Arthritis

Arthritis is a term often used to mean any disorder that affects joints.[2] Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness.[2] Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints.[2][3] In some types of arthritis, other organs are also affected.[6] Onset can be gradual or sudden.[5]

| Arthritis | |

|---|---|

| |

| A hand affected by rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune form of arthritis | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Symptoms | Joint pain, stiffness, redness, swelling, decreased range of motion[2][3] |

| Types | > 100, most common (osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis)[4][5][6] |

| Risk factors | Family history, age, sex trait, previous joint injury, obesity.[7] |

| Treatment | Resting, applying ice or heat, weight loss, exercise, joint replacement[6] |

| Medication | Ibuprofen, paracetamol (acetaminophen)[8] |

There are over 100 types of arthritis.[9][4][5] The most common forms are osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease) and rheumatoid arthritis.[6] Osteoarthritis usually occurs with age and affects the fingers, knees, and hips.[10][6] Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disorder that often affects the hands and feet.[6] Other types include gout, lupus, fibromyalgia, and septic arthritis.[6][11] They are all types of rheumatic disease.[2]

Treatment may include resting the joint and alternating between applying ice and heat.[12][6] Weight loss and exercise may also be useful.[13][6] Recommended medications may depend on the form of arthritis.[14][8] These may include pain medications such as ibuprofen and paracetamol (acetaminophen).[8] In some circumstances, a joint replacement may be useful.[6]

Osteoarthritis affects more than 3.8% of people, while rheumatoid arthritis affects about 0.24% of people.[15] Gout affects about 1–2% of the Western population at some point in their lives.[16] In Australia about 15% of people are affected by arthritis,[17] while in the United States more than 20% have a type of arthritis.[11][18] Overall the disease becomes more common with age.[11] Arthritis is a common reason that people miss work and can result in a decreased quality of life.[8] The term is derived from arthr- (meaning 'joint') and -itis (meaning 'inflammation').[19][20]

Classification

There are several diseases where joint pain is primary, and is considered the main feature. Generally when a person has "arthritis" it means that they have one of these diseases, which include:

- Osteoarthritis[21]

- Rheumatoid arthritis[22]

- Gout and pseudo-gout[23]

- Septic arthritis[24]

- Ankylosing spondylitis[25]

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis[26]

- Still's disease[27]

- Psoriatic arthritis[28]

Joint pain can also be a symptom of other diseases. In this case, the arthritis is considered to be secondary to the main disease; these include:

- Psoriasis[29]

- Reactive arthritis[30]

- Ehlers–Danlos syndrome[31]

- Iron overload[32]

- Hepatitis[33][34]

- Lyme disease[35]

- Sjögren's disease[36]

- Hashimoto's thyroiditis[37]

- Celiac disease[38]

- Non-celiac gluten sensitivity[39][40][41]

- Inflammatory bowel disease (including Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis)[42][43]

- Henoch–Schönlein purpura[44]

- Hyperimmunoglobulinemia D with recurrent fever

- Sarcoidosis[45]

- Whipple's disease[46]

- TNF receptor associated periodic syndrome[47]

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (and many other vasculitis syndromes)

- Familial Mediterranean fever[48]

- Systemic lupus erythematosus[49]

An undifferentiated arthritis is an arthritis that does not fit into well-known clinical disease categories, possibly being an early stage of a definite rheumatic disease.[50]

Signs and symptoms

| Extra-articular features of joint disease[51] |

|---|

| Cutaneous nodules |

| Cutaneous vasculitis lesions |

| Lymphadenopathy |

| Oedema |

| Ocular inflammation |

| Urethritis |

| Tenosynovitis (tendon sheath effusions) |

| Bursitis (swollen bursa) |

| Diarrhea |

| Orogenital ulceration |

Pain, which can vary in severity, is a common symptom in virtually all types of arthritis.[52][53] Other symptoms include swelling, joint stiffness, redness, and aching around the joint(s).[2] Arthritic disorders like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis can affect other organs in the body, leading to a variety of symptoms.[11] Symptoms may include:[2]

- Inability to use the hand or walk

- Stiffness in one or more joints

- Rash or itch

- Malaise and fatigue

- Weight loss

- Poor sleep

- Muscle aches and pains

- Tenderness

- Difficulty moving the joint

It is common in advanced arthritis for significant secondary changes to occur. For example, arthritic symptoms might make it difficult for a person to move around and/or exercise, which can lead to secondary effects, such as:

- Muscle weakness

- Loss of flexibility

- Decreased aerobic fitness

These changes, in addition to the primary symptoms, can have a huge impact on quality of life.

Disability

Arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the United States. More than 20 million individuals with arthritis have severe limitations in function on a daily basis.[11] Absenteeism and frequent visits to the physician are common in individuals who have arthritis. Arthritis can make it difficult for individuals to be physically active and some become home bound.

It is estimated that the total cost of arthritis cases is close to $100 billion of which almost 50% is from lost earnings. Each year, arthritis results in nearly 1 million hospitalizations and close to 45 million outpatient visits to health care centers.[54]

Decreased mobility, in combination with the above symptoms, can make it difficult for an individual to remain physically active, contributing to an increased risk of obesity, high cholesterol or vulnerability to heart disease.[55] People with arthritis are also at increased risk of depression, which may be a response to numerous factors, including fear of worsening symptoms.[56]

Risk factors

There are common risk factors that increase a person's chance of developing arthritis later in adulthood. Some of these are modifiable while others are not.[57] Smoking has been linked to an increased susceptibility of developing arthritis, particularly rheumatoid arthritis.[58]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by clinical examination from an appropriate health professional, and may be supported by other tests such as radiology and blood tests, depending on the type of suspected arthritis.[59] All arthritides potentially feature pain. Pain patterns may differ depending on the arthritides and the location. Rheumatoid arthritis is generally worse in the morning and associated with stiffness lasting over 30 minutes.[60] However, in the early stages, patients may have no symptoms after a warm shower. Osteoarthritis, on the other hand, tends to be associated with morning stiffness which eases relatively quickly with movement and exercise. In the aged and children, pain might not be the main presenting feature; the aged patient simply moves less, the infantile patient refuses to use the affected limb.

Elements of the history of the disorder guide diagnosis. Important features are speed and time of onset, pattern of joint involvement, symmetry of symptoms, early morning stiffness, tenderness, gelling or locking with inactivity, aggravating and relieving factors, and other systemic symptoms. Physical examination may confirm the diagnosis or may indicate systemic disease. Radiographs are often used to follow progression or help assess severity.

Blood tests and X-rays of the affected joints often are performed to make the diagnosis. Screening blood tests are indicated if certain arthritides are suspected. These might include: rheumatoid factor, antinuclear factor (ANF), extractable nuclear antigen, and specific antibodies.

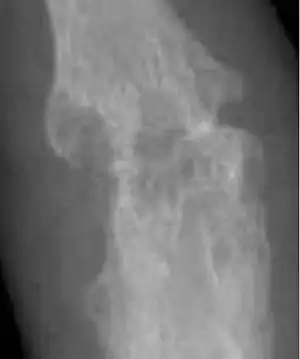

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis.[61] It affects humans and other animals, notably dogs, but also occurs in cats and horses. It can affect both the larger and the smaller joints of the body. In humans, this includes the hands, wrists, feet, back, hip, and knee. In dogs, this includes the elbow, hip, stifle (knee), shoulder, and back. The disease is essentially one acquired from daily wear and tear of the joint; however, osteoarthritis can also occur as a result of injury. Osteoarthritis begins in the cartilage and eventually causes the two opposing bones to erode into each other. The condition starts with minor pain during physical activity, but soon the pain can be continuous and even occur while in a state of rest. The pain can be debilitating and prevent one from doing some activities. In dogs, this pain can significantly affect quality of life and may include difficulty going up and down stairs, struggling to get up after lying down, trouble walking on slick floors, being unable to hop in and out of vehicles, difficulty jumping on and off furniture, and behavioral changes (e.g., aggression, difficulty squatting to toilet).[62] Osteoarthritis typically affects the weight-bearing joints, such as the back, knee and hip. Unlike rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis is most commonly a disease of the elderly. The strongest predictor of osteoarthritis is increased age, likely due to the declining ability of chondrocytes to maintain the structural integrity of cartilage.[63] More than 30 percent of women have some degree of osteoarthritis by age 65. Other risk factors for osteoarthritis include prior joint trauma, obesity, and a sedentary lifestyle.[64]

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a disorder in which the body's own immune system starts to attack body tissues.[66] The attack is not only directed at the joint but to many other parts of the body. In rheumatoid arthritis, most damage occurs to the joint lining and cartilage which eventually results in erosion of two opposing bones. RA often affects joints in the fingers, wrists, knees and elbows, is symmetrical (appears on both sides of the body), and can lead to severe deformity in a few years if not treated. RA occurs mostly in people aged 20 and above. In children, the disorder can present with a skin rash, fever, pain, disability, and limitations in daily activities.[67] With earlier diagnosis and aggressive treatment, many individuals can lead a better quality of life than if going undiagnosed for long after RA's onset.[68] The risk factors with the strongest association for developing rheumatoid arthritis are the female sex, a family history of rheumatoid arthritis, age, obesity, previous joint damage from an injury, and exposure to tobacco smoke.[69][70]

Bone erosion is a central feature of rheumatoid arthritis. Bone continuously undergoes remodeling by actions of bone resorbing osteoclasts and bone forming osteoblasts. One of the main triggers of bone erosion in the joints in rheumatoid arthritis is inflammation of the synovium, caused in part by the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL), a cell surface protein present in Th17 cells and osteoblasts.[71] Osteoclast activity can be directly induced by osteoblasts through the RANK/RANKL mechanism.[72]

Lupus

Lupus is a common collagen vascular disorder that can be present with severe arthritis. Other features of lupus include a skin rash, extreme photosensitivity, hair loss, kidney problems, lung fibrosis and constant joint pain.[73]

Gout

Gout is caused by deposition of uric acid crystals in the joints, causing inflammation. There is also an uncommon form of gouty arthritis caused by the formation of rhomboid crystals of calcium pyrophosphate known as pseudogout. In the early stages, the gouty arthritis usually occurs in one joint, but with time, it can occur in many joints and be quite crippling. The joints in gout can often become swollen and lose function. Gouty arthritis can become particularly painful and potentially debilitating when gout cannot successfully be treated.[74] When uric acid levels and gout symptoms cannot be controlled with standard gout medicines that decrease the production of uric acid (e.g., allopurinol) or increase uric acid elimination from the body through the kidneys (e.g., probenecid), this can be referred to as refractory chronic gout.[75]

Comparison of types

| Osteoarthritis | Rheumatoid arthritis | Gouty arthritis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed of onset | Months | Weeks-months[77] | Hours for an attack[78] |

| Main locations | Weight-bearing joints (such as knees, hips, vertebral column) and hands | Hands (proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joint) wrists, ankles, knees and hips | Great toe, ankles, knees and elbows |

| Inflammation | May occur, though often mild compared to inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis | Yes | Yes |

| Radiologic changes |

|

|

|

| Laboratory findings | None | Anemia, elevated ESR and C-reactive protein (CRP), rheumatoid factor, anti-citrullinated protein antibody | Crystal in joints |

| Other features |

|

|

Other

Infectious arthritis is another severe form of arthritis. It presents with sudden onset of chills, fever and joint pain. The condition is caused by bacteria elsewhere in the body. Infectious arthritis must be rapidly diagnosed and treated promptly to prevent irreversible joint damage.[79]

Psoriasis can develop into psoriatic arthritis. With psoriatic arthritis, most individuals develop the skin problem first and then the arthritis. The typical features are continuous joint pains, stiffness and swelling. The disease does recur with periods of remission but there is no cure for the disorder. A small percentage develop a severely painful and destructive form of arthritis which destroys the small joints in the hands and can lead to permanent disability and loss of hand function.[80]

Treatment

There is no known cure for arthritis and rheumatic diseases. Treatment options vary depending on the type of arthritis and include physical therapy, exercise and diet, orthopedic bracing, and oral and topical medications.[2][81] Joint replacement surgery may be required to repair damage, restore function, or relieve pain.[2]

Physical therapy

In general, studies have shown that physical exercise of the affected joint can noticeably improve long-term pain relief. Furthermore, exercise of the arthritic joint is encouraged to maintain the health of the particular joint and the overall body of the person.[82]

Individuals with arthritis can benefit from both physical and occupational therapy. In arthritis the joints become stiff and the range of movement can be limited. Physical therapy has been shown to significantly improve function, decrease pain, and delay the need for surgical intervention in advanced cases.[83] Exercise prescribed by a physical therapist has been shown to be more effective than medications in treating osteoarthritis of the knee. Exercise often focuses on improving muscle strength, endurance and flexibility. In some cases, exercises may be designed to train balance. Occupational therapy can provide assistance with activities. Assistive technology is a tool used to aid a person's disability by reducing their physical barriers by improving the use of their damaged body part, typically after an amputation. Assistive technology devices can be customized to the patient or bought commercially.[84]

Medications

There are several types of medications that are used for the treatment of arthritis. Treatment typically begins with medications that have the fewest side effects with further medications being added if insufficiently effective.[85]

Depending on the type of arthritis, the medications that are given may be different. For example, the first-line treatment for osteoarthritis is acetaminophen (paracetamol) while for inflammatory arthritis it involves non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen. Opioids and NSAIDs may be less well tolerated.[86] However, topical NSAIDs may have better safety profiles than oral NSAIDs. For more severe cases of osteoarthritis, intra-articular corticosteroid injections may also be considered.[87]

The drugs to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA) range from corticosteroids to monoclonal antibodies given intravenously. Due to the autoimmune nature of RA, treatments may include not only pain medications and anti-inflammatory drugs, but also another category of drugs called disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Treatment with DMARDs is designed to slow down the progression of RA by initiating an adaptive immune response, in part by CD4+ T helper (Th) cells, specifically Th17 cells.[88] Th17 cells are present in higher quantities at the site of bone destruction in joints and produce inflammatory cytokines associated with inflammation, such as interleukin-17 (IL-17).[71]

Surgery

A number of rheumasurgical interventions have been incorporated in the treatment of arthritis since the 1950s. Arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee provides no additional benefit to optimized physical and medical therapy.[89]

Adaptive aids

People with hand arthritis can have trouble with simple activities of daily living tasks (ADLs), such as turning a key in a lock or opening jars, as these activities can be cumbersome and painful. There are adaptive aids or assistive devices (ADs) available to help with these tasks,[90] but they are generally more costly than conventional products with the same function. It is now possible to 3-D print adaptive aids, which have been released as open source hardware to reduce patient costs.[91][92] Adaptive aids can significantly help arthritis patients and the vast majority of those with arthritis need and use them.[93]

Alternative medicine

Further research is required to determine if transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for knee osteoarthritis is effective for controlling pain.[94]

Low level laser therapy may be considered for relief of pain and stiffness associated with arthritis.[95] Evidence of benefit is tentative.[96]

Pulsed electromagnetic field therapy (PEMFT) has tentative evidence supporting improved functioning but no evidence of improved pain in osteoarthritis.[97] The FDA has not approved PEMFT for the treatment of arthritis. In Canada, PEMF devices are legally licensed by Health Canada for the treatment of pain associated with arthritic conditions.[98]

Epidemiology

Arthritis is predominantly a disease of the elderly, but children can also be affected by the disease.[99] Arthritis is more common in women than men at all ages and affects all races, ethnic groups and cultures. In the United States a CDC survey based on data from 2013 to 2015 showed 54.4 million (22.7%) adults had self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis, and 23.7 million (43.5% of those with arthritis) had arthritis-attributable activity limitation (AAAL). With an aging population, this number is expected to increase. Adults with co-morbid conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes, and obesity, were seen to have a higher than average prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis (49.3%, 47.1%, and 30.6% respectively).[100]

Disability due to musculoskeletal disorders increased by 45% from 1990 to 2010. Of these, osteoarthritis is the fastest increasing major health condition.[101] Among the many reports on the increased prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions, data from Africa are lacking and underestimated. A systematic review assessed the prevalence of arthritis in Africa and included twenty population-based and seven hospital-based studies.[102] The majority of studies, twelve, were from South Africa. Nine studies were well-conducted, eleven studies were of moderate quality, and seven studies were conducted poorly. The results of the systematic review were as follows:

- Rheumatoid arthritis: 0.1% in Algeria (urban setting); 0.6% in Democratic Republic of Congo (urban setting); 2.5% and 0.07% in urban and rural settings in South Africa respectively; 0.3% in Egypt (rural setting), 0.4% in Lesotho (rural setting)

- Osteoarthritis: 55.1% in South Africa (urban setting); ranged from 29.5 to 82.7% in South Africans aged 65 years and older

- Knee osteoarthritis has the highest prevalence from all types of osteoarthritis, with 33.1% in rural South Africa

- Ankylosing spondylitis: 0.1% in South Africa (rural setting)

- Psoriatic arthritis: 4.4% in South Africa (urban setting)

- Gout: 0.7% in South Africa (urban setting)

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: 0.3% in Egypt (urban setting)

History

Evidence of osteoarthritis and potentially inflammatory arthritis has been discovered in dinosaurs.[103][104] The first known traces of human arthritis date back as far as 4500 BC. In early reports, arthritis was frequently referred to as the most common ailment of prehistoric peoples.[105] It was noted in skeletal remains of Native Americans found in Tennessee and parts of what is now Olathe, Kansas. Evidence of arthritis has been found throughout history, from Ötzi, a mummy (c. 3000 BC) found along the border of modern Italy and Austria, to the Egyptian mummies circa 2590 BC.[106]

In 1715, William Musgrave published the second edition of his most important medical work, De arthritide symptomatica, which concerned arthritis and its effects.[107] Augustin Jacob Landré-Beauvais, a 28-year-old resident physician at Saltpêtrière Asylum in France was the first person to describe the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. Though Landré-Beauvais' classification of rheumatoid arthritis as a relative of gout was inaccurate, his dissertation encouraged others to further study the disease.[108]

Terminology

The term is derived from arthr- (from Ancient Greek: ἄρθρον, romanized: árthron, lit. 'joint') and -itis (from -ῖτις, -îtis, lit. 'pertaining to'), the latter suffix having come to be associated with inflammation.

The word arthritides is the plural form of arthritis, and denotes the collective group of arthritis-like conditions.[109]

See also

- Antiarthritics

- Arthritis Care (charity in the UK)

- Arthritis Foundation (US not-for-profit)

- Knee arthritis

- Osteoimmunology

- Weather pains

References

- "arthritis noun - Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary". www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- "Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases". NIAMS. October 2014. Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- "Arthritis Types". CDC. June 22, 2016. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Athanasiou, Kyriacos A.; Darling, Eric M.; Hu, Jerry C.; DuRaine, Grayson D.; Reddi, A. Hari (2013). Articular Cartilage. CRC Press. p. 105. ISBN 9781439853252. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- "Arthritis Basics". CDC. May 9, 2016. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "Living With Arthritis: Health Information Basics for You and Your Family". NIAMS. July 2014. Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "Arthritis". mayoclinic.org. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

{{cite web}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help) - "Arthritis: An Overview". OrthoInfo. October 2007. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Berkowitz., Clegg, Holly (2013). Eating well to fight arthritis: 200 easy recipes and practical tips to help reduce inflammation and ease symptoms. ISBN 978-0-9815640-5-0. OCLC 854909375.

- "Traditional Chinese Medicine Formula in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis of Knees or Hips". Case Medical Research. 2019-10-01. doi:10.31525/ct1-nct04110847. ISSN 2643-4652. S2CID 242704843.

- "Arthritis". CDC. July 22, 2015. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- SIDE EFFECTS MAY INCLUDE STRANGERS, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2020-10-22, p. 27, doi:10.2307/j.ctv1ghv4jh.24, S2CID 243669150, retrieved 2022-04-23

- "Blood-pressure pill may also aid weight loss". New Scientist. 198 (2654): 16. May 2008. doi:10.1016/s0262-4079(08)61076-3. ISSN 0262-4079.

- "Higher-than-recommended doses of antipsychotic medications may not benefit people with schizophrenia and may increase side effects". PsycEXTRA Dataset. 2007. doi:10.1037/e603782007-025. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- March L, Smith EU, Hoy DG, Cross MJ, Sanchez-Riera L, Blyth F, Buchbinder R, Vos T, Woolf AD (June 2014). "Burden of disability due to musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 28 (3): 353–66. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2014.08.002. PMID 25481420.

- Richette P, Bardin T (January 2010). "Gout". Lancet. 375 (9711): 318–28. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60883-7. PMID 19692116. S2CID 208793280.

- "National Health Survey". ABS. 8 December 2015. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- Pirotta M (September 2010). "Arthritis disease - the use of complementary therapies". Australian Family Physician. 39 (9): 638–40. PMID 20877766.

- Waite, Maurice, ed. (2012). Paperback Oxford English Dictionary. OUP Oxford. p. 35. ISBN 9780199640942. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- Leonard PC (2015). Quick & Easy Medical Terminology - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 160. ISBN 9780323370646.

- "Osteoarthritis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "Rheumatoid Arthritis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "Gout". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "Septic Arthritis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "Ankylosing Spondylitis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- Prakken, B; Albani, S; Martini, A (18 June 2011). "Juvenile idiopathic arthritis". Lancet. 377 (9783): 2138–49. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60244-4. PMID 21684384. S2CID 202802455.

- Akkara Veetil BM, Yee AH, Warrington KJ, Aksamit AJ Jr, Mason TG (December 2012). "Aseptic meningitis in adult onset Still's disease". Rheumatol Int. 32 (12): 4031–4. doi:10.1007/s00296-010-1529-8. PMID 20495923. S2CID 19431424.

- Nancy Garrick, Deputy Director (2017-04-14). "Psoriatic Arthritis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

- "Questions and Answers About Psoriasis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 2017-04-12. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- American College of Rheumatology. "Reactive Arthritis". Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- "Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- McDowell, Lisa A.; Kudaravalli, Pujitha; Sticco, Kristin L. (2021), "Iron Overload", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30252387, retrieved 2021-11-24

- "Hepatitis". MedlinePlus. 2020-05-20. Retrieved 2020-07-19.

Your liver is the largest organ inside your body. It helps your body digest food, store energy, and remove poisons. Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver.

- "Hepatitis". NIAID. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- "Lyme Disease". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "What Is Sjögren's Syndrome? Fast Facts". NIAMS. November 2014. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "Hashimoto's Thyroiditis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- Guandalini S, Assiri A (Mar 2014). "Celiac disease: a review". JAMA Pediatr. 168 (3): 272–8. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3858. PMID 24395055.

- Fasano A, Sapone A, Zevallos V, Schuppan D (May 2015). "Nonceliac gluten sensitivity". Gastroenterology. 148 (6): 1195–204. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.049. PMID 25583468.

- Volta U, Caio G, De Giorgio R, Henriksen C, Skodje G, Lundin KE (Jun 2015). "Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: a work-in-progress entity in the spectrum of wheat-related disorders". Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 29 (3): 477–91. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2015.04.006. PMID 26060112.

- Catassi C, Bai J, Bonaz B, Bouma G, Calabrò A, Carroccio A, Castillejo G, Ciacci C, Cristofori F, Dolinsek J, Francavilla R, Elli L, Green P, Holtmeier W, Koehler P, Koletzko S, Meinhold C, Sanders D, Schumann M, Schuppan D, Ullrich R, Vécsei A, Volta U, Zevallos V, Sapone A, Fasano A (2013). "Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders". Nutrients (Review). 5 (10): 3839–3853. doi:10.3390/nu5103839. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 3820047. PMID 24077239.

- "Crohn's Disease". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 28 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "Ulcerative Colitis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 26 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "Henoch-Schönlein Purpura". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "Sarcoidosis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "Whipple's Disease". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- Rezaei, Nima (November 2006). "TNF-receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS): an autosomal dominant multisystem disorder". Clinical Rheumatology. 25 (6): 773–777. doi:10.1007/s10067-005-0198-6. PMID 16447098. S2CID 41808394.subscription needed

- James W, Berger T, Elston D (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- "Systemic Lupus Erythematosus". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- Wollenhaupt J, Zeidler H (1998). "Undifferentiated arthritis and reactive arthritis". Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 10 (4): 306–313. doi:10.1097/00002281-199807000-00005. PMID 9725091.

- Swash, Michael; Glynn, Michael, eds. (2007). Hutchison's Clinical Methods: An Integrated Approach to Clinical Practice (22nd ed.). Edinburgh: Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0702027994.

- Eustice, Carol (2012). Arthritis: types of arthritis. Adams Media. ISBN 978-1-4405-4446-0. OCLC 808835849.

- Galloway, James B.; Scott, David L. (December 2017), "Management of common types of arthritis in older adults", Oxford Textbook of Geriatric Medicine, Oxford University Press, pp. 577–584, doi:10.1093/med/9780198701590.003.0075, ISBN 978-0-19-870159-0, retrieved 2022-04-23

- "Direct and Indirect Costs of Musculoskeletal Conditions in 1997: Total and Incremental Estimates Revised Final Report (July, 2003)". Amazon. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "Rheumatoid Arthritis and Heart Disease Risk: Atherosclerosis, Heart Attacks, and More". Archived from the original on 2015-03-27. Retrieved 2015-06-09.

- "Coping With Depression and Rheumatoid Arthritis". Archived from the original on 2015-05-14. Retrieved 2015-06-09.

- "Arthritis Risk Factors". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- "Smoking and Rheumatoid Arthritis". NRAS. National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- "How is arthritis diagnosed? | Arthritis Research UK". www.arthritisresearchuk.org. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-06-09.

- Nancy Garrick, Deputy Director (2017-04-20). "Rheumatoid Arthritis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- VanItallie TB (October 2010). "Gout: epitome of painful arthritis". Metab. Clin. Exp. 59 (Suppl 1): S32–6. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2010.07.009. PMID 20837191.

- "Osteoarthritis in Dogs | American College of Veterinary Surgeons - ACVS". www.acvs.org. Retrieved 2021-04-06.

- Pereira, Duarte; Ramos, Elisabete; Branco, Jaime (January 2015). "Osteoarthritis". Acta Médica Portuguesa. 28 (1): 99–106. doi:10.20344/amp.5477. ISSN 1646-0758. PMID 25817486.

- Zhang Y, Jordan J (2010). "Epidemiology of Osteoarthritis". Clin Geriatr Med. 26 (3): 355–69. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.001. PMC 2920533. PMID 20699159.

- Ideguchi H, Ohno S, Hattori H, Senuma A, Ishigatsubo Y (2006). "Bone erosions in rheumatoid arthritis can be repaired through reduction in disease activity with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 8 (3): R76. doi:10.1186/ar1943. PMC 1526642. PMID 16646983.

- "Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | Arthritis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-03-05. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Arthritis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-02-21. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- staff, familydoctor org editorial. "What Is Rheumatoid Arthritis? Symptoms And Treatment". familydoctor.org. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Deane, Kevin D.; Demoruelle, M. Kristen; Kelmenson, Lindsay B.; Kuhn, Kristine A.; Norris, Jill M.; Holers, V. Michael (February 2017). "Genetic and environmental risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis". Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 31 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2017.08.003. PMC 5726551. PMID 29221595.

- "Arthritis - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic.

- Chabaud M, Garnero P, Dayer JM, Guerne PA, Fossiez F, Miossec P (2000). "Contribution of interleukin 17 to synovium matrix destruction in rheumatoid arthritis". Cytokine. 12 (7): 1092–9. doi:10.1006/cyto.2000.0681. PMID 10880256.

- Won HY, Lee JA, Park ZS, Song JS, Kim HY, Jang SM, Yoo SE, Rhee Y, Hwang ES, Bae MA (2011). "Prominent bone loss mediated by RANKL and IL-17 produced by CD4+ T cells in TallyHo/JngJ mice". PLOS ONE. 6 (3): e18168. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618168W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018168. PMC 3064589. PMID 21464945.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis: Differential Diagnoses & Workup~diagnosis at eMedicine

- Becker, Michael A. (2005). Arthritis and Allied Conditions: A textbook of Rheumatology edition 15. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 2303–2339.

- Ali S, Lally EV (November 2009). "Treatment failure gout". Medicine and Health, Rhode Island. 92 (11): 369–71. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.608.3812. PMID 19999896.

- Unless otherwise specified in table box, the reference is: Agabegi, Elizabeth D.; Agabegi, Steven S. (2008). "Table 6–7". Step-Up to Medicine. Step-Up Series. Hagerstwon MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-7817-7153-5.

- Diagnosis lag time of median 4 weeks, and median diagnosis lag time of 18 weeks, taken from: Chan KW, Felson DT, Yood RA, Walker AM (1994). "The lag time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 37 (6): 814–820. doi:10.1002/art.1780370606. PMID 8003053.

- Schaider, Jeffrey; Wolfson, Allan B.; Gregory W Hendey; Louis Ling; Carlo L Rosen (2009). Harwood-Nuss' Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine (Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine (Harwood-Nuss)). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 740 (upper right of page). ISBN 978-0-7817-8943-1. Archived from the original on 2015-03-21.

- Severe Arthritis Disease Facts Archived 2007-04-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2010-02-05

- Psoriatic Arthritis Archived 2010-02-09 at the Wayback Machine Mayo Clinic. Retrieved on 2010-02-05

- "Knee braces for osteoarthritis - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2021-03-31.

- Ettinger WH, Burns R, Messier SP, Applegate W, Rejeski WJ, Morgan T, Shumaker S, Berry MJ, O'Toole M, Monu J, Craven T (1997). "A randomized trial comparing aerobic exercise and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. The Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST)". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 277 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540250033028. PMID 8980206.

- Fransen M, Crosbie J, Edmonds J (January 2001). "Physical therapy is effective for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled clinical trial (2001)". J. Rheumatol. 28 (1): 156–64. PMID 11196518.

- "The Role of Occupational Therapy in Providing Assistive Technology Devices and Services". www.aota.org. 2018. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- "Arthritis Drugs". arthritistoday.org. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved July 5, 2010.

- Reid MC, Shengelia R, Parker SJ (Mar 2012). "Pharmacologic management of osteoarthritis-related pain in older adults". The American Journal of Nursing. 112 (3 Suppl 1): S38–43. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000412650.02926.e3. PMC 3733545. PMID 22373746.

- Taruc-Uy, Rafaelani L.; Lynch, Scott A. (December 2013). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteoarthritis". Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 40 (4): 821–836. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.08.003. PMID 24209720.

- Kurebayashi Y, Nagai S, Ikejiri A, Koyasu S (2013). "Recent advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms of the development and function of Th17 cells". Genes Cells. 18 (4): 247–65. doi:10.1111/gtc.12039. PMC 3657121. PMID 23383714.

- Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, Giffin JR, Willits KR, Wong CJ, Feagan BG, Donner A, Griffin SH, D'Ascanio LM, Pope JE, Fowler PJ (2008). "A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee". N. Engl. J. Med. 359 (11): 1097–107. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708333. PMID 18784099.

- "10 Terrific Arthritis Gadgets - Arthritis Center - Everyday Health". EverydayHealth.com. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- "3-D Printing Offers Helping Hand to People with Arthritis". OrthoFeed. 2018-12-15. Archived from the original on 2020-11-15. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- Gallup N, Bow JK, Pearce JM (December 2018). "Economic Potential for Distributed Manufacturing of Adaptive Aids for Arthritis Patients in the U.S". Geriatrics. 3 (4): 89. doi:10.3390/geriatrics3040089. PMC 6371113. PMID 31011124.

- Yeung KT, Lin CH, Teng YL, Chen FF, Lou SZ, Chen CL (2016-03-29). "Use of and Self-Perceived Need for Assistive Devices in Individuals with Disabilities in Taiwan". PLOS ONE. 11 (3): e0152707. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1152707Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152707. PMC 4811424. PMID 27023276.

- Rutjes AW, Nüesch E, Sterchi R, Kalichman L, Hendriks E, Osiri M, Brosseau L, Reichenbach S, Jüni P (October 2009). "Transcutaneous electrostimulation for osteoarthritis of the knee" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD002823. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002823.pub2. PMC 7120411. PMID 19821296.

- Brosseau L, Welch V, Wells G, Tugwell P, de Bie R, Gam A, Harman K, Shea B, Morin M (August 2000). "Low level laser therapy for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a metaanalysis". The Journal of Rheumatology. 27 (8): 1961–9. PMID 10955339.

- Brosseau L, Robinson V, Wells G, Debie R, Gam A, Harman K, Morin M, Shea B, Tugwell P (October 2005). "Low level laser therapy (Classes I, II and III) for treating rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (4): CD002049. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002049.pub2. PMC 8406947. PMID 16235295.

- Vavken P, Arrich F, Schuhfried O, Dorotka R (May 2009). "Effectiveness of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy in the management of osteoarthritis of the knee: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 41 (6): 406–11. doi:10.2340/16501977-0374. PMID 19479151.

- Canada, Health (2002-07-16). "Medical Devices Active Licence Listing (MDALL)". aem. Retrieved 2020-03-28.

- "Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Barbour, Kamil E.; Helmick, Charles G.; Boring, Michael; Brady, Teresa J. (2017-03-10). "Vital Signs: Prevalence of Doctor-Diagnosed Arthritis and Arthritis-Attributable Activity Limitation — United States, 2013–2015". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 66 (9): 246–253. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6609e1. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 5687192. PMID 28278145.

- GBD 2010 Country Collaboration (March 2013). "GBD 2010 country results: a global public good". Lancet. 381 (9871): 965–70. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60283-4. PMID 23668561. S2CID 11808683.

- Usenbo A, Kramer V, Young T, Musekiwa A (4 August 2015). "Prevalence of Arthritis in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0133858. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1033858U. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133858. PMC 4524637. PMID 26241756.

- Joel A. DeLisa; Bruce M. Gans; Nicholas E. Walsh (2005). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 765–. ISBN 978-0-7817-4130-9. Archived from the original on 2017-01-08.

- Blumberg BS, Sokoloff L (1961). "Coalescence of caudal vertebrae in the giant dinosaur Diplodocus". Arthritis Rheum. 4 (6): 592–601. doi:10.1002/art.1780040605. PMID 13870231.

- Bridges PS (1992). "Prehistoric Arthritis in the Americas". Annual Review of Anthropology. 21: 67–91. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.21.100192.000435.

- Arthritis History Archived 2010-01-30 at the Wayback Machine Medical News

- Alick Cameron, "Musgrave, William (1655–1721)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004

- Entezami P, Fox DA, Clapham PJ, Chung KC (February 2011). "Historical perspective on the etiology of rheumatoid arthritis". Hand Clinics. 27 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2010.09.006. PMC 3119866. PMID 21176794.

- "Definition of ARTHRITIDES". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

External links

- Arthritis at Curlie

- American College of Rheumatology – US professional society of rheumatologists

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases - US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases