Violence against women

Violence against women (VAW), also known as gender-based violence[1][2] and sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV),[3] are violent acts primarily or exclusively committed by men or boys against women or girls. Such violence is often considered a form of hate crime,[4] committed against women or girls specifically because they are female, and can take many forms.

| Part of a series on |

| Violence against women |

|---|

| Killing |

| Sexual assault and rape |

| Disfigurement |

| Other issues |

| International legal framework |

| Related topics |

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

VAW has a very long history, though the incidents and intensity of such violence have varied over time and even today vary between societies. Such violence is often seen as a mechanism for the subjugation of women, whether in society in general or in an interpersonal relationship. Such violence may arise from a sense of entitlement, superiority, misogyny or similar attitudes in the perpetrator or his violent nature, especially against women.

The UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women states, "violence against women is a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women" and "violence against women is one of the crucial social mechanisms by which women are forced into a subordinate position compared with men."[5]

Kofi Annan, Secretary-General of the United Nations, declared in a 2006 report posted on the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) website:

Violence against women and girls is a problem of pandemic proportions. At least one out of every three women around the world has been beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused in her lifetime with the abuser usually someone known to her.[6]

Definition

A number of international instruments that aim to eliminate violence against women and domestic violence have been enacted by various international bodies. These generally start with a definition of what such violence is, with a view to combating such practices. The Istanbul Convention (Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence) of the Council of Europe describes VAW "as a violation of human rights and a form of discrimination against women" and defines VAW as "all acts of gender-based violence that result in or are likely to result in physical, sexual, psychological, or economic harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life".[7]

The 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) of the United Nations General Assembly makes recommendations relating to VAW,[8] and the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action mentions VAW.[9] However, the 1993 United Nations General Assembly resolution on the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women was the first international instrument to explicitly define VAW and elaborate on the subject.[10] Other definitions of VAW are set out in the 1994 Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women[11] and by the 2003 Maputo Protocol.[12]

In addition, the term gender-based violence refers to "any acts or threats of acts intended to hurt or make women suffer physically, sexually, or psychologically, and which affect women because they are women or affect women disproportionately".[13] Gender-based violence is often used interchangeably with violence against women,[1] and some articles on VAW reiterate these conceptions by stating that men are the main perpetrators of this violence.[14] Moreover, the definition stated by the 1993 Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women also supported the notion that violence is rooted in the inequality between men and women when the term violence is used together with the term gender-based.[1]

In Recommendation Rec(2002)5 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on the protection of women against violence, the Council of Europe stipulated that VAW "includes, but is not limited to, the following":[15]

- a. violence occurring in the family or domestic unit, including, inter alia, physical and mental aggression, emotional and psychological abuse, rape and sexual abuse, incest, rape between spouses, regular or occasional partners and cohabitants, crimes committed in the name of honour, female genital and sexual mutilation and other traditional practices harmful to women such as forced marriages;

- b. violence occurring within the general community including, inter alia, rape, sexual abuse, sexual harassment and intimidation at work, in institutions or elsewhere trafficking in women for the purposes of sexual exploitation, and economic exploitation and sex tourism;

- c. violence perpetrated or condoned by the state or its officials;

- d. violation of the human rights of women in situations of armed conflict, in particular the taking of hostages, forced displacement, systematic rape, sexual slavery, forced pregnancy, and trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation and economic exploitation.

These definitions of VAW as being gender-based are seen by some to be unsatisfactory and problematic. These definitions are conceptualized in an understanding of society as patriarchal, signifying unequal relations between men and women.[16] Opponents of such definitions argue that the definitions disregard violence against men and that the term gender, as used in gender based violence, only refers to women. Other critics argue that employing the term gender in this particular way may introduce notions of inferiority and subordination for femininity and superiority for masculinity.[17][18] There is no widely accepted current definition that covers all the dimensions of gender-based violence rather than the one for women that tends to reproduce the concept of binary oppositions: masculinity versus femininity.[19]

| Document | Adopted by | Date | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Recommendation 19 | CEDAW Committee | 1992 | 'The definition of discrimination includes gender-based violence, that is, violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately.'[20] |

| DEVAW | United Nations | 20 December 1993 | '...the term "violence against women" means any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women'.[21] |

| Belém do Pará Convention | Organization of American States | 9 June 1994 | '...violence against women shall be understood as any act or conduct, based on gender, which causes death or physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, whether in the public or the private sphere.'[22] |

| Maputo Protocol | African Union | 11 July 2003 | '"Violence against women" means all acts perpetrated against women which cause or could cause them physical, sexual, psychological, and economic harm, including the threat to take such acts; or to undertake the imposition of arbitrary restrictions on or deprivation of fundamental freedoms in private or public life in peace time and during situations of armed conflicts or of war...'[23] |

| Istanbul Convention | Council of Europe | 11 May 2011 | '..."violence against women" is understood as a violation of human rights and a form of discrimination against women and shall mean all acts of gender-based violence that result in, or are likely to result in, physical, sexual, psychological or economic harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life; ... "gender" shall mean the socially constructed roles, behaviours, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for women and men; "gender-based violence against women" shall mean violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately...'. The preamble notes: '...Recognising that women and girls are exposed to a higher risk of gender-based violence than men; Recognising that domestic violence affects women disproportionately, and that men may also be victims of domestic violence...'[24] |

Sexual violence

Sexual harassment can be used to refer to any unwelcome range of actions with sexual overtones, including verbal transgressions.[25] Sexual violence refers to the use of violence to obtain a sexual act, including, for example, trafficking.[26][27] Sexual assault is forcing a physical sexual act on someone against their will,[28] and when this involves sexual penetration or sexual intercourse it is referred to as rape.

Women are most often the victims of rape, which is usually perpetrated by men known to them.[29] The rate of reporting, prosecution and convictions for rape varies considerably in different jurisdictions, and reflects to some extent the society's attitudes to such crimes. It is considered the most underreported violent crime.[30][31] Following a rape, a victim may face violence or threats of violence from the rapist, and, in many cultures, from the victim's own family and relatives. Violence or intimidation of the victim may be perpetrated by the rapist or by friends and relatives of the rapist, as a way of preventing the victims from reporting the rape, of punishing them for reporting it, or of forcing them to withdraw the complaint; or it may be perpetrated by the relatives of the victim as a punishment for "bringing shame" to the family. Internationally, the incidence of rapes recorded by police during 2008 varied between 0.1 per 100,000 people in Egypt and 91.6 per 100,000 people in Lesotho with 4.9 per 100,000 people in Lithuania as the median.[32] In some countries, rape is not reported or properly recorded by police because of the consequences on the victim and the stigma attached to it.

Survival sex

Women who are sex workers end up in the profession for several reasons. Some were victims of sexual and domestic abuse. Many women have said they were raped as working girls. They may be apprehensive about coming forward and reporting their attacks. When reported, many women have said that the stigma was too great and that the police told them they deserved it and were reluctant to follow police policy. Decriminilazing sex work is argued to help sex workers in this aspect.[33]

In some countries it is common for older men to engage in "compensated dating" with underage girls. Such relationships are called enjo kōsai in Japan, and are also common in Asian countries such as Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong. The WHO condemned "economically coerced sex (e.g. school girls having sex with "sugar daddies" (Sugar baby in return for school fees)" as a form of violence against women.[34]

Women from lower certain castes have been involved in prostitution as part of tradition, called Intergenerational prostitution. In pre-modern Korea, women from the lower caste Cheonmin, known as Kisaeng, were trained to provide entertainment, conversation, and sexual services to men of the upper class.[35] In South Asia, castes associated with prostitution today include the Bedias,[36] the Perna caste,[37] the Banchhada,[38] the Nat caste and, in Nepal, the Badi people.[39][40]

Women with illegal resident status are disproportionately involved with prostitution. For example, in 1997, Le Monde diplomatique stated that 80% of prostitutes in Amsterdam were foreigners and 70% had no immigration papers.[41]

Forced sexual services

By military forces

Militarism produces special environments that allow for increased violence against women. War rapes have accompanied warfare in virtually every known historical era.[42] Rape in the course of war is mentioned multiple times in the Bible: "For I will gather all the nations against Jerusalem to battle, and the city shall be taken and the houses plundered and the women raped..."Zechariah 14:2 "Their little children will be dashed to death before their eyes. Their homes will be sacked, and their wives will be raped."Isaiah 13:16

War rapes are rapes committed by soldiers, other combatants or civilians during armed conflict or war, or during military occupation, distinguished from sexual assaults and rape committed amongst troops in military service. It also covers the situation where women are forced into prostitution or sexual slavery by an occupying power. During World War II the Japanese military established brothels filled with "comfort women", girls and women who were forced into sexual slavery for soldiers, exploiting women for the purpose of creating access and entitlement for men.[43][44] People rarely tried to explain why rape happens in wars. One explanation that was floated around was that men in war have "urges".[45]

Another example of violence against women incited by militarism during war took place in the Kovno Ghetto. Jewish male prisoners had access to (and used) Jewish women forced into camp brothels by the Nazis, who also used them.[46]

Rape during the Bangladesh Liberation War by members of the Pakistani military and the militias that supported them led to 200,000 women raped over a period of nine months. Rape during the Bosnian War was used as a highly systematized instrument of war by Serb armed forces predominantly targeting women and girls of the Bosniak ethnic group for physical and moral destruction. Estimates of the number of women raped during the war range from 50,000 to 60,000; as of 2010 only 12 cases have been prosecuted.[47]

The 1998 International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda recognized rape in the Rwandan Genocide as a war crime. Presiding judge Navanethem Pillay said in a statement after the verdict: "From time immemorial, rape has been regarded as spoils of war. Now it will be considered a war crime. We want to send out a strong message that rape is no longer a trophy of war."[48]

According to one report, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant's capture of Iraqi cities in June 2014 was accompanied by an upsurge in crimes against women, including kidnap and rape.[49] The Guardian reported that ISIL's extremist agenda extended to women's bodies and that women living under their control were being captured and raped.[50] Fighters are told that they are free to have sex and rape non-Muslim captive women.[51] Yazidi girls in Iraq allegedly raped by ISIL fighters committed suicide by jumping to their death from Mount Sinjar, as described in a witness statement.[52] Haleh Esfandiari from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars has highlighted the abuse of local women by ISIL militants after they have captured an area. "They usually take the older women to a makeshift slave market and try to sell them. The younger girls ... are raped or married off to fighters", she said, adding, "It's based on temporary marriages, and once these fighters have had sex with these young girls, they just pass them on to other fighters."[53] Describing the Yazidi women captured by ISIS, Nazand Begikhani said "[t]hese women have been treated like cattle... They have been subjected to physical and sexual violence, including systematic rape and sex slavery. They've been exposed in markets in Mosul and in Raqqa, Syria, carrying price tags."[54] In December 2014 the Iraqi Ministry of Human Rights announced that the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant had killed over 150 women and girls in Fallujah who refused to participate in sexual jihad.[55]

During the Rohingya genocide (2016–present) the Armed Forces of Myanmar, along with the Myanmar Border Guard Police and Buddhist militias of Rakhine, committed widespread gang rapes and other forms of sexual violence against the Rohingya Muslim women and girls. A January 2018 study estimated that the military and local Rakhine Buddhists perpetrated gang rapes and other forms of sexual violence against 18,000 Rohingya Muslim women and girls.[56] The Human Rights Watch stated that the gang rapes and sexual violence were committed as part of the military's ethnic cleansing campaign while the United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary General on Sexual Violence in Conflict Pramila Patten said that the Rohingya women and girls were made the "systematic" target of rapes and sexual violence because of their ethnic identity and religion. Other forms of sexual violence included sexual slavery in military captivity, forced public nudity, and humiliation.[57] Some women and girls were raped to death while others were found traumatised with raw wounds after they had arrived in refugee camps in Bangladesh. Human Rights Watch reported of a 15-year-old girl who was ruthlessly dragged on the ground for over 50 feet and then was raped by 10 Burmese soldiers.[58][59]

By criminal groups

Human trafficking refers to the acquisition of persons by improper means such as force, fraud or deception, with the aim of exploiting them.[60] The Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children states,[61]

"Trafficking in persons" shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.

Because of the illegal nature of trafficking, reliable data on its extent is very limited.[62] The WHO states "Current evidence strongly suggests that those who are trafficked into the sex industry and as domestic servants are more likely to be women and children."[62] A 2006 study in Europe on trafficked women found that the women were subjected to serious forms of abuse, such as physical or sexual violence, that affected their physical and mental health.[62]

Forced prostitution is prostitution that takes place as a result of coercion by a third party. In forced prostitution, the party/parties who force the victim to be subjected to unwanted sexual acts exercise control over the victim.[63]

Intimate partner related violence

While "domestic violence" or "family violence" can be used to refer to violence between any family members, intimate partner violence refers to violence between intimate partners.

Violence related to acquiring a partner

Single women and women who are economically independent have been vilified by certain groups of men. In Hassi Messaoud in Algeria in 2001, mobs targeted single women, attacking 95 and killing at least six[64][65] and, in 2011, similar attacks happened again throughout Algeria.[66][67]

Stalking is unwanted or obsessive attention by an individual or group toward another person, often manifested through persistent harassment, intimidation, or following/monitoring of the victim. Stalking is often understood as "course of conduct directed at a specific person that would cause a reasonable person to feel fear".[68] Although stalkers are frequently portrayed as being strangers, they are most often known people, such as former or current partners, friends, colleagues or acquaintances. In the U.S., a survey by NVAW found that only 23% of female victims were stalked by strangers.[69] Stalking by partners can be very dangerous, as sometimes it can escalate into severe violence, including murder.[69] Police statistics from the 1990s in Australia indicated that 87.7% of stalking offenders were male and 82.4% of stalking victims were female.[70]

An acid attack is the act of throwing acid onto someone with the intention of injuring or disfiguring them. Women and girls are the victims in 75-80% of cases,[71] and are often connected to domestic disputes, including dowry disputes, and refusal of a proposal of marriage, or of sexual advances.[72] The acid is usually thrown at the faces, burning the tissue, often exposing and sometimes dissolving the bones.[73] The long term consequences of these attacks include blindness and permanent scarring of the face and body.[74][75] Such attacks are common in South Asia, in countries such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, India; and in Southeast Asia, especially in Cambodia.[76]

Forced marriage

._Molla_Nasreddin.jpg.webp)

A forced marriage is a marriage in which one or both of the parties is married against their will. Forced marriages are common in South Asia, the Middle East and Africa. The customs of bride price and dowry, that exist in many parts of the world, contribute to this practice. A forced marriage is also often the result of a dispute between families, where the dispute is 'resolved' by giving a female from one family to the other.[77]

The custom of bride kidnapping continues to exist in some Central Asian countries such as Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and the Caucasus, or parts of Africa, especially Ethiopia. A girl or a woman is abducted by the would be groom, who is often helped by his friends. The victim is often raped by the would be groom, after which he may try to negotiate a bride price with the village elders to legitimize the marriage.[78]

Forced and child marriages are practiced by some inhabitants in Tanzania. Girls are sold by their families to older men for financial benefits and often girls are married off as soon as they hit puberty, which can be as young as seven years old.[79] To the older men, these young brides act as symbols of masculinity and accomplishment. Child brides endure forced sex, causing health risks and growth impediments.[80] Primary education is usually not completed for young girls in forced marriages. Married and pregnant students are often discriminated against, and expelled and excluded from school.[79] The Law of Marriage Act currently does not address issues with guardianship and child marriage. The issue of child marriage is not addressed enough in this law, and only establishes a minimum age of 18 for the boys of Tanzania. A minimum age needs to be enforced for girls to stop these practices and provide them with equal rights and a less harmful life.[81]

Dowry violence

The custom of dowry, which is common in South Asia, especially in India, is the trigger of many forms of violence against women. Bride burning is a form of violence against women in which a bride is killed at home by her husband or husband's family due to his dissatisfaction over the dowry provided by her family. Dowry death refers to the phenomenon of women and girls being killed or committing suicide due to disputes regarding dowry. Dowry violence is common in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal. In India, in 2011 alone, the National Crime Records Bureau reported 8,618 dowry deaths, while unofficial figures suggest the numbers to be at least three times higher.[82]

Violence within a relationship

.jpg.webp)

The relation between violence against women and marriage laws, regulations and traditions has also been discussed.[83][84] Roman law gave men the right to chastise their wives, even to the point of death.[85] The US and English law subscribed until the 20th century to the system of coverture, that is, a legal doctrine under which, upon marriage, a woman's legal rights were subsumed by those of her husband.[86] Common-law in the United States and in the UK allowed for domestic violence[87] and in the UK, before 1891, the husband had the right to inflict moderate corporal punishment on his wife to keep her "within the bounds of duty".[88][89] Today, outside the West, many countries severely restrict the rights of married women: for example, in Yemen, marriage regulations state that a wife must obey her husband and must not leave home without his permission.[90] In Iraq husbands have a legal right to "punish" their wives. The criminal code states at Paragraph 41 that there is no crime if an act is committed while exercising a legal right; examples of legal rights include: "The punishment of a wife by her husband, the disciplining by parents and teachers of children under their authority within certain limits prescribed by law or by custom".[91] In the West, married women faced discrimination until just a few decades ago: for instance, in France, married women received the right to work without their husband's permission in 1965.[92] In Spain, during the Franco era, a married woman required her husband's consent (permiso marital) for nearly all economic activities, including employment, ownership of property and traveling away from home; the permiso marital was abolished in 1975.[93] Concerns exist about violence related to marriage – both inside marriage (physical abuse, sexual violence, restriction of liberty) and in relation to marriage customs (dowry, bride price, forced marriage, child marriage, marriage by abduction, violence related to female premarital virginity). Claudia Card, professor of philosophy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, writes:[94]

- The legal rights of access that married partners have to each other's persons, property, and lives makes it all but impossible for a spouse to defend herself (or himself), or to be protected against torture, rape, battery, stalking, mayhem, or murder by the other spouse... Legal marriage thus enlists state support for conditions conducive to murder and mayhem.

Physical

Women are more likely to be victimized by someone that they are intimate with, commonly called "intimate partner violence" (IPV). Instances of IPV tend not to be reported to police and thus many experts find it hard to estimate the true magnitude of the problem.[95] Though this form of violence is often considered as an issue within the context of heterosexual relationships, it also occurs in lesbian relationships,[96] daughter-mother relationships, roommate relationships and other domestic relationships involving two women. Violence against women in lesbian relationships is about as common as violence against women in heterosexual relationships.[97]

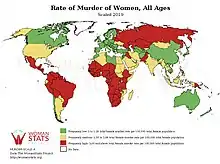

Women are much more likely than men to be murdered by an intimate partner. In the United States, in 2005, 1181 women were killed by their intimate partners, compared to 329 men.[98][99] It is estimated that 30% or more of the women who are admitted to the ER could be victims of domestic violence

[100] In England and Wales about 100 women are killed by partners or former partners each year while 21 men were killed in 2010.[101] In 2008, in France, 156 women were killed by their intimate partner, compared to 27 men.[102] According to the WHO, globally, as many as 38% of murders of women are committed by an intimate partner.[103] A UN report compiled from a number of different studies conducted in at least 71 countries found domestic violence against women to be most prevalent in Ethiopia.[104] A study by Pan American Health Organization conducted in 12 Latin American countries found the highest prevalence of domestic violence against women to be in Bolivia.[105] In Western Europe, a country that has received major international criticism for the way it has dealt legally with the issue of violence against women is Finland; with authors pointing out that a high level of equality for women in the public sphere (as in Finland) should never be equated with equality in all other aspects of women's lives.[106][107][108]

The American Psychiatric Association planning and research committees for the forthcoming DSM-5 (2013) have canvassed a series of new Relational disorders, which include Marital Conflict Disorder Without Violence or Marital Abuse Disorder (Marital Conflict Disorder With Violence).[109]: 164, 166 Couples with marital disorders sometimes come to clinical attention because the couple recognize long-standing dissatisfaction with their marriage and come to the clinician on their own initiative or are referred by an astute health care professional. Secondly, there is serious violence in the marriage that is "usually the husband battering the wife".[109]: 163 In these cases the emergency room or a legal authority often is the first to notify the clinician. Most importantly, marital violence "is a major risk factor for serious injury and even death and women in violent marriages are at much greater risk of being seriously injured or killed (National Advisory Council on Violence Against Women 2000)".[109]: 166 The authors of this study add, "There is current considerable controversy over whether male-to-female marital violence is best regarded as a reflection of male psychopathology and control or whether there is an empirical base and clinical utility for conceptualizing these patterns as relational."[109]: 166

Recommendations for clinicians making a diagnosis of Marital Relational Disorder should include the assessment of actual or "potential" male violence as regularly as they assess the potential for suicide in depressed patients. Further, "clinicians should not relax their vigilance after a battered wife leaves her husband, because some data suggest that the period immediately following a marital separation is the period of greatest risk for the women. Many men will stalk and batter their wives in an effort to get them to return or punish them for leaving. Initial assessments of the potential for violence in a marriage can be supplemented by standardized interviews and questionnaires, which have been reliable and valid aids in exploring marital violence more systematically."[109]: 166

The authors conclude with what they call "very recent information"[109]: 167, 168 on the course of violent marriages, which suggests that "over time a husband's battering may abate somewhat, but perhaps because he has successfully intimidated his wife. The risk of violence remains strong in a marriage in which it has been a feature in the past. Thus, treatment is essential here; the clinician cannot just wait and watch."[109]: 167, 168 The most urgent clinical priority is the protection of the wife because she is the one most frequently at risk, and clinicians must be aware that supporting assertiveness by a battered wife may lead to more beatings or even death.[109]: 167, 168

Sexual

Marital or spousal rape was once widely condoned or ignored by law, and is now widely considered an unacceptable violence against women and repudiated by international conventions and increasingly criminalized. Still, in many countries, spousal rape either remains legal, or is illegal but widely tolerated and accepted as a husband's prerogative. The criminalization of spousal rape is recent, having occurred during the past few decades. Traditional understanding and views of marriage, rape, sexuality, gender roles and self determination have started to be challenged in most Western countries during the 1960s and 1970s, which has led to the subsequent criminalization of marital rape during the following decades. With a few notable exceptions, it was during the past 30 years that most laws against marital rape have been enacted. Some countries in Scandinavia and in the former Communist Bloc of Europe made spousal rape illegal before 1970, but most Western countries criminalized it only in the 1980s and 1990s. In many parts of the world the laws against marital rape are very new, having been enacted in the 2000s.

In Canada, marital rape was made illegal in 1983, when several legal changes were made, including changing the rape statute to sexual assault, and making the laws gender neutral.[110][111][112] In Ireland, spousal rape was outlawed in 1990.[113] In the US, the criminalization of marital rape started in the mid-1970s and in 1993 North Carolina became the last state to make marital rape illegal.[114] In England and Wales, marital rape was made illegal in 1991. The views of Sir Matthew Hale, a 17th-century jurist, published in The History of the Pleas of the Crown (1736), stated that a husband cannot be guilty of the rape of his wife because the wife "hath given up herself in this kind to her husband, which she cannot retract"; in England and Wales this would remain law for more than 250 years, until it was abolished by the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords, in the case of R v R in 1991.[115] In the Netherlands marital rape was also made illegal in 1991.[116] One of the last Western countries to criminalize marital rape was Germany, in 1997.[117]

The relation between some religions (Christianity and Islam) and marital rape is controversial. The Bible at 1 Corinthians 7:3-5 explains that one has a "conjugal duty" to have sexual relations with one's spouse (in sharp opposition to sex outside marriage, which is considered a sin) and states, "The wife does not have authority over her own body, but the husband does. And likewise the husband does not have authority over his own body, but the wife does. Do not deprive one another..."[118] Some conservative religious figures interpret this as rejecting to possibility of marital rape.[119] Islam makes reference to sexual relations in marriage too, notably: "Allah's Apostle said, 'If a husband calls his wife to his bed (i.e. to have sexual relation) and she refuses and causes him to sleep in anger, the angels will curse her till morning';"[120] and several comments on the issue of marital rape made by Muslim religious leaders have been criticized.[121][122]

Dating abuse or dating violence is the perpetration of coercion, intimidation or assault in the context of dating or courtship. It is also when one partner tries to maintain abusive power and control. Dating violence is defined by the CDC as "the physical, sexual, psychological, or emotional violence within a dating relationship, including stalking".[123]

Widowhood related violence

Widows have been subjected to forced remarriage called widow inheritance, where she is forced to marry a male relative of her late husband.[124] Another practice is banned remarriage of widows, such as was legal in India[125] and Korea.[126] A more extreme version is the ritual killing of widows as was seen in India and Fiji. Sati is the burning of widows and although sati in India is today an almost defunct practice, isolated incidents have occurred in recent years, such as the 1987 sati of Roop Kanwar, as well as several incidents in rural areas in 2002,[127] and 2006.[128] A traditional idea upheld in some places in Africa is that an unmarried widow is unholy and “disturbed” if she is unmarried and abstains from sex for some period of time. This fuels the practice of widow cleansing where the unmarried widow is required to have sexual intercourse as a form of ritual purification and is commenced with a ceremony for the neighborhood to witness that she is now purified.[129]

Unmarried widows are most likely to be accused and killed as witches.[130][131] Witch trials in the early modern period (between the 15th and 18th centuries) were common in Europe and in the European colonies in North America. Today, there remain regions of the world (such as parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, rural North India, and Papua New Guinea) where belief in witchcraft is held by many people, and women accused of being witches are subjected to serious violence.[132]

Non-intimate partner family violence

Infanticide and abandonment

Son preference is a custom prevalent in many societies[133] that in its extreme can lead to the rejection of daughters. Sex-selective abortion of females is more common among the higher income population, who can access medical technology. In China, the one child policy increased sex-selective abortions and was largely responsible for an unbalanced sex ratio. After birth, neglect and diverting resources to male children can lead to some countries having a skewed ratio with more boys than girls,[133] with such practices killing an approximate 230,000 girls under five in India each year.[134] The Dying Rooms is a 1995 television documentary film about Chinese state orphanages, which documented how parents abandoned their newborn girls into orphanages, where the staff would leave the children in rooms to die of thirst, or starvation.

Another manifestation of son preference is the violence inflicted against mothers who give birth to girls.[135]

Genitalia

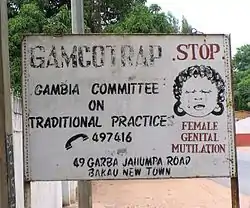

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons".[136]

The WHO states: "The procedure has no health benefits for girls and women" and "Procedures can cause severe bleeding and problems urinating, and later cysts, infections, infertility as well as complications in childbirth increased risk of newborn deaths".[136]

According to a UNICEF report, the top rates for FGM are in Somalia (with 98 percent of women affected), Guinea (96 percent), Djibouti (93 percent), Egypt (91 percent), Eritrea (89 percent), Mali (89 percent), Sierra Leone (88 percent), Sudan (88 percent), Gambia (76 percent), Burkina Faso (76 percent), Ethiopia (74 percent), Mauritania (69 percent), Liberia (66 percent), and Guinea-Bissau (50 percent).[137] FGM is linked to cultural rites and customs, including traditional practices. It continues to take place in different communities of Africa and the Middle East, including in places where it is banned by national legislation. According to a 2013 UNICEF report, 125 million women and girls in Africa and the Middle East have experienced FGM.[137] Due to globalization and immigration, FGM is spreading beyond the borders of Africa and Middle East, to countries such as Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, New Zealand, the U.S., and UK.[138]

Although FGM is today associated with developing countries, this practice was common until the 1970s in parts of the Western world, too. FGM was considered a standard medical procedure in the United States for most of the 19th and 20th centuries.[139] Physicians performed surgeries of varying invasiveness to treat a number of diagnoses, including hysteria, depression, nymphomania, and frigidity. The medicalization of FGM in the United States allowed these practices to continue until the second part of the 20th century, with some procedures covered by Blue Cross Blue Shield Insurance until 1977.[140][139]

As of 2016, in Africa, FGM has been legally banned in Benin, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, and Zambia.[141] The Istanbul Convention prohibits female genital mutilation (Article 38).[142]

Labia stretching, also referred to as labia elongation or labia pulling, is the act of lengthening the labia minora (the inner lips of the female genitals) through manual manipulation (pulling) or physical equipment (such as weights).[143] It is often done by older women to girls.[144]

Feet

.jpg.webp)

Foot-binding was a practice in China done to reduce the size of feet in girls. It was seen as more desirable and was likely to make a more prestigious marriage.[145]

Force-feeding

In some countries, notably Mauritania, young girls are forcibly fattened to prepare them for marriage, because obesity is seen as desirable. This practice of force-feeding is known as leblouh or gavage.[146] The practice goes back to the 11th century, and has been reported to have made a significant comeback after a military junta took over the country in 2008.[147]

Sexual initiation rites

Sexual "cleansing" is ceremony where girls have sexual intercourse as a cleansing ritual following their first menstruation[148] and is referred to as kusasa fumbi in some regions of Malawi.[149] Prepubescent girls are often sent to a training camp where women known as anamkungwi, or "key leaders", teach the girls how to cook, clean, and have sexual intercourse in order to be a wife.[150] After the training, a man known as a hyena performs the cleansing for 12- to 17-year-old females for three days and the girl is sometimes required to perform a bare-breasted dance, known as chisamba, to signal the end of her initiation in front of the community.[151]

Honor killings

Honor killings are a common form of violence against women in certain parts of the world. Honor killings are perpetrated by family members (usually husbands, fathers, uncles or brothers) against women in the family who are believed to have placed dishonor to the family. The death of the dishonorable woman is believed to restore honor.[152] These killings are a traditional practice, believed to have originated from tribal customs where an allegation against a woman can be enough to defile a family's reputation.[153][154] Women are killed for reasons such as refusing to enter an arranged marriage, being in a relationship that is disapproved by their relatives, attempting to leave a marriage, having sex outside marriage, becoming the victim of rape, and dressing in ways that are deemed inappropriate, among others.[153][155] In cultures where female virginity is highly valued and considered mandatory before marriage; in extreme cases, rape victims are killed in honor killings. Victims may also be forced by their families to marry the rapist in order to restore the family's "honor".[156] In Lebanon, the Campaign Against Lebanese Rape Law - Article 522 was launched in December 2016 to abolish the article that permitted a rapist to escape prison by marrying his victim. In Italy, before 1981, the Criminal Code provided for mitigating circumstances in case of a killing of a woman or her sexual partner for reasons related to honor, providing for a reduced sentence. [157][158]

Honor killings are common in countries such as Afghanistan, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, Yemen.[155][159][160][161][162] Honor killings also occur in immigrant communities in Europe, the United States and Canada. Although honor killings are most often associated with the Middle East and South Asia, they occur in other parts of the world too.[153][163] In India, honor killings occur in the northern regions of the country, especially in the states of Punjab, Haryana, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Himachal Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.[164][165] In Turkey, honor killings are a serious problem in Southeastern Anatolia.[166][167]

Pregnancy-related violence

Obstetric violence refers to acts categorized as physically or psychologically violent in the context of labor and birth. A pregnant woman can sometimes be coerced into accepting surgical interventions or are done without her consent.[169][170] This could include the "husband's stitch" in which one or more additional sutures than necessary are used to repair a woman's perineum after it has been torn or cut during childbirth with the intent of tightening the opening of the vagina and thereby enhance the pleasure of her male sex partner during penetrative intercourse. Several Latin American countries have laws to protect against obstetric violence.[171] Reproductive coercion is a collection of behaviors that interfere with decision-making related to reproductive health.[172] According to the WHO, "Discrimination in health care settings takes many forms and is often manifested when an individual or group is denied access to health care services that are otherwise available to others. It can also occur through denial of services that are only needed by certain groups, such as women."[173]

Restrictions around menstruation

Women in some cultures are forced into social isolation during their menstrual periods. In parts of Nepal for instance, they are forced to live in sheds, are forbidden to touch men or even to enter the courtyard of their own homes, and are barred from consuming milk, yogurt, butter, meat, and various other foods, for fear they will contaminate those goods. Women have died during this period because of starvation, bad weather, or bites by snakes.[174] In cultures where women are restricted from being in public places, by law or custom, women who break such restrictions often face violence.[175]

Forced pregnancy

Forced pregnancy is the practice of forcing a woman or girl to become pregnant. A common motivation for this is to help establish a forced marriage, including by means of bride kidnapping. This was also used as part of a program of breeding slaves (see Slave breeding in the United States). In the 20th century, state mandated forced marriage with the aim of increasing the population was practiced by some authoritarian governments, notably during the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, which systematically forced people into marriages ordering them to have children, in order to increase the population and continue the revolution.[176]

The issue of forced continuation of pregnancy (i.e. denying a woman safe and legal abortion) is also seen by some organizations as a violation of women's rights. For example, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women considers the criminalization of abortion a "violations of women's sexual and reproductive health and rights" and a form of "gender based violence".[177]

In addition, in some parts of Latin America, with very strict anti-abortion laws, pregnant women avoid the medical system due to fear of being investigated by the authorities if they have a miscarriage, or a stillbirth, or other problems with the pregnancy. Prosecuting such women is quite common in places such as El Salvador.[178][179][180][181]

Forced sterilization and forced abortion

Forced sterilization and forced abortion are considered forms of gender-based violence.[182] The Istanbul Convention prohibits forced abortion and forced sterilization (Article 39).[183] According to the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women, all "women are guaranteed the right to decide freely and responsibly on the number of and spacing of their children, and to have access to information, education, and means to enable them to exercise these rights."[184]

Studies show forced sterilizations often target socially and politically disadvantaged groups such as racial and ethnic minorities, the poor, and indigenous populations.[185] In the United States, much of the history of forced sterilization is connected to the legacy of eugenics and racism in the United States.[185] Many doctors thought that they were doing the country a service by sterilizing women who were poor, disabled, or a minority; the doctors considered those women to be a drain on the system.[185][186] Native American, Mexican American, African American and Puerto Rican-American women were coerced into sterilization programs, with Native Americans and African Americans especially being targeted.[185] Records have shown that Native American girls as young as eleven years-old had hysterectomy operations performed.[187]

In Europe, there have been a number of lawsuits and accusations towards the Czech Republic and Slovakia of sterilizing Roma women without adequate information and waiting period.[188] In response, both nations have instituted a mandatory seven-day waiting period and written consent. Slovakia has been condemned on the issue of forced sterilization of Roma women several times by the European Court for Human Rights (see V. C. vs. Slovakia, N. B. vs. Slovakia and I.G. and Others vs. Slovakia).

In Peru, in 1995, Alberto Fujimori launched a family planning initiative that especially targeted poor and indigenous women. In total, over 215,000 women were sterilized, with over 200,000 believed to have been coerced.[189] In 2002, Health Minister Fernando Carbone admitted that the government gave misleading information, offered food incentives, and threatened to fine parents if they had additional children. The procedures have also been found to have been negligent, with less than half using proper anesthetic.[190]

In China, the one child policy included forced abortions and forced sterilization.[191] Forced sterilization is also practiced in Uzbekistan.[192][193]

Women-specific state restrictions

Women can be penalized for breaching laws specifically targeting women.

Dress

In Iran, since 1981, after the Islamic Revolution, all women are required to wear loose-fitting clothing and a headscarf in public.[194][195] In 1983, the Islamic Consultative Assembly decided that women who do not cover their hair in public will be punished with 74 lashes. Since 1995, unveiled women can also be imprisoned for up to 60 days.[196] The Iranian protests against compulsory hijab continued into the September 2022 Iranian protests which was triggered in response to the killing of Mahsa Amini, who was allegedly beaten to death by police due to wearing an "improper hijab". In Saudi Arabia, after the Grand Mosque seizure of 1979, it became mandatory for women to veil in public[197] but this was no longer required since 2018. [198] In Afghanistan, since May 2022, women are required to wear a hijab and face covering in public. [199]

The hijab has seen bans in places such as Austria,[200] Yugoslavia, [201] Kosovo,[202] Kazakhstan,[203] the Soviet Union,[204] and Tunisia.[205] On 8 January 1936,[206] Reza Shah issued a decree, Kashf-e hijab, banning all veils.[195] To enforce this decree, the police were ordered to physically remove the veil from any woman who wore it in public. Women who refused were beaten, their headscarves and chadors torn off, and their homes forcibly searched.[207]

Freedom of movement

Women are, in many parts of the world, severely restricted in their freedom of movement. Freedom of movement is an essential right, recognized by international instruments, including Article 15 (4) of CEDAW.[208] Nevertheless, in some countries, women are not legally allowed to leave home without a male guardian (male relative or husband).[209] Saudi Arabia was the only country in the world where women were forbidden to drive motor vehicles until June 2018.[210]

Sexuality

Sex crimes such as adultery and sex outside marriage are disproportionately levelled against women and the punishment is often stoning and flogging. This has been seen in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Pakistan, Yemen, the United Arab Emirates, and some states in Nigeria.[211] Additionally this can deter victims of sexual violence from reporting the crime, because the victims may themselves be punished (if they cannot prove their case, if they are deemed to have been in the company of an unrelated male, or if they were unmarried and not virgins at the time of the rape).[212][213] Another aspect is the denial of medical care often occurs with regard to reproductive and sexual health. Sometimes women themselves avoid the medical system for fear of being reported to the police or facing family violence due to having premarital sex or being the victims of sexual violence.

Violence in male-dominated spheres

.jpg.webp)

Violence Against Women in Politics (VAWP)

Violence Against Women in Politics (VAWP) is the act or threat of physical, emotional or psychological violence against female politicians on the basis of their gender, most often with the intent of discouraging the victims and other female politicians from participating in the political process. VAWP has been growing in significance among the fields of gendered political science and feminist political theory studies. The main intent behind creating a separate category that is distinct from Violence Against Women, is to highlight the barriers faced by women who work in politics, or wish to pursue a career in the political realm. VAWP is unique from Violence Against Women in three important ways: victims are targeted because of their gender; the violence itself can be gendered (i.e., sexism, sexual violence); the primary goal is to deter women from participating in politics (including but not limited to voting, running for office, campaigning, etc.).[214] It is also important to distinguish VAWP from political violence, which is defined by the use or threats of force to reach political ends, and can be experienced by all politicians.[215] It is also important to distinguish VAWP from political violence, which is defined by the use or threats of force to reach political ends, and can be experienced by all politicians.[215] While women's participation in national parliaments has been increasing, rising from 11% in 1995 to 25% in 2021, there is still a large disparity between male and female representation in governmental politics.[216] Expanding women's participation in government is a crucial goal for many countries, as female politicians have proven invaluable with respect to bringing certain issues to the forefront, such as elimination of gender-based violence, parental leave and childcare, pensions, gender-equality laws, electoral reform, and providing fresh perspectives on numerous policy areas that have typically remained a male-dominated realm.[216] In order to increase women's participation in an effective manner, the importance of recognizing the issues related to VAWP and making every effort to provide the necessary resources to victims and condemn any and all hostile behaviour in political institutions cannot be understated. Experiencing VAWP can dissuade women from remaining in politics (and lead to an early exit from their career or from aspiring higher political office. Witnessing women in politics experience VAWP can serve as one of many deterrents for aspirants to run for office and for candidates to continue campaigning.[215] Acts of violence or harassment are often not deemed to be gendered when they are reported, if they are reported at all. VAWP is often dismissed as "the cost of doing politics" and reporting can be seen as "political suicide," which contributes to the normalization of VAWP.[215] This ambiguity results in a lack of information regarding attacks and makes the issue appear to be relatively commonplace. While it is reported that women in politics are more often targeted by violence than their male counterparts,[217] the specific cause is often not reported as a gendered crime. This makes it more difficult to pinpoint where the links between gender-specific violence and political violence really are. In many countries, the practice of electoral politics is traditionally considered to be a masculine domain.[218] The history of male dominated politics has allowed some male politicians to believe they have a right to participate in politics while women should not, since women's participation is a threat to the social order. Male politicians sometimes feel threatened by the prospect of a female politician occupying their position, which can cause them to lash out, and weak men do not want to feel as though women could be above them causing them to harass and threaten women in power. 48% of electoral violence against women is against supporters, this is most likely the largest percentage as it has the largest amount of the public participating. 9% of electoral violence against women is targeting candidates, while 22% targets female voters. This means that women who are directly acting in politics are likely to face some form of violence, whether physical or emotional.[219] Regarding violence against female politicians, younger women and those with intersecting identities, particularly racial and ethnic minorities, are more likely to be targets. Female politicians who outwardly express and act from feminist perspectives are also more likely to be victimized.[215]

Sub-Types of VAWP

Gabrielle Bardell's 2011 report: "Breaking the mold: Understanding Gender and Electoral Violence" was one of the first documents published that showed examples and figures for how women are intimidated and attacked in politics.[219] Since Bardall's report, other scholars have conducted further research on the topic. Notably, Mona Lena Krook's work on VAWP introduced 5 forms of violence and harassment: physical, sexual, psychological, economic, and semiotic/symbolic. Physical violence encompasses inflicting, or attempting to inflict, bodily harm and injury.[215][220] While physical violence is the most easily identified form, it is actually the least common type. [215]Sexual violence involves (attempts at) sexual acts through coercion, including unwanted sexual comments, advances, and harassment.[215][220] Psychological violence includes causing emotional and mental damage through means of death/rape threats, stalking, etc.[215][220] Economic violence involves denying, withholding, and controlling female politicians’ access to financial resources, particularly regarding campaigns.[215][220] Semiotic or symbolic violence, the most abstract subtype of VAWP, refers to the erasure of female politicians through degrading images and sexist language.[215][220][221] Krook theorizes that semiotic violence against women in politics works in two related ways: rendering women invisible and rendering women incompetent. By symbolically removing women from the public political sphere, semiotic violence renders women invisible. Examples include using masculine grammar when speaking about and to political women, interrupting female politicians, and not portraying political women in the media. By highlighting the role incongruity between stereotypically feminine attributes (e.g., warm, polite, submissive), and traits typically ascribed to good leaders (e.g., strong, powerful, assertive), semiotic violence emphasizes that women are incompetent to be political actors.[221] This form of semiotic violence can manifest through denying and minimizing women's political qualifications, sexual objectification, and labeling political women as emotional, among other actions.[221]

Higher education

Sexual violence on college campuses is considered a major problem in the United States. According to the conclusion of a major Campus Sexual Assault (CSA) Study: "The CSA Study data suggest women at universities are at considerable risk for experiencing sexual assault."[222] Sexual violence on campus has been researched in other countries too, such as Canada,[223] the UK,[224] and New Zealand.[225]

Sports

Sport-related violence against women is any physical, sexual, mental acts that are "perpetrated by both male athletes and by male fans or consumers of sport and sporting events, as well as by coaches of female athletes".[226] The documenting reports and literature suggest that there are obvious connections between contemporary sport and violence against women. Such events as the 2010 World Cup, the Olympic and Commonwealth Games "have highlighted the connections between sports spectatorship and intimate partner violence, and the need for police, authorities and services to be aware of this when planning sporting events".[226] Sport-related violence occurs in various contexts and places, including homes, pubs, clubs, hotel rooms, the streets.[226] Violence against women is a topic of concern in the United States' collegiate athletic community. From the 2010 UVA lacrosse murder, in which a male athlete was charged guilty with second degree murder of his girlfriend, to the 2004 University of Colorado Football Scandal when players were charged with nine alleged sexual assaults,[227] studies suggest that athletes are at higher risk for committing sexual assault against women than the average student.[228][229] It is reported that one in three college assaults are committed by athletes.[230] Surveys suggest that male student athletes who represent 3.3% of the college population, commit 19% of reported sexual assaults and 35% of domestic violence.[231] The theories that surround these statistics range from misrepresentation of the student-athlete to an unhealthy mentality towards women within the team itself.[230] Sociologist Timothy Curry, after conducting an observational analysis of two big time sports' locker room conversations, deduced that the high risk of male student athletes for gender abuse is a result of the team's subculture.[232] Curry states, "Their locker room talk generally treated women as objects, encouraged sexist attitudes toward women and, in its extreme, promoted rape culture."[232] He proposes that this objectification is a way for the male to reaffirm his heterosexual status and hyper-masculinity. Claims have been made that the atmosphere changes when an outsider (especially women) intrude in the locker room. In the wake of the reporter Lisa Olson being harassed by a Patriots player in the locker room in 1990, she said, "We are taught to think we must have done something wrong and it took me a while to realize I hadn't done anything wrong."[233] Other female sports reporters (college and professional) have said that they often brush off the players' comments, which leads to further objectification.[233] Some sociologists challenge this assertion. Steve Chandler says that because of their celebrity status on campus, "athletes are more likely to be scrutinized or falsely accused than non-athletes."[229] Stephanie Mak says that "if one considers the 1998 estimates that about three million women were battered and almost one million raped, the proportion of incidences that involve athletes in comparison to the regular population is relatively small."[230] In response to the proposed link between college athletes and gender-based violence, and media coverage holding Universities as responsible for these scandals more universities are requiring athletes to attend workshops that promote awareness. For example, St. John's University holds sexual assault awareness classes in the fall for its incoming student athletes.[234] Other groups, such as the National Coalition Against Violent Athletes, have formed to provide support for the victims as their mission statement reads, "The NCAVA works to eliminate off the field violence by athletes through the implementation of prevention methods that recognize and promote the positive leadership potential of athletes within their communities. In order to eliminate violence, the NCAVA is dedicated to empowering individuals affected by athlete violence through comprehensive services including advocacy, education and counseling."[235]

In the military

A 1995 study of female war veterans found that 90 percent had been sexually harassed. A 2003 survey found that 30 percent of female vets said they were raped in the military and a 2004 study of veterans who were seeking help for post-traumatic stress disorder found that 71 percent of the women said they were sexually assaulted or raped while serving.[236]

Online

Cyberbullying is a form of intimidation using electronic forms of contact. In the 21st century, cyberbullying has become increasingly common, especially among teenagers in Western countries.[237] On 24 September 2015, the United Nations Broadband Commission released a report that claimed that almost 75% percent of women online have encountered harassment and threats of violence, otherwise known as cyber violence.[238] Misogynistic rhetoric is prevalent online, and the public debate over gender-based attacks has increased significantly, leading to calls for policy interventions and better responses by social networks like Facebook and Twitter.[239][240] Some specialists have argued that gendered online attacks should be given particular attention within the wider category of hate speech.[241] Abusers quickly identified opportunities online to humiliate their victims, destroy their careers, reputations and relationships, and even drive them to suicide or "trigger so-called 'honor' violence in societies where sex outside of marriage is seen as bringing shame on a family".[242] According to a poll conducted by Amnesty International in 2018 across 8 countries, 23% of women have experienced online abuse of harassment. These are often sexist or misogynistic in nature and include direct of indirect threats of physical or sexual violence, abuse targeting aspects of their personality and privacy violations.[243] According to Human Rights Watch, 90% of those who experienced sexual violence online in 2019 were women and girls.[242]

Effect on society

According to an article published in the Health and Human Rights journal,[244] regardless of many years of advocacy and involvement of many feminist activist organizations, the issue of violence against women still "remains one of the most pervasive forms of human rights violations worldwide".[244]: 91 The violence against women can occur in both public and private spheres of life and at any time of their life span. Violence against women often keeps women from wholly contributing to social, economic, and political development of their communities.[244][245] Many women are terrified by these threats of violence and this essentially influences their lives so that they are impeded to exercise their human rights; for instance, they fear contributing to the development of their communities socially, economically, and politically.[245] Apart from that, the causes that trigger VAW or gender-based violence can go beyond just the issue of gender and into the issues of age, class, culture, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, and specific geographical area of their origins.

Most often, violence against women has been framed as a health issue, and also as a violation of human rights. The research seems to provide convincing evidence that violence against women is a severe and pervasive problem the world over, with devastating effects on the health and well-being of women and children.[246] Importantly, other than the issue of social divisions, gendered violence can also extend into the realm of health issues and become a direct concern of the public health sector.[247] A health issue such as HIV/AIDS is another cause that also leads to violence. Women who have HIV/AIDS infection are also among the targets of the violence.[244]: 91 The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that violence against women puts an undue burden on health care services, as women who have suffered violence are more likely to need health services and at higher cost, compared to women who have not suffered violence.[103] Another statement that confirms an understanding of VAW as being a significant health issue is apparent in the recommendation adopted by the Council of Europe, violence against women in private sphere, at home or domestic violence, is the main reason of "death and disability" among the women who encountered violence.[244]: 91 A study in 2002 estimated that at least one in five women in the world had been physically or sexually abused by a man sometime in their lives, and "gender-based violence accounts for as much death and ill-health in women aged 15–44 years as cancer, and is a greater cause of ill-health than malaria and traffic accidents combined."[248]

In addition, several studies have shown a link between poor treatment of women and international violence. These studies show that one of the best predictors of inter- and intranational violence is the maltreatment of women in the society.[249][250]

Forms of violence

Violence against women can fit into several broad categories. These include violence carried out by individuals as well as states. Some of the forms of violence perpetrated by individuals are: rape, domestic violence, sexual harassment, acid throwing, reproductive coercion, female infanticide, prenatal sex selection, obstetric violence, online gender-based violence and mob violence; as well as harmful customary or traditional practices such as honor killings, dowry violence, female genital mutilation, marriage by abduction and forced marriage. There are forms of violence which may be perpetrated or condoned by the government, such as war rape; sexual violence and sexual slavery during conflict; forced sterilization; forced abortion; violence by the police and authoritative personnel; stoning and flogging. Many forms of VAW, such as trafficking in women and forced prostitution are often perpetrated by organized criminal networks.[19] Historically, there have been forms of organized WAV, such as the Witch trials in the early modern period or the sexual slavery of the comfort women.

According to the UN, "there is no region of the world, no country and no culture in which women's freedom from violence has been secured."[246] Several forms of violence are more prevalent in certain parts of the world, often in developing countries. For example, dowry violence and bride burning is associated with India, Bangladesh, and Nepal. Acid throwing is also associated with these countries, as well as in Southeast Asia, including Cambodia. Honor killing is associated with the Middle East and South Asia. Female genital mutilation is found mostly in Africa, and to a lesser extent in the Middle East and some other parts of Asia. Marriage by abduction is found in Ethiopia, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. Abuse related to payment of bride price (such as violence, trafficking, and forced marriage) is linked to parts of Sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania (also see Lobolo).[251][252]

Acts of violence against women are often not unique episodes, but are ongoing over time. More often than not, the violence is perpetrated by someone the woman knows, not by a stranger.[253]

The WHO, in its research on VAW, has analyzed and categorized the different forms of VAW occurring through all stages of life from before birth to old age.[34]

In recent years, there has been a trend of approaching VAW at an international level through means such as conventions or, in the European Union, through directives (such as the directive against sexual harassment, and the directive against human trafficking).[254][255]

The Gender Equality Commission of the Council of Europe identifies nine forms of violence against women based on subject and context rather than life cycle or time period:[256][257]

- 'Violence within the family or domestic violence'

- 'Rape and sexual violence'

- 'Sexual harassment'

- 'Violence in institutional environments'

- 'Female genital mutilation'

- 'Forced marriages'

- 'Violence in conflict and post-conflict situations'

- 'Killings in the name of honour'

- 'Failure to respect freedom of choice with regard to reproduction'

By age groups

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a typology of violence against women based on their cultural life cycles.

| Phase | Type of violence |

| Pre-birth | Sex-selective abortion; effects of battering during pregnancy on birth outcomes |

| Infancy | Female infanticide; physical, sexual and psychological abuse |

| Girlhood | Child marriage; female genital mutilation; physical, sexual and psychological abuse; incest; child prostitution and pornography |

| Adolescence and adulthood | Dating and courtship violence (e.g. acid throwing and date rape); economically coerced sex (e.g. school girls having sex with "sugar daddies" in return for school fees); incest; sexual abuse in the workplace; rape; sexual harassment; forced prostitution and pornography; trafficking in women; partner violence; marital rape; dowry abuse and murders; partner homicide; psychological abuse; abuse of women with disabilities; forced pregnancy |

| Elderly | Forced "suicide" or homicide of widows for economic reasons; sexual, physical and psychological abuse[34] |

Significant progress towards the protection of women from violence has been made on international level as a product of collective effort of lobbying by many women's rights movements; international organizations to civil society groups. As a result, worldwide governments and international as well as civil society organizations actively work to combat violence against women through a variety of programs. Among the major achievements of the women's rights movements against violence on girls and women, the landmark accomplishments are the "Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women" that implies "political will towards addressing VAW " and the legal binding agreement, "the Convention on Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)".[258] In addition, the UN General Assembly resolution also designated 25 November as International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.[259]

A typology similar to the WHO's from an article on violence against women published in the academic journal The Lancet shows the different types of violence perpetrated against women according to what time period in a women's life the violence takes place.[253] However, it also classifies the types of violence according to the perpetrator. One important point to note is that more of the types of violence inflicted on women are perpetrated by someone the woman knows, either a family member or intimate partner, rather than a stranger.

Indigenous people

Indigenous women around the world are often targets of sexual assault or physical violence. Many indigenous communities are rural, with few resources and little help from the government or non-state actors. These groups also often have strained relationships with law enforcement, making prosecution difficult. Many indigenous societies also find themselves at the center of land disputes between nations and ethnic groups, often resulting in these communities bearing the brunt of national and ethnic conflicts.[260]

Violence against indigenous women is often perpetrated by the state, such as in Peru, in the 1990s. President Alberto Fujimori (in office from 1990 to 2000) has been accused of genocide and crimes against humanity as a result of a forced sterilization program put in place by his administration.[261] During his presidency, Fujimori put in place a program of forced sterilizations against indigenous people (mainly the Quechuas and the Aymaras), in the name of a "public health plan", presented 28 July 1995.

Bolivia has the highest rate of domestic violence in Latin America.[262][263] Indigenous women self-report physical or sexual violence from a current or former partner at rates of twenty-nine percent, in comparison to the national average of twenty four percent.[264] Bolivia is largely indigenous in its ethnic demographics, and Quechua, Aymara, and Guarani women have been monumental in the nation's fight against violence against women.[265][266]

Guatemalan indigenous women have also faced extensive violence. Throughout over three decades of conflict, Maya women and girls have continued to be targeted. The Commission for Historical Clarification found that 88% of women affected by state-sponsored rape and sexual violence against women were indigenous.

The concept of white dominion over indigenous women's bodies has been rooted in American history since the beginning of colonization. The theory of manifest destiny went beyond simple land extension and into the belief that European settlers had the right to exploit Native women's bodies as a method of taming and "humanizing" them.[267][268]

Canada has an extensive problem with violence against indigenous women, by both indigenous men and non-aboriginals. "[I]t has been consistently found that Aboriginal women have a higher likelihood of being victimized compared to the rest of the female population."[269] While Canadian national averages of violence against women are falling, they have remained the same for aboriginal communities throughout the years. The history of residential schools and economic inequality of indigenous Canadians has resulted in communities facing violence, unemployment, drug use, alcoholism, political corruption, and high rates of suicide.[267] In addition, there has been clear and admitted racism towards indigenous people by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, making victims less likely to report cases of domestic violence.[270]

Many of the issues facing indigenous women in Canada have been addressed via the Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women (MMIW) initiatives. Thousands of Native Canadian women have gone missing or been killed in the past 30 years, with little representation or attention from the government. Efforts to make the Canadian public aware of these women's disappearances have mostly been led by Aboriginal communities, who often reached across provinces to support one another. In 2015, prime minister Stephen Harper commented that the issue of murdered and missing indigenous women was "not high on our radar",[271] prompting outrage in already frustrated indigenous communities. A few months later, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau launched an official inquiry into the Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women.

In the United States, Native American women are more than twice as likely to experience violence than any other demographic.[267] One in three Native women is sexually assaulted during her life, and 67% of these assaults are perpetrated by non-Natives,[272][267][273] with Native Americans constituting 0.7% of U.S. population in 2015.[274] The disproportionate rate of assault to indigenous women is due to a variety of causes, including but not limited to the historical legal inability of tribes to prosecute on their own on the reservation. The federal Violence Against Women Act was reauthorized in 2013, which for the first time gave tribes jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute felony domestic violence offenses involving Native American and non-Native offenders on the reservation,[275] as 26% of Natives live on reservations.[276][277] In 2019 the Democrat House passed H.R. 1585 (Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019) by a vote of 263–158, which increases tribes' prosecution rights much further. However, in the Republican Senate its progress has stalled.[278]

Immigrants and refugees