Population health

Population health has been defined as "the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group".[1] It is an approach to health that aims to improve the health of an entire human population. It has been described as consisting of three components. These are "health outcomes, patterns of health determinants, and policies and interventions".[1]

A priority considered important in achieving the aim of population health is to reduce health inequities or disparities among different population groups due to, among other factors, the social determinants of health (SDOH). The SDOH include all the factors (social, environmental, cultural and physical) that the different populations are born into, grow up and function with throughout their lifetimes which potentially have a measurable impact on the health of human populations.[2] The population health concept represents a change in the focus from the individual-level, characteristic of most mainstream medicine. It also seeks to complement the classic efforts of public health agencies by addressing a broader range of factors shown to impact the health of different populations. The World Health Organization's Commission on Social Determinants of Health, reported in 2008, that the SDOH factors were responsible for the bulk of diseases and injuries and these were the major causes of health inequities in all countries.[3] In the US, SDOH were estimated to account for 70% of avoidable mortality.[4]

From a population health perspective, health has been defined not simply as a state free from disease but as "the capacity of people to adapt to, respond to, or control life's challenges and changes".[5] The World Health Organization (WHO) defined health in its broader sense in 1946 as "a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity."[6][7]

Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020 is a web site sponsored by the US Department of Health and Human Services, representing the cumulative effort of 34 years of interest by the Surgeon General's office and others. It identifies 42 topics considered social determinants of health and approximately 1200 specific goals considered to improve population health. It provides links to the current research available for selected topics and identifies and supports the need for community involvement considered essential to address these problems realistically.[8]

Economic inequality

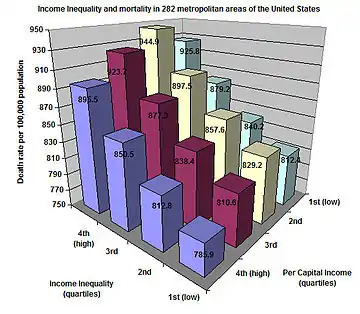

Recently, there has been increasing interest from epidemiologists on the subject of economic inequality and its relation to the health of populations. There is a very robust correlation between socioeconomic status and health. This correlation suggests that it is not only the poor who tend to be sick when everyone else is healthy, given that conditions such as heart disease, ulcers, type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, certain types of cancer, and premature aging are present in all socioeconomic levels. Despite the reality of the SES Gradient, there is debate as to its cause. A number of researchers (A. Leigh, C. Jencks, A. Clarkwest—see also Russell Sage working papers) see a definite link between economic status and mortality due to the greater economic resources of the better-off, but they find little correlation due to social status differences.

Other researchers such as Richard G. Wilkinson, J. Lynch, and G.A. Kaplan have found that socioeconomic status strongly affects health even when controlling for economic resources and access to health care. Most famous for linking social status with health are the Whitehall studies—a series of studies conducted on civil servants in London. The studies found that, despite the fact that all civil servants in England have the same access to health care, there was a strong correlation between social status and health. The studies found that this relationship stayed strong even when controlling for health-affecting habits such as exercise, smoking and drinking. Furthermore, it has been noted that no amount of medical attention will help decrease the likelihood of someone getting type 1 diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis—yet both are more common among populations with lower socioeconomic status. Lastly, it has been found that amongst the wealthiest quarter of countries on earth (a set stretching from Luxembourg to Slovakia) there is no relation between a country's wealth and general population health—suggesting that past a certain level, absolute levels of wealth have little impact on population health, but relative levels within a country do. The concept of psychosocial stress attempts to explain how psychosocial phenomena such as status and social stratification can lead to the many diseases associated with the SES gradient. Higher levels of economic inequality tend to intensify social hierarchies and generally degrades the quality of social relations—leading to greater levels of stress and stress related diseases. Richard Wilkinson found this to be true not only for the poorest members of society, but also for the wealthiest. Economic inequality is bad for everyone's health. Inequality does not only affect the health of human populations. David H. Abbott at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center found that among many primate species, less egalitarian social structures correlated with higher levels of stress hormones among socially subordinate individuals. Research by Robert Sapolsky of Stanford University provides similar findings.

Geographic Inequality

There is well-documented variation in health outcomes by geographic variation in many countries around the globe. This includes the U.S., with the addition of health care utilization & costs geographic variation, down to the level of Hospital Referral Regions (defined as a regional health care market, which may cross state boundaries, of which there are 306 in the U.S.).[9][10] However, data availability of health indicators for sub-national geographies is limited in both number, data source and geographic scale. Across the 38 OECD countries, region, or equivalent large subnational entities, is the predominant geographic level for both mortality and morbidity indicators. Health indicator availability at smaller geographies was sparse, and varied considerably by geographic definition, health indicator, age range of population and years available. In all cases, geographic boundaries used only administrative definitions.[11]

There is ongoing debate as to the relative contributions of race, gender, poverty, education level and place to these variations. The Office of Epidemiology of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau recommends using an analytic approach (Fixed Effects or hybrid Fixed Effects) to research on health disparities to reduce the confounding effects of neighborhood (geographic) variables on the outcomes.

Subfields

Family planning

Family planning programs (including contraceptives, sexuality education, and promotion of safe sex) play a major role in population health. Family planning is one of the most highly cost-effective interventions in medicine.[14] Family planning saves lives and money by reducing unintended pregnancy and the transmission of sexually transmitted infections.[14]

For example, the United States Agency for International Development lists as benefits of its international family planning program:[15]

- "Protecting the health of women by reducing high-risk pregnancies"

- "Protecting the health of children by allowing sufficient time between pregnancies"

- "Fighting HIV/AIDS through providing information, counseling, and access to male and female condoms"

- "Reducing abortions"

- "Supporting women's rights and opportunities for education, employment, and full participation in society"

- "Protecting the environment by stabilizing population growth"

Mental health

There are three main kinds of population-based approaches to mental health: health care system interventions; public health practice interventions; and social, economic, and environmental policy interventions. Health care system interventions are mediated by the health care system and hospital leaders. Examples of these interventions include enhancing the efficacy of clinical mental health services, providing consultations and training for community partners, and sharing aggregate health data to inform policy, practice, and planning for public mental health. Public health practice interventions are mediated by public health department officials. These interventions include advocating for policy changes, initiating public service announcements to reduce the stigma of mental illness, and conducting outreach to increase the accessibility of community mental health resources. Elected officials and administrative policy makers implement social, economic, and environmental policy interventions. These can include reducing financial and housing insecurity, changing the built environment to increase urban green space and decrease nighttime noise pollution, and reducing structural stigma directed at those with mental illness.[16]

Population health management (PHM)

One method to improve population health is population health management (PHM), which has been defined as "the technical field of endeavor which utilizes a variety of individual, organizational and cultural interventions to help improve the morbidity patterns (i.e., the illness and injury burden) and the health care use behavior of defined populations".[17] PHM is distinguished from disease management by including more chronic conditions and diseases, by use of "a single point of contact and coordination", and by "predictive modeling across multiple clinical conditions".[18] PHM is considered broader than disease management in that it also includes "intensive care management for individuals at the highest level of risk" and "personal health management... for those at lower levels of predicted health risk".[19] Many PHM-related articles are published in Population Health Management, the official journal of DMAA: The Care Continuum Alliance.[20]

The following road map has been suggested for helping healthcare organizations navigate the path toward implementing effective population health management:[21]

- Establish precise patient registries

- Determine patient-provider attribution

- Define precise numerators in the patient registries

- Monitor and measure clinical and cost metrics

- Adhere to basic clinical practice guidelines

- Engage in risk-management outreach

- Acquire external data

- Communicate with patients

- Educate patients and engage with them

- Establish and adhere to complex clinical practice guidelines

- Coordinate effectively between care team and patient

- Track specific outcomes

Healthcare reform and population health

Healthcare reform is driving change to traditional hospital reimbursement models. Prior to the introduction of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), hospitals were reimbursed based on the volume of procedures through fee-for-service models. Under the PPACA, reimbursement models are shifting from volume to value. New reimbursement models are built around pay for performance, a value-based reimbursement approach, which places financial incentives around patient outcomes and has drastically changed the way US hospitals must conduct business to remain financially viable.[22] In addition to focusing on improving patient experience of care and reducing costs, hospitals must also focus on improving the health of populations (IHI Triple Aim[23]).

As participation in value-based reimbursement models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) increases, these initiatives will help drive population health.[24] Within the ACO model, hospitals have to meet specific quality benchmarks, focus on prevention, and carefully manage patients with chronic diseases.[25] Providers get paid more for keeping their patients healthy and out of the hospital.[25] Studies have shown that inpatient admission rates have dropped over the past ten years in communities that were early adopters of the ACO model and implemented population health measures to treat "less sick" patients in the outpatient setting.[26] A study conducted in the Chicago area showed a decline in inpatient utilization rates across all age groups, which was an average of a 5% overall drop in inpatient admissions.[27]

Hospitals are finding it financially advantageous to focus on population health management and keeping people in the community well.[28] The goal of population health management is to improve patient outcomes and increase health capital. Other goals include preventing disease, closing care gaps, and cost savings for providers.[29] In the last few years, more effort has been directed towards developing telehealth services, community-based clinics in areas with high proportion of residents using the emergency department as primary care, and patient care coordinator roles to coordinate healthcare services across the care continuum.[28]

Health can be considered a capital good; health capital is part of human capital as defined by the Grossman model.[30] Health can be considered both an investment good and consumption good.[31] Factors such as obesity and smoking have negative effects on health capital, while education, wage rate, and age may also impact health capital.[31] When people are healthier through preventative care, they have the potential to live a longer and healthier life, work more and participate in the economy, and produce more based on the work done. These factors all have the potential to increase earnings. Some states, like New York, have implemented statewide initiatives to address population health. In New York state there are 11 such programs.[32] These programs work to address the needs of the people in their region, as well as assist their local community based organizations and social services to gather data, address health disparities, and explore evidence-based interventions that will ultimately lead to better health for everyone.

See also

- Auxology

- Community health

- Economic inequality

- Health disparities

- Health impact assessment

- Inequality in disease

- List of countries by income equality

- Population Health Forum

- Social determinants of health

- popHealth

References

- Kindig D, Stoddart G (March 2003). "What is population health?". American Journal of Public Health. 93 (3): 380–3. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.3.380. PMC 1447747. PMID 12604476.

- Social Determinants of Health overview tab.

- Meeting Report of World Conference of Social Determinants of Health held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2008.

- McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR (2002). "The case for more active policy attention to health promotion". Health Aff (Millwood). 21 (2): 78–93. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.78. PMID 11900188.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). See also National Academies Press free publication: The Future of Public Health in the 21st Century. - Frankish, CJ et al. "Health Impact Assessment as a Tool for Population Health Promotion and Public Policy" Archived 8 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Vancouver: Institute of Health Promotion Research, University of British Columbia, 1996. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- World Health Organization. WHO definition of Health, Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19–22 June 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948. In Grad, Frank P. (2002). "The Preamble of the Constitution of the World Health Organization". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 80 (12): 982. PMC 2567708. PMID 12571728.

- World Health Organization. 2006. Constitution of the World Health Organization – Basic Documents, Forty-fifth edition, Supplement, October 2006.

- Health People 2020

- Chandra, A; Skinner, JS (2004). Geography and Racial Health Disparities, Chapter 16 of Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life (PDF). National Research Council.

- "Data by Region, the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care". Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Murray, Emily T.; Shelton, Nicola; Norman, Paul; Head, Jenny (1 January 2022). "Measuring the health of people in places: A scoping review of OECD member countries". Health & Place. 73: 102731. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102731. ISSN 1353-8292. PMID 34929525. S2CID 245322428.

- Coburn, David; Denny, Keith; Mykhalovskiy, Eric; McDonough, Peggy; Robertson, Ann; Love, Rhonda (2003). "Population Health in Canada: A Brief Critique". American Journal of Public Health. 93 (3): 392–396. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.3.392. PMC 1447750. PMID 12604479.

- Raphael, Dennis; Bryant, Toba (1 June 2002). "The limitations of population health as a model for a new public health". Health Promotion International. 17 (2): 189–199. doi:10.1093/heapro/17.2.189. PMID 11986300.

- Tsui AO, McDonald-Mosley R, Burke AE (April 2010). "Family planning and the burden of unintended pregnancies". Epidemiol Rev. 32 (1): 152–74. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxq012. PMC 3115338. PMID 20570955.

International studies confirm that family planning is among the most cost-effective of all health interventions (80, 81). The cost savings stem from a reduction in unintended pregnancy, as well as a reduction in transmission of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

- USAID. Family planning Archived 15 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- Purtle, Jonathan; Nelson, Katherine L.; Counts, Nathaniel Z.; Yudell, Michael (2 April 2020). "Population-Based Approaches to Mental Health: History, Strategies, and Evidence". Annual Review of Public Health. 41 (1): 201–221. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094247. ISSN 0163-7525. PMC 8896325. PMID 31905323.

- Hillman, Michael. Testimony before the Subcommittee on Health of the House Committee on Ways and Means, hearing on promoting disease management in Medicare Archived 8 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine. 16 April 2002. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- Howe, Rufus, and Christopher Spence. Population health management: Healthways' PopWorks Archived 17 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. HCT Project 2004-07-17, volume 2, chapter 5, pages 291-297. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- Coughlin JF, Pope J, Leedle BR (April 2006). "Old age, new technology, and future innovations in disease management and home health care" (PDF). Home Health Care Management & Practice. 18 (3): 196–207. doi:10.1177/1084822305281955. S2CID 26428539.

- DMAA: The Care Continuum Alliance. Publications. Population Health Management Archived 24 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- Sanders, Dale A Landmark, 12-Point Review of Population Health Management Companies. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- "The Revised Medicare ACO Program: More Options … And More Work Ahead". Health Affairs. 2015. doi:10.1377/forefront.20150616.048573. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- "The IHI Triple Aim". www.ihi.org. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- DeVore S, Champion RW (2011). "Driving Population Health Through Accountable Care Organizations". Health Affairs. 30 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0935. PMID 21209436.

- "Accountable Care Organizations, Explained". Kaiser Health News. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- Kutscher B. Outpatient care takes the inside track. Modern Healthcare. 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- "Where Have All The Inpatients Gone? A Regional Study With National Implications". Health Affairs. 2014. doi:10.1377/forefront.20140106.035895.

- "Population Health Management: Hospitals' Changing Employer Role". www.beckershospitalreview.com. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- "What is Population Health Management?". Wellcentive. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- Grossman M (1972). "On the Concept of Health Capital and the Demand for Health". Journal of Political Economy. 80 (2): 223–255. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.604.7202. doi:10.1086/259880. S2CID 27026628.

- Folland S, Goodman A, Stano M. The economics of health and health care (Vol. 6): Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education; 2007.

- "Population Health Improvement Program". www.health.ny.gov. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

Further reading

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ (27 May 2006). "Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data" (PDF). The Lancet. 367 (9524): 1747–1757. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. PMID 16731270. S2CID 22609505. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2009.

External links

- "What is Population Health?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- "Population Health". Public Health Agency of Canada.

- "Population health and health care". Canadian Institute for Health Information.

- Canadian Policy Research Secretariate report on population health

- "Population Health and the Population Health Management Programme". NHS England.

- Population Health Forum website