Hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below 35.0 °C (95.0 °F) in humans.[2] Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases.[3] In severe hypothermia, there may be hallucinations and paradoxical undressing, in which a person removes their clothing, as well as an increased risk of the heart stopping.[2]

| Hypothermia | |

|---|---|

| |

| During Napoleon Bonaparte's retreat from Russia in the winter of 1812, many troops died from hypothermia.[1] | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine |

| Symptoms |

|

| Complications | Afterdrop |

| Duration | Until the body temperature is raised to near-normal levels |

| Types |

|

| Causes | Mainly exposure to cold weather and cold water immersion |

| Risk factors | Alcohol intoxication, homelessness, low blood sugar, anorexia, advanced age[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms or body temperature below 35.0 °C (95.0 °F)[2] |

| Prevention | Wearing adequate clothes for weather, staying warm |

| Treatment |

|

| Medication | Sugar |

| Deaths | 1,500 per year (US)[2] |

Hypothermia has two main types of causes. It classically occurs from exposure to cold weather and cold water immersion. It may also occur from any condition that decreases heat production or increases heat loss.[1] Commonly, this includes alcohol intoxication but may also include low blood sugar, anorexia and advanced age.[2][1] Body temperature is usually maintained near a constant level of 36.5–37.5 °C (97.7–99.5 °F) through thermoregulation.[2] Efforts to increase body temperature involve shivering, increased voluntary activity, and putting on warmer clothing.[2][4] Hypothermia may be diagnosed based on either a person's symptoms in the presence of risk factors or by measuring a person's core temperature.[2]

The treatment of mild hypothermia involves warm drinks, warm clothing, and voluntary physical activity.[2] In those with moderate hypothermia, heating blankets and warmed intravenous fluids are recommended.[2] People with moderate or severe hypothermia should be moved gently.[2] In severe hypothermia, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or cardiopulmonary bypass may be useful.[2] In those without a pulse, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is indicated along with the above measures.[2] Rewarming is typically continued until a person's temperature is greater than 32 °C (90 °F).[2] If there is no improvement at this point or the blood potassium level is greater than 12 mmol/liter at any time, resuscitation may be discontinued.[2]

Hypothermia is the cause of at least 1,500 deaths a year in the United States.[2] It is more common in older people and males.[5] One of the lowest documented body temperatures from which someone with accidental hypothermia has survived is 13.0 °C (55.4 °F) in a near-drowning of a 7-year-old girl in Sweden.[6] Survival after more than six hours of CPR has been described.[2] In individuals for whom ECMO or bypass is used, survival is around 50%.[2] Deaths due to hypothermia have played an important role in many wars.[1]

The term is from Greek ῠ̔πο (ypo), meaning "under", and θέρμη (thérmē), meaning "heat". The opposite of hypothermia is hyperthermia, an increased body temperature due to failed thermoregulation.[7][8]

Classification

| Swiss system[2] | Symptoms | By degree[9] | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Awake and shivering | Mild | 32–35 °C (89.6–95.0 °F) |

| Stage 2 | Drowsy and not shivering | Moderate | 28–32 °C (82.4–89.6 °F) |

| Stage 3 | Unconscious, not shivering | Severe | 20–28 °C (68.0–82.4 °F) |

| Stage 4 | No vital signs | Profound | <20 °C (68.0 °F) |

Hypothermia is often defined as any body temperature below 35.0 °C (95.0 °F). With this method it is divided into degrees of severity based on the core temperature.[9]

Another classification system, the Swiss staging system, divides hypothermia based on the presenting symptoms which is preferred when it is not possible to determine an accurate core temperature.[2]

Other cold-related injuries that can be present either alone or in combination with hypothermia include:

- Chilblains: condition caused by repeated exposure of skin to temperatures just above freezing. The cold causes damage to small blood vessels in the skin. This damage is permanent and the redness and itching will return with additional exposure. The redness and itching typically occurs on cheeks, ears, fingers, and toes.[10]

- Frostbite: the freezing and destruction of tissue,[11] which happens below the freezing point of water

- Frostnip: a superficial cooling of tissues without cellular destruction[12]

- Trench foot or immersion foot: a condition caused by repetitive exposure to water at non-freezing temperatures[11]

The normal human body temperature is often stated as 36.5–37.5 °C (97.7–99.5 °F).[13] Hyperthermia and fever, are defined as a temperature of greater than 37.5–38.3 °C (99.5–100.9 °F).[8]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms vary depending on the degree of hypothermia, and may be divided by the three stages of severity. People with hypothermia may appear pale and feel cold to touch. Infants with hypothermia may feel cold when touched, with bright red skin and an unusual lack of energy.[14]

Cold stress refers to a near-normal body temperature with low skin temperature, signs include shivering. Cold stress is caused by cold exposure and it can lead to hypothermia and frostbite if not treated.

Individuals with hypothermia often have impaired judgement, impaired sense of time and place, unusual aggression and numbness. A person with hypothermia can be euphoric and hallucinating.

Mild

Symptoms of mild hypothermia may be vague,[15] with sympathetic nervous system excitation (shivering, high blood pressure, fast heart rate, fast respiratory rate, and contraction of blood vessels). These are all physiological responses to preserve heat.[16] Increased urine production due to cold, mental confusion, and liver dysfunction may also be present.[17] Hyperglycemia may be present, as glucose consumption by cells and insulin secretion both decrease, and tissue sensitivity to insulin may be blunted.[18] Sympathetic activation also releases glucose from the liver. In many cases, however, especially in people with alcoholic intoxication, hypoglycemia appears to be a more common cause.[18] Hypoglycemia is also found in many people with hypothermia, as hypothermia may be a result of hypoglycemia.[19]

Moderate

As hypothermia progresses, symptoms include: mental status changes such as amnesia, confusion, slurred speech, decreased reflexes, and loss of fine motor skills.[20]

Severe

As the temperature decreases, further physiological systems falter and heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure all decrease. This results in an expected heart rate in the 30s at a temperature of 28 °C (82 °F).[17]

There is often cold, inflamed skin, hallucinations, lack of reflexes, fixed dilated pupils, low blood pressure, pulmonary edema, and shivering is often absent.[20] Pulse and respiration rates decrease significantly, but fast heart rates (ventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation) can also occur. Atrial fibrillation is not typically a concern in and of itself.[2]

Paradoxical undressing

Twenty to fifty percent of hypothermia deaths are associated with paradoxical undressing. This typically occurs during moderate and severe hypothermia, as the person becomes disoriented, confused, and combative. They may begin discarding their clothing, which, in turn, increases the rate of heat loss.[21][22]

Rescuers who are trained in mountain survival techniques are taught to expect this; however, people who die from hypothermia in urban environments who are found in an undressed state are sometimes incorrectly assumed to have been subjected to sexual assault.[23]

One explanation for the effect is a cold-induced malfunction of the hypothalamus, the part of the brain that regulates body temperature. Another explanation is that the muscles contracting peripheral blood vessels become exhausted (known as a loss of vasomotor tone) and relax, leading to a sudden surge of blood (and heat) to the extremities, causing the person to feel overheated.[23][24]

Terminal burrowing

An apparent self-protective behaviour, known as "terminal burrowing", or "hide-and-die syndrome",[25] occurs in the final stages of hypothermia. Those affected will enter small, enclosed spaces, such as underneath beds or behind wardrobes. It is often associated with paradoxical undressing.[26] Researchers in Germany claim this is "obviously an autonomous process of the brain stem, which is triggered in the final state of hypothermia and produces a primitive and burrowing-like behavior of protection, as seen in hibernating mammals".[27] This happens mostly in cases where temperature drops slowly.[24]

Causes

Hypothermia usually occurs from exposure to low temperatures, and is frequently complicated by alcohol consumption. Any condition that decreases heat production, increases heat loss, or impairs thermoregulation, however, may contribute.[1] Thus, hypothermia risk factors include: substance use disorders (including alcohol use disorder), homelessness, any condition that affects judgment (such as hypoglycemia), the extremes of age, poor clothing, chronic medical conditions (such as hypothyroidism and sepsis), and living in a cold environment.[28][29] Hypothermia occurs frequently in major trauma, and is also observed in severe cases of anorexia nervosa. Hypothermia is also associated with worse outcomes in people with sepsis.[30] While most people with sepsis develop fevers (elevated body temperature), some develop hypothermia.[30]

In urban areas, hypothermia frequently occurs with chronic cold exposure, such as in cases of homelessness, as well as with immersion accidents involving drugs, alcohol or mental illness.[31] While studies have shown that people experiencing homelessness are at risk of premature death from hypothermia, the true incidence of hypothermia-related deaths in this population is difficult to determine.[32] In more rural environments, the incidence of hypothermia is higher among people with significant comorbidities and less able to move independently.[31] With rising interest in wilderness exploration, and outdoor and water sports, the incidence of hypothermia secondary to accidental exposure may become more frequent in the general population.[31]

Alcohol

Alcohol consumption increases the risk of hypothermia in two ways: vasodilation and temperature controlling systems in the brain.[30][33][34] Vasodilation increases blood flow to the skin, resulting in heat being lost to the environment.[33] This produces the effect of feeling warm, when one is actually losing heat.[34] Alcohol also affects the temperature-regulating system in the brain, decreasing the body's ability to shiver and use energy that would normally aid the body in generating heat.[33] The overall effects of alcohol lead to a decrease in body temperature and a decreased ability to generate body heat in response to cold environments.[34] Alcohol is a common risk factor for death due to hypothermia.[33] Between 33% and 73% of hypothermia cases are complicated by alcohol.[30]

Water immersion

Hypothermia continues to be a major limitation to swimming or diving in cold water.[35] The reduction in finger dexterity due to pain or numbness decreases general safety and work capacity, which consequently increases the risk of other injuries.[35][36]

Other factors predisposing to immersion hypothermia include dehydration, inadequate rewarming between repetitive dives, starting a dive while wearing cold, wet dry suit undergarments, sweating with work, inadequate thermal insulation (for example, thin dry suit undergarment), and poor physical conditioning.[35]

Heat is lost much more quickly in water[35] than in air. Thus, water temperatures that would be quite reasonable as outdoor air temperatures can lead to hypothermia in survivors, although this is not usually the direct clinical cause of death for those who are not rescued. A water temperature of 10 °C (50 °F) can lead to death in as little as one hour, and water temperatures near freezing can cause death in as little as 15 minutes.[37] During the sinking of the Titanic, most people who entered the −2 °C (28 °F) water died in 15–30 minutes.[38]

The actual cause of death in cold water is usually the bodily reactions to heat loss and to freezing water, rather than hypothermia (loss of core temperature) itself. For example, plunged into freezing seas, around 20% of victims die within two minutes from cold shock (uncontrolled rapid breathing, and gasping, causing water inhalation, massive increase in blood pressure and cardiac strain leading to cardiac arrest, and panic); another 50% die within 15–30 minutes from cold incapacitation: inability to use or control limbs and hands for swimming or gripping, as the body "protectively" shuts down the peripheral muscles of the limbs to protect its core.[39] Exhaustion and unconsciousness cause drowning, claiming the rest within a similar time.[37]

Pathophysiology

| Temperature classification | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Note: The difference between fever and hyperthermia is the underlying mechanism. Different sources have different cut-offs for fever, hyperthermia and hyperpyrexia. | ||||||||||||

Heat is primarily generated in muscle tissue, including the heart, and in the liver, while it is lost through the skin (90%) and lungs (10%). Heat production may be increased two- to four-fold through muscle contractions (i.e. exercise and shivering). The rate of heat loss is determined, as with any object, by convection, conduction, and radiation.[15] The rates of these can be affected by body mass index, body surface area to volume ratios, clothing and other environmental conditions.[45]

Many changes to physiology occur as body temperatures decrease. These occur in the cardiovascular system leading to the Osborn J wave and other dysrhythmias, decreased central nervous system electrical activity, cold diuresis, and non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema.[46]

Research has shown that glomerular filtration rates (GFR) decrease as a result of hypothermia.[47] In essence, hypothermia increases preglomerular vasoconstriction, thus decreasing both renal blood flow (RBF) and GFR.[48]

Diagnosis

Accurate determination of core temperature often requires a special low temperature thermometer, as most clinical thermometers do not measure accurately below 34.4 °C (93.9 °F).[16] A low temperature thermometer can be placed in the rectum, esophagus or bladder. Esophageal measurements are the most accurate and are recommended once a person is intubated.[2] Other methods of measurement such as in the mouth, under the arm, or using an infrared ear thermometer are often not accurate.[2]

As a hypothermic person's heart rate may be very slow, prolonged feeling for a pulse could be required before detecting. In 2005, the American Heart Association recommended at least 30–45 seconds to verify the absence of a pulse before initiating CPR.[49] Others recommend a 60-second check.[2]

The classical ECG finding of hypothermia is the Osborn J wave. Also, ventricular fibrillation frequently occurs below 28 °C (82 °F) and asystole below 20 °C (68 °F).[15] The Osborn J may look very similar to those of an acute ST elevation myocardial infarction.[17] Thrombolysis as a reaction to the presence of Osborn J waves is not indicated, as it would only worsen the underlying coagulopathy caused by hypothermia.

Prevention

Proper clothing helps to prevent hypothermia. Synthetic and wool fabrics are superior to cotton as they provide better insulation when wet and dry. Some synthetic fabrics, such as polypropylene and polyester, are used in clothing designed to wick perspiration away from the body, such as liner socks and moisture-wicking undergarments. Clothing should be loose fitting, as tight clothing reduces the circulation of warm blood.[50] In planning outdoor activity, prepare appropriately for possible cold weather. Those who drink alcohol before or during outdoor activity should ensure at least one sober person is present responsible for safety.

Covering the head is effective, but no more effective than covering any other part of the body. While common folklore says that people lose most of their heat through their heads, heat loss from the head is no more significant than that from other uncovered parts of the body.[51][52] However, heat loss from the head is significant in infants, whose head is larger relative to the rest of the body than in adults. Several studies have shown that for uncovered infants, lined hats significantly reduce heat loss and thermal stress.[53][54][55] Children have a larger surface area per unit mass, and other things being equal should have one more layer of clothing than adults in similar conditions, and the time they spend in cold environments should be limited. However children are often more active than adults, and may generate more heat. In both adults and children, overexertion causes sweating and thus increases heat loss.[56]

Building a shelter can aid survival where there is danger of death from exposure. Shelters can be of many different types, metal can conduct heat away from the occupants and is sometimes best avoided. The shelter should not be too big so body warmth stays near the occupants. Good ventilation is essential especially if a fire will be lit in the shelter. Fires should be put out before the occupants sleep to prevent carbon monoxide poisoning. People caught in very cold, snowy conditions can build an igloo or snow cave to shelter.[57][58]

The United States Coast Guard promotes using life vests to protect against hypothermia through the 50/50/50 rule: If someone is in 50 °F (10 °C) water for 50 minutes, he/she has a 50 percent better chance of survival if wearing a life jacket.[59] A heat escape lessening position can be used to increase survival in cold water.

Babies should sleep at 16–20 °C (61–68 °F) and housebound people should be checked regularly to make sure the temperature of the home is at least 18 °C (64 °F).[27][56][60] [61]

Management

| Degree[2][49] | Rewarming technique |

|---|---|

| Mild (stage 1) | Passive rewarming |

| Moderate (stage 2) | Active external rewarming |

| Severe (stage 3 and 4) | Active internal rewarming |

Aggressiveness of treatment is matched to the degree of hypothermia.[2] Treatment ranges from noninvasive, passive external warming to active external rewarming, to active core rewarming.[16] In severe cases resuscitation begins with simultaneous removal from the cold environment and management of the airway, breathing, and circulation. Rapid rewarming is then commenced. Moving the person as little and as gently as possible is recommended as aggressive handling may increase risks of a dysrhythmia.[49]

Hypoglycemia is a frequent complication and needs to be tested for and treated. Intravenous thiamine and glucose is often recommended, as many causes of hypothermia are complicated by Wernicke's encephalopathy.[62]

The UK National Health Service advises against putting a person in a hot bath, massaging their arms and legs, using a heating pad, or giving them alcohol. These measures can cause a rapid fall in blood pressure and potential cardiac arrest.[63]

Rewarming

Rewarming can be done with a number of methods including passive external rewarming, active external rewarming, and active internal rewarming.[64] Passive external rewarming involves the use of a person's own ability to generate heat by providing properly insulated dry clothing and moving to a warm environment.[65] Passive external rewarming is recommended for those with mild hypothermia.[65]

Active external rewarming involves applying warming devices externally, such as a heating blanket.[2] These may function by warmed forced air (Bair Hugger is a commonly used device), chemical reactions, or electricity.[2][65] In wilderness environments, hypothermia may be helped by placing hot water bottles in both armpits and in the groin.[66] Active external rewarming is recommended for moderate hypothermia.[65] Active core rewarming involves the use of intravenous warmed fluids, irrigation of body cavities with warmed fluids (the chest or abdomen), use of warm humidified inhaled air, or use of extracorporeal rewarming such as via a heart lung machine or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).[64] Extracorporeal rewarming is the fastest method for those with severe hypothermia.[65] When severe hypothermia has led to cardiac arrest, effective extracorporeal warming results in survival with normal mental function about 50% of the time. Chest irrigation is recommended if bypass or ECMO is not possible.[2]

Rewarming shock (or rewarming collapse) is a sudden drop in blood pressure in combination with a low cardiac output which may occur during active treatment of a severely hypothermic person.[67][68] There was a theoretical concern that external rewarming rather than internal rewarming may increase the risk.[2] These concerns were partly believed to be due to afterdrop, a situation detected during laboratory experiments where there is a continued decrease in core temperature after rewarming has been started.[2] Recent studies have not supported these concerns, and problems are not found with active external rewarming.[2][49]

Fluids

For people who are alert and able to swallow, drinking warm sweetened liquids can help raise the temperature.[2] Many recommend alcohol and caffeinated drinks be avoided.[69] As most people are moderately dehydrated due to cold-induced diuresis, warmed intravenous fluids to a temperature of 38–45 °C (100–113 °F) are often recommended.[2][16]

Cardiac arrest

In those without signs of life, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be continued during active rewarming.[2] For ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia, a single defibrillation should be attempted.[70] However, people with severe hypothermia may not respond to pacing or defibrillation.[70] It is not known if further defibrillation should be withheld until the core temperature reaches 30 °C (86 °F).[70] In Europe, epinephrine is not recommended until the person's core temperature reaches 30 °C (86 °F), while the American Heart Association recommends up to three doses of epinephrine before a core temperature of 30 °C (86 °F) is reached.[2] Once a temperature of 30 °C (86 °F) has been reached, normal ACLS protocols should be followed.[49]

Prognosis

It is usually recommended not to declare a person dead until their body is warmed to a near normal body temperature of greater than 32 °C (90 °F),[2] since extreme hypothermia can suppress heart and brain function.[71] This is summarized in the common medical school advice "You're not dead until you're warm and dead."[72] Exceptions include if there are obvious fatal injuries or the chest is frozen so that it cannot be compressed.[49] If a person was buried in an avalanche for more than 35 minutes and is found with a mouth packed full of snow without a pulse, stopping early may also be reasonable.[2] This is also the case if a person's blood potassium is greater than 12 mmol/L.[2]

Those who are stiff with pupils that do not move may survive if treated aggressively.[2] Survival with good function also occasionally occurs even after the need for hours of CPR.[2] Children who have near-drowning accidents in water near 0 °C (32 °F) can occasionally be revived, even over an hour after losing consciousness.[73][74] The cold water lowers the metabolism, allowing the brain to withstand a much longer period of hypoxia. While survival is possible, mortality from severe or profound hypothermia remains high despite optimal treatment. Studies estimate mortality at between 38%[75][76] and 75%.[15]

In those who have hypothermia due to another underlying health problem, when death occurs it is frequently from that underlying health problem.[2]

Epidemiology

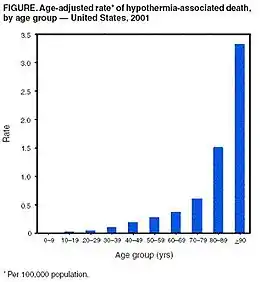

Between 1995 and 2004 in the United States, an average of 1560 cold-related emergency department visits occurred per year and in the years 1999 to 2004, an average of 647 people died per year due to hypothermia.[28][77] Of deaths reported between 1999 and 2002 in the US, 49% of those affected were 65 years or older and two-thirds were male.[32] Most deaths were not work related (63%) and 23% of affected people were at home.[32] Hypothermia was most common during the autumn and winter months of October through March.[32] In the United Kingdom, an estimated 300 deaths per year are due to hypothermia, whereas the annual incidence of hypothermia-related deaths in Canada is 8000.[32]

History

Hypothermia has played a major role in the success or failure of many military campaigns, from Hannibal's loss of nearly half his men in the Second Punic War (218 B.C.) to the near destruction of Napoleon's armies in Russia in 1812. Men wandered around confused by hypothermia, some lost consciousness and died, others shivered, later developed torpor, and tended to sleep. Others too weak to walk fell on their knees; some stayed that way for some time resisting death. The pulse of some was weak and hard to detect; others groaned; yet others had eyes open and wild with quiet delirium.[78] Deaths from hypothermia in Russian regions continued through the first and second world wars, especially in the Battle of Stalingrad.[79]

Civilian examples of deaths caused by hypothermia occurred during the sinkings of the RMS Titanic and RMS Lusitania, and more recently of the MS Estonia.[80][81][82]

Antarctic explorers developed hypothermia; Ernest Shackleton and his team measured body temperatures "below 94.2°, which spells death at home", though this probably referred to oral temperatures rather than core temperature and corresponded to mild hypothermia. One of Scott's team, Atkinson, became confused through hypothermia.[78]

Nazi human experimentation during World War II amounting to medical torture included hypothermia experiments, which killed many victims. There were 360 to 400 experiments and 280 to 300 subjects, indicating some had more than one experiment performed on them. Various methods of rewarming were attempted: "One assistant later testified that some victims were thrown into boiling water for rewarming".[83]

Medical use

Various degrees of hypothermia may be deliberately induced in medicine for purposes of treatment of brain injury, or lowering metabolism so that total brain ischemia can be tolerated for a short time. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest is a medical technique in which the brain is cooled as low as 10 °C, which allows the heart to be stopped and blood pressure to be lowered to zero, for the treatment of aneurysms and other circulatory problems that do not tolerate arterial pressure or blood flow. The time limit for this technique, as also for accidental arrest in ice water (which internal temperatures may drop to as low as 15 °C), is about one hour.[84]

Other animals

Hypothermia can happen in most mammals in cold weather and can be fatal. Baby mammals, kittens for example, are unable to regulate their body temperatures and have great risk of hypothermia if they are not kept warm by their mothers.

Many animals other than humans often induce hypothermia during hibernation or torpor.

Water bears (Tardigrade), microscopic multicellular organisms, can survive freezing at low temperatures by replacing most of their internal water with the sugar trehalose, preventing the crystallization that otherwise damages cell membranes.

See also

- Diving reflex – The physiological responses to immersion of air-breathing vertebrates

- "To Build a Fire" – Short story by Jack London, two versions of a short story by Jack London portraying the effects of cold and hypothermia

- "The Little Match Girl" – Fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, a short story by Hans Christian Andersen about a child dying of hypothermia

- Dyatlov Pass incident

References

- Marx J (2010). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice 7th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 1870. ISBN 978-0-323-05472-0.

- Brown DJ, Brugger H, Boyd J, Paal P (November 2012). "Accidental hypothermia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (20): 1930–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1114208. PMID 23150960. S2CID 205116341.

- Fears, J. Wayne (February 14, 2011). The Pocket Outdoor Survival Guide: The Ultimate Guide for Short-Term Survival. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-62636-680-0.

- Robertson, David (2012). Primer on the autonomic nervous system (3rd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier/AP. p. 288. ISBN 9780123865250. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017.

- Bracker, Mark (2012). The 5-Minute Sports Medicine Consult (2 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 320. ISBN 9781451148121. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017.

- "Remarkable recovery of seven-year-old girl". Sveriges Radio. January 17, 2011. Archived from the original on March 7, 2015. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- Axelrod YK, Diringer MN (May 2008). "Temperature management in acute neurologic disorders". Neurologic Clinics. 26 (2): 585–603, xi. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2008.02.005. PMID 18514828.

- Laupland KB (July 2009). "Fever in the critically ill medical patient". Critical Care Medicine. 37 (7 Suppl): S273-8. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181aa6117. PMID 19535958.

- Marx J (2006). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. Mosby/Elsevier. p. 2239. ISBN 978-0-323-02845-5.

- "CDC - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic - Cold Stress - Cold Related Illnesses". www.cdc.gov. June 6, 2018. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- "Cold Stress". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012.

- Marx 2010 p.1862

- Karakitsos D, Karabinis A (September 2008). "Hypothermia therapy after traumatic brain injury in children". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (11): 1179–80. doi:10.1056/NEJMc081418. PMID 18788094.

- "Hypothermia". WebMD. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014.

- Hanania NA, Zimmerman JL (1999). "Accidental hypothermia". Critical Care Clinics. 15 (2): 235–49. doi:10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70052-x. PMID 10331126.

- McCullough L, Arora S (December 2004). "Diagnosis and treatment of hypothermia". American Family Physician. 70 (12): 2325–32. PMID 15617296.

- Marx 2010 p.1869

- Altus P, Hickman JW (May 1981). "Accidental hypothermia: hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia". Western Journal of Medicine. 134 (5): 455–6. PMC 1272797. PMID 7257359.

- eMedicine Specialties > Emergency Medicine > Environmental >Hypothermia Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine Author: Jamie Alison Edelstein, MD. Coauthors: James Li, MD; Mark A Silverberg, MD; Wyatt Decker, MD. Updated: October 29, 2009

- Petrone P, Asensio JA, Marini CP (October 2014). "Management of accidental hypothermia and cold injury". Current Problems in Surgery. 51 (10): 417–31. doi:10.1067/j.cpsurg.2014.07.004. PMID 25242454.

- New Scientist (2007). "The word: Paradoxical undressing – being-human". New Scientist. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- Turk, EE (June 2010). "Hypothermia". Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology. 6 (2): 106–15. doi:10.1007/s12024-010-9142-4. PMID 20151230.

- Ramsay, David; Michael J. Shkrum (2006). Forensic Pathology of Trauma (Forensic Science and Medicine). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. p. 417. ISBN 1-58829-458-7.

- Rothschild MA, Schneider V (1995). "'Terminal burrowing behaviour'—a phenomenon of lethal hypothermia". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 107 (5): 250–6. doi:10.1007/BF01245483. PMID 7632602. S2CID 29253926.

- Carter N, Green MA, Milroy CM, Clark JC (1995). "Letter to the editor: Terminal burrowing behaviour — a phenomenon of lethal hypothermia". International Journal of Legal Medicine. Berlin / Heidelberg: Springer. 108 (2): 116. doi:10.1007/BF01369918. PMID 8547158. S2CID 11047611.

- Rothschild MA, Schneider V (1995). ""Terminal burrowing behaviour"--a phenomenon of lethal hypothermia". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 107 (5): 250–6. doi:10.1007/BF01245483. PMID 7632602. S2CID 29253926.

- December 2013, Marc Lallanilla-Live Science Contributor 05. "Get Naked and Dig: The Bizarre Effects of Hypothermia". livescience.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Baumgartner, Hypothermia and Other Cold-Related Morbidity Emergency Department Visits: United States, 1995–2004 Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, 19, 233 237 (2008)

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (March 2006). "Hypothermia-related deaths—United States, 1999–2002 and 2005". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 55 (10): 282–4. PMID 16543884.

- Walls, Ron; Hockberger, Robert; Gausche-Hill, Marianne (March 9, 2017). Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice. Walls, Ron M.,, Hockberger, Robert S.,, Gausche-Hill, Marianne (Ninth ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 9780323390163. OCLC 989157341.

- James Li (October 21, 2021). Joe Alcock (ed.). "Hypothermia: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". Medscape.

- "BMJ Best Practice". bestpractice.bmj.com. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- Mihic J, Koob G, Mayfield J, Harris A, Brunton L, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollmann B (2017). "Ethanol". 's: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (13 ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-1259584732.

- Danzl D, Jameson L, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S (2018). "Hypothermia and Peripheral Cold Injuries". Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (20th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-1259644030.

- Sterba, JA (1990). Field Management of Accidental Hypothermia during Diving. US Navy Experimental Diving Unit Technical Report (Report). Navy Experimental Diving Unit Panama City Fla. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Cheung SS, Montie DL, White MD, Behm D (September 2003). "Changes in manual dexterity following short-term hand and forearm immersion in 10 degrees C water". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 74 (9): 990–3. PMID 14503680. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- "Hypothermia safety". United States Power Squadrons. January 23, 2007. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- Sinking of the RMS Titanic#CITEREFButler1998

- Vittone M (October 21, 2010). "The Truth About Cold Water". Survival. Mario Vittone. Archived from the original on January 14, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- Marx J (2006). Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 2239. ISBN 978-0-323-02845-5. OCLC 58533794.

- Hutchison JS, Ward RE, Lacroix J, Hébert PC, Barnes MA, Bohn DJ, et al. (June 2008). "Hypothermia therapy after traumatic brain injury in children". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (23): 2447–56. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706930. PMID 18525042.

- Pryor JA, Prasad AS (2008). Physiotherapy for Respiratory and Cardiac Problems: Adults and Paediatrics. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 8. ISBN 978-0702039744.

Body temperature is maintained within the range 36.5-37.5 °C. It is lowest in the early morning and highest in the afternoon.

- Grunau BE, Wiens MO, Brubacher JR (September 2010). "Dantrolene in the treatment of MDMA-related hyperpyrexia: a systematic review". Cjem. 12 (5): 435–42. doi:10.1017/s1481803500012598. PMID 20880437.

Dantrolene may also be associated with improved survival and reduced complications, especially in patients with extreme (≥ 42 °C) or severe (≥ 40 °C) hyperpyrexia

- Sharma HS, ed. (2007). Neurobiology of Hyperthermia (1st ed.). Elsevier. pp. 175–177, 485. ISBN 9780080549996. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

Despite the myriad of complications associated with heat illness, an elevation of core temperature above 41.0 °C (often referred to as fever or hyperpyrexia) is the most widely recognized symptom of this syndrome.

- Nuckton TJ, Claman DM, Goldreich D, Wendt FC, Nuckton JG (October 2000). "Hypothermia and afterdrop following open water swimming: the Alcatraz/San Francisco Swim Study". American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 18 (6): 703–7. doi:10.1053/ajem.2000.16313. PMID 11043627.

- Marx J (2010). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice 7th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. pp. 1869–1870. ISBN 978-0-323-05472-0.

- Broman M, Källskog O (1995). "The effects of hypothermia on renal function and haemodynamics in the rat". Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 153 (2): 179–184. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1995.tb09849.x. PMID 7778458.

- Broman M, Källskog O, Kopp UC, Wolgast M (1998). "Influence of the sympathetic nervous system on renal function during hypothermia". Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 163 (3): 241–249. doi:10.1046/j.1365-201x.1998.00356.x. PMID 9715736.

- ECC Committee, Subcommittees and Task Forces of the American Heart Association (December 2005). "2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 112 (24 Suppl): IV–136. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166550. PMID 16314375. Archived from the original on March 24, 2011.

- "Workplace Safety & Health Topics: Cold Stress". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- Sessler DI, Moayeri A, Støen R, Glosten B, Hynson J, McGuire J (1990). "Thermoregulatory vasoconstriction decreases cutaneous heat loss". Anesthesiology. 73 (4): 656–60. doi:10.1097/00000542-199010000-00011. PMID 2221434.

- Sample, Ian (December 18, 2008). "Scientists debunk myth that most heat is lost through head | Science". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on September 5, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- Stothers JK (1981). "Head insulation and heat loss in the newborn". Archives of Disease in Childhood. Royal Coll Paediatrics. 56 (7): 530–534. doi:10.1136/adc.56.7.530. PMC 1627361. PMID 7271287.

- Chaput de Saintonge DM, Cross KW, Shathorn MK, Lewis SR, Stothers JK (September 2, 1979). "Hats for the newborn infant". British Medical Journal. 2 (6190): 570–1. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.6190.570. PMC 1596505. PMID 387172.

- Lang N, Bromiker R, Arad I (November 2004). "The effect of wool vs. cotton head covering and length of stay with the mother following delivery on infant temperature". International Journal of Nursing Studies. 41 (8): 843–846. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.03.010. PMID 15476757.

- "Hypothermia - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014.

- How to build an Igloo, survive a blizzard, finish your mission on time Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine This web page gives basic instructions for westerners.

- Cold Weather Survival, Shelkters Archived 2014-01-18 at the Wayback Machine This has instructions about building different types of shelter

- United States Coast Guard. "Rescue and Survival Systems Manual" (PDF). United States Coast Guard. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- "Hypothermia". nhs.uk. October 18, 2017. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014.

- "Hypothermia (cont.)". Archived from the original on January 12, 2014.

- Tintinalli J (2004). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 1181. ISBN 0-07-138875-3.

- "Hypothermia". nhs.uk. October 18, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- McCullough L, Arora S (December 2004). "Diagnosis and treatment of hypothermia". American Family Physician. 70 (12): 2325–32. PMID 15617296.

- Vanden Hoek TL, Morrison LJ, Shuster M, Donnino M, Sinz E, Lavonas EJ, Jeejeebhoy FM, Gabrielli A (November 2, 2010). "Part 12: cardiac arrest in special situations: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S829–61. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971069. PMID 20956228.

- Auerbach PS, ed. (2007). Wilderness medicine (5th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier Mosby. pp. Chapter 5. ISBN 978-0-323-03228-5.

- Tveita T (October 2000). "Rewarming from hypothermia. Newer aspects on the pathophysiology of rewarming shock". International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 59 (3–4): 260–6. PMID 11209678.

- Kondratiev TV, Myhre ES, Simonsen O, Nymark TB, Tveita T (February 2006). "Cardiovascular effects of epinephrine during rewarming from hypothermia in an intact animal model". Journal of Applied Physiology. 100 (2): 457–64. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00356.2005. PMID 16210439. S2CID 748884.

- Auerbach PS, ed. (2011). "Accidental Hypothermia". Wilderness medicine (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. pp. Chapter 5. ISBN 978-1437716788.

- Vanden Hoek TL, Morrison LJ, Shuster M, Donnino M, Sinz E, Lavonas EJ, Jeejeebhoy FM, Gabrielli A (2010). "Part 12: cardiac arrest in special situations: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S829–61. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971069. PMID 20956228.

- Iyer A, Rajkumar V, Sadasivan D, Bruce J, Gilfillan I (2007). "No one is dead until warm and dead". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 134 (4): 1042–3. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.05.028. PMID 17903527.

- Foggle, John L. (February 2019). "Accidental Hypothermia: 'You're Not Dead Until You're Warm and Dead'". Rhode Island Medical Journal. 102 (1): 28–32. PMID 30709071.

- Bolte RG, Black PG, Bowers RS, Thorne JK, Corneli HM (1988). "The use of extracorporeal rewarming in a child submerged for 66 minutes". Journal of the American Medical Association. 260 (3): 377–379. doi:10.1001/jama.260.3.377. PMID 3379747.

- Life after Death: How seven kids came back from the dead https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/stories-50630441/life-after-death-how-seven-kids-came-back-from-the-dead

- Morita S, Seiji M, Inokuchi S, Sadaki I, Inoue S, Shigeaki I, Akieda K, Kazuki A, Umezawa K, Kazuo U, Nakagawa Y, Yoshihide N, Yamamoto I, Isotoshi Y (December 2008). "The efficacy of rewarming with a portable and percutaneous cardiopulmonary bypass system in accidental deep hypothermia patients with hemodynamic instability". The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 65 (6): 1391–5. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181485490. PMID 19077632.

- Vassal T, Benoit-Gonin B, Carrat F, Guidet B, Maury E, Offenstadt G (December 2001). "Severe accidental hypothermia treated in an ICU: prognosis and outcome". Chest. 120 (6): 1998–2003. doi:10.1378/chest.120.6.1998. PMID 11742934. S2CID 10672639.

- "Hypothermia-Related Mortality – Montana, 1999–2004". Archived from the original on April 24, 2009.

- Guly, H (January 2011). "History of accidental hypothermia". Resuscitation. 82 (1): 122–5. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.09.465. PMC 3060344. PMID 21036455.

- Marx J (2010). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice 7th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 1868. ISBN 978-0-323-05472-0.

- "Findings: Titanic victims in 'cold shock'". May 24, 2002. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- John Updike (July 1, 2002). "Remember the Lusitania". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- Soomer H, Ranta H, Penttilä A (2001). "Identification of victims from the M/S Estonia". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 114 (4–5): 259–262. doi:10.1007/s004140000180. PMID 11355406. S2CID 38587050.

- Berger, RL (May 17, 1990). "Nazi science--the Dachau hypothermia experiments". The New England Journal of Medicine. 322 (20): 1435–40. doi:10.1056/NEJM199005173222006. PMID 2184357.

- Conolly S, Arrowsmith JE, Klein AA (July 2010). "Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest". Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain. 10 (5): 138–142. doi:10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkq024.

Most patients tolerate 30 min of DHCA without significant neurological dysfunction, but when this is extended to longer than 40 min, there is a marked increase in the incidence of brain injury. Above 60 min, the majority of patients will suffer irreversible brain injury, although there are still a small number of patients who can tolerate this.

- Bibliography

- Marx J (2010). Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 1862. ISBN 978-0-323-05472-0.

External links

- CDC - NIOSH Workplace Safety & Health Topic: Cold Stress