Caffeine dependence

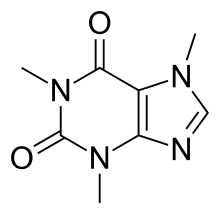

Caffeine dependence is the condition of having a substance dependence on caffeine, a commonplace central nervous system stimulant drug which occurs in nature in coffee, tea, yerba mate, cocoa, and other plants. Caffeine is also an additive in many consumer products, including beverages such as caffeinated alcoholic beverages, energy drinks, and colas.

| Caffeine dependence | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Caffeine addiction |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Caffeine's mechanism of action is somewhat different from that of cocaine and the substituted amphetamines; caffeine blocks adenosine receptors A1 and A2A.[1] Adenosine is a by-product of cellular activity, and stimulation of adenosine receptors produces feelings of tiredness and the need to sleep. Caffeine's ability to block these receptors means the levels of the body's natural stimulants, dopamine and norepinephrine, continue at higher levels.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders describes four caffeine-related disorders including intoxication, withdrawal, anxiety, and sleep.[2]

Dependence

Mild physical dependence can result from long-term caffeine use.[3] Caffeine addiction, or a pathological and compulsive form of use, has been documented in humans.[3][4]

Addiction vs. Dependence

Caffeine use is classified as a dependence, not an addiction. For a drug to be considered addictive, it must activate the brain's reward circuit. Caffeine, like addictive drugs, enhances dopamine signaling in the brain (is eugeroic), but not enough to activate the brain's reward circuit like addictive substances such as cocaine, morphine, and nicotine.[5] Caffeine dependence forms due to caffeine antagonizing the adenosine A2A receptor,[6] effectively blocking adenosine from the adenosine receptor site. This delays the onset of drowsiness and releases dopamine.[7]

Studies have demonstrated that people who take in a minimum of 100 mg of caffeine per day (about the amount in one cup of coffee) can acquire a physical dependence that would trigger withdrawal symptoms that include headaches, muscle pain and stiffness, lethargy, nausea, vomiting, depressed mood, and marked irritability.[8] Professor Roland R. Griffiths, a professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore strongly believes that caffeine withdrawal should be classified as a psychological disorder.[8] His research suggested that withdrawal affects 50% of habitual coffee drinkers, beginning within 12–24 hours after cessation of caffeine intake, and peaking in 20–48 hours, lasting as long as 9 days.[4][9]

Continued exposure to caffeine leads the body to create more adenosine-receptors in the central nervous system, which makes it more sensitive to the effects of adenosine. It reduces the stimulatory effects of caffeine by increasing tolerance, and it increases the withdrawal symptoms of caffeine as the body becomes more sensitive to the effects of adenosine once caffeine intake decreases. Caffeine tolerance develops very quickly. Tolerance to the sleep disruption effects of caffeine were seen after consumption of 400 mg of caffeine 3 times a day for 7 days, whereas complete tolerance was observed after consumption of 300 mg taken 3 times a day for 18 days.[10]

Physiological effects

When a person becomes caffeine dependent, it can cause a person to suffer different physiological effects which could lead to withdrawal. Symptoms can range from mild to severe that are dependent on the amount of caffeine consumed daily.[11][12] Tests are still being done to get a better understanding of the effects that occur to someone when they become dependent on different forms of caffeine to make it through the day.

Adults

Caffeine is consumed by many each day and from this a dependence is formed. For the most part caffeine consumption is safe, but consuming over 400 mg of caffeine has shown adverse physiological and psychological effects; especially in people that have pre-existing conditions.[13] When adults form a dependence on caffeine, it can cause a range of health problems such as headaches, insomnia, dizziness, cardiac issues, hypertension and others. When an adult is dependent on this substance, they must consume a certain amount of caffeine every day to avoid these effects.[13]

Pregnancy

If pregnant, it is recommended not to consume over 200 mg of caffeine a day (depending on size of person).[14] If a pregnant female consumes high levels of caffeine, it can result in low birth weights due to loss of blood flow to the placenta[15] which could lead to an increase in health problems later in that child's life.[16] It can also result in premature labor, reduced fertility, and other reproductive issues. If a female is dependent on an excessive amount of caffeine to get them through the day, it is recommended to talk to their healthcare provider to either eliminate the dependency of caffeine or to become less dependent on it.[17]

Children and Teenagers

It is not recommended for children under the age of 18 to consume several caffeinated drinks according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). If they were to consume caffeine it is recommended to follow some guidelines so they do not consume too much throughout the day.[18] If they do not follow, they can become dependent on caffeine and without it can suffer many different side effects. These include increase of heart rate and blood pressure, sleep disturbance, mood swings, and acidic problems. Long lasting problems on children's nervous system and cardiovascular system are currently unknown and studies are still being conducted on it.[19]

Tolerance

Tolerance levels regarding caffeine typically vary from person to person. Caffeine tolerance occurs when the stimulatory effects of caffeine decrease over time due to regular consumption. According to H.P. Ammon from the National Library of Medicine, caffeine tolerance occurs when the body responds to an intake of caffeine through the up-regulation of adenosine-receptors.[20]

References

- Fisone, G, Borgkvist A, Usiello A (2004): Caffeine as a psychomotor stimulant: Mechanism of Action. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 61:857-872

- Addicott, Merideth A. (2014). "Caffeine Use Disorder: A Review of the Evidence and Future Implications". Current Addiction Reports. 1 (3): 186–192. doi:10.1007/s40429-014-0024-9. PMC 4115451. PMID 25089257.

- Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 375. ISBN 9780071481274.

Long-term caffeine use can lead to mild physical dependence. A withdrawal syndrome characterized by drowsiness, irritability, and headache typically lasts no longer than a day. True compulsive use of caffeine has been documented.

- Hall, Harriet (5 February 2019). "Caffeine Withdrawal Headaches". Science-Based Medicine. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- Volkow, N D; Wang, G-J; Logan, J; Alexoff, D; Fowler, J S; Thanos, P K; Wong, C; Casado, V; Ferre, S; Tomasi, D (April 2015). "Caffeine increases striatal dopamine D2/D3 receptor availability in the human brain". Translational Psychiatry. 5 (4): e549–. doi:10.1038/tp.2015.46. PMC 4462609. PMID 25871974.

- Froestl, Wolfgang; Muhs, Andreas; Pfeifer, Andrea (14 November 2012). "Cognitive Enhancers (Nootropics). Part 1: Drugs Interacting with Receptors". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 32 (4): 793–887. doi:10.3233/JAD-2012-121186. PMID 22886028. S2CID 10511507.

- Ferré, Sergi (2016). "Mechanisms of the psychostimulant effects of caffeine: Implications for substance use disorders". Psychopharmacology. 233 (10): 1963–1979. doi:10.1007/s00213-016-4212-2. PMC 4846529. PMID 26786412.

- Studeville, George (January 15, 2010). "Caffeine Addiction Is a Mental Disorder, Doctors Say". National Geographic.

- Juliano, L. M.; Griffiths, R. R. (2004). "A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: Empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features". Psychopharmacology. 176 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-2000-x. PMID 15448977. S2CID 5572188.

- "Caffeine Pharmacology". News Medical. 28 February 2010.

- Meredith, Steven E.; Juliano, Laura M.; Hughes, John R.; Griffiths, Roland R. (September 2013). "Caffeine Use Disorder: A Comprehensive Review and Research Agenda". Journal of Caffeine Research. 3 (3): 114–130. doi:10.1089/jcr.2013.0016. ISSN 2156-5783. PMC 3777290. PMID 24761279.

- "Caffeine Calculator". Roaster Coffees. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- "Caffeine". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (August 2010). "ACOG CommitteeOpinion No. 462: Moderate caffeine consumption during pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 116 (2 Pt 1): 467–8. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb2a1. PMID 20664420.

- Sajadi-Ernazarova, Karima R.; Anderson, Jackie; Dhakal, Aayush; Hamilton, Richard J. (2020), "Caffeine Withdrawal", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613541, retrieved 2020-11-06

- "Should I limit caffeine during pregnancy?". nhs.uk. 2018-06-27. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- "Caffeine Intake During Pregnancy". American Pregnancy Association. 2016-04-27. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- Branum, Amy M.; Rossen, Lauren M.; Schoendorf, Kenneth C. (March 1, 2014). "Trends in Caffeine Intake Among US Children and Adolescents". Pediatrics. 133 (3): 386–393. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2877. ISSN 0031-4005. PMC 4736736. PMID 24515508.

- McVay, Ellen (February 19, 2020). "Is Coffee Bad For Kids?". Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- Ammon HP. Biochemical mechanism of caffeine tolerance. Arch Pharm (Weinheim). 1991 May;324(5):261-7. doi:10.1002/ardp.19913240502. PMID 1888264.