USS Swordfish (SSN-579)

USS Swordfish (SSN-579), a Skate-class nuclear-powered submarine, was the second submarine of the United States Navy named for the swordfish, a large fish with a long, swordlike beak and a high dorsal fin.

USS Swordfish | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | USS Swordfish |

| Ordered | 18 July 1955 |

| Builder | Portsmouth Naval Shipyard |

| Laid down | 25 January 1956 |

| Launched | 27 August 1957 |

| Commissioned | 15 September 1958 |

| Decommissioned | 2 June 1989 |

| Stricken | 2 June 1989 |

| Fate | Submarine recycling program |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Skate-class submarine |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 267 ft 7 in (81.56 m) |

| Beam | 25 ft (7.6 m) |

| Draft | 22 ft (6.7 m) |

| Propulsion | S3W reactor |

| Speed | 18 knots (21 mph; 33 km/h) |

| Complement | 87 |

| Armament | 8 × 21 in (530 mm) torpedo tubes (6 forward, 2 aft) |

Construction and commissioning

The contract to build Swordfish was awarded to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard of Kittery, Maine, on 18 July 1955, and her keel was laid down on 25 January 1956. She was launched on 27 August 1957 sponsored by Mrs. Eugene C. Riders, and commissioned on 15 September 1958 with Commander Shannon D. Cramer, Jr., in command.

Service history

1958–1981

Swordfish completed fitting out and held her shakedown in the Atlantic Ocean. After post-shakedown availability and subsequent sea trials along the East Coast, she was assigned a home port at Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, effective 16 March 1959. She steamed to Hawaii in July and was the second nuclear-powered submarine to join the United States Pacific Fleet, joining USS Sargo. Assigned to Submarine Squadron 1, Swordfish steamed over 35,000 miles during her first year in commission with over 80% of them submerged.

In January 1960, Swordfish deployed to the western Pacific Ocean (WestPac) for four months and became the first nuclear submarine in that area. During this time, President of the Republic of China Chiang Kai-shek was embarked for a one-day indoctrination cruise. She deployed to WestPac again on 20 June and on this occasion took President of the Philippines Carlos P. Garcia to sea for a one-day demonstration. The submarine conducted local operations in the Hawaiian area from January to May 1961. In late May, the submarine got underway for the West Coast of the United States where she operated between San Diego and San Francisco, with various Pacific Fleet units. Swordfish returned to Pearl Harbor on 14 July and operated locally until September when she deployed to the western Pacific for two months.

Swordfish sailed to Mare Island in January 1962 and became the first nuclear submarine to be overhauled on the Pacific coast. She returned to Hawaii on 29 September for refresher training and local operations. On 26 October, the submarine was again deployed to WestPac.

In late 1963, Swordfish observed from close range a Soviet anti-submarine warfare exercise in the North Pacific. She was detected, but the Soviets were unable to force her to surface. The mission provided recordings of the Soviets' radio chatter and plots of their radar search patterns. During the same operations Swordfish photographed the first Soviet Yankee-class nuclear-powered submarine being towed from a shipyard to be outfitted in another.

Swordfish continued operating from Pearl Harbor, on local operations and on deployments to the western Pacific, as a member of Submarine Division 71 until 30 June 1965 when she was assigned to Submarine Division 11 which was also based there. In late 1965, Swordfish was awarded a Navy Unit Commendation for special operations from 8 October to 3 December 1963, from 22 September to 25 November 1964, and from 20 May to 23 July 1965.

Swordfish arrived at the San Francisco Naval Shipyard on 1 November 1965 to undergo a refueling and SubSafe overhaul which lasted until 31 August 1967. Sea trials were held in September and weapons trials in early October. She returned to Pearl Harbor on 13 October and conducted refresher training until 31 December 1967. The period 1 January to 2 February 1968 was spent in preparation for overseas movement. Swordfish deployed to the western Pacific on 3 February.

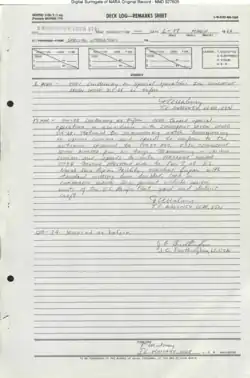

On 8 March 1968, K-129, a Soviet Golf II-class submarine, sank northwest of Oahu. On 17 March, Swordfish put into Yokosuka, Japan, for emergency repairs to a bent periscope. It was suggested by the Soviets that K-129 was lost after a collision with Swordfish.[1] The United States Navy states that Swordfish was damaged in an ice pack in the Sea of Japan, and that K-129 was some 2,000 nautical miles (3,700 km; 2,300 mi) distant from Swordfish when she was lost.

In May 1968, anti-nuclear activists alleged that Swordfish had released radioactive coolant water into the harbor of Sasebo, Japan where she was moored at the time. Some sources state that Japanese scientists discovered levels up to twenty times normal background, others, that they could not detect any increase in radioactivity. The Japanese protested the incident to the United States, and Japanese Premier Eisaku Satō stated that U.S. nuclear ships would no longer be allowed to call at Japanese ports unless their safety could be guaranteed.

Swordfish returned to Pearl Harbor on 5 September and remained in port the remaining four months of the year.

Swordfish conducted local operations in the Hawaiian area from 1 January to 11 May 1969 at which time she again deployed until 4 November. The remainder of the year was spent in a leave and upkeep period. She was deployed on special operations from 24 February to 9 April 1970 and then entered drydock at Pearl Harbor for an availability period which lasted until 30 September. The remainder of calendar year 1970 was spent conducting a period of crew training necessitated by the yard period.

Local operations during 1971 were broken by a tour in WestPac from 24 March to 22 September. During this deployment, the submarine visited Yokosuka, Buckner Bay, Pusan, and Hong Kong. Swordfish continued local operations until 26 June 1972 when she entered the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard for her annual overhaul which lasted through 31 December 1973. Upon completion of the yard period, Swordfish resumed operations with her Pearl Harbor-based squadron.

On 22 June 1977, Swordfish launched a Mark 14 torpedo which made a circular run and hit the port screw. Fortunately, it was an exercise torpedo. Swordfish returned to port for 24 hours, did a screw change, and went back to sea.

Swordfish made a deployment to the western Pacific from October 1977 until March 1978, stopping in Yokosuka, Pusan, Chinhae, Guam, Philippines, and Hong Kong.

In September 1978 a paint scraper worth 15¢ was accidentally dropped into a torpedo launcher and jammed the loading piston in its cylinder. For a week divers tried to free the piston while Swordfish was waterborne but all attempts failed. She had to be dry-docked and subsequent repairs cost $171,000.[2]

In July 1979 the Swordfish began a western Pacific deployment, stopping in Yokosuka, Pusan, and the territory of Guam. After refitting in Guam the ship began operations again, but was forced to return to Guam after several days to repair the diesel engine after the muffler exhaust valve broke, flooding the engine. After repairs were made the deployment continued without incident until the ship's return to Pearl Harbor in December 1979.

Local operations were carried out until the ship was deployed to the western Pacific during the summer of 1980. Upon returning to Pearl Harbor the ship resumed local operations until entering Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard for overhaul and refueling in March 1981.

1985 safety incident

In late October 1985, Swordfish was delayed in departing Pearl Harbor due to the failure of the drain pump. A replacement was obtained from USS Skate, in the shipyard for decommissioning, but Swordfish put to sea before the pump was fully connected and tested, and the crew could not get the pump to operate. Since the engine room bilges could not be pumped, by the evening of 23 October, the first day at sea, the water in the engine room lower level bilge was over the deck plates (more than four feet). The crew tried to use a portable submersible pump, but were not successful.

When the water level got high enough to get up into the bottoms of the motors for the main lube oil pumps, causing grounds, the captain came aft and saw the situation and decided to take the boat shallow to allow pumping bilges. When the planesmen put a slight up-angle on the boat to come shallow the water in the bilges instantly rushed aft, greatly increasing its effect on trim (this is known as "free surface effect", later classes of subs have flood control bulkheads in engineroom lower level to prevent this) and causing an up-angle of about 45 degrees.

When "fire in engineroom lower level" was announced, due to water in the main lube oil pump motors, a man in the aft end of engineroom upper level opened the watertight door into the stern room, which swung into the stern room, to retrieve a fire extinguisher. Just then the up-angle increased dramatically and the bilge water began pouring in. The door was shut before the boat surfaced. With the boat on an even keel, the water came up to the deadlight in the door.

The maneuvering watchstanders began to take the immediate actions for loss of shaft lube oil; the throttleman began to shut the throttles for the main engines. Without propulsion, the extreme up-angle caused the ship to quickly stop and begin moving backwards, sinking stern first. When the fire was announced, the Engineer had gone to Maneuvering (the control center of the engine room). He saw the depth gauge indicating a rapid increase in depth, ordered "Ahead Full" on his own initiative, and opened the starboard forward throttle himself in an effort to drive the ship to the surface. In Control, the Captain saw similar indications, and ordered "Blow Aft!". Before the Chief of the Watch could initiate the blow on the aft group the up-angle became so steep that he was unable to maintain footing and slid to the rear of the Control compartment. He quickly climbed back up to the emergency blow "chicken switches" and opened the after group valve.

Swordfish surfaced successfully. However, during the up-angle the freshwater drain collecting tank vents were submerged and sucked contaminated water into the feed system. The steam generator water could not be analyzed immediately because nucleonics laboratory in the stern room had been inundated by the wave of bilgewater. After a while, the leading ELT found the necessary reagents and analyzed samples from both steam generators on the top hat in reactor compartment upper level. By this time the boat was in direct communication with Naval Reactors, which ordered the reactor shut down and cooled down and steam generators drained and refilled. The emergency diesel generator, located in engineroom lower level, initially had water in the generator from the incident but it was drained and the diesel was online before the reactor was shut down. The reactor was cooled down and steam generators were blown down with service air and refilled until all fresh water on the boat was exhausted, which was a couple of hours before arriving back in Pearl Harbor. Subsequent analysis of steam generator water revealed no leakage of reactor coolant into the steam generators.

Three of the boat's four air conditioning compressors were shut down as part of the rig for reduced electrical. The temperature in the ship exceeded 80 °F (27 °C) with near 100% humidity for the several hours required for a tugboat to be dispatched from Pearl Harbor and tow Swordfish home. The tugboat USS Reclaimer (ARS-42) arrived the next morning and began the tow around noon, arriving in Pearl Harbor just after midnight.

The actions of the chief of the watch and the engineer saved Swordfish and her crew. The boat spent the rest of 1985 in port making repairs and returned to sea in January 1986, making a successful deployment to the western Pacific later in 1986.

Decommissioning and disposal

Swordfish was decommissioned and stricken from the Naval Vessel Registry on 2 June 1989. Her disposal through the Ship-Submarine Recycling Program (SRP) was completed at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard at Bremerton, Washington, on 11 September 1995.

Honors and awards

- Navy Unit Commendation with seven stars (8 awards)

- Meritorious Unit Commendation with star (2 awards)

Navy "E" Ribbon (2 awards)

Navy "E" Ribbon (2 awards) Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal- Vietnam Service Medal with four campaign stars for Vietnam War service

Swordfish also received a number of classified awards.

K-129 incident legacy

Russia has repeatedly requested copies of Swordfish's logs to trace her at the time K-129 was lost, but the Pentagon refuses to release them; Swordfish was involved in highly sensitive operations at that time. The United States has salvaged some parts of K-129, and has provided the Russian government with a videotape of a burial-at-sea ceremony for six K-129 crew members whose remains were recovered when the American deep-sea drillship Hughes Glomar Explorer recovered parts of K-129 in 1974.

References

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- Offley, Ed Scorpion Down: Sunk by the Soviets, Buried by the Pentagon (Paperback – 24 Mar 2008)

- Stephen Pile, Bill Tidy, The Book of Heroic Failures, Futura Publications, 1980, p. 170