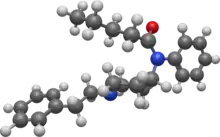

Valerylfentanyl

Valerylfentanyl is an opioid analgesic that is an analog of fentanyl and has been sold online as a designer drug.[1] It has been seldom reported on illicit markets and there is little information about it, though it is believed to be less potent than butyrfentanyl but more potent than benzylfentanyl.[2] In one study, it fully substituted for oxycodone and produced antinociception and oxycodone-like discriminative stimulus effects comparable in potency to morphine in mice,[3] but failed to stimulate locomotor activity in mice at doses up to 100 mg/kg.[4]

| |

| |

| Legal status | |

|---|---|

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C24H32N2O |

| Molar mass | 364.533 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Side effects

Side effects of fentanyl analogs are similar to those of fentanyl itself, which include itching, nausea and potentially serious respiratory depression, which can be life-threatening. Fentanyl analogs have killed hundreds of people throughout Europe and the former Soviet republics since the most recent resurgence in use began in Estonia in the early 2000s, and novel derivatives continue to appear.[5] A new wave of fentanyl analogues and associated deaths began in around 2014 in the US, and have continued to grow in prevalence; especially since 2016 these drugs have been responsible for hundreds of overdose deaths every week.[6]

Legal status

Valerylfentanyl is a Schedule I controlled drug in the USA since 1 February 2018.[7]

In December of 2019, the UNODC announced scheduling recommendations placing valerylfentanyl into Schedule I.[8]

References

- Cooman, Travon; Hoover, Brianna; Sauvé, Brianna; Bergeron, Sadie A.; Quinete, Natalia; Gardinali, Piero; Arroyo, Luis E. (February 2022). "The metabolism of valerylfentanyl using human liver microsomes and zebrafish larvae". Drug Testing and Analysis. 14 (6): 1116–1129. doi:10.1002/dta.3233. ISSN 1942-7611. PMID 35128825. S2CID 246633284.

- Prekupec, Matthew P.; Mansky, Peter A.; Baumann, Michael H. (2017). "Misuse of Novel Synthetic Opioids". Journal of Addiction Medicine. 11 (4): 256–265. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000324. PMC 5537029. PMID 28590391.

- Walentiny, D. Matthew; Moisa, Léa T.; Beardsley, Patrick M. (15 May 2019). "Oxycodone-like discriminative stimulus effects of fentanyl-related emerging drugs of abuse in mice". Neuropharmacology. 150: 210–216. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.02.007. ISSN 0028-3908. PMID 30735691.

- Varshneya, Neil B.; Walentiny, D. Matthew; Moisa, Lea T.; Walker, Teneille D.; Akinfiresoye, Luli R.; Beardsley, Patrick M. (1 June 2019). "Opioid-like antinociceptive and locomotor effects of emerging fentanyl-related substances". Neuropharmacology. 151: 171–179. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.03.023. ISSN 0028-3908. PMC 8992608. PMID 30904478. S2CID 84182661.

- Jane Mounteney; Isabelle Giraudon; Gleb Denissov; Paul Griffiths (July 2015). "Fentanyls: Are we missing the signs? Highly potent and on the rise in Europe". International Journal of Drug Policy. 26 (7): 626–631. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.04.003. PMID 25976511.

- Armenian P, Vo KT, Barr-Walker J, Lynch KL (2017). "Fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and novel synthetic opioids: A comprehensive review". Neuropharmacology. 134 (Pt A): 121–132. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.10.016. PMID 29042317. S2CID 21404877.

- "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Temporary Placement of Seven Fentanyl-Related Substances in Schedule I". Federal Register. 1 February 2018.

- "December 2019 – WHO: World Health Organization recommends 12 NPS for scheduling".