Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) is an acquired autoimmune disease of the peripheral nervous system characterized by progressive weakness and impaired sensory function in the legs and arms.[1] The disorder is sometimes called chronic relapsing polyneuropathy (CRP) or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (because it involves the nerve roots).[2] CIDP is closely related to Guillain–Barré syndrome and it is considered the chronic counterpart of that acute disease.[3] Its symptoms are also similar to progressive inflammatory neuropathy. It is one of several types of neuropathy.

| Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | CIDP, chronic relapsing polyneuropathy, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy |

| |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Types

Several variants have been reported. Specially important are:

- An asymmetrical variant of CIDP is known as Lewis-Sumner Syndrome.[4] or MADSAM (multifocal acquired demyelinating sensory and motor neuropathy)[5]

- A variant with CNS involvement named combined central and peripheral demyelination (CCPD)[6]

Currently there is one special variant in which the CNS is also affected. It is termed "combined central and peripheral demyelination" (CCPD) and is special because it belongs at the same time to the CDIP syndrome and to the multiple sclerosis spectrum.[6] These cases seem to be related to the presence of anti-neurofascin autoantibodies.

Causes

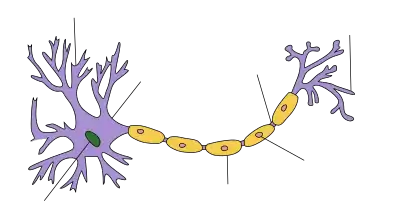

| Neuron |

|---|

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (or polyradiculoneuropathy) is considered an autoimmune disorder destroying myelin, the protective covering of the nerves. Typical early symptoms are "tingling" (sort of electrified vibration or paresthesia) or numbness in the extremities, frequent (night) leg cramps, loss of reflexes (in knees), muscle fasciculations, "vibration" feelings, loss of balance, general muscle cramping and nerve pain.[7][8] CIDP is extremely rare but under-recognized and under-treated due to its heterogeneous presentation (both clinical and electrophysiological) and the limitations of clinical, serologic, and electrophysiologic diagnostic criteria. Despite these limitations, early diagnosis and treatment is favoured in preventing irreversible axonal loss and improving functional recovery.[9]

There is a lack of awareness and treatment of CIDP. Although there are stringent research criteria for selecting patients for clinical trials, there are no generally agreed-upon clinical diagnostic criteria for CIDP due to its different presentations in symptoms and objective data. Application of the present research criteria to routine clinical practice often misses the diagnosis in a majority of patients, and patients are often left untreated despite progression of their disease.[10]

CIDP has been associated with diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, and paraproteinemias.

Variants with paranodal autoantibodies

Some variants of CIDP present autoimmunity against proteins of the node of Ranvier. These variants comprise a subgroup of inflammatory neuropathies with IgG4 autoantibodies against the paranodal proteins neurofascin-155, contactin-1 and caspr-1.[11]

These cases are special not only because of their pathology, but also because they are non-responsive to the standard treatment. They are responsive to Rituximab instead.[11]

Also some cases of combined central and peripheral demyelination (CCPD) could be produced by neurofascins.[12]

Autoantibodies of the IgG3 Subclass in CIDP

Autoantibodies to components of the Ranvier nodes, specially autoantibodies the Contactin-associated protein 1 (CASPR), cause a form of CIDP with an acute "Guillain-Barre-like" phase, followed by a chronic phase with progressive symptoms. Different IgG subclasses are associated with the different phases of the disease. IgG3 Caspr autoantibodies were found during the acute GBS-like phase, while IgG4 Caspr autoantibodies were present during the chronic phase of disease.[13]

Diagnosis and symptoms

Diagnosis is typically made on the basis of presenting symptoms in tandem with electrodiagnostic testing or a nerve biopsy. Doctors may use a lumbar puncture to verify the presence of increased cerebrospinal fluid protein.

Differential diagnosis

CIBP variants are among several types of immune-mediated neuropathies recognised.[14][15] These include:

- Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) with subtypes:

- Classical CIDP

- CIDP with diabetes

- CIDP/monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance

- Sensory CIDP

- Multifocal motor neuropathy

- Multifocal acquired demyelinating sensory and motor neuropathy (Lewis-Sumner syndrome)

- Multifocal acquired sensory and motor neuropathy

- Distal acquired demyelinating sensory neuropathy

- Guillain–Barré syndrome with subtypes:

- Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy

- Acute motor axonal neuropathy

- Acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy

- Acute pandysautonomia

- Miller Fisher syndrome

- IgM monoclonal gammopathies with subtypes:

- Waldenström's macroglobulinemia

- Mixed cryoglobulinemia, gait ataxia, late-onset polyneuropathy syndrome

- Myelin-associated glycoprotein-associated gammopathy, polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M-protein and skin changes syndrome (POEMS)

Other possible diagnoses are

For this reason a diagnosis of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy needs further investigations. The diagnosis is usually provisionally made through a clinical neurological examination.

Symptoms

Symptoms such as diminished or absent deep-tendon reflexes and sensory ataxia are common. Other symptoms include proximal and distal muscle weakness in the limbs.

Patients usually present with a history of weakness, numbness, tingling, pain and difficulty in walking. They may additionally present with fainting spells while standing up or burning pain in extremities. Some patients may have sudden onset of back pain or neck pain radiating down the extremities, usually diagnosed as radicular pain. These symptoms are usually progressive and may be intermittent.

Autonomic system dysfunction can occur; in such a case, the patient would complain of orthostatic dizziness, problems breathing, eye, bowel, bladder and cardiac problems. The patient may also present with a single cranial nerve or peripheral nerve dysfunction.

On examination the patients may have weakness, and loss of deep tendon reflexes (rarely increased or normal). There may be atrophy (shrinkage) of muscles, fasciculations (twitching) and loss of sensation. Patients may have multi-focal motor neuropathy, as they have no sensory loss.

Most experts consider the necessary duration of symptoms to be greater than 8 weeks for the diagnosis of CIDP to be made.

Fatigue has been identified as common in CIDP patients, but it is unclear how much this is due to primary (due to the disease action on the body) or secondary effects (impacts on the whole person of being ill with CIDP).[16][17][18]

Tests

Typical diagnostic tests include:

- Electrodiagnostics – electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction study (NCS). In usual CIDP, the nerve conduction studies show demyelination. These findings include:

- a reduction in nerve conduction velocities;

- the presence of conduction block or abnormal temporal dispersion in at least one motor nerve;

- prolonged distal latencies in at least two nerves;

- absent F waves or prolonged minimum F wave latencies in at least two motor nerves. (In some case EMG/NCV can be normal).

- Serum test to exclude other autoimmune diseases.

- Lumbar puncture and serum test for anti-ganglioside antibodies. These antibodies are present in the branch of CIDP diseases comprised by anti-GM1, anti-GD1a, and anti-GQ1b.

- Sural nerve biopsy; biopsy is considered for those patients in whom the diagnosis is not completely clear, when other causes of neuropathy (e.g., hereditary, vasculitic) cannot be excluded, or when profound axonal involvement is observed on EMG.

- Ultrasound of the peripheral nerves may show swelling of the affected nerves.[19][20][21]

- Magnetic resonance imaging can also be used in the diagnostic workup.[22][23]

In some cases electrophysiological studies fail to show any evidence of demyelination. Though conventional electrophysiological diagnostic criteria are not met, the patient may still respond to immunomodulatory treatments. In such cases, presence of clinical characteristics suggestive of CIDP are critical, justifying full investigations, including sural nerve biopsy.[24]

Treatment

First-line treatment for CIDP is currently intravenous immunoglobulin and other treatments include corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone), and plasmapheresis (plasma exchange) which may be prescribed alone or in combination with an immunosuppressant drug.[25] Recent controlled studies show subcutaneous immunoglobulin appears to be as effective for CIDP treatment as intravenous immunoglobulin in most patients, and with fewer systemic side effects.[26]

Intravenous immunoglobulin and plasmapheresis have proven benefit in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Despite less definitive published evidence of efficacy, corticosteroids are considered standard therapies because of their long history of use and cost effectiveness. Intravenous immunoglobulin is probably the first-line CIDP treatment, but is extremely expensive. For example, in the U.S., a single 65 g dose of Gamunex brand in 2010 might be billed at the rate of $8,000 just for the immunoglobulin—not including other charges such as nurse administration.

Immunosuppressive drugs are often of the cytotoxic (chemotherapy) class, including rituximab (Rituxan) which targets B cells, and cyclophosphamide, a drug which reduces the function of the immune system. Ciclosporin has also been used in CIDP but with less frequency as it is a newer approach.[27] Ciclosporin is thought to bind to immunocompetent lymphocytes, especially T-lymphocytes.

Non-cytotoxic immunosuppressive treatments usually include the anti-rejection transplant drugs azathioprine (Imuran/Azoran) and mycophenolate mofetil (Cellcept). In the U.S., these drugs are used "off-label", meaning that they do not have an indication for the treatment of CIDP in their package inserts. Before azathioprine is used, the patient should first have a blood test that ensures that azathioprine can safely be used.

Anti-thymocyte globulin, an immunosuppressive agent that selectively destroys T lymphocytes is being studied for use in CIDP. Anti-thymocyte globulin is the gamma globulin fraction of antiserum from animals that have been immunized against human thymocytes. It is a polyclonal antibody. Although chemotherapeutic and immunosuppressive agents have shown to be effective in treating CIDP, significant evidence is lacking, mostly due to the heterogeneous nature of the disease in the patient population in addition to the lack of controlled trials.

A review of several treatments found that azathioprine, interferon alpha and methotrexate were not effective.[28] Cyclophosphamide and rituximab seem to have some response. Mycophenolate mofetil may be of use in milder cases. Immunoglobulin and steroids are the first line choices for treatment.

In severe cases of CIDP, when second-line immunomodulatory drugs are not efficient, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is sometimes performed. The treatment may induce long-term remission even in severe treatment-refractory cases of CIDP. To improve outcome, it has been suggested that it should be initiated before irreversible axonal damage has occurred. However, a precise estimation of its clinical efficacy for CIDP is not available, as randomized controlled trials have not been performed.[29]

Physical therapy and occupational therapy may improve muscle strength, activities of daily living, mobility, and minimize the shrinkage of muscles and tendons and distortions of the joints.

Prognosis

As in multiple sclerosis, another demyelinating condition, it is not possible to predict with certainty how CIDP will affect patients over time. The pattern of relapses and remissions varies greatly with each patient. A period of relapse can be very disturbing, but many patients make significant recoveries.

If diagnosed early, initiation of early treatment to prevent loss of nerve axons is recommended. However, many individuals are left with residual numbness, weakness, tremors, fatigue and other symptoms which can lead to long-term morbidity and diminished quality of life.[2]

It is important to build a good relationship with doctors, both primary care and specialist. Because of the rarity of the illness, many doctors will not have encountered it before. Each case of CIDP is different, and relapses, if they occur, may bring new symptoms and problems. Because of the variability in severity and progression of the disease, doctors will not be able to give a definite prognosis. A period of experimentation with different treatment regimens is likely to be necessary in order to discover the most appropriate treatment regimen for a given patient.

Epidemiology

In 1982 Lewis et al. reported a group of patients with a chronic asymmetrical sensorimotor neuropathy mostly affecting the arms with multifocal involvement of peripheral nerves.[30] Also in 1982 Dyck et al reported a response to prednisolone to a condition they referred to as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy.[31] Parry and Clarke in 1988 described a neuropathy which was later found to be associated with IgM autoantibodies directed against GM1 gangliosides.[32][33] This latter condition was later termed multifocal motor neuropathy[34] This distinction is important because multifocal motor neuropathy responds to intravenous immunoglobulin alone, while chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy responds to intravenous immunoglobulin, steroids and plasma exchange.[35] It has been suggested that multifocal motor neuropathy is distinct from chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and that Lewis-Sumner syndrome is a distinct variant type of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy.[36]

The Lewis-Sumner form of this condition is considered a rare disease with only 50 cases reported up to 2004.[37] A total of 90 cases had been reported by 2009.[38]

Vaccine injury compensation for CIDP

The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program has awarded money damages to patients who came down with CIDP after receiving one of the childhood vaccines listed on the Federal Government's vaccine injury table. These Vaccine Court awards often come with language stating that the Court denies that the specific vaccine "caused petitioner to suffer CIDP or any other injury. Nevertheless, the parties agree to the joint stipulation, attached hereto as Appendix A. The undersigned finds said stipulation reasonable and adopts it as the decision of the Court in awarding damages, on the terms set forth therein."[39] A keyword search on the Court of Federal Claims "Opinions/Orders" database for the term "CIDP" returns 202 opinions related to CIDP and vaccine injury compensation.[40]

See also

References

- "Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy (CIDP) Information Page". ninds.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- Kissel JT (2003). "The treatment of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy". Seminars in Neurology. 23 (2): 169–80. doi:10.1055/s-2003-41130. PMID 12894382.

- "GBS (Guillain-Barré Syndrome) - CIDP Neuropathy". cidpneuropathysupport.com. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- "Lewis summer syndrome GUIDE".

- "Lewis-Sumner syndrome".

- Kira, Jun-ichi; Yamasaki, Ryo; Ogata, Hidenori (November 2019). "Anti-neurofascin autoantibody and demyelination". Neurochemistry International. 130: 104360. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2018.12.011. PMID 30582947. S2CID 56595020.

- "C.I.D.P. Log". cidplog.com. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- Latov, Norman (2014-07-01). "Diagnosis and treatment of chronic acquired demyelinating polyneuropathies". Nature Reviews Neurology. 10 (8): 435–446. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.117. PMID 24980070. S2CID 23639113.

- Toothaker TB, Brannagan TH (2007). "Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathies: current treatment strategies". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 7 (1): 63–70. doi:10.1007/s11910-007-0023-5. PMID 17217856. S2CID 46426663.

- Latov, Norman (2002). "Diagnosis of CIDP". Neurology. 59 (12 Suppl 6): S2–6. doi:10.1212/wnl.59.12_suppl_6.s2. PMID 12499464. S2CID 25742148.

- Doppler, Kathrin; Sommer, Claudia (March 2017). "The New Entity of Paranodopathies: A Target Structure with Therapeutic Consequences". Neurology International Open. 01 (1): E56–E60. doi:10.1055/s-0043-102455.

- Ciron, Jonathan; Carra-Dallière, Clarisse; Ayrignac, Xavier; Neau, Jean-Philippe; Maubeuge, Nicolas; Labauge, Pierre (January 2019). "The coexistence of recurrent cerebral tumefactive demyelinating lesions with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis and demyelinating neuropathy". Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 27: 223–225. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2018.11.002. PMID 30414563. S2CID 53292167.

- Hampe, Christiane S. (2019). "Significance of Autoantibodies". Neuroimmune Diseases. Contemporary Clinical Neuroscience. pp. 109–142. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-19515-1_4. ISBN 978-3-030-19514-4. S2CID 201980461.

- Finsterer, J. (August 2005). "Treatment of immune-mediated, dysimmune neuropathies". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 112 (2): 115–125. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00448.x. PMID 16008538. S2CID 10651959.

- Ensrud, Erik R.; Krivickas, Lisa S. (May 2001). "Acquired Inflammatory Demyelinating Neuropathies". Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 12 (2): 321–334. doi:10.1016/S1047-9651(18)30072-X. PMID 11345010.

- Gable, Karissa L.; Attarian, Hrayr; Allen, Jeffrey A. (December 2020). "Fatigue in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy". Muscle & Nerve. 62 (6): 673–680. doi:10.1002/mus.27038. PMID 32710648. S2CID 225480334.

- Boukhris, Sami; Magy, Laurent; Gallouedec, Gael; Khalil, Mohamed; Couratier, Philippe; Gil, Juan; Vallat, Jean-Michel (September 2005). "Fatigue as the main presenting symptom of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: a study of 11 cases". Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System. 10 (3): 329–337. doi:10.1111/j.1085-9489.2005.10311.x. PMID 16221292. S2CID 24896124.

- Merkies, Ingemar S. J.; Kieseier, Bernd C. (2016). "Fatigue, Pain, Anxiety and Depression in Guillain-Barré Syndrome and Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy". European Neurology. 75 (3–4): 199–206. doi:10.1159/000445347. PMID 27077919. S2CID 9884101.

- Herraets, Ingrid J.T.; Goedee, H. Stephan; Telleman, Johan A.; van Asseldonk, Jan-Thies H.; Visser, Leo H.; van der Pol, W. Ludo; van den Berg, Leonard H. (January 2018). "High-resolution ultrasound in patients with Wartenberg's migrant sensory neuritis, a case-control study". Clinical Neurophysiology. 129 (1): 232–237. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2017.10.040. PMID 29202391. S2CID 24416887.

- Goedee, H. Stephan; van der Pol, W. Ludo; van Asseldonk, Jan-Thies H.; Franssen, Hessel; Notermans, Nicolette C.; Vrancken, Alexander J.F.E.; van Es, Michael A.; Nikolakopoulos, Stavros; Visser, Leo H.; van den Berg, Leonard H. (10 January 2017). "Diagnostic value of sonography in treatment-naive chronic inflammatory neuropathies". Neurology. 88 (2): 143–151. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000003483. PMID 27927940. S2CID 5466514.

- Décard, Bernhard F.; Pham, Mirko; Grimm, Alexander (January 2018). "Ultrasound and MRI of nerves for monitoring disease activity and treatment effects in chronic dysimmune neuropathies – Current concepts and future directions". Clinical Neurophysiology. 129 (1): 155–167. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2017.10.028. PMID 29190522. S2CID 37585666.

- Shibuya, Kazumoto; Sugiyama, Atsuhiko; Ito, Sho-ichi; Misawa, Sonoko; Sekiguchi, Yukari; Mitsuma, Satsuki; Iwai, Yuta; Watanabe, Keisuke; Shimada, Hitoshi; Kawaguchi, Hiroshi; Suhara, Tetsuya; Yokota, Hajime; Matsumoto, Hiroshi; Kuwabara, Satoshi (February 2015). "Reconstruction magnetic resonance neurography in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: MR Neurography in CIDP". Annals of Neurology. 77 (2): 333–337. doi:10.1002/ana.24314. PMID 25425460. S2CID 39436370.

- Rajabally, Yusuf A.; Knopp, Michael J.; Martin-Lamb, Darren; Morlese, John (July 2014). "Diagnostic value of MR imaging in the Lewis–Sumner syndrome: A case series". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 342 (1–2): 182–185. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2014.04.033. PMID 24825730. S2CID 44981467.

- Azulay JP (2006). "[The diagnosis of chronic axonal polyneuropathy: the poorly understood chronic polyradiculoneuritides]". Revue Neurologique (Paris) (in French). 162 (12): 1292–5. doi:10.1016/S0035-3787(06)75150-5. PMID 17151528.

- Hughes RA (2002). "Systematic reviews of treatment for inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy". Journal of Anatomy. 200 (4): 331–9. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00041.x. PMC 1570692. PMID 12090400.

- Hadden, Robert D. M.; Marreno, Fabrizio (2016-12-28). "Switch from intravenous to subcutaneous immunoglobulin in CIDP and MMN: improved tolerability and patient satisfaction". Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders. 8 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1177/1756285614563056. ISSN 1756-2856. PMC 4286942. PMID 25584070.

- Odaka M, Tatsumoto M, Susuki K, Hirata K, Yuki N (2005). "Intractable chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy treated successfully with ciclosporin". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 76 (8): 1115–20. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.035428. PMC 1739743. PMID 16024890.

- Rajabally, Yusuf A. (2017). "Unconventional treatments for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy". Neurodegenerative Disease Management. 7 (5): 331–342. doi:10.2217/nmt-2017-0017. PMID 29043889.

- Burman, Joachim; Tolf, Andreas; Hägglund, Hans; Askmark, Håkan (2018-02-01). "Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for neurological diseases". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 89 (2): 147–155. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2017-316271. ISSN 0022-3050. PMC 5800332. PMID 28866625.

- Lewis, RA; Sumner, AJ; Brown, MJ; Asbury, AK (September 1982). "Multifocal demyelinating neuropathy with persistent conduction block". Neurology. 32 (9): 958–64. doi:10.1212/wnl.32.9.958. PMID 7202168. S2CID 40027684.

- Dyck, Peter James; O'Brien, Peter C.; Oviatt, Karen F.; Dinapoli, Robert P.; Daube, Jasper R.; Bartleson, John D.; Mokri, Bahram; Swift, Thomas; Low, Phillip A.; Windebank, Anthony J. (February 1982). "Prednisone improves chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy more than no treatment". Annals of Neurology. 11 (2): 136–141. doi:10.1002/ana.410110205. PMID 7041788. S2CID 24567176.

- Parry, Gareth J.; Clarke, Stephen (February 1988). "Multifocal acquired demyelinating neuropathy masqurading as motor neuron disease". Muscle & Nerve. 11 (2): 103–107. doi:10.1002/mus.880110203. PMID 3343985. S2CID 21481288.

- Pestronk, A; Cornblath, DR; Ilyas, AA; Baba, H; Quarles, RH; Griffin, JW; Alderson, K; Adams, RN (July 1988). "A treatable multifocal motor neuropathy with antibodies to GM1 ganglioside". Annals of Neurology. 24 (1): 73–8. doi:10.1002/ana.410240113. PMID 2843079. S2CID 44845902.

- Nobile-Orazio, Eduardo (April 2001). "Multifocal motor neuropathy". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 115 (1–2): 4–18. doi:10.1016/S0165-5728(01)00266-1. PMC 1073940. PMID 11282149.

- van Doorn, Pieter A.; Garssen, Marcel P.J. (October 2002). "Treatment of immune neuropathies". Current Opinion in Neurology. 15 (5): 623–631. doi:10.1097/00019052-200210000-00014. PMID 12352007. S2CID 29950514.

- Lewis, Richard Alan (October 2007). "Neuropathies associated with conduction block". Current Opinion in Neurology. 20 (5): 525–530. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282efa143. PMID 17885439. S2CID 32166227.

- Viala, K; Renié, L; Maisonobe, T; Béhin, A; Neil, J; Léger, JM; Bouche, P (September 2004). "Follow-up study and response to treatment in 23 patients with Lewis-Sumner syndrome". Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 127 (Pt 9): 2010–7. doi:10.1093/brain/awh222. PMID 15289267.

- Rajabally, Yusuf A.; Chavada, Govindsinh (February 2009). "Lewis-sumner syndrome of pure upper-limb onset: Diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic features". Muscle & Nerve. 39 (2): 206–220. doi:10.1002/mus.21199. PMID 19145651. S2CID 43478826.

- "Riley v. Secretary of Health and Human Services, Case No. 16-262V". United States Court of Federal Claims. July 30, 2019.

- "United States Court of Federal Claims Opinions/Orders". United States Court of Federal Claims. October 24, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.