Twill

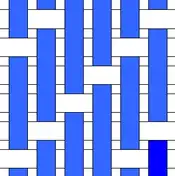

Twill is a type of textile weave with a pattern of diagonal parallel ribs. It is one of three fundamental types of textile weaves along with plain weave and satin. It is made by passing the weft thread over one or more warp threads then under two or more warp threads and so on, with a "step," or offset, between rows to create the characteristic diagonal pattern.[1] Because of this structure, twill generally drapes well.

Classification

Twill weaves can be classified from four points of view:

- According to the stepping:

- Warp-way: 3/1 warp way twill, etc.

- Weft-way: 2/3 weft way twill, etc.

- According to the direction of twill lines on the face of the fabric:

- S-twill, or left-hand twill weave: 2/1 S, etc.

- Z-twill, or right-hand twill weave: 3/2 Z, etc.

- According to the face yarn (warp or weft):

- Warp face twill weave: 4/2 S, etc.

- Weft face twill weave: 1/3 Z, etc.

- Double face twill weave: 3/3 Z, etc.

- According to the nature of the produced twill line:

- Simple twill weave: 1/2 S, 3/1 Z etc.

- Expanded twill weave: 4/3 S, 3/2 Z, etc.

- Multiple twill weave: 2/3/3/1 S, etc.

Structure

In a twill weave, each weft or filling yarn floats across the warp yarns in a progression of interlacings to the right or left, forming a pattern of distinct diagonal lines. This diagonal pattern is also known as a wale. A float is the portion of a yarn that crosses over two or more perpendicular yarns.

A twill weave requires three or more harnesses, depending on its complexity and is the second most basic weave that can be made on a fairly simple loom.

Twill weave is often designated as a fraction, such as 2⁄1, in which the numerator indicates the number of harnesses that are raised (and thus threads crossed: in this example, two), and the denominator indicates the number of harnesses that are lowered when a filling yarn is inserted (in this example, one). The fraction 2⁄1 is read as "two up, one down" (the fraction for plain weave is 1⁄1.). The minimum number of harnesses needed to produce a twill can be determined by totaling the numbers in the fraction; for the example described, the number of harnesses is three. Twill weave can be identified by its diagonal lines.

Characteristics

Twill fabrics technically have a front and a back side, unlike plain weave, whose two sides are the same. The front side of the twill is called the "technical face," and the back the "technical back." The technical face side of a twill weave fabric is the side with the most pronounced wale; it is usually more durable and more attractive, is most often used as the fashion side of the fabric, and is the side visible during weaving. If there are warp floats on the technical face (i.e. if the warp crosses over two or more wefts), there will be filling floats (the weft will cross over two or more warps) on the technical back. If the twill wale goes up to the right on one side, it will go up to the left on the other side. Twill fabrics have no "up" and "down" as they are woven.

Sheer fabrics are seldom made with a twill weave. Because a twill surface already has interesting texture and design, printed twills (where a design is printed on the cloth) are much less common than printed plain weaves. When twills are printed, this is typically done on lightweight fabrics.

Soiling and stains are less noticeable on the uneven surface of twills than on a smooth surface, such as plain weaves, and as a result twills are often used for sturdy work clothing and for durable upholstery. Denim, for example, is a twill.

The fewer interlacings in twills as compared to other weaves allow the yarns to move more freely, and therefore they are softer and more pliable, and drape better than plain-weave textiles. Twills also recover from creasing better than plain-weave fabrics do. When there are fewer interlacings, the yarns can be packed closer together to produce high-count fabrics. With higher counts, including high-count twills, the fabric is more durable, and is air- and water-resistant.

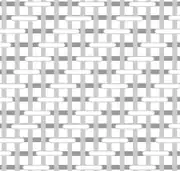

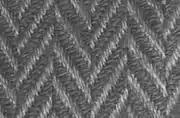

Twills can be divided into even-sided, warp-faced, and weft-faced. Even sided twills have the same amount of warp and weft threads visible on both sides of the fabric. Warp-faced twills have more warp threads visible on the face side, and weft-faced twills have more weft threads visible on the face side.[2] Even-sided twills include foulard or surah, herringbone, houndstooth, serge, sharkskin, and twill flannel. Warp-faced twills include cavalry twill, chino, covert, denim, drill, fancy twill, gabardine, and lining twill.

References

- Oelsner, Gustaf Hermann (1915). A Handbook of Weaves. New York: The Macmillan Company. OCLC 2325693.

- Kiron, Mazharul Islam (2 June 2015). "Twill Weave: Features, Classification, Derivatives and Uses". Textile Learner. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

.svg.png.webp)