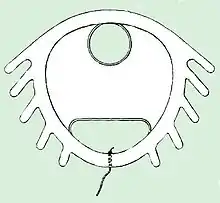

Dalkon Shield

The Dalkon Shield was a contraceptive intrauterine device (IUD) developed by the Dalkon Corporation and marketed by the A.H. Robins Company. The Dalkon Shield was found to cause severe injury to a disproportionately large percentage of women, which eventually led to numerous lawsuits, in which juries awarded millions of dollars in compensatory and punitive damages.

History

In 1970, the A.H. Robins Company acquired the Dalkon Shield from the Dalkon Corporation, founded by Hugh J. Davis, M.D. The Dalkon Corporation had only four shareholders: the inventors Davis and Irwin Lerner,[1] their attorney Robert Cohn, and Thad J. Earl, M.D., a medical practitioner in Defiance, Ohio. In 1971, Dalkon Shield went into the market, beginning in the United States and Puerto Rico, spearheaded by a large marketing campaign. At its peak, about 2.8 million women used the Dalkon Shield in the U.S.

At the time of its introduction, the Dalkon Shield was promoted as a safer alternative compared to birth control pills, which at the time were the subject of many safety concerns.[1] Dr. Davis himself was a participant in the Nelson hearings, which were congressional hearings led by Senator Gaylord Nelson regarding the safety of oral contraceptives. He asserted that oral contraceptives with high doses of hormones were dangerous and that the efficacy of the pill was "greatly overrated."[2]

Initial reports in the medical literature raised questions about whether its efficacy in preventing pregnancy and expulsion rate were as good as those claimed by the manufacturer, but failed to detect the tendency of the device to cause septic abortion and other severe infections.[3]

In June 1973, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted a survey of 34,544 physicians with practices in gynecology or obstetrics regarding women who had been hospitalized or had died with complications related to the use of an IUD in the previous 6 months. A total of 16,994 physicians responded, yielding 3,502 unique case reports of women hospitalized in the first 6 months of 1973. Based on the survey response rate, the CDC estimated that a total of 7,900 IUD related hospitalizations occurred during this 6-month period. Based on an estimate of 3.2 million IUD users, the CDC estimated an annual device-related hospitalization rate of 5 per 1000 IUD users. The survey also provided 5 reports of device-related fatalities, with four of these related to severe infection. One of the five was associated with the Dalkon Shield. Based on these data, the CDC estimated an IUD-related fatality rate of 3 per million users per year of use, which it compared favorably to the mortality risks associated with pregnancy and other forms of contraception. Importantly, the survey showed that the Dalkon Shield was associated with an increased rate of pregnancy-associated complications leading to hospitalization.[4]

By 1974, approximately 2.5 million women had received the Dalkon intrauterine device. In June of that year, the medical director of A.H. Robins published a letter to the editor of the British Medical Journal stating that the company was aware of an "apparent increase in the number of cases of septic abortions" including 4 fatalities, but stating that "there is no evidence of a direct cause-and-effect relationship between wearing of the Dalkon Shield and the occurrence of septicemia". The letter recommended precautions including pregnancy tests for women who missed their period and immediate removal of the device in women who were found to be pregnant.[5] In October 1974, a series of four case reports of septic pregnancies was published in the journal Obstretics and Gynecology".[6] In 1975, the CDC published a study associating the Dalkon Shield with a higher risk of spontaneous abortion-related death compared to other IUDs.[7]

As many as 200,000 women made claims against the A.H. Robins company, mostly related to claims associated with pelvic inflammatory disease and loss of fertility. The company eventually filed for bankruptcy. The company's representatives argued that pelvic infections have a wide variety of causes, and that the Dalkon Shield was no more dangerous than other forms of birth control. Lawyers for the plaintiffs argued that the women they represented would be healthy and fertile today if not for the device. Scientists from the CDC stated that both arguments have merit.[8]

Aftermath

More than 300,000 lawsuits were filed against the A.H. Robins Company – the largest tort liability case since asbestos. The federal judge, Miles W. Lord, attracted public commentary for his judgments, impositions of personal liability, and public rebukes of the company heads.[9] The cost of litigation and settlements (estimated at billions of dollars) led the company to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 1985. As a result, Robins sold the company to American Home Products (now Wyeth).

In 1976, the Medical Device Amendments to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act mandated the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, for the first time, to require testing and approval of "medical devices", including IUDs.[10]

The Dalkon Shield became infamous for its serious design flaw: a porous, multifilament string upon which bacteria could travel into the uterus of users, leading to sepsis, injury, miscarriage, and death. Modern intrauterine devices (IUDs) use monofilament strings, which do not pose this grave risk to users.

References

- Robert McG., Thomas Jr. (October 26, 1996). "Hugh J. Davis, 69, Gynecologist Who Invented Dalkon Shield". The New York Times. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- United States (1967). Competitive problems in the drug industry: hearings before Subcommittee on Monopoly of the Select Committee on Small Business, United States Senate, Ninetieth Congress, first session ... Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

- Jones, R.W.; Parker, A.; Elstein, Max (1973). "Clinical experience with the Dalkon Shield intrauterine device". Br Med J. 3 (5872): 143–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.3.5872.143. PMC 1586323. PMID 4720765.

- CDC (October 17, 1997). "Current trends IUD safety: report of a nationwide physician survey". MMWR. 46 (41): 969–974.

- Templeton, J.S. (1974). "Letter: septic abortion and the Dalkon Shield". Br Med J. 2 (5919): 612. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5919.612. PMC 1610760. PMID 4833976.

- Hurt, W.G. (1974). "Septic pregnancy associated with Dalkon Shield intrauterine device". Obstet Gynecol. 44 (4): 491–5. PMID 4607058.

- Cates, W.; Ory, H.W.; Rochat, R.W.; Tyler, C.W. (1976). "The intrauterine device and deaths from spontaneous abortion". N. Engl. J. Med. 295 (21): 1155–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM197611182952102. PMID 980018.

- Kolata, Gina (December 6, 1987). "The sad legacy of the Dalkon Shield". The New York Times.

- Serrill, Michael S. (July 23, 1984). "A Panel Tries to Judge a Judge". Time. Archived from the original on October 29, 2010.

- Adler, Robert (1988). "The 1976 Medical Device Amendments: A Step in the Right Direction Needs Another Step in the Right Direction". Food, Drug, Cosmetic Law Journal. 43 (3): 511–532. ISSN 0015-6361. JSTOR 26658558.

Bibliography

- Szaller, Jim (Winter 1999). "One Lawyer's 25 Year Journey: The Dalkon Shield Saga". Ohio Trial. 9 (4). Archived from the original (Reprint) on 2006-05-13. Retrieved 2006-08-17. – Chronicles legal team of Brown & Szaller's involvement in the Dalkon Shield Litigation.

- Speroff, L.; Glass, R.H.; Kase, N.G. (1999). Clinical Gynecological Endocrinology and Infertility (6th ed.). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. p. 976. ISBN 978-0-683-30379-7.

- Gordon, Meryl (February 20, 1999). "A Cash Settlement, But No Apology". New York Times. Retrieved 2006-08-17.

- Sivin, I. (1993). "Another look at the Dalkon Shield: meta-analysis underscores its problems". Contraception. 48 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(93)90060-k. PMID 8403900.

- Anselmi, Katherine Kaby (1994). "Women's response to reproductive trauma secondary to contraceptive iatrogenesis: A phenomenological approach to the Dalkon Shield case" (Abstract): 1–226.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) – Dissertation - "Robins Plan Is Approved". New York Times. Associated Press. June 17, 1989.

- Shereff, Ruth (February 13, 1989). "How to Reward The Criminals". The Nation. 248 (6).

Books

- Bacigal, Ronald J. (1990). The Limits Of Litigation: The Dalkon Shield Controversy. Durham, N.C.: Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 0890893918.

- Engelmayer, Sheldon D. (1985-09-22). "Lord's Justice : One Judge's War Against the Infamous Dalkon Shield" (New York Times Review). The New York Times. New York. ISBN 978-0-385-23051-3. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- Grant, Nicole J. (1992). The Selling of contraception : the Dalkon Shield case, sexuality, and women's autonomy. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0814205723.

- Hawkins, Mary E. (1997). Unshielded: The Human Cost Of The Dalkon Shield. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802008763.

- Hicks, Karen M. (1994). Surviving The Dalkon Shield Iud : Women v. The Pharmaceutical Industry. New York: Teachers College Press. ISBN 0807762717.

- Mintz, Morton (1985). At Any Cost: Corporate Greed, Women, And The Dalkon Shield. New York: Pantheon. ISBN 0394548469.

- Abstract: Morton Mintz (January 15, 1986). "A Crime Against Women: A.H. Robins and the Dalkon Shield". Multimedia Monitor. 7 (1). – Includes full text of presiding judge Miles Lord's statement to Clairbone Robins, et al., at bottom.

- Reviewed and summarised by: Tamar Lewin (1986-01-12). "What Standards For Corporate Crime?". New York Times.

- Perry, Susan & Dawson, Jim (1985). Nightmare: Women And The Dalkon Shield. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0025959301.

- Sobol, Richard B. (1991). Bending The Law: The Story Of The Dalkon Shield Bankruptcy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226767523.

- Stern, Gerald M. (1976). The Buffalo Creek Disaster. New York: Random House. ISBN 0394403908.