Ductus venosus

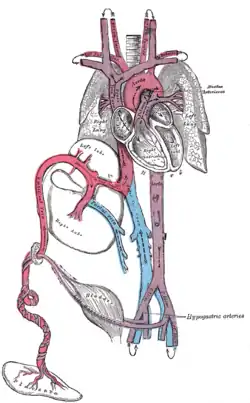

In the fetus, the ductus venosus (Arantius' duct after Julius Caesar Aranzi[1]) shunts a portion of umbilical vein blood flow directly to the inferior vena cava.[2] Thus, it allows oxygenated blood from the placenta to bypass the liver. Compared to the 50% shunting of umbilical blood through the ductus venosus found in animal experiments, the degree of shunting in the human fetus under physiological conditions is considerably less, 30% at 20 weeks, which decreases to 18% at 32 weeks, suggesting a higher priority of the fetal liver than previously realized.[3] In conjunction with the other fetal shunts, the foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus, it plays a critical role in preferentially shunting oxygenated blood to the fetal brain. It is a part of fetal circulation.

| Ductus venosus | |

|---|---|

| |

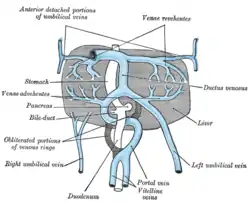

The liver and the veins in connection with it, of a human embryo, twenty-four or twenty-five days old, as seen from the ventral surface. | |

| Details | |

| Source | Umbilical vein |

| Drains to | Inferior vena cava |

| Artery | Ductus arteriosus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Ductus venosus |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Anatomic course

The pathway of fetal umbilical venous flow is umbilical vein to left portal vein to ductus venosus to inferior vena cava and eventually the right atrium. This anatomic course is important in the assessment of neonatal umbilical venous catheterization, as failure to cannulate through the ductus venosus results in malpositioned hepatic catheterization via the left or right portal veins. Complications of such positioning can include hepatic hematoma or abscess.

Postnatal closure

The ductus venosus is open at the time of birth and that is the reason why umbilical vein catheterization works. The ductus venosus naturally closes during the first week of life in most full-term neonates; however, it may take much longer to close in pre-term neonates. Functional closure occurs within minutes of birth. Structural closure in term babies occurs within 3 to 7 days.

After it closes, the remnant is known as ligamentum venosum.

If the ductus venosus fails to occlude after birth, it remains patent (open), and the individual is said to have a patent ductus venosus and thus an intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (PSS).[4] This condition is hereditary in some dog breeds (e.g. Irish Wolfhound). The ductus venosus shows a delayed closure in preterm infants, with no significant correlation to the closure of the ductus arteriosus or the condition of the infant.[5] Possibly, increased levels of dilating prostaglandins leads to a delayed occlusion of the vessel.[5]

References

- "Whonamedit - dictionary of medical eponyms". www.whonamedit.com.

- Kiserud, T.; Rasmussen, S.; Skulstad, S. (2000). "Blood flow and the degree of shunting through the ductus venosus in the human fetus". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 182 (1 Pt 1): 147–153. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(00)70504-7. PMID 10649170.

- Kiserud, T (2000). "Fetal venous circulation -- an update on hemodynamics". J Perinat Med. 28 (2): 90–6. doi:10.1515/JPM.2000.011. PMID 10875092. S2CID 11799576.

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, Patent ductus venosus; PDV.

- Fugelseth D, Lindemann R, Liestøl K, Kiserud T, Langslet A (December 1998). "Postnatal closure of ductus venosus in preterm infants ≤32 weeks. An ultrasonographic study". Early Hum. Dev. 53 (2): 163–9. doi:10.1016/s0378-3782(98)00051-6. PMID 10195709.