West Florida

West Florida (Spanish: Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former Spanish Florida (East Florida formed the eastern part, with the Apalachicola River as the border), along with lands taken from French Louisiana; Pensacola became West Florida's capital. The colony included about two thirds of what is now the Florida Panhandle, as well as parts of the modern U.S. states of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama.

| West Florida | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territory of Great Britain (1763–1783), Spain (1783–1821). Areas disputed between Spain and United States from 1783–1795 and 1803–1821. | |||||||||||||||||

| 1763–1821 | |||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp)  | |||||||||||||||||

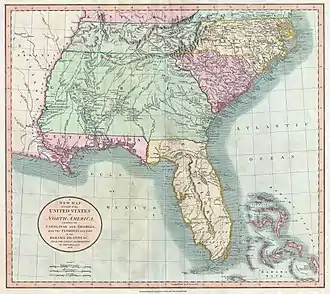

British West Florida in 1767 | |||||||||||||||||

Digital map of West Florida in 1767 | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Pensacola | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||||||

• 1763–1783 | 5 under Britain | ||||||||||||||||

• 1783–1821 | 10 under Spain | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

| February 10, 1763 | |||||||||||||||||

| November 25, 1783 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1795 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1800 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1810 | |||||||||||||||||

• Annexation by U.S. | 1810 | ||||||||||||||||

| February 22, 1821 | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Great Britain established West and East Florida in 1763 out of land acquired from France and Spain after the Seven Years' War. As the newly acquired territory was too large to govern from one administrative center, the British divided it into two new colonies separated by the Apalachicola River. British West Florida included the part of formerly Spanish Florida, which lay west of the Apalachicola, as well as parts of formerly French Louisiana; its government was based in Pensacola. West Florida thus encompassed all territory between the Mississippi and Apalachicola Rivers, with a northern boundary which shifted several times over the subsequent years.

Both West and East Florida remained loyal to the British crown during the American Revolution, and served as havens for Tories fleeing from the Thirteen Colonies. Spain invaded West Florida and captured Pensacola in 1781, and after the war Britain ceded both Floridas to Spain. However, the lack of defined boundaries led to a series of border disputes between Spanish West Florida and the fledgling United States known as the West Florida Controversy.

Because of disagreements with the Spanish government, American and English settlers between the Mississippi and Perdido rivers declared that area as the independent Republic of West Florida in 1810. No part of that short-lived republic lay within the borders of the modern U.S. state of Florida; rather, it comprised the Florida parishes of today's Louisiana. Within months it was annexed by the United States, which claimed the region as part of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. In 1819, the United States negotiated the purchase of the remainder of West Florida and all of East Florida in the Adams–Onís Treaty, and in 1822 both were merged into the Florida Territory.

Background

The area known as West Florida was originally claimed by Spain as part of La Florida, which included most of what is now the southeastern United States. Spain made several attempts to conquer and colonize the area, notably including Tristán de Luna's short-lived settlement in 1559, but it was not settled permanently until the 17th century, with the establishment of missions to the Apalachee. In 1698, the settlement of Pensacola was established to check French expansion into the area.

Beginning in the late 17th century, the French established settlements along the Gulf Coast and in the region as part of their colonial La Louisiane, including Mobile (1702) and Fort Toulouse (1717) in present-day Alabama[1]: 134 and Fort Maurepas (1699) in present-day coastal Mississippi. After years of contention between France and Spain, they agreed to use the Perdido River (the modern border between Florida and Alabama) as the boundary between French Louisiana and Spanish Florida.[1]: 122

Before 1762, France had owned and administered the land west of the Perdido River as part of La Louisiane. The secret Treaty of Fontainebleau, concluded in 1762 but not made public until 1764, had effectively ceded to Spain all of French Louisiana west of the Mississippi River, as well as the Isle of Orleans.

However, under the treaty that had concluded the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War) in 1763, Britain obtained immediate title to all of French La Louisiane east of the Mississippi River. This included the land between the Perdido and Mississippi. Spain also ceded to Great Britain its territory of La Florida, in exchange for Cuba, which the British had captured during the war. As a result, for the next two decades, the British controlled nearly all of the coast of the Gulf of Mexico east of the Mississippi River.[1]: 134 Most of the Spanish population left Florida at that time, and its colonial government records were relocated to Havana, Cuba.

Spain, meanwhile, failed to make good by occupancy its title to Louisiana until 1769, when it took formal possession. For six years, therefore, Louisiana as France possessed it, and as Spain received it,[2] included none of the territory between the Mississippi and Perdido rivers, as the title to that territory had passed immediately from France to Britain in 1763.[3]: 48

Colonial period

British era

Finding this new territory too large to govern as one unit, the British divided it into two new colonies, West Florida and East Florida, separated by the Apalachicola River, as set forth in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. East Florida consisted of most of the formerly Spanish Florida, and retained the old Spanish capital of St. Augustine. West Florida comprised the land between the Mississippi and Apalachicola Rivers, including land from what had been Spanish Florida and French Louisiana, with Pensacola designated as its capital. The northern boundary was arbitrarily set at the 31st parallel north.[1]: 134

Many English Americans and Scotch-Irish Americans moved to the territory at this time. The Governor of West Florida in November 1763 was George Johnstone; his lieutenant governor, Montfort Browne, was a major landowner in the province who heavily promoted its development. Seven General Assemblies were convoked between 1766 and 1778.[6][7]

In 1767, the British moved the northern boundary to the 32° 28′ north latitude,[3]: 2 extending from the Yazoo to the Chattahoochee River, which included the Natchez District and the Tombigbee District.[8] The appended area included approximately the lower halves of the present states of Mississippi and Alabama. Many new settlers arrived in the wake of the British garrison, swelling the population. In 1774 the First Continental Congress sent letters inviting West Florida to send delegates, but this proposal was declined as the inhabitants were overwhelmingly Loyalist. During the American Revolutionary War, the Governor of West Florida was Peter Chester. The commander of British forces during the war was John Campbell. The colony was attacked in 1778 by the Willing Expedition.

Spanish era

Spain entered the American Revolutionary War on the side of France, but not the Thirteen Colonies.[9] Bernardo de Gálvez, governor of Spanish Louisiana, led a military campaign along the Gulf Coast, capturing Baton Rouge and Natchez from the British in 1779, Mobile in 1780, and Pensacola in 1781.

In the 1783 Treaty of Paris ending the war, the British agreed to a boundary between the United States and West Florida at 31° north latitude between the Mississippi and Apalachicola Rivers. However, a separate Anglo-Spanish agreement, which ceded both Florida provinces back to Spain, did not specify a northern boundary for Florida. Spain insisted that its West Florida claim extended fully to the 1767 boundary at 32° 28′, but the United States asserted that the land between 31° and 32° 28′ had always been British territory.[3]: 2 This sparked the first West Florida Controversy.[4] Negotiations in 1785–1786 between John Jay and Don Diego de Gardoqui failed to reach a satisfactory conclusion. The border was finally resolved in 1795 by the Treaty of San Lorenzo, in which Spain recognized the 31° parallel as the boundary.

Spain continued to maintain East and West Florida as separate colonies. When Spain acquired West Florida in 1783, the eastern British boundary was the Apalachicola River, but Spain moved it eastward to the Suwannee River in 1785.[10][11] The purpose was to transfer the military post at San Marcos (now St. Mark's) and the district of Apalachee from East Florida to West Florida.[5][12]

In the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso of 1800, Spain agreed to return Louisiana to France; however, the location of the boundary between Louisiana and West Florida was not explicitly specified. After France sold Louisiana to the United States in 1803, another boundary dispute erupted. The United States laid claim to the territory from the Perdido River to the Mississippi River, which the Americans believed had been a part of the old province of Louisiana when the French agreed to cede it to Spain in 1762. The Spanish insisted that they had administered that portion as the province of West Florida and that it was not part of the territory restored to France by Charles IV in 1802,[13][14] as France had never given West Florida to Spain, among a list of other reasons.

Republic of West Florida

The United States and Spain held long, inconclusive negotiations on the status of West Florida. In the meantime, American settlers established a foothold in the area and resisted Spanish control. British settlers, who had remained, also resented Spanish rule, leading to a rebellion in 1810 and the establishment for 74 days of the Republic of West Florida.

In West Florida from June to September 1810, many secret meetings of those who resented Spanish rule, as well as three openly held conventions, took place in the Baton Rouge district. Out of those meetings grew the West Florida rebellion and the establishment of the independent Republic of West Florida, with its capital at St. Francisville, in present-day Louisiana, on a bluff along the Mississippi River.

Early in the morning on September 23, 1810, armed rebels stormed Fort San Carlos at Baton Rouge and killed two Spanish soldiers[16] "in a sharp and bloody firefight that wrested control of the region from the Spanish."[17] The rebels unfurled the flag of the new republic, a single white star on a blue field. After the successful attack, organized by Philemon Thomas, plans were made to take Mobile and Pensacola from the Spanish and incorporate the eastern part of the province into the new republic.[18] Reuben Kemper led a small force in an attempt to capture Mobile, but the expedition ended in failure.

Support for the revolt was far from unanimous. The presence of competing pro-Spanish, pro-American, and pro-independence factions, as well as the presence of scores of foreign agents, contributed to a "virtual civil war within the Revolt as the competing factions jockeyed for position."[17] The faction that favored the continued independence of West Florida secured the adoption of a constitution at a convention in October.[19] The convention had earlier commissioned an army under General Philemon Thomas to march across the territory, subdue opposition to the insurrection, and seek to secure as much Spanish-held territory as possible. "Residents of the western Florida Parishes proved largely supportive of the Revolt, while the majority of the population in the eastern region of the Florida Parishes opposed the insurrection. Thomas' army violently suppressed opponents of the revolt, leaving a bitter legacy in the Tangipahoa and Tchefuncte River regions."[17]

On November 7, 1810, Fulwar Skipwith was elected as governor, together with members of a bicameral legislature. Skipwith was inaugurated on November 29, 1810. A week later, he and many of his fellow officials still lingered at St Francisville preparing to go to Baton Rouge, where the next session of the legislature was to consider his ambitious program. The impending U.S. takeover apparently came as a surprise to Skipwith when the Mississippi Territory governor, David Holmes, and his party approached the town. Holmes persuaded all except a few leaders, including Skipwith and Philemon Thomas, the general of the West Florida troops, to acquiesce to American authority.[20]

Skipwith complained bitterly to Holmes that, as a result of seven years of U.S. tolerance of continued Spanish occupation, the United States had abandoned its right to the country and that the West Florida people would not now submit to the American government without conditions.[20] Skipwith and several of his unreconciled legislators then departed for the fort at Baton Rouge, rather than surrender the country unconditionally and without terms.[20]

At Baton Rouge on December 9, 1810, Skipwith informed Holmes that he would no longer resist but could not speak for the troops in the fort. Their commander was John Ballinger, who upon the assurance of Holmes that his troops would not be harmed, agreed to surrender the fort. The Orleans Territory governor, William C. C. Claiborne and his armed forces from Fort Adams landed 2 miles (3.2 km) above the town. Holmes reported to Claiborne that "the armed citizens ... are ready to retire from the fort and acknowledge the authority of the United States" without insisting upon any terms. Claiborne agreed to a respectful ceremony to mark the formal act of transfer. Thus, at 2:30 p.m. that afternoon, December 10, 1810, "the men within the fort marched out and stacked their arms and saluted the flag of West Florida as it was lowered for the last time, and then dispersed."[20]

The boundaries of the Republic of West Florida included all territory south of parallel 31°N, east of the Mississippi River and north of the waterway formed by the Iberville River, Amite River, Lake Maurepas, Pass Manchac, Lake Pontchartrain, and the Rigolets. The Pearl River with its branch that flowed into the Rigolets formed the eastern boundary of the republic.[21]

American annexation of the territory

On October 27, 1810, U.S. President James Madison proclaimed that the United States should take possession of West Florida between the Mississippi and Perdido Rivers, based on a tenuous claim that it was part of the Louisiana Purchase.[22] (See The U.S. claim, below.) The West Florida government opposed annexation, preferring to negotiate terms to join the Union. Governor Fulwar Skipwith proclaimed that he and his men would "surround the Flag-Staff and die in its defense".[20]: 308 William C. C. Claiborne was sent to take possession of the territory, entering the capital of St. Francisville with his forces on December 6, 1810, and Baton Rouge on December 10, 1810. Claiborne refused to recognize the legitimacy of the West Florida government, however, and Skipwith and the legislature eventually agreed to accept Madison's proclamation. Congress passed a joint resolution, approved January 15, 1811, to provide for the temporary occupation of the disputed territory and declaring that the territory should remain subject to future negotiation.[14]

On February 12, 1812, Congress secretly authorized President James Madison to take possession of the portion of West Florida located west of the Perdido River that was not already in the possession of the United States, with authorization to use military and naval force as deemed necessary.[23] On April 14, 1812, Congress authorized the portion of the territory west of the Pearl River to be incorporated into the state of Louisiana, which would be formally created on April 30,[24] but it was not formally attached until the state's legislature approved it on August 4.[25] The U.S. annexed the Mobile District of West Florida to the Mississippi Territory on May 14, 1812,[26][27] although this decision was not effected with military force until nearly a year later.[28] (See Major Gen. James Wilkinson's role.) According to one historian, "The incorporation of West Florida into the Orleans district represents the emergence of infant American imperialism by the newly constructed union. Using force, not negotiations, Claiborne and his army, with Madison's proclamation, forced Skipwith and his sympathizers to accept foreign rule."[29]

United States claim

By the secret treaty of October 1, 1800, between France and Spain, known as the St. Ildefonso treaty,[30] Spain returned to France in 1802 the province of Louisiana as at that time possessed by Spain, and such as it was when France last possessed it in 1769.[3]p 48[13] (In contrast, Madison's 1810 proclamation alluded to the time of France's original, not last, possession.)

It is important that in the transfer of Louisiana to the United States, the identical language in Article 3 of the 1800 St. Ildefonso treaty was used. The ambiguity in this third article lent itself to the purpose of U.S. envoy James Monroe, although he had to adopt an interpretation that France had not asserted nor Spain allowed.[4]p 83 Monroe examined each clause of the third article and interpreted the first clause as if Spain since 1783 had considered West Florida as part of Louisiana. The second clause only served to render the first clause clearer. The third clause referred to the treaties of 1783 and 1795, and was designed to safeguard the rights of the United States. This clause then simply gave effect to the others.[4]p 84-85

According to Monroe, France never dismembered Louisiana while it was in her possession. (He regarded November 3, 1762, as the termination date of French possession, rather than 1769, when France formally delivered Louisiana to Spain.) After 1783, Spain reunited West Florida to Louisiana, Monroe held, thus completing the province as France possessed it, with the exception of those portions controlled by the United States. By a strict interpretation of the treaty, therefore, Spain might be required to cede to the United States such territory west of the Perdido as once belonged to France.[4]p 84-85

Counters to the U.S. claim

- As part of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase treaty, France repeated verbatim Article 3 of its 1800 treaty with Spain, thus expressly subrogating the United States to the rights of France and Spain.[31]p 288-291

- In 1800, denominated Louisiana did not include West Florida.[31]p 288-291

- Spain, in all negotiations with France, refused to cede any part of Florida.[31]p 288-291

- In 1801, Spain informed the Spanish governors in North America that the territory ceded to France did not include West Florida.[4]p 87-88

- In Spanish government ordinances and treaties, the Floridas were always specified as distinct from all other Spanish possessions.[3]p 49-50

- France's 1801 Treaty of Aranjuez with Spain stipulated the cession of Louisiana to be a "restoration", not a retrocession.[3]p 50-52

- France never gave any part of Florida to Spain, so Spain could not give it back.[3]p 50-52

- In the time Spain held the Floridas, they were always called the Floridas and never referred to as a portion of Louisiana. Treaties between United States and Spain also called them the Floridas.[3]p 50-52

- In 1803, France began negotiating with Spain to acquire West and East Florida, confirming that France did not consider West Florida to have already been acquired.[3]p 50-52

- During his negotiations with France, U.S. envoy Robert Livingston wrote nine reports to Madison in which he stated that West Florida was not in the possession of France.[3]p 43-44

- President Jefferson asked U.S. officials in the border area for advice on the limits of Louisiana, the best informed of whom did not believe it included West Florida.[4]p 87-88

- When Louisiana was formally delivered to the United States, the U.S. did not demand possession of West Florida.[4]p 97-100

- In the summer of 1804, when the United States and Spain appealed to France to influence the treaty interpretation, Napoleon strongly sided with Spain.[4]p 109-110

- In November 1804, in response to Livingston, France declared the American claim to West Florida absolutely unfounded.[4]p 113-116

- In January 1805, the French and Spanish ambassadors jointly informed Madison that the American claim to West Florida was untenable. Madison pointed to pre-1763 maps that showed West Florida as part of the former French Louisiana territory. The French ambassador pointed out to Madison's dismay that the same applied to Tennessee and Kentucky.[4]p 116-117

- Upon the failure of Monroe's 1804–1805 special mission, Madison was ready to abandon the American claim to West Florida altogether.[4]p 118

- In 1805, Monroe's last proposition to Spain to obtain West Florida was absolutely rejected.[31]p 293

- In an 1809 letter, Jefferson virtually admitted that West Florida was not a possession of the United States.[3]p 46-47

- The U.S. title to the Louisiana territory was itself a vitiated title by virtue of the 1800 France-Spain treaty.[3]p 26

- General Andrew Jackson personally accepted the delivery of title to West Florida from its Spanish governor on July 17, 1821.[32]

Later history and legacy

The Spanish continued to dispute the annexation of the western parts of its West Florida colony, but their power in the region was too weak to do anything about it. They continued administering the remainder of the colony (between the Perdido and Suwannee Rivers) from the capital at Pensacola.

On February 22, 1819, Spain and the United States signed the Adams-Onís Treaty. In this treaty, Spain ceded both West and East Florida to the United States in exchange for compensation and the renunciation of American claims to Texas.[33] Following ratification by Spain on October 24, 1820, and the United States on February 19, 1821, the treaty took effect, thereby establishing the current boundaries.

President James Monroe was authorized on March 3, 1821, to take possession of East Florida and West Florida for the United States and provide for initial governance.[34] As a result, the U.S. military took over and governed both Floridas with Andrew Jackson serving as governor. The United States soon organized the Florida Territory on March 30, 1822, by combining East Florida and the rump West Florida east of the Perdido River and establishing a territorial government.[35] It was then admitted to the Union as a state on March 3, 1845.[36]

West Florida had an effect on choosing the location of Florida's current capital. At first, the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida determined to rotate between the historic capitals of Pensacola and St. Augustine. The first legislative session was held at Pensacola on July 22, 1822; this required delegates from St. Augustine to travel 59 days by sea to attend. To get to the second session in St. Augustine, Pensacola members traveled 28 days over land. During this session, the council decided future meetings should be held at a half-way point to reduce the distance. Eventually, Tallahassee, site of an 18th-century Apalachee settlement, was selected as the midpoint between the former capitals of East and West Florida.[1]

The portions of West Florida now located in Louisiana are known as the Florida Parishes. The Republic of West Florida Historical Museum is located in Jackson, Louisiana, run by the Republic of West Florida Historical Association.[37] In 1991, the lineage society "The Sons & Daughters of the Province & Republic of West Florida 1763–1810" was founded for the descendants of settlers of the period. Its objective included to "collect and preserve records, documents and relics pertaining to the history and genealogy of West Florida prior to December 7, 1810."[38] In 1993, the Louisiana State Legislature renamed Interstate 12, the full length of which is contained in the Florida Parishes, as the "Republic of West Florida Parkway".

In 1998, Leila Lee Roberts, a great-granddaughter of Fulwar Skipwith, donated the original copy of the constitution of the West Florida Republic and the supporting papers to the Louisiana State Archives in Baton Rouge.[39] Southeastern Louisiana University in Hammond also holds an archival collection of documents from British West Florida and the Republic of West Florida, some of them dating back to 1764.[40]

Governors

Governors under British rule:[41]

- George Johnstone (1763–1766)

- Montfort Browne (acting, 1766–1769)

- John Eliot (appointed 1767, arrived April 1769, committed suicide shortly afterward)

- Montfort Browne (acting, 1769)

- Elias Durnford (acting, 1769–1770)

- Peter Chester (1770–1781)

Governors under Spanish rule:[41]

- Arturo O'Neill de Tyrone: (May 9, 1781 – 1794)

- Enrique White: (1794–1796)

- Francisco de Paula Gelabert: (1796)

- Vicente Folch y Juan: (June 1796 – March 1811)

- Francisco San Maxent: (March 1811 – 1812)

- Mauricio de Zúñiga: (1812–1813)

- Mateo González Manrique: (1813–1815)

- José de Soto: (1815–1816)

- Mauricio de Zúñiga: (1816)

- Francisco San Maxent: (1816)

- José Masot: (1816 – May 26, 1818)

- William King: (United States military governor, May 26, 1818 – February 4, 1819)

- José María Callava: (February 4, 1819 – July 17, 1821)

See also

Notes

References

- Gannon, Michael V. (1993). Florida: A Short History. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1167-1.

- The phrase "Louisiana as France possessed it, and as Spain received it" paraphrases a key term in Article III of the Treaty of St. Ildefonso of 1800: "Louisiana, with the same extent that it now has in the hands of Spain and that it had when France possessed it".

- Chambers, Henry E. (May 1898). West Florida and its relation to the historical cartography of the United States. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins Press.

- Cox, Isaac Joslin (1918). The West Florida Controversy, 1798–1813 – a Study in American Diplomacy. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins Press.

- "The Evolution of a State, Map of Florida Counties – 1820". 10th Circuit Court of Florida. Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

Under Spanish rule, Florida was divided by the natural separation of the Suwannee River into West Florida and East Florida.

- The South in the Revolution, 1763–1789 – John Richard Alden – Google Books

- "Spanish colonial St. Augustine". University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries. p. 4.

- The National Archives (British), Discussion of the Privy Council. PC 1/59/5/1

- Spencer Tucker; James R. Arnold; Roberta Wiener (September 30, 2011). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 751. ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8.

- Wright, J. Leitch (1972). "Research Opportunities in the Spanish Borderlands: West Florida, 1781–1821". Latin American Research Review. Latin American Studies Association. 7 (2): 24–34. doi:10.1017/S0023879100041340. JSTOR 2502623. Wright also notes, "It was some time after 1785 before it was clearly established that Suwannee was the new eastern boundary of the province of Apalachee."

- Weber, David J. (1992). The Spanish Frontier in North America. New Haven, Connecticut, USA: Yale University Press. p. 275. ISBN 0300059175.

Spain never drew a clear line to separate the two Floridas, but West Florida extended easterly to include Apalachee Bay, which Spain shifted from the jurisdiction of St. Augustine to more accessible Pensacola.

- Klein, Hank. "History Mystery: Was Destin Once in Walton County?". The Destin Log. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

On July 21, 1821 all of what had been West Florida was named Escambia County, after the Escambia River. It stretched from the Perdido River to the Suwanee River with its county seat at Pensacola.

- Calvo, Carlos (1862). Real cédula expedida en Barcelona, a 15 de octubre de 1802, para que se entregue a la Francia la colonia y provincia de la Luisiana. pp. 326–328.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) On 15 October 1802, Charles IV published a royal bill in Barcelona that made effective the transfer of Louisiana, providing the withdrawal of the Spanish troops in the territory, on condition that the presence of the clergy be maintained and the inhabitants keep their property, - "Treaty of Amity, Settlement, and Limits Between the United States of America and His Catholic Majesty. 1819". Avalon Project, Yale University. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

By the treaty of Saint Ildefonso, made October 1, 1800, Spain had ceded Louisiana to France and France, by the treaty of Paris, signed April 30, 1803, had ceded it to the United States. Under this treaty the United States claimed the countries between the Iberville and the Perdido. Spain contended that her cession to France comprehended only that territory which, at the time of the cession, was denominated Louisiana, consisting of the island of New Orleans, and the country which had been originally ceded to her by France west of the Mississippi. Congress passed a joint resolution, approved January 15, 1811, declaring that the United States, under the peculiar circumstances of the existing crisis, could not, without serious inquietude, see any part of this disputed territory pass into the hands of any foreign power; and that a due regard to their own safety compelled them to provide, under certain contingencies, for the temporary occupation of the disputed territory; they, at the same time, declaring that the territory should, in their hands, remain subject to future negotiation.

— excerpt of website's Footnote (1) - "Florida Parishes". Center for Southeast Louisiana Studies, Southeastern Louisiana University. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- Arthur, Stanley Clisby (1935). The Story of the West Florida Rebellion. St. Francisville, Louisiana, U.S.: St. Francisville Democrat. p. 107.

- "West Florida Bicentennial". Hammond, Louisiana, U.S.: Southeast Louisiana University. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- Sterkx, Henry Eugene; Thompson, Brooks (April 1961). "Philemon Thomas and the West Florida Revolution". Florida Historical Quarterly: 382–385., as cited by Higgs, Robert (June 2005). "The Republic of West Florida: Freedom Fight or Land Grab?" (PDF). The Freeman. 55: 31–32.

- A scholarly edition of the text of the constitution is available. See Dippel; Horst, eds. (2009). Constitutions of the World from the Late 18th Century to the Middle of the 19th Century, Constitutional Documents of the United States of America 1776–1860, Part VII: Vermont – Wisconsin. München: K. G. Sauer Verlag. pp. 143–153. ISBN 978-3-598-44097-7.

- Cox, Isaac Joslin (January 1912). "The American Intervention in West Florida". The American Historical Review. Oxford University Press on behalf of American Historical Association. 17 (2): 290–311. doi:10.1086/ahr/17.2.290. JSTOR 1833000.

- Darby, William; Melish, John (1816). "A Map of the State of Louisiana With Part Of The Mississippi Territory, from Actual Survey By Wm. Darby. Entered ... 8th day of April 1816, by William Darby. Saml. Harrison Sct. Philad. Philadelphia, Published May the 1st 1816, by John Melish". David Rumsey Map Collection. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- "Proclamation 16 – Taking Possession of Part of Louisiana (Annexation of West Florida)"

- "An Act authorizing the President of the United States to take possession of a tract of country lying south of the Mississippi territory and west of the river Perdido"

- "An Act to enlarge the limits of the state of Louisiana"

- "Giving the Assent of the Legislature to an Enlargement of the Limits of the State of Louisiana". en.wikisource.org. August 4, 1812. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (1993). The Jeffersonian Gunboat Navy. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-849-2. p. 101

- "An Act to enlarge the boundaries of the Mississippi territory"

- "West Florida Controversy," in The Columbia-Viking Desk Encyclopedia (1953) New York: Viking.

- Scallions, Cody (Fall 2011). "The Rise and Fall of the Original Lone Star State: Infant American Imperialism Ascendant in West Florida". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 90 (2): 193–220.

- "Treaty of San Ildefonso : October 1, 1800". The Avalon Project. Yale Law School. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- Curry, J. L. M. (April 1888). "The Acquisition of Florida". Magazine of American History. XIX: 286–301.

- Ireland, Gordon (1941). Boundaries, possessions, and conflicts in Central and North America and the Caribbean. New York: Octagon Books. p. 298.

- Britannica Online entry "Transcontinental Treaty

- "An Act for carrying into execution the treaty between the United States and Spain, concluded at Washington on the twenty-second day of February, one thousand eight hundred and nineteen"

- "An Act for the establishment of a territorial government in Florida"

- "An Act for the admission of the States of Iowa and Florida into the Union"

- "The Republic of West Florida Historical Museum". Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- Objectives and Purpose

- Society of American Archivists (May–June 2011). "1810 Document Spurs Louisiana Celebration" (PDF). Archival Outlook: 20. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- "West Florida Republic Collection". Center for Southeast Louisiana Studies. Southeastern Louisiana University. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- John Worth. "Spanish Florida – People – Governors". uwf.edu. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

Bibliography

- Arthur, Stanley Clisby (1935). The Story of the West Florida Rebellion. St. Francisville, LA: St. Francisville Democrat. ISBN 1885480474. — online here

- Bice, David (2004). The Original Lone Star Republic: Scoundrels, Statesmen and Schemers of the 1810 West Florida Rebellion. Jacksonville: Heritage Publishing Consultants. ISBN 1-891647-81-4. OCLC 56994640.

- Bunn, Mike (2020). Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America's Revolutionary Era. Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books. ISBN 978-1588384133.

- Cox, Isaac Joslin (1918). The West Florida Controversy, 1798–1813: A Study in American Diplomacy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 643. OCLC 479174.

- Gannon, Michael (1996). The New History of Florida. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1415-8.

- McMichael, Andrew (Spring 2002). "The Kemper 'Rebellion': Filibustering and Resident Anglo-American Loyalty in Spanish West Florida". Louisiana History. 43 (2): 140.

- McMichael, Andrew (2008). Atlantic Loyalties: Americans in Spanish West Florida, 1785–1810. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-3004-4.

- Scallions, Cody (2011). "The Rise and Fall of the Original Lone Star State: Infant American Imperialism Ascendant in West Florida". Florida Historical Quarterly. 90 (2).

- West Florida Collection, Center for Southeast Louisiana Studies, Linus A. Sims Memorial Library, Southeastern Louisiana University, Hammond. For a summary of the holdings, click here.

External links

- British West Florida Archived December 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, by Robin Fabel (2007) at Encyclopedia of Alabama

- History of West Florida – Histories and Source Documents — includes full text of Arthur (1935) and other materials (compiled by Bill Thayer)

- "Not Merely Perfidious but Ungrateful": The U.S. Takeover of West Florida Archived May 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, by Robert Higgs (2005)

- West Florida, by Ann Gilbert (2003) <--Broken link, February 2017.

- Map of West Florida, 1806, by John Cary

- A Page of History from the Deepest of the Deep South – British West Florida, by Charlsie Russell (2006)

- The Sons & Daughters of the Province & Republic of West Florida 1763 – 1810 — Republic of West Florida descendants' organization