Health belief model

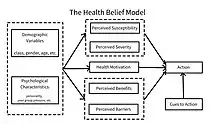

The health belief model (HBM) is a social psychological health behavior change model developed to explain and predict health-related behaviors, particularly in regard to the uptake of health services.[1][2] The HBM was developed in the 1950s by social psychologists at the U.S. Public Health Service[2][3] and remains one of the best known and most widely used theories in health behavior research.[4][5] The HBM suggests that people's beliefs about health problems, perceived benefits of action and barriers to action, and self-efficacy explain engagement (or lack of engagement) in health-promoting behavior.[2][3] A stimulus, or cue to action, must also be present in order to trigger the health-promoting behavior.[2][3]

History

One of the first theories of health behavior,[5] the HBM was developed in 1950s by social psychologists Irwin M. Rosenstock, Godfrey M. Hochbaum, S. Stephen Kegeles, and Howard Leventhal at the U.S. Public Health Service.[4][6] At that time, researchers and health practitioners were worried because few people were getting screened for tuberculosis(TB), even if mobile X-ray cars went to neighborhoods.[7] The HBM has been applied to predict a wide variety of health-related behaviors such as being screened for the early detection of asymptomatic diseases[2] and receiving immunizations.[2] More recently, the model has been applied to understand intentions to vaccinate (e.g. COVID-19),[8] responses to symptoms of disease,[2] compliance with medical regimens,[2] lifestyle behaviors (e.g., sexual risk behaviors),[6] and behaviors related to chronic illnesses,[2] which may require long-term behavior maintenance in addition to initial behavior change.[2] Amendments to the model were made as late as 1988 to incorporate emerging evidence within the field of psychology about the role of self-efficacy in decision-making and behavior.[5][6]

Theoretical constructs

The HBM theoretical constructs originate from theories in Cognitive Psychology.[7] In early twentieth century, cognitive theorists believed that reinforcements operated by affecting expectations rather than by affecting behavior straightly.[9] Mental processes are severe consists of cognitive theories that are seen as expectancy-value models, because they propose that behavior is a function of the degree to which people value a result and their evaluation of the expectation, that a certain action will lead that result.[10][11] In terms of the health-related behaviors, the value is avoiding sickness. The expectation is that a certain health action could prevent the condition for which people consider they might be at risk.[7]

The following constructs of the HBM are proposed to vary between individuals and predict engagement in health-related behaviors.[2]

Perceived susceptibility

Perceived susceptibility refers to subjective assessment of risk of developing a health problem.[2][3][6] The HBM predicts that individuals who perceive that they are susceptible to a particular health problem will engage in behaviors to reduce their risk of developing the health problem.[3] Individuals with low perceived susceptibility may deny that they are at risk for contracting a particular illness.[3] Others may acknowledge the possibility that they could develop the illness, but believe it is unlikely.[3] Individuals who believe they are at low risk of developing an illness are more likely to engage in unhealthy, or risky, behaviors. Individuals who perceive a high risk that they will be personally affected by a particular health problem are more likely to engage in behaviors to decrease their risk of developing the condition.

The combination of perceived severity and perceived susceptibility is referred to as perceived threat.[6] Perceived severity and perceived susceptibility to a given health condition depend on knowledge about the condition.[3] The HBM predicts that higher perceived threat leads to a higher likelihood of engagement in health-promoting behaviors.

Perceived severity

Perceived severity refers to the subjective assessment of the severity of a health problem and its potential consequences.[2][6] The HBM proposes that individuals who perceive a given health problem as serious are more likely to engage in behaviors to prevent the health problem from occurring (or reduce its severity). Perceived seriousness encompasses beliefs about the disease itself (e.g., whether it is life-threatening or may cause disability or pain) as well as broader impacts of the disease on functioning in work and social roles.[2][3][6] For instance, an individual may perceive that influenza is not medically serious, but if he or she perceives that there would be serious financial consequences as a result of being absent from work for several days, then he or she may perceive influenza to be a particularly serious condition.

Through studying Australians and their self-reporting in 2019 of receiving the influenza vaccine, researchers found that by studying perceived severity they could determine the likelihood that Australians would receive the shot. They asked, "On a scale from 0 to 10, how severe do you think the flu would be if you got it?” to measure the perceived severity and they found that 31% perceived the severity of getting the flu as low, 44% as moderate, and 25% as high. Additionally, the researchers found those with a high perceived severity were significantly more likely to have received the vaccine than those with a moderate perceived severity. Furthermore, self-reported vaccination was similar for individuals with low and moderate perceived severity of influenza.[12]

Perceived benefits

Health-related behaviors are also influenced by the perceived benefits of taking action.[6] Perceived benefits refer to an individual's assessment of the value or efficacy of engaging in a health-promoting behavior to decrease risk of disease.[2] If an individual believes that a particular action will reduce susceptibility to a health problem or decrease its seriousness, then he or she is likely to engage in that behavior regardless of objective facts regarding the effectiveness of the action.[3] For example, individuals who believe that wearing sunscreen prevents skin cancer are more likely to wear sunscreen than individuals who believe that wearing sunscreen will not prevent the occurrence of skin cancer

Perceived barriers

Health-related behaviors are also a function of perceived barriers to taking action.[6] Perceived barriers refer to an individual's assessment of the obstacles to behavior change.[2] Even if an individual perceives a health condition as threatening and believes that a particular action will effectively reduce the threat, barriers may prevent engagement in the health-promoting behavior. In other words, the perceived benefits must outweigh the perceived barriers in order for behavior change to occur.[2][6] Perceived barriers to taking action include the perceived inconvenience, expense, danger (e.g., side effects of a medical procedure) and discomfort (e.g., pain, emotional upset) involved in engaging in the behavior.[3] For instance, lack of access to affordable health care and the perception that a flu vaccine shot will cause significant pain may act as barriers to receiving the flu vaccine. In a study about the breast and cervical cancer screening among Hispanic women, perceived barriers, like fear of cancer, embarrassment, fatalistic views of cancer and language, was proved to impede screening.[13]

Modifying variables

Individual characteristics, including demographic, psychosocial, and structural variables, can affect perceptions (i.e., perceived seriousness, susceptibility, benefits, and barriers) of health-related behaviors.[3] Demographic variables include age, sex, race, ethnicity, and education, among others.[3][6] Psychosocial variables include personality, social class, and peer and reference group pressure, among others.[3] Structural variables include knowledge about a given disease and prior contact with the disease, among other factors.[3] The HBM suggests that modifying variables affect health-related behaviors indirectly by affecting perceived seriousness, susceptibility, benefits, and barriers.[3][6]

Cues to action

The HBM posits that a cue, or trigger, is necessary for prompting engagement in health-promoting behaviors.[2][3][4] Cues to action can be internal or external.[2][4] Physiological cues (e.g., pain, symptoms) are an example of internal cues to action.[2][6] External cues include events or information from close others,[2] the media,[4] or health care providers[2] promoting engagement in health-related behaviors. Examples of cues to action include a reminder postcard from a dentist, the illness of a friend or family member, mass media campaigns on health issues, and product health warning labels. The intensity of cues needed to prompt action varies between individuals by perceived susceptibility, seriousness, benefits, and barriers.[3] For example, individuals who believe they are at high risk for a serious illness and who have an established relationship with a primary care doctor may be easily persuaded to get screened for the illness after seeing a public service announcement, whereas individuals who believe they are at low risk for the same illness and also do not have reliable access to health care may require more intense external cues in order to get screened.

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was added to the four components of the HBM (i.e., perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, and barriers) in 1988.[6][14] Self-efficacy refers to an individual's perception of his or her competence to successfully perform a behavior.[6] Self-efficacy was added to the HBM in an attempt to better explain individual differences in health behaviors.[14] The model was originally developed in order to explain engagement in one-time health-related behaviors such as being screened for cancer or receiving an immunization.[3][14] Eventually, the HBM was applied to more substantial, long-term behavior change such as diet modification, exercise, and smoking.[14] Developers of the model recognized that confidence in one's ability to effect change in outcomes (i.e., self-efficacy) was a key component of health behavior change.[6][14] For example, Schmiege et al. found that when dealing with calcium consumption and weight-bearing exercises, self-efficacy was a more powerful predictors than beliefs about future negative health outcomes.[15]

Rosenstock et al. argued that self-efficacy could be added to the other HBM constructs without elaboration of the model's theoretical structure.[14] However, this was considered short-sighted because related studies indicated that key HBM constructs have indirect effects on behavior as a result of their effect on perceived control and intention, which might be regarded as more proximal factors of action.[16]

Empirical support

The HBM has gained substantial empirical support since its development in the 1950s.[2][4] It remains one of the most widely used and well-tested models for explaining and predicting health-related behavior.[4] A 1984 review of 18 prospective and 28 retrospective studies suggests that the evidence for each component of the HBMl is strong.[2] The review reports that empirical support for the HBM is particularly notable given the diverse populations, health conditions, and health-related behaviors examined and the various study designs and assessment strategies used to evaluate the model.[2] A more recent meta-analysis found strong support for perceived benefits and perceived barriers predicting health-related behaviors, but weak evidence for the predictive power of perceived seriousness and perceived susceptibility.[4] The authors of the meta-analysis suggest that examination of potential moderated and mediated relationships between components of the model is warranted.[4]

Several studies have provided empirical support from the chronic illness perspective. Becker et al. used the model to predict and explain a mother's adherence to a diet prescribed for their obese children.[17] Cerkoney et al. interviewed insulin-treated diabetic individuals after diabetic classes at a community hospital. It empirically tested the HBM's association with the compliance levels of persons chronically ill with diabetes mellitus.[18]

Applications

The HBM has been used to develop effective interventions to change health-related behaviors by targeting various aspects of the model's key constructs.[4][14] Interventions based on the HBM may aim to increase perceived susceptibility to and perceived seriousness of a health condition by providing education about prevalence and incidence of disease, individualized estimates of risk, and information about the consequences of disease (e.g., medical, financial, and social consequences).[6] Interventions may also aim to alter the cost-benefit analysis of engaging in a health-promoting behavior (i.e., increasing perceived benefits and decreasing perceived barriers) by providing information about the efficacy of various behaviors to reduce risk of disease, identifying common perceived barriers, providing incentives to engage in health-promoting behaviors, and engaging social support or other resources to encourage health-promoting behaviors.[6] Furthermore, interventions based on the HBM may provide cues to action to remind and encourage individuals to engage in health-promoting behaviors.[6] Interventions may also aim to boost self-efficacy by providing training in specific health-promoting behaviors,[6][14] particularly for complex lifestyle changes (e.g., changing diet or physical activity, adhering to a complicated medication regimen).[14] Interventions can be aimed at the individual level (i.e., working one-on-one with individuals to increase engagement in health-related behaviors) or the societal level (e.g., through legislation, changes to the physical environment, mass media campaigns[19]).[20]

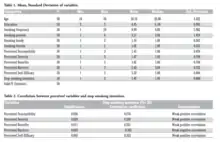

Multiple studies have used the Health Belief Model to understand an individual's intention to change a particular behavior and the factors that influence their ability to do so. Researchers analyzed the correlation between young adult women's intention to stop smoking and their perceived factors in the construction of HBM.[21] The 58 participants were active adult women smokers between 16 and 30 years of age. Table 1 provides more background information while Table 2 shows the correlation between the participants perceived variables and the intention to stop smoking.

Table 2 shows that all variables besides perceived barriers had a weak positive correlation. In regards to perceived susceptibility, the respondents agreed that they were vulnerable to the health and social consequences associated to women smokers; however, they did not fully believe that smoking would trigger such severe health concerns or social consequences therefore they had a low desire to stop smoking. Similarly, with perceived severity the respondents did not view their habits as having a severe consequence therefore they had a low desire to quit. Additionally, the perceived benefits had a weak positive correlation meaning that the individuals saw that the adoption of healthy behaviors would have a beneficial impact on their overall lifestyle. Perceived barriers showed a weak negative correlation meaning that the more barriers the individual associated with stopping smoking then the less likely they were to quit. Lastly, the perceived self-efficacy of respondents were low and this led to a low desire to quit smoking.

The intention to stop smoking among young adult women had a significant correlation with the perceived factors of the Health Belief Model.

Another use of the HBM was in 2016 in a study that was interested in examining the factors associated with physical activity among people with mental illness (PMI) in Hong Kong (Mo et al., 2016). The study used the HBM model because it was one of the most frequently used models to explain health behaviors and the HBM was used as a framework to understand the PMI physical activity levels. The study had 443 PMI complete the survey with the mean age being 45 years old. The survey found that among the HBM variables, perceived barriers were significant in predicting physical activity. Additionally, the research demonstrated that self-efficacy had a positive correlation for physical activity among PMI. These findings support previous literature that self-efficacy and perceived barriers plays a significant role in physical activity and it should be included in interventions. The study also stated that the participants acknowledged that most of their attention is focused on their psychiatric conditions with little focus on their physical health needs.

This study is important to note in regards to the HBM because it illustrates how culture can play a role in this model. The Chinese culture holds different health beliefs than the United States, placing a greater emphasis on fate and the balance of spiritual harmony than on their physical fitness. Since the HBM does not consider these outside variables it highlights a limitation associated with the model and how multiple factors can impact health decisions, not just the ones noted in the model.

Applying the Health Belief Model to Women's Safety Movements

Movements such as the #MeToo movements and current political tensions surrounding abortion laws have moved women's rights and violence against women to the forefront of topical conversation. Additionally, many organizations, such as Women On Guard,[22] have begun to place emphasize on trying to educate women on what measures to take in order to increase their safety when walking alone at night. The murder of Sarah Everard on March 3, 2021, has placed further attention on the need for women to protect themselves and stay vigilant when walking alone at night. Everard was kidnapped and murdered while walking home from work in South London, England. The Health Belief Model can provide insight into the steps that need to be taken in order to reach more women and convince them to take the necessary steps to increase safety when walking alone.

Perceived Susceptibility

As stated, perceived susceptibility refers to how susceptible an individual perceives themselves to be to any given risk. In the case of encountering violence while walking along, research shows that many women have high amounts of perceived susceptibility in regards to how susceptible they believe themselves to be to the risk of being attacked while walking along. Studies show that around 50% of women feel unsafe when walking alone at night[23] Since women may already have increased perceive susceptibility to night-violence, according to the health belief model, they may be more apt to engage in behavior changes to help them increase their safety/ defend themselves.

Perceived Severity

As the statistics on perceived susceptibility demonstrate, many women feel they are at risk for encountering night-violence. Thus, women also have a higher perception of the severity of the violence as stories such as the tragic death of Sarah Everard demonstrate that night-violence attacks can be not only severe, but fatal.

Perceived Benefits & Barriers

As the Health Belief Model states, individuals must consider the potential benefits of adopting the change in behavior that is being suggested to them. In the case of night-violence against women organizations that seek to prevent it do so by using advertising to demonstrate to women that tools such as pocket knives, pepper spray, self-defense classes, alarm systems, and traveling with a "buddy" can outweigh barriers such as the cost, time, and other inconveniences that pursuing these changes in behavior may require. The benefit to implementing these behaviors would be that women could feel more safe when walking alone at night.

Modifying Variable

It is not surprise that the modifying variable of sex plays a large role in applying the Health Belief Model to Women's Safety agendas/ movements. While studies show that around 50% of women feel unsafe walking at night, they also show that fewer than one fifth of men feel the same fear and discomfort[24] Thus, it is evident that the modifying variable of gender plays a large role in how night-time violence is perceived. According to the model, women may be more likely to change their behavior toward preventing night-time violence than men.

Cues to Action

Cues to action are perhaps the most powerful part of the Health Belief Model and of getting individual to change their behavior. In regards to preventing night-time violence against women, stories of the horrific violent acts committed against women while they are walking at night serve as external cues to action that can spur individuals to take the necessary precautions and make the necessary change to their behavior in order to reduce the likelihood of them encountering night-time violence. Cues to action further factor into increased perceived susceptibility and severity of the given risk.

Self Efficacy

Self Efficacy is another important factor both in the Health Belief Model and in behavior change in general. When people believe that they actually have the power to prevent the given risk, then they are more likely to take the appropriate measures to do so. When individuals believe that they cannot change their behavior or prevent the risk no matter what they do, then they are less likely to engage in behavior to stop the risk. This concept factors greatly into initiatives to help women defend themselves against night violence because, based on the statistics, many women do feel that if they carry items such as tasers, pepper spray, or alarms they will be able to defend themselves against attackers. Self-defense classes are also things that organizations offer in order to teach individuals that they have the power to learn how to defend themselves and acquire the proper skills to do so. These classes can help to increase self efficacy. Organizations such as community centers may offer classes along these lines.

The issues of night violence against women is an issue of safety and wellness which makes it applicable to a Health Belief Model Approach. Defense and preparation for night violence can require behavioral changes on behalf of women if they feel that doing so will help them protect themselves should they ever be attacked.

Limitations

The HBM attempts to predict health-related behaviors by accounting for individual differences in beliefs and attitudes.[2] However, it does not account for other factors that influence health behaviors.[2] For instance, habitual health-related behaviors (e.g., smoking, seatbelt buckling) may become relatively independent of conscious health-related decision-making processes.[2] Additionally, individuals engage in some health-related behaviors for reasons unrelated to health (e.g., exercising for aesthetic reasons).[2] Environmental factors outside an individual's control may prevent engagement in desired behaviors.[2] For example, an individual living in a dangerous neighborhood may be unable to go for a jog outdoors due to safety concerns. Furthermore, the HBM does not consider the impact of emotions on health-related behavior.[6] Evidence suggests that fear may be a key factor in predicting health-related behavior.[6]

Alternative factors may predict health behavior, such as outcome expectancy[25] (i.e., whether the person feels they will be healthier as a result of their behavior) and self-efficacy[26] (i.e., the person's belief in their ability to carry out preventive behavior).

The theoretical constructs that constitute the HBM are broadly defined.[4] Furthermore, the HBM does not specify how constructs of the model interact with one another.[4][6] Therefore, different operationalizations of the theoretical constructs may not be strictly comparable across studies.[6][27]

Research assessing the contribution of cues to action in predicting health-related behaviors is limited.[2][3][4][6] Cues to action are often difficult to assess, limiting research in this area.[3][6] For instance, individuals may not accurately report cues that prompted behavior change.[3] Cues such as a public service announcement on television or on a billboard may be fleeting and individuals may not be aware of their significance in prompting them to engage in a health-related behavior.[3][6] Interpersonal influences are also particularly difficult to measure as cues.[3]

Another reason why research does not always support the HBM is that factors other than health beliefs also heavily influence health behavior practices. These factors may include: special influences, cultural factors, socioeconomic status, and previous experiences. Scholars extend the HBM by adding four more variables (self-identity, perceived importance, consideration of future consequences and concern for appearance) as possible determinants of healthy behavior. They prove that consideration of future consequences, self-identity, concern for appearance, perceived importance, self-efficacy, perceived susceptibility are significant determinants of healthy eating behavior that can be manipulated by healthy eating intervention design.[28]

References

- Siddiqui, Taranum Ruba; Ghazal, Saima; Bibi, Safia; Ahmed, Waquaruddin; Sajjad, Shaimuna Fareeha (2016-11-10). "Use of the Health Belief Model for the Assessment of Public Knowledge and Household Preventive Practices in Karachi, Pakistan, a Dengue-Endemic City". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 (11): e0005129. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005129. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 5104346. PMID 27832074.

- Janz, Nancy K.; Marshall H. Becker (1984). "The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later". Health Education & Behavior. 11 (1): 1–47. doi:10.1177/109019818401100101. hdl:2027.42/66877. PMID 6392204. S2CID 10938798.

- Rosenstock, Irwin (1974). "Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model". Health Education & Behavior. 2 (4): 328–335. doi:10.1177/109019817400200403. hdl:10983/3123. S2CID 72995618.

- Carpenter, Christopher J. (2010). "A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior". Health Communication. 25 (8): 661–669. doi:10.1080/10410236.2010.521906. PMID 21153982. S2CID 16228578.

- Glanz, Karen; Bishop, Donald B. (2010). "The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions". Annual Review of Public Health. 31: 399–418. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. PMID 20070207.

- Glanz, Karen; Barbara K. Rimer; K. Viswanath (2008). Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice (PDF) (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. pp. 45–51. ISBN 978-0787996147.

- Glanz, Karen (July 2015). Health behavior: theory, research, and practice. Rimer, Barbara K., Viswanath, K. (Kasisomayajula) (Fifth ed.). San Francisco, CA. ISBN 9781118629055. OCLC 904400161.

- Zampetakis, Leonidas A.; Melas, Christos (2021). "The health belief model predicts vaccination intentions against COVID-19: A survey experiment approach". Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 13 (2): 469–484. doi:10.1111/aphw.12262. ISSN 1758-0854. PMC 8014148. PMID 33634930.

- Lewin, K. (1951). The nature of field theory. In M. H. Marx (Ed.), Psychological theory: Contemporary readings. New York: Macmillan.

- Köhler, Wolfgang (1999). The mentality of apes. ISBN 9780415209793. OCLC 1078926886.

- Lewin, K., Dembo, T., Festinger, L., & Sears, P. S. (1944). Level of aspiration. In J. Hunt (Ed.), Personality and the behavior disorders (pp. 333–378). Somerset, NJ: Ronald Press.

- Trent, Mallory J.; Salmon, Daniel A.; MacIntyre, C. Raina (2021). "Using the health belief model to identify barriers to seasonal influenza vaccination among Australian adults in 2019". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 15 (5): 678–687. doi:10.1111/irv.12843. PMC 8404057. PMID 33586871.

- Austin, Latoya T et al. “Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening in Hispanic Women: a Literature Review Using the Health Belief Model.” Women’s Health Issues 12.3 (2002): 122–128. Web.

- Rosenstock, Irwin M.; Strecher, Victor J.; Becker, Marshall H. (1988). "Social learning theory and the health belief model". Health Education & Behavior. 15 (2): 175–183. doi:10.1177/109019818801500203. hdl:2027.42/67783. PMID 3378902. S2CID 15513907.

- Schmiege, S.J., Aiken, L.S., Sander, J.L. and Gerend, M.A. (2007) Osteoporosis prevention among young women: psychological models of calcium consumption and weight bearing exercise, Health Psychology, 26, 577–87.

- Abraham, Charles, and Sheeran, Paschal. “The Health Belief Model.” Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine. Cambridge University Press, 2001. 97–102. Web.

- Becker, Marshall et al. “The Health Belief Model and Prediction of Dietary Compliance: A Field Experiment.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 18.4 (1977): 348–366. Web.

- Cerkoney, K A, Hart, L K, and Cerkoney, K A. “The Relationship Between the Health Belief Model and Compliance of Persons with Diabetes Mellitus.” Diabetes care 3.5 (1980): 594–598. Web.

- Saba, Walter. "Mass Media and Health Beliefs: Using Media Campaigns to Promote Preventive Behavior".

- Stretcher, Victor J.; Irwin M. Rosenstock (1997). "The health belief model". In Andrew Baum (ed.). Cambridge handbook of psychology, health and medicine. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 113–117. ISBN 978-0521430739.

- Pribadi, Eko Teguh; Devy, Shrimarti Rukmini (2020-07-03). "Application of the Health Belief Model on the Intention to Stop Smoking Behavior among Young Adult Women". Journal of Public Health Research. 9 (2): jphr.2020.1817. doi:10.4081/jphr.2020.1817. ISSN 2279-9036. PMC 7376467. PMID 32728563.

- url=https://www.womenonguard.com/blog/2020/08/06/7-crucial-safety-tips-for-women-walking-alone-at-night/

- "Half of women feel unsafe walking alone after dark, says ONS". Independent.co.uk. 24 August 2021.

- "Half of women feel unsafe walking alone after dark, says ONS". Independent.co.uk. 24 August 2021.

- Schwarzer, Ralf (April 2001). "Social-Cognitive Factors in Changing Health-Related Behaviors". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 10 (2): 47–51. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00112. S2CID 145114248.

- Seyde, Erwin; Taal, Erik; Wiegman, Oene (1990). "Risk-appraisal, outcome and self-efficacy expectancies: Cognitive factors in preventive behaviour related to cancer". Psychology & Health. 4 (2): 99–109. doi:10.1080/08870449008408144.

- Maiman, Lois A.; Marshall H. Becker; John P. Kirscht; Don P. Haefner; Robert H. Drachman (1977). "Scales for Measuring Health Belief Model Dimensions: A Test of Predictive Value, Internal Consistency, and Relationships Among Beliefs". Health Education & Behavior. 5 (3): 215–230. doi:10.1177/109019817700500303. PMID 924795. S2CID 27477189.

- Orji, Rita, Vassileva, Julita, and Mandryk, Regan. “Towards an Effective Health Interventions Design: An Extension of the Health Belief Model.” Online journal of public health informatics 4.3 (2012): n. pag. Web.