Health in Kenya

Tropical diseases, especially malaria and tuberculosis, have long been a public health problem in Kenya. In recent years, infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), also has become a severe problem. Estimates of the incidence of infection differ widely.

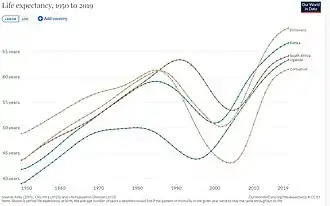

The life expectancy in Kenya in 2016 was 69.0 for females and 64.7 for males. This has been an increment from the year 1990 when the life expectancy was 62.6 and 59.0 respectively.[1] The leading cause of mortality in Kenya in the year 2016 included diarrhoea diseases 18.5%, HIV/AIDs 15.56%, lower respiratory infections 8.62%, tuberculosis 3.69%, ischemic heart disease 3.99%, road injuries 1.47%, interpersonal violence 1.36%. The leading causes of DALYs in Kenya in 2016 included HIV/AIDs 14.65%, diarrhoea diseases 12.45%, lower back and neck pain 2.05%, skin and subcutaneous diseases 2.47%, depression 1.33%, interpersonal violence 1.32%, road injuries 1.3%. The burden of disease in Kenya has mainly been from communicable diseases but it is now shifting to also include the noncommunicable diseases and injuries. As of 2016, the 3 leading causes of death globally were ischemic heart disease 17.33%, stroke 10.11% and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 5.36%.[2]

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative[3] finds that Kenya is fulfilling 84.8% of what they should be fulfilling for the right to health, based on their level of income.[4]

Health status

HIV/AIDS

The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) claimed in 2006 that more than 16 percent of adults in Kenya are HIV-infected.[5] The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) cites the much lower figure of 6.7 percent.[5]

Despite politically charged disputes over the numbers, however, the Kenyan government recently declared HIV/AIDS a national disaster. In 2004 the Kenyan Ministry of Health announced that HIV/AIDS had surpassed malaria and tuberculosis as the leading disease killer in the country. Due largely to AIDS, life expectancy in Kenya has dropped by about a decade. Since 1984 more than 1.5 million Kenyans have died because of HIV/AIDS.[5]

In 2017, the number of people in Kenya living with HIV/AIDs was 1 500 000 and the prevalence rate was 4.8% of the total population. The prevalence rate of women aged 15 to 49 years was 6.2% which was higher than that of men 3.5% in the same age group. The incidence rate was 1.21 per 1000 population among all ages and more than 75% of the total population are on antiretroviral therapy. Globally 36.9 million people were living with HIV by the year 2017, 21.7 million of the people living with HIV were on antiretroviral therapy and the newly infected people for the same year was 1.8 million.[6]

AIDS has contributed significantly to Kenya's dismal ranking in the latest UNDP Human Development Report, whose Human Development Index (HDI) score is an amalgam of gross domestic product per head, figures for life expectancy, adult literacy, and school enrolment. The 2006 report ranked Kenya 152nd out of 177 countries on the HDI and pointed out that Kenya is one of the world's worst performers in infant mortality. Estimates of the infant mortality rate range from 57 to 74 deaths/1,000 live births. The maternal mortality ratio is also among the highest in the world, due in part to female genital mutilation. The practice has been fully prohibited nationwide since 2011.[7]

Malaria

Malaria remains a major public health problem in Kenya and accounts for an estimated 16 percent of outpatient consultations. Malaria transmission and infection risk in Kenya are determined largely by altitude, rainfall patterns, and temperature, which leads to considerable variation in malaria prevalence by season and across geographic regions. Approximately 70 percent of the population is at risk for malaria, with 14 million people in endemic areas, and another 17 million in areas of epidemic and seasonal malaria. All four species of Plasmodium parasites that infect humans occur in Kenya. The parasite Plasmodium falciparum, which causes the most severe form of the disease, accounts for more than 99 percent of infections.[8]

Kenya has made significant progress in the fight against malaria. The Government of Kenya places a high priority on malaria control and tailors its malaria control efforts according to malaria risk to achieve maximum impact. With support from international donors, the Ministry of Health’s National Malaria Control Program has been able to show improvements in coverage of malaria prevention and treatment measures. Recent household surveys show a reduction in malaria parasite prevalence from 11 percent in 2010 to 8 percent in 2015 nationwide, and from 38 percent in 2010 to 27 percent in 2015 in the endemic area near Lake Victoria. The mortality rate in children under five years of age has declined by 55 percent, from 115 deaths per 1,000 live births in the 2003 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) to 52 deaths per 1,000 live births in the 2014 DHS.[8]

Traffic collisions

Apart from major disease killers, Kenya has a serious problem with death in traffic collisions. Kenya used to have the highest rate of road crashes in the world, with 510 fatal crashes per 100,000 vehicles (2004 estimate), as compared to second-ranked South Africa, with 260 fatalities, and the United Kingdom, with 20. In February 2004, in an attempt to improve Kenya's record, the government obliged the owners of the country's 25,000 matatus (minibuses), the backbone of public transportation, to install new safety equipment on their vehicles. Government spending on road projects is also planned.[5] Barack Obama Sr., the father of the former U.S. president, was in several serious drunk driving accidents which paralysed him. He was later killed in a drink driving accident .

Child mortality

The child mortality per 1000 live birth has reduced form 98.1 in 1990 to 51 in 2015, this compares to the global statistics of child mortality which has dropped from 93 in 1990 to 41 in 2016. . The infant mortality rate has also reduced form 65.8 in 1990 to 35.5 in 2015 while the neonatal mortality rate per 1000 live births is 22.2 in 2015.[9]

| 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child mortality | 98.1 | 101 | 62.2 | 51.0 |

| Infant mortality | 65.8 | 66.5 | 42.4 | 35.5 |

| Neonatal mortality | 27.4 | 29.1 | 25.9 | 22.2 |

Maternal and child health care

Maternal mortality is defined as "the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes".[10] Over 500,000 women globally die every year due to maternal causes, and half of all global maternal deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa.[11][12]

The 2010 maternal mortality rate per 100,000 births for Kenya is 530, yet has been shown to be as high as 1000 in the North Eastern Province, for example.[13] This is compared with 413.4 in 2008 and 452.3 in 1990. In Kenya the number of midwives per 1,000 live births is unavailable and the lifetime risk of death for pregnant women 1 in 38.[14] However, generally, the rate of maternal deaths in Kenya has significantly reduced. This can be largely attributed to the success of the Beyond Zero campaign, a charitable organization whose mission is to see total elimination of maternal deaths in Kenya.

Women under 24 years of age are especially vulnerable because the risk of developing complications during pregnancy and childbirth. The burden of maternal mortality extends far beyond the physical and mental health implications. In 1997, the gross domestic product (GDP) loss attributable to MMR per 100,000 live births was $234 US, one of the highest losses compared to other African regions. Additionally, with the annual number of maternal deaths being 6222, the total annual economic loss due to maternal mortality in Kenya was $2240 US, again one of the highest losses compared to other African regions.[15]

Kenya's health infrastructure suffers from urban-rural and regional imbalances, lack of investment, and a personnel shortage, with, for example, one doctor for 10,150 people (as of 2000).[5]

Determinants of maternal mortality and morbidity

The determinants influencing maternal mortality and morbidity can be categorised under three domains: proximate, intermediate, and contextual.[16][17]

Proximate determinants: these refer to those factors that are mostly closely linked to maternal mortality. More specifically, these include pregnancy itself and the development of pregnancy and birth-related or postpartum complications, as well as their management. Based on verbal autopsy reports from women in Nairobi slums, it was noted that most maternal deaths are directly attributed to complications such as haemorrhage, sepsis, eclampsia, or unsafe abortions. Conversely, indirect causes of mortality were noted to be malaria, anaemia, or TB/HIV/AIDS, among others.[18]

Intermediate determinants: these include those determinants related to the access to quality care services, particularly barriers to care such as: health system barriers (e.g. health infrastructure), financial barriers, and information barriers. For example, interview data of women aged 12–54 from the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS), found that the high cost of formal delivery services in hospitals, as well as the cost transportation to these facilities presented formidable barriers to accessing obstetric care.[19] Other intermediate determinants include reproductive health behaviour, such as receiving antenatal care––a strong predictor of later use of formal, skilled care––, and women's health and nutritional status.

Contextual determinants: these refer primarily to the influence of political commitment––policy formulation, for example––, infrastructure, and women's socioeconomic status, including education, income, and autonomy. With regards to political will, a highly contested issue is the legalisation of abortion. The current restrictions on abortions has led to many women receiving the procedure illegally and often via untrained staff. These operations have been estimated to contribute to over 30% of maternal mortalities in Kenya.[20]

Infrastructure refers not only to the unavailability of services in some areas, but also the inaccessibility issues that many women face. In reference to maternal education, women with greater education are more likely to have and receive knowledge about the benefits of skilled care and preventative action—antenatal care use, for example. In addition, these women are also more likely to have access to financial resources and health insurance, as well as being in a better position to discuss the use of household income. This increased decision-making power is matched with a more egalitarian relationship with their husband and an increased sense of self-worth and self-confidence. Income is another strong predictor influencing skilled care use, in particular, the ability to pay for delivery at modern facilities.[21]

Women living in households unable to pay for the costs of transportation, medications, and provider fees were significantly less likely to pursue delivery services at skilled facilities. The impact of income level also influences other sociocultural determinants. For instance, low-income communities are more likely to hold traditional views about birthing, opting away from skilled care use. Similarly, they are also more likely to give women less autonomy in making household and healthcare-related decisions. Thus, these women are not only unable to receive money for care from husbands––who often place greater emphasis on the purchase of food and other items––but are also much less able to demand formal care.[21]

Maternal health in the North-Eastern Province

The North-Eastern Province of Kenya extends over 126, 903 km2 and contains the main districts of Garissa, Ijara, Wajir, and Mandera.[22] This area contains over 21 primary hospitals, 114 dispensaries serving as primary referrals sites, 8 nursing homes with maternity services, 9 health centres, and out of the 45 medical clinics spanning this area, 11 of these clinics specifically have nursing and midwifery services available for mothers[23] However, health disparities exist within these regions, especially among the rural districts of the North-Eastern province. Approximately 80% of the population of the North-Eastern Province of Kenya consists of Somali nomadic pastoralist communities who frequently resettle around these regions. These communities are the most impoverished and marginalised in the region.[24]

Despite the availability of these resources, these services are severely underused in this population. For example, despite the high MMR, many of the women are hesitant to seek delivery assistance under the care of trained birth attendants at these facilities. Instead, many of these women opt to deliver at home, which accounts for the greatest mortality rates in these regions. For example, the Ministry of Health projected that about 500 mothers would use the Garissa Provincial General Hospital by 2012 since it opened in 2007; however, only 60 deliveries occurred at this hospital. Reasons for low attendance include a lack of awareness of these facility's presence, ignorance, and inaccessibility of these services in terms of distance and costs. However, to address some of the accessibility barriers to obtaining care, there are concerted efforts within the community already such as mobile health clinics and waived user fees.[25]

Ethnicity in Relation to Kenya's Health Status

Kenya has a diverse population with upwards of 42 ethnic groups and subgroups, see (Demographics of Kenya). The most prominent groups are the Kikuyu, Luhya, Luo, Kalenjin, and Kamba.[26] The differences in language and culture that come with this extensively diverse population have been coupled with ethnic conflict and favoritism[27] Much of this conflict is rooted in the search for political power as there is a common belief that political power held by the ethnic majority preludes to influence throughout other facets of society.[28] Many researchers argue that political leaders in power will distribute resources to their co-ethnic voters because of their ethnic identity. There are confounding theories that examine the ways in which leaders will or will not achieve this feat, but the overall theory linking ethnic identity with more/better remains the same.[27]In general, researchers have found that an uneven distribution of resources has caused an imbalance of resources and underdevelopment of some regions in the country.[28]Healthcare as a public resource in Kenya is impacted by ethnic favoritism, as those who share co-ethnics with the political leader in power have more opportunities to access said resource due to social inequality.[29]In addition, data shows that ethnicity can impact communication between patients and healthcare providers and a person's overall sense of wellness.

Distribution of Healthcare as a Public Good

Since its independence, Kenya had a highly centralized government that is partially responsible for distributing healthcare resources.[30] Recently, the country implemented a new system in place that requires individual counties to be responsible for the distribution of resources while the national government maintains responsibility for overseeing hospitals and capacity buildings.[26] Much of Kenya’s issues in health inequity can be attributed to economic disadvantages and high poverty levels.[26] In places where healthcare institutions exist, data shows that many individuals do not use them and it was reported that those who live in more affluent urban areas are more likely to report their ills than those who live in rural areas.[30] Hospitals that are overseen by the government are more likely to be found in non-rural regions.[30] This problem has been shown to negatively affect ethnic groups like the Maasai community who rely on the land for their livelihood and are distanced from the urban areas in the country.[26] The benefits of ethnic favoritism also tend to be targeted more toward regions composed of particular ethnic groups rather than specific individuals.[31] Those who live in the targeted regions are more likely to have better access to healthcare.

Interpersonal Interactions in Healthcare

The two officially recognized languages in Kenya are English and Swahili.[32] Swahili is spoken by about two-thirds of the population, and English is heavily used and taught. Both of these languages are the ones primarily used on government documents or for professional interactions, including healthcare visits.[32] There are several Kenyans who primarily speak their native or regional language in addition to the two national languages.[32] However, those who do not speak the official language may be limited in their access to civil goods.[32] Previous research has shown that the language barriers between patients and doctors can deter patients from accessing healthcare in their communities.[33] Survey accounts report that several patients may feel uncomfortable seeing a doctor from a differing ethnic group because of the difference in language, different style of communication, or perceived bias. However several Kenyans have also shared that they prefer going to professionals from differing ethnic groups to protect their privacy.[33]

Social Capital and Health

Social capital is the perceived agency that someone has in terms of what benefits they can receive from their individual communities and society as a whole.[34] A person's social capital can be influenced by their ethnic identity and how much perceived and literal power they have in relation to the power that their group has. Ethnic favoritism that leads to higher levels of social inequality can be mediated with increased social capital for disadvantaged groups of people.[35] In Kenya, it has been found that increased social capital has a positive correlation with decreased anxiety, stress, and overall health. [34] Social capital, in general, has been shown to foster feelings of trust and reciprocity among individuals in their communities. However, there is also some data to show that social capital within a community can cause anxiety and worry, this is more prominent in communities that rely on each other for resources.[34]

See also

- Healthcare in Kenya

- Recreational drug use in Kenya

- COVID-19 pandemic in Kenya

References

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (2018). IHME. Measuring what matters. University of Washington. Read from http://www.healthdata.org/kenya on 8-09.2018

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (2016). IHME. Measuring what matters. University of Washington. Read from https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ on 8-09.2018

- "Human Rights Measurement Initiative – The first global initiative to track the human rights performance of countries". humanrightsmeasurement.org. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- "Kenya - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- Kenya country profile. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (June 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- UNAIDS (n.d). Epidemic transmission metrics. Read from http://aidsinfo.unaids.org on 08-09-2018

- THE PROHIBITION OF FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION ACT, 2011

- "Kenya" (PDF). President's Malaria Initiative. 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - https://www.gapminder.org/tools on 08-09-2018

- WHO 2012 [www.who.int%2Fhealthinfo%2Fstatistics%2Findmaternalmortality%2Fen%2Findex.html&sa=D&sntz=1&usg=AFQjCNHp-LZx-ozMEQeuaFxcOL2pXgau2A]

- CIDA 2011 cida.gc.ca/acdicida/ACDI-CIDA.nsf/eng/JUD-41183252-2NL Archived 17 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Kirigia, Joses M.; Oluwole, Doyin; Mwabu, Germano M.; Gatwiri, Doris & Kainyu; Kainyu, Lh (2008). "Effects of Maternal Mortality on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the WHO African Region". African Journal of Health Sciences. 13 (1–2): 86–95. doi:10.4314/ajhs.v13i1.30821. PMID 17348747.

- Red Cross 2011

- "The State of the World's Midwifery". United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Ochako et al. (2011). Utilization of maternal health services among young women in Kenya: Insights from the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey, 2003.

- Epuu, K. G. (2010). Determinants of maternal morbidity and mortality Turkana District Kenya (Thesis).

- Warren, Charlotte; Liambila, Wilson (1 January 2004). "Safe Motherhood Demonstration Project, Western Province: Final Report". Reproductive Health. doi:10.31899/rh5.1002.

- Ziraba, Abdhalah Kasiira; Madise, Nyovani; Mills, Samuel; Kyobutungi, Catherine; Ezeh, Alex (22 April 2009). "Maternal mortality in the informal settlements of Nairobi city: what do we know?". Reproductive Health. 6 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-6-6. PMC 2675520. PMID 19386134. S2CID 2320731.

- Essendi, Hildah; Mills, Samuel; Fotso, Jean-Christophe (1 June 2011). "Barriers to Formal Emergency Obstetric Care Services' Utilization". Journal of Urban Health. 88 (2): 356–369. doi:10.1007/s11524-010-9481-1. PMC 3132235. PMID 20700769. S2CID 18731098.

- Brookman-Amissah, Eunice; Moyo, Josephine Banda (January 2004). "Abortion Law Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa: No Turning Back". Reproductive Health Matters. 12 (sup24): 227–234. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(04)24026-5. PMID 15938178. S2CID 30640187.

- Gabrysch, Sabine; Campbell, Oona MR (11 August 2009). "Still too far to walk: Literature review of the determinants of delivery service use". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 9 (1): 34. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-9-34. PMC 2744662. PMID 19671156.

- "KNBS, 2011". Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- "MMS, 2012". Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- USAID, 2010, Kenya-Somalia border conflict analysis

- Boniface, Bosire (12 March 2012). "Kenya's North Eastern Province Battles High Maternal Mortality Rate". Sabahi.

- Mwai, Daniel; Barker, Catherine; Mulaki, Aaron; Dutta, Arin (2014). "DEVOLUTION OF HEALTHCARE IN KENYA: ASSESSING COUNTY HEALTH SYSTEM READINESS IN KENYA: A REVIEW OF SELECTED HEALTH INPUTS" (PDF). doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.36622.87363.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Franck, Raphaël; Rainer, Ilia (May 2012). "Does the Leader's Ethnicity Matter? Ethnic Favoritism, Education, and Health in Sub-Saharan Africa" (PDF). American Political Science Review. 106 (2): 294–325. doi:10.1017/S0003055412000172. S2CID 15227415.

- Nyaura, Jasper Edward (1 June 2018). "Devolved Ethnicity in the Kenya: Social, Economic and Political Perspective". European Review of Applied Sociology. 11 (16): 17–26. doi:10.1515/eras-2018-0002. S2CID 150230348.

- Gutwa Oino, Peter; Ngunzo Kioli, Felix (April 2014). "Ethnicity and Social Inequality: A Source of Under-Development in Kenya". International Journal of Science and Research. 3 (4): 723–729.

- Wamai, Richard G (2009). "The Kenya Health System-Analysis of the situation and enduring challenges" (PDF). Japan Medical Association Journal. 52 (2): 134–140.

- Dickens, Andrew (1 July 2018). "Ethnolinguistic Favoritism in African Politics". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 10 (3): 370–402. doi:10.1257/app.20160066.

- Language and national identity in Africa. Andrew Simpson. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2008. ISBN 978-0-19-153681-6. OCLC 227038652.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Miller, Anne Neville (2010). "Ethnicity and Patient-Doctor Communication in Kenya". African Communication Research. 3: 267–280.

- Musalia, John (1 October 2016). "Social capital and health in Kenya: A multilevel analysis". Social Science & Medicine. 167: 11–19. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.043. PMID 27597538.

- Uphoff, Eleonora P; Pickett, Kate E; Cabieses, Baltica; Small, Neil; Wright, John (2013). "A systematic review of the relationships between social capital and socioeconomic inequalities in health: a contribution to understanding the psychosocial pathway of health inequalities". International Journal for Equity in Health. 12 (1): 54. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-12-54. PMC 3726325. PMID 23870068.

External links

- The State of the World's Midwifery – Kenya Country Profile

.svg.png.webp)