History of syphilis

The first recorded outbreak of syphilis in Europe occurred in 1494/1495 in Naples, Italy, during a French invasion.[1][2] Because it was spread by returning French troops, the disease was known as "French disease", and it was not until 1530 that the term "syphilis" was first applied by the Italian physician and poet Girolamo Fracastoro.[2] The causative organism, Treponema pallidum, was first identified by Fritz Schaudinn and Erich Hoffmann in 1905.[2] The first effective treatment, Salvarsan, was developed in 1910 by Sahachirō Hata in the laboratory of Paul Ehrlich. It was followed by the introduction of penicillin in 1943.[2]

Many well-known figures, including Scott Joplin, Franz Schubert, Friedrich Nietzsche, Al Capone, and Édouard Manet are believed to have contracted the disease.[2]

Origin

The history of syphilis has been well studied, but the exact origin of the disease remains unknown.[3] There are two primary hypotheses: one proposes that syphilis was carried to Europe from the Americas by the crew(s) of Christopher Columbus as a byproduct of the Columbian exchange, while the other proposes that syphilis previously existed in Europe but went unrecognized.[1] These are referred to as the "Columbian" and "pre-Columbian" hypotheses, respectively.[1]

Syphilis is the first "new" disease to be discovered after the invention of printing. News of it spread quickly and widely, and documentation is abundant. For the time, it was "front page news" that was widely known among the literate. It is also the first disease to be widely recognized as a sexually transmitted disease, and it was taken as indicative of the moral state (sexual behavior) of the peoples in which it was found. Its geographic origin and moral significance were debated as had never been the case with any other illness. European countries blamed it on each other. Somewhat later, when the significance of the Western Hemisphere was perceived, it has been used in both pro- and anti-colonial discourse.

Columbian theory

This common theory[4] holds that syphilis was a New World disease brought back by Columbus, Martín Alonso Pinzón, and/or other members of their crews as an unintentional part of the Columbian Exchange. Columbus's first voyages to the Americas occurred three years before the Naples syphilis outbreak of 1495.[1] As Naples fell before the invading army of Charles the VIII in 1495, a plague broke out among the French leader's troops. When the army disbanded shortly after the campaign, the troops, composed largely of mercenaries, returned to their homes and disseminated the disease across Europe.[5] 536 skeletal remains in the Dominican Republic have shown evidence characteristic of treponemal disease in 6–14% of the afflicted population, which Rothschild and colleagues have postulated was syphilis.[6] The Aztec god Nanahuatzin is often interpreted as suffering from syphilis.[7]

The 2011 Yearbook of Physical Anthropology published an appraisal by Harper and colleagues, of previous studies and stated that the "skeletal data bolsters the case that syphilis did not exist in Europe before Columbus set sail."[8] The scientific evidence as determined by a systematic review of 54 previously published, peer-reviewed instances lends support to the theory that syphilis was unknown in Europe until Columbus returned from the Americas. According to this appraisal, "Skeletal evidence that reputedly showed signs of syphilis in Europe and other parts of the Old World before Christopher Columbus made his voyage in 1492 does not hold up when subjected to standardized analyses for diagnosis and dating, according to an appraisal in the current Yearbook of Physical Anthropology. This is the first time that all 54 previously published cases have been evaluated systematically, and bolsters the case that syphilis came from the New World."[9] In an article criticizing the presentation of new research findings in PBS and BBC documentaries about syphilis, researchers said they showed "a blatant disregard for the peer review process in making the case for pre-Columbian syphilis in the Old World. [...] As in all scientific fields, in order to resolve the controversy over the origin and antiquity of syphilis in the Old World, there is a strong need for adherence to standard practice in scientific publication and the increased publication of relevant evidence in peer-reviewed journals."[10]

Pre-Columbian theory

The theory holds that syphilis was present in Europe before the arrival of Europeans in the Americas. Some scholars during the 18th and 19th centuries believed that the symptoms of syphilis in its tertiary form were described by Hippocrates in Classical Greece.[11] Skeletons in pre-Columbus Pompeii and Metaponto in Italy with damage similar to that caused by congenital syphilis have also been found.[12][13][14] Douglas W. Owsley, a physical anthropologist at the Smithsonian Institution, and other supporters of this idea, say that many medieval European cases of leprosy, colloquially called lepra, were actually cases of syphilis. However, these claims have not been submitted for peer review, and the evidence that has been made available to other scientists is weak.[10] Although folklore claimed that syphilis was unknown in Europe until the return of the diseased sailors of the Columbian voyages, Owsley says that "syphilis probably cannot be 'blamed'—as it often is—on any geographical area or specific race. The evidence suggests that the disease existed in both hemispheres from prehistoric times. It is only coincidental with the Columbus expeditions that the syphilis previously thought of as 'lepra' flared into virulence at the end of the 15th century."[15] Lobdell and Owsley wrote that a European writer who recorded an outbreak of "lepra" in 1303 was "clearly describing syphilis."[15] In 2015, researchers discovered 14th-century skeletons in Austria that they say show signs of congenital syphilis, which is transmitted from mother to child rather than sexually.[16] In 2020 DNA analysis of nine infected skeletons was advanced to defend the "pre-Columbian" hypotheses, but is short of conclusive.[17]

Combination theory

Historian Alfred Crosby suggested in 2003 that both theories are partly correct in a "combination theory". Crosby says that the bacterium that causes syphilis belongs to the same phylogenetic family as the bacteria that cause yaws and several other diseases. Despite the tradition of assigning the homeland of yaws to sub-Saharan Africa, Crosby notes that there is no unequivocal evidence of any related disease having been present in pre-Columbian Europe, Africa, or Asia. Crosby writes, "It is not impossible that the organisms causing treponematosis arrived from America in the 1490s ... and evolved into both venereal and non-venereal syphilis and yaws."[18] However, Crosby considers it more likely that a highly contagious ancestral species of the bacteria moved with early human ancestors across the land bridge of the Bering Straits many thousands of years ago without dying out in the original source population. He hypothesizes that "the differing ecological conditions produced different types of treponematosis and, in time, closely related but different diseases."[18] A more recent, modified version of the Columbian theory that better fits skeletal evidence from the New World, and also "absolved the New World of being the birthplace of syphilis", proposes that a nonvenereal form of treponemal disease, without the lesions common to congenital syphilis, was brought back to Europe by Columbus and his crew. Upon arrival in the Old World, the bacterium, which was similar to modern day yaws, responded to new selective pressures with the eventual birth of the subspecies of sexually transmitted syphilis.[10] This theory is supported by genetic studies of venereal syphilis and related bacteria, which found a disease intermediate between yaws and syphilis in Guyana, South America.[19][20] However, the study has been criticized in part because some of its conclusions were based on a tiny number of sequence differences between the Guyana strains and other treponemes whose sequences were examined.[10][21]

European outbreak

The first well-recorded European outbreak of what is now known as syphilis occurred in 1495 among French troops besieging Naples, Italy.[1][22] It may have been transmitted to the French via Spanish mercenaries serving King Charles of France in that siege.[15] From this centre, the disease swept across Europe. As Jared Diamond describes it, "[W]hen syphilis was first definitely recorded in Europe in 1495, its pustules often covered the body from the head to the knees, caused flesh to fall from people's faces, and led to death within a few months." The disease then was much more lethal than it is today.[23] The epidemiology of this first syphilis epidemic shows that the disease was either new or a mutated form of an earlier disease.

Some researchers argue that syphilis was carried from the New World to Europe after Columbus' voyages, while others argue the disease has a much longer history in Europe. Many of the crew members who served on this voyage later joined the army of King Charles VIII in his invasion of Italy in 1495, which some argue may have resulted in the spreading of the disease across Europe and as many as five million deaths.[20] Some findings suggest Europeans could have carried the nonvenereal tropical bacteria home, where the organisms may have mutated into a more deadly form in the different conditions and low immunity of the population of Europe.[24] Syphilis was a major killer in Europe during the Renaissance.[25] In his Serpentine Malady (Seville, 1539) Ruy Díaz de Isla estimated that over a million people were infected in Europe. He also postulated that the disease was previously unknown, and came from the island of Hispaniola (modern Dominican Republic and Haiti).[26]

According to a 2020 study, more than 20% of individuals in the range of 15–34 years old in late 18th century London were treated for syphilis.[27]

Historical terms

The name "syphilis" was coined by the Italian physician and poet Girolamo Fracastoro in his pastoral noted poem, written in Latin, titled Syphilis sive morbus gallicus (Latin for "Syphilis or The French Disease") in 1530.[2][28] The protagonist of the poem is a shepherd named Syphilus (perhaps a variant spelling of Sipylus, a character in Ovid's Metamorphoses). Syphilus is presented as the first man to contract the disease, sent by the god Apollo as punishment for the defiance that Syphilus and his followers had shown him.[2] From this character Fracastoro derived a new name for the disease, which he also used in his medical text De Contagione et Contagiosis Morbis (1546) ("On Contagion and Contagious Diseases").[29]

Until that time, as Fracastoro notes, syphilis had been called the "French disease" (Italian: mal francese) in Italy, Malta,[30] Poland and Germany, and the "Italian disease" in France. In addition, the Dutch called it the "Spanish disease", the Russians called it the "Polish disease", and the Turks called it the "Christian disease" or "Frank (Western European) disease" (frengi). These "national" names were generally reflective of contemporary political spite between nations and frequently served as a sort of propaganda; the Protestant Dutch, for example, fought and eventually won a war of independence against their Spanish Habsburg rulers who were Catholic, so referring to Syphilis as the "Spanish" disease reinforced a politically useful perception that the Spanish were immoral or unworthy. However, the attributions are also suggestive of possible routes of the spread of the infection, at least as perceived by "recipient" populations. The inherent xenophobia of the terms also stemmed from the disease's particular epidemiology, often being spread by foreign sailors and soldiers during their frequent sexual contact with local prostitutes.[31]

During the 16th century, it was called "great pox" in order to distinguish it from smallpox. In its early stages, the great pox produced a rash similar to smallpox (also known as variola). However, the name is misleading, as smallpox was a far more deadly disease. The terms "lues"[32] (or Lues venerea, Latin for "venereal plague") and "Cupid's disease"[33] have also been used to refer to syphilis. In Scotland, syphilis was referred to as the Grandgore or Spanyie Pockis.[34] The ulcers suffered by British soldiers in Portugal were termed "The Black Lion".[35]

Historical treatments

.jpg.webp)

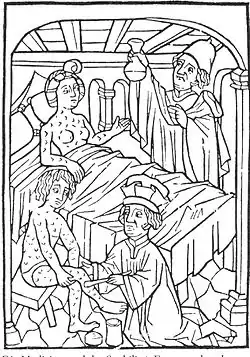

There were originally no effective treatments for syphilis, although a number of remedies were tried. In the infant stages of this disease in Europe, many ineffective and dangerous treatments were used. The aim of treatment was to expel the foreign, disease-causing substance from the body, so methods included blood-letting, laxative use, and baths in wine and herbs or olive oil.[36]

Mercury was a common, long-standing treatment for syphilis.[37] The Canon of Medicine (1025) by the Persian physician Ibn Sina suggested treating early stages of leprosy with mercury; during an early European outbreak of the disease, Francisco Lopez de Villalobos compared this to syphilis, though he noted major differences between the diseases.[38] Paracelsus likewise noted mercury's positive effects in the Arabic treatment of leprosy, which was thought to be related to syphilis, and used the substance for treating the disease.[39] Giorgio Sommariva of Verona is recorded to have used mercury to treat syphilis in 1496, and is often recognized as the first physician to have done so, although he may not have been a physician.[40] During the sixteenth century, mercury was administered to syphilitic patients in various ways, including by rubbing it on the skin, by applying a plaster, and by mouth.[41] A "Fumigation" method of administering mercury was also used, in which mercury was vaporized over a fire and the patients were exposed to the resulting steam, either by being placed in a bottomless seat over the hot coals, or by having their entire bodies except for the head enclosed in a box (called a "tabernacle") that received the steam.[41] The goal of mercury treatment was to cause the patient to salivate, which was thought to expel the disease. Unpleasant side effects of mercury treatment included gum ulcers and loose teeth.[41] Mercury continued to be used in syphilis treatment for centuries; an 1869 article by Thomas James Walker, M. D., discussed administering mercury by injection for this purpose.[42]

Guaiacum was a popular treatment in the sixteenth century and was strongly advocated by Ulrich von Hutten and others.[41] Because guaiacum came from Hispaniola where Columbus had landed, proponents of the Columbian theory contended that God had provided a cure in the same location from which the disease originated.[41] In 1525, the Spanish priest Francisco Delicado, who himself suffered from syphilis, wrote El modo de adoperare el legno de India occidentale (How to Use the Wood from the West Indies[43]) discussing the use of guaiacum for treatment of syphilis.[44] Although guaiacum did not have the unpleasant side effects of mercury, guaiacum was not particularly effective,[41] at least not beyond the short term,[44] and mercury was thought to be more effective.[41] Some physicians continued to use both mercury and guaiacum on patients. After 1522, the Blatterhaus—an Augsburg municipal hospital for the syphilitic poor[45]—would administer guaiacum (as a hot drink, followed by a sweating cure) as the first treatment, and use mercury as the treatment of last resort.[41]

Another sixteenth-century treatment advocated by the Italian physician Antonio Musa Brassavola was the oral administration of Root of China,[41] a form of sarsaparilla (Smilax).[46] In the seventeenth century, English physician and herbalist Nicholas Culpeper recommended the use of heartsease (wild pansy).[47]

Before effective treatments were available, syphilis could sometimes be disfiguring in the long term, leading to defects of the face and nose ("nasal collapse"). Syphilis was a stigmatized disease due to its sexually transmissible nature. Such defects marked the person as a social pariah, and a symbol of sexual deviancy. Artificial noses were sometimes used to improve this appearance. The pioneering work of the facial surgeon Gasparo Tagliacozzi in the 16th century marked one of the earliest attempts to surgically reconstruct nose defects. Before the invention of the free flap, only local tissue adjacent to the defect could be harvested for use, as the blood supply was a vital determining factor in the survival of the flap. Tagliacozzi's technique was to harvest tissue from the arm without removing its pedicle from the blood supply on the arm. The patient would have to stay with their arm strapped to their face until new blood vessels grew at the recipient site, and the flap could finally be separated from the arm during a second procedure.

As the disease became better understood, more effective treatments were found. An antimicrobial used for treating disease was the organo-arsenical drug Salvarsan, developed in 1908 by Sahachiro Hata in the laboratory of Nobel prize winner Paul Ehrlich. This group later discovered the related arsenic, Neosalvarsan, which is less toxic.[48]

It was observed that sometimes patients who developed high fevers were cured of syphilis. Thus, for a brief time malaria was used as treatment for tertiary syphilis because it produced prolonged and high fevers (a form of pyrotherapy). This was considered an acceptable risk because the malaria could later be treated with quinine, which was available at that time. Malaria as a treatment for syphilis was usually reserved for late disease, especially neurosyphilis, and then followed by either Salvarsan or Neosalvarsan as adjuvant therapy. This discovery was championed by Julius Wagner-Jauregg,[49] who won the 1927 Nobel Prize for Medicine for his discovery of the therapeutic value of malaria inoculation in the treatment of neurosyphilis. Later, hyperthermal cabinets (sweat-boxes) were used for the same purpose.[50] These treatments were finally rendered obsolete by the discovery of penicillin, and its widespread manufacture after World War II allowed syphilis to be effectively and reliably cured.[51]

History of diagnosis

In 1905, Schaudinn and Hoffmann discovered Treponema pallidum in tissue of patients with syphilis.[2] One year later, the first effective test for syphilis, the Wassermann test, was developed. Although it had some false positive results, it was a major advance in the detection and prevention of syphilis. By allowing testing before the acute symptoms of the disease had developed, this test allowed the prevention of transmission of syphilis to others, even though it did not provide a cure for those infected. In the 1930s the Hinton test, developed by William Augustus Hinton, and based on flocculation, was shown to have fewer false positive reactions than the Wassermann test.[52] Both of these early tests have been superseded by newer analytical methods.

While working at the Rockefeller University (then called the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research) in 1913, Hideyo Noguchi, a Japanese scientist, demonstrated the presence of the spirochete Treponema pallidum in the brain of a progressive paralysis patient, associating Treponema pallidum with neurosyphilis.[53] Prior to Noguchi's discovery, syphilis had been a burden to humanity in many lands. Without its cause being understood, it was sometimes misdiagnosed and often misattributed to damage by political enemies. It is called "the great pretender" for its variety of symptoms. Felix Milgrom developed a test for syphilis. The Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize was named to honor the man who identified the agent in association with the late form of the infectious disease.[54]

Prevalence

An excavation of a seventeenth-century cemetery at St Thomas's Hospital in London, England found that 13 per cent of skeletons showed evidence of treponemal lesions. These lesions are only present in a small minority of syphilitic cases, implying that the hospital was treating large numbers of syphilitics. In 1770s London, approximately 1 in 5 people over the age of 35 were infected with syphilis. In 1770s Chester, the figure was about 8.06 per cent. By 1911, the figure for London was 11.4 per cent, about half that of the 1770s.[55][56]

A 2014 study estimated the prevalance of syphilis in the United Kingdom in 1911-1912 as 7.771%. The location with the highest prevalence was London, at 11.373%, and the social class with the highest prevalence was unskilled working-class, at 11.781%.[57]

The control of syphilis in the United Kingdom began with the 1916 report of a Royal Commission on Venereal Diseases. Clinics were established offering testing and education. This caused a fall in the prevalence of syphilis, leading to almost a halving of tabes dorsalis between 1914 and 1936. With the mass production of penicillin from 1943, syphilis could be cured. Syphilis screening was introduced for every pregnancy. Contact tracing was also introduced.[58] By 1956, congenital syphilis had been almost eliminated, and female cases of acquired syphilis had been reduced to a hundredth of their level just 10 years previously.[59]

In 1978 in England and Wales, homosexual men accounted for 58% of syphilis cases in (and 76% of cases in London), but by 1994–6 this figure was 25%, possibly driven by safe-sex practices to avoid HIV. In 1995, only 130 total cases were reported. A substantial proportion of infections are linked to foreign travel. Antenatal testing continues.[58]

In the United States in 1917, 6% of World War I servicemen were found to have syphilis. In 1936 a public health campaign began to prescribe arsphenamine to treat syphilis. Between 1945 and 1955 penicillin was used to treat over two million Americans for syphilis, and contact tracing was introduced. Syphilis prevalance dropped to an all time low by 1955. A total of 6993 cases of primary and secondary syphilis were recorded in 1998, the lowest number since 1941.[58] In 2000 and 2001 in the United States, the national rate of reported primary and secondary syphilis cases was 2.1 cases per 100,000 population (6103 cases reported). This was the lowest rate since 1941. As of 2014, the incidence increased to 6.3 cases per 100,000 population (19,999 cases reported). The majority of these new cases were in men who have sex with men. Syphilis in newborns in the United States increased from 8.4 cases per 100,000 live births (334 cases) between 2008 and 2012 to 11.6 cases per 100,000 live births (448 cases) between 2012 and 2014.[60]

Arts and literature

The earliest known depiction of an individual with syphilis is Albrecht Dürer's Syphilitic Man, a woodcut believed to represent a Landsknecht, a Northern European mercenary.[62] The myth of the femme fatale or "poison women" of the 19th century is believed to be partly derived from the devastation of syphilis, with classic examples in literature including John Keats' La Belle Dame sans Merci.[63][64] Poet Sebastian Brandt in 1496 wrote a poem titled De pestilentiali Scorra sive mala de Franzos which explains the spread of the disease across the European continent.[65] Brandt also created artistic creations showing religious and political views of syphilis, especially with a work showing Saint Mary and Jesus throwing lightning to punish or cure those afflicted by syphilis, and he also added King Maximilian I in the work, being rewarded by Mary and Jesus for his work against the immoral disease, to show the strong relationship between church and state during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[66]

The Flemish artist Stradanus designed a print of a wealthy man receiving treatment for syphilis with the tropical wood guaiacum sometime around 1580.[67] The title of the work is "Preparation and Use of Guayaco for Treating Syphilis". That the artist chose to include this image in a series of works celebrating the New World indicates how important a treatment, however ineffective, for syphilis was to the European elite at that time. The richly colored and detailed work depicts four servants preparing the concoction while a physician looks on, hiding something behind his back while the hapless patient drinks.[68] Another artistic depiction of syphilis treatment is credited to Jacques Laniet in the seventeenth century as he illustrated a man using the fumigation stove, another popular method of syphilis treatment, with a nearby barrel etched with the saying "For a pleasure, a thousand pains."[66] Remedies to cure syphilis were frequently illustrated to deter those from acts which could lead to the contraction of syphilis because the treatment methods were normally painful and ineffective.

Tuskegee and Guatemala studies

One of the most infamous United States cases of questionable medical ethics in the 20th century was the Tuskegee syphilis study.[69] The study took place in Tuskegee, Alabama, and was supported by the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) in partnership with the Tuskegee Institute.[70] The study began in 1932, when syphilis was a widespread problem and there was no safe and effective treatment.[71] The study was designed to measure the progression of untreated syphilis. By 1947, penicillin had been shown to be an effective cure for early syphilis and was becoming widely used to treat the disease.[70] Its use in later syphilis, however, was still unclear.[71] Study directors continued the study and did not offer the participants treatment with penicillin.[70] This is debated, and some have found that penicillin was given to many of the subjects.[71]

In the 1960s, Peter Buxtun sent a letter to the CDC, who controlled the study, expressing concern about the ethics of letting hundreds of black men die of a disease that could be cured. The CDC asserted that it needed to continue the study until all of the men had died. In 1972, Buxtun went to the mainstream press, causing a public outcry. As a result, the program was terminated, a lawsuit brought those affected nine million dollars, and Congress created a commission empowered to write regulations to deter such abuses from occurring in the future.[70]

On 16 May 1997, thanks to the efforts of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee formed in 1994, survivors of the study were invited to the White House to be present when President Bill Clinton apologized on behalf of the United States government for the study.[72]

Syphilis experiments were also carried out in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948. They were United States-sponsored human experiments, conducted during the government of Juan José Arévalo with the cooperation of some Guatemalan health ministries and officials. Doctors infected soldiers, prisoners, and mental patients with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases, without the informed consent of the subjects, and then treated them with antibiotics. In October 2010, the U.S. formally apologized to Guatemala for conducting these experiments.[73]

List of cases

Elimination

In 2015, Cuba became the first country in the world to receive validation from WHO for eliminating mother to child transmission of syphilis.[74]

References

- Farhi, D; Dupin, N (Sep–Oct 2010). "Origins of syphilis and management in the immunocompetent patient: facts and controversies". Clinics in Dermatology. 28 (5): 533–38. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.011. PMID 20797514.

- Franzen, C (December 2008). "Syphilis in composers and musicians – Mozart, Beethoven, Paganini, Schubert, Schumann, Smetana". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 27 (12): 1151–57. doi:10.1007/s10096-008-0571-x. PMID 18592279. S2CID 947291.

- Kent ME, Romanelli F (February 2008). "Reexamining syphilis: an update on epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management". Ann Pharmacother. 42 (2): 226–36. doi:10.1345/aph.1K086. PMID 18212261. S2CID 23899851.

- Tampa, M; Sarbu, I; Matei, C; Benea, V; Georgescu, SR (15 March 2014). "Brief history of syphilis". Journal of Medicine and Life. 7 (1): 4–10. PMC 3956094. PMID 24653750.

- Maatouk I and Moutran R. History of syphilis: Between poetry and medicine. J Sex Med 2014;11:307–310.

- Rothschild, Bruce M.; Calderon, Fernando Luna; Coppa, Alfredo; Rothschild, Christine (October 2000). "First European Exposure to Syphilis: The Dominican Republic at the Time of Columbian Contact". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 31 (4): 936–41. doi:10.1086/318158. PMID 11049773.

- Maffie, James (2013). Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 1-45718-426-5. Olin and Xolotl

- Harper, Kristin N (2011). "The origin and antiquity of syphilis revisited: An Appraisal of Old World pre-Columbian evidence for treponemal infection". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 146 (S53): 99–133. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21613. PMID 22101689.

- ”Skeletons point to Columbus voyage for syphilis origins”; Science Daily

- Armelagos, George J.; Zuckerman, Molly K.; Harper, Kristin N. (March 2012). "The Science Behind Pre-Columbian Evidence of Syphilis in Europe: Research by Documentary". Evolutionary Anthropology. 21 (2): 50–57. doi:10.1002/evan.20340. PMC 3413456. PMID 22499439.

- Bollaert, WM (1864). "Introduction of Syphilis from the New World".

- http://www.sundaytimes.lk/101219/Timestwo/t2_01.html Pompeii skeletons reveal secrets of Roman family life

- Henneberg M, Henneberg RJ (1994). "Treponematosis in an Ancient Greek colony of Metaponto, Southern Italy 580–250 BCE". In O Dutour, G Palfi, J Berato, J-P Brun (eds.). The Origin of Syphilis in Europe, Before or After 1493?. Toulon-Paris: Centre Archeologique du Var, Editions Errance. pp. 92–98.

- Henneberg M, Henneberg RJ (2002). "Reconstructing Medical Knowledge in Ancient Pompeii from the Hard Evidence of Bones and Teeth". In J Renn, G Castagnetti (eds.). Homo Faber: Studies on Nature. Technology and Science at the Time of Pompeii. Rome: "L'Erma" di Bretschneider. pp. 169–87.

- Lobdell J, Owsley D (August 1974). "The origin of syphilis". Journal of Sex Research. 10 (1): 76–79. doi:10.1080/00224497409550828. S2CID 143393896. (via JSTOR)

- Gaul J.S., Grossschmidt K., Gusenbauer C., Kanz F. (2015). "A probable case of congenital syphilis from pre-Columbian Austria". Anthropologischer Anzeiger. 72 (4): 451–72. doi:10.1127/anthranz/2015/0504. PMID 26482430.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hartley, Charlotte (13 August 2020). "Medieval DNA suggests Columbus didn't trigger syphilis epidemic in Europe". Science. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2003). The Columbian exchange: biological and cultural consequences of 1492. New York: Praeger. p. 146. ISBN 0-275-98092-8.

- Debora MacKenzie (15 January 2008). "Columbus blamed for spread of syphilis". New Scientist.

- Harper, KN; Ocampo, PS; Steiner, BM; George, RW; Silverman, MS; Bolotin, S; Pillay, A; Saunders, NJ; Armelagos, GJ (January 2008). Ko, Albert (ed.). "On the Origin of the Treponematoses: A Phylogenetic Approach". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (1): e148. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000148. PMC 2217670. PMID 18235852. Lay summary – New Scientist (15 January 2008).

Some researchers have argued that the syphilis-causing bacterium, or its progenitor, was brought from the New World to Europe by Christopher Columbus and his men, while others maintain that the treponematoses, including syphilis, have a much longer history on the European continent.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-url=(help) - Mulligan CJ, Norris SJ, Lukehart SA (2008). "Molecular studies in Treponema pallidum evolution: toward clarity?". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (1): e184. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000184. PMC 2270795. PMID 18357339.

- Rumbaut, Ruben D. (1997). "The Great Pox: The French Disease in Renaissance Europe". JAMA. 278 (5): 440. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550050104045. ISSN 0098-7484.

- Diamond, Jared (1997). Guns, Germs and Steel. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 210. ISBN 84-8306-667-X.

- John Noble Wilford (15 January 2008). "Genetic Study Bolsters Columbus Link to Syphilis". The New York Times.

- "Columbus May Have Brought Syphilis to Europe", LiveScience

- "Pox and Paranoia in Renaissance Europe". History Today.

- Szreter, Simon; Siena, Kevin (2020). "The pox in Boswell's London: an estimate of the extent of syphilis infection in the metropolis in the 1770s†". The Economic History Review. 74 (2): 372–399. doi:10.1111/ehr.13000. ISSN 1468-0289.

- Fracastor, Hieronymus (1911). Syphilis. The Philmar Company.

- "Syphilis". Online Etymology Dictionary. 2001.

- Cassar, Charles (2002). "Concepts of Health and Illness in Early Modern Malta". Quaderns de l'Institut Català d'Antropologia. University of Malta (17–18): 55. ISSN 2385-4472. Archived from the original on 25 July 2017.

- "Syphilis, 1494–1923". Harvard University Open Library.

- Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- Semple, David; Smythe, Robert (2009). Oxford handbook of psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-19-923946-7.

- Tasioulas, Jacqueline (2010). The Makars. Edinburgh: Canongate. p. 302.

- Rudy's List of Archaic Medical Terms (2007-04-27). "B". Antiquus Morbus. Archived from the original on 2018-08-25. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

Referencing: Robley Dunglison (1874). Dunglison's Medical Dictionary – A Dictionary of Medical Science. Philadelphia: Collins. - Parascandola, John (2009). "From Mercury to Miracle Drugs: Syphilis Therapy over the Centuries". Pharmacy in History. 51 (1).

- Ozuah, Philip O. (March 2000). "Mercury poisoning". Current Problems in Pediatrics. 30 (3): 91–99 [91]. doi:10.1067/mps.2000.104054. PMID 10742922..

- Sir Henry Morris (1926). Summary of the Debate by the President (Speech). The Royal Society of Medicine.

- Tampa, Mircea (2014). "Brief History of Syphilis". Journal of Medicine and Life. 7 (1): 4–10. PMC 3956094. PMID 24653750.

- Grimes, MD, Jill; Fagerberg, MD, Krystyn; Smith, MD, Lori, eds. (2014). Sexually Transmitted Disease: An Encyclopedia of Diseases, Prevention, Treatment, and Issues. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. p. 583. ISBN 978-1-4408-0134-1.

- "Infectious Diseases at the Edward Worth Library: Treatment of Syphilis in Early Modern Europe". infectiousdiseases.edwardworthlibrary.ie. Edward Worth Library. 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-05-05. Retrieved 2015-12-19.

- Walker, TJ (December 1869). "The Treatment of Syphilis by the Hypodermic Injection of the Salts of Mercury". British Medical Journal. 2 (466): 605–08. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.466.605. PMC 2261112. PMID 20745696.

- Membrives, Eva Parra; Peinado, Miguel Ángel García (2012). Aspects of Literary Translation: Building Linguistic and Cultural Bridge in Past and Present. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 55. ISBN 978-3823367086.

- Dangler, Jean (2001). Mediating Fictions: Literature, Women Healers, and the Go-Between in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press. pp. 128–29. ISBN 0-8387-5452-X.

- Stein, Claudia (2009). Negotiating the French Pox in Early Modern Germany (English ed.). Farnham (Surrey, United Kingdom): Ashgate Publishing. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-7546-6008-8.

- Lach, Donald F. (February 1994). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume II. University of Chicago Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0226467306. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- Culpeper, Nicholas (1653). Culpeper's Complete Herbal (1816 ed.). London: Richard Evans. p. 84.

A strong decoction of the herbs and flowers...is an excellent cure for the French pox[.]

- Bynum, W. F. (1994). Science and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0521251099.

- Raju T (2006). "Hot brains: manipulating body heat to save the brain" (PDF). Pediatrics. 117 (2): e320–21. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1934. PMID 16452338. S2CID 21411790.

- Spink, W.W. "Infectious diseases: prevention and treatment in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries" U of Minnesota Press, 1978, p. 316.

- Brown, Kevin (2006). The Pox: The Life and Near Death of a Very Social Disease. Stroud: WSutton. pp. 85–111, 185–91.

- Grimes (ed.), p. 317.

- "Noguchi, Hideyo". The Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth ed.). Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

- Cabinet Office, Japan: Noguchi Prize

- Szreter, Simon; Siena, Kevin (2021). "The pox in Boswell's London: an estimate of the extent of syphilis infection in the metropolis in the 1770s†". The Economic History Review. 74 (2): 372–399. doi:10.1111/ehr.13000. ISSN 1468-0289. S2CID 225618214. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- "One in five Londoners had syphilis by age 35 in the late 18th century, historians estimate". MinnPost. 8 July 2020.

- Szreter, S. (25 February 2014). "The Prevalence of Syphilis in England and Wales on the Eve of the Great War: Re-visiting the Estimates of the Royal Commission on Venereal Diseases 1913-1916". Social History of Medicine. 27 (3): 508–529. doi:10.1093/shm/hkt123. ISSN 0951-631X. PMC 4109696. PMID 25067890. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- Green, T.; Talbot, M. D.; Morton, R. S. (1 June 2001). "The control of syphilis, a contemporary problem: a historical perspective". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 77 (3): 214–217. doi:10.1136/sti.77.3.214. ISSN 1368-4973. PMC 1744312. PMID 11402234. S2CID 11160963. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- Laird, S. M. (1 March 1959). "Elimination of Congenital Syphilis". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 35 (1): 15–19. doi:10.1136/sti.35.1.15. ISSN 1368-4973. PMC 1047229. PMID 13651659. S2CID 30231405. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- Willeford, Wesley G.; Bachmann, Laura H. (26 September 2016). "Syphilis ascendant: a brief history and modern trends". Tropical Diseases, Travel Medicine and Vaccines. 2: 20. doi:10.1186/s40794-016-0039-4. ISSN 2055-0936. PMC 5530970. PMID 28883964.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Summer 2007, pp. 55–56.

- Eisler, CT (Winter 2009). "Who is Dürer's "Syphilitic Man"?". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 52 (1): 48–60. doi:10.1353/pbm.0.0065. PMID 19168944. S2CID 207268142.

- Hughes, Robert (2007). Things I didn't know : a memoir (1st Vintage Book ed.). New York: Vintage. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-307-38598-7.

- Wilson, [ed]: Joanne Entwistle, Elizabeth (2005). Body dressing ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Oxford: Berg Publishers. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-85973-444-5.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Frith, John (2012). "Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on its Origin". Journal of Military and Veterans' Health. 20 (4).

- Tampa, Mircea; et al. (2014). "Brief History of Syphilis". Journal of Medicine and Life. 7 (1): 4–10. PMC 3956094. PMID 24653750.

- Reid, Basil A. (2009). Myths and realities of Caribbean history ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8173-5534-0.

- "Preparation and Use of Guayaco for Treating Syphilis". Jan van der Straet. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- Katz RV, Kegeles SS, Kressin NR, et al. (November 2006). "The Tuskegee Legacy Project: Willingness of Minorities to Participate in Biomedical Research". J Health Care Poor Underserved. 17 (4): 698–715. doi:10.1353/hpu.2006.0126. PMC 1780164. PMID 17242525.

- "U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- White, RM (13 March 2000). "Unraveling the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 160 (5): 585–98. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.5.585. PMID 10724044.

- "Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: President Bill Clinton's Apology". University of Virginia Health Sciences Library. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- "U.S. apologizes for newly revealed syphilis experiments done in Guatemala". The Washington Post. 1 October 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

The United States revealed on Friday that the government conducted medical experiments in the 1940s in which doctors infected soldiers, prisoners and mental patients in Guatemala with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases.

- "WHO validates elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis in Cuba". WHO. 30 June 2015. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

External links

- The V.D. Radio Project at The WNYC Archives, a collection of recordings from a 1949 public health campaign created by the United States Public Health Service in collaboration with Columbia University.