Flexor pollicis longus muscle

The flexor pollicis longus (/ˈflɛksər ˈpɒlɪsɪs ˈlɒŋɡəs/; FPL, Latin flexor, bender; pollicis, of the thumb; longus, long) is a muscle in the forearm and hand that flexes the thumb. It lies in the same plane as the flexor digitorum profundus. This muscle is unique to humans, being either rudimentary or absent in other primates.[1] A meta-analysis indicated accessory flexor pollicis longus is present in around 48% of the population.[2]

| Flexor pollicis longus muscle | |

|---|---|

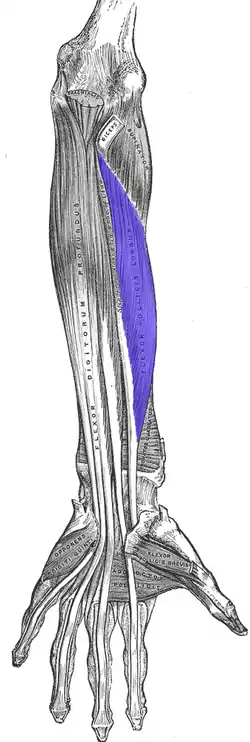

Front of the left forearm. Deep muscles. (Flexor pollicis longus is shown in blue) | |

| Details | |

| Origin | The middle 1/2 of the anterior surface of the radius and the adjacent interosseus membrane. |

| Insertion | The base of the distal phalanx of the thumb |

| Artery | Anterior interosseous artery |

| Nerve | Anterior interosseous nerve (branch of median nerve) (C8, T1) |

| Actions | Flexion of the thumb. |

| Antagonist | Extensor pollicis longus muscle, Extensor pollicis brevis muscle |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Musculus flexor pollicis longus |

| TA98 | A04.6.02.037 |

| TA2 | 2492 |

| FMA | 38481 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

Human anatomy

Origin and insertion

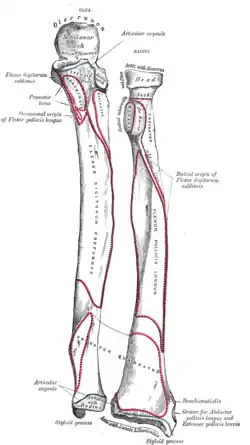

It arises from the grooved anterior (side of palm) surface of the body of the radius,[3] extending from immediately below the radial tuberosity and oblique line to within a short distance of the pronator quadratus muscle.[4] An occasionally present accessory long head of the flexor pollicis longus muscle is called 'Gantzer's muscle'.[5] It may cause compression of the anterior interosseous nerve.[5]

It arises also from the adjacent part of the interosseous membrane of the forearm, and generally by a fleshy slip from the medial border of the coronoid process of the ulna.[4] In 40 percent of cases, it is also inserted from the medial epicondyle of the humerus, and in those cases a tendinous connection with the humeral head of the flexor digitorum superficialis is present.[6]

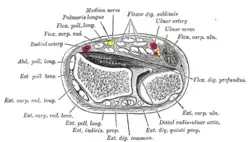

The fibers end in a flattened tendon, which passes beneath the flexor retinaculum of the hand through the carpal tunnel. It is then lodged between the lateral head of the flexor pollicis brevis and the oblique part of the adductor pollicis, and, entering an osseoaponeurotic canal similar to those for the flexor tendons of the fingers, is inserted into the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb.[4]

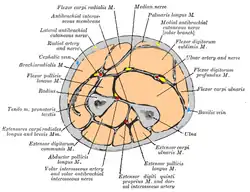

Relations

The anterior interosseous nerve (a branch of the median nerve) and the anterior interosseous artery and vein pass downward on the front of the interosseous membrane between the flexor pollicis longus and flexor digitorum profundus.[4]

Injuries to tendons are particularly difficult to recover from due to the limited blood supply they receive.

Actions

The flexor pollicis longus is a flexor of the phalanges of the thumb; when the thumb is fixed, it assists in flexing the wrist.[4]

Innervation

The flexor pollicis longus is supplied by the anterior interosseous(C8-T1) branch of the median nerve (C5-T1).[7][8]

Variations

Slips may connect with flexor digitorum superficialis muscle, flexor digitorum profundus muscle (resulting in the Linburg-Comstock syndrome),[9] or the pronator teres muscle. An additional tendon to the index finger is sometimes found.[4]

Evolutionary variation

Modern humans are unique among hominids in having a flexor pollicis longus (FPL) muscle belly that is separate from that of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP). While the FPL is not a separate muscle belly in extant great apes, a distinct tendon from the FDP belly might be present. In some individuals, this tendon tend to act more like a ligament, which restricts extension of the interphalangeal joint of the thumb. In orangutans there is a tendon similar in insertion and function to the FPL in humans, but which has an intrinsic origin on the oblique head of the adductor pollicis.[10]

Lesser apes (i.e. gibbons) and Old World monkeys (e.g. baboons) share an extrinsic FPL muscle tendon with humans. In most lesser apes, the FPL belly is separate from the FDP belly, but in baboons, the FPL tendon bifurcates from the FDP tendon at the wrist within the carpal tunnel and, because of the lack of differentiation in both the FDP and FPL musculature, it is unlikely that baboons can control individual digits independently.[10]

Additional images

Bones of left forearm. Anterior aspect.

Bones of left forearm. Anterior aspect. Bones of the left hand. Volar surface.

Bones of the left hand. Volar surface. Cross-section through the middle of the forearm.

Cross-section through the middle of the forearm. Transverse section across distal ends of radius and ulna.

Transverse section across distal ends of radius and ulna. Transverse section across the wrist and digits.

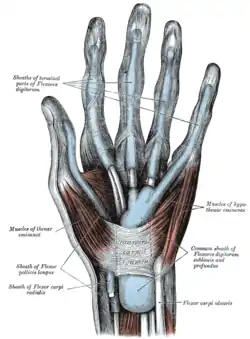

Transverse section across the wrist and digits. The mucous sheaths of the tendons on the front of the wrist and digits.

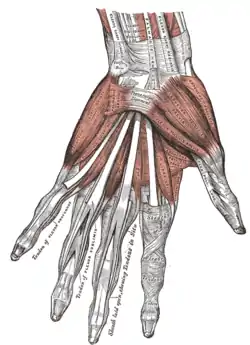

The mucous sheaths of the tendons on the front of the wrist and digits. The muscles of the left hand. Palmar surface.

The muscles of the left hand. Palmar surface. Ulnar and radial arteries. Deep view.

Ulnar and radial arteries. Deep view. Nerves of the left upper extremity.

Nerves of the left upper extremity. Flexor pollicis longus muscle

Flexor pollicis longus muscle Flexor pollicis longus muscle

Flexor pollicis longus muscle Flexor pollicis longus muscle

Flexor pollicis longus muscle Flexor pollicis longus muscle

Flexor pollicis longus muscle Flexor pollicis longus muscle

Flexor pollicis longus muscle

Reference

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 449 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 449 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Straus WL (September 1942). "Rudimentary Digits in Primates". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 17 (3): 228–43. doi:10.1086/394656. JSTOR 2809086. S2CID 85312042.

- Asghar, Adil; Jha, Rakesh Kumar; Patra, Apurba; Chaudhary, Binita; Singh, Brijendra (0000). "The prevalence and distribution of the variants of Gantzer's muscle: a meta-analysis of cadaveric studies". Anatomy & Cell Biology. doi:10.5115/acb.21.141.

- Fernandez DL (2009-01-01). "Chapter 56: Osteotomy for Extra-articular Malunion of the Distal Radius". In Slutsky DJ, Osterman AL (eds.). Fractures and Injuries of the Distal Radius and Carpus. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 529–541. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4160-4083-5.00058-5. ISBN 978-1-4160-4083-5.

- Gray 1918, Flexor Pollicis Longus, paras 20, 25

- Caetano EB, Sabongi JJ, Vieira LÂ, Caetano MF, Moraes DV (2015). "Gantzer muscle. An anatomical study". Acta Ortopedica Brasileira. 23 (2): 72–5. doi:10.1590/1413-78522015230200955. PMC 4813407. PMID 27069404.

- Platzer 2004, p 162

- Lutsky KF, Giang EL, Matzon JL (January 2015). "Flexor tendon injury, repair and rehabilitation". The Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 46 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2014.09.004. PMID 25435036.

- Preston DC, Shapiro BE (2013-01-01). "Chapter 18: Proximal Median Neuropathy". In Preston (ed.). Electromyography and Neuromuscular Disorders (Third ed.). pp. 289–297.

- Hamitouche K, Roux JL, Baeten Y, Allieu Y (May 2000). "[Linburg-Comstock syndrome. Epidemiologic and anatomic study, clinical applications]". Chirurgie de la Main. 19 (2): 109–15. doi:10.1016/s1297-3203(00)73468-8. PMID 10904829.

- Tocheri MW, Orr CM, Jacofsky MC, Marzke MW (April 2008). "The evolutionary history of the hominin hand since the last common ancestor of Pan and Homo". Journal of Anatomy. 212 (4): 544–62. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00865.x. PMC 2409097. PMID 18380869.

Further reading

- Gray H (1918). "The Muscles and Fasciæ of the Forearm". Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body. Archived from the original on 2012-01-23. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- Platzer W (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- Tocheri MW, Orr CM, Jacofsky MC, Marzke MW (April 2008). "The evolutionary history of the hominin hand since the last common ancestor of Pan and Homo". Journal of Anatomy. 212 (4): 544–62. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00865.x. PMC 2409097. PMID 18380869.