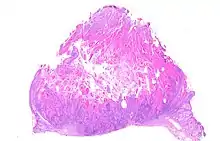

Keratoacanthoma

Keratoacanthoma (KA) is a common low-grade (unlikely to metastasize or invade) rapidly-growing skin tumour that is believed to originate from the hair follicle (pilosebaceous unit) and can resemble squamous cell carcinoma.[1][2]

| Keratoacanthoma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Keratoacanthoma | |

| Specialty | Dermatology, plastic surgery |

| Types |

|

| Risk factors | Ultraviolet radiation, immunosuppression, genetics |

| Diagnostic method | Tissue biopsy |

| Differential diagnosis | Squamous cell skin cancer |

| Treatment | Surgery (excision, Mohs surgery) |

The defining characteristic of a keratoacanthoma is that it is dome-shaped, symmetrical, surrounded by a smooth wall of inflamed skin, and capped with keratin scales and debris. It grows rapidly, reaching a large size within days or weeks, and if untreated for months will almost always starve itself of nourishment, necrose (die), slough, and heal with scarring. Keratoacanthoma is commonly found on sun-exposed skin, often face, forearms and hands.[2][3] It is rarely found at a mucocutaneous junction or on mucous membranes.[2]

Keratoacanthoma may be difficult to distinguish visually from a skin cancer.[4] Under the microscope, keratoacanthoma very closely resembles squamous cell carcinoma. In order to differentiate between the two, almost the entire structure needs to be removed and examined. While some pathologists classify keratoacanthoma as a distinct entity and not a malignancy, about 6% of clinical and histological keratoacanthomas do progress to invasive and aggressive squamous cell cancers; some pathologists may label KA as "well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma variant", and prompt definitive surgery may be recommended.[5][6][7][8]

Classification

Frequently reported and reclassified over the last century, keratoacanthoma can be divided into various subtypes and despite being considered benign, their unpredictable behaviour has warranted the same attention as with squamous cell carcinoma.[1]

Keratoacanthomas may be divided into the following types:[9]: 763–764 [10]: 643–646

- Giant keratoacanthomas are a variant of keratoacanthoma, which may reach dimensions of several centimeters.[9]: 763

- Keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum is a cutaneous condition, a variant of keratoacanthomas, which is characterized by multiple tumors growing in a localized area.[9]: 763 [10]: 645

- Multiple keratoacanthomas (also known as "Ferguson–Smith syndrome," "Ferguson-Smith type of multiple self-healing keratoacanthomas,") is a cutaneous condition, a variant of keratoacanthomas, which is characterized by the appearance of multiple, sometimes hundreds of keratoacanthomas.[9]: 763 [10]: 644

- A solitary keratoacanthoma (also known as "Subungual keratoacanthoma") is a benign, but rapidly growing, locally aggressive tumor which sometimes occur in the nail apparatus.[9]: 667, 764 [10]: 644

- Generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma (also known as "Generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski") is a cutaneous condition, a variant of keratoacanthomas, characterized by hundreds to thousands of tiny follicular keratotic papules over the entire body.[9]: 763 [10] : 645 Treatments are not successful for many people with generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma. Use of emollients and anti-itch medications can ease some symptoms. Improvement or complete resolutions of the condition has occurred with the application of the following medications: acitretin, isotretinoin, fluorouracil, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide.[11]

Cause

Keratoacanthomas usually occurs in older individuals. A number of causes have been suggested including ultraviolet light, chemical carcinogens, recent injury to the skin, immunosuppression and genetic predisposition.[1] As with squamous cell cancer, sporadic cases have been found co-infected with the human papilloma virus (HPV).[4][12] Although HPV has been suggested as a causal factor, it is unproven.[2]

Many new treatments for melanoma are also known to increase the rate of keratoacanthoma, such as the BRAF inhibitor medications vemurafenib and dabrafenib.[13]

Diagnosis

Keratoacanthomas presents as a fleshy, elevated and nodular lesion with an irregular crater shape and a characteristic central hyperkeratotic core. Usually the people will notice a rapidly growing dome-shaped tumor on sun-exposed skin.[14]

If the entire lesion is removed, the pathologist will probably be able to differentiate between keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Follow-up would be required to monitor for recurrence of disease.[15]

Treatment

Excision of the entire lesion, with adequate margin, will remove the lesion, allow full tissue diagnosis, and leave a planned surgical wound which can usually be repaired with a good cosmetic result. However, removing the entire lesion (especially on the face) may present difficult problems of plastic reconstruction. (On the nose and face, Mohs surgery may allow for good margin control with minimal tissue removal, but many insurance companies require the definitive diagnosis of a malignancy before they are prepared to pay the extra costs of Mohs surgery.) Especially in more cosmetically-sensitive areas, and where the clinical diagnosis is reasonably certain, alternatives to surgery may include no treatment (awaiting spontaneous resolution).[14]

On the trunk, arms, and legs, electrodesiccation and curettage often suffice to control keratoacanthomas until they regress. Other modalities of treatment include cryosurgery and radiotherapy; intralesional injection of methotrexate or 5-fluorouracil have also been used.[14]

Recurrence after electrodesiccation and curettage can occur; it can usually be identified and treated promptly with either further curettage or surgical excision.[6]

History

In 1889, Sir Jonathan Hutchinson described a crateriform ulcer on the face”.[16] In 1936, the same condition was renamed "molluscum sebaceum" by MacCormac and Scarf.[17] Later, the term “keratoacanthoma” was coined by Walter Freudenthal[18][19] and the term became established by Arthur Rook and pathologist Ian Whimster in 1950.[16]

See also

- List of cutaneous conditions

- Marian Grzybowski

References

- Zito, Patrick M.; Scharf, Richard (2018), "Keratoacanthoma", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29763106, retrieved 17 September 2018

- Joseph A. Regezi; James Sciubba; Richard C. K. Jordan (2012). "6. Neoplasms". Oral Pathology - E-Book: Clinical Pathologic Correlations. Elsevier Saunders. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-4557-0262-6.

- Schwartz RA. The Keratoacanthoma: A Review. J Surg Oncol 1979; 12:305–17.

- "Keratoacanthoma | DermNet New Zealand". www.dermnetnz.org. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- Ko CJ, Keratoacanthoma: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010; 28(3):254–61 (ISSN 1879-1131)

- "Keratoacanthoma: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". Medscape. 14 August 2018.(subscription required)

- Kossard S; Tan KB; Choy C; Keratoacanthoma and infundibulocystic squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008; 30(2):127–34 (ISSN 1533-0311)

- Weedon DD, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in keratoacanthoma: a neglected phenomenon in the elderly. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010; 32(5):423–6

- Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- "Grzybowski generalized eruptive keratoacanthomas | DermNet New Zealand". www.dermnetnz.org. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- Niebuhr M, et al. Giant keratoacanthoma in an immunocompetent patient with detection of HPV 11. Hautarzt. 2009; 60(3):229–32 (ISSN 1432-1173)

- Niezgoda, A (2015). "Novel Approaches to Treatment of Advanced Melanoma: A Review on Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy". Biomed Res Int. 2015: 851387. doi:10.1155/2015/851387. PMC 4478296. PMID 26171394.

- Keratoacanthoma. Désirée Ratner. 2004. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/467069 accessed 23 June 2015

- Baran, Robert; Berker, David A. R. de; Holzberg, Mark; Thomas, Luc (2012). Baran and Dawber's Diseases of the Nails and their Management. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470657355.

- Cerroni, Lorenzo; Kerl, Helmut (2012), Goldsmith, Lowell A.; Katz, Stephen I.; Gilchrest, Barbara A.; Paller, Amy S. (eds.), "Chapter 117. Keratoacanthoma", Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine (8 ed.), The McGraw-Hill Companies, retrieved 2018-08-20

- Levy, Edwin J. (1954-06-05). "Keratoacanthoma". Journal of the American Medical Association. 155 (6): 562–4. doi:10.1001/jama.1954.03690240028008. ISSN 0002-9955. PMID 13162754.

- HJORTH, NIELS (August 1960). "Keratoacanthoma: A Historical Note". British Journal of Dermatology. 72 (8–9): 292–295. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1960.tb13896.x. ISSN 0007-0963. S2CID 71452344.

- ROOK, ARTHUR; WHIMSTER, IAN (January 1979). "Keratoacanthoma–a thirty year retrospect". British Journal of Dermatology. 100 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979.tb03568.x. ISSN 0007-0963. PMID 427012. S2CID 27373097.