Shaken baby syndrome

Shaken baby syndrome (SBS), also known as abusive head trauma (AHT), is the leading cause of fatal head injuries in children younger than two years.[4] Diagnosing the syndrome has continuously proved both challenging and contentious for medical professionals, in that they often require objective witnesses to the initial trauma or rely on uncorroborated recounting.[5] This is said to be particularly problematic when the trauma is deemed 'non accidental'.[6] Some medical professionals propose that SBS is the result of respiratory abnormalities leading to hypoxia and swelling of the brain [7] However, the courtroom has become a forum for conflicting theories with which generally accepted medical literature has not been reconciled.[4] Often there are no visible signs of trauma.[1] Complications include seizures, visual impairment, cerebral palsy, cognitive impairment, and death.[2][1]

| Shaken baby syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | abusive head trauma, non accidental head injury |

| |

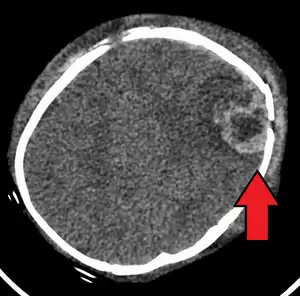

| An intraparenchymal bleed with overlying skull fracture from shaken baby syndrome | |

| Symptoms | Variable[1] |

| Complications | Seizures, visual impairment, cerebral palsy, cognitive impairment[2][1] |

| Usual onset | Less than 5 years old[3] |

| Causes | Blunt trauma, vigorous shaking[1] |

| Diagnostic method | CT scan[1] |

| Prevention | Educating new parents[1] |

| Prognosis | Long term health problems common[3] |

| Frequency | 3 per 10,000 babies per year (US)[1] |

| Deaths | ≈25% risk of death[3] |

The cause may be blunt trauma, vigorous shaking, or a combination of both.[1] Often this occurs as a result of a caregiver becoming frustrated due to the child crying.[3] Diagnosis can be difficult as symptoms may be nonspecific.[1] A CT scan of the head is typically recommended if a concern is present.[1] If there are concerning findings on the CT scan, a full work-up for child abuse should occur, including an eye exam and skeletal survey. Retinal hemorrhage is highly associated with AHT, occurring in 78% of cases of AHT versus 5% of cases of non-abusive head trauma.[8][9]

Educating new parents appears to be beneficial in decreasing rates of the condition.[1] SBS is estimated to occur in three to four per 10,000 babies a year.[1] It occurs most frequently in those less than five years of age.[3] The risk of death is about 25%.[3] The diagnosis include retinal bleeds, multiple fractures of the long bones, and subdural hematomas (bleeding in the brain).[10] These signs have evolved through the years as the accepted and recognized signs of child abuse. Medical professionals strongly suspect shaking as the cause of injuries when a young child presents with retinal bleed, fractures, soft tissue injuries, or subdural hematoma that cannot be explained by accidental trauma or other medical conditions.[11]

Retinal hemorrhage (bleeding) occurs in around 85% of SBS cases and the severity of retinal hemorrhage correlates with severity of head injury.[8] The type of retinal bleeds are often believed to be particularly characteristic of this condition, making the finding useful in establishing the diagnosis.[12]

Fractures of the vertebrae, long bones, and ribs may also be associated with SBS.[13] Dr. John Caffey reported in 1972 that metaphyseal avulsions (small fragments of bone torn off where the periosteum covering the bone and the cortical bone are tightly bound together) and "bones on both the proximal and distal sides of a single joint are affected, especially at the knee".[14]

Infants may display irritability, failure to thrive, alterations in eating patterns, lethargy, vomiting, seizures, bulging or tense fontanels (the soft spots on a baby's head), increased size of the head, altered breathing, and dilated pupils.

Risk factors

Caregivers that are at risk for becoming abusive often have unrealistic expectations of the child and may display "role reversal", expecting the child to fulfill the needs of the caregiver.[15] Substance abuse and emotional stress, resulting for example from financial troubles, are other risk factors for aggression and impulsiveness in caregivers.[15] Caregivers of any gender can cause SBS.[15] Although it had been previously speculated that SBS was an isolated event, evidence of prior child abuse is a common finding.[15] In an estimated 33–40% of cases, evidence of prior head injuries, such as old intracranial bleeds, is present.[15]

Mechanism

Effects of SBS are thought to be diffuse axonal injury, oxygen deprivation and swelling of the brain,[16] which can raise pressure inside the skull and damage delicate brain tissue, although witnessed shaking events have not led to such injuries.

Traumatic shaking occurs when a child is shaken in such a way that its head is flung backwards and forwards.[17] In 1971, Guthkelch, a neurosurgeon, hypothesized that such shaking can result in a subdural hematoma, in the absence of any detectable external signs of injury to the skull.[17] The article describes two cases in which the parents admitted that for various reasons they had shaken the child before it became ill.[17] Moreover, one of the babies had retinal hemorrhages.[17] The association between traumatic shaking, subdural hematoma and retinal hemorrhages was described in 1972 and referred to as whiplash shaken infant syndrome.[17] The injuries were believed to occur because shaking the child subjected the head to acceleration–deceleration and rotational forces.[17]

Force

There has been controversy regarding the amount of force required to produce the brain damage seen in SBS. There is broad agreement, even amongst skeptics, that shaking of a baby is dangerous and can be fatal.[18][19][20]

A biomechanical analysis published in 2005 reported that "forceful shaking can severely injure or kill an infant, this is because the cervical spine would be severely injured and not because subdural hematomas would be caused by high head rotational accelerations... an infant head subjected to the levels of rotational velocity and acceleration called for in the SBS literature, would experience forces on the infant neck far exceeding the limits for structural failure of the cervical spine. Furthermore, shaking cervical spine injury can occur at much lower levels of head velocity and acceleration than those reported for SBS."[21] Other authors were critical of the mathematical analysis by Bandak, citing concerns about the calculations the author used concluding "In light of the numerical errors in Bandak's neck force estimations, we question the resolute tenor of Bandak's conclusions that neck injuries would occur in all shaking events."[22] Other authors critical of the model proposed by Bandak concluding "the mechanical analogue proposed in the paper may not be entirely appropriate when used to model the motion of the head and neck of infants when a baby is shaken."[23] Bandak responded to the criticism in a letter to the editor published in Forensic Science International in February 2006.[24]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be difficult as symptoms may be nonspecific.[1] A CT scan of the head is typically recommended if a concern is present.[1] It is unclear how useful subdural haematoma, retinal hemorrhages, and encephalopathy are alone at making the diagnosis.[25]

A skull fracture from abusive head trauma in an infant

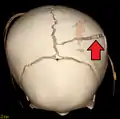

A skull fracture from abusive head trauma in an infant 3D CT reconstruction showing a skull fracture in an infant

3D CT reconstruction showing a skull fracture in an infant 3D CT reconstruction showing a skull fracture in an infant

3D CT reconstruction showing a skull fracture in an infant

Triad

While the findings of SBS are complex and many,[26] they are often incorrectly referred to as a "triad" for legal proceedings; distilled down to retinal hemorrhages, subdural hematomas, and encephalopathy.[27]

SBS may be misdiagnosed, underdiagnosed, and overdiagnosed,[28] and caregivers may lie or be unaware of the mechanism of injury.[15] Commonly, there are no externally visible signs of the condition.[15] Examination by an experienced ophthalmologist is critical in diagnosing shaken baby syndrome, as particular forms of ocular bleeding are strongly associated with AHT.[29] Magnetic resonance imaging may also depict retinal hemorrhaging[30] but is much less sensitive than an eye exam. Conditions that are often excluded by clinicians include hydrocephalus, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), seizure disorders, and infectious or congenital diseases like meningitis and metabolic disorders.[31][32] CT scanning and magnetic resonance imaging are used to diagnose the condition.[15] Conditions that often accompany SBS/AHT include classic patterns of skeletal fracturing (rib fractures, corner fractures), injury to the cervical spine (in the neck), retinal hemorrhage, cerebral bleed or atrophy, hydrocephalus, and papilledema (swelling of the optic disc).[16]

The terms non-accidental head injury or inflicted traumatic brain injury have been used in place of "abusive head trauma" or "SBS".[33]

Classification

The term abusive head trauma (AHT) is preferred as it better represents the broader potential causes.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identifies SBS as "an injury to the skull or intracranial contents of an infant or young child (< 5 years of age) due to inflicted blunt impact and/or violent shaking".[34] In 2009, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended the use of the term AHT to replace SBS, in part to differentiate injuries arising solely from shaking and injuries arising from shaking as well as trauma to the head.[35]

The Crown Prosecution Service for England and Wales recommended in 2011 that the term shaken baby syndrome be avoided and the term non accidental head injury (NAHI) be used instead.[36]

Vitamin C deficiency

Some authors have suggested that certain cases of suspected shaken baby syndrome may result from vitamin C deficiency.[37][38][39] This contested hypothesis is based upon a speculated marginal, near scorbutic condition or lack of essential nutrient(s) repletion and a potential elevated histamine level. However, symptoms consistent with increased histamine levels, such as low blood pressure and allergic symptoms, are not commonly associated with scurvy as clinically significant vitamin C deficiency. A literature review of this hypothesis in the journal Pediatrics International concluded the following: "From the available information in the literature, concluded that there was no convincing evidence to conclude that vitamin C deficiency can be considered to be a cause of shaken baby syndrome."[40]

The proponents of such hypotheses often question the adequacy of nutrient tissue levels, especially vitamin C,[41][42] for those children currently or recently ill, bacterial infections, those with higher individual requirements, those with environmental challenges (e.g. allergies), and perhaps transient vaccination-related stresses.[43] At the time of this writing, infantile scurvy in the United States is practically nonexistent.[44] No cases of scurvy mimicking SBS or sudden infant death syndrome have been reported, and scurvy typically occurs later in infancy, rarely causes death or intracranial bleeding, and is accompanied by other changes of the bones and skin and invariably an unusually deficient dietary history.[45][46]

In one study vaccination was shown not associated with retinal hemorrhages.[47]

Prevention

Interventions by neonatal nurses include giving parents information about abusive head trauma, normal infant crying and reasons for crying, teaching how to calm an infant, and how to cope if the infant was inconsolable may reduce rates of SBS.[52]

Treatment

Treatment involves monitoring intracranial pressure (the pressure within the skull). Treatment occasionally requires surgery, such as to place a cerebral shunt to drain fluid from the cerebral ventricles, and, if an intracranial hematoma is present, to drain the blood collection.[16][1]

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on severity and can range from total recovery to severe disability to death when the injury is severe.[16] One third of these patients die, one third survives with a major neurological condition, and only one third survives in good condition; therefore shaken baby syndrome puts children at risk of long-term disability.[53][54] The most frequent neurological impairments are learning disabilities, seizure disorders, speech disabilities, hydrocephalus, cerebral palsy, and visual disorders.[31]

Epidemiology

Small children are at particularly high risk for the abuse that causes SBS given the large difference in size between the small child and an adult.[15] SBS usually occurs in children under the age of two but may occur in those up to age five.[15] In the US, deaths due to SBS constitute about 10% of deaths due to child abuse.[55]

History

In 1971, Norman Guthkelch proposed that whiplash injury caused subdural bleeding in infants by tearing the veins in the subdural space.[56][57] The term "whiplash shaken infant syndrome" was introduced by Dr. John Caffey, a pediatric radiologist, in 1973,[58] describing a set of symptoms found with little or no external evidence of head trauma, including retinal bleeds and intracranial bleeds with subdural or subarachnoid bleeding or both.[14] Development of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging techniques in the 1970s and 1980s advanced the ability to diagnose the syndrome.[15]

Legal issues

The President's Council of Advisers on Science and Technology (PCAST) noted in its September 2016 report that there are concerns regarding the scientific validity of forensic evidence of abusive head trauma that "require urgent attention".[59] Similarly, the Maguire model, suggested in 2011 as a potential statistical model for determining the probability that a child's trauma was caused by abuse, has been questioned.[60] A proposed clinical prediction rule with high sensitivity and low specificity, to rule out Abusive Head Trauma, has been published.[61]

In July 2005, the Court of Appeals in the United Kingdom heard four appeals of SBS convictions: one case was dropped, the sentence was reduced for one, and two convictions were upheld.[62] The court found that the classic triad of retinal bleeding, subdural hematoma, and acute encephalopathy are not 100% diagnostic of SBS and that clinical history is also important. In the Court's ruling, they upheld the clinical concept of SBS but dismissed one case and reduced another from murder to manslaughter.[62] In their words: "Whilst a strong pointer to NAHI [non-accidental head injury] on its own we do not think it possible to find that it must automatically and necessarily lead to a diagnosis of NAHI. All the circumstances, including the clinical picture, must be taken into account."[63]

The court did not believe the "unified hypothesis", proposed by British physician J. F. Geddes and colleagues, as an alternative mechanism for the subdural and retinal bleeding found in suspected cases of SBS.[62] The unified hypothesis proposed that the bleeding was not caused by shearing of subdural and retinal veins but rather by cerebral hypoxia, increased intracranial pressure, and increased pressure in the brain's blood vessels.[62] The court reported that "the unified hypothesis [could] no longer be regarded as a credible or alternative cause of the triad of injuries": subdural haemorrhage, retinal bleeding and encephalopathy due to hypoxemia (low blood oxygen) found in suspected SBS.[62]

On 31 January 2008, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals granted Audrey A. Edmunds a new trial based on "competing credible medical opinions in determining whether there is a reasonable doubt as to Edmunds's guilt." Specifically, the appeals court found that "Edmunds presented evidence that was not discovered until after her conviction, in the form of expert medical testimony, that a significant and legitimate debate in the medical community has developed in the past ten years over whether infants can be fatally injured through shaking alone, whether an infant may suffer head trauma and yet experience a significant lucid interval prior to death, and whether other causes may mimic the symptoms traditionally viewed as indicating shaken baby or shaken impact syndrome."[64][65]

In 2012, A. Norman Guthkelch, the neurosurgeon often credited with "discovering" the diagnosis of SBS,[66] published an article "after 40 years of consideration," which is harshly critical of shaken baby prosecutions based solely on the triad of injuries.[67] Again, in 2012, Guthkelch stated in an interview, "I think we need to go back to the drawing board and make a more thorough assessment of these fatal cases, and I am going to bet ... that we are going to find in every – or at least the large majority of cases, the child had another severe illness of some sort which was missed until too late."[68] Furthermore, in 2015, Guthkelch went so far as to say, "I was against defining this thing as a syndrome in the first instance. To go on and say every time you see it, it's a crime... It became an easy way to go into jail."[69]

On the other hand, Teri Covington, who runs the National Center for Child Death Review Policy and Practice, worries that such caution has led to a growing number of cases of child abuse in which the abuser is not punished.[66]

In March 2016, Waney Squier, a paediatric neuropathologist who has served as an expert witness in many shaken baby trials, was struck off the medical register for misconduct.[70] Shortly after her conviction, Squier was given the "champion of justice" award by the International Innocence Network for her efforts to free those wrongfully convicted of shaken baby syndrome.[71]

Squier denied the allegations and appealed the decision to strike her off the medical register.[72] As her case was heard by the High Court of England and Wales in October 2016, an open letter to the British Medical Journal questioning the decision to strike off Squier, was signed by 350 doctors, scientists, and attorneys.[73] On 3 November 2016, the court published a judgment which concluded that "the determination of the MPT [Medical Practitioners Tribunal] is in many significant respects flawed".[74] The judge found that she had committed serious professional misconduct but was not dishonest. She was reinstated to the medical register but prohibited from giving expert evidence in court for the next three years.[75]

The Louise Woodward case relied on the "shaken baby syndrome".

References

- Shaahinfar, A; Whitelaw, KD; Mansour, KM (June 2015). "Update on abusive head trauma". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 27 (3): 308–14. doi:10.1097/mop.0000000000000207. PMID 25768258. S2CID 38035821.

- Advanced Pediatric Assessment, Second Edition (2 ed.). Springer Publishing Company. 2014. p. 484. ISBN 9780826161765. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- "Preventing Abusive Head Trauma in Children". www.cdc.gov. 4 April 2017. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- "Consensus Statement: Abusive Head Trauma in Infants and Young Children". Pediatrics. 142 (2). 1 August 2018. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-1504. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 30061300. S2CID 51878771.

- Vinchon, Matthieu (2017). "Shaken Baby Syndrome: What Certainty Do We Have?". Child's Nervous System. 33 (10): 1727–1733. doi:10.1007/s00381-017-3517-8. PMID 29149395. S2CID 22053709.

- Vinchon, Mattieu (2017). "Shaken Baby Syndrome: What Certainty Do We Have?". Child's Nervous System. 33 (10): 1727–1733. doi:10.1007/s00381-017-3517-8. PMID 29149395. S2CID 22053709.

- Dural hemorrhage in non-traumatic infant deaths: does it explain the bleeding in 'shaken baby syndrome'? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003 Feb;29(1):14-22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2003.00434.x. Erratum in: Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003 Jun;29(3):322. PMID 12581336.";>

- Maguire, S A; Watts, P O; Shaw, A D; Holden, S; Taylor, R H; Watkins, W J; Mann, M K; Tempest, V; Kemp, A M (January 2013). "Retinal haemorrhages and related findings in abusive and non-abusive head trauma: a systematic review". Eye. 27 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1038/eye.2012.213. ISSN 0950-222X. PMC 3545381. PMID 23079748.

- Christian, CW; Block, R (May 2009). "Abusive head trauma in infants and children". Pediatrics. 123 (5): 1409–11. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0408. PMID 19403508.

- "NINDS Shaken Baby Syndrome information page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 14 February 2014. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- B.G.Brogdon, Tor Shwayder, Jamie Elifritz Child Abuse and its Mimics in Skin and Bone

- Levin AV (November 2010). "Retinal hemorrhage in abusive head trauma". Pediatrics. 126 (5): 961–70. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1220. PMID 20921069. S2CID 11456829. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014.

- Kempe CH, Silverman FN, Steele BF, Droegemueller W, Silver HK (July 1962). "The battered-child syndrome". JAMA. 181: 17–24. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.589.5168. doi:10.1001/jama.1962.03050270019004. PMID 14455086.

- Caffey J (August 1972). "On the theory and practice of shaking infants. Its potential residual effects of permanent brain damage and mental retardation". American Journal of Diseases of Children. 124 (2): 161–9. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1972.02110140011001. PMID 4559532.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect (July 2001). "Shaken baby syndrome: rotational cranial injuries-technical report". Pediatrics. 108 (1): 206–10. doi:10.1542/peds.108.1.206. PMID 11433079.

- "Shaken Baby Syndrome". Journal of Forensic Nursing. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- Traumatic shaking – The role of the triad in medical investigations of suspected traumatic shaking. www.sbu.se. Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services. 26 October 2016. pp. 9–15. ISBN 978-91-85413-98-0. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- The Royal College of Pathologists. "Report Of A Meeting On The Pathology Of Traumatic Head Injury In Children" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Findley KA, Barnes PD, Moran DA, Squier W (30 April 2012). "Shaken Baby Syndrome, Abusive Head Trauma, and Actual Innocence: Getting It Right". Houston Journal of Health Law and Policy. SSRN 2048374.

- Squier W (2014). ""Shaken Baby Syndrome" and Forensic Pathology". Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology. 10 (2): 248–250. doi:10.1007/s12024-014-9533-z. PMID 24469888. S2CID 41784096.

- Bandak FA (2005). "Shaken Baby Syndrome: A biomechanical analysis of injury mechanisms". Forensic Science International. 151 (1): 71–79. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.02.033. PMID 15885948.

- Margulies S, Prange M, Myers BS, et al. (December 2006). "Shaken baby syndrome: a flawed biomechanical analysis". Forensic Science International. 164 (2–3): 278–9, author reply 282–3. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.12.018. PMID 16436323.

- Rangarajan N, Shams T (December 2006). "Re: shaken baby syndrome: a biomechanics analysis of injury mechanisms". Forensic Science International. 164 (2–3): 280–1, author reply 282–3. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.12.017. PMID 16497461.

- Bandak F (December 2006). "Response to the Letter to the Editor". Forensic Science International. 157 (1): 282–3. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.01.001. which refers to

Margulies S, Prange M, Myers BS, et al. (December 2006). "Shaken baby syndrome: a flawed biomechanical analysis". Forensic Science International. 164 (2–3): 278–9, author reply 282–3. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.12.018. PMID 16436323. - Lynøe, N; Elinder, G; Hallberg, B; Rosén, M; Sundgren, P; Eriksson, A (July 2017). "Insufficient evidence for 'shaken baby syndrome' - a systematic review". Acta Paediatrica. 106 (7): 1021–1027. doi:10.1111/apa.13760. PMID 28130787.

- Greeley, Christopher Spencer (2015). "Abusive Head Trauma: A Review of the Evidence Base". American Journal of Roentgenology. 204 (5): 967–973. doi:10.2214/AJR.14.14191. PMID 25905929.

- Greeley, Christopher Spencer (2014). ""Shaken baby syndrome" and forensic pathology". Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology. 10 (2): 253–255. doi:10.1007/s12024-014-9540-0. PMID 24532195. S2CID 207365843.

- Report questioning shaken baby syndrome seriously unbalanced http://www.aappublications.org/content/36/5/1.2

- "Shaken Baby Syndrome Resources". American Academy of Ophthalmology. Archived from the original on 1 October 2006.

- Zuccoli G; Panigrahy A; Haldipur A; Willaman D; Squires J; Wolford J; Sylvester C; Mitchell E; Lope LA; Nischal KK; Berger RP (July 2013). "Susceptibility weighted imaging depicts retinal hemorrhages in abusive head trauma". Neuroradiology. 55 (7): 889–93. doi:10.1007/s00234-013-1180-7. PMC 3713254. PMID 23568702.

- Oral R (August 2003). "Intentional head trauma in infants: Shaken baby syndrome". Virtual Children's Hospital. Archived from the original (Archived) on 14 February 2005. Retrieved 9 October 2006.

- Togioka BM, Arnold MA, Bathurst MA, et al. (2009). "Retinal hemorrhages and shaken baby syndrome: an evidence-based review". J Emerg Med. 37 (1): 98–106. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.06.022. PMID 19081701.

- Minns RA, Busuttil A (March 2004). "Patterns of presentation of the shaken baby syndrome: Four types of inflicted brain injury predominate". BMJ. 328 (7442): 766. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7442.766. PMC 381336. PMID 15044297.

- Parks, SE; Annest JL; Hill HA; Karch DL (2012). "Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma: Recommended Definitions for Public Health Surveillance and Research". Archived from the original on 8 December 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Abusive Head Trauma: A New Name for Shaken Baby Syndrome Archived 3 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Non Accidental Head Injury Cases (NAHI, formerly referred to as Shaken Baby Syndrome Prosecution Approach Archived 6 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Clemetson CAB (July 2004). "Capillary Fragility as a Cause of Substantial Hemorrhage in Infants" (PDF). Medical Hypotheses and Research. 1 (2/3): 121–129. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- Johnston, C.S. (1996). "Chapter 10) The Antihistamine Action of Ascorbic Acid". Ascorbic Acid; Biochemistry and Biomedical Cell Biology. Vol. 25. Plenum Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-306-45148-5.

- Majno G, Palade GE, Schoefl GI (December 1961). "STUDIES ON INFLAMMATION : II. The Site of Action of Histamine and Serotonin along the Vascular Tree: A Topographic Study". The Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 11 (3): 607–26. doi:10.1083/jcb.11.3.607. PMC 2225127. PMID 14468625.

- Fung EL, Nelson EA (December 2004). "Could Vitamin C deficiency have a role in shaken baby syndrome?". Pediatrics International. 46 (6): 753–5. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200x.2004.01977.x. PMID 15660885. S2CID 35179068.

- Dettman G (March 1978). "Factor "X", sub-clinical scurvy and S.I.D.S. Historical. Part 1". The Australasian Nurses Journal. 7 (7): 2–5. PMID 418769.

- Kalokerinos A, Dettman G (July 1976). "Sudden death in infancy syndrome in Western Australia". The Medical Journal of Australia. 2 (1): 31–2. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1976.tb141561.x. PMID 979792. S2CID 34061797.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) (1991). "Chapter 6 Evidence Concerning Pertussis Vaccines and Other Illnesses and Conditions -- Protracted Inconsolable Crying and Screaming". Adverse Effects of Pertussis and Rubella Vaccines. The National Academies Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-309-04499-8.

- Lee RV (1983). "Scurvy: a contemporary historical perspective". Connecticut Medicine. 47 (10): 629–32, 703–4. PMID 6354581.

- Weinstein M; Babyn Phil; Zlotkin S (2001). "An Orange a Day Keeps the Doctor Away: Scurvy in the Year 2000". Pediatrics. 108 (3): e55. doi:10.1542/peds.108.3.e55. PMID 11533373.

- Rajakumar K (2001). "Infantile Scurvy: A Historical Perspective". Pediatrics. 108 (4): e76. doi:10.1542/peds.108.4.e76. PMID 11581484.

- Binenbaum G (2015). "Evaluation of Temporal Association Between Vaccinations and Retinal Hemorrhage in Children". JAMA Ophthalmol. 133 (11): 1261–1265. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.2868. PMC 4910821. PMID 26335082.

Vaccination injections should not be considered a potential cause of retinal hemorrhage in children, and this unsupported theory should not be accepted clinically or in legal proceedings.

- Cushing H, Goodrich JT (August 2000). "Reprint of "Concerning Surgical Intervention for the Intracranial Hemorrhages of the New-born" by Harvey Cushing, M.D. 1905". Child's Nervous System. 16 (8): 484–92. doi:10.1007/s003810000255. PMID 11007498. S2CID 37717586.

- Williams Obstetrics (1997). "Chapter 20". Diseases and Injuries of the Fetus and Newborn. Vol. 20. Appleton & Lange, Stamford, CT. pp. 997–998. ISBN 978-0-8385-9638-8.

- Williams Obstetrics (2005). "Chapter 29". Diseases and Injuries of the Fetus and Newborn. Vol. 22. McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. 649–691. ISBN 978-0-07-141315-2.

- Looney CB, Smith JK, Merck LH, et al. (February 2007). "Intracranial hemorrhage in asymptomatic neonates: prevalence on MR images and relationship to obstetric and neonatal risk factors". Radiology. 242 (2): 535–41. doi:10.1148/radiol.2422060133. PMID 17179400.

- Allen KA (2014). "The neonatal nurse's role in preventing abusive head trauma". Advances in Neonatal Care (Review). 14 (5): 336–42. doi:10.1097/ANC.0000000000000117. PMC 4139928. PMID 25137601.

- Perkins, Suzanne. (2012). An Ecological Perspective on the Comorbidity of Childhood Violence Exposure and Disabilities: Focus on the Ecology of the School. Psychology of Violence. 2. 75-89. 10.1037/a0026137.

- Keenan Heather T, Runyan DK, Marshall SW, Nocera MA, & Merten DF (2004). A population-based comparison of clinical and outcome characteristics of young children with serious inflicted and noninflicted traumatic brain injury Pediatrics, 114(3), 633–639. [PubMed: 15342832]

- Joyce, Tina; Gossman, William; Huecker, Martin R. (2022). "Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- David TJ (November 1999). "Shaken baby (shaken impact) syndrome: non-accidental head injury in infancy". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 92 (11): 556–61. doi:10.1177/014107689909201105. PMC 1297429. PMID 10703491.

- Integrity in Science: The Case of Dr Norman Guthkelch, 'Shaken Baby Syndrome' and Miscarriages of Justice By Dr Lynne Wrennall Archived 9 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Caffey, John (October 1974). "The Whiplash Shaken Infant Syndrome: Manual Shaking by the Extremities with Whiplash-Induced Intracranial and Intraocular Bleedings, Linked with Residual Permanent Brain Damage and Mental Retardation". Pediatrics. 54 (4): 396–403. doi:10.1542/peds.54.4.396. PMID 4416579. S2CID 36294809. Archived from the original on 13 March 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- Forensic Science in Criminal Courts: Ensuring Scientific Validity of Feature-Comparison Methods (p. 23) "Archived copy" (PDF). Office of Science and Technology Policy. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2016 – via National Archives.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Cuellar M. Causal reasoning and data analysis: Problems with the abusive head trauma diagnosis. Law, Probability and Risk, 2017; 16(4): 223–239. doi:10.1093/lpr/mgx011

- Pfeiffer H, et al. External Validation of the PediBIRN Clinical Prediction Rule of Abusive Head Trauma. Pediatrics, 2018; 141(5): e20173674. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-3674

- De Leeuw M, Jacobs W (2007). "Shaken baby syndrome: The classical clinical triad is still valid in recent court rulings". Critical Care. 11 (Supplement 2): 416. doi:10.1186/cc5576. PMC 4095469.

- "Shaken baby convictions overturned". Special Reports. Guardian Unlimited. 21 July 2005. Retrieved 15 October 2006.

- "Court of Appeals decision - State of Wisconsin v. Audrey A. Edmonds". Wisconsin Court Opinions. Findlaw. 31 January 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- Keith A. Findley Co‐Director, Wisconsin Innocence Project Clinical Professor, University of Wisconsin Law School Litigating Postconviction Challenges to Shaken Baby Syndrome Convictions Archived 15 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Rethinking Shaken Baby Syndrome". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Conversations with Dr. A. Norman Guthkelch". 20 August 2014. Archived from the original on 19 September 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "The Nanny Murder Trial: Retro Report Voices: The Lawyer". New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Oxford doctor Waney Squire vows to fight suspension over 'shaken baby' trial evidence "Oxford doctor struck off over evidence in 'shaken baby' court cases vows to fight suspension". Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- "Shaken baby sceptic begins appeal", BBC News, BBC, 18 October 2016, archived from the original on 25 October 2016, retrieved 24 October 2016

- Sweeney, John (17 October 2016), Should Waney Squier have been struck off over shaken baby syndrome?, BBC, archived from the original on 25 October 2016, retrieved 24 October 2016

- "Case No: CO/2061/2016 Approved Judgement" (PDF). 3 November 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- "Shaken baby evidence doctor reinstated". BBC News. BBC. 3 November 2016. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

External links

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – Abusive head trauma