Heinkel He 162

The Heinkel He 162 Volksjäger (German, "People's Fighter") was a German single-engine, jet-powered fighter aircraft fielded by the Luftwaffe in World War II. Developed under the Emergency Fighter Program, it was designed and built quickly and made primarily of wood as metals were in very short supply and prioritised for other aircraft. Volksjäger was the Reich Air Ministry's official name for the government design program competition won by the He 162 design. Other names given to the plane include Salamander, which was the codename of its wing-construction program, and Spatz ("Sparrow"), which was the name given to the plane by the Heinkel aviation firm.[1]

| He 162 | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| He 162A, WkNr. 120230, during post-war trials in the USA | |

| Role | Jet fighter |

| National origin | Germany |

| Manufacturer | Heinkel |

| First flight | 6 December 1944 |

| Introduction | January 1945 |

| Retired | May 1945 |

| Primary user | Luftwaffe |

| Produced | 1945 |

| Number built | About 320 |

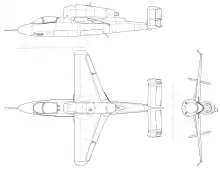

The aircraft was notable for its small size; although almost the same length as a Bf 109, its wing was much shorter at 7.2 metres (24 ft) vs. 9.9 metres (32 ft) for the 109. Most distinctive was its top-mounted engine, which combined with the aircraft's ground-hugging landing gear allowed the engine to be easily accessed for maintenance. This made bailing out of the aircraft without hitting the engine difficult, and the He 162 is thus also notable as the first single-engine aircraft to mount an ejection seat in an operational setting. The small size left little room for fuel, which combined with the inefficient engine resulted in very low endurance on the order of 20 minutes, and it only had room to mount two autocannons, making it quite underarmed for the era.

A series of fatal accidents during testing required a series of refinements that delayed the program, but the aircraft eventually emerged in January 1945 as an excellent light fighter. Although production lines were set up and deliveries began, the state of Germany by that time made the effort pointless. Of just less than 1,000 examples on the assembly lines, only about 120 were delivered to the airfields and most of those never flew, usually due to shortages of parts, fuel, and pilots. Small numbers were used in development squadrons and these ultimately saw combat in a few cases during April 1945, yet the He 162 also proved to be quite dangerous to its own pilots as its tiny fuel load led to a number of aircraft crashing off field, while additional losses were attributed to structural failure.

Production was still ongoing when the war ended in May 1945. Numerous aircraft were captured by the Allied forces along with ample supplies of parts from the production lines. Eric Brown flew one just after the war and considered it a first-rate aircraft with few vices. Several He 162s have been preserved in museum collections around the world.

Development

State of the Luftwaffe fighter arm

Through 1943 the U.S. 8th Air Force and German Luftwaffe entered a period of rapid evolution as both forces attempted to gain an advantage. Having lost too many fighters to the bombers' defensive guns, the Germans invested in a series of heavy weapons that allowed them to attack from outside the American guns' effective range. The addition of heavy cannons like the 30mm calibre MK 108, and even heavier Bordkanone autoloading weapons in 37mm and 50mm calibres on their Zerstörer heavy fighters, and the spring-1943 adoption of the Werfer-Granate 21 unguided rockets, gave the German single and twin-engined defensive fighters a degree of firepower never seen previously by Allied fliers. Meanwhile, the single-engine aircraft like specially equipped Fw 190As added armor to protect their pilots from Allied bombers' defensive fire, allowing them to approach to distances where their heavy weapons could be used with some chance of hitting the bombers. All of this added greatly to the weight being carried by both the single and twin-engine fighters, seriously affecting their performance.[2][3]

When the 8th Air Force re-opened its bombing campaign in early 1944 with the Big Week offensive, the bombers returned to the skies with the long-range P-51 Mustang in escort. Unencumbered with the heavy weapons needed to down a bomber, the Mustangs (and longer-ranged versions of other aircraft) were able to fend off the Luftwaffe with relative ease. The Luftwaffe responded by changing tactics, forming in front of the bombers and making a single pass through the formations, giving the defense little time to react. The 8th Air Force responded with a change of its own; after Major General Jimmy Doolittle ordered the fighters to enter German airspace far ahead of the bomber formations and roam freely over Germany to hit the Luftwaffe's defensive fighters wherever they could be found.[4]

This change in tactics resulted in a sudden increase in the rate of irreplaceable losses to the Luftwaffe day fighter force, as their heavily laden aircraft were "bounced" long before reaching the bombers.[5] Within weeks, many of their aces were dead, along with hundreds of other pilots, and the training program could not replace their casualties quickly enough. The Luftwaffe put up little fight during the summer of 1944, allowing the Allied landings in France to go almost unopposed from the air. With few planes coming up to fight, Allied fighters were let loose on the German airbases, railways and truck traffic. Logistics soon became a serious problem for the Luftwaffe, as maintaining aircraft in fighting condition became almost impossible. Getting enough fuel was even more difficult because of a devastating campaign against German petroleum industry targets.[6][7]

Origins

Addressing this posed a considerable problem for the Luftwaffe. Two camps quickly developed, both demanding the immediate introduction of large numbers of jet fighter aircraft. One group, led by General Adolf Galland, the Inspector of Fighters, reasoned that superior numbers had to be countered with superior technology, and demanded that all possible effort be put into increasing the production of the Messerschmitt Me 262 in its A-1a fighter version, even if that meant reducing production of other aircraft in the meantime.[8]

The second group pointed out that this would likely do little to address the problem; the Me 262 had notoriously unreliable powerplants and landing gear, and the existing logistics problems would mean there would merely be more of them on the ground waiting for parts that would never arrive, or for fuel that was not available.[9] Instead, they suggested that a new design be built – one so inexpensive that if a machine was damaged or worn out, it could simply be discarded and replaced with a fresh plane straight off the assembly line.[10] Thus was born the concept of the "throwaway fighter".

Galland and several other Luftwaffe senior officers expressed their vehement opposition to the light fighter concept,[8][11] while Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring and Armaments Minister Albert Speer fully supported the idea. Göring and Speer got their way; accordingly, a contract tender to supply a single-engine jet fighter that was suited for cheap and rapid mass production was established under the name Volksjäger ("People's Fighter").

Volksjäger

The official RLM Volksjäger design competition parameters specified a single-seat fighter, powered by a single BMW 003,[12][13] a slightly lower-thrust engine not in demand for either the Me 262 or the Ar 234, already in service.[14] The main structure of the Volksjäger competing airframe designs would use cheap and unsophisticated parts made of wood and other non-strategic materials and, more importantly, could be assembled by semi- and non-skilled labor, including slave labor.[15][16]

The specification stipulated various performance requirements, including a maximum weight of 2,000 kg (4,400 lb),[12] a maximum speed of 750 km/h (470 mph) at sea level, an operational endurance at least a half hour, while the takeoff distance was to be no greater than 500 m (1,640 ft).[14] Provisions for armour plating in areas such as the fuel tanks and around the pilot were also to be made, however, manufacturers were also asked to provide detail on the aircraft's performance both with and without armour installed. The armament was specified as either a pair of 20 mm (0.79 in) MG 151/20 cannons with 100 rounds each, or two 30 mm (1.2 in) MK 108 cannons with 50 rounds each.[17]

Furthermore, the Volksjäger needed to be easy to fly.[10] Some officials, such as Artur Axmann and Karl Saur, suggested even glider or student pilots should be able to fly the jet effectively in combat and, had the Volksjäger achieved widespread use, this would have been a likely occurrence.[18] After the war, Ernst Heinkel would say, "[The] unrealistic notion that this plane should be a 'people's fighter,' in which the Hitler Youth, after a short training regimen with clipped-wing two-seater gliders like the DFS Stummel-Habicht, could fly for the defense of Germany, displayed the unbalanced fanaticism of those days."[19][20] The clipped-wingspan DFS Habicht models had varying wingspans of both 8 m (26 ft 3 in) or 6 m (19 ft 8 in), and were used to prepare more experienced Luftwaffe pilots for the dangerous Me 163B Komet rocket fighter – the same sort of training approach would also be used for the Hitler Youth aviators chosen to fly the Volksjäger.[21]

On 8 September 1944, the requirement was issued to industry;[15][22] bidders were required to submit their basic designs within ten days while quantity production of the aircraft was to commence by 1 January 1945.[23] Because the winner of the new lightweight fighter design competition would be building huge numbers of the planes, nearly every German aircraft manufacturer expressed interest in the project, such as Blohm & Voss, and Focke-Wulf, whose Focke-Wulf Volksjäger 1 design contender, likewise meant for BMW 003 turbojet power bore a resemblance to their slightly later Ta 183 Huckebein jet fighter design. However, Heinkel had already been working on a series of "paper projects" for light single-engine fighters over the last year under the designation P.1073, with most design work being completed by Professor Benz, and had gone so far as to build and test several models and conduct some wind tunnel testing.[24]

As Heinkel had a head start on its design, some officials believed that the outcome was a largely foregone conclusion.[17] Nevertheless, many companies opted to produce responses; some of these competing designs were technically superior (in particular to the Blohm & Voss P 211 proposal). Messerschmitt did not submit any design, the company's founder, Willy Messerschmitt, dismissed the Volksjäger concept to be a delusional failure.[25] During October 1944, the competition's results were announced, only three weeks following the requirement being issued; to little surprise, Heinkel's submission was selected for production.[26] In order to confuse Allied intelligence, the RLM chose to reuse the 8-162 airframe designation (formerly that of a Messerschmitt fast bomber);[27] Heinkel had reportedly requested another designation, He 500, for the aircraft.[28][29]

Design

Heinkel had carried out some design work of a new twin-engine fighter with one engine placed on top of the aircraft and another under the nose, the highest point on the bottom of the fuselage. For the single-engine development, he removed the lower engine and repositioned the remaining upper engine just aft of the cockpit and centered directly over the wing's center section.[30] This arrangement simplified the overall balance of the aircraft, while also placing the engine in a convenient point for removal as it could be removed upward with a small crane.[31] The need for a crane to be present at every airfield that the aircraft would operate from was a point of contention of the aircraft from Heinkel's rivals.[32]

One consequence of the aircraft's basic configuration was that the jet exhaust would pass directly over the upper rear fuselage and the tail area. For this reason, the tail was constructed with two small vertical stabilizers positioned to either side of the exhaust's path, and the horizontal elevator mounted below it.[33] The horizontal section had considerable dihedral at 14º, raising the vertical stabilizers inline with the wing.[34]

The aircraft's relatively compact wing was mounted relatively high on the fuselage and was attached using four bolts.[12][33] The leading edge was straight while the trailing edge had a significant forward sweep. It was not possible to remove the wing without first removing the engine, an arrangement that would have hindered routine maintenance of the aircraft.[32] The combination of the engine being directly above the pilot and the wings on either side would make a conventional bailout very risky, so the aircraft was designed from the start to feature an ejection seat akin to the one used in the Heinkel He 219 night fighter.

The main landing gear retracted into the fuselage below the wing and were of the tricycle layout.[33] Heinkel had significant previous experience with this layout on earlier designs including the Heinkel He 280,[35][36] however, this was the first of their designs to use this layout from the start. A small window in the lower cockpit between the rudder pedals allowed the pilot to visually check whether the gear was down.[37][38][39] Partly due to the late-war period it was designed within, some of the He 162's landing gear components were "recycled" existing landing gear components from a contemporary German military aircraft to save development time: the main landing gear's oleo struts and wheel/brake units came from the Messerschmitt Bf 109K, as well as the double-acting hydraulic cylinders, one per side, used to raise and lower each maingear leg.[40]

Prototypes

The He 162 V1 first prototype flew within an astoundingly short period of time: the design was chosen on 25 September 1944 and first flew on 6 December,[31][41] less than 90 days later. This was despite the fact that the factory in Wuppertal making Tego film plywood glue — used in a substantial number of late-war German aviation designs whose airframes and/or major airframe components were meant to be constructed mostly from wood — had been bombed by the Royal Air Force and a replacement had to be quickly substituted, without realizing that the replacement adhesive was highly acidic and would disintegrate the wooden parts it was intended to be fastening.[42]

The first flight of the He 162 V1, by Flugkapitän Gotthold Peter – the first German jet fighter aircraft design to be jet-powered from its maiden flight onward – was fairly successful, but during a high-speed run at 840 km/h (520 mph), the highly acidic replacement glue attaching the nose gear strut door failed and the pilot was forced to land. Other problems were noted as well, notably a pitch instability and problems with sideslip due to the rudder design.[12][43] None were considered important enough to hold up the production schedule for even a day. On a second flight on 10 December, again with Peter at the controls, in front of various Nazi officials, the glue again caused a structural failure. This allowed the aileron to separate from the wing, causing the plane to roll over and crash, killing Peter.[31][44]

An investigation into the failure revealed that the wing structure had to be strengthened and some redesign was needed, as the glue bonding required for the wood parts was in many cases defective.[31][42] However, the schedule was so tight that testing was forced to continue with the current design. Speeds were limited to 500 km/h (310 mph) when the second prototype flew on 22 December. This time, the stability problems proved to be more serious, and were found to be related to phenomenon known as Dutch roll.[45] While this tendency could be resolved by reducing the dihedral, however, as the He 162 was supposed to enter production within weeks, there was no time to implement major design changes. Instead, a number of small changes were made, such as the addition of lead ballast in the nose to move the centre of gravity towards the front of the aircraft while the tail surfaces were also slightly increased in size. Despite these measures, some figures, such as Alexander Lippisch, declared the flying characteristics of the He 162 to be unsuitable for inexperienced pilots.[46]

The third and fourth prototypes, which used an "M" for "Muster" (model) number instead of "V" for "Versuchs" (experimental) number, as the He 162 M3 and M4, after being fitted with the strengthened wings, flew in mid-January 1945.[47][48] These versions also included – as possibly the pioneering example of their use on a production-line, military jet aircraft – small, anhedraled aluminium "drooped" wingtips, reportedly designed by Alexander Lippisch and known in German as Lippisch-Ohren ("Lippisch Ears"), in an attempt to cure the stability problems via effectively "decreasing" the main wing panels' marked three degree dihedral angle.[49] Both prototypes were equipped with two 30 mm (1.18 in) MK 108 cannons in the He 162 A-1 anti-bomber variant; in testing, the recoil from these guns proved to be too much for the lightweight fuselage to handle, and plans for production turned to the A-2 fighter with two 20 mm MG 151/20 cannons instead while a redesign for added strength started as the A-3. The shift to 20 mm guns was also undertaken because the smaller-calibre weapons would allow a much greater amount of ammunition to be carried.

The He 162 was originally built with the intention of being flown by the Hitler Youth, as the Luftwaffe was fast running out of pilots. However, the aircraft's complexity required more experienced pilots. Both a standard-fuselage length, unarmed BMW 003E-powered two-seat version (with the rear pilot's seat planned to have a ventral access hatch to access the cockpit) and an unpowered two-seat glider version, designated the He 162S (Schulen), were developed for training purposes.[50] Only a small number were built, and even fewer delivered to the sole He 162 Hitler Youth training unit to be activated (in March 1945) at an airbase at Sagan. The unit was in the process of formation when the war ended, and did not begin any training; it is doubtful that more than one or two He 162S gliders ever took to the air.

Various changes had raised the weight over the original 2,000 kg (4,410 lb) limit, but even at 2,800 kg (6,170 lb), the He 162 was still among the fastest aircraft in the air with a maximum airspeed of 790 km/h (427 kn; 491 mph) at sea level and 839 km/h (453 kn; 521 mph) at 6,000 m (20,000 ft),[51] but could reach 890 km/h (481 kn; 553 mph) at sea level and 905 km/h (489 kn; 562 mph) at 6,000 m (20,000 ft) using short burst extra thrust.[52] The short flight duration of barely 30 minutes was due to only having a single 695-litre (183 US gallon) capacity flexible-bladder fuel tank in the fuselage directly under the engine's intake.[53] The original Baubeschreibung document submittal for the He 162 dated mid-October 1944 showed a pair of fuel tanks for the original version of the Spatz's airframe as-designed: a single, smaller capacity 640 litre (169 US gal) fuselage main tank in approximately the same location as the later 695 litre tank was placed, with an additional wing centre-section tank just above and behind it, never produced for the production run, of some 325 litres (86 US gal) feeding by gravity into the main fuselage tank.[54] The A-2 version, in some examples (as the one flown by Royal Navy test pilot Captain Eric Brown postwar) had an emplacement of a pair of "impregnated" 180 litre (47.5 US gal) wing tanks, one built into each inner wing panel, within the first four wing ribs out from the root and between the spars, that fed into the main 695 litre fuselage tank in a similar manner to what the earlier 325 litre center-section tank had been proposed to do; but were themselves ungauged, their exhaustion of fuel only marked when the main fuel gauge began to fall during flight.[55] The production He 162A-2 was armed with a pair of 20mm MG 151/20 cannon.[51][56]

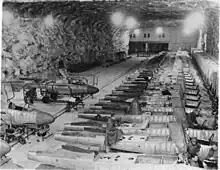

Multiple facilities were engaged in the production of the He 162, including the assembly lines in Salzburg, the Hinterbrühl, and the Mittelwerk.[51][57] By April 1945, it had been anticipated that output would reach 1,000 aircraft per month, which was double the rate achieved when the Mittelwerk plant commenced deliveries.[51] Furthermore, the Air Ministry expected that production were rise even beyond this figure in order to produce sufficient fighter coverage.[58][59]

Operational history

During January 1945, the Luftwaffe formed an Erprobungskommando 162 ("Test Unit 162") evaluation group to which the first 46 aircraft were delivered. The group was based at the Luftwaffe main test center, or Erprobungsstelle at Rechlin.

In February, deliveries of the He 162 commenced to its first operational unit, I./JG 1 (1st Group of Jagdgeschwader 1 Oesau — "1st Fighter Wing"), which had previously flown the Focke-Wulf Fw 190A. I./JG 1 was transferred to Parchim, which, at the time, was also a base for the Me 262-equipped Jagdgeschwader 7, some 80 km south-southwest of the Heinkel factory's coastal airfield at "Marienehe" (today known as Rostock-Schmarl, northwest of the Rostock city centre), where the pilots could pick up their new jets and start intensive training beginning in March 1945. This was all happening simultaneously with unrelenting Allied air attacks on the transportation network, aircraft production facilities and petroleum, oil, and lubrication (POL) product-making installations of the Third Reich – these had now begun to also target the Luftwaffe's jet and rocket fighter bases as well. On 6 April, the USAAF bombed the field at Parchim with 134 B-17 Flying Fortresses, inflicting serious losses and damage to the infrastructure.[60] Two days later, I./JG 1 moved to an airfield at nearby Ludwigslust and, less than a week later, moved again to an airfield at Leck, near the Danish border. On 8 April, II./JG 1 moved to Heinkel's aforementioned Rostock northwestern coastal suburban factory airfield and started converting from Fw 190As to He 162s. III./JG 1 was also scheduled to convert to the He 162, but the Gruppe disbanded on 24 April and its personnel were used to fill in the vacancies in other units.

The He 162 first saw combat in mid-April 1945. On 19 April, Feldwebel Günther Kirchner shot down a Royal Air Force fighter and, although the victory was credited to a flak unit, the British pilot confirmed during interrogation that he had been downed by an He 162.[61][62] The Heinkel and its pilot were both lost that same day as well, having been shot down over Husum by Flying Officer Geoffrey Walkington,[63][64] piloting an RAF Hawker Tempest. Though still in training, I./JG 1 began to score kills in mid-April, but went on to lose 13 He 162s and 10 pilots. Ten of the aircraft were operational losses, caused by flameouts and sporadic structural failures. Only two of the 13 aircraft were actually shot down. The He 162's 30-minute fuel capacity also caused problems, as at least two of JG 1's pilots were killed attempting emergency deadstick landings after exhausting their fuel.

During its exceedingly brief operational service career, the He 162's cartridge-type ejector seat was employed under combat conditions by JG 1's pilots at least four times. Fw. Günther Kirchner was the first to attempt an ejection on April 19, but he was too low and was killed when his parachute failed to open.[65][66] The second recorded use was by Lt Rudolf Schmidt on April 20, with Fw. Erwin Steeb ejecting from his He 162 the following day. Finally, Hptm. Paul-Heinrich Dähne attempted to eject from his aircraft on April 24, but was killed when the cockpit canopy failed to detach.

In the last days of April, as the Soviet troops approached, II./JG 1 evacuated from Marienehe and on 2 May joined the I./JG 1 at Leck. On 3 May, all of JG 1's surviving He 162s were restructured into two groups, I. Einsatz ("Combat") and II. Sammel ("Collection"). All JG 1's aircraft were grounded on 5 May, when General Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg signed the surrender of all German armed forces in the Netherlands, Northwest Germany and Denmark. On 6 May, when the British reached their airfields, JG 1 turned their He 162s over to the Allies.[67] Numerous aircraft were shipped to the U.S., Britain, France, and the Soviet Union for further evaluation.[68][69]

Erprobungskommando 162 fighters, which had been passed on to JV 44, an elite jet unit under Adolf Galland a few weeks earlier, were all destroyed by their crews to keep them from falling into Allied hands. Heinkel did not resort to such measures, the company's engineers supplied the Americans with detailed designs for the He 162.[70] By the time of Germany's unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945, 120 He 162s had been delivered while a further 200 had been completed and were awaiting collection or flight-testing; an additional 600 or so aircraft were in various stages of production,

The difficulties experienced by the He 162 are believed to have been primarily a result of its rush into production, rather than any inherent design flaw.[71] One experienced Luftwaffe pilot who flew the He 162 called it a "first-class combat aircraft." Test pilot Eric Brown of the Fleet Air Arm, who flew a record 486 different types of aircraft, said the He 162 had "the lightest and most effective aerodynamically balanced controls" he had experienced.[72] Brown had been warned to treat the rudder with suspicion due to a number of in-flight failures. This warning was passed on by Brown to RAF pilot Flt Lt R A Marks, but was apparently not heeded. On 9 November 1945, during a demonstration flight from RAE Farnborough, one of the fin and rudder assemblies broke off at the start of a low-level roll causing the aircraft to crash into Oudenarde Barracks, Aldershot, killing Marks and a soldier on the ground.[73]

He 162 Mistel

The Mistel series of fighter/powered bomb composite ground-attack aircraft pre-dated the He 162 by over two years, and the Mistel 5 project study in early 1945 proposed the mating of an He 162A-2 to the Arado E.377A flying bomb.[31][74] The fighter would sit atop the bomb, which would itself be equipped with two underwing-mounted BMW 003 turbojets. This ungainly combination would take off on a sprung trolley fitted with tandem wheels on each side for the "main gear" equivalent, derived from that used on the first eight Arado Ar 234 prototypes, with all three jets running. Immediately after take-off, the trolley would be jettisoned, and the Mistel would then fly to within strike range of the designated target. Upon reaching this point, the bomb would be aimed squarely at the target and then released, with the jet turning back for home. The Mistel 5 remained a "paper project", as the Arado bomb never progressed beyond the blueprint stage.

Variants

- He 162 A-0 — first ten pre-production aircraft.

- He 162 A-1 — armed with two 30 mm (1.18 in) MK 108 cannons with 50 rounds per gun.

- He 162 A-2 — armed with two 20 mm MG 151/20 cannons with 120 rounds per gun.

- He 162 A-3 — proposed upgrade with reinforced nose mounting twin 30 mm MK 108 cannons.

- He 162 A-8 — proposed upgrade with the more powerful Jumo 004D-4 engine of 10.3 kN (2,300 lbf) top thrust levels. Muster (model) prototype airframes M11 and M12's testing revealed a top speed of 885 km/h (550 mph) at sea level at normal thrust and 960 km/h (597 mph) with maximum thrust,[75] close to the Me 163B rocket fighter's top velocity figures.

- He 162 B-1 — a proposed follow on planned for 1946, meant to use the Heinkel firm's own, more powerful 12 kN (2,700 lb) thrust Heinkel HeS 011A turbojet, a stretched fuselage to provide more fuel and endurance as well as increased wingspan, with reduced dihedral which allowed the omission of the anhedral wingtip devices. To be armed with twin 30 mm (1.18 in) MK 108s.

- The He 162B airframe was also used as the basis for the Miniature Fighter Project design competition powered by one or two "square-intake" Argus As 044 pulsejet engines. The pulsejet, however didn't provide enough thrust for takeoff and neither Heinkel nor the OKL showed much enthusiasm for the project.[76]

- He 162C — proposed upgrade featuring the B-series fuselage, Heinkel HeS 011A engine, swept-back, anhedraled outer wing panels forming a gull wing, a new V-tail stabilizing surface assembly, and upward-aimed twin 30 mm (1.18 in) MK 108s as a Schräge Musik weapons fitment, located right behind the cockpit.

- He 162D — proposed upgrade with a configuration similar to C-series but a dihedraled forward-swept wing.[62][77]

- He 162E — He 162A fitted with the BMW 003R mixed power plant, a BMW 003A turbojet with an integrated BMW 718 liquid-fuel rocket engine — mounted just above the exhaust orifice of the turbojet — for boost power. At least one prototype was built and flight-tested for a short time.

- He 162S — two-seat training glider.

Operators

- French Air Force (Test aircraft)

Aircraft on display

- An He 162 A-2 (Werknummer 120227) of JG 1 is on display at the Royal Air Force Museum London, Hendon, London, UK.[78]

- An He 162 A-2 (Werknummer 120077) is displayed at the Planes of Fame Museum on static display in Chino, California, USA. This aircraft was captured by the British at Leck and sent to the United States in 1945 where it was given the designation FE-489 (Foreign Equipment 489) and later T-2-489.[79]

- An He 162 A-2 (Werknummer 120230), thought to have been flown by Oberst Herbert Ihlefeld of 1./JG 1, is currently owned by the American Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum, USA.[80] This He 162A, after being captured by the British at Leck and sent to the US on board HMS Reaper, an escort carrier, is currently fitted with the tail unit from Werknummer 120222.

- An He 162 A-2 (Werknummer 120086) is on display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.[81]

- An He 176A-2[82] (Werknummer 120076) is displayed at the Deutsches Technikmuseum Berlin.[83]

- An He 162 A-1 (Werknummer 120235) Currently under restoration, is in Hangar 5 of The Imperial War Museum Duxford, UK.[84]

- An He 162 A-2 (Werknummer 120015) formerly of III./JG1, is currently under restoration at the Musée de l'Air et de l'Espace near Paris, France, with a fully restored and operable retracting landing gear.[37]

- An He 162 is most likely in storage at the US Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum (Werk Nummer 120222, Air Force number T-2-504).[85]

Wk. Nr. 120227, RAF Museum, London

Wk. Nr. 120227, RAF Museum, London Wk. Nr. 120235, Imperial War Museum, London (now moved to Duxford)

Wk. Nr. 120235, Imperial War Museum, London (now moved to Duxford) Wk. Nr. 120086, Canada Aviation and Space Museum, Ottawa

Wk. Nr. 120086, Canada Aviation and Space Museum, Ottawa

Reproduction

- He 162, produced by George Lucas (Nunda, NY) displayed at National Warplane Museum, Geneseo NY (www.nationalwarplanemuseum.com)

Specifications (He 162A)

Data from Hitler's Luftwaffe.[53]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 9.05 m (29 ft 8 in)

- Wingspan: 7.2 m (23 ft 7 in)

- Height: 2.6 m (8 ft 6 in)

- Wing area: 11.16 m2 (120.1 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 1,660 kg (3,660 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 2,800 kg (6,173 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 695 L (184 US gal; 153 imp gal)

- Powerplant: 1 × BMW 109-003E-1 or BMW 109-003E-2 turbojet engine, 7.85 kN (1,760 lbf) thrust

Performance

- 840 km/h (520 mph; 450 kn) at 6,000 m (20,000 ft) (normal thrust)

- 890 km/h (550 mph; 480 kn) at sea level (emergency boosted thrust)

- 905 km/h (562 mph; 489 kn) at 6,000 m (20,000 ft) (emergency boosted thrust)

- Range: 975 km (606 mi, 526 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 12,000 m (39,000 ft)

- Rate of climb: 23.42 m/s (4,610 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 252 kg/m2 (52 lb/sq ft)

- Thrust/weight: 0.35 (normal thrust)

- 0.41 (emergency boosted thrust)

Armament

- Guns: 2 × 20 mm (0.787 in) MG 151/20 autocannon with 120 rpg (He 162 A-2) or 2 × 30 mm (1.181 in) MK 108 cannon with 50 rpg (He 162 A-0, A-1)

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

Citations

- "Heinkel He 162 A-2 Spatz (Sparrow)". airandspace.si.edu. Smithsonian Institution National Air & Space Museum. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

Pilots mastered some of the Spatz's nasty habits but the jet would always be a difficult, even dangerous, aircraft to fly, even for experienced pilots...the He 162 has often been erroneously referred to as the Salmander. The term is a codename for the wing structure, not the aircraft.

- Weal 1996, p. 78.

- Forsyth 2009, pp. 58–59.

- McFarland and Newton 1991, .

- Hess 1994, pp. 77–78.

- Miller 2006, p. 320.

- Williamson, Charles C.; Hughes, R. D.; Cabell, C. P.; Nazarro, J. J.; Bender, F. P.; Crigglesworth, W. J. (5 March 1944). Plan for Completion of Combined Bomber Offensive. Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library: Smith, Walter Bedell: Collection of World War II Documents, 1941–1945; Box No.: 48 (Report). HQ, U.S.S.T.A.F.

- Dorr 2013, p. 153.

- Forsyth 2016, p. 8.

- Forsyth 2016, p. 7.

- Uziel 2011, pp. 240–243.

- Christopher 2013, p. 145.

- LePage 2009, p. 38.

- Forsyth 2016, pp. 8-9.

- LePage 2009, p. 244.

- Dorr 2013, p. 152.

- Forsyth 2016, p. 10.

- Forsyth 2016, pp. 17-18.

- Excerpt from Lucas Arts' "Secret Weapons of Luftwaffe" CD-ROM's Text Manual.

- Heath 2022, p. 223.

- Forsyth 2016, pp. 7-8.

- Dorr 2013, p. 151.

- Forsyth 2016, p. 9.

- Forsyth 2016, pp. 9-10.

- Forsyth 2016, p. 11.

- Forsyth 2016, p. 15.

- Sharp 2020b, p. 16.

- Sharp 2020b, p. 178.

- Forsyth 2016, p. 22.

- Sharp 2020b, pp. 177–178.

- Ford 2013, p. 224.

- Forsyth 2016, p. 14.

- Dorr 2013, p. 150.

- "Baubeschreibung des einmotorigen Jagdeinsitzers, Baumuster 162, mit TL-Triebwerk BMW 003 E-1 (in German)" (PDF). deutsche-luftwaffe.de. Heinkel Flugzeugwerke. 15 October 1944. p. 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Christopher 2013, p. 58.

- Sharp 2020b, p. 72.

- Heinkel 162 (He162) landing gear test (YouTube) (YouTube). Le Bourget, Paris, France: memorialflight. 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- Animation of He 162 nosegear retraction cycle

- Animation of He 162 maingear retraction cycle

- Sengfelder, Günther (1993). German Aircraft Landing Gear. Atglen, PA USA: Schiffer Publishing. pp. 136–137. ISBN 0-88740-470-7.

The He 162's landing gear consisted partly of elements taken from other designs. The main landing gear legs and wheels were from the Bf 109K. The hydraulic jack used to raise and lower the landing gear was also taken from the Bf 109.

- Forsyth 2016, pp. 24-25.

- Dorr 2013, p. 156.

- Forsyth 2016, pp. 25-29.

- Sharp 2020b, p. 18.

- Sharp 2020b, p. 155.

- Sharp 2020b, p. 311.

- Sharp 2020b, p. 11.

- Forsyth 2016, pp. 30-32.

- "Baubeschreibung des einmotorigen Jagdeinsitzers, Baumuster 162, mit TL-Triebwerk BMW 003 E-1 (in German)" (PDF). deutsche-luftwaffe.de. Heinkel Flugzeugwerke. 15 October 1944. p. 39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Forsyth 2016, p. 51.

- Christopher 2013, p. 146.

- Donald 1994, p. 119.

- Wood and Gunston 1977, pp. 194–195.

- "Baubeschreibung des einmotorigen Jagdeinsitzers, Baumuster 162, mit TL-Triebwerk BMW 003 E-1 (in German)" (PDF). deutsche-luftwaffe.de. Heinkel Flugzeugwerke. 15 October 1944. p. 43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Brown 2010, p. 137.

- Dorr 2013, p. 159.

- Dorr 2013, pp. 154-155.

- LePage 2009, p. 267.

- Sharp 2020b, p. 179.

- Forsyth 2016, p. 62.

- Mombeek 1992, p. 297.

- Dorr 2013, p. 160.

- Shores 2006, pp. 497–498.

- Thomas and Holmes 2016, pp. 60–61.

- Shores 2006, p. 498.

- Thomas and Holmes 2016, p. 60.

- Forsyth 2016, p. 81.

- Dorr 2013, p. 161.

- Forsyth 2016, pp. 6-7.

- Sharp 2020b, p. 148.

- LePage 2009, p. 266.

- Brown, Eric. "Mastering Heinkel's Minimus; Air Enthusiast, 2:6, June 1972.

- "Two Killed In Flying Accident". The Times. London, England. 10 November 1945. p. 2.

- LePage 2009, pp. 160-161.

- "History and Experiences of He-162" (PDF). wwiiaircraftperformance.org. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- The Heinkel He-162 Volksjaeger

- Sharp 2020b, p. 20.

- "Individual History: Heinkel He162A-2 W/NR.120227/AIR MIN 65/VN679/8472M, Museum Accession Number 1990/0697/A" (PDF). Royal Air Force Museum London. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- Forsyth & Creek 2008, p. 180

- "Heinkel He 162 A-2 Spatz (Sparrow)". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- "Heinkel He 162A-1 Volksjäger (120086) | Canada Aviation and Space Museum". ingeniumcanada.org. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- Sharp 2020a, p. 133

- "Deutsches Technikmuseum Berlin - Medieninfo: Heinkel He 162". Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- "Heinkel 162A-1 Salamander". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- Forsyth & Creek 2008, p. 181

Bibliography

- Brown, Eric (2010). Wings of the Luftwaffe: Flying Captured German Aircraft of World War II (Revised ed.). Manchester, UK: Hikoki Publications. ISBN 978-1-9021091-5-2.

- Christopher, John (2013). The Race for Hitler's X-Planes. Stroud, UK: History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6457-2.

- Donald, David (1994). Warplanes of the Luftwaffe. London, United Kingdom: Aerospace Publishing. ISBN 1-874023-56-5.

- Dorr, Robert F. (2013). Fighting Hitler's Jets. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-4398-2.

- Ford, Roger (2013). Germany's Secret Weapons of World War II. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books. ISBN 9781909160569.

- Forsyth, Robert; Creek, Eddie J (2008). Heinkel He 162 Volksjager: From Drawing Board to Destruction: The Volksjäger. Vol. 17. Hersham, United Kingdom: Classic Publications. ISBN 978-1-90653-700-5.

- Forsyth, Robert (2016). He 162 Volksjäger Units. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-47281-459-3.

- Forsyth, Robert (2009). Fw 190 Sturmböck vs B-17 Flying Fortress: Europe 1944–1945. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-941-6.

- Heath, Tim (2022). In Furious Skies: Flying with Hitler's Luftwaffe in the Second World War. Pen and Sword History. ISBN 978-1-5267-8526-8.

- Hess, William. N. (1994). B-17 Flying Fortress - Combat and Development History. Motor books. ISBN 0-87938-881-1.

- Lepage, Jean-Denis G. G. (2009). Aircraft of the Luftwaffe 1935–1945: An Illustrated History. Jefferson, North Carolina, US: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3937-9.

- McFarland, Stephen L.; Newton, Wesley Philips (1991). To Command the Sky: The Battle for Air Superiority Over Germany, 1942–1944. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098069-9.

- Miller, Donald L. (2006). Masters of the Air: America's Bomber Boys Who Fought the Air War Against Nazi Germany. New York, US: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-3544-0.

- Mombeek, Eric (1992). Defending the Reich- The History of Jagdgeschwader 1 'Oesau'. Norfolk, UK: JAC Publications. ISBN 0-9515737-1-3.

- Smith, J. Richard; Conway, William (1967). The Heinkel He 162 (Aircraft in Profile number 203). Leatherhead, United Kingdom: Profile Publications.

- Smith, J., Richard; Creek, Eddie J (1982). Jet Planes of the Third Reich. Boylston, Massachusetts, US: Monogram Aviation Publications. ISBN 0-914144-27-8.

- Sharp, Dan (2020a). Heinkel He 162. Secret Projects of the Luftwaffe. Vol. 1. Horncastle, UK: Tempest Books. ISBN 978-1-911658-24-5.

- Sharp, Dan (2020b). Secret Projects of the Luftwaffe - Vol 1 - Jet Fighters 1939 -1945. Tempest Books. ISBN 978-1-911658-80-1.

- Shores, Christopher (2006). 2nd Tactical Air Force. Volume III: From the Rhine to Victory: January to May 1945. Classic Publications. ISBN 1-90322-360-1.

- Thomas, Chris; Holmes, Tony (2016). Tempest Squadrons of the RAF. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-1454-8. OCLC 933722337.

- Uziel, Daniel (2011). Arming the Luftwaffe: The German Aviation Industry in World War II. Jefferson, US: McFarland. ISBN 9780786488797.

- Weal, John (1996). Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Aces of the Western Front. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-595-1.

- Wood, Tony; Gunston, Bill (1977). Hitler's Luftwaffe: A pictorial history and technical encyclopaedia of Hitler's air power in World War II. London, UK: Salamander Books. ISBN 0-86101-005-1.

Further reading

- Balous, Miroslav; Bílý, Miroslav (2004). Heinkel He 162 Spatz (Volksjäger) (in Czech and English). Prague, Czech Republic: MBI. ISBN 80-86524-06-X.

- Couderchon, Philippe (April 2006). "The Salamander in France Part 1". Aeroplane Magazine.

- Couderchon, Philippe (May 2006). "The Salamander in France Part". Aeroplane Magazine.

- Green, William (1970). Warplanes of the Third Reich (Fourth impression (1979) ed.). London, UK: Macdonald and Jane's Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0-356-02382-6.

- Griehl, Manfred (2007). The Luftwaffe Profile Series No.16: Heinkel He 162. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7643-1430-8.

- Griehl, Manfred (2007). Heinkel Strahlflugzeug He 162 "Volksjäger" — Entwicklung, Produktion und Einsatz (in German). Lemwerder, Germany: Stedinger Verlag. ISBN 978-3-927697-50-8.

- Hiller, Alfred (1984). Heinkel He 162 "Volksjäger" — Entwicklung, Produktion, Einsatz. Wien, Austria: Verlag Alfred Hiller.

- Ledwoch, Janusz (1998). He-162 Volksjager (Wydawnictwo Militaria 49). Warszawa, Poland: Wydawnictwo Militaria. ISBN 83-86209-68-2.

- Müller, Peter (2006). Heinkel He 162 "Volksjäger": Letzter Versuch der Luftwaffe (in German and English). Andelfingen, Germany: Müller History Facts. ISBN 3-9522968-0-5.

- Myhra, David (1999). X Planes of the Third Reich: Heinkel He 162. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 0-7643-0955-2.

- Nowarra, Heinz J. (1993). Heinkel He 162 "Volksjager". Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 0-88740-478-2.

- (Translation of: Der "Volksjäger" He 162 (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas Verlag. 1984. ISBN 3-7909-0216-0..)

- Peter-Michel, Wolfgang (2011). Flugerfahrungen mit der Heinkel He 162;— Testpiloten berichten (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: BOD-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8423-7048-7.

- Smith, J. Richard; Creek, Eddie J. (1986). Heinkel He 162 Volksjager (Monogram Close-Up 11). Acton, MA: Monogram Aviation Publications. ISBN 0-914144-11-1.

- Smith, J. Richard; Kay, Anthony (1972). German Aircraft of the Second World War (Third (1978) ed.). London, UK: Putnam & Company. ISBN 0-370-00024-2.

External links

- The NASM's Heinkel He 162A Spatz, to be restored Archived 2019-12-23 at the Wayback Machine

- The Heinkel He 162 Volksjäger at Greg Goebel's AIR VECTORS

- Heinkel He 162 Volksjäger in Detail Archived 2008-09-04 at the Wayback Machine

- (in German) Heinkel He 162 "Volksjäger"

- Heinkel 162 Ejection Seat

- He 162 "Salamander" Russian training film, 9 minutes (in Russian)

- Video of restored He 162A retractable landing gear testing for the Musee de l'Air's example

- The Memorial Flight's (France) restoration of He 162A WkNr. 120 015 Page

- December 2012 Interview with Harald Bauer, a surviving He 162A test pilot

- He 162 Mistel 5

- "Heinkel He 162 A-2 ("FE-504" c/n 120230) US Army Air Forces" photo of He 162 120230 with aircraft history

- "Heinkel He 162 A-2 ("T2-489" c/n 120077) US Army Air Forces "Nervenklau" Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine photo of He 162 120077 with aircraft history