Vinh.[16]

While the Stalinists urged respect for the law to the peasants who had begun to agitate in a violent manner against direct and indirect taxes and for a reduction in rents, the League's call for "action committees" was met with widespread arrests. The "first trial of the Fourth International", the trial League activists, opened in Saigon on 31 August 1936. Following publicised testimony of their torture and maltreatment, Lu Sanh Hanh and seven of his comrades received moderated sentences of 6 to 18 months.[17]

In Saigon, with a renewed upsurge culminating in the summer of 1937 in general dock and transport strikes, the tide on the left seemed to be running in favour of the Trotskyists. Judging by the frequency of the warnings in the clandestine Communist press against Trotskyism the influence of the oppositionists in the organised unrest was "considerable" if not "preponderant."[18]

Tạ Thu Thâu and Nguyễn Văn Tạo came together for the last time in the April 1937 city council elections, both being elected. Together with the lengthening shadow of the Moscow Trials (obliging the Party loyalists to denounce their erstwhile colleagues as "the twin brothers of fascism"), growing disagreement over the new PCF-supported Popular Front government in France ensured a split.[19]

The La Lutte group had entered its own Popular Front known under the name of the Indo Chinese Congress Movement (Phong-tiao-Dong-duong-Dai-hoi) with the bourgeois Constitutionalist Party, in order to draw up demands relating to the political, economic and social reforms that were to be presented to the new government in Paris.[20] But the leftward shift in the French national Assembly in Thâu's view had not brought meaningful change. He and his comrades continued to be arrested during labour strikes, and preparations for a popular congress in response to the government's promise of colonial consultation had been suppressed. Colonial Minister Marius Moutet, a Socialist commented that he had sought "a wide consultation with all elements of the popular [will]," but with "Trotskyist-Communists intervening in the villages to menace and intimidate the peasant part of the population, taking all authority from the public officials," the necessary "formula" had not been found.[21]

Thâu's motion attacking the Popular Front for betraying the promises of reforms in the colonies was rejected by the PCI faction and in June 1937 the Stalinists withdrew from La Lutte.[22]

Labour unrest culminated in the general strike of 1937 that included workers in the arsenal at Saigon, of the Trans-Indo Chinese Railway (Saigon-Hanoi), the Tonkin miners and the coolies of the rubber plantations. Their demands were for an eight hour day, trade union rights, rights of assembly, a free press, etc. The government resorted to repression and in October the Indochinese Congress Movement was itself dissolved. Trotskyist and Stalinist papers that had sometimes been able to appear in the Vietnamese language were banned once more, and the labour legislation remained a dead letter.[20]

The Workers vs. the Democratic Platform

In April 1939, together with the Octobrists, the now wholly Trotskyist La Lutte group celebrated what a reviewer of Ngô Văn's later account[23] describes as "the only instance prior to 1945 in which the politics of 'permanent revolution' oriented to worker and peasant opposition to colonialism won out, however ephemerally, against Stalinist 'stage theory' in a public arena."[24] In elections to the colonial Cochinchina Council a "United Workers and Peasants" slate, led by Tạ Thu Thâu, triumphed over both the Communist Party's Democratic Front and the "bourgeois" Constitutionalists with fully 80 per cent of the vote.

Revolutionary theory had not been the issue for the restricted property-and-business-tax-payer electorate. Rather it had been the colonial defence levy that the PCI, in the spirit of Franco-Soviet accord, had felt obliged to support.[25] Nonetheless the contest illustrated the ideological gulf between the Party and the left opposition. The Workers and Peasants platform had been revolutionary (calls for workers control and radical land re-distribution) and reflected the analysis Tạ Thu Thâu had outlined in La Verité. The "real, organic liaison between the indigenous bourgeoisie and French imperialism" was such that the organisation of "the proletarian and peasant masses" was the only force capable of liberating the country. The question of independence was "bound up with that of the proletarian socialist revolution."[26]

The Democratic platform, with its calls for national unity and relatively modest demands for constitutional change, was presented by a party whose leading cadres "emphasised much more the exterior development of capitalism", "used the word 'imperialism' much more often in their discussions," talked about “nonequivalent exchange,” and of "the continuing feudal nature of Vietnamese society."[27] It was a party for whom the immediate object of anti-colonial struggle was national, not socialist.

At the same time, the Democratic platform had represented a party with a much greater national organisation and presence. The Trotskyists were concentrated in industrial and commercial centres, and in French direct-rule Cochinchina, where it was possible to have a keener sense of proximities to France. (Ho Huu Thuong's vision was of a revolutionary general strike coordinated with the French proletariat).[14]

The greater resilience of the PCI—their ability to regroup and rebuild in the face of repression—was due to its organisation in the countryside and across Annam (central Vietnam) and Tonkin in the North. In these "protectorates" the French, under the titular authority of the Bảo Đại had retained traditional elements of rural administration. Their rule had the calculated appearance of being external to a still extant indigenous culture, and allowed greater play to the idea of a national society that might be mobilised against the foreign overseer.[28][25]

Such as it was, the political opening against the Communist Party closed with the Hitler-Stalin Pact of August 23, 1939. Moscow ordered a return to direct confrontation with the French. In Cochinchina the Party obliged with a disastrous peasant revolt.

Belatedly, the Luttuers, then numbering then perhaps 3000,[29] and the smaller number of Octobrists united as the official section of the newly constituted Fourth International. They formed the International Communist League (Vietnam) (ICL), or less formally as The Fourth Internationalist Party (Trăng Câu Đệ Tứ Đảng).[30] But the French law of September 26, 1939, which legally dissolved the French Communist Party, was applied in Indochina to Stalinists and Trotskyists aiike. The Indochinese Communist Party and the Fourth Internationalists were driven underground for the duration of the war.

The North and the Hòn Gai-Cẩm Phả "Commune"

Opportunity for open political struggle returned with the formal surrender of the occupying Japanese in August 1945. But events then moved rapidly to demonstrate the Trotskyists' relative isolation. There was little intimacy with developments to the north where, in Hanoi on September 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh and his a new Front for the Independence of Vietnam, the Viet Minh, proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

The lack of connection was made "painfully clear" when Ngô Văn and his comrades found they had "no way of finding out what was happening" following reports that in the Hòn Gai-Cẩm Phả coal region north of Haiphong, under the indifferent gaze of the defeated Japanese 30,000 workers had elected councils to run mines, public services and transport, and were applying the principle of equal wages for all types of work, whether manual or intellectual.[31][32] Later they were to learn that, after three months of revolutionary autonomy, the commune had been forcibly integrated into "the military-police structure" of the new republic.[33]

Released from detention in 1944, in April 1945 Tạ Thu Thau and a small band had travelled to the (famine-stricken) North. They were introduced to clandestine meetings of mine workers and peasants by a "fraternal group" publishing the bulletin in Hanoi Chiến Đấu (Combat). This was the rump of the ICL in the north, many of their comrades having chosen to join the Viet Minh. Now styling themselves the Socialist Workers Party of Northern Vietnam (Dang Tho Thuyen Xa Hoi Viet Bac), their call, as in the South, was for workers' control, land redistribution and for armed resistance to a return of the French. Whether they, or other Trotskyist groups, played any role in the Hongai-Camphai events is unclear. On Ho Chi Minh's orders they were already being rounded up and executed.[34][35]

Hunted and pursued south by the Viet Minh, Tạ Thu Thâu was captured in early September at Quang Ngai. A year later in Paris, the French socialist Daniel Guérin recalls that when he asked Ho Chi Minh about Tạ Thu Thâu's fate, Ho replied, "with unfeigned emotion,“ that "'Thâu was a great patriot and we mourn him." But he then added, "in a steady voice, 'all those who do not follow the line which I have laid down will be broken.'”[36]

The September 1945 Saigon Uprising

.jpg.webp)

On August 24 the Viet Minh declared a provisional administration, a Southern Administrative Committee, in Saigon. When, for the declared purpose of disarming the Japanese, the Viet-Minh accommodated the landing and strategic positioning of British and British-Indian troops, rival political groups turned out in force. On September 7 and 8, 1945, in the delta city of Cần Thơ the Committee had to rely on what had been the Japanese-auxiliary, Jeunesse d'Avant-Garde/Thanh Nien Tienphong [Vanguard Youth]. They fired upon crowds, joined by the ICL, demanding arms against a French colonial restoration.[37]

In Saigon, the brutal reassertion of French authority under the protection of British, British-Indian and British-commandeered Japanese, forces triggered a general uprising on September 23.[38] Under the slogan "Land to the Peasants! Factories to the workers!," the ICL called on the population to arm themselves and organise in councils. To co-ordinate these efforts the Internationalists established a Popular Revolutionary Committee, an "embryonic soviet that placed its stamp upon the region of Saigon-Cholon, Gia-dinh and Bien-Hoa."[39] Delegates issued "a declaration in which they affirmed their independence from the political parties and resolutely condemned any attempt to restrict the autonomy of the decisions taken by workers and peasants."[40]

With other League comrades, Ngô Văn joined in arms with streetcar workers. In the "internationalist spirit of the League," the workers had broken with their union, General Confederation of Labour (renamed by the Viet Minh "Workers for National Salvation"). Refusing the yellow star of the Viet-Minh, they mustered under the unadorned red flag "of their own class emancipation."[41] They placed themselves under the overall command of Tran Dinh Minh, a young Trotskyist from the north.[20] But the militias were hit hard by the returning French. Ngô Văn records two hundred alone being massacred, October 3, at the Thi Nghe bridge.[42]

As they fell back into the countryside, they and other independent formations (armed groups of independent nationalists and the syncretic Hoa Hao and Cao Dai sects) were caught in the crossfire as the Viet-Minh returned to surround the city.[43][44] Dương Bạch Mai, who had been among the Stalinists on the original editorial board of La Lutte,[45] led Vietminh security in hunting down his former colleagues on the paper. By the end of October they had captured and executed, among others, Nguyen Van Tien, the former managing editor, and Phan Văn Hùm.[46]

Vietnamese Trotskyism in Exile

Forsaking his revolutionary principles, Hồ Hữu Tường took refuge with the French Bảo Đại puppet government (later he became a deputy in the "farcical 'opposition'" under the military regime of Nguyen Van Thieu).[14] But "harassed by the Sûreté in the city and denied refuge in a countryside dominated by the two terrors, the French and the Viet-Minh,"[47] most ICL survivors appear to be those who, like Ngô Văn, sought exile in France.

In 1946, as many as 500 exiles were reported to be members of the Groupe Communiste Internationaliste de Vietnam (GCI — Internationalist Communist Group of Vietnam). They published a paper titled, in the tradition of La Lutte, Tranh Dau (Struggle).[48]

In what, presumably, was a still smaller exile publication, Thieng Tho (Workers' Voice), Ngô Văn wrote an opinion piece under the name Dong Vu (October 30, 1951) "Prolétaires et paysans, retournez vos fusils!" [Workers and Peasants, Turn Your Guns in the Other Direction!]. If Ho Chi Minh won out over the French-puppet Bảo Đại government, workers and peasants would simply have changed masters. Those with guns in their hands should fight for their own emancipation, following the example of the Russian workers, peasants and soldiers who formed soviets in 1917, or the German worker's and soldiers' councils of 1918-1919.[49] But this clearly, was a minority position.

In line with continued defence of the Soviet Union by Trotskyists internationally as a "(degenerated) workers' state," Vietnamese Trotskyists muted their criticism of the Viet Minh regime. The slogan, adopted as Ngô Văn noted "despite the assassination of almost all their comrades in Vietnam by Ho Chi Minh's hired thugs," was "Defend the government of Ho Chi Minh against the attacks of imperialism."[50]

As the Indochinese war intensified in the late 1940s, the French government began massive deportations of Vietnamese, including about three-quarters of the Trotskyists. The latter "simply disappeared after their return to Vietnam, presumably through capitulation to the Viet Minh Stalinists or liquidation by either the Stalinists or the French." By 1951-52 there were only about 70 Vietnamese ostensible Trotskyists left in France. La Lutte and League supporters combined in the Bolshevik-Leninist Group of Vietnam (BLGV). This continued to exist, at least in some form, until as late as 1974.[51]

By the early 1980s the history of the Vietnamese Trotskyist movement, which in the 1930s may been the most important expression of left opposition in Asia (possibly greater in its scope than in China and in advance of its emergence in India),[45] had been "all but forgotten by the Trotskyists themselves." Robert Alexander suggests two reasons for this.[2]

First, there was "the very thoroughness of the Stalinist extermination of the Trotskyist leadership in Vietnam." This "left no outstanding figure of the movement alive to tell about it outside the country, and to continue to be active in one or another faction of the international Trotskyist movement."[2] Ngô Văn is probably the most commonly cited witness to the story. But Văn's memoirs are prefaced with a repudiation of "Bolshevism-Leninism-Trotskyism." In France, experiences shared with refugees from Spanish Civil War, anarchists and veterans of the POUM (The Workers' Party of Marxist Unification), "permanently distanced" Văn from the politics of "so-called 'workers' parties."[52]

The second reason, however, is precisely that which Ngô Văn underscored in his Thieng Tho article (and in his later memorials for fallen friends and comrades). It is what Robert Alexander recounts as "the passion, effort and attention paid by Trotskyists of virtually all countries and all factions to support of the Stalinist side during the long and cruel Vietnam War, which in one form or another went on for thirty years, from 1945 to 1975. With such strong commitment to the 'degenerated workers state' of Ho Chi Minh and his successors, any memories of what he had done to fellow Trotskyists had to be at least a source of discomfort if not outright embarrassment to the world Trotskyist movement."[2]

See also

References

- Book review: Revolutionaries They Could Not Break, by Ngo Van

- Alexander, Robert J. (2001), Vietnamese Trotskyism (https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/alex/works/in_trot/viet.htm). Retrieved 10 October 2019

- Văn, Ngô (2010) In the Crossfire: Adventures of a Vietnamese Revolutionary. AK Press, Oakland CA,’, pp. 159-160

- Van, Ngo (1989). "Le mouvement IVe Internationale en lndochine 1930-1939" (PDF). Cahiers Leon Trotsky (40): 30. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Văn (2010), pp. 52, 156,169-170

- Tai, Hue-Tam Ho (1996), Radicalism and the Origins of the Vietnamese Revolution, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA., p. 242

- Văn (2010), p. 168

- Văn (2010), pp. 54-55

- Patti, Archimedes L. A., (1982) .Why Viet Nam?: Prelude to America's Albatross, University of California Press, p. 494

- Hemery, Daniel (1975), Revolutionnaires Vietnamiens et pouvoir colonial en Indochine. Paris: François Maspero, p. 63. ISBN 978-2707107688

- Taylor, K. W., (2013) A History of the Vietnamese, Cambridge University Press, p. 515

- Hémery (1975), p.398

- Van (2010), p. 86

- Van (2010), pp. 168-169.

- Van (2010), p. 173

- Patti (1982), p. 522

- "Ngo Van Xuyet: On Vietnam". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- Hemery (1975), Appendix 24.

- Frank N. Trager (ed.). Marxism in Southeast Asia; A Study of Four Countries. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1959. p. 142

- Xuyet, Ngo Van (1968). "On Vietnam: 1. The La Lutte Group and the Workers' and Peasants' Movement (1933-37)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- Hemery (1975), p. 388

- Văn (2010), p. 161

- Van, Ngo (2000), Viet-nam 1920-1945: Révolution et contre-révolution sous la domination coloniale, Paris: Nautilus Editions

- Goldner, Loren (1997) "The Anti-Colonial Movement in Vietnam". New Politics, Vol VI, No. 3, pp. 135–141.

- McDowell, Manfred (2011). "Sky Without Light: A Vietnamese Tragedy". New Politics. XIII (3): 131–138. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Ngo Van Xuyet, Ta Thu Thau: Vietnamese Trotskyist Leader, https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/revhist/backiss/vol3/no2/thau.html

- Hémery (1975), pp. 46-47

- Duiker, William J. (1981), The Communist Road to Power in Vietnam, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

- AWL, The forgotten massacre of the Vietnamese Trotskyists.https://www.workersliberty.org/story/2005/09/12/forgotten-massacre-vietnamese-trotskyists

- Patti, Archimedes L.A. (1981). Why Vietnam?: Prelude to America's Albatross. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 522–523. ISBN 9780520041561.

- Van (2010), pp.120-121

- McDowell (2011), p. 133

- Ngo Van Xuyet [Ngo Van], A Hundred Year War, https://libcom.org/history/hundred-year-war-ngo-van-xuyet

- Văn (2010), p. 162, pp. 178-179

- Marr, David G. (2013). Vietnam: State, War, and Revolution (1945–1946). University of California Press. pp. 409–410. ISBN 9780520274150.

- Guérin, Daniel. (1954) Aux services des colonises, 1930–1953, Paris: Editions Minuit, p. 22

- Marr, David G. (15 April 2013). Vietnam: State, War, and Revolution (1945–1946). University of California Press. pp. 408–409. ISBN 9780520274150.

- Rosie, George; Borum, Bradley (1986). Operation Masterdom: Britain's Secret War in Vietnam. Mainstream. ISBN 9781851580002.

- Ngô Văn, A ‘Moscow Trial’ in Ho Chi Minh's Guerilla Movement. https://libcom.org/library/%E2%80%98moscow-trial%E2%80%99-ho-chi-minh%E2%80%99s-guerilla-movement

- Văn (2010), p. 125

- Ngô Văn, 1945: The Saigon Commune, https://libcom.org/files/1945%20The%20Saigon%20commune.pdf

- Ngô Văn (2010), p. 131

- Van (2010), pp. 128-129.

- "Phong Trào Truy Lùng Và Xử Án Việt Gian". Phật Giáo Hòa Hảo. 2005.

- Alexander, Robert J. (1991), International Trotskyism, 1929-1985: A Documented Analysis of the Movement. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 961-962

- Van (2010), p. 157

- Văn (2010), p. 149

- Sharpe, John (1976), Stalinism and Trotskyism in Vietnam, New York: Spartacist Publishing Co., p. 49

- Văn (2010), p. 200

- Văn (2010), p. 199

- Sharpe (1976), pp. 50-54

- Văn (2010), p. 2

External links

- Robert J. Alexander, "Vietnamese Trotskyism." https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/alex/works/in_trot/viet.htm

- Manfred McDowell, "Sky without Light: a Vietnamese Tragedy." https://newpol.org/review/sky-without-light-vietnamese-tragedy/

Reading

- Robert J. Alexander, International Trotskyism 1929–1985: A documented analysis of the movement. Duke University Press, Durham NC, 1991.

- William J. Duiker: The Communist Road to Power in Vietnam, Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado, 1981.

- Daniel Hémery, Révolutionaires vietnamiens et pouvoir colonial en Indochine, François Maspero, Paris, 1975.

- Hue-Tam Ho Tai, Radicalism and the Origins of the Vietnamese Revolution, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA. 1996.

- Anh Van and Jacqueline Roussel, National Movements and Class Struggle in Vietnam, New Park Publications, London 1987.

- Ngo Van , Viet-nam 1920-1945: Révolution et contre-révolution sous la domination coloniale, Paris: Nautilus Editions, 2000. Excerpts appear in English as Revolutionaries They Could Not Break: The Fight for the Fourth International in Vietnam. London: Index Pr. 1995.

- Ngô Văn,In the Crossfire: Adventures of a Vietnamese Revolutionary. AK Press, Oakland CA, 2010.