Cruciate ligament

Cruciate ligaments (also cruciform ligaments) are pairs of ligaments arranged like a letter X.[1] They occur in several joints of the body, such as the knee joint and the atlanto-axial joint. In a fashion similar to the cords in a toy Jacob's ladder, the crossed ligaments stabilize the joint while allowing a very large range of motion.

| Cruciate ligaments | |

|---|---|

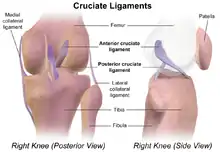

Illustration of the ligaments of the knee, including the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments | |

| Anatomical terminology |

Knee

Structure

Cruciate ligaments occur in the knee of humans and other bipedal animals and the corresponding stifle of quadrupedal animals, and in the neck, fingers, and foot.

- The cruciate ligaments of the knee are the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). These ligaments are two strong, rounded bands that extend from the head of the tibia to the intercondyloid notch of the femur. The ACL is lateral and the PCL is medial. They cross each other like the limbs of an X. They are named for their insertion into the tibia: the ACL attaches to the anterior aspect of the intercondylar area, the PCL to the posterior aspect. The ACL and PCL remain distinct throughout and each has its own partial synovial sheath. Relative to the femur, the ACL keeps the tibia from slipping forward and the PCL keeps the tibia from slipping backward.

- Another structure of this type in human anatomy is the cruciate ligament of the dens of the atlas vertebra, also called "cruciform ligament of the atlas", a ligament in the neck forming part of the atlanto-axial joint.[2]

- In the fingers, the deep and superficial flexor tendons pass through a fibro-osseous tunnel system – the flexor mechanism – of annular and cruciate ligaments called pulleys. The cruciate pulleys tether the long flexor tendons. The number and extent of these cruciate and annular ligaments varies among individuals, but three cruciate and four or five annular ligaments are normally found in each finger (usually referred to as, for example, "A1 pulley" and "C1 pulley"). The thumb has a similar system for its long flexor tendon but with a single oblique pulley replacing the cruciate pulleys found in the fingers.[3]

- The human foot has a cruciate crural ligament, also known as inferior extensor retinaculum of foot. The equine foot has a pair of cruciate distal sesamoidean ligaments in the metacarpophalangeal joint. These ligaments can be seen using computed tomography.[4]

Rupture

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament is one of the "most frequent acquired diseases of the stifle joint"[5] in humans, dogs, and cats; direct trauma to the joint is relatively uncommon and age appears to be a major factor.[5]

Cruciate ligament injuries are common in animals, and in 2005 a study estimated that $1.32 billion was spent in the United States in treating the cranial cruciate ligament of dogs.[6]

Rupture in canines and surgical repair techniques

- In animals the two cruciate ligaments that cross the inside of the knee joint are referred to as the cranial cruciate (equivalent to anterior in humans) and the caudal cruciate (equivalent to the posterior in humans). The cranial cruciate ligament prevents the tibia from slipping forward out from under the femur.[7]

- Stifle injuries are one of the most common causes of lameness in rear limbs in dogs, and cruciate ligament injuries are the most common lesion in the stifle joint. A rupture of the cruciate ligament usually involves a rear leg to suddenly become so sore that the dog can barely bear weight on it.[7]

- How a rupture can occur:

- There are several ways a dog can tear or rupture the cruciate ligament. Young athletic dogs can be seen with this rupture if they take a bad step while playing too rough and injure their knee. Older dogs, especially if overweight, can have weakened ligaments that can be stretched or torn by simply stepping down off the bed or jumping.[7]

- Large overweight dogs are at more risk for ruptures of the cruciate ligament. In these instances it is common to see a rupture in the other leg within a year's time of the first rupture.[7]

- Common breeds that are seen with cruciate ligament ruptures:

- In recent survey's some of the large breed dogs that seem to be at risk for obtaining these ruptures were: Neapolitan mastiff, Newfoundland, St. Bernard, Rottweiler, Chesapeake Bay retriever, Akita, and American Staffordshire terrier.[7] However, other breeds have been observed with these ruptures, such as: Labradors, Labrador crossbreeds, Poodles, Poodle crossbreeds, Bichon Frises, German Shepherds, Shepherd crossbreeds, and Golden Retrievers.[8]

- Diagnosis:

- History, palpation, observation and proper radiography is important in properly assessing the patient. The key in diagnosing a rupture of the cruciate ligament is the demonstration of an abnormal gait in the dog. Abnormal knee motion is typically observed and diagnosis of a rupture can be made by performing the drawer sign test.[7][9]

- The drawer sign:

- The examiner stands behind the dog and places a thumb on the caudal aspect of the femoral condylar region with the index finger on the patella. The other thumb is placed on the head of the fibula with the index finger on the tibial crest. The ability to move the tibia forward (cranially) with respect to a fixed femur is a positive cranial drawer sign indicative of a rupture (it will look like a drawer being opened).[9]

- Another method used to diagnose a rupture is the tibial compression test, in which a veterinarian will stabilize the femur with one hand and flex the ankle with the other hand. The tibia will move abnormally forward if a rupture is present.[7]

- For proper diagnosis sedation is typically needed since most animals tend to be tense or frightened at the vet's office. If the animal tenses its muscles, temporary stabilization of the knee can be observed which would prevent demonstration of the drawer sign or tibial compression test.[7]

- Radiographs are typically necessary to identify whether bone chips, from where the ligament attaches to the tibia, are present. This can occur when the cruciate ligament tears, and if found will require surgical repair.[7]

- Surgical repair

- Three surgical techniques are commonly used

- Extracapsular repair

- Any bone spurs are removed and a large suture is passed around the fabella behind the knee through a drilled hole in the front of the tibia. This surgical procedure tightens the joint to prevent the drawer motion, and the suture that is put in place takes the job of the cruciate ligament for approximately 2 to 12 months after surgery. The suture will eventually break and the dog will have its own healed tissue that will hold the knee in place.[7][10]

- Tibial plateau leveling osteotomy

- This surgery uses biomechanics of the knee joint and is meant to address the lack of success seen in the extracapsular repair surgery in larger dogs. A stainless steel bone plate is used to hold the two pieces of bone in place. This surgery is complex and typically costs more than the extracapsular repair.[7][11]

- Tibial tuberosity advancement

- This surgery aims at advancing the tibial tuberosity forward in order to modify the pull of the quadriceps muscle group, which in turn helps reduce tibial thrust and ultimately stabilizes the knee. The tibial tuberosity is separated and anchored to its new position by a titanium or steel cage, “fork”, and plate. Bone graft is used to stimulate bone healing.[7][12]

- Extracapsular repair

- Three surgical techniques are commonly used

Other locations

- Cruciate ligament of atlas

- Cruciform ligaments of fingers.

Etymology

In the first edition[13] of the official Latin nomenclature (Nomina Anatomica, renamed in 1998 as Terminologia Anatomica), the Latin expression ligamenta cruciata was used, similar to the expression cruciate ligaments currently in use in English.[14] In classical Latin the verb cruciare is derived from crux, meaning cross.[15] It became considered that cruciate was equivalent to cross-shaped.

References

- Daniel John Cunningham (1918). Cunningham's text-book of anatomy (5th ed.). Oxford Press. p. 1593.

- Anatomy of Spinal Vertebrae Tutorial Archived 2007-10-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- Austin, Noelle M. (2005). "Chapter 9: The Wrist and Hand Complex". In Levangie, Pamela K.; Norkin, Cynthia C. (eds.). Joint Structure and Function: A Comprehensive Analysis (4th ed.). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company. pp. 327–28. ISBN 978-0-8036-1191-7.

- Vanderperren K, Ghaye B, Snaps FR, Saunders JH (May 2008). "Evaluation of computed tomographic anatomy of the equine metacarpophalangeal joint". Am. J. Vet. Res. 69 (5): 631–8. doi:10.2460/ajvr.69.5.631. PMID 18447794.

- Neãas A., J . Zatloukal, H. Kecová, M. Dvofiák: Predisposition of Dog Breeds to Rupture of Cranial Cruciate Ligament Archived 2008-12-09 at the Wayback Machine. Acta Vet. Brno 2000, 69: 305-310..

- Wilke VL. (2005). Estimate of the annual economic impact of treatment of cranial cruciate ligament injury in dogs in the United States. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

- Brooks, Wendy C. Ruptured Anterior (Cranial) Cruciate Ligament. “Veterinary Information Network, Inc.” 2005

- Harasen, Greg Canine cranial cruciate ligament rupture in profile. “The Canadian Veterinary Journal” 2003, 44(10): 845-846

- Harasen, Greg Diagnosing rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament. “The Canadian Veterinary Journal” 2002, 43(6): 475-476

- Tong, Kim Cranial Cruciate Ligament (CCL)- Extracapsular Repair. “Dallas Veterinary Surgical Center” 2015

- Tong, Kim Cranial Cruciate Ligament (CCL)- Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO) “Dallas Veterinary Surgical Center” 2015

- Tong, Kim Cranial Cruciate Ligament (CCL)- Tibial Tuberosity Advancement (TTA) “Dallas Veterinary Surgical Center” 2015

- His, W. (1895). Die anatomische Nomenclatur. Nomina Anatomica. Der von der Anatomischen Gesellschaft auf ihrer IX. Versammlung in Basel angenommenen Namen. Leipzig: Verlag Veit & Comp.

- Anderson, D.M. (2000). Dorland’s illustrated medical dictionary (29th edition). Philadelphia/London/Toronto/Montreal/Sydney/Tokyo: W.B. Saunders Company.

- Lewis, C.T. & Short, C. (1879). A Latin dictionary founded on Andrews' edition of Freund's Latin dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.