Uele District

Uele District (French: District de l'Uele, Dutch: District Uele) was a district of the Congo Free State and the Belgian Congo. It roughly corresponded to the current provinces of Bas-Uélé and Haut-Uélé.

Uele District | |

|---|---|

District | |

Uele District | |

| Coordinates: 4.006479°N 26.632268°E | |

| Country | Belgian Congo |

| Province | Orientale |

| District | Uele |

Landscape

The Uele District, shown as the Uellé District on an 1897 map of the Congo Free State, was named after the Uele River. The river flows though the district and further west joins the Mbomou River (or Bomu River) to form the Ubangi River, which defined the northeastern border of the Belgian Congo.[1] The French colonies were to the north of the district and the British-controlled Lado Enclave to the east, on the west bank of the Nile. To the west were the Ubangi and Bangala districts, and to the south were the Aruwimi and Stanley Falls districts.[1]

A 1956 description of the district said the north of Uele is covered with shrub savannas interspersed with galleries and fragments of forest. Savannas with Encephalartos septentrionalis occupy the central part while the east and west are characterized by savannas of Lophira. The southern part of the District is covered by a dryland rain forest of Macrolobium (Gilbertiodendron dewevrei). Its boundary with the northern savannas lies a little north of the Uele then approximately follows the Bomokandi River. Along this boundary the forest is marked by deep anthropogenic alterations.[2]

The forest region is a gently undulating plain with a slight slope to the southwest towards the center of the basin. The northern grassy plain has better marked valleys. Rocky sills and rapids cut the streams, which can be dammed.[3] From 400 metres (1,300 ft) at Aketi, the altitude gradually rises to the north and east to reach 650 metres (2,130 ft) at Ango and over 800 metres (2,600 ft) in the east.[4]

Pre-colonial era

Peoples such as the Azande and Mangbetu migrated into the Uele region long before the Europeans arrived. The Ababua and most of the Azande live in the lower Uele, while the Logo and Bodo, and most of the Mangbetu live in the upper Uele.[5]

There do not seem to have been any strong connections with the Arabs or Nubians of Sudan until around 1860, when traders started to visit in search of slaves and ivory. Some of the local chiefs welcomed the traders, while others fought them.[6] Arabic speakers in the region included Egyptian government representatives, traders, soldiers and Faqīhs. Some Azande worked for the Sudanese merchants or even visited Sudan, either voluntarily or as slaves.[7] Some of the local chiefs became Muslims, and styled themselves sultans. The conversions were not always sincere, but some took the religion very seriously and abstained from alcohol, fasted during Ramadan, prayed and adopted Arabic dress.[8] Charles de la Kethulle, who spent two years in the Zande town of Rafaï, wrote in an 1895 article Le sultanat de Rafaï (Le Congo illustré) that almost all the inhabitants could speak Arabic, including the sultan, chiefs and soldiers.[7]

The first Europeans to reach the Uele region were the German botanist and ethnologist Georg August Schweinfurth, who discovered the Uele River in 1870, and the Italian Giovanni Miani. In 1871 Wilhelm Junker (1840–1892), a Russian explorer of German origins, explored the Bomu-Uele region thoroughly. These visitors entered from the north or the east rather than the Congo River.[9] In the 1870s the Egyptians decided to strengthen their control of the Bahr al-Ghazal and of the slave and ivory traders operating from there. Around 1880 many Azande chiefs placed themselves at the disposal of the Egyptians, who were represented by Europeans such as Frank Lupton and Romolo Gessi, in part to fight the slavers. The uprising of Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi, against the Egyptian government in 1881 weakened the influence of the Arabs.[10]

Congo Free State

Exploration

By 1896 King Leopold II of Belgium was becoming concerned that instability in the Bahr al-Ghazal would affect his Congo Free State, and that Sudanese slavers would penetrate further south and join up with the Arab and Swahili traders at Stanley Falls. In January 1888 Alphonse van Gèle explored the Bomu River and part of the Uele river.[10] Leopold's decree of 1 August 1888 divided the Congo Free State into eleven districts, including Aruwimi-Uele with its headquarters in Basoko.[11] Vangèle was instructed to explore the Ubangi River in 1889 and claim land for Leopold II.[12] He was also told to "exploit the ivory of the state domain", and his journal includes many details of tusks he bought or was given by chiefs along the Ubangi, M'bomu and Uele rivers. He had obtained twelve tons of ivory by September 1890.[13]

Jérôme Becker met Sultan Djabir at Basoko in December 1889, and in January 1890 reached Jabir's sultanate.[14] In 1890 the Belgian officers Léon Roget and Jules Alexandre Milz travelled up the Itimbiri River from Bumba, then up the Likati River, reached the Uele River in the region of Djabir and descended it almost to its junction with the Mbomou River.[15] Roget, Milz and Duvivier founded the first Belgian post in the Uele at Djabir in April 1890.[14] This route opened access to the Uele region, although it crossed the territory of the Budja people, who had yet to be pacified. In 1891 Guillaume Van Kerkhoven, Pierre Ponthier and Jules Milz followed the same route to the Uele, then explored the Kibali and the Zoro. They reached the Nile, but had to retreat to the Dungu region when they were attacked by Mahdists.[15] In 1891 Georges Le Marinel ascended the Bomu River.[15]

Ernest De Baert was appointed State Inspector of the Haut-Uele expedition in 1892. He was instructed to ensure that all the ivory and rubber of the sultanates of the M’bomu region was paid as tribute to the Free State.[13] By 1892 the Belgians were taking drastic action to prevent ivory and rubber from being smuggled across the M'Bomu to French Territory. They stationed soldiers in each marketplace who shot anyone who tried to cross the river. However, these efforts were ineffective and much ivory from Uele reached the European companies in Abiras.[16]

The Uele was clearly a natural defensive line for the north of the Congo Free State, and the forests along it would provide a source of food. The authorities decided to build a line of fortified positions along the river. Posts included Yakoma in the Ubangi District, Djabir, Libokwa, Bambili, Surango, Niangara, Dungu and Faradje. Later these posts were connected by the first road in the Congo Free State that could be used by motor vehicles, which was extended from Faradje to the Nile by way of Yei and Loka in the savannah zone.[15] The two posts of Yei and Loka were established to the northeast of Faradje in the arid Lado Enclave on the Nile, leased from the British. The Belgians carried a boat to the Nile in sections, the Van de Kerckhoven, which they assembled and launched on the Nile.[17]

In 1894 Léon Hanolet ascended the Bari River, a right tributary of the Bomu while Théodore Nilis and Charles de la Kethulle ascended the Chinko River, another tributary of the Bomu.[15] The Belgian expeditions caused a dispute with the French that led to an agreement that the Bomu would be the northern border of the Congo Free State in this region.[18] Another route to the Uele went from Basoko up the Aruwimi River to Bomili, then up the Nepoko River, across to the Duru post on the Bomokandi River, and on to the Dungu post. Much of this route was by foot, since the rivers were impassible.[17] In 1895 Aruwimi-Uele District was divided into Aruwimi District and Uele District.[11]

Occupation

)_(18134278166).jpg.webp)

At first, some of the sultans were friendly. Later, as the Belgians strengthened their grip, some such as Engwetra in 1896 rose in rebellion. Others found that by treaty their land was now French or British, or chose to move to French territory.[14] In 1895 Jules Joseph La Haye was charged with building the Bomokandi post on the rocky right bank of the Uele River. On 10 January 1896 he met Louis-Napoléon Chaltin, who was undertaking an expedition against Bili. Chaltin and La Haye decided to move the Bomokandi post to the left bank of the river, 20' upstream.[19] The expedition of Chaltin in 1896, assisted by 700 lancers provided by Sultan Renzi, fought the battles of Bedden and Redjaf. The Mahdists were defeated and the city of Redjaf was captured.[17]

After taking leave in Europe La Haye returned to Uele, where he was appointed district commissioner on 16 May 1897. Between 4 July 1900 and 16 January 1901 Verstraeten replaced him as district commissioner while he took leave in Europe. On his return La Haye led an expedition of 600 men against the Ababua, who had rebelled. The rebels were destroyed at the end of June 1901. On 3 July 1902 La Haye was shot and killed while sleeping in Kodia village.[19]

On 29 September 1903 the district of Uele was divided into five administrative zones:[20]

| Zone | Former name | Headquarters |

|---|---|---|

| Uere-Bili | Uere-Bomu | Bomokandi |

| Gurba-Dungu | Makrakra | Dungu |

| Rubi | Rubi-Uele | Buta |

| Bomokandi | Makua | To be created on the Bomokandi near the old Nala post |

| Lado enclave | Lado enclave | Lado |

Rubber was harvested in the Uele District, and taken to the port of Bumba for storage and transport by river to Bas-Congo.[21] A single Catholic mission was established at Gombari on the Bomokandi River.[22] The administration responded to an epidemic of sleeping sickness that began in 1904 in the Congo Free State with measures that had been proven against cholera and plague in Europe. Between 1904 and 1914 they placed those who were infected or suspected of being infected in isolation camps or lazarets, and mapped out the zones of infection. Many of the local people in Uele District saw the health campaign as another aspect of the program of conquest and exploitation.[23] The director of Ibembo lazaret made several proposals between 1907 and 1912 for a program to contain sleeping sickness in the "great uninfected triangle" of the Uele. The military campaign against Sasa,[lower-alpha 1] the powerful leader of the Azande, exposed the true extent of the disease. It was found that sleeping sickness was widespread in the north of Uele District.[25] The district was to have been opened to free trade in July 1912, and flooded by mineral prospectors, traders and their porters.[26]

Belgian Congo

The Congo Free State was annexed by Belgium as the Belgian Congo in 1908.[27] On 1 July 1910 a court of first instance was established at Niangara to serve Uele District, one of seven in the colony.[28] The Uele District was divided into Bas-Uele (Lower Uele) and Haut-Uele (Upper Uele) by an arrêté royal of 28 March 1912, which divided the Congo into 22 districts.[29] In a major reform in 1914 these were incorporated into the Orientale Province.[30][31] In the reorganization of 1933 Bas-Uele and Haut-Uele were reunited into Uele District, now part of the Stanleyville Province, with some territory to the east transferred to the Kibali-Ituri District.[32] Stanleyville Province was renamed Orientale/Oost Province in 1947.[27]

During the colonial era a railway was constructed through the region from east to west, on which the agricultural road network converged. The railway carried products from Uele and Ituri to Bumba, from where it was taken to Léopoldville, Boma, and on to Europe.[5]

In 1947 Uele District had its headquarters in Buta. The territories were Bondo, Ango, Dungu, Manbetu (headquarters in Paulis), Buta, Aketi, Poko and Niangara.[33] The estimated total populations was 795,721.[34] In 1956 the population was:[35]

| Territory | Population | Density/km2 |

|---|---|---|

| Paulis | 132,517 | 14.18 |

| Dungu | 126,493 | 3.89 |

| Buta | 125,641 | 4.61 |

| Poko | 118,696 | 5.18 |

| Bondo | 99,879 | 2.62 |

| Aketi | 82,596 | 3.25 |

| Niangara | 65,574 | 7.12 |

| Ango | 62,266 | 1.79 |

| Total | 813,662 | 4.08 |

The population was concentrated along the axis from Paulis to Aketi.[35] A 1955–1957 map showed that Uele District had once more been divided into Bas-Uele and Haut-Uele.[36]

Post-independence

In 1962 Orientale Province was broken up into Kibali-Ituri, Uélé and Haut-Congo provinces.[27] Uele had its capital in Isiro.[5] The heads of Uélé Province were:[27]

| Start | End | Officeholder | Title |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 September 1962 | May 1965 | Paul Mambaya | President |

| 6 July 1965 | 28 December 1966 | François Kupa | Governor |

Orientale Province was reconstituted in 1966.[27] As of 2014 Bas-Uele had the lowest population density in the country, with 5 or 6 people per km2, while Haut-Uele had 13 people per km2.[5] In 2015 Orientale was broken into the province into the provinces of Bas-Uélé, Haut-Uélé, Ituri and Tshopo.[27]

Maps

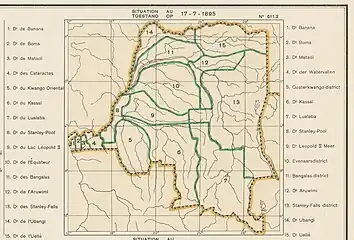

Districts of the Congo Free State in 1895

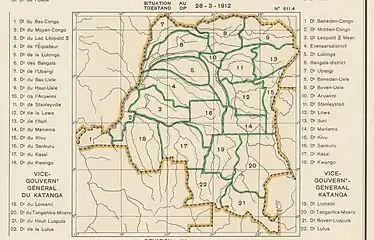

Districts of the Congo Free State in 1895 1912 provinces and districts

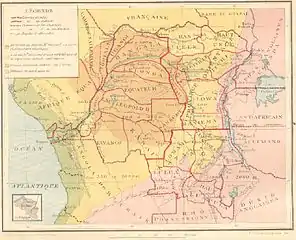

1912 provinces and districts 1914 districts

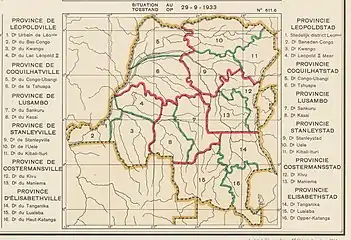

1914 districts 1933 provinces and districts

1933 provinces and districts

_-_Bas-Uele.svg.png.webp) Current province of Bas-Uele

Current province of Bas-Uele_-_Haut-Uele.svg.png.webp) Current province of Haut-Uele

Current province of Haut-Uele

Notes

- Sasa was the last important Zande Sultan. In 1912 he was captured and deported to Boma, at the mouth of the Congo.[24]

References

- Omasombo Tshonda 2015, p. 16.

- Depasse 1956, p. 4–5.

- Depasse 1956, p. 5.

- Depasse 1956, p. 6.

- Omasombo Tshonda 2014, p. 7.

- Luffin 2004, p. 147.

- Luffin 2004, p. 151.

- Luffin 2004, p. 150.

- Ergo 2013, p. 1.

- Luffin 2004, p. 148.

- Omasombo Tshonda 2014, p. 211.

- Bas De Roo 2014, p. 119.

- Bas De Roo 2014, p. 120.

- Luffin 2004, p. 149.

- Ergo 2013, p. 2.

- Bas De Roo 2014, p. 132.

- Ergo 2013, p. 3.

- Ergo 2013, pp. 2–3.

- Coosemans 1946, p. col497–499.

- Arrêté du Gouverneur Général 1903.

- Ergo 2013, p. 5.

- Ergo 2013, p. 7.

- Lyons 1985, p. 69.

- Luffin 2004, p. 155.

- Lyons 2002, p. 130.

- Lyons 2002, p. 132.

- Congo (Kinshasa) Provinces.

- Albert, Roi des Belges 1910.

- Lemarchand 1964, p. 63.

- Lemarchand 1964, pp. 63–64.

- Roland & Duchesne 1914.

- Atlas général du Congo.

- La Population et ses Besoins, p. 6.

- La Population et ses Besoins, p. 9.

- Depasse 1956, p. 3.

- Brass 2015, p. 243.

Sources

- Albert, Roi des Belges (1 July 1910), Décret du 1er Juillet 1910 (PDF), retrieved 2020-08-28

- Arrêté du Gouverneur Général Général du 29 Septembre 1903 (PDF) (in French), retrieved 2020-08-28

- Atlas général du Congo / Algemene atlas van Congo (in French and Dutch), Belgium: Institut Royal Colonial Belge, 1948–1963, OCLC 681334449 / http://www.kaowarsom.be/en/online_maps

- Bas De Roo (2014), "Customs and Contraband in the Congolese M'Bomu Region" (PDF), Journal of Belgian History, retrieved 2020-08-28

- Brass, William (8 December 2015), Demography of Tropical Africa, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-4008-7714-0, retrieved 20 August 2020

- "Congo (Kinshasa) Provinces", Rulers.org, retrieved 2020-08-05

- Coosemans, M. (28 September 1946), Biographie Coloniale Belge (PDF) (in French), vol. I, Inst. roy. colon. belge, retrieved 2020-08-27

- Depasse, P. (1956), "Monographie Piscicole de la Province Orientale" (PDF), Bulletin Agricole du Congo Belge (in French), XLVII (4), retrieved 2020-08-28

- Ergo, André-Bernard (2013), "Les postes fortifiés de la frontière Nord de l'État Indépendant du Congo" (PDF), Histoire du Congo, retrieved 2020-08-27

- La Population et ses Besoins (PDF), 1948, retrieved 2020-08-27

- Lemarchand, René (1964), Political Awakening in the Belgian Congo, University of California Press, GGKEY:TQ2J84FWCXN, retrieved 19 August 2020

- Luffin, Xavier (2004), "The Use Of Arabic As A Written Language In Central Africa The Case Of The Uele Basin (Northern Congo) In The Late Nineteenth Century" (PDF), Sudanic Africa, 15: 145–177, retrieved 2020-08-27

- Lyons, Maryinez (6 June 2002), The Colonial Disease: A Social History of Sleeping Sickness in Northern Zaire, 1900-1940, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-52452-0, retrieved 28 August 2020

- Lyons, M. (1985), "From 'Death Camps' to Cordon Sanitaire: The Development of Sleeping Sickness Policy in the Uele District of the Belgian Congo, 1903–1914", The Journal of African History, 26 (1): 69–91, doi:10.1017/S0021853700023094, PMID 11617235, S2CID 9787086, retrieved 2020-08-27

- Omasombo Tshonda, Jean (2014), Bas-Uele, Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale, ISBN 978-9-4916-1586-3, retrieved 2020-08-26

- Omasombo Tshonda, Jean (2015), Mongala : Jonction des territoires et bastion d'une identité supra-ethnique (PDF), Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale, ISBN 978-9-4922-4416-1, retrieved 2020-08-18

- Roland, J.; Duchesne, E. (1914), "Congo Belge, Administrative (1914)", Le Congo Belge, Namur: Wesmael-Charlier