Vampire

A vampire is a mythical creature that subsists by feeding on the vital essence (generally in the form of blood) of the living. In European folklore, vampires are undead creatures that often visited loved ones and caused mischief or deaths in the neighbourhoods which they inhabited while they were alive. They wore shrouds and were often described as bloated and of ruddy or dark countenance, markedly different from today's gaunt, pale vampire which dates from the early 19th century. Vampiric entities have been recorded in cultures around the world; the term vampire was popularized in Western Europe after reports of an 18th-century mass hysteria of a pre-existing folk belief in Southeastern and Eastern Europe that in some cases resulted in corpses being staked and people being accused of vampirism. Local variants in Southeastern Europe were also known by different names, such as shtriga in Albania, vrykolakas in Greece and strigoi in Romania.

In modern times, the vampire is generally held to be a fictitious entity, although belief in similar vampiric creatures (such as the chupacabra) still persists in some cultures. Early folk belief in vampires has sometimes been ascribed to the ignorance of the body's process of decomposition after death and how people in pre-industrial societies tried to rationalize this, creating the figure of the vampire to explain the mysteries of death. Porphyria was linked with legends of vampirism in 1985 and received much media exposure, but has since been largely discredited.[1]

The charismatic and sophisticated vampire of modern fiction was born in 1819 with the publication of "The Vampyre" by the English writer John Polidori; the story was highly successful and arguably the most influential vampire work of the early 19th century. Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula is remembered as the quintessential vampire novel and provided the basis of the modern vampire legend, even though it was published after fellow Irish author Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu's 1872 novel Carmilla. The success of this book spawned a distinctive vampire genre, still popular in the 21st century, with books, films, television shows, and video games. The vampire has since become a dominant figure in the horror genre.

Etymology and word distribution

The term "vampire" is the earliest recorded in English, Latin and French and they refer to vampirism in Russia, Poland and North Macedonia.[2] The English term was derived (possibly via French vampyre) from the German Vampir, in turn derived in the early 18th century from the Serbian вампир (vampir).[3][4][5] The Serbian form has parallels in virtually all Slavic and Turkic languages: Bulgarian and Macedonian вампир (vampir), Turkish: Ubır, Obur, Obır, Tatar language: Убыр (Ubır), Chuvash language: Вупăр (Vupăr), Bosnian: вампир (vampir), Croatian vampir, Czech and Slovak upír, Polish wąpierz, and (perhaps East Slavic-influenced) upiór, Ukrainian упир (upyr), Russian упырь (upyr'), Belarusian упыр (upyr), from Old East Slavic упирь (upir') (many of these languages have also borrowed forms such as "vampir/wampir" subsequently from the West; these are distinct from the original local words for the creature). The exact etymology is unclear.[6][7] In Albanian the words lu(v)gat and dhampir are used; the latter seems to be derived from the Gheg Albanian words dham 'tooth' and pir 'to drink'.[8][7] The origin of the modern word Vampire (Upiór means Hortdan, Vampire or Witch in Turkic and Slavic myths.) comes from the term Ubir-Upiór, the origin of the word Ubir or Upiór is based on the regions around the Volga (Itil) River and Pontic steppes. Upiór myht is through the migrations of the Kipchak-Cuman people to the Eurasian steppes allegedly spread. The modern word "Vampire" is derived from the Old Slavic and Turkic languages form "онпыр (onpyr)", with the addition of the "v" sound in front of the large nasal vowel (on), characteristic of Old Bulgarian. The Bulgarian format is впир (vpir). (other names: onpyr, vopir, vpir, upir, upierz.)[9][10]

Czech linguist Václav Machek proposes Slovak verb vrepiť sa 'stick to, thrust into', or its hypothetical anagram vperiť sa (in Czech, the archaic verb vpeřit means 'to thrust violently') as an etymological background, and thus translates upír as 'someone who thrusts, bites'.[11] The term was introduced to German readers by the Polish Jesuit priest Gabriel Rzączyński in 1721.[12] An early use of the Old Russian word is in the anti-pagan treatise "Word of Saint Grigoriy" (Russian Слово святого Григория), dated variously to the 11th–13th centuries, where pagan worship of upyri is reported.[13][14]

The word vampire (as vampyre) first appeared in English in 1732, in news reports about vampire "epidemics" in eastern Europe.[15][lower-alpha 1] After Austria gained control of northern Serbia and Oltenia with the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718, officials noted the local practice of exhuming bodies and "killing vampires".[17] These reports, prepared between 1725 and 1732, received widespread publicity.[17][18]

Folk beliefs

The notion of vampirism has existed for millennia. Cultures such as the Mesopotamians, Hebrews, Ancient Greeks, Manipuri and Romans had tales of demons and spirits which are considered precursors to modern vampires. Despite the occurrence of vampiric creatures in these ancient civilizations, the folklore for the entity known today as the vampire originates almost exclusively from early 18th-century southeastern Europe,[19] when verbal traditions of many ethnic groups of the region were recorded and published. In most cases, vampires are revenants of evil beings, suicide victims, or witches, but they can also be created by a malevolent spirit possessing a corpse or by being bitten by a vampire. Belief in such legends became so pervasive that in some areas it caused mass hysteria and even public executions of people believed to be vampires.[20]

Description and common attributes

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

It is difficult to make a single, definitive description of the folkloric vampire, though there are several elements common to many European legends. Vampires were usually reported as bloated in appearance, and ruddy, purplish, or dark in colour; these characteristics were often attributed to the recent drinking of blood, which was often seen seeping from the mouth and nose when one was seen in its shroud or coffin, and its left eye was often open.[21] It would be clad in the linen shroud it was buried in, and its teeth, hair, and nails may have grown somewhat, though in general fangs were not a feature.[22] Chewing sounds were reported emanating from graves.[23]

Creating vampires

The causes of vampiric generation were many and varied in original folklore. In Slavic and Chinese traditions, any corpse that was jumped over by an animal, particularly a dog or a cat, was feared to become one of the undead.[24] A body with a wound that had not been treated with boiling water was also at risk. In Russian folklore, vampires were said to have once been witches or people who had rebelled against the Russian Orthodox Church while they were alive.[25]

In Albanian folklore, the dhampir is the hybrid child of the karkanxholl (a lycanthropic creature with an iron mail shirt) or the lugat (a water-dwelling ghost or monster). The dhampir sprung of a karkanxholl has the unique ability to discern the karkanxholl; from this derives the expression the dhampir knows the lugat. The lugat cannot be seen, he can only be killed by the dhampir, who himself is usually the son of a lugat. In different regions, animals can be revenants as lugats; also, living people during their sleep. Dhampiraj is also an Albanian surname.[26]

Prevention

Cultural practices often arose that were intended to prevent a recently deceased loved one from turning into an undead revenant. Burying a corpse upside-down was widespread, as was placing earthly objects, such as scythes or sickles,[27] near the grave to satisfy any demons entering the body or to appease the dead so that it would not wish to arise from its coffin. This method resembles the ancient Greek practice of placing an obolus in the corpse's mouth to pay the toll to cross the River Styx in the underworld. The coin may have also been intended to ward off any evil spirits from entering the body, and this may have influenced later vampire folklore. This tradition persisted in modern Greek folklore about the vrykolakas, in which a wax cross and piece of pottery with the inscription "Jesus Christ conquers" were placed on the corpse to prevent the body from becoming a vampire.[28]

Other methods commonly practised in Europe included severing the tendons at the knees or placing poppy seeds, millet, or sand on the ground at the grave site of a presumed vampire; this was intended to keep the vampire occupied all night by counting the fallen grains,[29][30] indicating an association of vampires with arithmomania. Similar Chinese narratives state that if a vampiric being came across a sack of rice, it would have to count every grain; this is a theme encountered in myths from the Indian subcontinent, as well as in South American tales of witches and other sorts of evil or mischievous spirits or beings.[31]

Identifying vampires

Many rituals were used to identify a vampire. One method of finding a vampire's grave involved leading a virgin boy through a graveyard or church grounds on a virgin stallion—the horse would supposedly balk at the grave in question.[25] Generally a black horse was required, though in Albania it should be white.[32] Holes appearing in the earth over a grave were taken as a sign of vampirism.[33]

Corpses thought to be vampires were generally described as having a healthier appearance than expected, plump and showing little or no signs of decomposition.[34] In some cases, when suspected graves were opened, villagers even described the corpse as having fresh blood from a victim all over its face.[35] Evidence that a vampire was active in a given locality included death of cattle, sheep, relatives or neighbours. Folkloric vampires could also make their presence felt by engaging in minor poltergeist-styled activity, such as hurling stones on roofs or moving household objects,[36] and pressing on people in their sleep.[37]

Protection

Apotropaics—items able to ward off revenants—are common in vampire folklore. Garlic is a common example;[40] a branch of wild rose and hawthorn are sometimes associated with causing harm to vampires, and in Europe, mustard seeds would be sprinkled on the roof of a house to keep them away.[41] Other apotropaics include sacred items, such as crucifix, rosary, or holy water. Some folklore also states that vampires are unable to walk on consecrated ground, such as that of churches or temples, or cross running water.[39]

Although not traditionally regarded as an apotropaic, mirrors have been used to ward off vampires when placed, facing outwards, on a door (in some cultures, vampires do not have a reflection and sometimes do not cast a shadow, perhaps as a manifestation of the vampire's lack of a soul).[42] This attribute is not universal (the Greek vrykolakas/tympanios was capable of both reflection and shadow), but was used by Bram Stoker in Dracula and has remained popular with subsequent authors and filmmakers.[43]

Some traditions also hold that a vampire cannot enter a house unless invited by the owner; after the first invitation they can come and go as they please.[42] Though folkloric vampires were believed to be more active at night, they were not generally considered vulnerable to sunlight.[43]

Reports in 1693 and 1694 concerning citings of vampires in Poland and Russia claimed that when a vampire's grave was recognized, eating bread baked with its blood mixed into the flour,[44] or simply drinking it, granted the possibility of protection. Other stories (primarily the Arnold Paole case) claimed the eating of dirt from the vampire's grave would have the same effect.[45]

Methods of destruction

Methods of destroying suspected vampires varied, with staking the most commonly cited method, particularly in South Slavic cultures.[47] Ash was the preferred wood in Russia and the Baltic states,[48] or hawthorn in Serbia,[49] with a record of oak in Silesia.[50][51] Aspen was also used for stakes, as it was believed that Christ's cross was made from aspen (aspen branches on the graves of purported vampires were also believed to prevent their risings at night).[52] Potential vampires were most often staked through the heart, though the mouth was targeted in Russia and northern Germany[53][54] and the stomach in north-eastern Serbia.[55] Piercing the skin of the chest was a way of "deflating" the bloated vampire. This is similar to a practice of "anti-vampire burial": burying sharp objects, such as sickles, with the corpse, so that they may penetrate the skin if the body bloats sufficiently while transforming into a revenant.[56]

Decapitation was the preferred method in German and western Slavic areas, with the head buried between the feet, behind the buttocks or away from the body.[47] This act was seen as a way of hastening the departure of the soul, which in some cultures was said to linger in the corpse. The vampire's head, body, or clothes could also be spiked and pinned to the earth to prevent rising.[57]

Romani people drove steel or iron needles into a corpse's heart and placed bits of steel in the mouth, over the eyes, ears and between the fingers at the time of burial. They also placed hawthorn in the corpse's sock or drove a hawthorn stake through the legs. In a 16th-century burial near Venice, a brick forced into the mouth of a female corpse has been interpreted as a vampire-slaying ritual by the archaeologists who discovered it in 2006.[59] In Bulgaria, over 100 skeletons with metal objects, such as plough bits, embedded in the torso have been discovered.[58]

Further measures included pouring boiling water over the grave or complete incineration of the body. In Southeastern Europe, a vampire could also be killed by being shot or drowned, by repeating the funeral service, by sprinkling holy water on the body, or by exorcism. In Romania, garlic could be placed in the mouth, and as recently as the 19th century, the precaution of shooting a bullet through the coffin was taken. For resistant cases, the body was dismembered and the pieces burned, mixed with water, and administered to family members as a cure. In Saxon regions of Germany, a lemon was placed in the mouth of suspected vampires.[60]

Ancient beliefs

.jpg.webp)

Tales of supernatural beings consuming the blood or flesh of the living have been found in nearly every culture around the world for many centuries.[61] The term vampire did not exist in ancient times. Blood drinking and similar activities were attributed to demons or spirits who would eat flesh and drink blood; even the devil was considered synonymous with the vampire.[62] Almost every culture associates blood drinking with some kind of revenant or demon, or in some cases a deity. In India tales of vetālas, ghoulish beings that inhabit corpses, have been compiled in the Baitāl Pacīsī; a prominent story in the Kathāsaritsāgara tells of King Vikramāditya and his nightly quests to capture an elusive one.[63] Piśāca, the returned spirits of evil-doers or those who died insane, also bear vampiric attributes.[64]

The Persians were one of the first civilizations to have tales of blood-drinking demons: creatures attempting to drink blood from men were depicted on excavated pottery shards.[65] Ancient Babylonia and Assyria had tales of the mythical Lilitu,[66] synonymous with and giving rise to Lilith (Hebrew לילית) and her daughters the Lilu from Hebrew demonology. Lilitu was considered a demon and was often depicted as subsisting on the blood of babies,[66] and estries, female shapeshifting, blood-drinking demons, were said to roam the night among the population, seeking victims. According to Sefer Hasidim, estries were creatures created in the twilight hours before God rested. An injured estrie could be healed by eating bread and salt given to her by her attacker.[67]

Greco-Roman mythology described the Empusae,[68] the Lamia,[69] the Mormo[70] and the striges. Over time the first two terms became general words to describe witches and demons respectively. Empusa was the daughter of the goddess Hecate and was described as a demonic, bronze-footed creature. She feasted on blood by transforming into a young woman and seduced men as they slept before drinking their blood.[68] The Lamia preyed on young children in their beds at night, sucking their blood, as did the gelloudes or Gello.[69] Like the Lamia, the striges feasted on children, but also preyed on adults. They were described as having the bodies of crows or birds in general, and were later incorporated into Roman mythology as strix, a kind of nocturnal bird that fed on human flesh and blood.[71]

Medieval and later European folklore

Many myths surrounding vampires originated during the medieval period. The 12th-century British historians and chroniclers Walter Map and William of Newburgh recorded accounts of revenants,[20][72] though records in English legends of vampiric beings after this date are scant.[73] The Old Norse draugr is another medieval example of an undead creature with similarities to vampires.[74] Vampiric beings were rarely written about in Jewish literature; the 16th-century rabbi David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra (Radbaz) wrote of an uncharitable old woman whose body was unguarded and unburied for three days after she died and rose as a vampiric entity, killing hundreds of people. He linked this event to the lack of a shmirah (guarding) after death as the corpse could be a vessel for evil spirits.[75]

In 1645, the Greek librarian of the Vatican, Leo Allatius, produced the first methodological description of the Balkan beliefs in vampires (Greek: vrykolakas) in his work De Graecorum hodie quorundam opinationibus ("On certain modern opinions among the Greeks").[76] Vampires properly originating in folklore were widely reported from Eastern Europe in the late 17th and 18th centuries. These tales formed the basis of the vampire legend that later entered Germany and England, where they were subsequently embellished and popularized.[77] An early recording of the time came from the region of Istria in modern Croatia, in 1672; Local reports described a panic among the villagers inspired by the belief that Jure Grando had become a vampire after dying in 1656, drinking blood from victims and sexually harassing his widow. The village leader ordered a stake to be driven through his heart. Later, his corpse was also beheaded.[78]

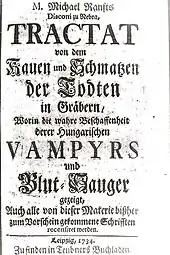

From 1679, Philippe Rohr devotes an essay to the dead who chew their shrouds in their graves, a subject resumed by Otto in 1732, and then by Michael Ranft in 1734. The subject was based on the observation that when digging up graves, it was discovered that some corpses had at some point either devoured the interior fabric of their coffin or their own limbs.[79] Ranft described in his treatise of a tradition in some parts of Germany, that to prevent the dead from masticating they placed a mound of dirt under their chin in the coffin, placed a piece of money and a stone in the mouth, or tied a handkerchief tightly around the throat.[80] In 1732 an anonymous writer writing as "the doctor Weimar" discusses the non-putrefaction of these creatures, from a theological point of view.[81] In 1733, Johann Christoph Harenberg wrote a general treatise on vampirism and the Marquis d'Argens cites local cases. Theologians and clergymen also address the topic.[79]

Some theological disputes arose. The non-decay of vampires' bodies could recall the incorruption of the bodies of the saints of the Catholic Church. A paragraph on vampires was included in the second edition (1749) of De servorum Dei beatificatione et sanctorum canonizatione, On the beatification of the servants of God and on canonization of the blessed, written by Prospero Lambertini (Pope Benedict XIV).[82] In his opinion, while the incorruption of the bodies of saints was the effect of a divine intervention, all the phenomena attributed to vampires were purely natural or the fruit of "imagination, terror and fear". In other words, vampires did not exist.[83]

18th-century vampire controversy

During the 18th century, there was a frenzy of vampire sightings in Eastern Europe, with frequent stakings and grave diggings to identify and kill the potential revenants. Even government officials engaged in the hunting and staking of vampires.[77] Despite being called the Age of Enlightenment, during which most folkloric legends were quelled, the belief in vampires increased dramatically, resulting in a mass hysteria throughout most of Europe.[20] The panic began with an outbreak of alleged vampire attacks in East Prussia in 1721 and in the Habsburg monarchy from 1725 to 1734, which spread to other localities. Two infamous vampire cases, the first to be officially recorded, involved the corpses of Petar Blagojevich and Miloš Čečar from Serbia. Blagojevich was reported to have died at the age of 62, but allegedly returned after his death asking his son for food. When the son refused, he was found dead the following day. Blagojevich supposedly returned and attacked some neighbours who died from loss of blood.[77]

In the second case, Miloš, an ex-soldier-turned-farmer who allegedly was attacked by a vampire years before, died while haying. After his death, people began to die in the surrounding area and it was widely believed that Miloš had returned to prey on the neighbours.[84][85] Another infamous Serbian vampire legend recounts the story of a certain Sava Savanović, who lives in a watermill and kills and drinks blood from the millers. The character was later used in a story written by Serbian writer Milovan Glišić and in the Yugoslav 1973 horror film Leptirica inspired by the story.[86]

The two incidents were well-documented. Government officials examined the bodies, wrote case reports, and published books throughout Europe.[85] The hysteria, commonly referred to as the "18th-Century Vampire Controversy", continued for a generation. The problem was exacerbated by rural epidemics of so-called vampire attacks, undoubtedly caused by the higher amount of superstition that was present in village communities, with locals digging up bodies and in some cases, staking them.[87] Dom Augustine Calmet, a French theologian and scholar, published a comprehensive treatise in 1751 titled Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants which investigated and analysed the evidence for vampirism.[87][lower-alpha 2] Numerous readers, including both a critical Voltaire and numerous supportive demonologists interpreted the treatise as claiming that vampires existed.[87][lower-alpha 3]

The controversy in Austria ceased when Empress Maria Theresa sent her personal physician, Gerard van Swieten, to investigate the claims of vampiric entities. He concluded that vampires did not exist and the Empress passed laws prohibiting the opening of graves and desecration of bodies, ending the vampire epidemics. Other European countries followed suit. Despite this condemnation, the vampire lived on in artistic works and in local folklore.[87]

Non-European beliefs

Beings having many of the attributes of European vampires appear in the folklore of Africa, Asia, North and South America, and India. Classified as vampires, all share the thirst for blood.[90]

Africa

Various regions of Africa have folktales featuring beings with vampiric abilities: in West Africa the Ashanti people tell of the iron-toothed and tree-dwelling asanbosam,[91] and the Ewe people of the adze, which can take the form of a firefly and hunts children.[92] The eastern Cape region has the impundulu, which can take the form of a large taloned bird and can summon thunder and lightning, and the Betsileo people of Madagascar tell of the ramanga, an outlaw or living vampire who drinks the blood and eats the nail clippings of nobles.[93] In colonial East Africa, rumors circulated to the effect that employees of the state such as firemen and nurses were vampires, known in Swahili as wazimamoto.[94]

Americas

The Loogaroo is an example of how a vampire belief can result from a combination of beliefs, here a mixture of French and African Vodu or voodoo. The term Loogaroo possibly comes from the French loup-garou (meaning "werewolf") and is common in the culture of Mauritius. The stories of the Loogaroo are widespread through the Caribbean Islands and Louisiana in the United States.[95] Similar female monsters are the Soucouyant of Trinidad, and the Tunda and Patasola of Colombian folklore, while the Mapuche of southern Chile have the bloodsucking snake known as the Peuchen.[96] Aloe vera hung backwards behind or near a door was thought to ward off vampiric beings in South American folklore.[31] Aztec mythology described tales of the Cihuateteo, skull-faced spirits of those who died in childbirth who stole children and entered into sexual liaisons with the living, driving them mad.[25]

During the late 18th and 19th centuries the belief in vampires was widespread in parts of New England, particularly in Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut. There are many documented cases of families disinterring loved ones and removing their hearts in the belief that the deceased was a vampire who was responsible for sickness and death in the family, although the term "vampire" was never used to describe the dead. The deadly disease tuberculosis, or "consumption" as it was known at the time, was believed to be caused by nightly visitations on the part of a dead family member who had died of consumption themselves.[97] The most famous, and most recently recorded, case of suspected vampirism is that of nineteen-year-old Mercy Brown, who died in Exeter, Rhode Island in 1892. Her father, assisted by the family physician, removed her from her tomb two months after her death, cut out her heart and burned it to ashes.[98]

Asia

Vampires have appeared in Japanese cinema since the late 1950s; the folklore behind it is western in origin.[99] The Nukekubi is a being whose head and neck detach from its body to fly about seeking human prey at night.[100] Legends of female vampiric beings who can detach parts of their upper body also occur in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia. There are two main vampiric creatures in the Philippines: the Tagalog Mandurugo ("blood-sucker") and the Visayan Manananggal ("self-segmenter"). The mandurugo is a variety of the aswang that takes the form of an attractive girl by day, and develops wings and a long, hollow, threadlike tongue by night. The tongue is used to suck up blood from a sleeping victim.[101] The manananggal is described as being an older, beautiful woman capable of severing its upper torso in order to fly into the night with huge batlike wings and prey on unsuspecting, sleeping pregnant women in their homes. They use an elongated proboscis-like tongue to suck fetuses from these pregnant women. They also prefer to eat entrails (specifically the heart and the liver) and the phlegm of sick people.[101]

The Malaysian Penanggalan is a woman who obtained her beauty through the active use of black magic or other unnatural means, and is most commonly described in local folklore to be dark or demonic in nature. She is able to detach her fanged head which flies around in the night looking for blood, typically from pregnant women.[102] Malaysians hung jeruju (thistles) around the doors and windows of houses, hoping the Penanggalan would not enter for fear of catching its intestines on the thorns.[103] The Leyak is a similar being from Balinese folklore of Indonesia.[104] A Kuntilanak or Matianak in Indonesia,[105] or Pontianak or Langsuir in Malaysia,[106] is a woman who died during childbirth and became undead, seeking revenge and terrorising villages. She appeared as an attractive woman with long black hair that covered a hole in the back of her neck, with which she sucked the blood of children. Filling the hole with her hair would drive her off. Corpses had their mouths filled with glass beads, eggs under each armpit, and needles in their palms to prevent them from becoming langsuir. This description would also fit the Sundel Bolongs.[107]

In Vietnam, the word used to translate Western vampires, "ma cà rồng", originally referred to a type of demon that haunts modern-day Phú Thọ Province, within the communities of the Tai Dam ethnic minority. The word was first mentioned in the chronicles of 18th-century Confucian scholar Lê Quý Đôn,[108] who spoke of a creature that lives among humans, but stuffs its toes into its nostrils at night and flies by its ears into houses with pregnant women to suck their blood. Having fed on these women, the ma cà rồng then returns to its house and cleans itself by dipping its toes into barrels of sappanwood water. This allows the ma cà rồng to live undetected among humans during the day, before heading out to attack again by night.[109]

Jiangshi, sometimes called "Chinese vampires" by Westerners, are reanimated corpses that hop around, killing living creatures to absorb life essence (qì) from their victims. They are said to be created when a person's soul (魄 pò) fails to leave the deceased's body.[110] Jiangshi are usually represented as mindless creatures with no independent thought.[111] This monster has greenish-white furry skin, perhaps derived from fungus or mould growing on corpses.[112] Jiangshi legends have inspired a genre of jiangshi films and literature in Hong Kong and East Asia. Films like Encounters of the Spooky Kind and Mr. Vampire were released during the jiangshi cinematic boom of the 1980s and 1990s.[113][114]

Modern beliefs

In modern fiction, the vampire tends to be depicted as a suave, charismatic villain.[22] Vampire hunting societies still exist, but they are largely formed for social reasons.[20] Allegations of vampire attacks swept through Malawi during late 2002 and early 2003, with mobs stoning one person to death and attacking at least four others, including Governor Eric Chiwaya, based on the belief that the government was colluding with vampires.[115] Fears and violence recurred in late 2017, with 6 people accused of being vampires killed.[116]

In early 1970, local press spread rumours that a vampire haunted Highgate Cemetery in London. Amateur vampire hunters flocked in large numbers to the cemetery. Several books have been written about the case, notably by Sean Manchester, a local man who was among the first to suggest the existence of the "Highgate Vampire" and who later claimed to have exorcised and destroyed a whole nest of vampires in the area.[117] In January 2005, rumours circulated that an attacker had bitten a number of people in Birmingham, England, fuelling concerns about a vampire roaming the streets. Local police stated that no such crime had been reported and that the case appears to be an urban legend.[118]

The chupacabra ("goat-sucker") of Puerto Rico and Mexico is said to be a creature that feeds upon the flesh or drinks the blood of domesticated animals, leading some to consider it a kind of vampire. The "chupacabra hysteria" was frequently associated with deep economic and political crises, particularly during the mid-1990s.[119]

In Europe, where much of the vampire folklore originates, the vampire is usually considered a fictitious being; many communities may have embraced the revenant for economic purposes. In some cases, especially in small localities, beliefs are still rampant and sightings or claims of vampire attacks occur frequently. In Romania during February 2004, several relatives of Toma Petre feared that he had become a vampire. They dug up his corpse, tore out his heart, burned it, and mixed the ashes with water in order to drink it.[120]

Origins of vampire beliefs

Commentators have offered many theories for the origins of vampire beliefs and related mass hysteria. Everything ranging from premature burial to the early ignorance of the body's decomposition cycle after death has been cited as the cause for the belief in vampires.[121]

Decomposition

Author Paul Barber stated that belief in vampires resulted from people of pre-industrial societies attempting to explain the natural, but to them inexplicable, process of death and decomposition.[121] People sometimes suspected vampirism when a cadaver did not look as they thought a normal corpse should when disinterred. Rates of decomposition vary depending on temperature and soil composition, and many of the signs are little known. This has led vampire hunters to mistakenly conclude that a dead body had not decomposed at all or to interpret signs of decomposition as signs of continued life.[122]

Corpses swell as gases from decomposition accumulate in the torso and the increased pressure forces blood to ooze from the nose and mouth. This causes the body to look "plump", "well-fed", and "ruddy"—changes that are all the more striking if the person was pale or thin in life. In the Arnold Paole case, an old woman's exhumed corpse was judged by her neighbours to look more plump and healthy than she had ever looked in life.[123] The exuding blood gave the impression that the corpse had recently been engaging in vampiric activity.[35] Darkening of the skin is also caused by decomposition.[124] The staking of a swollen, decomposing body could cause the body to bleed and force the accumulated gases to escape the body. This could produce a groan-like sound when the gases moved past the vocal cords, or a sound reminiscent of flatulence when they passed through the anus. The official reporting on the Petar Blagojevich case speaks of "other wild signs which I pass by out of high respect".[125] After death, the skin and gums lose fluids and contract, exposing the roots of the hair, nails, and teeth, even teeth that were concealed in the jaw. This can produce the illusion that the hair, nails, and teeth have grown. At a certain stage, the nails fall off and the skin peels away, as reported in the Blagojevich case—the dermis and nail beds emerging underneath were interpreted as "new skin" and "new nails".[125]

Premature burial

Vampire legends may have also been influenced by individuals being buried alive because of shortcomings in the medical knowledge of the time. In some cases in which people reported sounds emanating from a specific coffin, it was later dug up and fingernail marks were discovered on the inside from the victim trying to escape. In other cases the person would hit their heads, noses or faces and it would appear that they had been "feeding".[126] A problem with this theory is the question of how people presumably buried alive managed to stay alive for any extended period without food, water or fresh air. An alternate explanation for noise is the bubbling of escaping gases from natural decomposition of bodies.[127] Another likely cause of disordered tombs is grave robbery.[128]

Disease

Folkloric vampirism has been associated with clusters of deaths from unidentifiable or mysterious illnesses, usually within the same family or the same small community.[97] The epidemic allusion is obvious in the classical cases of Petar Blagojevich and Arnold Paole, and even more so in the case of Mercy Brown and in the vampire beliefs of New England generally, where a specific disease, tuberculosis, was associated with outbreaks of vampirism. As with the pneumonic form of bubonic plague, it was associated with breakdown of lung tissue which would cause blood to appear at the lips.[129]

In 1985, biochemist David Dolphin proposed a link between the rare blood disorder porphyria and vampire folklore. Noting that the condition is treated by intravenous haem, he suggested that the consumption of large amounts of blood may result in haem being transported somehow across the stomach wall and into the bloodstream. Thus vampires were merely sufferers of porphyria seeking to replace haem and alleviate their symptoms.[130]

The theory has been rebuffed medically as suggestions that porphyria sufferers crave the haem in human blood, or that the consumption of blood might ease the symptoms of porphyria, are based on a misunderstanding of the disease. Furthermore, Dolphin was noted to have confused fictional (bloodsucking) vampires with those of folklore, many of whom were not noted to drink blood.[131] Similarly, a parallel is made between sensitivity to sunlight by sufferers, yet this was associated with fictional and not folkloric vampires. In any case, Dolphin did not go on to publish his work more widely.[132] Despite being dismissed by experts, the link gained media attention[133] and entered popular modern folklore.[134]

Juan Gómez-Alonso, a neurologist, examined the possible link of rabies with vampire folklore. The susceptibility to garlic and light could be due to hypersensitivity, which is a symptom of rabies. It can also affect portions of the brain that could lead to disturbance of normal sleep patterns (thus becoming nocturnal) and hypersexuality. Legend once said a man was not rabid if he could look at his own reflection (an allusion to the legend that vampires have no reflection). Wolves and bats, which are often associated with vampires, can be carriers of rabies. The disease can also lead to a drive to bite others and to a bloody frothing at the mouth.[135][136]

Psychodynamic theories

In his 1931 treatise On the Nightmare, Welsh psychoanalyst Ernest Jones asserted that vampires are symbolic of several unconscious drives and defence mechanisms. Emotions such as love, guilt, and hate fuel the idea of the return of the dead to the grave. Desiring a reunion with loved ones, mourners may project the idea that the recently dead must in return yearn the same. From this arises the belief that folkloric vampires and revenants visit relatives, particularly their spouses, first.[137]

In cases where there was unconscious guilt associated with the relationship, the wish for reunion may be subverted by anxiety. This may lead to repression, which Sigmund Freud had linked with the development of morbid dread.[138] Jones surmised in this case the original wish of a (sexual) reunion may be drastically changed: desire is replaced by fear; love is replaced by sadism, and the object or loved one is replaced by an unknown entity. The sexual aspect may or may not be present.[139] Some modern critics have proposed a simpler theory: People identify with immortal vampires because, by so doing, they overcome, or at least temporarily escape from, their fear of dying.[140]

Jones linked the innate sexuality of bloodsucking with cannibalism, with a folkloric connection with incubus-like behaviour. He added that when more normal aspects of sexuality are repressed, regressed forms may be expressed, in particular sadism; he felt that oral sadism is integral in vampiric behaviour.[141]

Political interpretations

%252C_199_-_BL.jpg.webp)

The reinvention of the vampire myth in the modern era is not without political overtones.[142] The aristocratic Count Dracula, alone in his castle apart from a few demented retainers, appearing only at night to feed on his peasantry, is symbolic of the parasitic ancien régime. In his entry for "Vampires" in the Dictionnaire philosophique (1764), Voltaire notices how the mid-18th century coincided with the decline of the folkloric belief in the existence of vampires but that now "there were stock-jobbers, brokers, and men of business, who sucked the blood of the people in broad daylight; but they were not dead, though corrupted. These true suckers lived not in cemeteries, but in very agreeable palaces".[143]

Marx defined capital as "dead labour which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks".[lower-alpha 4] Werner Herzog, in his Nosferatu the Vampyre, gives this political interpretation an extra ironic twist when protagonist Jonathan Harker, a middle-class solicitor, becomes the next vampire; in this way the capitalist bourgeois becomes the next parasitic class.[144]

Psychopathology

A number of murderers have performed seemingly vampiric rituals upon their victims. Serial killers Peter Kürten and Richard Trenton Chase were both called "vampires" in the tabloids after they were discovered drinking the blood of the people they murdered. In 1932, an unsolved murder case in Stockholm, Sweden, was nicknamed the "Vampire murder", because of the circumstances of the victim's death.[145] The late-16th-century Hungarian countess and mass murderer Elizabeth Báthory became infamous in later centuries' works, which depicted her bathing in her victims' blood to retain beauty or youth.[146]

Vampire bats

Although many cultures have stories about them, vampire bats have only recently become an integral part of the traditional vampire lore. Vampire bats were integrated into vampire folklore after they were discovered on the South American mainland in the 16th century.[147] There are no vampire bats in Europe, but bats and owls have long been associated with the supernatural and omens, mainly because of their nocturnal habits.[147][148]

The three species of vampire bats are all endemic to Latin America, and there is no evidence to suggest that they had any Old World relatives within human memory. It is therefore impossible that the folkloric vampire represents a distorted presentation or memory of the vampire bat. The bats were named after the folkloric vampire rather than vice versa; the Oxford English Dictionary records their folkloric use in English from 1734 and the zoological not until 1774. The danger of rabies infection aside, the vampire bat's bite is usually not harmful to a person, but the bat has been known to actively feed on humans and large prey such as cattle and often leaves the trademark, two-prong bite mark on its victim's skin.[147]

The literary Dracula transforms into a bat several times in the novel, and vampire bats themselves are mentioned twice in it. The 1927 stage production of Dracula followed the novel in having Dracula turn into a bat, as did the film, where Béla Lugosi would transform into a bat.[147] The bat transformation scene was used again by Lon Chaney Jr. in 1943's Son of Dracula.[149]

In modern culture

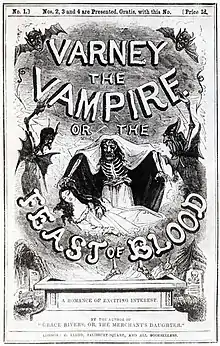

The vampire is now a fixture in popular fiction. Such fiction began with 18th-century poetry and continued with 19th-century short stories, the first and most influential of which was John Polidori's "The Vampyre" (1819), featuring the vampire Lord Ruthven.[150] Lord Ruthven's exploits were further explored in a series of vampire plays in which he was the antihero. The vampire theme continued in penny dreadful serial publications such as Varney the Vampire (1847) and culminated in the pre-eminent vampire novel in history: Dracula by Bram Stoker, published in 1897.[151]

Over time, some attributes now regarded as integral became incorporated into the vampire's profile: fangs and vulnerability to sunlight appeared over the course of the 19th century, with Varney the Vampire and Count Dracula both bearing protruding teeth,[152] and Count Orlok of Murnau's Nosferatu (1922) fearing daylight.[153] The cloak appeared in stage productions of the 1920s, with a high collar introduced by playwright Hamilton Deane to help Dracula 'vanish' on stage.[154] Lord Ruthven and Varney were able to be healed by moonlight, although no account of this is known in traditional folklore.[155] Implied though not often explicitly documented in folklore, immortality is one attribute which features heavily in vampire films and literature. Much is made of the price of eternal life, namely the incessant need for the blood of former equals.[156]

Literature

The vampire or revenant first appeared in poems such as The Vampire (1748) by Heinrich August Ossenfelder, Lenore (1773) by Gottfried August Bürger, Die Braut von Corinth (The Bride of Corinth) (1797) by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Robert Southey's Thalaba the Destroyer (1801), John Stagg's "The Vampyre" (1810), Percy Bysshe Shelley's "The Spectral Horseman" (1810) ("Nor a yelling vampire reeking with gore") and "Ballad" in St. Irvyne (1811) about a reanimated corpse, Sister Rosa, Samuel Taylor Coleridge's unfinished Christabel and Lord Byron's The Giaour.[157]

Byron was also credited with the first prose fiction piece concerned with vampires: "The Vampyre" (1819). This was in reality authored by Byron's personal physician, John Polidori, who adapted an enigmatic fragmentary tale of his illustrious patient, "Fragment of a Novel" (1819), also known as "The Burial: A Fragment".[20][151] Byron's own dominating personality, mediated by his lover Lady Caroline Lamb in her unflattering roman-a-clef Glenarvon (a Gothic fantasia based on Byron's wild life), was used as a model for Polidori's undead protagonist Lord Ruthven. The Vampyre was highly successful and the most influential vampire work of the early 19th century.[158]

Varney the Vampire was a popular mid-Victorian era gothic horror story by James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest, which first appeared from 1845 to 1847 in a series of pamphlets generally referred to as penny dreadfuls because of their low price and gruesome contents.[150] Published in book form in 1847, the story runs to 868 double-columned pages. It has a distinctly suspenseful style, using vivid imagery to describe the horrifying exploits of Varney.[155] Another important addition to the genre was Sheridan Le Fanu's lesbian vampire story Carmilla (1871). Like Varney before her, the vampiress Carmilla is portrayed in a somewhat sympathetic light as the compulsion of her condition is highlighted.[159]

No effort to depict vampires in popular fiction was as influential or as definitive as Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897).[160] Its portrayal of vampirism as a disease of contagious demonic possession, with its undertones of sex, blood and death, struck a chord in Victorian Europe where tuberculosis and syphilis were common. The vampiric traits described in Stoker's work merged with and dominated folkloric tradition, eventually evolving into the modern fictional vampire.[150]

Drawing on past works such as The Vampyre and Carmilla, Stoker began to research his new book in the late 19th century, reading works such as The Land Beyond the Forest (1888) by Emily Gerard and other books about Transylvania and vampires. In London, a colleague mentioned to him the story of Vlad Ţepeş, the "real-life Dracula", and Stoker immediately incorporated this story into his book. The first chapter of the book was omitted when it was published in 1897, but it was released in 1914 as "Dracula's Guest".[161]

The latter part of the 20th century saw the rise of multi-volume vampire epics as well as a renewed interest in the subject in books. The first of these was Gothic romance writer Marilyn Ross's Barnabas Collins series (1966–71), loosely based on the contemporary American TV series Dark Shadows. It also set the trend for seeing vampires as poetic tragic heroes rather than as the more traditional embodiment of evil. This formula was followed in novelist Anne Rice's highly popular Vampire Chronicles (1976–2003),[162] and Stephenie Meyer's Twilight series (2005–2008).[163]

Film and television

Considered one of the preeminent figures of the classic horror film, the vampire has proven to be a rich subject for the film, television, and gaming industries. Dracula is a major character in more films than any other but Sherlock Holmes, and many early films were either based on the novel Dracula or closely derived from it. These included the 1922 silent German Expressionist horror film Nosferatu, directed by F. W. Murnau and featuring the first film portrayal of Dracula—although names and characters were intended to mimic Dracula's.[164] Universal's Dracula (1931), starring Béla Lugosi as the Count and directed by Tod Browning, was the first talking film to portray Dracula. Both Lugosi's performance and the film overall were influential in the blossoming horror film genre, now able to use sound and special effects much more efficiently than in the Silent Film Era. The influence of this 1931 film lasted throughout the rest of the 20th century and up through the present day. Stephen King, Francis Ford Coppola, Hammer Horror, and Philip Saville each have at one time or another derived inspiration from this film directly either through staging or even through directly quoting the film, particularly how Stoker's line "Listen to them. Children of the night. What music they make!" is delivered by Lugosi; for example Coppola paid homage to this moment with Gary Oldman in his interpretation of the tale in 1992 and King has credited this film as an inspiration for his character Kurt Barlow repeatedly in interviews.[165] It is for these reasons that the film was selected by the US Library of Congress to be in the National Film Registry in 2000.[166]

The legend of the vampire continued through the film industry when Dracula was reincarnated in the pertinent Hammer Horror series of films, starring Christopher Lee as the Count. The successful 1958 Dracula starring Lee was followed by seven sequels. Lee returned as Dracula in all but two of these and became well known in the role.[167] By the 1970s, vampires in films had diversified with works such as Count Yorga, Vampire (1970), an African Count in 1972's Blacula, the BBC's Count Dracula featuring French actor Louis Jourdan as Dracula and Frank Finlay as Abraham Van Helsing, and a Nosferatu-like vampire in 1979's Salem's Lot, and a remake of Nosferatu itself, titled Nosferatu the Vampyre with Klaus Kinski the same year. Several films featured the characterization of a female, often lesbian, vampire such as Hammer Horror's The Vampire Lovers (1970), based on Carmilla, though the plotlines still revolved around a central evil vampire character.[167]

The Gothic soap opera Dark Shadows, on American television from 1966 to 1971, featured the vampire character Barnabas Collins, portrayed by Jonathan Frid, which proved partly responsible for making the series one of the most popular of its type, amassing a total of 1,225 episodes in its nearly five-year run. The pilot for the later 1972 television series Kolchak: The Night Stalker revolved around a reporter hunting a vampire on the Las Vegas Strip. Later films showed more diversity in plotline, with some focusing on the vampire-hunter, such as Blade in the Marvel Comics' Blade films and the film Buffy the Vampire Slayer.[150] Buffy, released in 1992, foreshadowed a vampiric presence on television, with its adaptation to a series of the same name and its spin-off Angel. Others showed the vampire as a protagonist, such as 1983's The Hunger, 1994's Interview with the Vampire and its indirect sequel Queen of the Damned, and the 2007 series Moonlight. The 1992 film Bram Stoker's Dracula by Francis Ford Coppola became the then-highest grossing vampire film ever.[168]

This increase of interest in vampiric plotlines led to the vampire being depicted in films such as Underworld and Van Helsing, the Russian Night Watch and a TV miniseries remake of Salem's Lot, both from 2004. The series Blood Ties premiered on Lifetime Television in 2007, featuring a character portrayed as Henry Fitzroy, an illegitimate-son-of-Henry-VIII-of-England-turned-vampire, in modern-day Toronto, with a female former Toronto detective in the starring role. A 2008 series from HBO, entitled True Blood, gives a Southern Gothic take on the vampire theme.[163] In 2008 Being Human premiered in Britain and featured a vampire that shared a flat with a werewolf and a ghost.[169][170] The continuing popularity of the vampire theme has been ascribed to a combination of two factors: the representation of sexuality and the perennial dread of mortality.[171]

Games

The role-playing game Vampire: The Masquerade has been influential upon modern vampire fiction and elements of its terminology, such as embrace and sire, appear in contemporary fiction.[150] Popular video games about vampires include Castlevania, which is an extension of the original Bram Stoker novel Dracula, and Legacy of Kain.[172] The role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons features vampires.[173]

Modern vampire subcultures

Vampire lifestyle is a term for a contemporary subculture of people, largely within the Goth subculture, who consume the blood of others as a pastime; drawing from the rich recent history of popular culture related to cult symbolism, horror films, the fiction of Anne Rice, and the styles of Victorian England.[174] Active vampirism within the vampire subculture includes both blood-related vampirism, commonly referred to as sanguine vampirism, and psychic vampirism, or supposed feeding from pranic energy.[175][176]

Notes

- Vampires had already been discussed in French[16] and German literature.[17]

- Calmet conducted extensive research and amassed judicial reports of vampiric incidents and extensively researched theological and mythological accounts as well, using the scientific method in his analysis to come up with methods for determining the validity for cases of this nature. As he stated in his treatise:[88]

They see, it is said, men who have been dead for several months, come back to earth, talk, walk, infest villages, ill use both men and beasts, suck the blood of their near relations, make them ill, and finally cause their death; so that people can only save themselves from their dangerous visits and their hauntings by exhuming them, impaling them, cutting off their heads, tearing out the heart, or burning them. These revenants are called by the name of oupires or vampires, that is to say, leeches; and such particulars are related of them, so singular, so detailed, and invested with such probable circumstances and such judicial information, that one can hardly refuse to credit the belief which is held in those countries, that these revenants come out of their tombs and produce those effects which are proclaimed of them.

- In the Philosophical Dictionary, Voltaire wrote:[89]

These vampires were corpses, who went out of their graves at night to suck the blood of the living, either at their throats or stomachs, after which they returned to their cemeteries. The persons so sucked waned, grew pale, and fell into consumption; while the sucking corpses grew fat, got rosy, and enjoyed an excellent appetite. It was in Poland, Hungary, Silesia, Moravia, Austria, and Lorraine, that the dead made this good cheer.

- An extensive discussion of the different uses of the vampire metaphor in Marx's writings can be found in Policante, A. (2010). "Vampires of Capital: Gothic Reflections between horror and hope" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2012. in Cultural Logic Archived 6 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 2010.

References

- Lane, Nick (16 December 2002). "Born to the Purple: the Story of Porphyria". Scientific American. New York City: Springer Nature. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Katharina M. Wilson (1985). The History of the Word "Vampire" Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 46. p. 583

- "Deutsches Wörterbuch von Jacob Grimm und Wilhelm Grimm. 16 Bde. (in 32 Teilbänden). Leipzig: S. Hirzel 1854–1960" (in German). Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2006.

- "Vampire". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 13 June 2006.

- "Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé" (in French). Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2006.

- Tokarev, Sergei Aleksandrovich (1982). Mify Narodov Mira (in Russian). Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya: Moscow. OCLC 7576647. ("Myths of the Peoples of the World"). Upyr'

- "Russian Etymological Dictionary by Max Vasmer" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 4 May 2006. Retrieved 13 June 2006.

- Husić, Geoff. "A Vampire by Any Other Name".

- Yaltırık, Mehmet Berk; Sarpkaya, Seçkin (2018). Turkish: Türk Kültüründe Vampirler, English translation: Vampires in Turkic Culture (in Turkish). Karakum Yayınevi. pp. 43–49.

- (in Bulgarian)Mladenov, Stefan (1941). Etimologičeski i pravopisen rečnik na bǎlgarskiya knižoven ezik.

- MACHEK, V.: Etymologický slovník jazyka českého, 5th edition, NLN, Praha 2010

- Wilson, Katharina M. (1985). "The History of the Word "Vampire"". Journal of the History of Ideas. 46 (4): 577–583. doi:10.2307/2709546. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2709546.

- Рыбаков Б.А. Язычество древних славян / М.: Издательство 'Наука,' 1981 г. (in Russian). Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- Зубов, Н.И. (1998). Загадка Периодизации Славянского Язычества В Древнерусских Списках "Слова Св. Григория ... О Том, Како Первое Погани Суще Языци, Кланялися Идолом ...". Живая Старина (in Russian). 1 (17): 6–10. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- Mutch, Deborah, ed. (2013). The Modern Vampire and Human Identity. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-349-35069-8.

- Vermeir, Keir (January 2012). "Vampires as Creatures of the Imagination: Theories of Body, Soul, and Imagination in Early Modern Vampire Tracts (1659–1755)". In Haskell, Y (ed.). Diseases of the Imagination and Imaginary Disease in the Early Modern Period. Tunhout, Belgium: Brepols Publishers. ISBN 978-2-503-52796-3.

- Barber, p. 5.

- Dauzat, Albert (1938). Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue française (in French). Paris, France: Librairie Larousse. OCLC 904687.

- Silver, Alain; Ursini, James (1997). The Vampire Film: From Nosferatu to Interview with the Vampire. New York City: Limelight Editions. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-87910-395-8.

- Cohen 1989, pp. 271–274.

- Barber 1988, pp. 41–42.

- Barber 1988, p. 2.

- Calmet, Augustin (2018) [1751]. The Phantom World. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-7340-3275-2.

- Barber 1988, p. 33.

- Reader's Digest Association (1988). "Vampires Galore!". The Reader's Digest Book of strange stories, amazing facts: stories that are bizarre, unusual, odd, astonishing, incredible ... but true. New York City: Reader's Digest. pp. 432–433. ISBN 978-0-949819-89-5.

- Albanologjike, Gjurmime (1985). Folklor dhe etnologji (in Albanian). Vol. 15. pp. 58–148. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- Barber 1988, pp. 50–51.

- Lawson, John Cuthbert (1910). Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 405–06. ISBN 978-0-524-02024-1. OCLC 1465746.

- Barber 1988, p. 49.

- Abbott, George (1903). Macedonian Folklore. Cambridge, University press. p. 219.

- Jaramillo Londoño, Agustín (1986) [1967]. Testamento del paisa (in Spanish) (7th ed.). Medellín: Susaeta Ediciones. ISBN 978-958-95125-0-0.

- Barber 1988, pp. 68–69.

- Barber 1988, p. 125.

- Barber 1988, p. 109.

- Barber 1988, pp. 114–115.

- Barber 1988, p. 96.

- Bunson 1993, pp. 168–169.

- Barber 1988, p. 6.

- Burkhardt, Dagmar (1966). "Vampirglaube und Vampirsage auf dem Balkan". Beiträge zur Südosteuropa-Forschung: Anlässlich des I. Internationalen Balkanologenkongresses in Sofia 26. VIII.-1. IX. 1966 (in German). Munich: Rudolf Trofenik. p. 221. OCLC 1475919.

- Barber 1988, p. 63.

- Mappin, Jenni (2003). Didjaknow: Truly Amazing & Crazy Facts About ... Everything. Australia: Pancake. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-330-40171-5.

- Spence, Lewis (1960). An Encyclopaedia of Occultism. New Hyde Parks: University Books. ISBN 978-0-486-42613-6. OCLC 3417655.

- Silver & Ursini 1997, p. 25.

- Calmet, Augustin (1850). The Phantom World: The History and Philosophy of Spirits, Apparitions, &c., &c. A. Hart. p. 273.

- Calmet, Augustin (1850). The Phantom World: The History and Philosophy of Spirits, Apparitions, &c., &c. A. Hart. p. 265.

- Mitchell, Stephen A. (2011). Witchcraft and Magic in the Nordic Middle Ages. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-8122-4290-4. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- Barber 1988, p. 73.

- Alseikaite-Gimbutiene, Marija (1946). Die Bestattung in Litauen in der vorgeschichtlichen Zeit (in German). Tübingen. OCLC 1059867.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (thesis). - Vukanović, T.P. (1959). "The Vampire". Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society. 38: 111–18.

- Klapper, Joseph (1909). "Die schlesischen Geschichten von den schädingenden Toten". Mitteilungen der Schlesischen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde (in German). 11: 58–93.

- Calmet, Augustin (30 December 2015). Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

- Theresa Cheung (2013). The Element Encyclopedia of Vampires. HarperCollins UK. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-00-752473-0.

- Löwenstimm, A. (1897). Aberglaube und Stafrecht (in German). Berlin. p. 99.

- Bachtold-Staubli, H. (1934–1935). Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens (in German). Berlin.

- Filipovic, Milenko (1962). "Die Leichenverbrennung bei den Südslaven". Wiener Völkerkundliche Mitteilungen (in German). 10: 61–71.

- Barber 1988, p. 158.

- Barber 1988, p. 157.

- "'Vampire' skeletons found in Bulgaria near Black Sea". BBC News. 6 June 2012. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Reported by Ariel David, "Italy dig unearths female 'vampire' in Venice", 13 March 2009, Associated Press via Yahoo! News, archived; also by Reuters, published under the headline "Researchers find remains that support medieval 'vampire'" in The Australian, 13 March 2009, archived with photo (scroll down).

- Bunson 1993, p. 154.

- McNally, Raymond T.; Florescu, Radu (1994). In Search of Dracula. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-395-65783-6.

- Marigny 1994, pp. 24–25.

- Burton, Sir Richard R. (1893) [1870]. Vikram and The Vampire: Classic Hindu Tales of Adventure, Magic, and Romance. London: Tylston and Edwards. ISBN 978-0-89281-475-6. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- Bunson 1993, p. 200.

- Marigny 1994, p. 14.

- Hurwitz, Siegmund (1992) [1980]. Lilith, the First Eve: Historical and Psychological Aspects of the Dark Feminine. Gela Jacobson (trans.). Einsiedeln, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag. pp. 39–51. ISBN 978-3-85630-522-2.

- Shael, Rabbi (1 June 2009). "Rabbi Shael Speaks ... Tachles: Vampires, Einstein and Jewish Folklore". Shaelsiegel.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- Graves 1990, pp. 189–190.

- Graves 1990, pp. 205–206.

- "Philostr Vit. Apoll. iv. 25; Suid. s. v." Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- Oliphant, Samuel Grant (1913). "The Story of the Strix: Ancient". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 44: 133–49. doi:10.2307/282549. ISSN 0065-9711. JSTOR 282549.

- William of Newburgh; Paul Halsall (2000). "Book 5, Chapter 22–24". Historia rerum Anglicarum. Fordham University. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- Jones 1931, p. 121.

- Jakobsson, Ármann (2009). "The Fearless Vampire Killers: A Note about the Icelandic Draugr and Demonic Contamination in Grettis Saga". Folklore (120): 309.

- Epstein, Saul; Robinson, Sara Libby (2012). "The Soul, Evil Spirits, and the Undead: Vampires, Death, and Burial in Jewish Folklore and Law". Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural. 1 (2): 232–51. doi:10.5325/preternature.1.2.0232.

- Melton, J. Gordon (2010). The Vampire Book: The encyclopedia of the Undead. Visible Ink Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-1-57859-350-7.

- Barber 1988, pp. 5–9.

- Bohn, Thomas M. (2019). The Vampire: Origins of a European Myth. Cologne: Berghahn Books. pp. 47–49. ISBN 978-1-78920-293-9.

- Marigny, Jean (1993). Sang pour Sang, Le Réveil des Vampires, Gallimard, coll. Gallimard. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-2-07-053203-2.

- Calmet, Augustin (1751). Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2015. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 442–443. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

- Lecouteux, Claude (1993). Historie des vampires: Autopsie d'un mythe. Paris: Imago. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-2-911416-29-3.

- Lambertini, P. (1749). "XXXI". De servorum Dei beatificatione et sanctorum canonizatione. Vol. Pars prima. pp. 323–24.

- de Ceglia F.P. (2011). "The Archbishop's Vampires. Giuseppe Davanzati's Dissertation and the Reaction of Scientific Italian Catholicism to the Moravian Events". Archives Internationales d'Histoire des Sciences. 61 (166/167): 487–510. doi:10.1484/J.ARIHS.5.101493.

- Jøn, A. Asbjørn (2003). "Vampire Evolution". METAphor (3): 20. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Barber 1988, pp. 15–21.

- Ruthven, Suzanne (2014). Charnel House Blues: The Vampyre's Tale. John Hunt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78279-415-8. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- Hoyt 1984, p. 101-106.

- Calmet, Augustin (1751). Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. Translated by Rev Henry Christmas & Brett Warren. 2015. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 303–304. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

- Voltaire (1984) [1764]. Philosophical Dictionary. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-044257-1.

- Atwater, Cheryl (2000). "Living in Death: The Evolution of Modern Vampirism". Anthropology of Consciousness. 11 (1–2): 70–77. doi:10.1525/ac.2000.11.1-2.70.

- Bunson 1993, p. 11.

- Bunson 1993, p. 2.

- Bunson 1993, p. 219.

- White, Luise (31 December 2000). Speaking with Vampires. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520922297. ISBN 978-0-520-92229-7. S2CID 258526552. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- Bunson 1993, pp. 162–163.

- Martinez Vilches, Oscar (1992). Chiloe Misterioso: Turismo, Mitologia Chilota, leyendas (in Spanish). Chile: Ediciones de la Voz de Chiloe. p. 179. OCLC 33852127.

- Sledzik, Paul S.; Nicholas Bellantoni (1994). "Bioarcheological and biocultural evidence for the New England vampire folk belief". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 94 (2): 269–274. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330940210. PMID 8085617.

- Bell, Michael E. (2006). "Vampires and Death in New England, 1784 to 1892". Anthropology and Humanism. 31 (2): 124–40. doi:10.1525/ahu.2006.31.2.124.

- Bunson 1993, pp. 137–138.

- Hearn, Lafcadio (1903). Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. ISBN 978-0-585-15043-7.

- Ramos, Maximo D. (1990) [1971]. Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology. Quezon: Phoenix Publishing. ISBN 978-971-06-0691-7.

- Bunson 1993, p. 197.

- Hoyt 1984, p. 34.

- Stephen, Michele (1999). "Witchcraft, Grief, and the Ambivalence of Emotions". American Ethnologist. 26 (3): 711–737. doi:10.1525/ae.1999.26.3.711.

- Bunson 1993, p. 208.

- Bunson 1993, p. 150.

- Hoyt 1984, p. 35.

- Lê Quý Đôn (2007). Kiến văn tiểu lục. NXB Văn hóa-Thông tin. p. 353.

- Trương Quốc Dụng (2020). Thoái thực ký văn. Writers' Association Publishing House.

- Suckling, Nigel (2006). Vampires. London: Facts, Figures & Fun. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-904332-48-0.

- 劉, 天賜 (2008). 僵屍與吸血鬼. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing (H.K.). p. 196. ISBN 978-962-04-2735-0.

- de Groot, J.J.M. (1910). The Religious System of China. OCLC 7022203.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Lam, Stephanie (2009). "Hop on Pop: Jiangshi Films in a Transnational Context". CineAction (78): 46–51.

- Hudson, Dave (2009). Draculas, Vampires, and Other Undead Forms. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-8108-6923-3.

- Tenthani, Raphael (23 December 2002). "'Vampires' strike Malawi villages". BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- "Mobs in Malawi have killed six people for being "vampires"". VICE News. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- Manchester, Sean (1991). The Highgate Vampire: The Infernal World of the Undead Unearthed at London's Highgate Cemetery and Environs. London: Gothic Press. ISBN 978-1-872486-01-7.

- Jeffries, Stuart (18 January 2005). "Reality Bites". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- Stephen Wagner. "On the trail of the Chupacabras". Archived from the original on 19 September 2005. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- Taylor, T. (28 October 2007). "The real vampire slayers". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- Barber 1988, pp. 1–4.

- Barber, Paul (March–April 1996). "Staking Claims: The Vampires of Folklore and Fiction". Skeptical Inquirer. 20 (2). Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Barber 1988, p. 117.

- Barber 1988, p. 105.

- Barber 1988, p. 119.

- Marigny 1994, pp. 48–49.

- Barber 1988, p. 128.

- Barber 1988, pp. 137–138.

- Barber 1988, p. 115.

- Cox, Ann M. (1995). "Porphyria and vampirism: another myth in the making". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 71 (841): 643–644. doi:10.1136/pgmj.71.841.643-a. PMC 2398345. PMID 7494765. S2CID 29495879.

- Barber 1988, p. 100.

- Adams, Cecil (7 May 1999). "Did vampires suffer from the disease porphyria—or not?". The Straight Dope. Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 25 December 2007.

- Pierach, Claus A. (13 June 1985). "Vampire Label Unfair To Porphyria Sufferers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 25 December 2007.

- Kujtan, Peter W. (29 October 2005). "Porphyria: The Vampire Disease". The Mississauga News online. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- Gómez-Alonso, Juan (1998). "Rabies: a possible explanation for the vampire legend". Neurology. 51 (3): 856–59. doi:10.1212/WNL.51.3.856. PMID 9748039. S2CID 219202098.

- "Rabies-The Vampire's Kiss". BBC News. 24 September 1998. Archived from the original on 17 March 2006. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- Jones 1931, pp. 100–102.

- Jones, Ernest (1911). "The Pathology of Morbid Anxiety". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 6 (2): 81–106. doi:10.1037/h0074306. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- Jones 1931, p. 106.

- McMahon, Twilight of an Idol, p. 193 Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Jones 1931, pp. 116–120.

- Glover, David (1996). Vampires, Mummies, and Liberals: Bram Stoker and the Politics of Popular Fiction. Durham, NC.: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1798-2.

- "Vampires. – Voltaire, The Works of Voltaire, Vol. VII (Philosophical Dictionary Part 5) (1764)". Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Brass, Tom (2000). "Nymphs, Shepherds, and Vampires: The Agrarian Myth on Film". Dialectical Anthropology. 25 (3/4): 205–237. doi:10.1023/A:1011615201664. S2CID 141136948.

- Linnell, Stig (1993) [1968]. Stockholms spökhus och andra ruskiga ställen (in Swedish). Raben Prisma. ISBN 978-91-518-2738-4.

- Hoyt 1984, pp. 68–71.

- Cohen 1989, pp. 95–96.

- Cooper, J.C. (1992). Symbolic and Mythological Animals. London: Aquarian Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1-85538-118-6.

- Skal 1996, pp. 19–21.

- Jøn, A. Asbjørn (2001). "From Nosteratu to Von Carstein: shifts in the portrayal of vampires". Australian Folklore: A Yearly Journal of Folklore Studies (16): 97–106. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Frayling, Christopher (1991). Vampyres, Lord Byron to Count Dracula. London: Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-16792-0.

- Skal 1996, p. 99.

- Skal 1996, p. 104.

- Skal 1996, p. 62.

- Silver & Ursini 1997, pp. 38–39.

- Bunson 1993, p. 131.

- Marigny 1994, pp. 114–115.

- Silver & Ursini 1997, pp. 37–38.

- Silver & Ursini 1997, pp. 40–41.

- Silver & Ursini 1997, p. 43.

- Marigny 1994, pp. 82–85.

- Silver & Ursini 1997, p. 205.

- Beam, Christopher (20 November 2008). "I Vant To Upend Your Expectations: Why film vampires always break all the vampire rules". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- Keatley, Avery. "Try as she might, Bram Stoker's widow couldn't kill 'Nosferatu'". NPR.org. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- Eisenberg, Eric (12 May 2021). "Adapting Stephen King's Salem's Lot: How Does The Vampiric Terror Of 1979's TV Miniseries Hold Up?". Cinemablend. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- Marigny 1994, pp. 92–95.

- Silver & Ursini 1997, p. 208.

- Germania, Monica (2012): Being Human? Twenty-First-Century Monsters. In: Edwards, Justin & Monnet, Agnieszka Soltysik (Publisher): The Gothic in Contemporary Literature and Popular Culture: Pop Goth. New York: Taylor, pp. 57–70

- Dan Martin (19 June 2014). "Top-10 most important vampire programs in TV history". Cleveland.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- Bartlett, Wayne; Flavia Idriceanu (2005). Legends of Blood: The Vampire in History and Myth. London: NPI Media Group. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-7509-3736-8.

- Joshi, S. T. (2007). Icons of horror and the supernatural. Vol. 2. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 645–646. ISBN 978-0-313-33782-6. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- Grebey, James (3 June 2019). "How Dungeons and Dragons reimagines and customizes iconic folklore monsters". SyfyWire. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Skal, David J. (1993). The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror. New York: Penguin. pp. 342–343. ISBN 978-0-14-024002-3.

- Jøn, A. Asbjørn (2002). "The Psychic Vampire and Vampyre Subculture". Australian Folklore: A Yearly Journal of Folklore Studies (12): 143–148. ISSN 0819-0852. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Benecke, Mark; Fischer, Ines (2015). Vampyres among us! – Volume III: Quantitative Study of Central European 'Vampyre' Subculture Members. Roter Drache. ISBN 978-3-939459-95-8. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

Cited texts

- Barber, Paul (1988). Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality. New York: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04126-2.

- Bunson, Matthew (1993). The Vampire Encyclopedia. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27748-5.

- Cohen, Daniel (1989). The Encyclopedia of Monsters: Bigfoot, Chinese Wildman, Nessie, Sea Ape, Werewolf and many more …. London: Michael O'Mara Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-948397-94-3.

- Graves, Robert (1990) [1955]. The Greek Myths. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-001026-8.

- Hoyt, Olga (1984). "The Monk's Investigation". Lust for Blood: The Consuming Story of Vampires. Chelsea: Scarborough House. ISBN 978-0-8128-8511-8.

- Jones, Ernest (1931). "The Vampire". On the Nightmare. London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis. ISBN 978-0-394-54835-7. OCLC 2382718.

- Marigny, Jean (1994). Vampires: The World of the Undead. "New Horizons" series. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-30041-1.

- Skal, David J. (1996). V is for Vampire. New York: Plume. ISBN 978-0-452-27173-9.

- Silver, Alain; James Ursini (1993). The Vampire Film: From Nosferatu to Bram Stoker's Dracula. New York: Limelight. ISBN 978-0-87910-170-1.

External links

| Library resources about Vampire |