Health in Mali

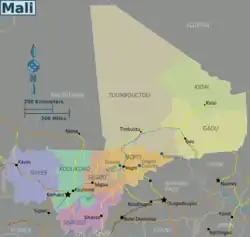

Mali, one of the world’s poorest nations, is greatly affected by poverty, malnutrition, epidemics, and inadequate hygiene and sanitation. Mali's health and development indicators rank among the worst in the world, with little improvement over the last 20 years.[1] Progress is impeded by Mali's poverty[2] and by a lack of physicians.[3] The 2012 conflict in northern Mali exacerbated difficulties in delivering health services to refugees living in the north.[4]

.jpg.webp)

A new measure of expected human capital calculated for 195 countries from 1990 to 2016 and defined for each birth cohort as the expected years lived from age 20 to 64 years and adjusted for educational attainment, learning or education quality, and functional health status was published by The Lancet in September 2018. Mali had the fifth lowest level of expected human capital countries with 3 health, education, and learning-adjusted expected years lived between age 20 and 64 years. This was a notable improvement over 1990 when its score was 0, the lowest of all.[5]

Health infrastructure

Although Mali has its own health care, with a governmental constitution that advocates countrywide health, Mali is heavily dependent upon international development organizations and foreign missionary groups for much of its health care.[6] In 2015, the health expenditure by the government was only 5.8% of GDP.[7]

Hospitals

Medical facilities in Mali are very limited, especially outside of Bamako, and medicines are in short supply.[8]In 2019, there were 1,478 medical facilities in Maili, including 18 government and university hospitals. The additional medical facilities included polyclinics, clinics, and health centers. The other facilities are small health centers and posts.[9] The table below lists the hospitals, region, type, ownership, and coordinates:

| Name | Region | Type | Ownership | Coordinates | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHU[10] Cnos | Bamako | Hospital | Govt. | 12.636701°N 8.00353°W | [9] |

| CHU Gabriel Toure | Bamako | Hospital | Govt. | 12.651171°N 7.99438°W | [9][11][12][13] |

| CHU Point G | Bamako | Hospital | Govt. | 12.669921°N 7.99982°W | [9][11][12][13] |

| Institut d’Ophtalmologie Tropicale de l’Afrique (IOTA) Hopital | Bamako | Hospital | Govt. | 12.652°N 7.99407°W | [9][11][12][13] |

| Mali Gavardo Hopital | Bamako | Hospital | Govt. | 12.58341°N 8.05005°W | [9] |

| Mali Hopital | Bamako | Hospital | Govt. | 12.63035°N 7.9092°W | [9][12][13] |

| Golden Life American Hospital | Bamako | Hospital | Private | 12.623821111221222°N 7.995236859366405°W | [12][14] |

| Pasteur Polyclinic | Bamako | Polyclinic | Private | 12.636837997310593°N 8.020427954049337°W | [13][12] |

| Gao Hopital | Gao | Hospital | Govt. | 16.26849235°N 0.0502213949999°W | [9] |

| Fousseyni Daou Hopital | Kayes | Regional Hospital | Govt. | 14.4489656383°N 11.4348404861°W | [9][15] |

| Kati Hopital | Koulikoro | Hospital | Govt. | 12.71684°N 8.05018°W | [9] |

| Sevare Hopital | Mopti | Hospital | Govt. | 14.52457497°N 4.094687899°W | [9] |

| Somino Dolo Hopital | Mopti | Hospital | Govt. | 14.49661°N 4.19584°W | [9] |

| Nianakoro Fomba Hopital | Segou | Hospital | Govt. | 13.43355°N 6.25017°W | [9] |

| Segou Regional Hopital | Segou | Regional Hospital | Govt. | 13.44288°N 6.268655°W | [9] |

| Sikasso Hopital | Sikasso | Hospital | Govt. | 11.31604497°N 5.6618404°W | [9][16] |

| Tombouctou Hopital | Tombouctou | Hospital | Govt. | 16.76618535°N 3.007772523°W | [9] |

Physician availability

There are three major public hospitals in the greater Bamako region. However, Mali still lacks a great number of physicians, as there are only .08 physicians per 10 000 citizens.[17] In 2009, there were only 729 physicians in the entire country of more than 10 million people.[2]

Doctors Without Borders

In Northern Mali, there are very little areas in which civilians could ask for medical assistance. Health authorities have proven to be unable to manage epidemics within the populations in northern Mali, and this gap has been filled by the Doctors Without Borders association, also known as Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). Since the coming of the MSF, more than 40,000 children have been protected from malaria and improved regional hospitals. The struggle still remains in the fact that over 40% of people in some regions must walk 9 miles to the nearest health clinic.[18] Much of northern Mali has been afflicted with conflict, resulting in many refugees.

In southern Mali, which is more peaceful, MSF has worked to improve hospital bed numbers and malaria vaccinations.[18]

Governmental actions

In 2009 the government of Mali aided by the Chinese government began construction of a fourth in Missabougou quarter, Bamako, to be named "Hôpital du Mali".[19] However, the government as invested minimally into health (2.9%), rendering most major projects unable to be carried out.[20] Organizations like the Health Policy Project (HPP) have been pushing for more government resources for health.[21] Furthermore, a study by the Infection Control Hospital Epidemiology (ICHE) has determined that help from the World Health Organization in the sanitation and health of Malians was feasible and effective.[22]

Health policy systems

Many African countries have been advocating the implementation of user fees regarding health care within the countries, which would charge citizens based on the health care they received.[23] There has been significant studies to show that such charging results in complicated health and social problems that could have severe consequences in gender equality, household powers, social status, and poverty.[23] Fees also resulted in decreased services in utility and reduced women's health care in various areas such as decision making.[23]

Health care

Although Mali's constitution guarantees the right to proper health,[20] only around 2.9% of the nation's GDP is invested into health care, resulting in the incidence of many disease being too high.[6] Much of what little health care Mali has is focused on to Mali's capitol, Bamako, where around 4000 healthcare workers strive to keep 1.8 million people in good health.[20][24] The rest of the country has less than 3500 healthcare workers in total, meaning that people living in rural areas of Mali receive minimal health care.[20]

Recently, there has been several corporations that have developed in order to attempt to improve Mali's economic and health systems. The most notable of this is the FENASCOM, or the "Fédération Nationale des Associations de Santé Communautaire", which unites several communal associations (around 700 in total) at the national level and strive to sway Malian government's policies on health.[6]

One study has shown that there are key problems regarding Mali's health system.[25] First, the distribution of health care in Mali is poorly managed, resulting in a waste of resources.[25] There are also signs that pharmaceutical policies are lacking in Mali, which contributes to the uneven medical drug distribution among Malian populations.[25]

Sanitation

In 2000, 62–65 percent of the population was estimated to have access to safe drinking water.[8] 69 percent of the population had access to sanitation facilities of some kind. 8 percent were estimated to have access to modern sanitation facilities. 20 percent of the nation’s villages and livestock watering holes had modern water facilities.[8] In urban areas, it was revealed that almost 90% of all citizens had access to improved water.[26]

Little more than a third of Mali had proper sanitation as defined by western standards.[2] Also, the conditions of clean water has not improved much since the percentages in 2000 shown above.[27] This means that 12 million people in Mali do not have access to adequate sanitation and 4 million people do not have access to safe drinking water.[27] Unsafe water drinking and poor sanitation causes over 4,000 children under age 5 to die per year from diarrhea.[27] WaterAid has actively been working in Mali to improve sanitation policies and drinking resources for Malians.[27]

Regarding water development planning, research has shown that it is important to consult the women of Mali, as women are the predominant people gathering and using water.[28] Hydrogeological research under the Peace Corps has shown that local women are the most reliable sources of information regarding water control.[28] A village needed around 50,000 liters of water a day, and it was shown that two electronically powered pumps could provide this much water, while under traditional Malian wells (dug by hand), 64 were needed.[28] Hand-dug wells also had poor quality and unreliable production of water, suggesting that electronic wells could reduce water problems.[28]

Health status

Malaria and other arthropod-borne diseases are prevalent in Mali, as are a number of infectious diseases such as cholera, hepatitis, meningitis, Polio, rabies, malaria, and tuberculosis. Mali’s population also suffers from a high rate of child malnutrition and a low rate of immunization for childhood diseases such as measles and polio.[29]

There were an estimated 100,000 cases of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) in 2010, and an estimated 1.5 percent of the adult population was afflicted with HIV/AIDS in 2007, among the lowest rates in Sub-Saharan Africa (see also HIV/AIDS in Africa).[30]

The 2010 maternal mortality rate per 100,000 births was 830. This compares with 880 in 2005 and 1200 in 1990. The under 5 mortality rate, per 1,000 births was 194 and the neonatal mortality as a percentage of under 5's mortality was 26. In Mali there were 3 midwives per 1,000 live births and the lifetime risk of maternal death was 1 in 22.[31]

Life expectancies

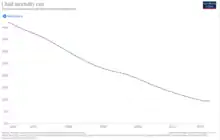

Infant and juvenile mortality rates:[32]

up to 1 year:

80 deaths/1,000 live births. This has decreased significantly over the years, by a percentage of around 50% over the last 20 years.[26]

up to 5 years:115 deaths/1,000 children in 2015 (11.5% percent experience death in their first 5 years).[33] This places Mali at the 8th place in terms of most mortality rates for children under 5.[26] This number has been decreasing steadily, from 132 in 2011, 127 in 2012, 123 in 2013, and 118 in 2014, then 115 currently.[33]

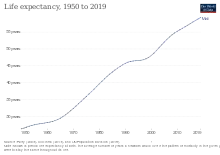

Life expectancy at birth:[30]

total population:

54.55 years (2013 est.)

male:

52.75 years (2013 est.)

female:

56.41 years (2013 est.)

Prevalent diseases

The degree of risk for contracting major infections diseases is very high in Mali.[34] Some of the most common food or waterborne diseases include diarrhea (bacterial and protozoal), hepatitis A, and typhoid fever, all of which pose serious threats to the communities.[34] Malaria and dengue fever is also very common.[34]

HIV/AIDS – adult prevalence rate: 0.9% (2012.)[26]

HIV/AIDS – people living with HIV/AIDS: 100,000 (2012.)[26]

HIV/AIDS – deaths: 5,800 (2007 est.)[30]

Vaccines: Over 89% of Mali's citizens have had basic immunization coverage.[26] However, many children do not receive proper immunization from measles and polio.[29]

Malaria: Among all diseases, malaria is the primary cause of death in Mali, especially for children who are under 5 years old.[35] The prevalence of malaria among children under five years of age was 36% as of 2015.[36] Plasmodium falciparum is the main cause of infection.[36] The entire population of Mali is at risk for malaria, although transmission varies across the country’s five geo-climatic zones.[36] The disease is endemic in the central and southern regions where more than 90 percent of the population lives and epidemic in the north.[36] Internally displaced persons migrating from the north are especially at risk given their low immunity to infection.[36]

Due to the diversity of malaria transmission in Mali, the malaria control strategy emphasizes specific entomological and epidemiological surveillance and universal coverage of key malaria interventions as well as targeted operational research in areas with unstable malaria transmission.[36] There has been significant global funding by organizations like the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), World Health Organization (WHO), and the President's Malaria Initiative.[37] Mali has demonstrated significant progress in scaling up malaria prevention and control interventions, especially in vector control.[36] There was a nearly 50% reduction of under-five mortality rates from 2006 to 2012.[36]

Ebola: See Ebola virus disease in Mali

Since October 2014, when Mali had its first Ebola virus outbreak,[38] there has been a total of eight cases of Ebola with six deaths.[39][40] However, due to the high number of outbreaks in neighboring countries like Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, Mali is ranked as one of the top countries at risk for an outbreak of Ebola.[41]

Rabies: Dog rabies is frequent within Mali, especially the Bamako area (the most hospitalized and urbanized). 17% of people living in Bamako are vaccinated, while others have received no immunization against the rabies. The World Health Organization has set the goal of recommended vaccination coverage to 70%. Door-to-door vaccination and central-point vaccination has been suggested as possible policy implementations.[42]

Epilepsy: Epilepsy affects 15 Malians per 1000. Research has shown that much of Mali's parents with a child afflicted with epilepsy had high levels of misconceptions of the disease. There is a level of stigma directed toward people with epilepsy, and it was shown that most families consulted traditional healers (as opposed to physicians) regarding epilepsy, possibly leading to the misconceptions they have today.[43]

Polio: In June 2011, Mali had its first case with the polio virus (specific strand: WPV, standing for Wild Polio Virus) that caused many problems in the Goundam, Timbuktu region of Mali. However, in September 2015, a new case of polio virus (strand: VDPV, short for Vaccine-derived Polio Virus) has popped up again, resulting in a serious national issue since the probability that polio would spread throughout the country was extremely high (considering the low rates of health care).[44] Polio is a deadly virus that could cause paralysis or even kill, which made the re-emergence of polio virus in Mali a huge threat; in response, the Ministry of Health of Mali and WHO (World Health Organization) has implemented an emergency response to attempt to stop the beginning of an epidemic.[44] Another problem this poses is the fact that this polio was vaccine-derived, in which the disease mutated. This raises to question if any more diseases could mutate from their vaccinated forms to infect people again in Malil.[45]

Nutrition

Because Mali's economy is one of the poorest in the world, regarded as one of the 48 least developed countries by the UN, over half of the country's population survives on less than a dollar every day.[46] Thus, the malnutrition in Mali is severe, especially for children.[47] The malnutrition levels exceed the critical level in the national scope.[47] 18 percent of all children born are born in an underweight or malnourished state.[26] Over 660,000 children are at risk of acute malnutrition, while 18.9 percent of all citizens are underweight in a moderate or severe way.[26][48]

Because of the series of shocks Mali has received recently, including a pastoral crisis in 2010, a drought in 2011, and a political crisis in 2012-2013, there has been reports that 1.5 million people are currently in food insecurity in 2014. This is expected to increase in the "lean season", which is the time between June to October. Because Mali is a landlocked country, and because it is regarded as rank 182 on the UN Human Development Index, Mali is one of the most food deprived countries in the world.[48]

The World Food Programme (WFP) has been supporting the nutritional deprivation of Mali's citizens through two operations: The Emergency Operation (EMOP) and The Country Programme. EMOP provided food and cash to vulnerable families and provided nutritional help for women and children, who do not receive proper food security. EMOP has also implemented free school meals to reduce child hunger. The Country Programme has brought food to school and governmental systems to both encourage education and eliminate hunger. They have also focused efforts in improving aid to pregnant women and breastfeeding women so that they would not be deprived of nutrition.[48]

Children's health

Malaria, a preventable and curable disease that is heavily prevalent in Africa and is detrimental to African children,[49] is prevalent in Mali. Mali's children especially are susceptible not only to malaria but also other diseases and parasites, which prompts their immune systems to generate an unusually high number of responses and mechanisms for defense.[50]

Children in Mali also face severe skin diseases, among which pyoderma tinea capitis, pediculosis capitis, scabies, and molluscum contagiosum are the most prevalent. Many of these skin diseases are associated with poor hygiene. Even though skin diseases cause a severe problem for children in Mali, the public health service does not take care of skin diseases, making skin disease a huge problem in the health of Mali.[51]

Children may be more prone to diseases due to the high rate of child labor, capping at 21.4% of all children in Mali.

Due to the prevalence of child diarrhea in rural Mali, the government of Mali has implemented a "community-led total sanitation" policy that activates communities to create their own toilets. This was implemented to try to stop public defecation. Research has shown that the implementation of this policy in villages promote child growth and improvements in health for children in older children. Research has also shown that monetary support with community-led total sanitation could be the future pathway for Mali to reduce diarrhea and prevent growth faltering.[52]

Children's mental health is also negatively affected by the health conditions in Mali. With around 59,000 children predicted to have lost either one or both of their parents due to disease, there are about as many people having HIV/AIDS in Mali as there are kids without a parent.[2]

The introduction of community health workers in Bamako in 2011 has led to a dramatic reduction in the number deaths of children under five, which have been reduced from 148 per thousand, among the worst in the world, to seven in 2018, about the same as the USA. The free primary healthcare programme for pregnant women and children under five is to be extended across the country.[53]

Women's health

Status of women in Mali

In Mali, women do not receive as many rights in terms of the family laws, as they are vulnerable in cases of divorce, child custody, inheritance rights, and general protection of civil rights. A woman must, for example, pay a large amount of money if she wants a divorce.[54] Although the Malian constitution prohibits discrimination based on gender, domestic violence is common and tolerated against women.[54]

Pregnancy

Women are generally expected to take care of infants and kids for most of their lives.[55] Also, even during pregnancy and times nearing childbirth, women in Mali are culturally pushed to work their normal routines, managing household jobs and taking care of the other kids.[55] Furthermore, breastfeeding is deemed to be the most acceptable way of raising infants, increasing the pressure on women.[55]

Women in Mali have especially high rates of pregnancy at a young age (younger than 18 years of age), even compared to other African countries.[56] 9.8% of girls who are not yet 18 in Mali are mothers, a percentage that is almost 5 times that of Nigeria and Togo. Mali has one of the highest infant mortality rates as well, reaching a peak of 28%, which could be attributed to a lack of ultrasound examinations and tocolysis.[57] Children in Mali also marry very early, which may attribute to the early marriage: 55% of all children marry before the age of 18.[26]

Since 2005, Mali has adopted a free cesarean policy in which all costs associated with the surgery in the public sector are covered.[58]

Health in urban Mali

Despite the very low number of physicians in Mali (8 physicians per 100,000 people[3]), study has shown that most women in Mali seek medical treatment when giving birth.[56] This was especially prevalent in the urban regions of Mali. Also, a woman's social indicators, including her status and type of marriage (widowed, married, or engaged in a male polygyny), her social power regarding other members of the community, and her connections throughout different regions and a variety of people were the defining characteristics of her status of health as well.[56]

There is a strong correlation between a woman's social status and health status, as women of more esteemed social status sought more medical treatment and care than those of lesser status who tried to fight through illnesses themselves.[56] Two of the most affected groups in terms of social instability (and therefore health insecurity) were those pregnant with polygamous men and those who have lost their husbands, directing many researchers to target those women in terms of aid.[56]

Because of the nature of Mali's cultural context among women, their relations with other women (including social networks, conflicts among co-wives, standings in women's associations) heavily influences their use of contraceptives, number of children, and child survival.[56] While many women in Mali suffer from sexually transmitted infections, this area is quite understudied and is lacking in data.[56]

Health in rural Mali

There is a severe dearth of health services in rural Mali, since even urban regions do not have adequate numbers of physicians. Unlike women living in urban Mali, women in rural regions tended to depend more on other around them for their health needs, being influenced by their community and the number of people with at least secondary education. Delivery (of infants, from pregnancy) remains a huge issue for those living in rural areas. Poverty and personal problems related to rural areas also negatively affect the health status of women in these areas.[59]

One study that investigated rural villages in Mali revealed that in these areas, women and families had to decide between cost and efficiency of medical care because they were too far from medical centers.[60] What was also found was that qualified staff members in medicine worked few hours and often turned down clients, forcing those in rural Mali to depend on traditional medicinal healing.[60] Also, even though the per capita income was less than $200 in the rural villages, medicines cost more than they are in Western countries.[60]

Female genital cutting practices

Female genital mutilation is an act that intentionally harms or damages the female organs in a nonmedical setting.[61] More than 125 million young girls from birth to age 15 undergo this process, of which most are from Africa and Middle East.[61] Although the U.N. and World Health Organization has implemented policies to stop the inhumane act of removing genital parts, the cutting is often culturally and religiously rooted in societies, making it hard to eliminate.[61]

Mali, like many other African countries, engage in female genital cutting practices, which negatively impact women's health.[62] Female genital cutting often occurs between the ages of 4 to 8, and results in hemorrhage, shock, pain, damage to organs, urinary infections, and other serious diseases.[62] Because the equipment used may not be cleaned completely, HIV and Hepatitis B is also spread with the procedure. In Mali, around 94 percent of women undergo female genital cutting practices. Apart from physical health, this is also commonly seen as having a severe psychological effect on women as well.[62] Approximately 95 percent of adult women have undergone female genital mutilation.[54]

The objective of the female genital cutting practice is to decrease promiscuity for the husband once the woman gets married. It is often seen as a religious and cultural tradition, even though the government in Mali has made several attempts to alleviate the practices.[62]

See also

References

- "World Health Organization" (PDF). WHO World Health Statistics 2015. World Health Organization. 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- "Poverty & Healthcare". Our Africa. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- "The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. CIA. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- "Mali clashes force 120 000 from homes". News24. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- Lim, Stephen; et, al. "Measuring human capital: a systematic analysis of 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016". Lancet. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "Improving Mali's Health Care System". www.ceci.ca. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- "Human Development Data (1990-2017)". United Nations Human Development Programme. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- Mali country profile. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (January 2005). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "A spatial database of health facilities managed by the public health sector in sub-Saharan Africa". World Health Organization. February 11, 2019. Archived from the original on April 22, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- French: Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire or CHU

- "Hospitals in Mali". London Daily News. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- "Local Medical Care Physicians list for Bamako, Mali" (PDF). US Embassy, Bamako. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- "List of medical facilities/practitioners in Mali" (PDF). British Embassy, Bamako. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- "Golden Life Hospital". Golden Life American Hospital. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- "Kayes Hospital". USAID. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- "Sikasso Hospital". USAID. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- "The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-04-26. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- "Mali". MSF USA. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- Malian leader lays foundation stone for 150-bed hospital Archived 2009-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. PANA Press. 2009-04-11.

- "Mali's Health System". International Insulin Foundation. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- "Mali". www.healthpolicyproject.com. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- Allegranzi, Benedetta; Sax, Hugo; Bengaly, Loséni; Riebet, Hervé; Minta, Daouda K.; Chraiti, Marie-Noelle; Sokona, Fatoumata Maiga; Gayet-Ageron, Angele; Bonnabry, Pascal (2010-02-01). "Successful Implementation of the World Health Organization Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy in a Referral Hospital in Mali, Africa". Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 31 (2): 133–141. doi:10.1086/649823. ISSN 1559-6834.

- Johnson, Ari, Goss, Adeline, Beckerman, Jessica, and Castro, Arachu. "Hidden costs: The direct and indirect impact of user fees on access to malaria treatment and primary care in Mali." Social Science & Medicine 75.10 (2012) 1786-1792.

- "Bamako, 1997 to 2012: What's changed?". Bridges from Bamako. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- Coulibaly, S. O.; Keita, M. (1996-12-01). "[Economics of health care in Mali]". Santé (Montrouge, France). 6 (6): 353–359. ISSN 1157-5999. PMID 9053102.

- "Statistics". UNICEF. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

- "Mali - Where We Work - WaterAid America". www.wateraid.org. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- Shonsey, Cara; Gierke, John (2013-12-01). "Quantifying available water supply in rural Mali based on data collected by and from women". Journal of Cleaner Production. Special Volume: Water, Women, Waste, Wisdom and Wealth. 60: 43–52. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.02.013.

- "Polio resurfaces in Mali and Ukraine". sciencemag.org. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- "CIA The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency, USA. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- "The State of World's Midwifery 2011: Mali" (PDF). United Nations Population Fund. 2011. Retrieved 1 Aug 2011..

- Samaké, Salif; Traoré, Seydou Moussa; Ba, Souleymane; Dembélé, Étienne; Diop, Mamadou; Mariko, Soumaïla; Libité, Paul Roger (2007). Mali: Enquête Démographique et de Santé (EDSM-IV) 2006 (PDF). Calverton, MD, USA: Demographic and Health Surveys. p. 185 Table 12.1..

- "Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1,000 live births) / Data / Table". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

- "Mali Major infectious diseases - Demographics". www.indexmundi.com. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- "Mali". www.pmi.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- "Mali" (PDF). President's Malaria Initiative. 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "World Malaria Report 2014". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- "Ebola Response Roadmap Situation Report Update" (PDF). World Health organization. 25 October 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- "Mali announces end of its Ebola outbreak". The Washington Times. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- "Mali ends last quarantines, could be Ebola-free next month" (PDF). Reuters. 16 December 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- Rihouay, Francois. "Mali Red Cross Says Ebola Tracking Hampered by Health System". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- Muthiani, Yvonne; Traoré, Abdallah; Mauti, Stephanie; Zinsstag, Jakob; Hattendorf, Jan (2015-06-15). "Low coverage of central point vaccination against dog rabies in Bamako, Mali". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 120 (2): 203–209. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.04.007. PMID 25953653.

- Pickering, Amy J, Djebbari, Habiba, Lopez, Carolina, Massa, Coulibaly, Alzua, Maria Laura. " Effect of a community-led sanitation intervention on child diarrhoea and child growth in rural Mali: a cluster-randomised controlled trial". The Lancet Global Health 3.11 (2015) e701-e711. Electronic.

- "Polio outbreak confirmed in Mali". www.afro.who.int. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- "Polio Case Detected in Mali, Country on 'High Alert': WHO". NDTV.com. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- "Economy & Industry". Our Africa. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- "Mali / Hunger Relief in Africa / Action Against Hunger". www.actionagainsthunger.org. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- "Mali / WFP / United Nations World Food Programme - Fighting Hunger Worldwide". www.wfp.org. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- "WHO / Malaria". www.who.int. Retrieved 2015-10-09.

- Thomas, Bolaji N. et al. "Circulating Immune Complex Levels Are Associated with Disease Severity and Seasonality in Children with Malaria from Mali."Biomarker Insights 7 (2012): 81–86. PMC. Web. 25 Sept. 2015.

- Mahe, Antoine, Prual, Alain, Konate, Madina, Bobin, Pierre. "Skin diseases of children in Mali: A public health problem." Tropical Medicine & Hygiene 89.5 (1995) 467-470. Print.

- Pickinerg, Amy J., Djebbari, Habiba, Carolina, Lopez, Coulibaly, Massa, Alzua, Maria Laura. "Effect of a community-led sanitation intervention on child diarrhoea and child growth in rural Mali: a cluster-randomised controlled trial". The Lancet Global Health 3.11 (2015). e701-e711, Print.

- Pilling, David (27 February 2019). "Mali's 'astounding' community health programme should be emulated". Financial Times. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- "Mali". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- Dettwyler Katherine A (1987). "Breastfeeding and weaning in Mali: Cultural context and hard data". Social Science & Medicine. 24 (8): 633–644. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(87)90306-6. PMID 3603085.

- Bove Riley M; Vala-Haynes Emily; Valeggia Claudia R (2012). "Women's health in urban Mali: Social predictors and health itineraries". Social Science & Medicine. 75 (8): 1392–1399. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.012. PMC 3560408. PMID 22818488.

- Kunzel W.; Herrero J.; Onwuhafua P.; Staub T.; Hornung C. (1996). "Maternal and perinatal health in Mali, Togo and Nigeria". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 69 (1): 11–17. doi:10.1016/0301-2115(95)02528-6. PMID 8909951.

- Witter, S., Boukhalfa, C.; et al. (2016). "Cost and impact of policies to remove and reduce fees for obstetric care in Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali and Morocco". International Journal for Equity in Health. 15 (123): 123. doi:10.1186/s12939-016-0412-y. PMC 4970227. PMID 27483993.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gage Anastasia J (2007). "Barriers to the utilization of maternal health care in rural Mali". Social Science & Medicine. 65 (8): 1666–1682. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.001. PMID 17643685.

- "Client choice of health care treatment in rural Mali. POPLINE.org". www.popline.org. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- "WHO / Female genital mutilation". www.who.int. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- Jones, Heidi, Diop, Nafissatou, Askew, Ian, and Kabore, Inoussa. "Female Genital Cutting Practices in Burkina Faso and Mali and Their Negative Health Outcomes." Studies in Family Planning 30.3 (1999) 219-230.