Supraspinatus muscle

The supraspinatus (plural supraspinati) is a relatively small muscle of the upper back that runs from the supraspinous fossa superior portion of the scapula (shoulder blade) to the greater tubercle of the humerus. It is one of the four rotator cuff muscles and also abducts the arm at the shoulder. The spine of the scapula separates the supraspinatus muscle from the infraspinatus muscle, which originates below the spine.

| Supraspinatus muscle | |

|---|---|

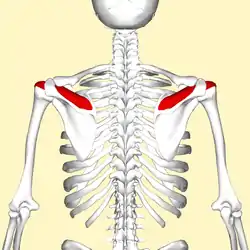

Position of the supraspinatus muscle (red) seen from the back. | |

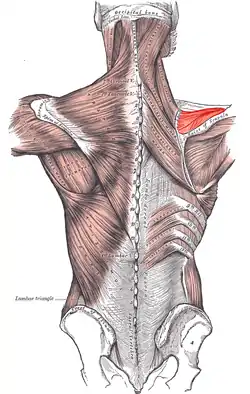

Posterior view of muscles connecting the upper extremity to the vertebral column. Supraspinatus muscle is labeled in red at right, while it is covered by other muscles at left. | |

| Details | |

| Origin | supraspinous fossa of scapula |

| Insertion | superior facet of greater tubercle of humerus |

| Artery | suprascapular artery |

| Nerve | suprascapular nerve |

| Actions | abduction of arm and stabilizes humerus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus supraspinatus |

| TA98 | A04.6.02.006 |

| TA2 | 2457 |

| FMA | 9629 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

Structure

The supraspinatus muscle arises from the supraspinous fossa, a shallow depression in the body of the scapula above its spine. The supraspinatus muscle tendon passes laterally beneath the cover of the acromion. Research in 1996 showed that the postero-lateral origin was more lateral than classically described.[1][2]

The supraspinatus tendon is inserted into the superior facet of the greater tubercle of the humerus.[3] The distal attachments of the three rotator cuff muscles that insert into the greater tubercle of the humerus can be abbreviated as SIT when viewed from superior to inferior (for supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor), or SITS when the subscapularis muscle, which attaches to the lesser tubercle of the humerus, is included.[4]

Nerve supply

The suprascapular nerve (C5) innervates the supraspinatus muscle as well as the infraspinatus muscle. It comes from the upper trunk of the brachial plexus. This nerve can be damaged along its course in fractures of the overlying clavicle, which can reduce the person's ability to initiate the abduction.

Function

The supraspinatus muscle performs abduction of the arm, and pulls the head of the humerus medially towards the glenoid cavity.[5] It independently prevents the head of the humerus from slipping inferiorly.[5] The supraspinatus works in cooperation with the deltoid muscle to perform abduction, including when the arm is in an adducted position.[5] Beyond 15 degrees the deltoid muscle becomes increasingly more effective at abducting the arm and becomes the main propagator of this action.[6]

Clinical significance

The supraspinatus forms part of the rotator cuff and is one of its most frequently damaged components, whether from acute injury or gradual degeneration.[7] Bad posture and age are leading risk factors, with a high prevalence of unsymptomatic partial and full tears, as well as symptomatic syndromes with chronic pain. Connected pathologies include acromial impingement, frozen shoulder, and poor sleep, especially on the side. Both ultrasound and MRI are now effective methods of diagnosis.

Tear

- Diagnosis

Antero-posterior projectional radiography of the shoulder may demonstrate a high-riding humeral head, with an acromiohumeral distance of less than 7 mm.[8]

- Repair

One study has indicated that arthroscopic surgery for full-thickness supraspinatus tears is effective for improving shoulder functionality.[9]

A comparative effectiveness review of nonoperative and operative treatments for rotator cuff tears was performed at the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center in 2010. The review identified one study which reported that, "Patients receiving early surgery had superior function compared with the delayed surgical group". The review noted that the level of significance of the study was not reported, and the review chose not to include it as one of their conclusions. Instead it concluded that "The paucity of evidence related to early versus delayed surgery is of particular concern, as patients and providers must decide whether to attempt initial nonoperative management or proceed immediately with surgical repair". In terms of operative techniques, differences in neither cuff integrity nor shoulder function were reported in studies comparing single-row versus double-row suture anchor fixation and mattress locking versus absorbable sutures. Postoperatively, a slight advantage was evident in patients who performed continuous passive motion alongside physical therapy, as opposed to those who solely performed physical therapy. There is insufficient evidence to adequately compare the effects of operative against nonoperative interventions. Complications were reported very seldom, or were not determined to be clinically significant.[10]

A 2016 study evaluating the effectiveness of arthroscopic treatment of rotator cuff calcification firmly supported surgical intervention. Calcification of the supraspinatus tendon is a major contributor to shoulder pain in the general population and is often worsened following a supraspinatus tear. The results of the study included the return to sports and original functionality of 95.8% of the patients after a mean of 5.3 post-operative months. A significant decrease in pain was observed over time following removal of the calcification. The study showed the overall effectiveness of arthroscopic procedures on shoulder repair, and the lack of risk experienced.[11] Before surgery, supraspinatus tendonitis should be ruled out as the cause of pain.

Additional images

Position of the supraspinatus muscle (shown in red). Animation.

Position of the supraspinatus muscle (shown in red). Animation. Muscles around the left shoulder, seen from behind.

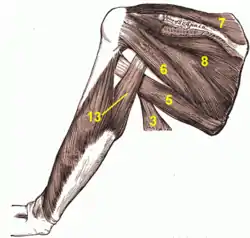

Muscles around the left shoulder, seen from behind.

3. Latissimus dorsi muscle

5. Teres major muscle

6. Teres minor muscle

7. Supraspinatus muscle

8. Infraspinatus muscle

13. long head of Triceps brachii muscle..gif) Action of right supraspinatus muscle, anterior view. Three bones shown are acromion (top) and coracoid process (center) of scapula, and humerus (left).

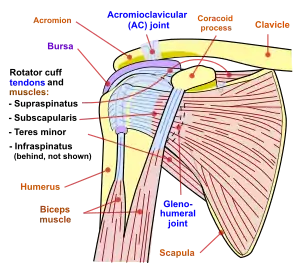

Action of right supraspinatus muscle, anterior view. Three bones shown are acromion (top) and coracoid process (center) of scapula, and humerus (left). Diagram of the human shoulder joint, front view

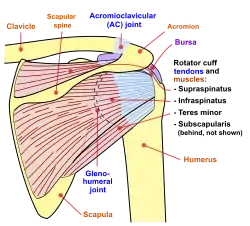

Diagram of the human shoulder joint, front view Diagram of the human shoulder joint, back view

Diagram of the human shoulder joint, back view

References

- Thomazeau, H.; Duval, J. M.; Darnault, P.; Dréano, T. (1996). "Anatomical relationships and scapular attachments of the supraspinatus muscle". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 18 (3): 221–5. doi:10.1007/BF02346130. PMID 8873337. S2CID 1657973.

- D.F. Gazielly, P. Gleyze & T. Thomas, 1996, "The Cuff," Elsevier, ISBN 2906077844, see , accessed 21 November 2014.

- "Injured Shoulder". Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- MedicalMnemonics.com: 35

- David G. Simons; Janet G. Travell; Lois S. Simons (1999). Travell & Simons' Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: Upper half of body. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 541–. ISBN 978-0-683-08363-7.

- Drake & Vogl & Mitchell (2014-04-03). Gray´s Anatomy for students 3rd edition. Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 9780702051319.

- Sambandam, Senthil Nathan; Khanna, Vishesh; Gul, Arif; Mounasamy, Varatharaj (December 18, 2015). "Rotator cuff tears: An evidence based approach". World Journal of Orthopedics. 6 (11): 902–918. doi:10.5312/wjo.v6.i11.902. PMC 4686437. PMID 26716086 – via PubMed.

- Moosikasuwan JB, Miller TT, Burke BJ (2005). "Rotator cuff tears: clinical, radiographic, and US findings". Radiographics. 25 (6): 1591–607. doi:10.1148/rg.256045203. PMID 16284137.

- Bennett, William F. (21 October 2014). "Arthroscopic Supraspinatus Repair". Bennett Orthopedics & Sportsmedicine. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- Seida J, Schouten J, Mousavi S, Tjosvold L, Vandermeer B, Milne A, Bond K, Hartling L, LeBlanc C, Sheps D. Comparative Effectiveness of Nonoperative and Operative Treatment for Rotator Cuff Tears. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 22. (Prepared by the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0023.) AHRQ Publication No. 10-EHC050. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. July 2010. Available at: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm.

- Ranalletta M, Rossi LA, Sirio A, Bruchmann G, Maignon GD, Bongiovanni SL (October 2016). "Return to Sports After Arthroscopic Treatment of Rotator Cuff Calcifications in Athletes". Orthop J Sports Med. 4 (10): 2325967116669310. doi:10.1177/2325967116669310. PMC 5084521. PMID 27826596.