hh blood group

hh,[1] or the Bombay blood group, is a rare blood type. This blood phenotype was first discovered in Bombay by Dr. Y. M. Bhende in 1952. It is mostly found in the Indian sub-continent (India, Bangladesh, Pakistan) and parts of the Middle East such as Iran.

Problems with blood transfusion

The first person found to have the Bombay phenotype had a blood type that reacted to other blood types in a way never seen before. The serum contained antibodies that attacked all red blood cells of normal ABO phenotypes. The red blood cells appeared to lack all of the ABO blood group antigens and to have an additional antigen that was previously unknown.

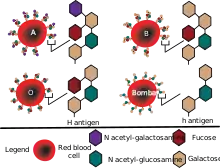

Individuals with the rare Bombay phenotype (hh) do not express H antigen (also called substance H), the antigen which is present in blood group O. As a result, they cannot make A antigen (also called substance A) or B antigen (substance B) on their red blood cells, whatever alleles they may have of the A and B blood-group genes, because A antigen and B antigen are made from H antigen. For this reason people who have Bombay phenotype can donate red blood cells to any member of the ABO blood group system (unless some other blood factor gene, such as Rh, is incompatible), but they cannot receive blood from any member of the ABO blood group system (which always contains one or more of A, B or H antigens), but only from other people who have Bombay phenotype.

Receiving blood that contains an antigen which has never been in the patient's own blood causes an immune reaction due to the immune system of a hypothetical receiver producing immunoglobulins against that antigen—in the case of a Bombay patient, not only against antigens A and B, but also against H antigen.

In order to avoid complications during a blood transfusion, it is very important to detect Bombay phenotype individuals, but the usual tests for ABO blood group system would show them as group O. Since anti-H immunoglobulins can activate the complement cascade, it will lead to the lysis of red blood cells while they are still in the circulation, provoking an acute hemolytic transfusion reaction. This, of course, cannot be prevented unless those typing the blood and providing care are aware of the existence of the Bombay blood group and have the means to test for it.

Incidence

This very rare phenotype is generally present in about 0.0004% (about 4 per million) of the human population, though in some places such as Mumbai (formerly Bombay) locals can have occurrences in as much as 0.01% (1 in 10,000) of inhabitants. Given that this condition is very rare, any person with this blood group who needs an urgent blood transfusion will probably be unable to get it, as no blood bank would have any in stock. Those anticipating the need for blood transfusion may bank blood for their own use; of course, this option is not available in cases of accidental injury. For example, by 2017 only one Colombian person was known to have this phenotype, and blood had to be imported from Brazil for a transfusion.[2]

Biochemistry

Biosynthesis of the H, A and B antigens involves a series of enzymes (glycosyl transferases) that transfer monosaccharides. The resulting antigens are oligosaccharide chains, which are attached to lipids and proteins that are anchored in the red blood cell membrane. The function of the H antigen, apart from being an intermediate substrate in the synthesis of ABO blood group antigens, is not known, although it may be involved in cell adhesion. People who lack the H antigen do not suffer from deleterious effects, and being H-deficient is only an issue if they need a blood transfusion, because they would need blood without the H antigen present on red blood cells.

The specificity of the H antigen is determined by the sequence of oligosaccharides. More specifically, the minimum requirement for H antigenicity is the terminal disaccharide fucose-galactose, where the fucose has an alpha(1-2)linkage. This antigen is produced by a specific fucosyl transferase (Galactoside 2-alpha-L-fucosyltransferase 2) that catalyzes the final step in the synthesis of the molecule. Depending upon a person's ABO blood type, the H antigen is converted into either the A antigen, B antigen, or both. If a person has group O blood, the H antigen remains unmodified. Therefore, the H antigen is present more in blood type O and less in blood type AB.

Two regions of the genome encode two enzymes with very similar substrate specificities: the H locus (FUT1) which encodes the Fucosyl transferase and the Se locus (FUT2) that instead indirectly encodes a soluble form of the H antigen, which is found in bodily secretions. Both genes are on chromosome 19 at q.13.3. — FUT1 and FUT2 are tightly linked, being only 35 kb apart. Because they are highly homologous, they are likely to have been the result of a gene duplication of a common gene ancestor.

The H locus contains four exons that span more than 8 kb of genomic DNA. Both the Bombay and para-Bombay phenotypes are the result of point mutations in the FUT1 gene. At least one functioning copy of FUT1 needs to be present (H/H or H/h) for the H antigen to be produced on red blood cells. If both copies of FUT1 are inactive (h/h), the Bombay phenotype results. The classical Bombay phenotype is caused by a Tyr316Ter mutation in the coding region of FUT1. The mutation introduces a stop codon, leading to a truncated enzyme that lacks 50 amino acids at the C-terminal end, rendering the enzyme inactive. In Caucasians, the Bombay phenotype may be caused by a number of mutations. Likewise, a number of mutations have been reported to underlie the para-Bombay phenotype. The Se locus contains the FUT2 gene, which is expressed in secretory glands. Individuals who are "secretors" (Se/Se or Se/se) contain at least one copy of a functioning enzyme. They produce a soluble form of H antigen that is found in saliva and other bodily fluids. "Non-secretors" (se/se) do not produce soluble H antigen. The enzyme encoded by FUT2 is also involved in the synthesis of antigens of the Lewis blood group.

Genetics

Bombay phenotype occurs in individuals who have inherited two recessive alleles of the H gene (i.e.: their genotype is hh). These individuals do not produce the H carbohydrate that is the precursor to the A and B antigens, meaning that individuals may possess alleles for either or both of the A and B alleles without being able to express them. Because both parents must carry this recessive allele to transmit this blood type to their children, the condition mainly occurs in small closed-off communities where there is a good chance of both parents of a child either being of Bombay type, or being heterozygous for the h allele and so carrying the Bombay characteristic as recessive. Other examples may include noble families, which are inbred due to custom rather than local genetic variety.

Hemolytic disease of the newborn

In theory, the maternal production of anti-H during pregnancy might cause hemolytic disease in a fetus who did not inherit the mother's Bombay phenotype. In practice, cases of HDN caused in this way have not been described. This may be possible due to the rarity of the Bombay phenotype but also because of the IgM produced by the immune system of the mother. Since IgMs are not transported across the microscopic placental blood vessels (like IgG are) they cannot reach the blood stream of the fetus to provoke the expected acute hemolytic reaction.

References

- Dean L. (2005). "6: The Hh blood group". Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information (US) ll. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- Colprensa (2017-07-13). "La primera importación de sangre salvó a una niña paisa" [The first import of blood saved a paisa girl]. El Colombiano (in Spanish). Medellín. Retrieved 2017-07-13.

External links

- Hh at BGMUT Blood Group Antigen Gene Mutation Database at NCBI, NIH

- RMIT University The Bombay, para-Bombay and other H deficiencies

- BombayBloodGroup.Org an initiative to connect individuals who donate and who are in need of Bombay blood group.

- Genetics of the Bombay Phenotype

- know more