Allodynia

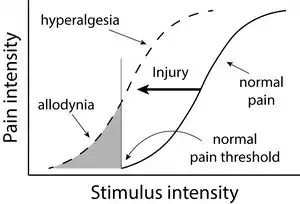

Allodynia is a condition in which pain is caused by a stimulus that does not normally elicit pain.[1] For example, bad sunburn can cause temporary allodynia, and touching sunburned skin, or running cold or warm water over it, can be very painful. It is different from hyperalgesia, an exaggerated response from a normally painful stimulus. The term is from Ancient Greek άλλος állos "other" and οδύνη odúnē "pain".

| Allodynia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Types

There are different kinds or types of allodynia:

- Mechanical allodynia (also known as tactile allodynia)

- Thermal (hot or cold) allodynia – pain from normally mild skin temperatures in the affected area

- Movement allodynia – pain triggered by normal movement of joints or muscles

Causes

Allodynia is a clinical feature of many painful conditions, such as neuropathies,[4] complex regional pain syndrome, postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and migraine. Allodynia may also be caused by some populations of stem cells used to treat nerve damage including spinal cord injury.[5]

Pathophysiology

Cellular level

The cell types involved in nociception and mechanical sensation are the cells responsible for allodynia. In healthy individuals, nociceptors sense information about cell stress or damage and temperature at the skin and transmit it to the spinal cord. The cell bodies of these neurons lie in dorsal root ganglia, important structures located on both sides of the spinal cord. The axons then pass through the dorsal horn to make connections with secondary neurons. The secondary neurons cross over to the other (contralateral) side of the spinal cord and reach nuclei of the thalamus. From there, the information is carried through one or more neurons to the somatosensory cortex of the brain. Mechanoreceptors follow the same general pathway. However, they do not cross over at the level of the spinal cord, but at the lower medulla instead. In addition, they are grouped in tracts that are spatially distinct from the nociceptive tracts.

Despite this anatomical separation, mechanoreceptors can influence the output of nociceptors by making connections with the same interneurons, the activation of which can reduce or eliminate the sensation of pain. Another way to modulate the transmission of pain information is via descending fibers from the brain. These fibers act through different interneurons to block the transmission of information from the nociceptors to secondary neurons.[6]

Both of these mechanisms for pain modulation have been implicated in the pathology of allodynia. Several studies suggest that injury to the spinal cord might lead to loss and re-organization of the nociceptors, mechanoreceptors and interneurons, leading to the transmission of pain information by mechanoreceptors[7][8] A different study reports the appearance of descending fibers at the injury site.[9] All of these changes ultimately affect the circuitry inside the spinal cord, and the altered balance of signals probably leads to the intense sensation of pain associated with allodynia.

Different cell types have also been linked to allodynia. For example, there are reports that microglia in the thalamus might contribute to allodynia by changing the properties of the secondary nociceptors.[10] The same effect is achieved in the spinal cord by the recruitment of immune system cells such as monocytes/macrophages and T lymphocytes.[11]

Molecular level

There is a strong body of evidence that the so-called sensitization of the central nervous system contributes to the emergence of allodynia. Sensitization refers to the increased response of neurons following repetitive stimulation. In addition to repeated activity, the increased levels of certain compounds lead to sensitization. The work of many researchers has led to the elucidation of pathways that can result in neuronal sensitization both in the thalamus and dorsal horns. Both pathways depend on the production of chemokines and other molecules important in the inflammatory response.

An important molecule in the thalamus appears to be cysteine-cysteine chemokine ligand 21 (CCL21). The concentration of this chemokine is increased in the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus where secondary nociceptive neurons make connections with other neurons. The source of CCL21 is not exactly known, but two possibilities exist. First, it might be made in primary nociceptive neurons and transported up to the thalamus. Most likely, neurons intrinsic to the ventral posterolateral nucleus make at least some of it.[10] In any case, CCL21 binds to C-C chemokine receptor type 7 and chemokine receptor CXCR3 receptors on microglia in the thalamus.[12] The physiologic response to the binding is probably the production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) by cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2).[13] Activated microglia making PGE2 can then sensitize nociceptive neurons as manifested by their lowered threshold to pain.[14]

The mechanism responsible for sensitization of the central nervous system at the level of the spinal cord is different from the one in the thalamus. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and its receptor are the molecules that seem to be responsible for the sensitization of neurons in the dorsal horns of the spinal cord. Macrophages and lymphocytes infiltrate the spinal cord, for example, because of injury, and release TNF-alpha and other pro-inflammatory molecules.[15] TNF-alpha then binds to the TNF receptors expressed on nociceptors, activating the MAPK/NF-kappa B pathways. This leads to the production of more TNF-alpha, its release, and binding to the receptors on the cells that released it (autocrine signalling).[11] This mechanism also explains the perpetuation of sensitization and thus allodynia. TNF-alpha might also increase the number of AMPA receptors, and decrease the numbers of GABA receptors on the membrane of nociceptors, both of which could change the nociceptors in a way that allows for their easier activation.[16] Another outcome of the increased TNF-alpha is the release of PGE2, with a mechanism and effect similar to the ones in the thalamus.[17]

Treatment

Medications

Numerous compounds alleviate the pain from allodynia. Some are specific for certain types of allodynia while others are general. They include:[18]

- Dynamic mechanical allodynia – compounds targeting different ion channels; opioids

- Mexiletine

- Lidocaine (IV/topical)

- Tramadol

- Morphine (IV)

- Alfentanil (IV)

- Ketamine (IV)

- Methylprednisone (intrathecal)

- Adenosine

- Glycine antagonist

- Desipramine

- Venlafaxine

- Pregabalin

- Static mechanical allodynia – sodium channel blockers, opioids

- Lidocaine (IV)

- Alfentanil (IV)

- Adenosine (IV)

- Ketamine (IV)

- Glycine antagonist

- Venlafaxine

- Gabapentin (may also be helpful in cold and dynamic allodynias)

- Cold allodynia

- Lamotrigine

- Lidocaine (IV)

The list of compounds that can be used to treat allodynia is even longer than this. For example, many non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as naproxen, can inhibit COX-1 and/or COX-2, thus preventing the sensitization of the central nervous system. Another effect of naproxen is the reduction of the responsiveness of mechano- and thermoreceptors to stimuli.[19]

Other compounds act on molecules important for the transmission of an action potential from one neuron to another. Examples of these include interfering with receptors for neurotransmitters or the enzymes that remove neurotransmitters not bound to receptors.

Endocannabinoids are molecules that can relieve pain by modulating nociceptive neurons. When anandamide, an endocannabinoid, is released, pain sensation is reduced. Anandamide is later transported back to the neurons releasing it using transporter enzymes on the plasma membrane, eventually disinhibiting pain perception. However, this re-uptake can be blocked by AM404, elongating the duration of pain inhibition.[20]

Notable people

- Howard Hughes is thought to have had allodynia in his later years; he seldom bathed, wore clothes, or cut his nails and hair, possibly due to the pain these typically normal actions would cause him.[21]

References

- He, Yusi; Kim, Peggy Y. (2020), "Allodynia", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30725814, retrieved 2020-03-04

- Attal N, Brasseur L, Chauvin M, Bouhassira D (1999). "Effects of single and repeated applications of a eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics (EMLA) cream on spontaneous and evoked pain in post-herpetic neuralgia". Pain. 81 (1–2): 203–9. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00014-7. PMID 10353509. S2CID 1822523.

- LoPinto C, Young WB, Ashkenazi A (2006). "Comparison of dynamic (brush) and static (pressure) mechanical allodynia in migraine". Cephalalgia. 26 (7): 852–6. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01121.x. PMID 16776701. S2CID 9163847.

- Landerholm, A. (2010). Neuropathic pain: Somatosensory Functions related to Spontaneous Ongoing Pain, Mechanical Allodynia and Pain Relief. Thesis. Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet http://diss.kib.ki.se/2010/978-91-7457-025-0/thesis.pdf

- Hofstetter CP, Holmström NA, Lilja JA (March 2005). "Allodynia limits the usefulness of intraspinal neural stem cell grafts; directed differentiation improves outcome". Nature Neuroscience. 8 (3): 346–53. doi:10.1038/nn1405. hdl:10616/38300. PMID 15711542. S2CID 22387113.

- Fitzpatrick, David; Purves, Dale; Augustine, George (2004). Neuroscience. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer. pp. 231–250. ISBN 978-0-87893-725-7.

- Wasner G, Naleschinski D, Baron R (2007). "A role for peripheral afferents in the pathophysiology and treatment of at-level neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury? A case report". Pain. 131 (1–2): 219–25. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.005. PMID 17509762. S2CID 22331115.

- Yezierski RP, Liu S, Ruenes GL, Kajander KJ, Brewer KL (1998). "Excitotoxic spinal cord injury: behavioral and morphological characteristics of a central pain model". Pain. 75 (1): 141–55. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00216-9. PMID 9539683. S2CID 28700511.

- Kalous A, Osborne PB, Keast JR (2007). "Acute and chronic changes in dorsal horn innervation by primary afferents and descending supraspinal pathways after spinal cord injury". J. Comp. Neurol. 504 (3): 238–53. doi:10.1002/cne.21412. PMID 17640046. S2CID 37627042.

- Zhao P, Waxman SG, Hains BC (2007). "Modulation of thalamic nociceptive processing after spinal cord injury through remote activation of thalamic microglia by cysteine cysteine chemokine ligand 21". J. Neurosci. 27 (33): 8893–902. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2209-07.2007. PMC 6672166. PMID 17699671.

- Wei XH, Zang Y, Wu CY, Xu JT, Xin WJ, Liu XG (2007). "Peri-sciatic administration of recombinant rat TNF-alpha induces mechanical allodynia via upregulation of TNF-alpha in dorsal root ganglia and in spinal dorsal horn: the role of NF-kappa B pathway". Exp. Neurol. 205 (2): 471–84. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.012. PMID 17459378. S2CID 54415092.

- Dijkstra IM, de Haas AH, Brouwer N, Boddeke HW, Biber K (2006). "Challenge with innate and protein antigens induces CCR7 expression by microglia in vitro and in vivo". Glia. 54 (8): 861–72. doi:10.1002/glia.20426. PMID 16977602. S2CID 24110610.

- Alique M, Herrero JF, Lucio-Cazana FJ (2007). "All-trans retinoic acid induces COX-2 and prostaglandin E2 synthesis in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells: involvement of retinoic acid receptors and extracellular-regulated kinase 1/2". J Neuroinflammation. 4: 1. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-4-1. PMC 1769480. PMID 17204142.

- Rukwied R, Chizh BA, Lorenz U (2007). "Potentiation of nociceptive responses to low pH injections in humans by prostaglandin E2". J Pain. 8 (5): 443–51. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2006.12.004. PMID 17337250.

- Haskó G, Pacher P, Deitch EA, Vizi ES (2007). "Shaping of monocyte and macrophage function by adenosine receptors". Pharmacol. Ther. 113 (2): 264–75. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.08.003. PMC 2228265. PMID 17056121.

- Stellwagen D, Beattie EC, Seo JY, Malenka RC (2005). "Differential regulation of AMPA receptor and GABA receptor trafficking by tumor necrosis factor-alpha". J. Neurosci. 25 (12): 3219–28. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4486-04.2005. PMC 6725093. PMID 15788779.

- Coutaux A, Adam F, Willer JC, Le Bars D (2005). "Hyperalgesia and allodynia: peripheral mechanisms". Joint Bone Spine. 72 (5): 359–71. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.01.010. PMID 16214069.

- Granot R, Day RO, Cohen ML, Murnion B, Garrick R (2007). "Targeted pharmacotherapy of evoked phenomena in neuropathic pain: a review of the current evidence". Pain Med. 8 (1): 48–64. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00156.x. PMID 17244104.

- Jakubowski M, Levy D, Kainz V, Zhang XC, Kosaras B, Burstein R (2007). "Sensitization of central trigeminovascular neurons: blockade by intravenous naproxen infusion". Neuroscience. 148 (2): 573–83. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.04.064. PMC 2710388. PMID 17651900.

- Hooshmand, Hooshang (1993). Chronic pain: reflex sympathetic dystrophy prevention and managements. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press LLC. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-8493-8667-1.

- Tennant, Forest (July–August 2007). "Howard Hughes & Pseudoaddiction" (PDF). Practical Pain Management. Montclair, New Jersey: PPM Communications, Inc. 6 (7): 12–29. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 25, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2011.