William Utermohlen

William Charles Utermohlen (December 5, 1933 – March 21, 2007) was an American figurative artist known for his late-period self-portraits completed after his 1995 diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease. He had developed progressive memory loss four years before in 1991, and during that time began a series of self-portraits influenced in part by the figurative painter Francis Bacon and cinematographers from the movement of German Expressionism.

William Utermohlen | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, mixed media on paper, 1967 | |

| Born | William Charles Utermohlen December 5, 1933 South Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | March 21, 2007 (aged 73) London, England |

| Citizenship |

|

| Education | Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts |

| Years active | 1957–2002 |

| Known for | Drawing self-portraits after his diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease |

| Spouse |

Patricia Redmond (m. 1965) |

| Signature | |

| |

Born to first-generation German immigrants in South Philadelphia, Utermohlen earned a scholarship at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) in 1951. After completing military service, he spent 1953 studying in Western Europe where he was inspired by Renaissance and Baroque artists. He moved to London in 1962 and married the art historian Patricia Redmond in 1965. He relocated to Massachusetts in 1972 to teach art at Amherst College before returning to London in 1975.

Utermohlen died in obscurity on March 21, 2007, aged 73, but his late works have gained posthumous renown. His self-portraits especially are seen as important in the understanding of the gradual effects of neurocognitive disorders.

Early life

William Charles Utermohlen was born on December 5, 1933,[1][2] in Southern Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as the only child of first-generation German immigrants.[3] At the time, that section of Philadelphia was split along language lines; his family would have been in the German-speaking part of the city, but inward migration across the United States resulted in them living in the Italian bloc. Due to racial tensions, Utermohlen's parents did not allow him to venture outside of his immediate surrounding. Manu Sharma of STIRworld speculates that his parents' protectiveness may have a factor in the development of his artistic creativity.[4]

He earned a scholarship at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) in 1951 where he studied under the realist artist Walter Stuempfig.[5] Utermohlen completed his military service in 1953,[6] following two years in the Caribbean. Shortly after, he studied in Europe, traveling through Italy, France and Spain where he was heavily influenced by the works of Giotto and Nicolas Poussin.[7] He graduated from PAFA in 1957 and moved to England,[8] in part because he was attracted to the London art scene.[9] Utermohlen's wife, the art historian Patricia Redmond, said that "when he was at art school, he was very pretty, and he was chased around by all the homosexual tutors and everybody else... he didn't care but he didn't fancy them. When he came to England he discovered, amazingly, because the English had always been like this, that we quite liked girlish men."[10]

He attended the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford between 1957 and 1959, where he met the American artist R. B. Kitaj.[11][lower-alpha 2] After leaving Ruskin, he returned to the U.S. for three years.[13] He moved to London in 1962 where he met Redmond, whom he married in 1965.[14][lower-alpha 1] In 1969, his artwork was featured in an exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery.[16] From 1972, Utermohlen taught art at the Amherst College in Massachusetts,[17][lower-alpha 3] where Redmond received her master's degree.[19] By 1975 he had returned England, and lived in London where he gained nationality in 1992.[20][21]

Style

His early works are mostly figurative;[22] although James M. Stubenrauch described Utermohlen's early art as "exuberant, at times surrealistic" style of expressionism.[23] For a period in the late 1970s, as a response to the photorealist movement, he printed photographs onto a canvas and painting directly over the photograph. An example of this technique can be seen in Self-Portrait (Split) (1977). He would employ this technique for two portraits of Redmond.[24]

Regarding Utermohlen's art style, Redmond said to The New York Times that "he was never quite in the same time slot with what was going on. Everybody was Abstract expressionist, [while] he was solemnly drawing the figure."[25] She explained in a Studio 360 interview that Utermohlen was "puzzled and worried, because he couldn't work in [a] totally abstract way," as he considered the figure "incredibly important."[26]

Six cycles

_by_William_Utermohlen.jpg.webp)

Utermohlen did not explain his work or discuss them with Redmond. She later said that as an art historian, he feared she would interfere with his creative progress. Redmond believes he was "absolutely right" in this approach, and guesses she would have highlighted faults in his work.[27] Most of his early paintings can be grouped into six cycles: Mythological (1962–1963), Cantos (or Dante) (1964–1966), Mummers (1969–1970), War (1972–1973), Nudes (1973–1974),[lower-alpha 4] and Conversation (1989–1991).[29]

The Mythological series mainly consist of water scenes.[30] The Dante cycle was inspired by Dante's Inferno, while the art style paintings drew influence from pop art.[31] The War series references the Vietnam War;[32] and according to Redmond the inclusion of isolated soldiers represented his feelings of being an outsider in the art scene.[33] Both Mummers and Conversations were based on early memories; the former, completed between 1968 and 1970, is based on the Mummers Parade of Philadelphia.[34] In a letter from November 1970, Utermohlen stated that the cycle was also created as a "vehicle for expressing my anxiety".[35] Redmond described Mummers as "an empathetic vision of the lower classes, but also his own projected self-image".[33]

The Conversations paintings are described by the French psychoanalyst Patrice Polini as Utermohlen's attempt to describe the events of his life before memory loss.[36] They pre-date his diagnosis, and already indicate the onset of a number of symptoms.[37] Titles such as W9 and Maida Vale reference the names of the district and neighborhood, respectively, that he lived in at the time.[38] The artworks themselves contain more saturated colors and "engaging spacial arrangements", which highlight the actions of the people in the artworks.[39]

Alzheimer's, late works

Utermohlen experienced memory loss while working on the Conversation series. His symptoms ranged from being unable to remember how to wrap his necktie to being unable to find his way back to his apartment.[41] Between 1993 and 1994, he produced a series of lithographs depicting short stories written by World War I poet Wilfred Owen.[42] The figures were more still and mask-like than the Conversation pieces. They consist of a series of disoriented and wounded soldiers,[43] and are described by his art dealer Chris Boicos as a seeming premonition of the artist's dementia diagnosis made in the following year.[44] By this time, he was often forgetting to show up for teaching appointments.[45]

In 1994 he took on a commission for a family portrait. Around a year later, Redmond took his client to Utermohlen's studio to see the progress, but saw that the portrait had not advanced since their last viewing nine months earlier.[46] Redmond feared Utermohlen was depressed and sought medical advice.[47] He was diagnosed with probable Alzheimer's disease[48] in August 1995 at the age of 61.[49][50][lower-alpha 5] He was sent to the Queen's Square Hospital where a nurse, Ron Isaacs, became interested in his drawings and asked him to start drawing self-portraits.[52] The first, Blue Skies, was completed between 1994 and 1995, before his diagnosis,[53] and shows him gripping a yellow table in an empty, sparsely described interior.[7] When his neuropsychologist Sebastian Crutch visited Utermohlen in late 1999, he described the painting as depicting the artist trying to hang on and avoid being "swept out" of the open window above.[54] Polini likened the depiction of him holding onto the table to a painter holding onto his canvas, saying that "[i]n order to survive, he must be able to capture this catastrophic moment; he must depict the unspeakable."[55] Blue Skies became Utermohlen's last "large scale" painting.[56]

That year's sketch, A Welcoming Man, shows a disassembled figure that seems to represent his loss of spatial perception.[57] Regarding the sketch, Crutch et al stated that "[Utermohlen] acknowledged that there was a problem with the sketch, but did not know what the problem was nor how it could be rectified."[58] He began a series of self-portraits after his diagnosis in 1995.[59] The earliest, the Masks series, are in watercolor and were completed between 1994 and 2001.[60] His last non-self-portrait dates 1997, and was of Redmond.[61] It was titled by Patrice Polini as Pat (Artist's Wife).[62]

Death

Utermohlen had retired from painting by December 2000,[63] could no longer draw by 2002, and was in the care of the Princess Louise nursing home in 2004.[12] He died of pneumonia at the Hammersmith Hospital on March 21, 2007, aged 73.[21] Redmond said that "really he was dead long before that, Bill died in 2000, when the disease meant he was no longer able to draw."[64]

Later work

Self-portraits

[Dementia] makes me anxious because I like to produce good work and I know good work, but it's just so sad when you feel you cannot do it... It was in sense of opportunity to have something so interesting to happen to you... You have to approach something like this positively and throw yourself into it... It's not fighting back, you can't fight it. But I wanted to understand what was happening to me in the only way I can.[65]

William Utermohlen, 2001 interview with Margaret Discroll

His series of self-portraits became increasingly abstract as his dementia progressed,[66] and according to the critic Anjan Chatterjee, describe "haunting psychological self-expressions."[67] The early stages of the disease had not impacted his ability to paint, despite what was observed by Crutch et al.[68] His cognitive disorder is not believed to have been hereditary; aside from a 1989 car accident which left him unconscious for around 30 minutes, Utermohlen's medical history was described by Crutch as "unremarkable".[69] Redmond covered the mirrors in their house because Utermohlen was afraid of what he saw there, and had stopped using them for self-portraits.[70] After Utermohlen's diagnosis, descriptions of his skull became a key aspect of his self-portraits,[71] while the academic Robert Cook–Deegan noticed how as Utermohlen's condition progressed, he "gradually integrates less colour".[72]

_-_William_Utermohlen.jpg.webp)

The later self-portraits have thicker brushwork than his earlier works.[58] Writing for the Queen's Quarterly, the journalist Leslie Millin noted that the works became progressively more distorted but less colorful.[73] In Nicci Gerrard's 2019 book, What Dementia Teaches Us About Love, she describes the self-portraits as emotional modernism.[74] Sharma suggests that they depict anosognosia, a condition that results both loss of self-recognition and object-recognition.[75]

In Self Portrait (In The Studio) (1996), frustration and fear are evident in his expressions.[76] Xi Hsu speculates that Utermohlen created this self portrait to express that he did not want to be known for his struggles with dementia, and wanted to be known as an artist.[77] His 1996 Self Portrait (With Easel),[lower-alpha 6] shows more confused emotions according to Green et al.[76] Polini describes the appearance of the easel in Self Portrait (With Easel) as akin to prison bars.[80] A 1996 drawing, Broken Figure contains a ghost-like figure which serves as the outline of the fallen body in the drawing.[81] His Self Portrait with Saw (1997) has a serrated carpenter's saw in the far right,[82] which Redmond said invokes an autopsy that would have given a definite diagnosis.[83] Polini noticed how the saw is vertically pointed, similar to a guillotine blade, and wrote that it may symbolise the "approach of a prefigured death".[84][lower-alpha 7] The last self portrait that Utermohlen used a mirror for,[86] Self Portrait (With Easel) (1998) uses the same pose as a 1955 self-portrait. According to Polini, this was the artist's desire to "experience again the old motions of painting."[87]

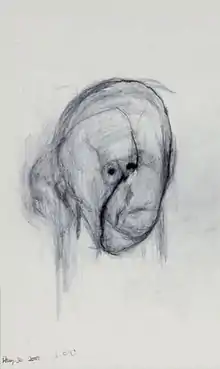

Erased Self Portrait (1999)[lower-alpha 8] was his last attempt at a self-portrait using a paint brush.[89] It took nearly two years to complete[90] and is described by the BBC as "almost sponge like and empty".[91] Head I[lower-alpha 9] (2000) shows a head portraying eyes, mouth, and a smudge on the left that appears to be an ear;[59] a crack appearing in the centre of the head.[93] The rest of the portraits are of a blank head, one of them erased.[59] Associated Press' Joann Loviglio describes Utermohlen's final self-portraits as the "afterimages of a creative and talented spirit whose identity appears to have vanished."[94]

Influences

Redmond describes these works as influenced by German Expressionism, and compares them to artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde.[95] She explained in New Statesman: "It's odd, because he hardly ever thought of his German ancestry, but toward the end he becomes a kind of German abstract expressionist. He might have been quite amused by that, I think."[96]

Shortly after his diagnosis, he and Redmond travelled to Europe and saw Diego Velázquez's 1650 Portrait of Pope Innocent X,[97] which lead to an interest in Francis Bacon's distorted 1953 version Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X.[98] After his return to England in 1996, he painted Self Portrait (In the Studio), which includes the screaming mouth, a motif borrowed from Bacon's work.[99]

A 2015 Scientific American article which mentioned both Bacon and Utermohlen called Bacon's "distorted faces and disfigured bodies" disturbing. It noted that his works are "so distorted that they violate the brain's expectations for the body", and went on to discuss the possibility that Bacon had dysmorphopsia.[100] When describing Utermohlen's portraits, the writer said that Utermohlen's portraits offered "a window into the artist's" decline, adding that they were "also heartbreaking in that they expose[d] a mind trying against hope to understand itself despite deterioration".[101]

Legacy

Utermohlen's self-portraits first gained attention after they were described in The Lancet's 2001 case report[102][lower-alpha 10] when the Crutch et al noted that the evident change in artistic ability was "indicative of a process above and beyond normal aging, particularly given his relatively young age at onset". The article further noted that, over five years, the self-portraits showed an "objective deterioration in the quality of the artwork produced".[104] They concluded that the portraits offered "a testament to the resilience of human creativity".[105] Crutch himself said that Utermohlen's works were "more eloquent than anything he could have said with words".[72]

According to Hsu, the portraits are the "highlight of his career".[106] Commenters liken them to those of Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Edvard Munch.[107] Sharma compared the self-portraits to the works of English painter Ivan Seal, noting that the latter's works show objects that "[teeter] on the brink of pure recognition and abstraction."[75] Some writers have also likened the self-portraits to the illustrations of Mervyn Peake;[108] although Demetrios J. Sahlas of Peake Studies noted that Peake's works were different to Utermohlen's, because shown in the works is the "preservation of insight".[109] A 2013 article in The Lancet compared his work to Rembrandts self-portraits, and described Utermohlen as "struggling to preserve his self against age" while also fighting against "inexorable neurodegeneration".[110] Giovanni Frazzetto described Utermohlen's self-portraits as similar to the works of Egon Schiele, explaining that the portraits were "evocative of the shrivelled bodies and diaphanous faces" shown in the latter's work.[111]

Sherri Irvin says that the portraits show "remarkable stylistic features, [rewarding] serious efforts of appreciation and interpretation".[112] Irvin notes that their "formal and aesthetic features", the correlation with Utermohlen's earlier works and their "aptness to interpretation", is what makes the portraits "jointly sufficient to connect them in the right way with past art, [despite] the absence of an express[ed] intention about how they are to be regarded."[113]

Alan E. H. Emery believes that the progressive effects of dementia give neurologists "an opportunity to study how the disease affects an artist's work over time", adding that it also provides a unique method of studying detailed change in perception, and how it can be linked to localised brain functions. He concluded by stating that documenting changes over time with neuroimaging could lead to better understanding of dementia.[114] Medical anthropologist Margaret Lock states that the portraits indicate that "there may be many avenues... that suggest ways in which humans can be protected from the ravages of this condition by means of lifelong social and cultural activities." [115]

Purcell stated that Utermohlen's artwork provided viewers with a "unique glimpse into the effects of a declining brain."[116] Researchers at Illinois Wesleyan University state that Utermohlen's self portraits show that "people with AD can have a strong voice through images."[117] The existence of his earlier self-portraits (which allowed viewers to create a time-lapse of his mental decline) and the idea that his works give a rare view into the mind of an Alzheimer's patient were two aspects contributing to his growing popularity.[118] The 2019 short film Mémorable was inspired by the self-portraits and nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film in 2020.[119][120]

Many also associate Utermohlen's artwork with the 6 stage, 6 hour long album Everywhere at the End of Time, which also touches on Alzheimer's.

Exhibitions

Utermohlen had exhibited long before his diagnosis. His paintings were exhibited at the Lee Nordness Gallery in 1968 and the Marlborough Gallery in 1969; in 1972, the Mummers cycle was displayed in Amsterdam.[16] Utermohlen's posthumous portrait of Gerald Penny was featured in the Gerald Penny 77' Center;[121] earlier that year, he had artworks such as Five Figures in the Mead Art Museum.[122] At their peak, sales of Utermohlen's earlier works ranged from $3,000 to $30,000.[123]

His self-portraits have been shown at several exhibitions in the years after his death, including 12 exhibitions from 2006 to 2008.[124] In 2016, the exhibition A Persistence of Memory was shown at the Loyola University Museum of Art in Chicago.[125] The exhibition, which contained 100 artworks from Utermohlen's work, was organised by Pamela Ambrose,[126] who said about his portraits: "If you did not know that this man was suffering from Alzheimer's, you could simply perceive the work as a stylistic change."[127]

Other notable exhibitions include a retrospective at the GV Art gallery in London in 2012,[128][lower-alpha 11] an exhibition at the Chicago Cultural Center in 2008 sponsored by Myriad Pharmaceuticals,[130][131] and The Later Works of William Utermohlen, shown at the New York Academy of Medicine in 2006, which marked the centenary of Alois Alzheimer first discovering the disease;[132] it was open free to the public. Earlier that year, there was another exhibition at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.[133] His self-portraits have also been shown in Washington, D.C. in 2007,[134] the Two 10 Gallery in London in 2001,[135] Harvard University at Cambridge, Massachusetts in 2005,[136] Boston, and Los Angeles. The self-portraits were exhibited in Sacramento, California in 2008.[137] Utermohlen's artworks were shown in 2016 at the Kunstmuseum Thun in Switzerland.[138] In February 2007, a month before Utermohlen's death, his self-portraits were exhibited at Wilkes University.[139]

See also

- Everywhere at the End of Time (2016–2019), a series of six concept albums reflecting the stages of dementia

- It's Such a Beautiful Day (2012), an experimental film depicting the progressively failing memory and worsening symptoms of the protagonist due to a neurological disease

References

Notes

- Sources conflict over the date of Utermohlen and Redmond's marriage: for example, NBC and New Statesman claims that they married the same year they met.[15]

- According to Margaret Lock, Utermohlen was also influenced by Kitaj's pop art works.[12]

- In Utermohlen's last year at Massachusetts, he was an artist-in-residence.[18]

- Although his earliest Nudes date to 1953, he produced most of the works between 1973 and 1974.[28]

- According to Polini, he was also diagnosed in November of that year.[51]

- Also titled Self Portrait I[78] and Self Portrait (With Easel–Yellow and Green)[79]

- Polini also notes the guillotine theme in Self Portrait (With Easel), comparing the red and yellow lines in the portrait to the shape of a guillotine.[85]

- Joann Loviglio also lists the date of creation as between 1999–2000.[88]

- Also titled just Head,[92] or Self-portrait[60]

- Utermohlen had wanted his works to be a subject of medical research. He willingly engaged in research published by The Lancet, which involved the relationship between the symptoms of the disease and the aesthetics of his work.[103]

- The GV Art gallery had a previous exhibition of Utermohlen's work earlier that year, which was titled William Utermohlen: Artistic Decline Through Alzheimer's.[129]

Citations

- UK Government.

- The Times 2007; Davenhill 2018, p. 318.

- The Wall Street Journal 2012; Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 5; Lock 2015, p. 244.

- Sharma 2020, para. 2.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 5.

- NBC 2006.

- The Wall Street Journal 2012.

- Bradley et al. 2006, p. 152.

- Molinsky 2007, 0:56–1:05.

- Molinsky 2007, 1:06–1:31.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 5; The Times 2007.

- Lock 2015, p. 245.

- The Times 2007.

- The Wall Street Journal 2012; Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 5.

- NBC 2006; Adams 2012.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 6.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, pp. 6–7; NBC 2006.

- The Times 2007, para. 7.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 7; The Wall Street Journal 2012.

- The Times 2007, para. 2.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 7.

- The Times 2007; NBC 2006; Tulle 2004, p. 105.

- Schutte & Stubenrauch 2006, p. 42.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, pp. 7–8.

- Grady 2006, para. 10.

- Molinsky 2007, 1:24–1:35.

- Molinsky 2007, 2:35.

- Utermohlen 2006j.

- Gerlin 2001, para. 23.

- Utermohlen 2006g.

- Utermohlen 2006c.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 8.

- Hsu 2014, p. 114.

- Gerlin 2001, para. 20.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 12.

- Davenhill 2018, p. 305.

- Hsu 2014, pp. 117–118.

- Davenhill 2018, p. 301.

- Polini 2006, p. 4.

- Mackowiak 2018, p. 144.

- Gilhooly & Gilhooly 2021, p. 116; Davenhill 2018, p. 300.

- Davenhill 2018, p. 307; Gerlin 2001.

- Gerlin 2001, para. 25.

- Hsu 2014, p. 116.

- Davenhill 2018, p. 300.

- Gerlin 2001, para. 13–14.

- van Buren et al. 2013, p. 2.

- Crutch, Isaacs & Rossor 2001 "We have reported the case of a 66-year-old man with probable Alzheimer's disease fulfilling DSM-IV criteria."

- Soricelli 2006; Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 24.

- Grady 2006.

- Davenhill 2018, p. 299.

- Schutte & Stubenrauch 2006, p. 42–43; Green et al. 2015, p. 17.

- NBC 2006, para. 6.

- Ball 2017.

- Polini 2006, p. 5; Davenhill 2018, p. 310.

- Adams 2012; The Wall Street Journal 2012.

- Hsu 2014, pp. 112–113.

- Crutch, Isaacs & Rossor 2001, p. 2130.

- Boicos 2016.

- Davenhill 2018, p. 317.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 25.

- Polini 2006, p. 9.

- Derbyshire 2001; BBC 2001b.

- Purcell 2012, para. 1.

- Hsu 2014, p. 123.

- Gerrard 2015; Ingram 2003, p. 312.

- Chatterjee 2015, p. 487.

- Hsu 2014, pp. 111–112.

- Crutch, Isaacs & Rossor 2001, p. 2129.

- Hsu 2014, p. 121.

- Purcell 2012, para. 5.

- Cook-Deegan 2018, p. 65.

- Millin 2007, para. 3.

- Hale 2019, para. 7.

- Sharma 2020, para. 4.

- Green et al. 2015, p. 11.

- Hsu 2014, p. 129.

- Davenhill 2018, p. 311; Loviglio 2006, p. D1.

- Schutte & Stubenrauch 2006, p. 41.

- Polini 2006, p. 6; Davenhill 2018, p. 312.

- Polini 2006, p. 6.

- Frei, Alvarez & Alexander 2010, p. 675.

- Neurology Today 2006; Hall 2012, p. 54.

- Polini 2006, p. 9; Hsu 2014, p. 118.

- Davenhill 2018, p. 339.

- Polini 2006, p. 11.

- Davenhill 2018, p. 315.

- Loviglio 2006, p. D5.

- NBC 2006; Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 25.

- Soricelli 2006.

- BBC 2001b.

- Schutte & Stubenrauch 2006, p. 43.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 25; Dublin Science Gallery 2016.

- Basting 2009, p. 126.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 24.

- Adams 2012, para. 9.

- Hsu 2014, p. 126.

- Adams 2012.

- Hsu 2014, p. 127.

- Martinez-Conde & Macknik 2015, p. 23.

- Martinez-Conde & Macknik 2015, p. 25.

- The Wall Street Journal 2012; Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 7; Tulle 2004, p. 107.

- Swinnen 2015, p. 147.

- Crutch, Isaacs & Rossor 2001, p. 2132.

- Crutch, Isaacs & Rossor 2001, p. 2133.

- Hsu 2014, p. 111.

- Swinnen 2015, p. 145.

- Forsythe, Williams & Reilly 2017, p. 2.

- Sahlas 2003, p. 10.

- Matthews & Matthews 2015, p. 986.

- Frazzetto 2016, p. 347.

- Irvin 2012, pp. 87–88.

- Irvin 2012, p. 88.

- Emery 2004, p. 371.

- Lock 2015, p. 246.

- Purcell 2012, para. 11.

- Green et al. 2015, p. 17.

- Swinnen 2015, pp. 145–146.

- Grobar 2020; McLean 2020.

- Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences 2020.

- Jackson & Blair 1974, p. 1.

- Iacobuzio 1974, p. 18.

- Gerlin 2001, para. 6.

- Utermohlen, Polini & Boicos 2008, p. 35.

- Thometz 2016.

- Stennett 2016, para. 2.

- Politis 2016, para. 3.

- The Wall Street Journal 2012; Adams 2012.

- Purcell 2012, para. 2.

- Lock 2015, p. 244.

- Swinnen 2015, p. 147, n. 4.

- Neurology Today 2006; NBC 2006; Grady 2006.

- Loviglio 2006, p. D1.

- Molinsky 2007, 8:08–8:18.

- BBC 2001a; Crutch, Isaacs & Rossor 2001, p. 2133.

- Sharp 2017, para. 5; Harvard Art Museums 2005, p. 34.

- Trinity Journal 2008.

- Sharp 2017, para. 5.

- Biebel 2007.

Sources

- "The 92nd Academy Awards – 2020". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. February 9, 2020. Archived from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- Adams, Tim (May 3, 2012). "Review: William Utermohlen (1933–2007); Retrospective". New Statesman. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- Laino, Charlene (December 19, 2006). "Art Portrays Descent into Dementia". American Academy of Neurology. Neurology Today. 6 (24): 22. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- Ball, Philip (March 11, 2017). "Forgetting but not gone: dementia and the arts". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- "A portrait of Alzheimer's". BBC. June 28, 2001. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- "Drawing Dementia". BBC. July 4, 2001. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- Biebel, Mary Therese (February 9, 2007). "Images by Alzheimer's victim displayed at Wilkes". Times Leader. Tribune Content Agency. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via Gale Onefile.

- Boicos, Chris (2016). "William Utermohlen : A Persistence of Memory—Loyola University Museum of Art, Chicago – Chris Boïcos Fine Arts". boicosfinearts.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- Derbyshire, David (June 29, 2001). "Artist charts his slide into dementia". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 28, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- "Self Portraits – Science Gallery Dublin". Dublin Science Gallery. 2016. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- Gerlin, Andrea (August 13, 2001). "Self-portrait with Alzheimer's: As disease destroyed his mind, artist William Utermohlen made himself the subject". The Philadelphia Inquirer. ProQuest 1887098583. Retrieved February 6, 2022 – via ProQuest.

- Gerrard, Nicci (July 19, 2015). "Words fail us: dementia and the arts". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- Grady, Denise (October 24, 2006). "Self-Portraits Chronicle a Descent Into Alzheimer's". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- Green, Jonathan; Montpetit, Mignon A.; Diaz, Joanne; Kooken, Wendy (2015). "Pursuing the Ephemerel, Painting the Enduring; Alzheimer's and the Artwork of William Utermohlen". Illinois Wesleyan University. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- Grobar, Matt (January 28, 2020). "'Memorable' Director Bruno Collet Uses Stop-Motion To Tap Into Aging Painter's Experience Of Dementia". Deadline. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- Hale, Sheila (May 3, 2019). "The self that declines: Stories of dementia: the price of longevity". TLS. Times Literary Supplement. No. 6057. The Times Literary Supplement. pp. 13–14. Retrieved April 19, 2022 – via Gale Academic Onefile.

- Hsu, Xi (2014). "A portrait of dementia: the symptoms of dementia as a model for exploring complex and fluid subjectivity in portrait-painting". Wollongong, New South Wales: University of Wollongong. Archived from the original on March 22, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- Iacobuzio, Ted (June 6, 1974). "Amherst Student, 1974 June 6, Commencement issue". Amherst Student. Amherst College. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2021 – via Amherst College Digital Collections.

- Jackson, Antonio; Blair, Raymond (October 14, 1974). "Amherst Student, 1974 October 14". Amherst Student. Amherst College. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2021 – via Amherst College Digital Collections.

- Loviglio, Joann (April 17, 2006). "Artist puts face on Alzheimer's–his own". The Free Lance–Star. pp. D1, D5. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

- McLean, Thomas J. (February 4, 2020). "Animated Shorts Long on Talent in Oscar Race". Variety. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- Millin, Leslie (Summer 2007). "Idols of the eye". Queen's Quarterly. Vol. 114, no. 2. pp. 259–268. Retrieved March 27, 2022 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- "Artist paints his struggle with Alzheimer's". NBC. March 11, 2006. Archived from the original on September 13, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- Molinsky, Eric (June 8, 2007). "William Utermohlen". Studio 360. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- Polini, Patrice (2006). "William Utermohlen Exhibit Catalog – The Later Works of William Utermohlen: 1995 to 2000" (PDF). Myriad Pharmaceuticals. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 15, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- Politis, Evangeline (2016). "An intimate portrait of Alzheimer's disease". Loyola University Chicago. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- Purcell, Andrew (January 31, 2012). "How an Artist Painted His Decline Into Alzheimer's". New Scientist, published by Gizmodo. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- Sharma, Manu (October 10, 2020). "William Utermohlen's critical works reveal extent of Alzheimer's disease". Stir World. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Sharp, Rob (January 18, 2017). "For Alzheimer's Patients, Art's Therapeutic Effects Are Transformative". Artsy. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- Soricelli, Rhonda L. (November 2006). "Commentary: Academic Medicine". Academic Medicine. 81 (11): 997. doi:10.1097/00001888-200611000-00014. PMID 17065867. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- Stennett, Brooke Pawling (February 22, 2016). "Exhibit showcases Alzheimer's through art". UWIRE. ULOOP. Retrieved March 26, 2022 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- Thometz, Kristen (May 16, 2016). "Arts Program Engages Alzheimer's Patients, Caregivers". WTTW. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- "William Utermohlen; The Times". The Times. May 1, 2007. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- "Portraits at state capitol reveal plight of Alzheimer's sufferers". Trinity Journal. February 20, 2008. Archived from the original on November 21, 2021. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- "William Charles Utermohlen personal appointments". UK Government. Archived from the original on December 4, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- Utermohlen, Patricia; Polini, Patrice; Boicos, Chris (2008). "The Works of William Utermohlen — 1955 to 2000" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- Utermohlen, Patricia (2006c). "Dante Cycle: 1964–1966". www.williamutermohlen.org. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- Utermohlen, Patricia (2006g). "Mythologies and the Sea". www.williamutermohlen.org. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- Utermohlen, Patricia (2006j). "Nude Paintings". www.williamutermohlen.org. Archived from the original on December 21, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- "William Utermohlen (1933–2007) – Retrospective; Wall Street Journal Magazine". The Wall Street Journal. April 19, 2012. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

Journals

- Cook-Deegan, Robert (2018). "Progress Against Alzheimer's Disease?". Issues in Science and Technology. 35 (1): 62–76. JSTOR 26594289.

- Crutch, Sebastian J.; Isaacs, Ron; Rossor, Martin N. (June 30, 2001). "Some workmen can blame their tools: artistic change in an individual with Alzheimer's disease". The Lancet. 357 (9274): 2129–33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05187-4. PMID 11445128. S2CID 36177411.

- Emery, Alan E. H. (December 2004). "How Neurological Disease Can Affect an Artist's Work" (PDF). Practical Neurology. 4 (4): 366–371. doi:10.1111/j.1474-7766.2004.00248.x. S2CID 143346164.

- Forsythe, Alex; Williams, Tasmin; Reilly, Ronan G. (January 2017). "What Paint Can Tell Us" (PDF). Neuropsychology. American Psychological Association. 31 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1037/neu0000303. PMID 28026197. S2CID 36622486.

- Frei, Judith; Alvarez, Sarah E.; Alexander, Michelle B. (December 2010). "Ways of Seeing: Using the Visual Arts in Nursing Education". Journal of Nursing Education. 49 (12): 672–676. doi:10.3928/01484834-20100831-04. PMID 20795611.

- Frazzetto, Giovanni (January 22, 2016). "The damage we do". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 351 (6271): 347. Bibcode:2016Sci...351..347F. doi:10.1126/science.aad9278. S2CID 51608571.

- "Annual Report (Harvard University Art Museums) No. 2005/2006". Harvard Art Museums. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. 2005. JSTOR 4301690.

- Hall, Stephen S. (November 1, 2012). "The Dementia Plague". MIT Technology Review. 115 (6): 50–58. ISSN 2749-649X.

- Ingram, Vernon (July–August 2003). "Alzheimer's Disease: The molecular origins of the disease are coming to light, suggesting several novel therapies". American Scientist. Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society. 91 (4): 312–321. doi:10.1511/2003.26.866. JSTOR 27858242.

- Irvin, Sherry (Winter 2012). "Artwork and Document in the Photography of Louise Lawler". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Wiley; The American Society for Aesthetics; Oxford Journals. 70 (1): 79–90. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6245.2011.01500.x. JSTOR 42635858.

- Martinez-Conde, Susana; Macknik, Stephen L. (April 2015). "Warped Perceptions". Scientific American Mind. Scientific American. 26 (2): 23–25. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0315-23. JSTOR 24946491.

- Matthews, Paul M.; Matthews, Emily A. (March 23, 2015). "Expanding perception through the disordered brain". The Lancet. 381 (9871): 985–986. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60699-6. ISSN 0140-6736. S2CID 54298261.

- Sahlas, Demetrios J. (November 2003). "Diagnosing Mervyn Peake's Neurological Condition". Peake Studies. G. Peter Winnington. 8 (3): 4–20. JSTOR 24776099.

- Schutte, Debra L.; Stubenrauch, James (December 2006). "CE Credit: Alzheimer Disease and Genetics: Anticipating the Questions". The American Journal of Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 106 (12): 40–48. doi:10.1097/00000446-200612000-00018. JSTOR 29744851. PMID 17133003.

- van Buren, Benjamin; Bromberger, Bianca; Potts, Daniel; Miller, Bruce; Chatterjee, Anjan (February 2013). "Changes in Painting Styles of Two Artists With Alzheimer's Disease". Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. Educational Publishing Foundation. 7 (1): 89–94. doi:10.1037/a0029332.

Bibliography

- Basting, Anne Davis (July 2009). Forget Memory; Creating Better Lives for People with Dementia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-801-89649-1.

- Bradley, Ronald J.; Harris, R. Adron; Jenner, Peter; Rose, F. Clifford (May 19, 2006). The Neurobiology of Painting: International Review of Neurobiology. Boston: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-046361-2.

- Chatterjee, Anjan (March 2015). The Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Aesthetics and the Arts. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-20705-8.

- Davenhill, Rachael (October 8, 2018). Looking into Later Life. Place of publication not known: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-91582-6.

- Gilhooly, Kenneth J.; Gilhooly, Mary L. M. (August 2021). Aging and Creativity. London: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-128-16615-4.

- Lock, Margaret (October 20, 2015). The Alzheimer Conundrum – Entanglements of Dementia and Aging. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16847-0.

- Mackowiak, Philip A. (November 29, 2018). Patients as Art; Forty Thousand Years of Medical History in Drawings, Paintings, and Sculpture. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-190-85823-0.

- Swinnen, Aagje (2015). Popularizing Dementia; Public Expressions and Representations of Forgetfulness. Bielefeld: transcript. ISBN 978-3-839-42710-1.

- Tulle, Emmanuelle (2004). Old Age and Agency. New York, N. Y.: Nova Science. ISBN 978-1-590-33884-1.