Birth control in the United States

Birth control is a method or device used to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been around since ancient times, but effective and safe forms of birth control have only become available in the 20th century. According to the 2015–2017 National Survey of Family Growth conducted on 72.2 million women between the ages of 15 and 49 in the United States, approximately 64.9% of the sample reported using some method of birth control.[1]

There is a complicated and long history regarding birth control in the United States, in addition to several of the most prominent policies and laws regarding their use.

History

Birth control before 20th century

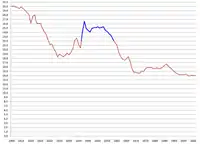

The practice of birth control was common throughout the U.S. prior to 1914, when the movement to legalize contraception began. Longstanding techniques included the rhythm method, withdrawal, diaphragms, contraceptive sponges, condoms, prolonged breastfeeding, and spermicides.[2] Use of contraceptives increased throughout the nineteenth century, contributing to a 50 percent drop in the fertility rate in the United States between 1800 and 1900, particularly in urban regions.[3] The only known survey conducted during the nineteenth century of American women's contraceptive habits was performed by Clelia Mosher from 1892 to 1912.[4] The survey was based on a small sample of upper-class women, and shows that most of the women used contraception (primarily douching, but also withdrawal, rhythm, condoms and pessaries) and that they viewed sex as a pleasurable act that could be undertaken without the goal of procreation.[5]

Although contraceptives were relatively common in middle-class and upper-class society, the topic was rarely discussed in public.[6] The first book published in the United States which ventured to discuss contraception was Moral Physiology; or, A Brief and Plain Treatise on the Population Question, published by Robert Dale Owen in 1831.[7] The book suggested that family planning was a laudable effort, and that sexual gratification – without the goal of reproduction – was not immoral.[8] Owen recommended withdrawal, but he also discussed sponges and condoms.[9] That book was followed by Fruits of Philosophy: The Private Companion of Young Married People, written in 1832 by Charles Knowlton, which recommended douching.[10] Knowlton was prosecuted in Massachusetts on obscenity charges, and served three months in prison.[11]

Birth control practices were generally adopted earlier in Europe than in the United States. Knowlton's book was reprinted in 1877 in England by Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant,[12] with the goal of challenging Britain's obscenity laws.[13] They were arrested (and later acquitted) but the publicity of their trial contributed to the formation, in 1877, of the Malthusian League – the world's first birth control advocacy group – which sought to limit population growth to avoid Thomas Malthus' dire predictions of exponential population growth leading to worldwide poverty and famine.[14] The first birth control clinic in the United States was opened in 1917 by Margaret Sanger, which was against the law at the time.[15] By 1930, similar societies had been established in nearly all European countries, and birth control began to find acceptance in most Western European countries, except Catholic Ireland, Spain, and France.[16] As the birth control societies spread across Europe, so did birth control clinics. The first birth control clinic in the world was established in the Netherlands in 1882, run by the Netherlands' first female physician, Aletta Jacobs.[17] The first birth control clinic in England was established in 1921 by Marie Stopes, in London.[18]

Anti-contraception laws

Contraception was not restricted by law in the United States throughout most of the 19th century, but in the 1870s a social purity movement grew in strength, aimed at outlawing vice in general, and prostitution and obscenity in particular.[19] Composed primarily of Protestant moral reformers and middle-class women, the Victorian-era campaign also attacked contraception, which was viewed as an immoral practice that promoted prostitution and venereal disease.[20] Anthony Comstock, a grocery clerk [21] and leader in the purity movement, successfully lobbied for the passage of the 1873 Comstock Act, a federal law prohibiting mailing of "any article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of abortion" as well as any form of contraceptive information.[22] After passage of this first Comstock Act, he was appointed to the position of postal inspector. Many states also passed similar state laws (collectively known as the Comstock laws), sometimes extending the federal law by additionally restricting contraceptives, including information about them and their distribution. Comstock was proud of the fact that he was personally responsible for thousands of arrests and the destruction of hundreds of tons of books and pamphlets.[23]

These Comstock laws across the states also played a large role in prohibiting contraceptive use and informing to unmarried women as well as the youth. They prevented advertisements about birth control as well as disabling the general sale of them. Because of this unmarried women were not allowed to get a birth control prescription without the permission of their parents until the 1970s.[15]

Comstock and his allies also took aim at the libertarians and utopians who comprised the free love movement – an initiative to promote sexual freedom, equality for women, and abolition of marriage.[24] The free love proponents were the only group to actively oppose the Comstock laws in the 19th century, setting the stage for the birth control movement.[25]

The efforts of the free love movement were not successful and at the beginning of the 20th century, federal and state governments began to enforce the Comstock laws more rigorously.[25] In response, contraception went underground, but it was not extinguished. The number of publications on the topic dwindled, and advertisements, if they were found at all, used euphemisms such as "marital aids" or "hygienic devices". Drug stores continued to sell condoms as "rubber goods" and cervical caps as "womb supporters".[26] In many different states there are different rulings of birth control. Some states do not allow insurance to cover birth control. Most birth control is covered by insurance to ensure that women are getting on birth control if needed.

Birth control movement

From World War II to 1960

After World War II, the birth control movement had accomplished the goal of making birth control legal, and advocacy for reproductive rights began to focus on abortion, public funding, and insurance coverage.[28]

Birth control advocacy organizations around the world also began to collaborate. In 1946, Sanger helped found the International Committee on Planned Parenthood, which evolved into the International Planned Parenthood Federation and soon became the world's largest non-governmental international family planning organization.[29] In 1952, John D. Rockefeller III founded the influential Population Council.[30] Fear of global overpopulation became a major issue in the 1960s, generating concerns about pollution, food shortages, and quality of life, leading to well-funded birth control campaigns around the world.[31] The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development and the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women addressed birth control and influenced human rights declarations which asserted women's rights to control their own bodies.[32]

The sexual revolution and 'the pill'

In the early 1950s, philanthropist Katharine McCormick had provided funding for biologist Gregory Pincus to develop the birth control pill, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1960.[33] In 1960, Enovid (noretynodrel) was the first birth control pill to be approved by the FDA in the United States.[15] The pill became very popular and had a major impact on society and culture. It contributed to a sharp increase in college attendance and graduation rates for women.[34] New forms of intrauterine devices were introduced in the 1960s, increasing popularity of long acting reversible contraceptives.[35]

In 1965, the Supreme Court ruled in Griswold v. Connecticut that it was unconstitutional for the government to prohibit married couples from using birth control.

Also in 1965, 26 states prohibited birth control for unmarried women.[36] In 1967 Boston University students petitioned Bill Baird to challenge Massachusetts's stringent "Crimes Against Chastity, Decency, Morality and Good Order" law.[37] On April 6, 1967, he gave a speech to 1,500 students and others at Boston University on abortion and birth control.[38] He gave a female student one condom and a package of contraceptive foam.[38] Baird was arrested and convicted as a felon, facing up to ten years in jail.[39] He spent three months in Boston's Charles Street Jail.[40] During his challenge to the Massachusetts law, the Planned Parenthood League of Massachusetts stated that "there is nothing to be gained by court action of this kind. The only way to remove the limitations remaining in the law is through the legislative process."[41] Despite this opposition, Baird fought for five years until Eisenstadt v. Baird legalized birth control for all Americans on March 22, 1972. Eisenstadt v. Baird, a landmark right to privacy decision, became the foundation for such cases as Roe v. Wade and the 2003 gay rights victory Lawrence v. Texas.

In 1970, Congress removed references to contraception from federal anti-obscenity laws;[42] and in 1973, the Roe v. Wade decision legalized abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy.[43]

Also in 1970, Title X of the Public Health Service Act was enacted as part of the war on poverty, to make family planning and preventive health services available to low-income and the uninsured.[44] Without publicly funded family planning services, according to the Guttmacher Institute, the number of unintended pregnancies and abortions in the United States would be nearly two-thirds higher; the number of unintended pregnancies among poor women would nearly double.[45] According to the United States Department of Health and Human Services, publicly funded family planning saves nearly $4 in Medicaid expenses for every $1 spent on services.[46]

In 1982, European drug manufacturers developed mifepristone, which was initially utilized as a contraceptive, but is now generally prescribed with a prostoglandin to induce abortion in pregnancies up to the fourth month of gestation.[47] To avoid consumer boycotts organized by anti-abortion organizations, the manufacturer donated the U.S. manufacturing rights to Danco Laboratories, a company formed by pro-abortion rights advocates, with the sole purpose of distributing mifepristone in the U.S, and thus immune to the effects of boycotts.[48]

In 1997, the FDA approved a prescription emergency contraception pill (known as the morning-after pill), which became available over the counter in 2006.[49] In 2010, ulipristal acetate, an emergency contraceptive which is more effective after a longer delay was approved for use up to five days after unprotected sexual intercourse.[50] Fifty to sixty percent of abortion patients became pregnant in circumstances in which emergency contraceptives could have been used.[51] These emergency contraceptives, including Plan B and EllaOne, became another reproductive rights controversy.[52] Opponents of emergency contraception consider it a form of abortion, because it may interfere with the ability of a fertilized embryo to implant in the uterus; while proponents contend that it is not abortion, because the absence of implantation means that pregnancy never commenced.[53]

In 2000, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ruled that companies that provided insurance for prescription drugs to their employees but excluded birth control were violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[54]

President Obama signed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) on 23 March 2010. As of 1 August 2011, female contraception was added to a list of preventive services covered by the ACA that would be provided without patient co-payment. The federal mandate applied to all new health insurance plans in all states from 1 August 2012.[55][56] Grandfathered plans did not have to comply unless they changed substantially.[57] To be grandfathered, a group plan must have existed or an individual plan must have been sold before President Obama signed the law; otherwise they were required to comply with the new law.[58] The Guttmacher Institute noted that even before the federal mandate was implemented, twenty-eight states had their own mandates that required health insurance to cover the prescription contraceptives, but the federal mandate innovated by forbidding insurance companies from charging part of the cost to the patient.[59] The ACA coverage of female contraception has been noted to be beneficial for women. From 2012 to 2016, the percentage of women who did not need to pay for their contraceptives within their private insurance increased from 15% to 67%. This created an increase in accessibility to contraceptives for women, as poor financial status was listed as one of the reasons that women who wanted to use birth control and prevent unplanned pregnancies could not use them. The average yearly price for fuels contraceptive co-pays also reduced from $600 a year to $250 a year. In addition, a nationally representative survey in 2015 indicated that over 70% of women agreed that not having to make out of pocket payments helped with their ability to use birth control and also aided their consistency of use.[60]

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, 573 U.S. ___ (2014), is a landmark decision[61][62] by the United States Supreme Court allowing closely held for-profit corporations to be exempt from a law its owners religiously object to if there is a less restrictive means of furthering the law's interest. It is the first time that the court has recognized a for-profit corporation's claim of religious belief,[63] but it is limited to closely held corporations.[lower-alpha 1] The decision is an interpretation of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and does not address whether such corporations are protected by the free-exercise of religion clause of the First Amendment of the Constitution. For such companies, the Court's majority directly struck down the contraceptive mandate under the ACA by a 5–4 vote.[64] The court said that the mandate was not the least restrictive way to ensure access to contraceptive care, noting that a less restrictive alternative was being provided for religious non-profits, until the Court issued an injunction 3 days later, effectively ending said alternative, replacing it with a government-sponsored alternative for any female employees of closely held corporations that do not wish to provide birth control.[65]

Zubik v. Burwell was a case before the United States Supreme Court on whether religious institutions other than churches should be exempt from the contraceptive mandate. Churches were already exempt.[66] On May 16, 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a per curiam ruling in Zubik v. Burwell that vacated the decisions of the Circuit Courts of Appeals and remanded the case "to the respective United States Courts of Appeals for the Third, Fifth, Tenth, and D.C. Circuits" for reconsideration in light of the "positions asserted by the parties in their supplemental briefs".[67] Because the Petitioners agreed that "their religious exercise is not infringed where they 'need to do nothing more than contract for a plan that does not include coverage for some or all forms of contraception'", the Court held that the parties should be given an opportunity to clarify and refine how this approach would work in practice and to "resolve any outstanding issues".[68] The Supreme Court expressed "no view on the merits of the cases."[69] In a concurring opinion, Justice Sotomayor, joined by Justice Ginsburg noted that in earlier cases "some lower courts have ignored those instructions" and cautioned lower courts not to read any signals in the Supreme Court's actions in this case.[70]

In 2017, the Trump administration issued a ruling letting insurers and employers refuse to provide birth control if doing so went against their religious beliefs or moral convictions.[71] However, later that same year federal judge Wendy Beetlestone issued an injunction temporarily stopping the enforcement of the Trump administration ruling.[72]

Current practices

There are many types of contraceptive methods available. Hormonal methods which contain the hormones estrogen and progestin include oral contraceptive pills (there is also a progestin only pill), transdermal patch (OrthoEvra), and intravaginal ring (NuvaRing). Progestin only methods include an injectable form (Depo-Provera), a subdermal implant (Nexplanon), and the intrauterine device (Mirena). Non-hormonal contraceptive methods include the copper intrauterine device (ParaGard), male and female condoms, male and female sterilization, cervical diaphragms and sponges, spermicides, withdrawal, and fertility awareness.

In 2006–2008, the most popular contraceptive methods among those at risk of unintended pregnancy were oral contraceptive pills (25%), female sterilization (24.2%), male condoms (14.5%), male sterilization (8.8%),[73] intrauterine device (4.9%), withdrawal (4.6%).[73] Depo-Provera is used by 2.9%, primarily younger women (7.5% of those 15-19 and about 4.5% of those 20–30).[73]

A 2013 Lancet systematic literature review found that among reproductive aged women in a marriage or union, 66% worldwide and 77% in the United States use contraception. Due to this, unplanned pregnancies in the United States are at the lowest they have ever been throughout history.[74] However, unintended pregnancy remains high; just under half of pregnancies in the United States are unintended. 10.6% of women at risk of unintended pregnancy did not use a contraceptive method, including 18.7% of teens and 14.3% of those 20–24.[73] Women of reproductive age (15 to 44) who are not regarded as at risk for unintended pregnancy include those who are sterile, were sterilized for non-contraceptive reasons, were pregnant or trying to become pregnant, or had not had sex in the 3 months prior to the survey.[73] When examining reasons why women do not use birth control, a 2007 Pregnancy Risk Monitoring Assessment System (PRAMS) survey of over 8000 women with a recent unintended pregnancy found that 33% felt they could not get pregnant at the time of conception, 30% did not mind if they got pregnant, 22% stated their partner did not want to use contraception, 16% cited side effects, 10% felt they or their partner were sterile, 10% reported access problems, and 18% selected "other".

A 2021 study found disparity among racial groups in the perceived quality of family planning care received, with white women (72%) more likely to rate their experience with their providers as excellent than Black (60%) and Hispanic women (67%).[75]

Cost savings

Contraceptive use saves almost US$19 billion in direct medical costs each year.[76]

Noted benefits on child poverty and the rate of single-family households

Contraceptive use has been shown to reduce the rate of children born into poverty, as parents are able to plan the correct financially stable time in which to have a child. In addition, unplanned pregnancies have been noted to cause splits of parents or child abandonment, which results in single-parent households that are more likely to go through poverty. In fact, between 1970 and 2012 this has resulted in a 25% increase of child poverty rates. One study also concluded that if women under the age of 30 began using birth control pills as a preventative measure against unplanned pregnancies, the child poverty rate could drop around half a percentage point within a year.[74]

Barriers to access

According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), in the United States, around 65 percent of women in the age range from 15 to 49 used a form of contraception [77] including but not limited to permanent sterilization, Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives (LARC), and forms of barriers.[78] Several methods of contraceptives involve procedures of insertion by medical professionals and/or prescriptions, also obtainable from healthcare providers.[78]

According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), there are several factors including age, ethnicity, and education that have an influence over the use and accessibility of birth control methods including female sterilization, the pill, the male condom, and long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs).[77] From data collected in the 2017-2019 National Survey for Family Growth, the statistics of birth control usage with respect to these factors with women ages 15–49 were studied. Higher use of the pill within populations as a contraceptive method was found to be correlated with a younger age range, more higher education attainment, and higher use by people of non-Hispanic origin and race. Higher use of female sterilization within populations as a contraceptive method, though not directly correlated with Hispanic race or origin, was correlated with an older age range and less higher education attainment. Higher use of male condoms though not directly correlated to an age range nor education levels of attainment, was correlated with lower use by non-Hispanic white women. Higher use of LARCs was found to be correlated to higher levels of education attainment, but not significant correlations to age range or Hispanic origin or race.[77]

According to research conducted by the Guttmacher Institute, there is also a link between socioeconomic status in populations of people with sexual and reproductive behavior.[79] In the study, data was collected from adolescents residing in the countries of Canada, France, Great Britain, Sweden and the United States on their socioeconomic status and their varying degrees of sexual activity, including their use of contraceptives. It was found that overall, the use of contraceptives in adolescents in the United States and in Great Britain was lower for populations with economic disadvantages, the gaps between education and use of contraceptives higher in Great Britain than in the United States.[79] In addition, in a study of last-intercourse uses of contraceptives, it was found that Hispanic individuals were less likely to use contraceptives than white and black individuals, with white individuals having the highest use of contraceptives.[79]

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Of the many effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, one of them included is national access to birth control being limited as a result of a slowing of mobility in result of safety precautions for reducing spread of the coronavirus.[80] In addition to transportation limitations preventing many people from accessing procedures in clinics, including IUD and implants as well as abortions,[81] the COVID-19 pandemic also altered the methods of which patients and providers could interact - services often being restricted to virtual visits and appointments, affecting the availability and accessibility of prescription-based forms of birth control, such as the pill.[80]

In addition, due to the COVID-19 Pandemic, fertility rates and birth rates, as well as demand for contraceptives changed compared with amounts pre-pandemic, with more individuals seeking methods of contraception during and immediately after the pandemic, corresponding with lower birth rates.[82] This is a part of an overall trend found in the case of other past pandemics as well, such as SARS, Zika, and the Spanish Flu.[82]

Government and policy

Domestic

- Funding

- Title X

- Medicaid

- Take Charge

- Contraceptive mandates

- Goals

- Healthy People program "responsible sexual behavior" indicator

International

- United States Agency for International Development

2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

In two major legal cases that were planned in 2014, the attorneys made an issue of whether a for-profit corporation can be required to provide coverage for contraceptive services to its employees.[83] As of 1 January 2016, women in Oregon will be eligible to purchase a one-year supply of oral contraceptive; this is the first such legislation in the United States and has attracted the attention of California, Washington state and New York.[84]

Possible new rule under Trump administration

In 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services changed the previous federal requirement for employers to cover birth control in the health insurance plans for their employees. Under this new rule, hundreds of thousands of women would lose their ability to have their birth control costs covered for them.[85] The new rule would let insurers and employers refuse to provide birth control if doing so went against their "religious beliefs" or "moral convictions".[71][72] However, later in 2017 federal judge Wendy Beetlestone issued an injunction temporarily stopping the enforcement of this new rule.[71][72]

Push for possible over the counter policies

Some doctors and researchers, including the American Medical Association (AMA), would like the availability of the birth control pills to be extended to over the counter instead of prescription only status. They state that providing over the counter contraceptives could increase overall contraceptive accessibility for young women of color with low incomes, as they tend to have higher rates of unintended pregnancy. However, if the pill was to become over the counter, it would need to go through a rigorous check by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and be approved on the basis of safety, consistency, the ability of patients to properly take it without doctor guidance, and other factors. Although birth control pills have been deemed as relatively safe, there are some concerns about their side effects, such as a possible increased risk of vascular complications. Others, who are against making birth control pills available over the counter, have stated that the doctor appointments that go along with getting a prescription are important as they can provide information about contraceptive options as well as giving access to other reproductive health service such as sexually transmitted infection (STI) information and tests.[86]

Notable organizations

- Planned Parenthood Federation of America

- EngenderHealth

- Guttmacher Institute

- American Social Health Association

- Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States

Influence of religion

In 2014, the Supreme Court decided that for-profit corporations may offer insurance plans that do not cover contraception, by the rationale that the owners may hold that certain contraceptives violate their religious beliefs. This was a setback for the federal government's attempt to create a uniform set of health care insurance benefits.[87][88]

See also

- American family structure

- Abortion in the United States

- Birth control movement in the United States

- Women's rights

- Sex education in the United States

- HIV/AIDS in the United States

- History

- Demographic history of the United States

- Sex in the American Civil War

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Feminist Movement in the United States (1963-1982)

- Rush Limbaugh–Sandra Fluke controversy

References

- "Closely held" corporations are defined by the Internal Revenue Service as those which (a) have more than 50% of the value of their outstanding stock owned (directly or indirectly) by 5 or fewer individuals at any time during the last half of the tax year; and (b) are not personal service corporations. By this definition, approximately 90% of U.S. corporations are "closely held", and approximately 52% of the U.S. workforce is employed by "closely held" corporations. See Blake, Aaron (June 30, 2014). "A LOT of people could be affected by the Supreme Court's birth control decision – theoretically". The Washington Post.

Footnotes

- "Products – Data Briefs – Number 327 – December 2018". Cdc.gov. June 7, 2019. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- Engelman, pp. 3–4.

- Engelman, p. 5. Fertility rate dropped from 7 to 31⁄2 children per couple.

- Engelman, p. 11.

- Tone, pp. 73–75.

Engelman, pp. 11–12. - Engelman, pp. 5–6. Rarely in public: Engelman cites Brodie, Janet, Contraception and Abortion in 19th Century America, Cornell University Press, 1987.

- Engelman, p. 6.

Cullen DuPont, Kathryn (2000), "Contraception" in Encyclopedia of women's history in America, Infobase Publishing, p. 53 (first book in America).

Year of publication is variously stated as 1830 or 1831. - Engelman, p. 6.

- Engelman, pp. 6–7.

- Riddle, John M. (1999), Eve's Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West, Harvard University Press, pp. 226–7.

- Engelman, p. 7.

- Knowlton, Charles (October 1891) [1840]. Besant, Annie; Bradlaugh, Charles (eds.). Fruits of philosophy: a treatise on the population question. San Francisco: Reader's Library. OCLC 626706770. View original copy.

- Engelman, pp. 7–8.

- Engelman, pp. 8–9.

- Goldin, Claudia; Katz, Lawrence (2002). "The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women's Career and Marriage Decisions". Journal of Political Economy. 110 (4): 730–770. doi:10.1086/340778. ISSN 0022-3808. S2CID 221286686.

- "Contraception", in Women's studies encyclopedia, Volume 1, Helen Tierney (Ed.), Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999, p. 301.

- Engelman, pp. 9, 47.

- Ahluwalia, Sanjam (2008), Reproductive Restraints: Birth Control in India, 1877–1947, University of Illinois Press, p. 54.

- Tone, p. 17.

Engelman, pp. 13–14. - Engelman, pp. 13–14.

- Dennett p.30

- Engelman, p. 15.

- Engelman, pp. 15–16.

- Beisel, Nicola Kay (1998), Imperiled Innocents: Anthony Comstock and Family Reproduction in Victorian America, Princeton University Press, pp. 76–78.

- Engelman, p. 20.

- Engelman, pp. 18–19.

- CDC Bottom of this page https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/vsus.htm "Vital Statistics of the States, 2003, Volume I, Natality", Table 1-1 "Live births, birth rates, and fertility rates, by race: United States, 1909-2003."

- Engelman, p 186.

- Esser-Stuart, Joan E., "Margaret Higgins Sanger", in Encyclopedia of Social Welfare History in North America, Herrick, John and Stuart, Paul (Eds), SAGE, 2005, p. 323.

- Chesler, pp. 425–428.

- Tone, pp. 207–208, 265–266.

- Cook, Rebecca J.; Mahmoud F. Fathalla (September 1996). "Advancing Reproductive Rights Beyond Cairo and Beijing". International Family Planning Perspectives. 22 (3): 115–121. doi:10.2307/2950752. JSTOR 2950752. S2CID 147688303.

See also: Petchesky, Rosalind Pollack (2001), "Reproductive Politics", in The Oxford Companion to Politics of the World, Joël Krieger, Margaret E. Crahan (Eds.), Oxford University Press, pp. 726–727. - Tone, pp. 204–207.

Engelman, Peter, "McCormick, Katharine Dexter", in Encyclopedia of Birth Control, Vern L. Bullough (Ed.), ABC-CLIO, 2001, pp. 170–171.

Engelman, p. 182 (FDA approval). - "The Pill". Time. April 7, 1967. Archived from the original on February 19, 2005. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

Goldin, Claudia; Lawrence Katz (2002). "The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women's Career and Marriage Decisions". Journal of Political Economy. 110 (4): 730–770. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.473.6514. doi:10.1086/340778. S2CID 221286686. - Lynch, Catherine M. "History of the IUD". Contraception Online. Baylor College of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2006-01-27. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- "A Brief History of Birth Control". Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "William Baird makes history". Boston University News. April 12, 1967.

- "Birth Control 'Crusader' Arrested After BU Lecture". The Boston Herald. April 7, 1967.

- "Crusader Baird Faces 10-year Prison Term". Long Island Star Journal. September 11, 1967.

- "Baird Gets 3 Months For Birth Control Advice to Students". Boston Record American. May 20, 1969.

- "Publicity--Too Much?". Planned Parenthood News. Spring 1967.

- Engelman, p. 184.

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1972). Findlaw.com. Retrieved 26 January 2007.

- Office of Population Affairs Clearinghouse. "Fact Sheet: Title X Family Planning Program." Archived April 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine January 2008.

- "Facts on Publicly Funded Contraceptive Services in the United States". Guttmacher Institute. August 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- "Family Planning - Overview". Healthy People 2020. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 5 March 2012. The DHHS cites:

Gold RB, Sonfield A, Richards C, et al., Next steps for America's family planning program: Leveraging the potential of Medicaid and Title X in an evolving health care system, Guttmacher Institute, 2009; and

Frost J, Finer L, Tapales A., "The impact of publicly funded family planning clinic services on unintended pregnancies and government cost savings", J Health Care Poor Underserved, 2008 Aug, 19(3):778-96. - The drug is also known as RU-486 or Mifeprex.

Mifepristone is still used for contraception in Russia and China.

Ebadi, Manuchair, "Mifepristone" in Desk reference of clinical pharmacology, CRC Press, 2007, p. 443, ISBN 978-1-4200-4743-1.

Baulieu, Étienne-Émile; Rosenblum, Mort (1991). The "abortion pill" : RU-486, a woman's choice. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-73816-7.

Mifeprex prescribing information (label). Retrieved 24 January 2012.

Mifeprex (mifepristone) Information. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

FDA approval letter to Population Council. 28 September 2000. Retrieved 24 January 2012. - Kolata, Gina (September 29, 2000). "U.S. approves abortion pill; drug offers more privacy and could reshape debate". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- The FDA approved the Yuzpe regimen in 1997.

Levonorgestrel (Plan B) was approved, by prescription, in 1999.

Ebadi, Manuchair, "Levonorgestrel", in Desk Reference of Clinical Pharmacology, CRC Press, 2007, p. 338, ISBN 978-1-4200-4743-1.

Updated FDA Action on Plan B (levonorgestrel) Tablets Archived 2012-06-30 at the Wayback Machine (press release). 22 April 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

FDA Approves Over-the-Counter Access for Plan B for Women 18 and Older (press release). 24 August 2006. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

The phrase "morning after pill" is a misnomer, because it can be taken several days after unprotected sexual intercourse to have an effect to reduce the rates of an unplanned pregnancy. - The drug is known as ulipristal acetate or by the brand name ella.

Sankar, Nathan, Oxford Handbook of Genitourinary Medicine, HIV, and Sexual Health, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 386, ISBN 978-0-19-957166-6.

ella, ulipristal acetate. FDA Reproductive Health Drugs Advisory Committee report. 17 June 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

Prescribing information for ella. Retrieved 24 January 2012

FDA approves ella tablets for prescription emergency contraception Archived 2012-02-09 at the Wayback Machine (press release). 13 August 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2012. - Speroff, Leon (2010), A Clinical Guide for Contraception, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, ISBN 978-1-60831-610-6, pp. 153–155.

- Jackson, p. 89.

Gordon (2002), p. 336. - McBride, Dorothy (2008), Abortion in the United States: a Reference Handbook, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-098-8, pp. 67–68.

- "Commission Decision on Coverage of Contraception". The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. 2000-12-14. Archived from the original on 2017-12-07. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- "Contraceptive Coverage in the New Health Care Law: Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). 2011-11-01. Retrieved 2014-01-25. "The official start date is August 1, 2012, but since most plan changes take effect at the beginning of a new plan year, the requirements will be in effect for most plans on January 1, 2013. School health plans, which often begin their health plan years around the beginning of the school year, will see the benefits of the August 1st start date."

- "Prescription Drug Costs and Health Reform: FAQ". 2013-05-04. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- "Contraceptive Coverage in the New Health Care Law: Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). 2011-11-01. Retrieved 2014-01-25. "These changes include cutting benefits significantly; increasing co-insurance, co-payments, or deductibles or out-of-pocket limits by certain amounts; decreasing premium contributions by more than 5%; or adding or lowering annual limits."

- "Contraceptive Coverage in the New Health Care Law: Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). 2011-11-01. Retrieved 2014-01-25. "Non-grandfathered plans are group health plans created after the health care reform law was signed by the President or individual health plans purchased after that date."

- Sonfield, Adam (2013). "Implementing the Federal Contraceptive Coverage Guarantee: Progress and Prospects" (PDF). Guttmacher Policy Review. 16 (4). Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- "Little Sisters of the Poor Saints Peter and Paul Home v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the State of New Jersey" (PDF). Supreme Court.

- Willis, David (June 30, 2014). "Hobby Lobby case: Court curbs contraception mandate". BBC News. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- O'Donoghue, Amy Joi (Jul 5, 2014). "Group protests Hobby Lobby decision on birth control". Deseret News. Retrieved Jul 30, 2014.

- Haberkorn, Jennifer; Gerstein, Josh (Jun 30, 2014). "Supreme Court sides with Hobby Lobby on contraception mandate". Politico. Retrieved Jun 30, 2014.

- See:

- Wolf, Richard (June 30, 2014). "Justices rule for Hobby Lobby on contraception mandate". USA Today.

- Mears, Bill; Cohen, Tom (June 30, 2014). "Supreme Court rules against Obama in contraception case". CNN.

- Barrett, Paul (July 7, 2014). "A Supreme Feud Over Birth Control: Four Blunt Points". BusinessWeek.

- LoGiurato, Brett (July 3, 2014). "Female Justices Issue Scathing Dissent In The First Post-Hobby Lobby Birth Control Exemption". Business Insider.

- Liptak, Adam (March 23, 2016). "Justices Seem Split in Case on Birth Control Mandate". The New York Times.

- Zubik v. Burwell, No. 14–1418, 578 U.S. ___, slip op. at 3, 5 (2016) (per curiam).

- Zubik, slip op. at 3–4.

- Zubik, slip op. at 4.

- Zubik, slip op. at 2–3 (Sotomayor, J., concurring).

- "Trump rolls back free birth control". BBC News. 6 October 2017.

- "Federal judge in Pennsylvania temporarily blocks new Trump rules on birth control". Associated Press.

- Hatcher, Robert D. (2011). Contraceptive Technology (20th ed.). Ardent Media, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0.

- Guyot, Isabel V. Sawhill and Katherine (2019-06-24). "Preventing unplanned pregnancy: Lessons from the states". Brookings. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- Finocharo, Jane; Welti, Kate; Manlove, Jennifer (24 June 2021). "Two Thirds or Less of Black and Hispanic Women Rate Their Experiences with Family Planning Providers as "Excellent"". Child Trends. Retrieved 2021-06-27.

- James Trussell; Anjana Lalla; Quan Doan; Eileen Reyes; Lionel Pinto; Joseph Gricar (2009). "Cost effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States". Contraception. 79 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.003. PMC 3638200. PMID 19041435.

- "Products - Data Briefs - Number 388- October 2020". www.cdc.gov. 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2022-04-30.

- Commissioner, Office of the (2021-12-09). "Birth Control". FDA.

- "Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Adolescent Women's Sexual and Reproductive Behavior: The Case of Five Developed Countries". Guttmacher Institute. 2005-02-09. Retrieved 2022-04-30.

- Fikslin, Rachel A.; Goldberg, Alison J.; Gesselman, Amanda N.; Reinka, Mora A.; Pervez, Omaima; Franklin, Elissia T.; Ahn, Olivia; Price, Devon M. (2022-01-01). "Changes in Utilization of Birth Control and PrEP During COVID-19 in the USA: A Mixed-Method Analysis". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 51 (1): 365–381. doi:10.1007/s10508-021-02086-6. ISSN 1573-2800. PMC 8574936. PMID 34750774.

- Aly, Jasmine; Haeger, Kristin O.; Christy, Alicia Y.; Johnson, Amanda M. (2020-10-08). "Contraception access during the COVID-19 pandemic". Contraception and Reproductive Medicine. 5 (1): 17. doi:10.1186/s40834-020-00114-9. ISSN 2055-7426. PMC 7541094. PMID 33042573.

- Ullah, Md. Asad; Moin, Abu Tayab; Araf, Yusha; Bhuiyan, Atiqur Rahman; Griffiths, Mark D.; Gozal, David (2020-12-10). "Potential Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Future Birth Rate". Frontiers in Public Health. 8: 578438. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.578438. ISSN 2296-2565. PMC 7758229. PMID 33363080.

- The Editors (2013). "Contraception at Risk". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (1): 77–78. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1315461. PMID 24328442.

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - Kumar, Sheila V (12 June 2015). "Oregon women can get a year's supply of birth control". Pharmaceutical Processing. Associated Press.

- Pear, Robert; Ruiz, Rebecca R.; Goodstein, Laurie (2017-10-06). "Trump Administration Rolls Back Birth Control Mandate". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- "Moving Oral Contraceptives to Over-the-Counter Status: Policy Versus Politics" (PDF). Guttmacher Policy Review.

- Hamel, Mary Beth; Annas, George J.; Ruger, Theodore W.; Ruger, Jennifer Prah (2014). "Money, Sex, and Religion — The Supreme Court's ACA Sequel". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (9): 862–866. doi:10.1056/NEJMhle1408081. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 25029337.

- Cohen, I. Glenn; Lynch, Holly Fernandez; Curfman, Gregory D. (2014). "When Religious Freedom Clashes with Access to Care". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (7): 596–599. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1407965. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 24988298.

Sources

- Baker, Jean H. (2011), Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-8090-9498-1.

- Buchanan, Paul D. (2009), American Women's Rights Movement: A Chronology of Events and of Opportunities from 1600 to 2008, Branden Books, ISBN 978-0-8283-2160-0.

- Chesler, Ellen (1992), Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-60088-5.

- Cox, Vicki (2004), Margaret Sanger: Rebel For Women's Rights, Chelsea House Publications, ISBN 0-7910-8030-7.

- Dennett, Mary (1926), Birth Control Laws: Shall We Keep Them, Abolish Them, or Change Them?, Frederick H. Hitchcock.

- Engelman, Peter C. (2011), A History of the Birth Control Movement in America, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-0-313-36509-6.

- Gordon, Linda (1976), Woman's Body, Woman's Right: A Social History of Birth Control in America, Grossman Publishers, ISBN 978-0-670-77817-1.

- Gordon, Linda (2002), The Moral Property of Women: a History of Birth Control Politics in America, University of Illinois Press, ISBN 978-0-252-02764-2.

- Hajo, Cathy Moran (2010), Birth Control on Main Street: Organizing Clinics in the United States, 1916–1939, University of Illinois Press, ISBN 978-0-252-03536-4.

- Jackson, Emily (2001), Regulating reproduction: law, technology and autonomy, Hart Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84113-301-0.

- Kennedy, David (1970), Birth Control in America: The Career of Margaret Sanger, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-01495-2.

- McCann, Carole Ruth (1994), Birth Control Politics in the United States, 1916–1945 , Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-8612-8.

- McCann, Carole Ruth (2010), "Women as Leaders in the Contraceptive Movement", in Gender and Women's Leadership: A Reference Handbook, Karen O'Connor (Ed), SAGE, ISBN 978-1-4129-6083-0.

- National Research Council (US) Committee on Population. Contraception and Reproduction: Health Consequences for Women and Children in the Developing World. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1989. 4, Contraceptive Benefits and Risks. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235069/

- Tone, Andrea (2002), Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America, Hill and Wang, ISBN 978-0-8090-3816-9.

Further reading

- Bailey, Martha J.; Lindo, Jason M. (2017). "Access and Use of Contraception and Its Effects on Women's Outcomes in the U.S." (PDF). NBER Working Paper No. 23465. doi:10.3386/w23465. S2CID 80536529.

- Coates, Patricia Walsh (2008), Margaret Sanger and the Origin of the Birth Control Movement, 1910–1930: The Concept of Women's Sexual Autonomy, Edwin Mellen Press, ISBN 978-0-7734-5099-8.

- Goldman, Emma (1931), Living My Life, Knopf, ISBN 978-0-87905-096-2 (1982 reprint).

- Rosen, Robyn L. (2003), Reproductive Health, Reproductive Rights: Reformers and the Politics of Maternal Welfare, 1917–1940, Ohio State University Press, ISBN 978-0-8142-0920-2.

- Sanger, Margaret (1938), An Autobiography, Cooper Square Press, ISBN 0-8154-1015-8.