Basal-cell carcinoma

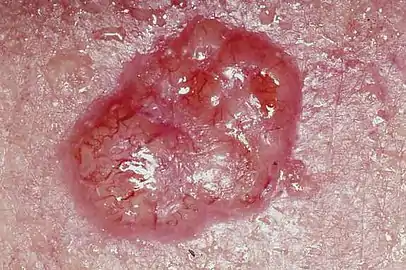

Basal-cell carcinoma (BCC), also known as basal-cell cancer, is the most common type of skin cancer.[2] It often appears as a painless raised area of skin, which may be shiny with small blood vessels running over it.[1] It may also present as a raised area with ulceration.[1] Basal-cell cancer grows slowly and can damage the tissue around it, but it is unlikely to spread to distant areas or result in death.[7]

| Basal-cell carcinoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Basal-cell skin cancer, basalioma |

| |

| An ulcerated basal cell carcinoma near the ear of a 75-year-old male | |

| Specialty | Dermatology, oncology |

| Symptoms | Painless raised area of skin that may be shiny with small blood vessel running over it or ulceration[1] |

| Risk factors | Light skin, ultraviolet light, radiation therapy, arsenic, poor immune function[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Examination, skin biopsy[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Milia, seborrheic keratosis, melanoma, psoriasis[4] |

| Treatment | Surgical removal[2] |

| Prognosis | Good[5] |

| Frequency | ~30% of white people at some point (US)[2] |

| Deaths | Rare[6] |

Risk factors include exposure to ultraviolet light, having lighter skin, radiation therapy, long-term exposure to arsenic and poor immune-system function.[2] Exposure to UV light during childhood is particularly harmful.[5] Tanning beds have become another common source of ultraviolet radiation.[8] Diagnosis often depends on skin examination, confirmed by tissue biopsy.[2][3]

It remains unclear whether sunscreen affects the risk of basal-cell cancer.[9] Treatment is typically by surgical removal.[2] This can be by simple excision if the cancer is small; otherwise, Mohs surgery is generally recommended.[2] Other options include electrodesiccation and curettage, cryosurgery, topical chemotherapy, photodynamic therapy, laser surgery or the use of imiquimod, a topical immune-activating medication.[10] In the rare cases in which distant spread has occurred, chemotherapy or targeted therapy may be used.[10]

Basal-cell cancer accounts for at least 32% of all cancers globally.[7][11] Of skin cancers other than melanoma, about 80% are basal-cell cancers.[2] In the United States, about 35% of white males and 25% of white females are affected by BCC at some point in their lives.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Individuals with a basal-cell carcinoma typically present with a shiny, pearly skin nodule. However, superficial basal-cell cancer can present as a red patch similar to eczema. Infiltrative or morpheaform basal-cell cancers can present as a skin thickening or scar tissue – making diagnosis difficult without using tactile sensation and a skin biopsy. It is often difficult to visually distinguish basal-cell cancer from acne scar, actinic elastosis, and recent cryodestruction inflammation.

Basal cell carcinoma on patient's back

Basal cell carcinoma on patient's back Basal-cell carcinoma

Basal-cell carcinoma Basal cell carcinoma on the left upper back, nodular and micronodular, marked for biopsy

Basal cell carcinoma on the left upper back, nodular and micronodular, marked for biopsy Dermoscopy showing telangiectatic vessels

Dermoscopy showing telangiectatic vessels

Cause

The majority of basal-cell carcinomas occur on sun-exposed areas of the body.[12]

Pathophysiology

Basal-cell carcinoma is named after the basal cells that populate the lowest layer of the epidermis due to the histological appearance of the cancer cells under the microscope.[13] Nevertheless, not all basal-cell carcinomas actually originate within the basal layer.[13] Basal-cell carcinomas are thought to develop from the folliculo–sebaceous–apocrine germinative cells known as trichoblasts. Trichoblastic carcinoma is a term used to describe a rare and potentially aggressive malignancy that is also thought to arise from trichoblasts and may resemble a benign trichoblastoma (differential diagnosis can be challenging).[14][15][16] It has been suggested that lesions diagnosed as 'trichoblastic carcinoma' may actually themselves be basal-cell carcinoma.[17]

Overexposure to sun leads to the formation of thymine dimers, a form of DNA damage. While DNA repair removes most UV-induced damage, not all crosslinks are excised. There is, therefore, cumulative DNA damage leading to mutations. Apart from the mutagenesis, overexposure to sunlight depresses the local immune system, possibly decreasing immune surveillance for new tumor cells.

Basal-cell carcinomas can often come in association with other lesions of the skin, such as actinic keratosis, seborrheic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma.[18] In a small proportion of cases, basal-cell carcinoma also develops as a result of basal-cell nevus syndrome, or Gorlin Syndrome, which is also characterized by keratocystic odontogenic tumors of the jaw, palmar or plantar (sole of the foot) pits, calcification of the falx cerebri (in the center line of the brain) and rib abnormalities. The cause of this syndrome is a mutation in the PTCH1 tumor suppressor gene located in chromosome 9q22.3, which inhibits the hedgehog signaling pathway. A mutation in the SMO gene, which is also on the hedgehog pathway, also causes basal-cell carcinoma.[19]

Diagnosis

To diagnose basal-cell carcinomas, a skin biopsy is performed for histopathologic analyses. The most common method is a shave biopsy under local anesthesia. Most nodular basal-cell cancers can be diagnosed clinically; however, other variants can be very difficult to distinguish from benign lesions such as intradermal naevus, sebaceomas, fibrous papules, early acne scars, and hypertrophic scarring.[20] Exfoliative cytology methods have high sensitivity and specificity for confirming the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma when clinical suspicion is high but unclear usefulness otherwise.[21]

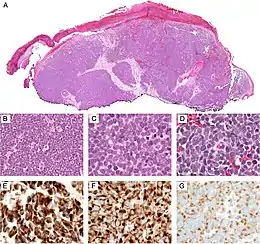

Characteristics

Basal-cell carcinoma cells appear similar to epidermal basal cells, and are usually well differentiated.[22]

In uncertain cases, immunohistochemistry using BerEP4 can be used, having a high sensitivity and specificity in detecting only BCC cells.[23]

Main classes

Basal-cell carcinoma can broadly be divided into three groups, based on the growth patterns.

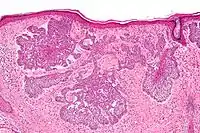

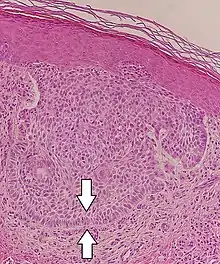

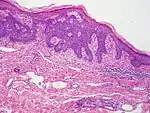

- Superficial basal-cell carcinoma, formerly referred to in-situ basal-cell carcinoma, is characterized by a superficial proliferation of neoplastic basal-cells. This tumor is generally responsive to topic chemotherapy, such as imiquimod, or fluorouracil, although surgical treatment is better able to ensure complete removal and confirm that there is not an underlying more aggressive subtype that was not sampled in the initial biopsy.

- Infiltrative basal-cell carcinoma, which also encompasses morpheaform and micronodular basal-cell cancer, is more difficult to treat with conservative methods, given its tendency to penetrate into deeper layers of the skin.

- Nodular basal-cell carcinoma includes most of the remaining categories of basal-cell cancer. It is not unusual to encounter heterogeneous morphologic features within the same tumor.

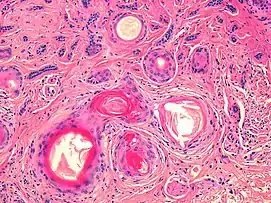

Nodular basal-cell carcinoma

.jpg.webp)

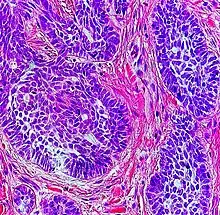

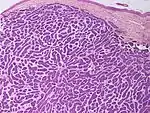

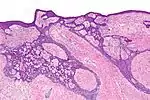

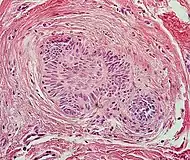

Nodular basal-cell carcinoma (also known as "classic basal-cell carcinoma") accounts for 50% of all BCC.[24] It most commonly occurs on the sun-exposed areas of the head and neck.[25]: 748 [26]: 646 Histopathology shows aggregates of basaloid cells with well-defined borders, showing a peripheral palisading of cells and one or more typical clefts.[24] Such clefts are caused by shrinkage of mucin during tissue fixation and staining.[27] Central necrosis with eosinophilic, granular features may be also present, as well as mucin. The heavy aggregates of mucin determine a cystic structure. Calcification may be also present, especially in long-standing lesions.[24] Mitotic activity is usually not so evident, but a high mitotic rate may be present in more aggressive lesions.[24] Adenoidal BCC can be classified as a variant of NBCC, characterized by basaloid cells with a reticulated configuration extending into the dermis.[24]

Cleft.

Cleft.

Other subtypes

Other more specific subtypes of basal-cell carcinoma include:[25][26]: 646–50

| Type | Histopathology | Other characteristics | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

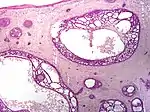

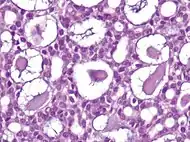

| Cystic basal-cell carcinoma | Morphologically characterized by dome-shaped, blue-gray cystic nodules.[26]: 647 |  | |

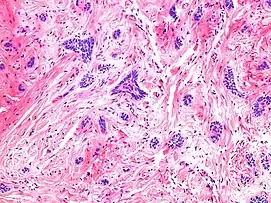

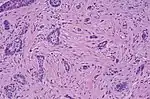

| Morpheaform basal-cell carcinoma (also known as "cicatricial basal-cell carcinoma", and "morphoeic basal-cell carcinoma") | Narrow strands and nests of basaloid cells, surrounded by dense sclerotic stroma.[28] | Aggressive[25]: 748 [26]: 647 |  |

| Infiltrative basal-cell carcinoma | Deep infiltration.[26]: 647 | Aggressive[26]: 647 | |

| Micronodular basal-cell carcinoma | Small and closely spaced nests. |  | |

| Superficial basal-cell carcinoma (also known as "superficial multicentric basal-cell carcinoma") | Occurs most commonly on the trunk and appears as an erythematous patch.[25]: 748 [26]: 647 |  | |

| Pigmented basal-cell carcinoma exhibits increased melanization.[25]: 748 [26]: 647 | About 80% of all basal-cell carcinoma in Chinese are pigmented while this subtype is uncommon in white people. | ||

| Rodent ulcer (also known as a "Jacob's ulcer") | Nodular, with central necrosis.[25]: 748 [26]: 647 | Generally a large skin lesion with central necrosis.[25]: 748 [26]: 647 | |

| Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus | Anastomosing epithelial strands in a fenestrated pattern[29] | Most commonly occurs on the lower back.[25]: 748 [26]: 648 |  |

| Polypoid basal-cell carcinoma | Exophytic nodules (polyp-like structures) | Generally on head and neck.[26]: 648 | |

| Pore-like basal-cell carcinoma | Resembles an enlarged pore or stellate pit.[26]: 648 | ||

| Aberrant basal-cell carcinoma | Absence of any apparent carcinogenic factor, and occurring in odd sites such as the scrotum, vulva, perineum, nipple, and axilla.[26]: 648 |

Aggressiveness patterns

There are mainly three patterns of aggressiveness, based mainly the cohesion of cancer cells:[30]

| Low-level aggressive pattern | Moderately aggressive pattern | Highly aggressive pattern |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Differential diagnoses

| Differential diagnosis | Pathological Features | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Hair follicles | Peripheral sections may look like nests, but do not display atypia, nuclei are smaller, and serial sections will reveal the rest of the hair follicle. |  |

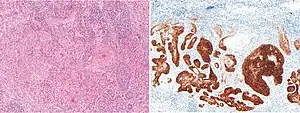

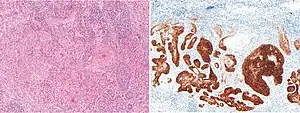

| Squamous-cell carcinoma of the skin | Squamous-cell carcinoma of the skin is generally distinguishable by for example relatively more cytoplasm, horn cyst formation and absence of palisading and cleft formations. Yet, a high prevalence means a relatively high incidence of borderline cases, such as basal-cell carcinoma with squamous cell metaplasia (H&E stain at left in image). BerEP4 staining helps in such cases, staining only basal-cell carcinoma cells (right in image). |  |

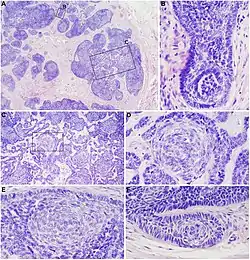

| Trichoblastoma | Absence of cleft, rudimentary hair germs, papillary mesenchymal bodies. |  |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | Lack of basaloid cells disposed in peripheral palisades; adenoid-cystic lesion without connection to the epidermis; absence of artefactual clefts |  |

| Microcystic adnexal carcinoma | Bland keratinocytes, keratin cysts, ductal differentiation. BerEp4- (in 60% of cases),[32] CEA+, EMA+ | |

| Trichoepithelioma[notes 1] | Rims of collagen bundles, calcification, follicular/sebaceous/infundibular differentiation and cut artefacts. Cytokeratin (CK)20+, p75+, Pleckstrin homology-like domain family A member 1 + (PHLDA1+), common acute lymphoblastic leukemiaantigen + (CD10+) in tumor stroma, CK 6-, Ki-67- and Androgen Rceptor- (AR-) | .jpg.webp) |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | Cells arranged in a diffuse, trabecular and/or nested pattern, involving also the subcutis. Mouse Anti-Cytokeratin (CAM) 5.2+, CK20+, S100-, human leukocyte common antigen- ( LCA-), thyroid transcription factor 1- (TTF1-) |  |

Radicality

In suspected but uncertain BCC cells close to the resection margins, immunohistochemistry with BerEp4 can highlight the BCC cells.

Prevention

Basal-cell carcinoma is a common skin cancer and occurs mainly in fair-skinned patients with a family history of this cancer. Sunlight is a factor in about two-thirds of these cancers; therefore, doctors recommend sunscreens with at least SPF 30. However, a Cochrane review examining the effect of solar protection (sunscreen only) in preventing the development of basal-cell carcinoma or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma found that there was insufficient evidence to demonstrate whether sunscreen was effective for the prevention of either of these keratinocyte-derived cancers.[33] The review did ultimately state that the certainty of these results was low, so future evidence could very well alter this conclusion. One-third occur in non-sun-exposed areas; thus, the pathogenesis is more complex than UV exposure as the cause.[12]

The use of a chemotherapeutic agent such as 5-Fluorouracil or imiquimod can prevent the development of skin cancer. It is usually recommended to individuals with extensive sun damage, history of multiple skin cancers, or rudimentary forms of cancer (i.e., solar keratosis).[34] It is often repeated every 2 to 3 years to further decrease the risk of skin cancer.

Treatment

The following methods are employed in the treatment of basal-cell carcinoma (BCC):

Standard surgical excision

Surgery to remove the basal-cell carcinoma affected area and the surrounding skin is thought to be the most effective treatment.[35] A disadvantage with standard surgical excision is a reported higher recurrence rate of basal-cell cancers of the face,[36] especially around the eyelids,[37] nose, and facial structures.[38] There is no clear approach, nor a clear research comparing the effectiveness of Mohs micrographic surgery versus surgical excision for BCC of the eye.[39]

For basal cell carcinoma excisions on the lower lip the wound can be covered with a keystone flap. A keystone flap is achieved by creating a flap below the defect and pulling it superiorly to cover the wound. This can be performed if there is enough skin laxity to cover the defect and adequate blood supply to the flap.[40]

Mohs surgery

For many new (primary) and all recurrent forms of basal cell carcinoma after previous surgery, especially on the head, neck, hands, feet, genitalia and anterior legs (shins), Mohs surgery should be considered.[41][42]

Mohs surgery (or Mohs micrographic surgery) is an outpatient procedure, developed by Frederic E. Mohs in the 1930s,[19] in which the tumor is surgically excised and then immediately examined under a microscope. It is a form of pathology processing called CCPDMA, which means that the entire surgical margin (both edges and deep) is examined. During the surgery, after each removal of tissue and while the patient waits, the tissue is examined for cancer cells. That examination dictates the decision for additional tissue removal. Mohs surgery is also used for squamous-cell carcinoma, melanoma, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, Merkel cell carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and multiple other skin cancers;[42][43] usually with cure rates higher than for other surgical and non-surgical treatments.[43]

An essential aspect of Mohs surgery is that the Mohs surgeon performs the surgery and personally reviews the Mohs pathology slides.[42] Most standard excisions done in an office setting are sent to an outside laboratory for standard bread loafing method of processing.[44] With this method, it is likely that less than 5% of the surgical margin is examined, as each slice of tissue is only 6 micrometres thick, about 3 to 4 serial slices are obtained per section, and only about 3 to 4 sections are obtained per specimen.[45]

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery is an old modality for the treatment of many skin cancers. When accurately utilized with a temperature probe and cryotherapy instruments, it can result in very good cure rate. Disadvantages include lack of margin control, tissue necrosis, over or under treatment of the tumor, and long recovery time. Overall, there are sufficient data to consider cryosurgery as a reasonable treatment for BCC. There are no good studies, however, comparing cryosurgery with other modalities, particularly with Mohs surgery, excision, or electrodesiccation and curettage so that no conclusion can be made whether cryosurgery is as efficacious as other methods. Also, there is no evidence on whether curetting the lesions before cryosurgery affects the efficacy of treatment.[46] Several textbooks are published on the therapy, and a few physicians still apply the treatment to selected patients.[47]

Electrodesiccation and curettage

Electrodesiccation and curettage (EDC, also known as curettage and cautery, simply curettage)[48] is accomplished by using a round knife, or curette, to scrape away the soft cancer. The skin is then burned with an electric current. This further softens the skin, allowing for the knife to cut more deeply with the next layer of curettage. The cycle is repeated, with a safety margin of curettage of normal skin around the visible tumor. This cycle is repeated 3 to 5 times, and the free skin margin treated is usually 4 to 6 mm. Cure rate is very much user-dependent and depends also on the size and type of tumor. Infiltrative or morpheaform BCCs can be difficult to eradicate with EDC. Generally, this method is used on cosmetically unimportant areas like the trunk (torso). Some physicians believe that it is acceptable to utilize EDC on the face of elderly patients over the age of 70. However, with increasing life expectancy, such an objective criterion cannot be supported. The cure rate can vary, depending on the aggressiveness of the EDC and the free margin treated. Some advocate curettage alone without electrodesiccation, and with the same cure rate.[49]

Chemotherapy

Some superficial cancers respond to local therapy with 5-fluorouracil, a chemotherapy agent. One can expect a great deal of inflammation with this treatment.[50] Chemotherapy often follows Mohs surgery to eliminate the residual superficial basal-cell carcinoma after the invasive portion is removed. 5-fluorouracil has received FDA approval.

Removing the residual superficial tumor with surgery alone can result in large and difficult to repair surgical defects. One often waits a month or more after surgery before starting the inmunotherapy or chemotherapy to make sure the surgical wound has adequately healed. Some people advocate the use of curettage (see EDC below) first, followed by chemotherapy. These experimental procedures are not standard care.[48]

Vismodegib and sonidegib are drugs approved for specially treating BCC, but are expensive and cannot be used in pregnant women.

Itraconazole, traditionally an anti-fungal medication, has also garnered recent attention for its potential use in the treatment of BCC, especially those that cannot be removed surgically. Possessing anti-Hedgehog pathway activity, there is clinical evidence that itraconazole has some efficacy either alone or when combined with vismodegib/sonidegib for primary and recurrent BCC. There is one case report of efficacy in metastatic BCC.[51]

Immunotherapy

This technique uses the body's immune system to kill cancer cells. Improvement of the immune system works its way out up to the cancerous cells and treat the skin cancer.

Topical treatment with 5% Imiquimod cream (IMQ), with five applications per week for six weeks has a reported 70–90% success rate at reducing, even removing, the BCC [basal-cell carcinoma]. Imiquimod has received FDA approval, and topical IMQ is approved by the European Medicines Agency for treatment of small superficial basal-cell carcinoma.[48] Off label use of imiquimod on invasive basal-cell carcinoma has been reported. Imiquimod may be used prior to surgery in order to reduce the size of the carcinoma.

Some advocate the use of imiquimod prior to Mohs surgery to remove the superficial component of the cancer.[52]

Research suggests that treatment using Euphorbia peplus, a common garden weed, may be effective.[53] Australian biopharmaceutical company Peplin[54] is developing this as topical treatment for BCC.

Radiation

Radiation therapy can be delivered either as external beam radiotherapy or as brachytherapy (mostly internal radiotherapy). Although radiotherapy is generally used in older patients who are not candidates for surgery, it is also used in cases where surgical excision will be disfiguring or difficult to reconstruct (especially on the tip of the nose, and the nostril rims). Radiation treatment with external radiation often takes as few as 5 visits to as many as 25 visits. Usually, the more visits scheduled for therapy, the less complication or damage is done to the normal tissue supporting the tumor. Radiotherapy can also be useful if surgical excision has been done incompletely or if the pathology report following surgery suggests a high risk of recurrence, for example if nerve involvement has been demonstrated. Cure rate can be as high as 95% for small tumor, or as low as 80% for large tumors. A variation of an external brachytherapy is the epidermal radioisotope therapy (e.g. with 188Re in form of the Rhenium-SCT). It is used in accordance to the general indications for brachytherapy and especially complex localisations or structures (e.g. earlobe) as well as the genitals.[55]

Usually, recurrent tumors after radiation are treated with surgery, and not with radiation. Further radiation treatment will further damage normal tissue, and the tumor might be resistant to further radiation. Radiation therapy may be contraindicated for treatment of nevoid basal-cell carcinoma syndrome. A 2008 study reported that radiation therapy is appropriate for primary BCCs and recurrent BCCs, but not for BCCs that have recurred following previous radiation treatment.[48]

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a new modality for treatment of basal-cell carcinoma, which is administrated by application of photosensitizers to the target area. When these molecules are activated by light, they become toxic, therefore destroy the target cells. Methyl aminolevulinate is approved by EU as a photosensitizer since 2001. This therapy is also used in other skin cancer types.[56] The 2008 study reported that PDT was a good treatment option for primary superficial BCCs and reasonable for primary low-risk nodular BCCs but a "relatively poor" option for high-risk lesions.[48]

Prognosis

Prognosis is excellent if the appropriate method of treatment is used in early primary basal-cell cancers. Recurrent cancers are much harder to cure, with a higher recurrent rate with any methods of treatment. Although basal-cell carcinoma rarely metastasizes, it grows locally with invasion and destruction of local tissues. The cancer can impinge on vital structures like nerves and result in loss of sensation or loss of function or rarely death. The vast majority of cases can be successfully treated before serious complications occur. The recurrence rate for the above treatment options ranges from 50 percent to 1 percent or less.

Epidemiology

Basal-cell cancer is a very common skin cancer. It is much more common in fair-skinned individuals with a family history of basal-cell cancer and increases in incidence closer to the equator or at higher altitude. It is very common among elderly people over the age of 80.[57] There are approximately 800,000[58] new cases yearly in the United States alone. Up to 30% of white people develop basal-cell carcinomas in their lifetime.[59] In Canada, the most common skin cancer is basal-cell carcinoma (as much as one third of all cancer diagnoses), affecting 1 in 7 individuals over a lifetime.[60]

In the United States approximately 3 out of 10 White people develop a basal-cell carcinoma during their lifetime.[59] This tumor accounts for approximately 70% of non-melanoma skin cancers. In 80 percent of all cases, basal-cell carcinoma affects the skin of head and neck.[59] Furthermore, there appears to be an increase in the incidence of basal-cell cancer of the trunk in recent years.[59]

Most sporadic BCC arises in small numbers on sun-exposed skin of people over age 50, although younger people may also be affected. The development of multiple basal-cell cancer at an early age could be indicative of nevoid basal-cell carcinoma syndrome, also known as Gorlin Syndrome.[61]

Notes

- Desmoplastic tricoepithelioma is particularly similar to basal-cell carcinoma.

References

- "Skin Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". NCI. 2013-10-25. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- Gandhi SA, Kampp J (November 2015). "Skin Cancer Epidemiology, Detection, and Management". The Medical Clinics of North America. 99 (6): 1323–35. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.06.002. PMID 26476255.

- "Skin Cancer Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 21 June 2017. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- Krutmann J, Humbert P (2010). Nutrition for Healthy Skin: Strategies for Clinical and Cosmetic Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 31. ISBN 9783642122644. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.14. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - Cakir BÖ, Adamson P, Cingi C (November 2012). "Epidemiology and economic burden of nonmelanoma skin cancer". Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 20 (4): 419–22. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2012.07.004. PMID 23084294.

- Gallagher RP, Lee TK, Bajdik CD, Borugian M (2010). "Ultraviolet radiation". Chronic Diseases in Canada. 29 Suppl 1: 51–68. doi:10.24095/hpcdp.29.S1.04. PMID 21199599.

The major source of ultraviolet radiation is solar radiation or sunlight. However, exposure to artificial sources particularly through tanning salons is becoming more important in terms of human health effects, as use of these facilities by young people, [sic] has increased.

- Jou PC, Feldman RJ, Tomecki KJ (June 2012). "UV protection and sunscreens: what to tell patients". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 79 (6): 427–36. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.11110. PMID 22660875. S2CID 44457153.

- "Skin Cancer Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 21 June 2017. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- Dubas LE, Ingraffea A (February 2013). "Nonmelanoma skin cancer". Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 21 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2012.10.003. PMID 23369588.

- "Genetics of Skin Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 2009-07-29. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- "Basal Cell Carcinoma - Skin Disorders". MSD Manual Consumer Version.

- Boettler MA, Shahwan KT, Abidi NY, Carr DR (2022). "Trichoblastic carcinoma: a comprehensive review of the literature". Arch Dermatol Res. 314 (5): 399–403. doi:10.1007/s00403-021-02241-y. PMID 33993349. S2CID 234598207.

- Laffay L, Depaepe L, d'Hombres A, Balme B, Thomas L, De Bari B (2012). "Histological features and treatment approach of trichoblastic carcinomas: from a case report to a review of the literature". Tumori. 98 (2): 46e–49e. doi:10.1700/1088.11948. PMID 22678003.

- Cribier B (2018). "From basal cell carcinoma to trichoblastic tumors: a diagnostic challenge". Ann Dermatol Venereol (in French). 145 Suppl 5: VS3–VS11. doi:10.1016/S0151-9638(18)31254-7. PMID 30477681. S2CID 81618758.

- Ackerman AB, Kerl H, Sánchez J, Guo Y (2000). "Basal-cell carcinoma: integration unifying concept". A clinical atlas of 101 common skin diseases : with histopathologic correlation. New York: Ardor Scribendi. ISBN 978-1-893357-10-5.

- Fusco N, Lopez G, Gianelli U (September 2015). "Basal-Cell Carcinoma and Seborrheic Keratosis: When Opposites Attract". International Journal of Surgical Pathology. 23 (6): 464. doi:10.1177/1066896915593802. PMID 26135529. S2CID 206650583.

- Epstein EH, Shepard JA, Flotte TJ (January 2008). "Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 3-2008. An 80-year-old woman with cutaneous basal-cell carcinomas and cysts of the jaws". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (4): 393–401. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc0707893. PMID 18216361.

- "What Is Basal Cell Cancer". SkinCancerGuide. Archived from the original on 2009-03-01. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- Ferrante di Ruffano L, Dinnes J, Chuchu N, Bayliss SE, Takwoingi Y, Davenport C, et al. (December 2018). "Exfoliative cytology for diagnosing basal cell carcinoma and other skin cancers in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (12): CD013187. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd013187. PMC 6517175. PMID 30521689.

- Robert S Bader. "Which histologic findings are characteristic of basal cell carcinoma (BCC)?". Medscape. Updated: Feb 21, 2019

- Sunjaya, Anthony Paulo; Sunjaya, Angela Felicia; Tan, Sukmawati Tansil (2017). "The Use of BEREP4 Immunohistochemistry Staining for Detection of Basal Cell Carcinoma". Journal of Skin Cancer. 2017: 1–10. doi:10.1155/2017/2692604. ISSN 2090-2905. PMC 5804366. PMID 29464122.

- Initially copied from: Paolino, Giovanni; Donati, Michele; Didona, Dario; Mercuri, Santo; Cantisani, Carmen (2017). "Histology of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers: An Update". Biomedicines. 5 (4): 71. doi:10.3390/biomedicines5040071. ISSN 2227-9059. PMC 5744095. PMID 29261131.

- Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- James WD, Berger TG, et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- Robert S Bader. "Which histologic findings are characteristic of basal cell carcinoma (BCC)?". Medscape. Updated: Feb 21, 2019

- East, Ellen; Fullen, Douglas R.; Arps, David; Patel, Rajiv M.; Palanisamy, Nallasivam; Carskadon, Shannon; Harms, Paul W. (2016). "Morpheaform Basal Cell Carcinomas With Areas of Predominantly Single-Cell Pattern of Infiltration". The American Journal of Dermatopathology. 38 (10): 744–50. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000541. ISSN 0193-1091. PMID 27043336. S2CID 44948030.

- Haddock ES, Cohen PR (September 2016). "Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus Revisited". Dermatology and Therapy. 6 (3): 347–62. doi:10.1007/s13555-016-0123-8. PMC 4972729. PMID 27329375.

- From the "Glas classification" or "Sabbatsberg classification": Krynitz, B.; Olsson, H.; Lundh Rozell, B.; Lindelöf, B.; Edgren, G.; Smedby, K.E. (2016). "Risk of basal cell carcinoma in Swedish organ transplant recipients: a population-based study". British Journal of Dermatology. 174 (1): 95–103. doi:10.1111/bjd.14153. ISSN 0007-0963. PMID 26333521. S2CID 43844922.

- Yonan, Yousif; Maly, Connor; DiCaudo, David; Mangold, Aaron; Pittelkow, Mark; Swanson, David (2019). "Dermoscopic Description of Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus with Negative Network". Dermatology Practical & Conceptual. 9 (3): 246–47. doi:10.5826/dpc.0903a23. ISSN 2160-9381. PMC 6659602. PMID 31384511. Creative Commons Attribution License

- Inskip, Mike; Magee, Jill (2015). "Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the cheek – a case report with dermatoscopy and dermatopathology". Dermatology Practical & Conceptual. 5 (1): 43–46. doi:10.5826/dpc.0501a07. ISSN 2160-9381. PMC 4325690. PMID 25692080.

- Sánchez G, Nova J, Rodriguez-Hernandez AE, Medina RD, Solorzano-Restrepo C, Gonzalez J, Olmos M, Godfrey K, Arevalo-Rodriguez I (July 2016). "Sun protection for preventing basal-cell and squamous cell skin cancers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (9): CD011161. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011161.pub2. PMC 6457780. PMID 27455163.

- Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, Marcolivio K, Means AD, Leader NF, Shaw FM, Hogan D, Eilers D, Swetter SM, Chen SC, Jacob SE, Warshaw EM, Stricklin GP, Dellavalle RP, Sidhu-Malik N, Konnikov N, Werth VP, Keri JE, Robinson-Bostom L, Ringer RJ, Lew RA, Ferguson R, DiGiovanna JJ, Huang GD (February 2018). "Chemoprevention of Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinoma With a Single Course of Fluorouracil, 5%, Cream: A Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA Dermatology. 154 (2): 167–74. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.3631. PMC 5839275. PMID 29299592.

- Thomson, Jason; Hogan, Sarah; Leonardi-Bee, Jo; Williams, Hywel C.; Bath-Hextall, Fiona J. (November 17, 2020). "Interventions for basal cell carcinoma of the skin". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (12): CD003412. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003412.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8164471. PMID 33202063.

- Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers (PDF). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2009. p. 38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-27.

- Sigurdsson H, Agnarsson BA (August 1998). "Basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Risk of recurrence according to adequacy of surgical margins". Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 76 (4): 477–80. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760416.x. PMID 9716337.

- Farhi D, Dupin N, Palangié A, Carlotti A, Avril MF (October 2007). "Incomplete excision of basal cell carcinoma: rate and associated factors among 362 consecutive cases". Dermatologic Surgery. 33 (10): 1207–14. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33255.x. PMID 17903153. S2CID 19202086.

- Narayanan K, Hadid OH, Barnes EA (December 2014). "Mohs micrographic surgery versus surgical excision for periocular basal-cell carcinoma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD007041. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007041.pub4. PMC 7390281. PMID 25503105.

- , Hallock G. Basal Cell Carcinoma Excision from Lower Lip with Keystone Flap Reconstruction. J Med Ins. 2020;2020(290.6) doi:https://jomi.com/article/290.6

- Bichakjian, CK; Olencki, T; Olencki, SZ (2016). "Basal Cell Skin Cancer, Version 1.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology". J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 14 (May): 574–597. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2016.0065. PMID 27160235. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- Ad Hoc Task Force; Connolly, SM; Baker, DR; Coldiron, BM (2012). "AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery". J Am Acad Dermatol. 67 (4): 531–550. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.009. PMID 22959232. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- Mansouri, Bobbak; Bicknell, Lindsay M.; Hill, Dane; Walker, Gregory D.; Fiala, Katherine; Housewright, Chad (2017-08-01). "Mohs Micrographic Surgery for the Management of Cutaneous Malignancies". Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. Facial Reconstruction Post-Mohs Surgery. 25 (3): 291–301. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2017.03.002. ISSN 1064-7406. PMID 28676157.

- Lane JE, Kent DE (2005). "Surgical margins in the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer and mohs micrographic surgery". Current Surgery. 62 (5): 518–26. doi:10.1016/j.cursur.2005.01.003. PMID 16125611.

- Maloney ME, Torres A, Hoffman TJ (1999). Surgical Dermatopathology. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-86542-299-5.

- Kokoszka A, Scheinfeld N (June 2003). "Evidence-based review of the use of cryosurgery in treatment of basal-cell carcinoma". Dermatologic Surgery. 29 (6): 566–71. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.291511.x. PMID 12786697.

- "Understanding Actinic Keratosis – Treatment". Web MD. Archived from the original on 2007-08-11. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- Telfer NR, Colver GB, Morton CA (July 2008). "Guidelines for the management of basal-cell carcinoma". The British Journal of Dermatology. 159 (1): 35–48. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08666.x. PMID 18593385. S2CID 12365983.

- Barlow JO, Zalla MJ, Kyle A, DiCaudo DJ, Lim KK, Yiannias JA (June 2006). "Treatment of basal cell carcinoma with curettage alone". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 54 (6): 1039–45. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.01.041. PMID 16713459.

- Archived 2009-05-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Ip KH, McKerrow K (2021). "Itraconazole in the treatment of basal cell carcinoma: A case-based review of the literature". Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 62 (3): 394–397. doi:10.1111/ajd.13655. PMID 34160824. S2CID 235608763.

- Butler DF, Parekh PK, Lenis A (January 2009). "Imiquimod 5% cream as adjunctive therapy for primary, solitary, nodular nasal basal-cell carcinomas before Mohs micrographic surgery: a randomized, double blind, vehicle-controlled study". Dermatologic Surgery. 35 (1): 24–29. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34378.x. PMID 19018814. S2CID 45091789.

- "Peplin's skin cancer gel trial a success". The Age. Melbourne. 1 May 2006. Archived from the original on 16 June 2006.

- Peplin Archived June 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Castellucci, Paolo; Savoia, F.; Farina, A.; Lima, G. M.; Patrizi, A.; Baraldi, C.; Zagni, F.; Vichi, S.; Pettinato, C.; Morganti, A. G.; Strigari, L. (2020-11-02). "High dose brachytherapy with non sealed 188Re (rhenium) resin in patients with non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs): single center preliminary results". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 48 (5): 1511–1521. doi:10.1007/s00259-020-05088-z. ISSN 1619-7089. PMC 8113182. PMID 33140131.

- Peng Q, Juzeniene A, Chen J, Svaasand LO, Warloe T, Giercksky K, Moan J (2008). "Lasers in medicine". Reports on Progress in Physics. 71 (5): 056701. Bibcode:2008RPPh...71e6701P. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/71/5/056701. S2CID 119815301.

- Lubeek SF, van Vugt LJ, Aben KK, van de Kerkhof PC, Gerritsen MP (2017). "The epidemiology and clinicopathological features of basal cell carcinoma in patients 80 years and older: a systematic review". JAMA Dermatol. 153 (1): 71–78. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3628. PMID 27732698. S2CID 8964342.

- Skin Cancer Foundation: Basal-Cell Carcinoma Archived 2006-06-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Wong CS, Strange RC, Lear JT (October 2003). "Basal cell carcinoma". BMJ. 327 (7418): 794–98. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7418.794. PMC 214105. PMID 14525881.

- "Epidemiology of Skin Cancer". BC Cancer Agency. Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- Gorlin, Robert J (2008). "Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma (Gorlin) Syndrome". Neurocutaneous Disorders Phakomatoses and Hamartoneoplastic Syndromes. pp. 669–94. doi:10.1007/978-3-211-69500-5_45. ISBN 978-3-211-21396-4.