Porphyria cutanea tarda

Porphyria cutanea tarda is the most common subtype of porphyria.[1] The disease is named because it is a porphyria that often presents with skin manifestations later in life. The disorder results from low levels of the enzyme responsible for the fifth step in heme production. Heme is a vital molecule for all of the body's organs. It is a component of hemoglobin, the molecule that carries oxygen in the blood.

| Porphyria cutanea tarda | |

|---|---|

| Other names | PCT |

| |

| Blister on the hand of a person with porphyria cutanea tarda | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

Hepatoerythropoietic porphyria has been described as a homozygous form of porphyria cutanea tarda,[2] although it can also be caused if two different mutations occur at the same locus.

Symptoms and signs

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) is recognized as the most prevalent subtype of porphyritic diseases.[3]

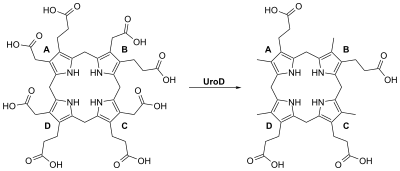

PCT is characterized by onycholysis and blistering of the skin in areas that receive higher levels of exposure to sunlight. The primary cause is a deficiency of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD), a cytosolic enzyme that is a step in the enzymatic pathway that leads to the synthesis of heme. Behind the direct cause there are a number of genetic and environmental risk factors.[4]

Patients who are diagnosed with PCT typically seek treatment following the development of photosensitivities causing blisters and erosions on exposed areas of the skin. This is usually observed in the face, hands, forearms, and lower legs. Healing is slow and leaves scarring. Though blisters are the most common skin manifestations of PCT, other skin manifestations include hyperpigmentation (similar to a tan) and hypertrichosis (mainly on the cheeks) also occur. PCT is a chronic condition, with external symptoms often subsiding and recurring as a result of multiple factors. In addition to the skin lesions, chronic liver disease is very common in patients with sporadic PCT. This involves hepatic fibrosis (scarring of the liver), and inflammation. However, liver problems are less common in patients with the inherited form of the disease.[5] Additionally, patients will often void a wine-red color urine with an increased concentration of uroporphyrin I due to their enzymatic deficiency.[6]

Vitamin, mineral, and enzyme deficiencies

Certain vitamin and minerals deficiencies are common in people with porphyria cutanea tarda. The most common deficiencies are beta-Carotene,[7] retinol,[8] vitamin A[9] and vitamin C. Beta-Carotene is required to synthesize vitamin A and vitamin A is needed to synthesize retinol. A lack of retinol-binding protein is due to a lack of retinol which is required to trigger its production.[9]

Porphyrins interact with iron, absorbing photons to create reactive oxygen species is the mechanism of action causing the itchy, painful blisters of PCT.[7] The reactive oxygen species consume the skin antioxidants beta-carotene, vitamin E, and vitamin C. Supplementation of these three vitamins reduces the oxidation and potentially diminishes the severity of blister formation.[10] No single one of the three vitamins can inhibit the damaging effects of oxidized porphyrins, specifically uroporphyrins and coproporphyrins, but all three working together synergistically are capable of neutralizing their damaging effects.

Genetics

Inherited mutations in the UROD gene cause about 20% of cases (the other 80% of cases do not have mutations in UROD, and are classified as sporadic). UROD makes an enzyme called uroporphyrinogen III decarboxylase, which is critical to the chemical process that leads to heme production. The activity of this enzyme is usually reduced by 50% in all tissues in people with the inherited form of the condition.

Nongenetic factors such as excess iron or partially genetic factors such as alcohol use disorder and others listed above can increase the demand for heme and the enzymes required to make heme. The combination of this increased demand and reduced activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase disrupts heme production and allows byproducts of the process to accumulate in the body, triggering the signs and symptoms of porphyria cutanea tarda.

The HFE gene makes a protein that helps cells regulate the absorption of iron from the digestive tract and into the cells of the body. Certain mutations in the HFE gene cause hemochromatosis (an iron overload disorder). People who have these mutations are also at an increased risk of developing porphyria cutanea tarda.

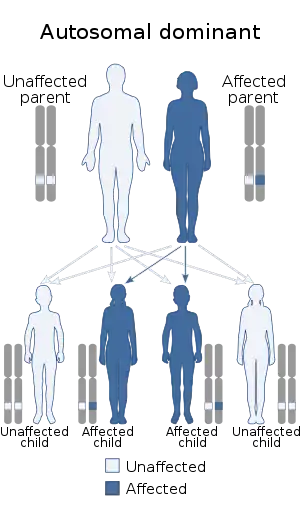

In the 20% of cases where porphyria cutanea tarda is inherited, it is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered gene is sufficient to decrease enzyme activity and cause the signs and symptoms of the disorder.

Other

While inherited deficiencies in uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase often lead to the development of PCT, there are a number of risk factors that can both cause and exacerbate the symptoms of this disease. One of the most common risk factors observed is infection with the Hepatitis C virus.[11] One review of a collection of PCT studies noted Hepatitis C infection in 50% of documented cases of PCT. Additional risk factors include alcohol use disorder, excess iron (from iron supplements as well as cooking on cast iron skillets), and exposure to chlorinated cyclic hydrocarbons and Agent Orange.

It can be a paraneoplastic phenomenon.[12]

Pathogenesis

Porphyria cutanea tarda is primarily caused by uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase deficiency (UROD). Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase occurs in nature as a homodimer of two subunits. It participates in the fifth step in heme synthesis pathway, and is active in the cytosol. This enzymatic conversion results in coproporphyrinogen III as the primary product. This is accomplished by the clockwise removal of the four carboxyl groups present in the cyclic uroporphyrinogen III molecule. Therefore, a deficiency in this enzyme causes the aforementioned buildup of uroporphyrinogen and hepta-carboxylic porphyrinogen, and to a lesser extent hexa-carboxylic porphyrinogen, and penta-carboxylic porphyrinogen in the urine, which can be helpful in the diagnosis of this disorder.[16][17]

The dermatological symptoms of PCT that include blistering and lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin are caused by a buildup of porphyrin compounds (specifically uroporphyrinogen) close to the surface of the skin that have been oxidized by free radicals or sunlight.[18] The oxidized porphyrins initiate degranulation of dermal mast cells,[19] which release proteases that catabolize the surrounding proteins.[20] This begins a cell-mediated positive feedback loop which matches the description of a type 4 delayed hypersensitivity reaction. The resulting blisters, therefore, do not appear immediately but begin to show up 2–3 days after sun exposure. Due to the highly conjugated structure of porphyrins involving alternating single and double carbon bonds, these compounds exhibit a deep purple color, resulting in the discoloration observed in the skin. Excess alcohol intake decreases hepcidin production which leads to increased iron absorption from the gut and an increase in oxidative stress. This oxidative stress then leads to inhibition of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, creating an excess of uroporphyrinogen III which is oxidized from the relatively harmless porphyrinogens into their oxidized porphyrins form.[21] Concentrated instances of oxidative stress (alcohol, physical trauma, psychological stress, etc.) cause the liver to hemorrhage these porphyrins into the blood stream where they are then susceptible to oxidation.

The strong association of PCT with Hepatitis C virus infection is not entirely understood. Studies have suggested that the cytopathic effect of the virus on hepatocytes can lead to the release of free iron. This iron can disrupt the activity of cytochrome p450, releasing activated oxygen species. These can oxidize the UROD substrate uroporphyrinogen, which can result in the inhibition of UROD and lead to deficient activity of this key enzyme.

Excess alcohol use is frequently associated with both inducing PCT[22] and aggravating a preexisting diagnosis of the disorder. It is thought to do so by causing oxidative damage to liver cells, resulting in oxidized species of uroporphyrinogen that inhibit the activity of hepatic UROD. It is also felt to increase the uptake of iron in liver cells, leading to further oxidation of uroporphyrinogen by the release of activated oxygen species. Additionally, exposure to chlorinated cyclic hydrocarbons can lead to a deficiency in the activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, causing the buildup of excess uroporphyrinogen. Additionally, alcohol has been shown to increase the activity of the delta-aminolevulinic acid synthetase (ALA synthetase), the rate-limiting enzymatic step in heme synthesis in the mitochondria, in rats.[23] Therefore, alcohol consumption may increase the production of uroporphyrinogen, exacerbating symptoms in individuals with porphyria cutanea tarda.

Diagnosis

While the most common symptom of PCT is the appearance of skin lesions and blistering, their appearance is not conclusive. Laboratory testing commonly reveals high levels of uroporphyrinogen in the urine, clinically referred to as uroporphyrinogenuria. Additionally, testing for common risk factors such as hepatitis C and hemochromatosis is strongly suggested, as their high prevalence in patients with PCT may require additional treatment. If clinical appearance of PCT is present, but laboratories are negative, the diagnosis of pseudoporphyria should be seriously considered.

Classification

Some sources divide PCT into two types: sporadic and familial.[2] Other sources include a third type,[24] but this is less common.

| Type | OMIM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Type I ("sporadic") | 176090 | Type I porphyria cutanea tarda, the sporadic form, is indicated by UROD deficiency that is observed only in hepatic cells and nowhere else in the body. Genetically, these individuals will not exhibit deficiency in the UROD gene, although other genetic factors such as HFE deficiency (resulting in hemochromatosis and the buildup of iron in the liver) are thought to play a key role. Typically in these individuals, a variety of risk factors such as alcohol use disorder and Hepatitis C virus infection co-occur to result in the clinical manifestation of PCT. |

| Type II ("familial") | 176100 | Patients exhibiting Type II PCT have a specific deficiency in the UROD gene, passed down in an autosomal dominant pattern. Those possessing this deficiency are heterozygous for the UROD gene. They do not show a complete lack of functional uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, only a deficient form of the enzyme that is marked by reduced conversion of uroporphyrinogen to coproporphyrinogen. Therefore, the expression of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase will be reduced throughout the body of these individuals, while it is isolated to the liver in Type I patients. While this genetic deficiency is the main distinction between Type I and Type II PCT, the risk factors mentioned before are often seen in patients presenting with Type II PCT. In fact, many people who possess the deficient UROD gene often go their entire lives without having a clinical manifestation of PCT symptoms. |

| Type III | - | The least common is Type III, which is no different from Type I insofar as the patients possess normal UROD genes. Despite this, Type III PCT is observed in more than one family member, indicating a genetic component unrelated to the expression of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase. |

One study used 74% as the cutoff for UROD activity, with those patients under that number being classified as type II, and those above classified as type III if there was a family history, and type I if there was not.[25]

Genetic variants associated with hemochromatosis have been observed in PCT patients,[13] which may help explain inherited PCT not associated with UROD.

Treatment

Since PCT is a chronic condition, a comprehensive management of the disease is the most effective means of treatment. Primarily, it is key that patients diagnosed with PCT avoid alcohol consumption, iron supplements, excess exposure to sunlight (especially in the summer), as well as estrogen and chlorinated cyclic hydrocarbons, all of which can potentially exacerbate the disorder. Additionally, the management of excess iron (due to the commonality of hemochromatosis in PCT patients) can be achieved through phlebotomy, whereby blood is systematically drained from the patient. A borderline iron deficiency has been found to have a protective effect by limiting heme synthesis. In the absence of iron, which is to be incorporated in the porphyrin formed in the last step of the synthesis, the mRNA of erythroid 5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS-2) is blocked by attachment of an iron-responsive element (IRE) binding cytosolic protein, and transcription of this key enzyme is inhibited.[26]

Low doses of antimalarials can be used.[27] Orally ingested chloroquine is completely absorbed in the gut and is preferentially concentrated in the liver, spleen, and kidneys.[28] They work by removing excess porphyrins from the liver via increasing the excretion rate by forming a coordination complex with the iron center of the porphyrin as well as an intramolecular hydrogen bond between a propionate side chain of the porphyrin and the protonated quinuclidine nitrogen atom of either alkaloid.[29] Due to the presence of the chlorine atom, the entire complex is more water-soluble allowing the kidneys to preferentially remove it from the blood stream and expel it through urination.[28][30][31] Chloroquine treatment can induce porphyria attacks within the first couple of months of treatment due to the mass mobilization of porphyrins from the liver into the blood stream.[28] Complete remission can be seen within 6–12 months as each dose of antimalarial can only remove a finite amount of porphyrins and there are generally decades of accumulation to be cleared. Originally, higher doses were used to treat the condition but are no longer recommended because of liver toxicity.[32][33] Finally, due to the strong association between PCT and Hepatitis C, the treatment of Hepatitis C (if present) is vital to the effective treatment of PCT. Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and venesection are typically employed in the management strategy.[34]

Epidemiology

PCT prevalence is estimated at 1 in 10,000.[35] An estimated 80% of porphyria cutanea tarda cases are sporadic. The exact frequency is not clear because many people with the condition never experience symptoms and those that do are often misdiagnosed with anything ranging from idiopathic photodermatitis and seasonal allergies to hives.

Society and culture

Porphyria cutanea tarda is implicated in the origin of vampire myths. This is because people with the disease tend to avoid the sun due to photosensitivity and may develop disfigurement that eats away their noses, eyelids, lips, and gums giving their teeth a fang-like appearance. It has also been suggested they may have developed a craving for healthy blood to replace their own in a self medicated treatment in prior centuries.

Some folklore scholars claim that this is a mistake, first suggested in the 1990s, because vampires of myth did not have photosensitivity, nor were they described as looking like the modern incarnation of vampires. They were described as unintelligent roaming beings who fed on their victims to the point that they became reddened and heavily bloated, fattened on blood. Fangs were very rarely mentioned. Photosensitivity was not added to the vampire mythology until the 1922 film Nosferatu. Count Dracula of Bram Stroker's novel could walk about freely in daylight unharmed but not as powerful in the book.

Porphyria cutanea tarda is the name of a song by the rock band AFI on their fourth album Black Sails in the Sunset, released on May 18, 1999.

Porphyria cutanea tarda is the disease that both Dabney Pratt and Brother Rush suffer from in Virginia Hamilton's children's novel Sweet Whispers, Brother Rush.

References

- Phillips, J. D.; Bergonia, H. A.; Reilly, C. A.; Franklin, M. R.; Kushner, J. P. (2007). "A porphomethene inhibitor of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase causes porphyria cutanea tarda". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (12): 5079–84. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.5079P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700547104. JSTOR 25427147. PMC 1820519. PMID 17360334.

- "porphyria cutanea tarda" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Danton, Malcolm; Lim, Chang Kee (2007). "Porphomethene inhibitor of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase: Analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry". Biomedical Chromatography. 21 (7): 661–3. doi:10.1002/bmc.860. PMID 17516469.

- Kushner, J P; Barbuto, A J; Lee, G R (1976). "An inherited enzymatic defect in porphyria cutanea tarda: Decreased uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase activity". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 58 (5): 1089–97. doi:10.1172/JCI108560. PMC 333275. PMID 993332.

- Di Padova, C.; Marchesi, L.; Cainelli, T.; Gori, G.; Podenzani, S.A.; Rovagnati, P.; Rizzardini, M.; Cantoni, L. (1983). "Effects of Phlebotomy on Urinary Porphyrin Pattern and Liver Histology in Patients with Porphyria Cutanea Tarda". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 285 (1): 2–12. doi:10.1097/00000441-198301000-00001. PMID 6824014. S2CID 23741767.

- Goljan, E. F. (2011). Pathology (3rd ed., rev. reprint.). Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier.

- Rocchi, E.; Stella, A. M.; Cassanelli, M.; Borghi, A.; Nardella, N.; Seium, Y.; Casalgrandi, G. (1 July 1995). "Liposoluble vitamins and naturally occurring carotenoids in porphyria cutanea tarda". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 25 (7): 510–514. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.1995.tb01737.x. PMID 7556369. S2CID 44998779.

- Rocchi, E.; Casalgrandi, G.; Masini, A.; Giovannini, F.; Ceccarelli, D.; Ferrali, M.; Marchini, S.; Ventura, E. (1 December 1999). "Circulating pro- and antioxidant factors in iron and porphyrin metabolism disorders". Italian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 31 (9): 861–867. PMID 10669994.

- Benoldi, D.; Manfredi, G.; Pezzarossa, E.; Allegra, F. (1 December 1981). "Retinol binding protein in normal human skin and in cutaneous disorders". The British Journal of Dermatology. 105 (6): 659–665. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1981.tb00976.x. PMID 7032574. S2CID 23170672.

- Böhm, F.; Edge, R.; Foley, S.; Lange, L.; Truscott, T. G. (31 December 2001). "Antioxidant inhibition of porphyrin-induced cellular phototoxicity". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 65 (2–3): 177–183. doi:10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00259-7. PMID 11809377.

- Azim, James; McCurdy, H; Moseley, R. H. (2008). "Porphyria cutanea tarda as a complication of therapy for chronic hepatitis C". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (38): 5913–5. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.5913. PMC 2751904. PMID 18855993.

- Sökmen, M; Demirsoy, H; Ersoy, O; Gökdemir, G; Akbayir, N; Karaca, C; Ozdil, K; Kesici, B; Calişkan, C; Yilmaz, B (2007). "Paraneoplastic porphyria cutanea tarda associated with cholangiocarcinoma: Case report". The Turkish Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (3): 200–5. PMID 17891697.

- Frank, J; Poblete-Gutiérrez, P; Weiskirchen, R; Gressner, O; Merk, H. F.; Lammert, F (2006). "Hemochromatosis gene sequence deviations in German patients with porphyria cutanea tarda" (PDF). Physiological Research. 55 Suppl 2: S75–83. doi:10.33549/physiolres.930000.55.S2.75. PMID 17298224. S2CID 1787139.

- Sampietro, M; Fiorelli, G; Fargion, S (1999). "Iron overload in porphyria cutanea tarda". Haematologica. 84 (3): 248–53. PMID 10189391.

- "Porphyria Cutanea Tarda (PCT)". 2020-01-12.

- "Porphyrin Tests". 7 May 2020.

- Jackson, A. H.; Ferramola, A. M.; Sancovich, H. A.; Evans, N; Matlin, S. A.; Ryder, D. J.; Smith, S. G. (1976). "Hepta- and hexa-carboxylic porphyrinogen intermediates in haem biosynthesis". Annals of Clinical Research. 8 Suppl 17: 64–9. PMID 1008499.

- Miller, Dennis M.; Woods, James S. (1993). "Urinary porphyrins as biological indicators of oxidative stress in the kidney". Biochemical Pharmacology. 46 (12): 2235–41. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90614-3. PMID 8274157.

- Brun, Atle; Sandberg, Sverre (1991). "Mechanisms of photosensitivity in porphyric patients with special emphasis on erythropoietic protoporphyria". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 10 (4): 285–302. doi:10.1016/1011-1344(91)80015-A. PMID 1791486.

- Lim, H. W. (1989). "Mechanisms of phototoxicity in porphyria cutanea tarda and erythropoietic protoporphyria". Immunology Series. 46: 671–85. PMID 2488874.

- Ryan Caballes, F.; Sendi, Hossein; Bonkovsky, Herbert L. (2012). "Hepatitis C, porphyria cutanea tarda and liver iron: An update". Liver International. 32 (6): 880–93. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2012.02794.x. PMC 3418709. PMID 22510500.

- Porphyria Cutanea Tarda at eMedicine

- Held, H. (2009). "Effect of Alcohol on the Heme and Porphyrin Synthesis Interaction with Phenobarbital and Pyrazole". Digestion. 15 (2): 136–46. doi:10.1159/000197995. PMID 838185.

- Méndez, M.; Poblete-Gutiérrez, P.; García-Bravo, M.; Wiederholt, T.; Morán-Jiménez, M.J.; Merk, H.F.; Garrido-Astray, M.C.; Frank, J.; Fontanellas, A.; Enríquez De Salamanca, R. (2007). "Molecular heterogeneity of familial porphyria cutanea tarda in Spain: Characterization of 10 novel mutations in the UROD gene". British Journal of Dermatology. 157 (3): 501–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08064.x. hdl:11268/5436. PMID 17627795. S2CID 43785629.

- Cruz-Rojo, J; Fontanellas, A; Morán-Jiménez, M. J.; Navarro-Ordóñez, S; García-Bravo, M; Méndez, M; Muñoz-Rivero, M. C.; De Salamanca, R. E. (2002). "Precipitating/aggravating factors of porphyria cutanea tarda in Spanish patients". Cellular and Molecular Biology (Noisy-le-Grand, France). 48 (8): 845–52. PMID 12699242.

- Thunell, S (2000). "Porphyrins, porphyrin metabolism and porphyrias. I. Update". Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. 60 (7): 509–40. doi:10.1080/003655100448310. PMID 11202048. S2CID 8470078.

- Singal, Ashwani K.; Kormos–Hallberg, Csilla; Lee, Chul; Sadagoparamanujam, Vaithamanithi M.; Grady, James J.; Freeman, Daniel H.; Anderson, Karl E. (2012). "Low-Dose Hydroxychloroquine is as Effective as Phlebotomy in Treatment of Patients with Porphyria Cutanea Tarda". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 10 (12): 1402–9. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.038. PMC 3501544. PMID 22985607.

- "Enforcement Reports". www.accessdata.fda.gov.

- De Villiers, Katherine A.; Gildenhuys, Johandie; Le Roex, Tanya (2012). "Iron(III) Protoporphyrin IX Complexes of the Antimalarial Cinchona Alkaloids Quinine and Quinidine". ACS Chemical Biology. 7 (4): 666–71. doi:10.1021/cb200528z. PMID 22276975.

- Asghari-Khiavi, Mehdi; Vongsvivut, Jitraporn; Perepichka, Inna; Mechler, Adam; Wood, Bayden R.; McNaughton, Don; Bohle, D. Scott (2011). "Interaction of quinoline antimalarial drugs with ferriprotoporphyrin IX, a solid state spectroscopy study". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 105 (12): 1662–9. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.08.005. PMID 22079977.

- Alumasa, John N.; Gorka, Alexander P.; Casabianca, Leah B.; Comstock, Erica; De Dios, Angel C.; Roepe, Paul D. (2011). "The hydroxyl functionality and a rigid proximal N are required for forming a novel non-covalent quinine-heme complex". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 105 (3): 467–75. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.08.011. PMC 3010338. PMID 20864177.

- Sweeney, G. D.; Saunders, S. J.; Dowdle, E. B.; Eales, L (1965). "Effects of Chloroquine on Patients with Cutaneous Porphyria of the "symptomatic" Type". British Medical Journal. 1 (5445): 1281–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5445.1281. PMC 2166040. PMID 14278818.

- Scholnick, Perry L.; Epstein, John; Marver, Harvey S. (1973). "The Molecular Basis of the Action of Chloroquine in Porphyria Cutanea Tarda". Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 61 (4): 226–32. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12676478. PMID 4744026.

- Sarkany, R. P. E. (2001). "The management of porphyria cutanea tarda". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 26 (3): 225–32. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00825.x. PMID 11422163. S2CID 35585037.

- Arceci, Robert.; Hann, Ian M.; Smith, Owen P. (2006). Pediatric hematolog. Malden MA: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-3400-2.

External links

- Porphyria cutanea tarda at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases